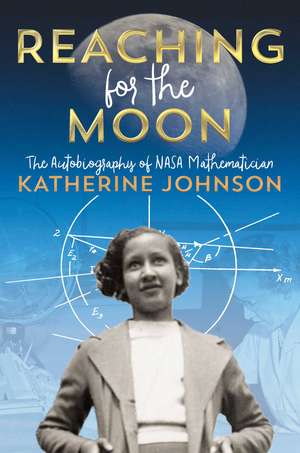

Reaching for the Moon: The Autobiography of NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson

Autor Katherine Johnsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – oct 2020 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Inspiring autobiography of NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson, who helped launch Apollo 11.

As a young girl, Katherine Johnson showed an exceptional aptitude for math. In school she quickly skipped ahead several grades and was soon studying complex equations with the support of a professor who saw great promise in her. But ability and opportunity did not always go hand in hand. As an African American and a girl growing up in an era of brutal racism and sexism, Katherine faced daily challenges. Still, she lived her life with her father’s words in mind: “You are no better than anyone else, and nobody else is better than you.”

In the early 1950s, Katherine was thrilled to join the organization that would become NASA. She worked on many of NASA’s biggest projects including the Apollo 11 mission that landed the first men on the moon.

Katherine Johnson’s story was made famous in the bestselling book and Oscar-nominated film Hidden Figures. Now in Reaching for the Moon she tells her own story for the first time, in a lively autobiography that will inspire young readers everywhere.

Preț: 45.50 lei

Preț vechi: 56.95 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 68

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.71€ • 9.16$ • 7.19£

8.71€ • 9.16$ • 7.19£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-09 aprilie

Livrare express 12-18 martie pentru 28.90 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534440845

ISBN-10: 1534440844

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: foil stamp), matte lam; digital

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534440844

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: foil stamp), matte lam; digital

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Katherine Johnson (1918–2020) was a former NASA mathematician whose work was critical to the success of many of their initiatives, including the Apollo program and the start of the Space Shuttle program. Throughout her long career she received numerous awards, including the nation’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from President Barack Obama.

Extras

Reaching for the Moon

![]()

It’s not every day you wake up with a mission on your mind, but I had a mission and I was determined to accomplish it. Except for the sound of Mama humming and the clinking of dishes as she washed them in the sink, the house was quiet. Moments earlier Daddy had left for work and my brothers and sister had set off to school. As I sat at the kitchen table still fiddling with my oatmeal, I couldn’t get my brother Charlie out of my mind. I kept revisiting the scene at the kitchen table the night before, when he’d struggled with his math homework.

First Mama had tried to assist him with it. Back before she’d had Horace, Margaret, Charlie, and me, she had been a teacher. She should have been able to help him figure out his schoolwork.

But the way he had slumped over onto one elbow had signaled that he was feeling frustrated.

“Sit up straight,” Mama had told him, and he did.

Horace and Margaret were steadily scribbling away at their assignments, apparently unbothered by Charlie’s challenges.

“Maybe you can explain it better than I can, Josh,” Mama said to Daddy, who was sitting in the front room reading the White Sulphur Sentinel, our town’s newspaper. Daddy loved to read the paper. He also read the almanac. Mama adored us, but she was very orderly and from time to time she could be a bit strict. Our father was a little more relaxed.

![]()

My parents, Joshua and Joylette Coleman.

Daddy set the paper down and slowly unfurled himself from his favorite chair. More than six feet tall, he towered above most everyone.

“Let’s see what we can do here, Son,” he said, sitting down and scooting closer to his youngest son, the chair scraping loudly across the oak floor.

Daddy put his left arm around Charlie, who leaned into him.

“I can’t figure it out,” Charlie said, his lack of confidence evident in his voice.

“Yes, you can,” Daddy told him. “We just have to explain it so that you get it. Once you understand the background of any idea, you can figure any problem out for yourself.”

Daddy’s personality could be more comforting than Mama’s. Numbers were also Daddy’s strength. He may have had only a sixth-grade education, but he was really good with figures. Envisioning things was one of his strong points. He was so good that he could look at an entire oak, pine, or even a chestnut tree, and tell you how many logs it would yield once it had been cut down. We even lived in a home he had built for us.

Charlie was two years older than me, but for some reason he seemed to be a little slow. At least, that’s what I thought back then. I would be well into adulthood before I discovered that the issue wasn’t that he was slow. The truth of the matter was that I was fast. It turned out that I was very gifted in math.

Math had always come easily to me. I loved numbers and numbers loved me. They followed me everywhere. No matter what I did, I was always finding something to count: the floorboards, the cracks in the sidewalk, the trees as I walked by, the train cars stacked with timber and those piled with coal that lumbered along the edge of our town each day. The number of times the train engineers blew the whistle as they traveled through the trees, echoing off the granite bedrock that rose above us and formed the valley within which our town, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, was nestled.

![]()

Me at age two with my brothers and sister.

That was just the way that my mind worked. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight forks. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight plates. One, two, three serving spoons. Mama was very well organized, but my mind took her sense of order one step further. I always knew how many of everything there were. Things were there and could be counted and accounted for, so that’s what I did.

So when Charlie found it hard to understand numbers, it really bothered me. And it disturbed me even more when he didn’t understand even after both Mama and Daddy had tried to teach them to him.

At that point I decided to take things into my own hands. And that was why, even though I was only four years old, I told my plan to Mama, then walked out the front door, then four steps across the porch, eight steps down the front stairs, and five steps down the front walk, and set off toward the school.

As I marched out of our front yard and turned onto the sidewalk, I waved at Mrs. Hopkins, who was sweeping the front porch of her family’s two-story house across our street. Church Street was the center of Colored life in White Sulphur Springs. Back then the same people we now call African American or Black were called Colored or Negro. (It’s important not to use those words to describe people today or you will certainly offend them.)

I strode slightly uphill past five houses and St. James United Methodist Church, where we worshipped, to the corner of Barton Road. That’s where Church Street ended, as what had been a slight rise suddenly became very steep—too steep to sled after the snow fell. It was covered with maple, sycamore, and pine trees, and during the spring and summer months, grass.

About one hundred yards up that hill ran the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway tracks, where black and navy-blue trains with a yellow Cheshire cat painted on them rumbled through town twice daily, morning and evening. The C&O trains carried coal, lumber, and supplies as well as people from the Virginia coast (which was about six hours southeast) northwestward through the Allegheny Mountains, part of the Appalachian mountain range of West Virginia and southern Ohio. The C&O then carried its load over the Ohio River, across that state on into Detroit and other parts of Michigan. Some trains traveled even farther westward into Indiana and on to the growing industrial cities of Gary, Indiana, and Chicago, Illinois.

A passenger train also rolled through town, carrying not only travelers of modest means but also the well-appointed private coaches that the wealthy magnates of that era owned and used to travel around the country.

I turned left onto Barton and followed it one block until I came to a dirt path on my right. About one hundred feet up that path sat the Mary McLeod Bethune Grade School, the white wooden two-room schoolhouse where our town’s Colored children were educated. The White children who lived in White Sulphur, as we affectionately called our town, went to the all-White school across town that the Colored students weren’t allowed to attend.

The reason that Colored children and White children went to separate schools dated way back to slavery. Many White people convinced themselves that Colored people were an inferior race and so justified using guns, whippings, beatings, rape, and other violence to enslave Colored people and force them to work for Whites. These attitudes and behaviors were prevalent for many decades after slavery ended, including in education.

In its 1857 Dred Scott decision, our nation’s highest court, the Supreme Court, ruled that Colored people were an “inferior and subordinate class of beings” as compared to Whites. Many White people then used the ruling to justify ongoing efforts to degrade and exploit Colored people. Then, in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Supreme Court legalized “separate but equal” facilities that were segregated by race. But everyone knew that separate also meant unequal. And that is why Mary McLeod Bethune was a two-room school located on a dirt road rather than a paved one like the all-White schools.

