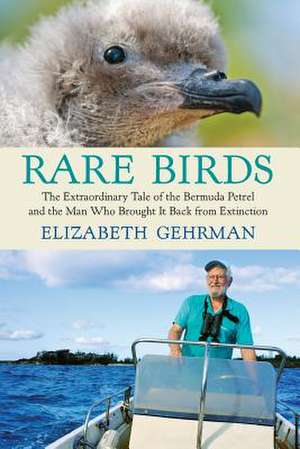

Rare Birds: The Extraordinary Tale of the Bermuda Petrel and the Man Who Brought It Back from Extinction

Autor Elizabeth Gehrmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 iul 2015

Rare Birds is a tale of obsession, of hope, of fighting for redemption against incredible odds. It is the story of how Bermuda’s David Wingate changed the world—or at least a little slice of it—despite the many voices telling him he was crazy to try.

This tiny island in the middle of the North Atlantic was once the breeding ground for millions of Bermuda petrels. Also known as cahows, the graceful and acrobatic birds fly almost nonstop most of their lives, drinking seawater and sleeping on the wing. But shortly after humans arrived here, more than three centuries ago, the cahows had vanished, eaten into extinction by the country’s first settlers.

Then, in the early 1900s, tantalizing hints of the cahows’ continued existence began to emerge. In 1951, an American ornithologist and a Bermudian naturalist mounted a last-ditch effort to find the birds that had come to seem little more than a legend, bringing a teenage Wingate—already a noted birder—along for the ride. When the stunned scientists pulled a blinking, docile cahow from deep within a rocky cliffside, it made headlines around the world—and told Wingate what he was put on this earth to do.

Starting with just seven nesting pairs of the birds, Wingate would devote his life to giving the cahows the chance they needed in their centuries-long struggle for survival — battling hurricanes, invasive species, DDT, the American military, and personal tragedy along the way.

It took six decades of obsessive dedication, but the cahow, still among the rarest of seabirds, has reached the hundred-pair mark and continues its nail-biting climb to repopulation. And Wingate has seen his dream fulfilled as the birds returned to Nonsuch, an island habitat he hand-restored for them plant-by-plant in anticipation of this day. His passion for resuscitating this “Lazarus species” has made him an icon among birders, and his story is an inspiring celebration of the resilience of nature, the power of persistence, and the value of going your own way.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 163.14 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 245

Preț estimativ în valută:

31.22€ • 32.68$ • 25.83£

31.22€ • 32.68$ • 25.83£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 05-19 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807010785

ISBN-10: 0807010782

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807010782

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Recenzii

“There's nothing more exciting than a comeback story, and this is one for the ages. You will quickly find yourself rooting for cahows, or Bermuda petrels, a bird you likely didn't even know existed before opening these pages. And you'll be swept along by Elizabeth Gehrman’s clean, racing prose as you learn about the threats the petrels face--including Snowy owls, DDT and the American military--as the species fights its way back to life. Finally, you'll meet the rarest bird of all, David Wingate, the gentle, stubborn, charming quixotic bird-man, who has staked his whole life on playing midwife to the bird's return.”

— David Gessner, author of Return of the Osprey

“Read Elizabeth’s book if you care about nature and despair whether man can harmonize with it. Read Rare Birds if you need a human hero, for David Wingate surely is one, and love animals, for you will surely love his Bermuda petrels. Read this extraordinary tale of a seemingly-extinct breed of bird and the man who rescued it if you are heading to Bermuda, or anywhere, and want to bring a book you will relish, remember, and want to give as a gift.”—Larry Tye, author of Superman and Satchel

“There are few success stories in the efforts to stop the relentless assault on the species we share the planet with, and Rare Birds is a lovely chronicle of one of them. The story of Wingate’s heroic efforts to bring the docile cahow back from the brink of extinction is unassumingly but beautifully told, and chockfull of fascinating natural history. It captures the particular fragility and intensity of the life on islands, including that of the protagonist himself.”—Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair contributing editor