Despite these considerable obstacles, Colored people fought for our rights and took pride in our achievements. We engaged in self-help, educated ourselves and one another, and fought against laws and racial violence set up to oppress us and keep us “in our place,” as many White people described our inferior position in American society.

This brings me to Mary McLeod Bethune, a Colored woman born shortly after the end of slavery whose parents had been not only enslaved but also denied a formal education. The only one of her seventeen siblings able to obtain an education, she found knowledge to be so valuable that she shared what she was learning with everyone around her. She’d started teaching others back in the late 1800s. By the time I was born, on August 26, 1918, she was a famous educator and the founder of the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls (now Bethune-Cookman University), in Florida. She also helped lead the National Council of Negro Women, an organization focused on uplifting and improving the lives of Negroes by crusading for their rights to a quality education, the ability to vote, job opportunities, safety from racial violence, and more.

At the elementary school named in her honor, four grades were housed in each classroom. Mrs. Leftwich taught first through fourth grades in one room. That was the classroom that Charlie was in. Mr. Arter, the principal, taught fifth through seventh in the other, educating Horace and Margaret, whom I called Sister.

All totaled there were about twenty children in the first through fourth grades, and there was about the same number of older children. Now, far more Colored children than that lived in White Sulphur Springs, but many of them had to work to help their families have enough to eat. Though a high school existed to educate the White children, no school existed for Colored children after they finished the seventh grade.

I walked ninety-seven steps to the front door of the school, then used all my weight to open it wide enough to let myself in.

I then pulled up a chair next to Charlie, trying to be as quiet as possible.

“Why, what are you doing here, Katherine Coleman?” Mrs. Leftwich asked.

“I came to help my brother,” I said.

“Aww, Katherine, that’s sweet of you,” she said. “But Charlie is two years older than you. You haven’t even started school yet.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “But I know how to help him.”

“Okay, well, you just sit still and be quiet,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am,” I responded dutifully. I could tell she didn’t believe me.

Yet while my brother worked on his math lesson, I whispered and helped him as quietly as I could. Mrs. Leftwich kept coming back to Charlie’s seat and looking over our shoulders.

“You are helping him, aren’t you?” she asked after standing there for a while.

“Yes, ma’am,” I told her.

I’m not sure if she believed I was helping or if she was just trying to be nice to me. But Charlie and I figured out the answers together. When school was dismissed, I walked home with Charlie and the rest of the children and thought nothing of it.

![]()

One Saturday morning, I was helping Mama put dishes away when we heard one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight footsteps walking up the front stairs and onto the porch.

“Joylette, are you home?” a woman’s voice called out to my mother by her first name as her knuckles rapped on the door.

“Who’s there?” Mama answered as she finished drying a serving bowl and put down her dish towel.

“Rosa Leftwich,” said the voice.

What was the schoolteacher doing at our house?

“Oh, hello!” my mother answered, ushering Mrs. Leftwich into our home. “It’s good to see you. I hope that nothing’s wrong.”

“Oh, no, everything’s fine,” Mrs. Leftwich said.

“Good!” Mama said. “Well, Katherine and I were just drying dishes and straightening up. Why don’t you come join us in the kitchen?”

Mama pulled out a seat at the kitchen table. Mrs. Leftwich sat, and my mother poured her a cup of coffee and offered her some homemade applesauce.

“Katherine picked all the apples herself,” Mama informed her.

Well, after Mama had picked me up so I could reach them.

Mrs. Leftwich and Mama exchanged pleasantries, and I entertained myself counting and recounting the silverware.

“Well, I’m not sure if you are aware,” Mrs. Leftwich began, “but K-a-t-h-e-r-i-n-e came to the s-c-h-o-o-l last week.”

My mother mouthed something to Mrs. Leftwich and motioned to me. Perhaps Mrs. Leftwich had forgotten that I was in the room.

“The person tried to h-e-l-p C-h-a-r-l-i-e with his m-a-t-h.”

My mother pointed toward me.

Mrs. Leftwich looked at me and smiled.

I may have been only four, but I could understand everything she was saying. By then I could spell lots of words and already knew my multiplication tables.

Mama had been teaching me new words all the time. Between her training as a teacher and Daddy’s natural knack for numbers, education was highly valued in our home.

So I looked at Mama, and Mama looked at me. She shrugged.

“You don’t have to spell those words,” I told Mrs. Leftwich. “I know what you’re saying; I already know how to spell.”

Mrs. Leftwich’s eyes widened.

“You know how to spell?” she asked, looking at my mother in disbelief.

“Yes, ma’am,” I told her.

“So, do you understand what I was saying?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“What was I saying?”

“That I came to school and helped Charlie with math.”

“Well, I’ll be!” She gasped. “Who taught you how to spell?”

“Mama and Sister,” I answered.

“You’re serious!” Mrs. Leftwich exclaimed.

“Yes, ma’am. Mama teaches me spelling every night.”

Shocked, Mrs. Leftwich looked at my mother.

“We spell and we read and we learn math, don’t we, Katherine?” Mama said.

“Well, if you can already spell, Katherine, you need to be in school,” Mrs. Leftwich said.

“Yes, ma’am. That’s why I came to help Charlie. Sometimes he’s slow.”

“Katherine, how would you like it if I got some other children together and we start a kindergarten class?”

“I’d like to go to kindergarten,” I said. Being very inquisitive, no matter where I was, I always wanted to know what was going on. It was also important for me to understand why things were the way they were.

Apparently, after she left, Mrs. Leftwich talked to some other parents. After that she started working with a handful of children. That summer she started a kindergarten class in her home. Now, rather than being left with Mama at home, I went to class at Mrs. Leftwich’s.

When school began that fall, I started in the second grade. Suddenly I was a year ahead of Charlie and two years behind Sister, who was the smartest of all of us—even smarter than Horace, who was older than her. But Sister had a wayward eye—it didn’t look straight. By then I could already tell that people often underestimated her.

A few years after that they skipped me over fifth grade as well.

Horace and Sister remained ahead of me in school.

At first the other kids and their parents seemed to make a big deal about the fact that I’d been skipped forward in class. Everyone fussed over me at church. But then everyone got used to my being there and I went back to being Katherine.

I loved to learn so much that going to school alone wasn’t enough. I would go to the library as well. I loved to read, but the librarians allowed me to take out only one book at a time, though I could have read more than that.

Most days I would walk back home from school with the other kids. We would explore the forest, climb trees, or play jacks and kickball. When the first snow fell, we would sled down the hill behind our house, doing our best to avoid the apple tree at the bottom. Then I would go inside, thaw off, and help Mama put dinner on the table. After dinner we would work on our homework.

During the week, Mama would spend much of her day cooking. Back then, before you could buy prepared foods or go through the drive-through, it took a considerable part of the day to create three full-course meals from scratch, morning, noon, and night.

Mama kept chickens, which Daddy accused her of spoiling. Because when the time would come to eat one for dinner, she wouldn’t have the heart to kill it. So one of the boys would chase the chicken she wanted, catch it, and wring its neck—break it. Wringing a chicken’s neck doesn’t kill it right away, so she would put a big tub on top of it. Then we’d listen to the chicken running around like crazy under the tub until it died and the noise stopped—something we no longer do today because it’s inhumane, but back then it was just how we fed ourselves. At that point Mama would pick the chicken up and drop it into boiling water, which would loosen the feathers so that she could pull them off. Once the chicken had been plucked, she’d bake or fry it for dinner. In addition to fresh vegetables, our dinners often consisted of chicken or meat loaf, beans, potatoes, and gravy. We would buy milk, bacon, and bread from the grocery store. Often I’d be the one my parents would send on that errand.