"Vanishing species these days are a dime a dozen. The truly rarer bird is the human being whose life stands between a creature and its permanent oblivion. David Wingate is a truly pivotal person on whom the fate of a whole species turned. It's a remarkable seabird whose existence depended on this rare man. And this book, rendered with style and grace, is his story." —Carl Safina, author of Song for the Blue Ocean and The View From Lazy Point; A Natural Year in an Unnatural World

“Gerhman’s detailed account of Wingate’s life demonstrates what amazing feats can be accomplished given sufficient time and determination. Environmentalists and bird lovers alike will enjoy this look at the restoration of an endangered bird.”—Kirkus

“Wingate’s single-minded passion and his ability to foster the birds, habitat, and Bermudans’ environmental awareness should make readers wish for more ‘rare birds.’” —Publishers Weekly

“The fascinating tale of one man's fight to save the cahow, a bird believed extinct since the early 1600s.’” —Kirkus Reviews

From the Hardcover edition.

— David Gessner, author of Return of the Osprey

“Read Elizabeth’s book if you care about nature and despair whether man can harmonize with it. Read Rare Birds if you need a human hero, for David Wingate surely is one, and love animals, for you will surely love his Bermuda petrels. Read this extraordinary tale of a seemingly-extinct breed of bird and the man who rescued it if you are heading to Bermuda, or anywhere, and want to bring a book you will relish, remember, and want to give as a gift.”—Larry Tye, author of Superman and Satchel

“There are few success stories in the efforts to stop the relentless assault on the species we share the planet with, and Rare Birds is a lovely chronicle of one of them. The story of Wingate’s heroic efforts to bring the docile cahow back from the brink of extinction is unassumingly but beautifully told, and chockfull of fascinating natural history. It captures the particular fragility and intensity of the life on islands, including that of the protagonist himself.”—Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair contributing editor

"Vanishing species these days are a dime a dozen. The truly rarer bird is the human being whose life stands between a creature and its permanent oblivion. David Wingate is a truly pivotal person on whom the fate of a whole species turned. It's a remarkable seabird whose existence depended on this rare man. And this book, rendered with style and grace, is his story." —Carl Safina, author of Song for the Blue Ocean and The View From Lazy Point; A Natural Year in an Unnatural World

“Gerhman’s detailed account of Wingate’s life demonstrates what amazing feats can be accomplished given sufficient time and determination. Environmentalists and bird lovers alike will enjoy this look at the restoration of an endangered bird.”—Kirkus

“Wingate’s single-minded passion and his ability to foster the birds, habitat, and Bermudans’ environmental awareness should make readers wish for more ‘rare birds.’” —Publishers Weekly

“The fascinating tale of one man's fight to save the cahow, a bird believed extinct since the early 1600s.’” —Kirkus Reviews

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

Prologue

Chapter One: The Bird Man of Bermuda

Chapter Two: The Spoyle and Havock of the Cahowes

Chapter Three: Seeking the Invisible

Chapter Four: Unraveling the Mysteries

Chapter Five: Building a New, Old World

Chapter Six: A Discouraging Decade

Chapter Seven: Coming of Age

Chapter Eight: A Habitat Takes Shape

Chapter Nine: Leaving the Nest

Chapter Ten: Loose Ends and Ill Winds

Chapter Eleven: Moving On, Coming Home

Acknowledgments

References

Index

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Gehrman is a frequent contributor to the Boston Globe Magazine and has written for the New York Times, Archaeology, More, and This Old House. She lives in Boston and upstate New York.

Extras

From Chapter 1

David Wingate wants to see his birds. “This is cahow weather,” he says, peering through the rain-splashed windshield of his white Suzuki Alto at treetops dancing violently in the wind. “We may be miserable, but the cahows are just yippee-happy right now. If we could go out to Nonsuch tonight, they’d be celebrating.”

Just a handful of people have seen cahows in flight, and even fewer have witnessed the staggeringly graceful, scramjet-fast aerial court- ship they perform on only the darkest fall and winter nights. Wingate, though, has spent enough time with the birds that he has felt their wings brush the top of his head as they darted past him in the black- ened sky, gliding ever slower through the air before dropping to land like a cartoon anvil. But in the past few years things have changed, and troubles from bad knees to bad blood have conspired to keep him from the birds he calls his first love.