Mama also spent time washing and ironing. She did our family’s laundry, but also that of some White families, as many other Colored women did to make ends meet. The laundry Mama took in included that of a White Episcopal priest, Reverend Eder, the priest in charge at St. Thomas Episcopal Church. Back then most people didn’t have washing machines, so Mama washed clothes by hand in a big green tub. She rubbed clothes against a washboard with a surface of corrugated metal to help get the dirt out. After she was finished washing, she attached porcelain rollers to the tub. She would then feed the clothes into the rollers and turn the crank to squeeze the excess water out so that she could hang the clothes on the line to dry.

Mama also could sew. She sewed our dresses. We didn’t have more than we needed, and everything we owned was practical. Back then flour came in big sacks. She would often make our dresses out of flour sacks.

On Sundays we attended St. James, where our family sat in the second row to the right. Daddy taught Sunday school, and I would help him. After church we’d come home for dinner. Sister would set the table, and afterward I’d help wash and dry the dishes. Then we’d go back for evening service.

Only one time, when we got a little older, did Daddy let us sit in the back of the church with the rest of the children our age. But during service, one of the other kids acted out and there was a small commotion. Though we weren’t involved, it got Daddy’s attention. He stood up, turned around, and looked at us.

“All of mine,” he said.

We knew what that meant, so we got up and moved to the front of the church. That’s just how Daddy was.

![]()

Dinnertime was important for our family, especially on Sundays, when the preacher and his wife often came over.

Daddy would bless our food, and then we would talk about our day as we sat at the table. Often that conversation included indirectly discussing racism. We would wonder aloud about things like why we couldn’t go the ice rink with the White children or why we had to sit in the balcony of the movie theater. There was no way to explain segregation’s daily humiliations and inequality, so there wasn’t much discussion about the reasons. You just had to know the rules, know your place, and stay in it. Doing that increased the odds that you would be safe and unharmed.

“You are no better than anyone else, but nobody else is better than you,” Daddy would emphasize to us over and over, even as he guided us to understand the restrictions of segregation.

Once dinner was over, we would clear the kitchen table and homework would begin. On Friday nights, for entertainment, we would often help Mama bake a cake or we would test our minds by working puzzles or playing checkers and other table games.

![]()

We hadn’t always lived in White Sulphur Springs. Until I was two, we resided in the country. Now that I look back upon it, it was country life that formed my family’s values and are instilled in me to this day.

Before we’d moved into town, Daddy had owned a very large farm and log-cabin farmhouse called Dutch Run located out on Big Draft Road in Oakhurst, a small rural community about three miles outside of town.

Now, how a Colored man back in that time came to own so much land and a house, I’m not quite sure, especially when he lacked much formal education. Some people say that he was the descendant of Colored people who had never been enslaved and as a result had been able to accumulate more than the average Colored person. Others say that one of his grandfathers was a White army colonel and one of his grandmothers was an enslaved Colored woman whom the colonel had forced himself on. As the story goes, the colonel subsequently provided for her and their mixed-race children. Perhaps some land from that union might have been handed down. It’s not hard to imagine that some sort of privilege may have been extended to him.

Looking back on things now, it is clear that as a very fair-skinned Negro, my daddy enjoyed some advantages that darker-skinned people didn’t. As his children, we were on the fair-skinned side as well. Back then people believed that one drop of Black blood tainted the “superior race,” but having White blood made you “better.”

Regardless, we lived at Dutch Run until I became a toddler. At that point he sold the farm. Then he moved us into 30 Church Street, the house he had built for us in town, which would make it easier for us to attend school.

Though we don’t know exactly how it happened, some White man must have purchased the land in town for Daddy; I don’t know who, how, or why. I do know that Colored people weren’t allowed to buy land back then.

What Daddy lacked in formal education, he made up for with his profound knowledge of and appreciation for the natural world. Until we’d moved into town, Daddy had been a farmer. He and Mama were very independent on the farm, raising just about everything our family needed to eat: beans, greens, peas, potatoes, corn, wheat, apples, grapes. We also had chickens and pigs.

Back then the only things Mama purchased from the store were coffee beans, granulated sugar, salt, and pepper. During the fall she would spend much of her day canning enough food to feed us over the winter.

Though farm life offered my parents a measure of independence that life in town didn’t, it was difficult then, and it remains difficult today. Farmers are dependent upon factors such as whether the sun shines enough or too much, when the rain comes and how much falls, and whether pests like the apple moth will undermine their crops and leave them with little to harvest, or whether frost or an early snowfall will leave them with scarcely anything to show for their months of work.

In the Allegheny Mountains it was essential to be able to feed your family, especially during the winters. That’s when the roads became treacherous and often impassable with snow and ice. Having canned enough food to feed yourself could mean the difference between surviving until spring or starving. This was where the laws of segregation would sometimes bow down to the laws of survival.

As a practical matter, even though the White people of West Virginia required Colored people to live in separate neighborhoods, out in Oakhurst that luxury didn’t always exist.

Plus, no one family could afford all of the different equipment—the plows, the threshing machines, the corn shellers, and so on—that they needed to farm all their land. So each family would buy one big piece of equipment, and they would all share it, regardless of race. That way everyone wasn’t investing in duplicate equipment or machines that would sit idle until the same time next year. Come harvest time, the entire community would gather together and work in one another’s fields—the White families as well as Colored families cooperating to ensure that everyone survived.

Women and men often took on gender roles that were more traditional and distinct than their roles are today. The men typically worked in the fields, while women would manage the family’s garden and kitchen. Cultivating a large garden, too, was difficult work—stooping over long rows of peas or collard greens, or keeping the rabbits or deer from eating your food. It often took all day to create every meal from scratch, laboring in a hot kitchen to cook enough sustenance to support dawn-to-dusk physical labor.

It wasn’t unusual during harvest season for women to prepare breakfast and dinner at home, then come together to serve the midday meal, everyone gathering in one house to eat—typically the house of the family whose fields were being worked. In this way everyone was well fed and could get back to work more quickly than if each person walked or rode his horse home to eat and then came back after lunch. Saving precious daylight hours could mean the difference between harvesting the food before the first frost or not, and having enough nourishment for the winter or not.

Since survival was a practical matter, some of the rules of segregation that were strictly enforced in other locations didn’t exist to the same extent in Oakhurst. Though racial segregation was imposed in town, during planting season and the harvest, Colored people and Whites became just a community of farmers coming together to help one another live. Though country children attended segregated schools during the daytime, after school we played together.

The belief that people should convene to help one another was valued in my family. You always lent a hand to other human beings. Perhaps that’s also how I learned from an early age to not always adhere to the customs of the color line.

When Daddy wasn’t farming, he was often cutting trees. There were lots of big trees all around the family farm and the region, where during the summer everything turned emerald green. In fact, the Meadow River Lumber Company operated the world’s largest sawmill not too far away, along the Meadow River between the Sewell and Simms Mountains, at the western edge of Greenbrier County.

Cutting down a tree may look easy, but it’s really hard. You have to know things like whether the tree is solid or whether any of it is rotten in the middle, the type of wood you’re cutting, and the angle at which you want to make it fall. You cut a Norway maple differently from a sycamore maple. If you don’t calculate that right, the tree can fall onto your house—or onto your head and kill you. Even today, logging is very dangerous work.

Daddy and his crew would cut trees down, then use his horse-drawn wagon to haul lumber from the logging camps to the mill for cutting. Daddy owned workhorses and show horses. His workhorses hauled timber around. His show horses, who were named Bill and Frank, transported our family in a horse-drawn buggy. He would also use the buggy to carry White people around, a way of making additional money.

We lived in horse country, and Daddy was a horse man. He loved horses, and somehow horses knew that they could trust him. White people would bring him their horses and he would tell them what was wrong. A horse whisperer was what they called him. Daddy was like a veterinarian without a formal degree. He could calm horses down and make animals well. Daddy would wake up in the middle of the night because somehow while he was sleeping he would hear a heifer—a cow—moaning because she was in labor.