This week he’s supposed to make his first trip to Nonsuch at night in two years. He’d been trying to get out there—or at least into the harbor in his boat—for a night watch once or twice every November since he moved off the island in 2003, but last year he didn’t go because of the knee-replacement surgery that laid him up for six months and left six-inch vertical scars in the dead center of both his legs. Before that—well, it’s a long story.

Mid-November is when the birds are most active, from a human perspective. It’s when the returning fledglings arrive at Castle Harbour after as much as four years spent flying virtually nonstop, drinking seawater and sleeping on the wing. During that time a young cahow might travel thousands of miles a week, weaving in and out among the rolling waves and heaving swells of the open ocean, alone feathered missile gliding and banking along the westerlies as it roams over millions of square miles of the Atlantic. Then, one day, a day like every other in the bird’s life so far, some unknowable instinct kicks in; some primal urge tells it to head back to Bermuda to find a mate. And, like a high school senior hustling to Cancun for spring break, it does. And when it arrives, it lands within three yards of the tree or rock or sheer cliff wall from which it fledged. When it takes off again to get to the business at hand, it rises and dips through the night sky and calls to its new friends in low, spectral moans until that special someone answers and the sexual chemistry becomes so achingly clear that the other birds must roll their eyes and tell the pair to get a burrow.

Seeing that, to Wingate, is heaven, an adrenaline high like no other. But this week, as in Novembers recently past, the Fates are refusing to allow him his greatest thrill.

First, there’s the weather, which is often unsettled in Bermuda this time of year. What the weather service describes as a “solid cloud deck” is hovering over the country; tomorrow it will combine with a low- pressure system from the south and the next day with the nor’easter created by what’s left of Hurricane Ida as it charges up the coast of the United States, generating a mini perfect storm that will result in near-constant rain, winds gusting to 33 miles an hour, and a total of just a few hours of sunshine over the next three days. The small-craft warning that will be issued for each of those days would most certainly apply to Wingate’s battered 17-foot Boston Whaler—not that that sort of thing usually keeps him out of the water.

Far worse than the weather, for Wingate, is that he threw his back out yesterday after having to bail his boat with a hand pump because the electrical system’s on the fritz again. (Covering the boat while it’s moored, he says, is “too much trouble.”)

He turns into the parking lot of a bungalow-style pink building called Shorelands, which houses the Bermuda Department of Conservation Services, and slowly begins to extricate himself from his sardine can of a car, the smallest he could find in the country. He’s here to go through two plastic storage containers full of old photographs to select some for a Canadian filmmaker who’s in town shooting the cahows for a DVD series on the environment. But Wingate can’t carry the bins. He can barely make it into the building. He hobbles up the sloping lawn and, once inside, leans on any available surface as he plods forward, wincing and groaning all the way.

“I’ve turned overnight into a doddering old man,” he says, finally lowering himself into an office chair in a first-floor conference room, where he can spread out the pictures on an enormous laminated table. “This is not me, you’ll see.”

At seventy-five, Wingate is a trim six feet tall and broad-shouldered, with a full head of uncombed white hair, thin lips, watery blue eyes, and the slightly crooked teeth of a British schoolboy. He has a short beard, also white, and his dress is emphatically casual, tending to- ward shorts, polo shirts, and boat shoes or Crocs for all but the most formal occasions.

“Whenever Dad had to come to something at school,” his daughter Karen Wingate remembers, “my sister and I would be in agony. We knew he’d be late. And if he comes, what will he be wearing? Ripped shorts and a shirt covered in bird poop? He was always scruffy, with his hands bleeding and burrs clinging to him, because he’d be off in the bushes after a bird.”

Like most Bermudians, Wingate speaks with a mix of accents—in his case, Scottish, handed down from his father’s side, and English, from his mother’s. Thus his nasally cannot becomes canna and glasses something like glahshees. Though most people pronounce the bird’s name ka-HOW, as in “How now brown cahow,” Wingate more often says KA-how, rhyming the first syllable with the vowel sound in the American pronunciation of laugh.