“That animal is in trouble.” He’d know based on the sound of her cries.

He would get out of bed and go help the heifer deliver her baby.

Daddy also had common sense. He’d look at the color of the sky at sunset and know what weather lay on the horizon: “Red sky at night, sailors’ delight; red sky in the morning, sailors take warning.” On weekends, he and I would often head back out to the country, going on long walks along dirt paths, across grassy knolls, and over the forest floor carpeted with leaves, gold and brown. We would ramble through the hills, searching for wild blackberries and huckleberries so Mama could bake a pie. Daddy would point out the moths, carpenter ants, and roly-poly bugs beneath the bark of dead logs. I would help him pick out flat rocks to skip atop the chilly water cascading down the creek.

On one particular journey, when I was four, we stopped for a moment to catch our breath.

“What’s this warm thing I’m standing on?” I asked, sensing something unusual beneath my bare feet.

Daddy bent over to look.

“Be still. Don’t move!” he said, standing quickly as he reached over his shoulder and pulled out his rifle—all in one smooth movement.

BAM!

I jumped, and a spray of leaves and dirt flew up into the air. Then Daddy kicked at something with his boot.

“That was a snake, a copperhead,” he told me as he picked up what was left of the snake with a stick. “Watch out for copperheads, Katherine; they’re poisonous.”

I inched closer to the stick. The snake’s body was draped over it.

“You can always tell a copperhead by its markings,” Daddy told me. “Do you see that hourglass marking that’s skinny in the middle and wider on its sides?”

“Yes,” I said.

“That’s how you can tell them.”

I always felt so safe whenever Daddy was near.

![]()

Though life on the farm had been simple and carefree, in town the lines between the races were much clearer. While Main Street was the downtown for the entire city, parts of White Sulphur were distinctly Colored.

Daddy had built our new home, called the Big House, in the main Colored part of town. The Big House in White Sulphur was better than Dutch Run. There were four rooms on the ground floor and a main stairway to the second floor. Upstairs there were four bedrooms: one for our mother and father, one for the boys, one for us girls, and an extra one. The bathroom was upstairs on the second floor. That house was large by anyone’s standards.

Wide porches—one upstairs and one downstairs—ran the expanse of the front of the house. The ceiling of each was painted sky blue. Sitting there, you would see Colored life in White Sulphur pass by. I loved to relax on the porch with my father.

![]()

Our house on Church Street.

“Good morning, Mr. Coleman,” people would say as they walked by.

“Good morning,” my father would reply.

One of the best things about our house was that it was the first on the block to have indoor plumbing; everyone else used the bathroom in their outhouse, a shack with a hole in the ground and a seat you would sit on as you relieved yourself. We also had the first telephone on Church Street. Our phone number was 228. It was a party line, which meant you shared your line with other people. The calls came in to a central operator sitting at a switchboard at the phone company downtown. The operator would pick up the phone and manually route the call to your house. If somebody else was on the line, you had to wait. If it was an emergency, you could ask the other person to hang up. But people didn’t stay on the phone forever, as they do today.

Church Street was about two city blocks long by today’s standards.

We had one White neighbor, who lived on the far end on our side. We didn’t really know him. The White people in White Sulphur didn’t bother you, but they didn’t mix with you either.

Walking from that end up in the direction of our house, you’d pass two homes before you got to that of Mr. Arter. Then you’d pass First Baptist and Haywood’s, the only restaurant in town where Colored people could eat. You’d walk by four more houses before you got to our house. Four houses beyond us you’d run into St. James, where Church Street dead-ended at Barton. Crump Barbershop, where Daddy got his hair cut, was across the street from Haywood’s. Daddy’s mother lived in a little one-story house next door to Crump’s. Daddy kept a beautiful garden in her backyard, with rows of string beans, rhubarb, potatoes, onions, scallions, carrots, radishes, and beans. We ate from that garden during much of the year.

The Baptist and Methodist churches were the only ones that Colored people in White Sulphur could attend. Back then, each had a part-time preacher who would deliver service on two Sundays a month. The Methodist preacher preached on the first and third Sunday, the Baptist preacher on the second and fourth. Since most everyone went to church every week, that meant the Methodists attended the Baptist church and the Baptists attended the Methodist church on the weeks when their pastor wasn’t preaching. During the summer they held a combined picnic. They also combined their vacation Bible school, where children learned about the Bible during summer vacation.

St. Thomas Episcopal Church, where Reverend Eder presided, was on Main Street in the center of town. But only White people could attend. There was only one God, but segregation meant that White people and Colored people couldn’t worship Him in the same place. We let God be the judge of that.

Though people lived there all year long, White Sulphur Springs was a vacation town. Known as the “Queen of the Watering Places” in the South, it was where the well-heeled vacationers from Virginia’s coast and other Southern locations would escape summer’s heat and humidity. Because it was located two thousand feet high in the mountains, White Sulphur’s climate was much more comfortable than other southerly regions were.

Our town got its name from a freshwater mineral bath that bubbled up from deep underground. Before the European settlers arrived and killed off most of the indigenous people, Greenbrier County was part of the Can-tuc-kee territory, where the Shawnee and Cherokee peoples lived. According to legend, a young Shawnee couple slipped away to spend time alone. Their chief caught them together unsupervised, became angry, and shot two arrows toward them. The first killed the boy; the second whistled past the girl, pierced the ground, and supposedly created the springs. After the last drop of spring water has been drunk, the young woman’s suitor is supposed to return to life.

That’s the story according to legend. Scientifically, a thermal spring comes from geothermally heated groundwater rising from the Earth’s crust.

Regardless of the water’s source, for centuries people believed that it cured rheumatism’s stiff joints, as well as skin problems, respiratory illnesses, menstrual cramps, fevers, and so on. Folks would travel from across the South and beyond in order to visit the spring. Our town was also known for the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, a bloody conflict fought during the Civil War, where almost four hundred Union and Confederate soldiers were lost.

During the mid-1800s, an impressive six-story, snow-colored resort called the Greenbrier Hotel was built at the springs. Indeed, the Greenbrier looked so much like the White House that it was once known as “Old White.” Before the Civil War, five sitting presidents vacationed there, as did judges, lawyers, diplomats, slaveholders, and merchants—mostly from Southern states. Only two years before I was born, in 1916, President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson spent Easter at the Greenbrier. The grandparents of President John F. Kennedy, who wasn’t yet born, honeymooned there when I was two months old.

During the years right after my birth and well into the Roaring Twenties, the Greenbrier was very popular among the industrialists and other extremely wealthy people in American society. The C&O Railway owned the two-hundred-and-fifty-room property and delivered its guests—who, depending on the season, would vacation in places like the Greenbrier; Newport, Rhode Island; and Palm Beach, Florida—in their private coaches right to the resort’s front door. Indeed, the railroad stop was located right across Main Street from the resort. Passengers would step off the train and into a horse and carriage to be ridden across the road, their feet not even touching the ground. We townsfolk would gaze longingly at the visitors dressed so formally. The women would be attired in colorful ball gowns—blush pink, scarlet, sapphire blue, and forest green—and the men in tuxedos. From the outside, they seemed to live a wonderful life. The rest of us had to travel by foot, saddle up a horse, or maybe ride a horse and buggy to get around.

Daddy moved us into the town that developed around the Greenbrier, to make it easy for us to go to school. His sixth-grade education was not unusual. He had been born at a time when education was a luxury for Colored people, particularly in rural areas. Because they were often denied the opportunity to receive schooling around the turn of the twentieth century, when Daddy was born, about half of Colored people at that time were unable to read.

Because his own education had been prohibited, his children’s was extremely important to him. If there was one thing Daddy would say, it was that he didn’t want to raise any “dumb, ignorant children.” He was determined that his children would go to college.