He had a skin-cancer scare last summer when he developed a per- sistent sore on his lip. Though a biopsy proved negative, just to be on the safe side he cut out a rectangular piece of cardboard and affixed it, dangling, to the back of his baseball cap with blue painter’s tape. On cloudless days, he works the thing down over the bill of the hat, past his wire-framed aviator-style bifocals, and over his mouth, where it jumps slightly whenever he talks. When asked why he doesn’t just use zinc oxide on his lips, he replies that he prefers a mechanical barrier. He’s thinking about replacing the cardboard soon with a leather version, maybe in the shape of a handlebar mustache—“to look like Mark Twain,” he says with a chuckle.

“I think everyone, even his best friends, would say he’s, well, he’s not certifiable, but he’s certainly a genuine eccentric,” David Saul says of Wingate. Saul, a former finance minister, former premier, bird lover, and raconteur, is no slouch himself in the eccentricity department, with a specially made steel coffin—guillotine-ended for easy opening—accumulating coral while it waits for him at the bottom of Devonshire Bay a quarter-mile from the backyard of his house.

Saul can’t recall any particular anecdotes to back up this assertion.

“No, nothing that I—I wouldn’t have even mentally recorded any- thing like that because everything about him was strange. You’d meet him and there’d be a bird in his pocket. You know, what could be unusual about that?”

A live bird?

“Oh, sure! To open up his car and—I am sure when he was conservation officer he carried birds, turtles, live and dead, many, many dead, scores, if not hundreds, dead, in his various vehicles. But this would not be considered to be, you know, you wouldn’t go home and say, ‘I just saw David Wingate, guess what!’ Well, they’d say—” He shrugs. “If he was acting normal, we’d think he was ill.”

Wingate was nicknamed Bird in grammar school, partly, he speculates, because of his prominent hooked nose. Saul dismisses this idea. “No, they’d’ve called him Hawky,” he says. “It was because of his inter- est in birds, to the exclusion of everything else, probably even girls, at the time. Everyone in Bermuda who’s over fifty still addresses him as Bird Wingate.”

Saul, who is several years younger than Wingate and knew him only by reputation when they were growing up, maintains that Win- gate took his childhood nickname as a badge of honor, but Wingate recalls it very differently. At a time in life when fitting in is the most essential tool of social success, he was openly different, and he re- members being teased and bullied for his unusual hobby. “I was very lonely,” Wingate says of those days.“In fact, I had a bit of an inferiority complex.”

Wingate may have felt he was being cruelly taunted by the other boys at the Saltus Grammar School, but he also admits he “disdained” the bullies for—ironically—their single-mindedness. The difference was that while they loved football and cricket, Wingate’s pursuit was, literally, loftier. He has kept detailed diaries since 1950, and in the first few books, he repeatedly mentions his disinclination for man- datory after-school sports, even going so far as to note that “every- thing turned out well” the day he was sent to detention because it got him out of “games.” In February of that year, two days after the first local newspaper article about him appeared in the Royal Gazette— “boy bird watcher has identified fifty different sPecies in year,” reads the front-page headline, in 36-point type—comes the following entry:

I was late for school, and found it a most miserable day, because the whole sixth form joked & laughed about my bird-watching as though it was a horrible crime.

By the next semester he seems to have toughened up a bit, as he mentions in passing “the perpetual annoyance and stupid name-calling such as ‘Birdy’ and ‘Bird-Brain.’”

Wandering around with a notebook and binoculars, meticulously recording his sightings, he must have seemed hopelessly nerdy to the more sportive boys. But despite the mutual antipathy, he may even then have been beginning to earn their grudging respect, for in a place as small as Bermuda, it doesn’t take long to make a name for your- self. By age fourteen, Wingate was presenting the neighbors with gifts of his ornithological lists and diaries and getting phone calls from adults all over the island—including at least one from someone at the Bermuda Biological Station—to come and identify unusual birds for them.

“If you ever had a sick bird,” Saul recalls, “an owl that struck the electric cables or anything, you just took it to his house and dumped it. Don’t even bother to ring, to knock the door. Just leave it there. And if it was dead, he would stuff it. I would imagine he stuffed half the birds at the aquarium museum. In the general population’s mind, the man is synonymous with birds. You just say, ‘You know that crazy birdman,’ and they’d all say, ‘You mean David Wingate?’ ‘Yes, David Wingate.’”