The wealthy guests of the Greenbrier created many sources of income for everyone, regardless of race. Whether at the Virginia Electric Company, the bank, or the Episcopal church, all of which Daddy now cleaned, in town there was work. He also took care of several rich people’s summer homes during the fall and winter when they relocated to warmer places. They trusted my father with the keys to their homes, and he took care of everything during winter months when the homes were uninhabited. His honorable reputation preceded him, and his word was his bond—you could always trust what he said. Come spring, he would prepare the houses for the families to return during vacation season. He also drove rich people around with his show horses and buggy, which were way prettier than those at the Greenbrier.

Colored people were allowed to work at the Greenbrier, but they weren’t permitted to stay there as guests. Colored women served as maids, babysitters, servers, and seamstresses. They unpacked trunks and pressed people’s clothes. Colored men labored as bellmen and servers and busboys and porters, which were some of the best jobs they were able to obtain during those times. This type of work was also among the least hazardous—far safer and cleaner than what could be found in the coal mines, one of the area’s major employers that offered some of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Daddy worked at the Greenbriar as a bellman in addition to doing side jobs.

I would go everywhere with Daddy. I especially loved accompanying him to his cleaning or handyman work or as he ran his errands downtown, where the White people worked.

“Good morning, Mrs. Burr,” he would say to one of the White ladies with a tip of the hat, his cleaning bucket hanging from his free arm. Mrs. Burr’s husband owned the Esso, the only gas station in town.

“Good morning, Josh,” Mrs. Burr and other White women would reply, calling him by his first name.

Daddy was well respected; however, segregation had its rules, laws, and conventions. Although Colored people addressed Daddy as “mister,” White people, including children, called him by his first name.

Even though Greenbrier’s jobs were good for that era, Daddy didn’t want his children to have to work there when they grew up, experiencing either its snubs or the perilous accusations that White people could capriciously make against Colored people—you never knew when.

Like many other Colored people of that era, he saw education as the pathway his children could follow to escape indignities and dangers, large and small. So for two years he sent Margaret away to continue her education. Then Daddy and Mama decided to take a leap of faith.

CHAPTER 1

It’s not every day you wake up with a mission on your mind, but I had a mission and I was determined to accomplish it. Except for the sound of Mama humming and the clinking of dishes as she washed them in the sink, the house was quiet. Moments earlier Daddy had left for work and my brothers and sister had set off to school. As I sat at the kitchen table still fiddling with my oatmeal, I couldn’t get my brother Charlie out of my mind. I kept revisiting the scene at the kitchen table the night before, when he’d struggled with his math homework.

First Mama had tried to assist him with it. Back before she’d had Horace, Margaret, Charlie, and me, she had been a teacher. She should have been able to help him figure out his schoolwork.

But the way he had slumped over onto one elbow had signaled that he was feeling frustrated.

“Sit up straight,” Mama had told him, and he did.

Horace and Margaret were steadily scribbling away at their assignments, apparently unbothered by Charlie’s challenges.

“Maybe you can explain it better than I can, Josh,” Mama said to Daddy, who was sitting in the front room reading the White Sulphur Sentinel, our town’s newspaper. Daddy loved to read the paper. He also read the almanac. Mama adored us, but she was very orderly and from time to time she could be a bit strict. Our father was a little more relaxed.

My parents, Joshua and Joylette Coleman.

Daddy set the paper down and slowly unfurled himself from his favorite chair. More than six feet tall, he towered above most everyone.

“Let’s see what we can do here, Son,” he said, sitting down and scooting closer to his youngest son, the chair scraping loudly across the oak floor.

Daddy put his left arm around Charlie, who leaned into him.

“I can’t figure it out,” Charlie said, his lack of confidence evident in his voice.

“Yes, you can,” Daddy told him. “We just have to explain it so that you get it. Once you understand the background of any idea, you can figure any problem out for yourself.”

Daddy’s personality could be more comforting than Mama’s. Numbers were also Daddy’s strength. He may have had only a sixth-grade education, but he was really good with figures. Envisioning things was one of his strong points. He was so good that he could look at an entire oak, pine, or even a chestnut tree, and tell you how many logs it would yield once it had been cut down. We even lived in a home he had built for us.

Charlie was two years older than me, but for some reason he seemed to be a little slow. At least, that’s what I thought back then. I would be well into adulthood before I discovered that the issue wasn’t that he was slow. The truth of the matter was that I was fast. It turned out that I was very gifted in math.

Math had always come easily to me. I loved numbers and numbers loved me. They followed me everywhere. No matter what I did, I was always finding something to count: the floorboards, the cracks in the sidewalk, the trees as I walked by, the train cars stacked with timber and those piled with coal that lumbered along the edge of our town each day. The number of times the train engineers blew the whistle as they traveled through the trees, echoing off the granite bedrock that rose above us and formed the valley within which our town, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, was nestled.

Me at age two with my brothers and sister.

That was just the way that my mind worked. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight forks. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight plates. One, two, three serving spoons. Mama was very well organized, but my mind took her sense of order one step further. I always knew how many of everything there were. Things were there and could be counted and accounted for, so that’s what I did.

So when Charlie found it hard to understand numbers, it really bothered me. And it disturbed me even more when he didn’t understand even after both Mama and Daddy had tried to teach them to him.

At that point I decided to take things into my own hands. And that was why, even though I was only four years old, I told my plan to Mama, then walked out the front door, then four steps across the porch, eight steps down the front stairs, and five steps down the front walk, and set off toward the school.

As I marched out of our front yard and turned onto the sidewalk, I waved at Mrs. Hopkins, who was sweeping the front porch of her family’s two-story house across our street. Church Street was the center of Colored life in White Sulphur Springs. Back then the same people we now call African American or Black were called Colored or Negro. (It’s important not to use those words to describe people today or you will certainly offend them.)

I strode slightly uphill past five houses and St. James United Methodist Church, where we worshipped, to the corner of Barton Road. That’s where Church Street ended, as what had been a slight rise suddenly became very steep—too steep to sled after the snow fell. It was covered with maple, sycamore, and pine trees, and during the spring and summer months, grass.

About one hundred yards up that hill ran the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway tracks, where black and navy-blue trains with a yellow Cheshire cat painted on them rumbled through town twice daily, morning and evening. The C&O trains carried coal, lumber, and supplies as well as people from the Virginia coast (which was about six hours southeast) northwestward through the Allegheny Mountains, part of the Appalachian mountain range of West Virginia and southern Ohio. The C&O then carried its load over the Ohio River, across that state on into Detroit and other parts of Michigan. Some trains traveled even farther westward into Indiana and on to the growing industrial cities of Gary, Indiana, and Chicago, Illinois.

A passenger train also rolled through town, carrying not only travelers of modest means but also the well-appointed private coaches that the wealthy magnates of that era owned and used to travel around the country.

I turned left onto Barton and followed it one block until I came to a dirt path on my right. About one hundred feet up that path sat the Mary McLeod Bethune Grade School, the white wooden two-room schoolhouse where our town’s Colored children were educated. The White children who lived in White Sulphur, as we affectionately called our town, went to the all-White school across town that the Colored students weren’t allowed to attend.

The reason that Colored children and White children went to separate schools dated way back to slavery. Many White people convinced themselves that Colored people were an inferior race and so justified using guns, whippings, beatings, rape, and other violence to enslave Colored people and force them to work for Whites. These attitudes and behaviors were prevalent for many decades after slavery ended, including in education.

In its 1857 Dred Scott decision, our nation’s highest court, the Supreme Court, ruled that Colored people were an “inferior and subordinate class of beings” as compared to Whites. Many White people then used the ruling to justify ongoing efforts to degrade and exploit Colored people. Then, in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Supreme Court legalized “separate but equal” facilities that were segregated by race. But everyone knew that separate also meant unequal. And that is why Mary McLeod Bethune was a two-room school located on a dirt road rather than a paved one like the all-White schools.

Despite these considerable obstacles, Colored people fought for our rights and took pride in our achievements. We engaged in self-help, educated ourselves and one another, and fought against laws and racial violence set up to oppress us and keep us “in our place,” as many White people described our inferior position in American society.

This brings me to Mary McLeod Bethune, a Colored woman born shortly after the end of slavery whose parents had been not only enslaved but also denied a formal education. The only one of her seventeen siblings able to obtain an education, she found knowledge to be so valuable that she shared what she was learning with everyone around her. She’d started teaching others back in the late 1800s. By the time I was born, on August 26, 1918, she was a famous educator and the founder of the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls (now Bethune-Cookman University), in Florida. She also helped lead the National Council of Negro Women, an organization focused on uplifting and improving the lives of Negroes by crusading for their rights to a quality education, the ability to vote, job opportunities, safety from racial violence, and more.

At the elementary school named in her honor, four grades were housed in each classroom. Mrs. Leftwich taught first through fourth grades in one room. That was the classroom that Charlie was in. Mr. Arter, the principal, taught fifth through seventh in the other, educating Horace and Margaret, whom I called Sister.

All totaled there were about twenty children in the first through fourth grades, and there was about the same number of older children. Now, far more Colored children than that lived in White Sulphur Springs, but many of them had to work to help their families have enough to eat. Though a high school existed to educate the White children, no school existed for Colored children after they finished the seventh grade.

I walked ninety-seven steps to the front door of the school, then used all my weight to open it wide enough to let myself in.

I then pulled up a chair next to Charlie, trying to be as quiet as possible.

“Why, what are you doing here, Katherine Coleman?” Mrs. Leftwich asked.

“I came to help my brother,” I said.

“Aww, Katherine, that’s sweet of you,” she said. “But Charlie is two years older than you. You haven’t even started school yet.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “But I know how to help him.”

“Okay, well, you just sit still and be quiet,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am,” I responded dutifully. I could tell she didn’t believe me.

Yet while my brother worked on his math lesson, I whispered and helped him as quietly as I could. Mrs. Leftwich kept coming back to Charlie’s seat and looking over our shoulders.

“You are helping him, aren’t you?” she asked after standing there for a while.

“Yes, ma’am,” I told her.

I’m not sure if she believed I was helping or if she was just trying to be nice to me. But Charlie and I figured out the answers together. When school was dismissed, I walked home with Charlie and the rest of the children and thought nothing of it.

One Saturday morning, I was helping Mama put dishes away when we heard one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight footsteps walking up the front stairs and onto the porch.

“Joylette, are you home?” a woman’s voice called out to my mother by her first name as her knuckles rapped on the door.

“Who’s there?” Mama answered as she finished drying a serving bowl and put down her dish towel.

“Rosa Leftwich,” said the voice.

What was the schoolteacher doing at our house?

“Oh, hello!” my mother answered, ushering Mrs. Leftwich into our home. “It’s good to see you. I hope that nothing’s wrong.”

“Oh, no, everything’s fine,” Mrs. Leftwich said.

“Good!” Mama said. “Well, Katherine and I were just drying dishes and straightening up. Why don’t you come join us in the kitchen?”

Mama pulled out a seat at the kitchen table. Mrs. Leftwich sat, and my mother poured her a cup of coffee and offered her some homemade applesauce.

“Katherine picked all the apples herself,” Mama informed her.

Well, after Mama had picked me up so I could reach them.

Mrs. Leftwich and Mama exchanged pleasantries, and I entertained myself counting and recounting the silverware.

“Well, I’m not sure if you are aware,” Mrs. Leftwich began, “but K-a-t-h-e-r-i-n-e came to the s-c-h-o-o-l last week.”

My mother mouthed something to Mrs. Leftwich and motioned to me. Perhaps Mrs. Leftwich had forgotten that I was in the room.

“The person tried to h-e-l-p C-h-a-r-l-i-e with his m-a-t-h.”

My mother pointed toward me.

Mrs. Leftwich looked at me and smiled.

I may have been only four, but I could understand everything she was saying. By then I could spell lots of words and already knew my multiplication tables.

Mama had been teaching me new words all the time. Between her training as a teacher and Daddy’s natural knack for numbers, education was highly valued in our home.

So I looked at Mama, and Mama looked at me. She shrugged.

“You don’t have to spell those words,” I told Mrs. Leftwich. “I know what you’re saying; I already know how to spell.”

Mrs. Leftwich’s eyes widened.

“You know how to spell?” she asked, looking at my mother in disbelief.

“Yes, ma’am,” I told her.

“So, do you understand what I was saying?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“What was I saying?”

“That I came to school and helped Charlie with math.”

“Well, I’ll be!” She gasped. “Who taught you how to spell?”

“Mama and Sister,” I answered.

“You’re serious!” Mrs. Leftwich exclaimed.

“Yes, ma’am. Mama teaches me spelling every night.”

Shocked, Mrs. Leftwich looked at my mother.

“We spell and we read and we learn math, don’t we, Katherine?” Mama said.

“Well, if you can already spell, Katherine, you need to be in school,” Mrs. Leftwich said.

“Yes, ma’am. That’s why I came to help Charlie. Sometimes he’s slow.”

“Katherine, how would you like it if I got some other children together and we start a kindergarten class?”

“I’d like to go to kindergarten,” I said. Being very inquisitive, no matter where I was, I always wanted to know what was going on. It was also important for me to understand why things were the way they were.

Apparently, after she left, Mrs. Leftwich talked to some other parents. After that she started working with a handful of children. That summer she started a kindergarten class in her home. Now, rather than being left with Mama at home, I went to class at Mrs. Leftwich’s.

When school began that fall, I started in the second grade. Suddenly I was a year ahead of Charlie and two years behind Sister, who was the smartest of all of us—even smarter than Horace, who was older than her. But Sister had a wayward eye—it didn’t look straight. By then I could already tell that people often underestimated her.

A few years after that they skipped me over fifth grade as well.

Horace and Sister remained ahead of me in school.

At first the other kids and their parents seemed to make a big deal about the fact that I’d been skipped forward in class. Everyone fussed over me at church. But then everyone got used to my being there and I went back to being Katherine.

I loved to learn so much that going to school alone wasn’t enough. I would go to the library as well. I loved to read, but the librarians allowed me to take out only one book at a time, though I could have read more than that.

Most days I would walk back home from school with the other kids. We would explore the forest, climb trees, or play jacks and kickball. When the first snow fell, we would sled down the hill behind our house, doing our best to avoid the apple tree at the bottom. Then I would go inside, thaw off, and help Mama put dinner on the table. After dinner we would work on our homework.

During the week, Mama would spend much of her day cooking. Back then, before you could buy prepared foods or go through the drive-through, it took a considerable part of the day to create three full-course meals from scratch, morning, noon, and night.

Mama kept chickens, which Daddy accused her of spoiling. Because when the time would come to eat one for dinner, she wouldn’t have the heart to kill it. So one of the boys would chase the chicken she wanted, catch it, and wring its neck—break it. Wringing a chicken’s neck doesn’t kill it right away, so she would put a big tub on top of it. Then we’d listen to the chicken running around like crazy under the tub until it died and the noise stopped—something we no longer do today because it’s inhumane, but back then it was just how we fed ourselves. At that point Mama would pick the chicken up and drop it into boiling water, which would loosen the feathers so that she could pull them off. Once the chicken had been plucked, she’d bake or fry it for dinner. In addition to fresh vegetables, our dinners often consisted of chicken or meat loaf, beans, potatoes, and gravy. We would buy milk, bacon, and bread from the grocery store. Often I’d be the one my parents would send on that errand.