Just a few years ago, Wingate’s daughter Janet met a man with a cat who, without knowing who she was, volunteered that the cat’s name was Wingate because, the man said, “he looovvves de birds.”

Wingate wasn’t always obsessed with birds, but he was preoccupied with the natural world from the time he could walk. At age three, he collected a herd of wood lice that he called his beesh, for beasts. He kept them in a matchbox and took them to bed with him, until his mother found them crawling all over the pillow. Chastened not by her disapproval—his parents were tolerant of his diversions—but by the possibility that she might expel his pets from their new homes, he simply relocated his menageries, catching bugs of various sorts and stashing them under the bed instead of in it. Occasionally a spider would escape and build a web over him as he slept.

“When you’re a kid,” he says of his attraction to crawling things, “your nose is close to the ground.”

Wingate’s parents, a postal employee and a legal secretary, didn’t seem to know where their “born naturalist” came from, but were will- ing to indulge him, particularly as he was the baby of the family for thirteen years, until his sister Katharine came along. After a brief flirtation with astronomy—abandoned when, as he wrote in 1950, “I could not get the same thrill as I did before I found myself mak- ing silly blunders in judging the stars”—at age eleven his interest in the natural world took a turn toward birds. His older brother, Peter, had started an egg collection, which was a fairly standard pastime for Bermudian boys at the time, despite laws meant to protect nests from poaching.

“Every kid in the English countryside had a bird-egg collection,” Wingate says, “going way back to the 1700s. Interest peaked in the nineteenth century.”

David Wingate wants to see his birds. “This is cahow weather,” he says, peering through the rain-splashed windshield of his white Suzuki Alto at treetops dancing violently in the wind. “We may be miserable, but the cahows are just yippee-happy right now. If we could go out to Nonsuch tonight, they’d be celebrating.”

Just a handful of people have seen cahows in flight, and even fewer have witnessed the staggeringly graceful, scramjet-fast aerial court- ship they perform on only the darkest fall and winter nights. Wingate, though, has spent enough time with the birds that he has felt their wings brush the top of his head as they darted past him in the black- ened sky, gliding ever slower through the air before dropping to land like a cartoon anvil. But in the past few years things have changed, and troubles from bad knees to bad blood have conspired to keep him from the birds he calls his first love.

This week he’s supposed to make his first trip to Nonsuch at night in two years. He’d been trying to get out there—or at least into the harbor in his boat—for a night watch once or twice every November since he moved off the island in 2003, but last year he didn’t go because of the knee-replacement surgery that laid him up for six months and left six-inch vertical scars in the dead center of both his legs. Before that—well, it’s a long story.

Mid-November is when the birds are most active, from a human perspective. It’s when the returning fledglings arrive at Castle Harbour after as much as four years spent flying virtually nonstop, drinking seawater and sleeping on the wing. During that time a young cahow might travel thousands of miles a week, weaving in and out among the rolling waves and heaving swells of the open ocean, alone feathered missile gliding and banking along the westerlies as it roams over millions of square miles of the Atlantic. Then, one day, a day like every other in the bird’s life so far, some unknowable instinct kicks in; some primal urge tells it to head back to Bermuda to find a mate. And, like a high school senior hustling to Cancun for spring break, it does. And when it arrives, it lands within three yards of the tree or rock or sheer cliff wall from which it fledged. When it takes off again to get to the business at hand, it rises and dips through the night sky and calls to its new friends in low, spectral moans until that special someone answers and the sexual chemistry becomes so achingly clear that the other birds must roll their eyes and tell the pair to get a burrow.

Seeing that, to Wingate, is heaven, an adrenaline high like no other. But this week, as in Novembers recently past, the Fates are refusing to allow him his greatest thrill.

First, there’s the weather, which is often unsettled in Bermuda this time of year. What the weather service describes as a “solid cloud deck” is hovering over the country; tomorrow it will combine with a low- pressure system from the south and the next day with the nor’easter created by what’s left of Hurricane Ida as it charges up the coast of the United States, generating a mini perfect storm that will result in near-constant rain, winds gusting to 33 miles an hour, and a total of just a few hours of sunshine over the next three days. The small-craft warning that will be issued for each of those days would most certainly apply to Wingate’s battered 17-foot Boston Whaler—not that that sort of thing usually keeps him out of the water.

Far worse than the weather, for Wingate, is that he threw his back out yesterday after having to bail his boat with a hand pump because the electrical system’s on the fritz again. (Covering the boat while it’s moored, he says, is “too much trouble.”)

He turns into the parking lot of a bungalow-style pink building called Shorelands, which houses the Bermuda Department of Conservation Services, and slowly begins to extricate himself from his sardine can of a car, the smallest he could find in the country. He’s here to go through two plastic storage containers full of old photographs to select some for a Canadian filmmaker who’s in town shooting the cahows for a DVD series on the environment. But Wingate can’t carry the bins. He can barely make it into the building. He hobbles up the sloping lawn and, once inside, leans on any available surface as he plods forward, wincing and groaning all the way.

“I’ve turned overnight into a doddering old man,” he says, finally lowering himself into an office chair in a first-floor conference room, where he can spread out the pictures on an enormous laminated table. “This is not me, you’ll see.”

At seventy-five, Wingate is a trim six feet tall and broad-shouldered, with a full head of uncombed white hair, thin lips, watery blue eyes, and the slightly crooked teeth of a British schoolboy. He has a short beard, also white, and his dress is emphatically casual, tending to- ward shorts, polo shirts, and boat shoes or Crocs for all but the most formal occasions.

“Whenever Dad had to come to something at school,” his daughter Karen Wingate remembers, “my sister and I would be in agony. We knew he’d be late. And if he comes, what will he be wearing? Ripped shorts and a shirt covered in bird poop? He was always scruffy, with his hands bleeding and burrs clinging to him, because he’d be off in the bushes after a bird.”

Like most Bermudians, Wingate speaks with a mix of accents—in his case, Scottish, handed down from his father’s side, and English, from his mother’s. Thus his nasally cannot becomes canna and glasses something like glahshees. Though most people pronounce the bird’s name ka-HOW, as in “How now brown cahow,” Wingate more often says KA-how, rhyming the first syllable with the vowel sound in the American pronunciation of laugh.

He had a skin-cancer scare last summer when he developed a per- sistent sore on his lip. Though a biopsy proved negative, just to be on the safe side he cut out a rectangular piece of cardboard and affixed it, dangling, to the back of his baseball cap with blue painter’s tape. On cloudless days, he works the thing down over the bill of the hat, past his wire-framed aviator-style bifocals, and over his mouth, where it jumps slightly whenever he talks. When asked why he doesn’t just use zinc oxide on his lips, he replies that he prefers a mechanical barrier. He’s thinking about replacing the cardboard soon with a leather version, maybe in the shape of a handlebar mustache—“to look like Mark Twain,” he says with a chuckle.

“I think everyone, even his best friends, would say he’s, well, he’s not certifiable, but he’s certainly a genuine eccentric,” David Saul says of Wingate. Saul, a former finance minister, former premier, bird lover, and raconteur, is no slouch himself in the eccentricity department, with a specially made steel coffin—guillotine-ended for easy opening—accumulating coral while it waits for him at the bottom of Devonshire Bay a quarter-mile from the backyard of his house.

Saul can’t recall any particular anecdotes to back up this assertion.

“No, nothing that I—I wouldn’t have even mentally recorded any- thing like that because everything about him was strange. You’d meet him and there’d be a bird in his pocket. You know, what could be unusual about that?”

A live bird?

“Oh, sure! To open up his car and—I am sure when he was conservation officer he carried birds, turtles, live and dead, many, many dead, scores, if not hundreds, dead, in his various vehicles. But this would not be considered to be, you know, you wouldn’t go home and say, ‘I just saw David Wingate, guess what!’ Well, they’d say—” He shrugs. “If he was acting normal, we’d think he was ill.”