Mama also spent time washing and ironing. She did our family’s laundry, but also that of some White families, as many other Colored women did to make ends meet. The laundry Mama took in included that of a White Episcopal priest, Reverend Eder, the priest in charge at St. Thomas Episcopal Church. Back then most people didn’t have washing machines, so Mama washed clothes by hand in a big green tub. She rubbed clothes against a washboard with a surface of corrugated metal to help get the dirt out. After she was finished washing, she attached porcelain rollers to the tub. She would then feed the clothes into the rollers and turn the crank to squeeze the excess water out so that she could hang the clothes on the line to dry.

Mama also could sew. She sewed our dresses. We didn’t have more than we needed, and everything we owned was practical. Back then flour came in big sacks. She would often make our dresses out of flour sacks.

On Sundays we attended St. James, where our family sat in the second row to the right. Daddy taught Sunday school, and I would help him. After church we’d come home for dinner. Sister would set the table, and afterward I’d help wash and dry the dishes. Then we’d go back for evening service.

Only one time, when we got a little older, did Daddy let us sit in the back of the church with the rest of the children our age. But during service, one of the other kids acted out and there was a small commotion. Though we weren’t involved, it got Daddy’s attention. He stood up, turned around, and looked at us.

“All of mine,” he said.

We knew what that meant, so we got up and moved to the front of the church. That’s just how Daddy was.

Dinnertime was important for our family, especially on Sundays, when the preacher and his wife often came over.

Daddy would bless our food, and then we would talk about our day as we sat at the table. Often that conversation included indirectly discussing racism. We would wonder aloud about things like why we couldn’t go the ice rink with the White children or why we had to sit in the balcony of the movie theater. There was no way to explain segregation’s daily humiliations and inequality, so there wasn’t much discussion about the reasons. You just had to know the rules, know your place, and stay in it. Doing that increased the odds that you would be safe and unharmed.

“You are no better than anyone else, but nobody else is better than you,” Daddy would emphasize to us over and over, even as he guided us to understand the restrictions of segregation.

Once dinner was over, we would clear the kitchen table and homework would begin. On Friday nights, for entertainment, we would often help Mama bake a cake or we would test our minds by working puzzles or playing checkers and other table games.

We hadn’t always lived in White Sulphur Springs. Until I was two, we resided in the country. Now that I look back upon it, it was country life that formed my family’s values and are instilled in me to this day.

Before we’d moved into town, Daddy had owned a very large farm and log-cabin farmhouse called Dutch Run located out on Big Draft Road in Oakhurst, a small rural community about three miles outside of town.

Now, how a Colored man back in that time came to own so much land and a house, I’m not quite sure, especially when he lacked much formal education. Some people say that he was the descendant of Colored people who had never been enslaved and as a result had been able to accumulate more than the average Colored person. Others say that one of his grandfathers was a White army colonel and one of his grandmothers was an enslaved Colored woman whom the colonel had forced himself on. As the story goes, the colonel subsequently provided for her and their mixed-race children. Perhaps some land from that union might have been handed down. It’s not hard to imagine that some sort of privilege may have been extended to him.

Looking back on things now, it is clear that as a very fair-skinned Negro, my daddy enjoyed some advantages that darker-skinned people didn’t. As his children, we were on the fair-skinned side as well. Back then people believed that one drop of Black blood tainted the “superior race,” but having White blood made you “better.”

Regardless, we lived at Dutch Run until I became a toddler. At that point he sold the farm. Then he moved us into 30 Church Street, the house he had built for us in town, which would make it easier for us to attend school.

Though we don’t know exactly how it happened, some White man must have purchased the land in town for Daddy; I don’t know who, how, or why. I do know that Colored people weren’t allowed to buy land back then.

What Daddy lacked in formal education, he made up for with his profound knowledge of and appreciation for the natural world. Until we’d moved into town, Daddy had been a farmer. He and Mama were very independent on the farm, raising just about everything our family needed to eat: beans, greens, peas, potatoes, corn, wheat, apples, grapes. We also had chickens and pigs.

Back then the only things Mama purchased from the store were coffee beans, granulated sugar, salt, and pepper. During the fall she would spend much of her day canning enough food to feed us over the winter.

Though farm life offered my parents a measure of independence that life in town didn’t, it was difficult then, and it remains difficult today. Farmers are dependent upon factors such as whether the sun shines enough or too much, when the rain comes and how much falls, and whether pests like the apple moth will undermine their crops and leave them with little to harvest, or whether frost or an early snowfall will leave them with scarcely anything to show for their months of work.

In the Allegheny Mountains it was essential to be able to feed your family, especially during the winters. That’s when the roads became treacherous and often impassable with snow and ice. Having canned enough food to feed yourself could mean the difference between surviving until spring or starving. This was where the laws of segregation would sometimes bow down to the laws of survival.

As a practical matter, even though the White people of West Virginia required Colored people to live in separate neighborhoods, out in Oakhurst that luxury didn’t always exist.

Plus, no one family could afford all of the different equipment—the plows, the threshing machines, the corn shellers, and so on—that they needed to farm all their land. So each family would buy one big piece of equipment, and they would all share it, regardless of race. That way everyone wasn’t investing in duplicate equipment or machines that would sit idle until the same time next year. Come harvest time, the entire community would gather together and work in one another’s fields—the White families as well as Colored families cooperating to ensure that everyone survived.

Women and men often took on gender roles that were more traditional and distinct than their roles are today. The men typically worked in the fields, while women would manage the family’s garden and kitchen. Cultivating a large garden, too, was difficult work—stooping over long rows of peas or collard greens, or keeping the rabbits or deer from eating your food. It often took all day to create every meal from scratch, laboring in a hot kitchen to cook enough sustenance to support dawn-to-dusk physical labor.

It wasn’t unusual during harvest season for women to prepare breakfast and dinner at home, then come together to serve the midday meal, everyone gathering in one house to eat—typically the house of the family whose fields were being worked. In this way everyone was well fed and could get back to work more quickly than if each person walked or rode his horse home to eat and then came back after lunch. Saving precious daylight hours could mean the difference between harvesting the food before the first frost or not, and having enough nourishment for the winter or not.

Since survival was a practical matter, some of the rules of segregation that were strictly enforced in other locations didn’t exist to the same extent in Oakhurst. Though racial segregation was imposed in town, during planting season and the harvest, Colored people and Whites became just a community of farmers coming together to help one another live. Though country children attended segregated schools during the daytime, after school we played together.

The belief that people should convene to help one another was valued in my family. You always lent a hand to other human beings. Perhaps that’s also how I learned from an early age to not always adhere to the customs of the color line.

When Daddy wasn’t farming, he was often cutting trees. There were lots of big trees all around the family farm and the region, where during the summer everything turned emerald green. In fact, the Meadow River Lumber Company operated the world’s largest sawmill not too far away, along the Meadow River between the Sewell and Simms Mountains, at the western edge of Greenbrier County.

Cutting down a tree may look easy, but it’s really hard. You have to know things like whether the tree is solid or whether any of it is rotten in the middle, the type of wood you’re cutting, and the angle at which you want to make it fall. You cut a Norway maple differently from a sycamore maple. If you don’t calculate that right, the tree can fall onto your house—or onto your head and kill you. Even today, logging is very dangerous work.

Daddy and his crew would cut trees down, then use his horse-drawn wagon to haul lumber from the logging camps to the mill for cutting. Daddy owned workhorses and show horses. His workhorses hauled timber around. His show horses, who were named Bill and Frank, transported our family in a horse-drawn buggy. He would also use the buggy to carry White people around, a way of making additional money.

We lived in horse country, and Daddy was a horse man. He loved horses, and somehow horses knew that they could trust him. White people would bring him their horses and he would tell them what was wrong. A horse whisperer was what they called him. Daddy was like a veterinarian without a formal degree. He could calm horses down and make animals well. Daddy would wake up in the middle of the night because somehow while he was sleeping he would hear a heifer—a cow—moaning because she was in labor.