Wingate was nicknamed Bird in grammar school, partly, he speculates, because of his prominent hooked nose. Saul dismisses this idea. “No, they’d’ve called him Hawky,” he says. “It was because of his inter- est in birds, to the exclusion of everything else, probably even girls, at the time. Everyone in Bermuda who’s over fifty still addresses him as Bird Wingate.”

Saul, who is several years younger than Wingate and knew him only by reputation when they were growing up, maintains that Win- gate took his childhood nickname as a badge of honor, but Wingate recalls it very differently. At a time in life when fitting in is the most essential tool of social success, he was openly different, and he re- members being teased and bullied for his unusual hobby. “I was very lonely,” Wingate says of those days.“In fact, I had a bit of an inferiority complex.”

Wingate may have felt he was being cruelly taunted by the other boys at the Saltus Grammar School, but he also admits he “disdained” the bullies for—ironically—their single-mindedness. The difference was that while they loved football and cricket, Wingate’s pursuit was, literally, loftier. He has kept detailed diaries since 1950, and in the first few books, he repeatedly mentions his disinclination for man- datory after-school sports, even going so far as to note that “every- thing turned out well” the day he was sent to detention because it got him out of “games.” In February of that year, two days after the first local newspaper article about him appeared in the Royal Gazette— “boy bird watcher has identified fifty different sPecies in year,” reads the front-page headline, in 36-point type—comes the following entry:

I was late for school, and found it a most miserable day, because the whole sixth form joked & laughed about my bird-watching as though it was a horrible crime.

By the next semester he seems to have toughened up a bit, as he mentions in passing “the perpetual annoyance and stupid name-calling such as ‘Birdy’ and ‘Bird-Brain.’”

Wandering around with a notebook and binoculars, meticulously recording his sightings, he must have seemed hopelessly nerdy to the more sportive boys. But despite the mutual antipathy, he may even then have been beginning to earn their grudging respect, for in a place as small as Bermuda, it doesn’t take long to make a name for your- self. By age fourteen, Wingate was presenting the neighbors with gifts of his ornithological lists and diaries and getting phone calls from adults all over the island—including at least one from someone at the Bermuda Biological Station—to come and identify unusual birds for them.

“If you ever had a sick bird,” Saul recalls, “an owl that struck the electric cables or anything, you just took it to his house and dumped it. Don’t even bother to ring, to knock the door. Just leave it there. And if it was dead, he would stuff it. I would imagine he stuffed half the birds at the aquarium museum. In the general population’s mind, the man is synonymous with birds. You just say, ‘You know that crazy birdman,’ and they’d all say, ‘You mean David Wingate?’ ‘Yes, David Wingate.’”

Just a few years ago, Wingate’s daughter Janet met a man with a cat who, without knowing who she was, volunteered that the cat’s name was Wingate because, the man said, “he looovvves de birds.”

Wingate wasn’t always obsessed with birds, but he was preoccupied with the natural world from the time he could walk. At age three, he collected a herd of wood lice that he called his beesh, for beasts. He kept them in a matchbox and took them to bed with him, until his mother found them crawling all over the pillow. Chastened not by her disapproval—his parents were tolerant of his diversions—but by the possibility that she might expel his pets from their new homes, he simply relocated his menageries, catching bugs of various sorts and stashing them under the bed instead of in it. Occasionally a spider would escape and build a web over him as he slept.

“When you’re a kid,” he says of his attraction to crawling things, “your nose is close to the ground.”

Wingate’s parents, a postal employee and a legal secretary, didn’t seem to know where their “born naturalist” came from, but were will- ing to indulge him, particularly as he was the baby of the family for thirteen years, until his sister Katharine came along. After a brief flirtation with astronomy—abandoned when, as he wrote in 1950, “I could not get the same thrill as I did before I found myself mak- ing silly blunders in judging the stars”—at age eleven his interest in the natural world took a turn toward birds. His older brother, Peter, had started an egg collection, which was a fairly standard pastime for Bermudian boys at the time, despite laws meant to protect nests from poaching.

“Every kid in the English countryside had a bird-egg collection,” Wingate says, “going way back to the 1700s. Interest peaked in the nineteenth century.”