“That animal is in trouble.” He’d know based on the sound of her cries.

He would get out of bed and go help the heifer deliver her baby.

Daddy also had common sense. He’d look at the color of the sky at sunset and know what weather lay on the horizon: “Red sky at night, sailors’ delight; red sky in the morning, sailors take warning.” On weekends, he and I would often head back out to the country, going on long walks along dirt paths, across grassy knolls, and over the forest floor carpeted with leaves, gold and brown. We would ramble through the hills, searching for wild blackberries and huckleberries so Mama could bake a pie. Daddy would point out the moths, carpenter ants, and roly-poly bugs beneath the bark of dead logs. I would help him pick out flat rocks to skip atop the chilly water cascading down the creek.

On one particular journey, when I was four, we stopped for a moment to catch our breath.

“What’s this warm thing I’m standing on?” I asked, sensing something unusual beneath my bare feet.

Daddy bent over to look.

“Be still. Don’t move!” he said, standing quickly as he reached over his shoulder and pulled out his rifle—all in one smooth movement.

BAM!

I jumped, and a spray of leaves and dirt flew up into the air. Then Daddy kicked at something with his boot.

“That was a snake, a copperhead,” he told me as he picked up what was left of the snake with a stick. “Watch out for copperheads, Katherine; they’re poisonous.”

I inched closer to the stick. The snake’s body was draped over it.

“You can always tell a copperhead by its markings,” Daddy told me. “Do you see that hourglass marking that’s skinny in the middle and wider on its sides?”

“Yes,” I said.

“That’s how you can tell them.”

I always felt so safe whenever Daddy was near.

Though life on the farm had been simple and carefree, in town the lines between the races were much clearer. While Main Street was the downtown for the entire city, parts of White Sulphur were distinctly Colored.

Daddy had built our new home, called the Big House, in the main Colored part of town. The Big House in White Sulphur was better than Dutch Run. There were four rooms on the ground floor and a main stairway to the second floor. Upstairs there were four bedrooms: one for our mother and father, one for the boys, one for us girls, and an extra one. The bathroom was upstairs on the second floor. That house was large by anyone’s standards.

Wide porches—one upstairs and one downstairs—ran the expanse of the front of the house. The ceiling of each was painted sky blue. Sitting there, you would see Colored life in White Sulphur pass by. I loved to relax on the porch with my father.

Our house on Church Street.

“Good morning, Mr. Coleman,” people would say as they walked by.

“Good morning,” my father would reply.

One of the best things about our house was that it was the first on the block to have indoor plumbing; everyone else used the bathroom in their outhouse, a shack with a hole in the ground and a seat you would sit on as you relieved yourself. We also had the first telephone on Church Street. Our phone number was 228. It was a party line, which meant you shared your line with other people. The calls came in to a central operator sitting at a switchboard at the phone company downtown. The operator would pick up the phone and manually route the call to your house. If somebody else was on the line, you had to wait. If it was an emergency, you could ask the other person to hang up. But people didn’t stay on the phone forever, as they do today.

Church Street was about two city blocks long by today’s standards.

We had one White neighbor, who lived on the far end on our side. We didn’t really know him. The White people in White Sulphur didn’t bother you, but they didn’t mix with you either.

Walking from that end up in the direction of our house, you’d pass two homes before you got to that of Mr. Arter. Then you’d pass First Baptist and Haywood’s, the only restaurant in town where Colored people could eat. You’d walk by four more houses before you got to our house. Four houses beyond us you’d run into St. James, where Church Street dead-ended at Barton. Crump Barbershop, where Daddy got his hair cut, was across the street from Haywood’s. Daddy’s mother lived in a little one-story house next door to Crump’s. Daddy kept a beautiful garden in her backyard, with rows of string beans, rhubarb, potatoes, onions, scallions, carrots, radishes, and beans. We ate from that garden during much of the year.

The Baptist and Methodist churches were the only ones that Colored people in White Sulphur could attend. Back then, each had a part-time preacher who would deliver service on two Sundays a month. The Methodist preacher preached on the first and third Sunday, the Baptist preacher on the second and fourth. Since most everyone went to church every week, that meant the Methodists attended the Baptist church and the Baptists attended the Methodist church on the weeks when their pastor wasn’t preaching. During the summer they held a combined picnic. They also combined their vacation Bible school, where children learned about the Bible during summer vacation.

St. Thomas Episcopal Church, where Reverend Eder presided, was on Main Street in the center of town. But only White people could attend. There was only one God, but segregation meant that White people and Colored people couldn’t worship Him in the same place. We let God be the judge of that.

Though people lived there all year long, White Sulphur Springs was a vacation town. Known as the “Queen of the Watering Places” in the South, it was where the well-heeled vacationers from Virginia’s coast and other Southern locations would escape summer’s heat and humidity. Because it was located two thousand feet high in the mountains, White Sulphur’s climate was much more comfortable than other southerly regions were.

Our town got its name from a freshwater mineral bath that bubbled up from deep underground. Before the European settlers arrived and killed off most of the indigenous people, Greenbrier County was part of the Can-tuc-kee territory, where the Shawnee and Cherokee peoples lived. According to legend, a young Shawnee couple slipped away to spend time alone. Their chief caught them together unsupervised, became angry, and shot two arrows toward them. The first killed the boy; the second whistled past the girl, pierced the ground, and supposedly created the springs. After the last drop of spring water has been drunk, the young woman’s suitor is supposed to return to life.

That’s the story according to legend. Scientifically, a thermal spring comes from geothermally heated groundwater rising from the Earth’s crust.

Regardless of the water’s source, for centuries people believed that it cured rheumatism’s stiff joints, as well as skin problems, respiratory illnesses, menstrual cramps, fevers, and so on. Folks would travel from across the South and beyond in order to visit the spring. Our town was also known for the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, a bloody conflict fought during the Civil War, where almost four hundred Union and Confederate soldiers were lost.

During the mid-1800s, an impressive six-story, snow-colored resort called the Greenbrier Hotel was built at the springs. Indeed, the Greenbrier looked so much like the White House that it was once known as “Old White.” Before the Civil War, five sitting presidents vacationed there, as did judges, lawyers, diplomats, slaveholders, and merchants—mostly from Southern states. Only two years before I was born, in 1916, President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson spent Easter at the Greenbrier. The grandparents of President John F. Kennedy, who wasn’t yet born, honeymooned there when I was two months old.

During the years right after my birth and well into the Roaring Twenties, the Greenbrier was very popular among the industrialists and other extremely wealthy people in American society. The C&O Railway owned the two-hundred-and-fifty-room property and delivered its guests—who, depending on the season, would vacation in places like the Greenbrier; Newport, Rhode Island; and Palm Beach, Florida—in their private coaches right to the resort’s front door. Indeed, the railroad stop was located right across Main Street from the resort. Passengers would step off the train and into a horse and carriage to be ridden across the road, their feet not even touching the ground. We townsfolk would gaze longingly at the visitors dressed so formally. The women would be attired in colorful ball gowns—blush pink, scarlet, sapphire blue, and forest green—and the men in tuxedos. From the outside, they seemed to live a wonderful life. The rest of us had to travel by foot, saddle up a horse, or maybe ride a horse and buggy to get around.

Daddy moved us into the town that developed around the Greenbrier, to make it easy for us to go to school. His sixth-grade education was not unusual. He had been born at a time when education was a luxury for Colored people, particularly in rural areas. Because they were often denied the opportunity to receive schooling around the turn of the twentieth century, when Daddy was born, about half of Colored people at that time were unable to read.

Because his own education had been prohibited, his children’s was extremely important to him. If there was one thing Daddy would say, it was that he didn’t want to raise any “dumb, ignorant children.” He was determined that his children would go to college.