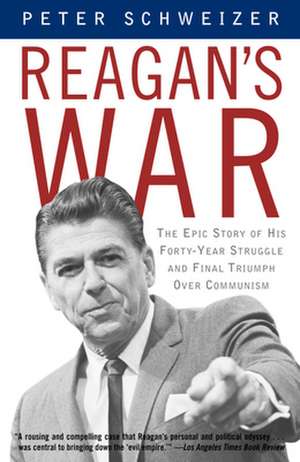

Reagan's War: The Epic Story of His Forty-Year Struggle and Final Triumph Over Communism

Autor Peter Schweizeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2003

Bringing to light previously secret information obtained from archives in the United States, Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Russia—including Reagan’s KGB file—Schweizer offers a compelling case that Reagan personally mapped out and directed his war against communism, often disagreeing with experts and advisers. An essential book for understanding the Cold War, Reagan’s War should be read by open-minded readers across the political spectrum.

Preț: 106.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 159

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.31€ • 22.07$ • 17.07£

20.31€ • 22.07$ • 17.07£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385722285

ISBN-10: 0385722281

Pagini: 372

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385722281

Pagini: 372

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Peter Schweizer is a fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace at Stanford University. His previous books include The Fall of the Wall: Reassessing the Causes and Consequences of the End of the Cold War, The Next War, coauthored with Casper Weinberger, Victory, and Friendly Spies. He lives in Florida with his wife and children.

Extras

chapter I

ONE-MAN BATTALION

Tall, tanned, and dark-haired, Ronald Reagan was often seen driving his Cadillac convertible on the open boulevards of Hollywood in late September 1946. He had been in pictures for almost ten years now. Superstardom had eluded him, but he was a star nonetheless. Only a few years earlier, a Gallup poll had ranked him with Laurence Olivier in terms of popularity among filmgoers.

Reagan knew that superstardom would probably never come, openly admitting to friends, "I'm no [Errol] Flynn or [Charles] Boyer." But life was comfortable. In August of 1945 he had signed a long-term, million-dollar contract with Warner Brothers. He was making more than $52,000 a picture and would take home the princely sum of $169,000 in 1946--and there were inviting projects on the horizon. Jack Warner, the pugnacious studio head, had offered him the lead in a film adaptation of John Van Druten's successful play The Voice of the Turtle. It was Reagan's first chance to play the romantic lead in a major A picture, and Warner was paying the playwright the unheard-of sum of $500,000 plus 15 percent of the gross for the story, so he clearly cared about the project. Reagan was also about to begin production on Night Unto Night, a dramatization of a successful Philip Wylie book.

In addition, Reagan had a wife and two little kids to go home to. Jane Wyman was a beautiful blonde from the Midwest whose own acting career was beginning to take off. Along with their children Michael and Maureen, Ron and Jane lived in a beautiful home with a pool on Cordell Drive. He owned a splendid ranch near Riverside, and when he and Jane weren't at the studio lot, they could be found playing golf at the prestigious Hillcrest Country Club with Jack Benny and George Burns. At night they often dined at the trendy Beverly Club.

It was without a doubt far more than the son of a salesman from Dixon, Illinois, had ever expected out of life. But on September 27, 1946, Reagan's celluloid dreamland would be disrupted forever.

In the early-morning hours, even before the sun peeked over the east hills, thousands of picketers showed up at Warner Brothers. They were vocal and angry. Hollywood had seen strikes before, but nothing quite like this.

The strike had been called by a ruddy-faced ex-boxer named Herb Sorrell, head of the Conference of Studio Unions (CSU), who was prepared to get rough. "There may be men hurt, there may be men killed before this is over, but we are in no mood to be pushed around anymore," he warned. For good measure, he had brought dozens of tough guys ("sluggers," he called them) in from San Francisco, just in case.

Herb Sorrell had come up the hard way, beginning work at the age of twelve, laboring in an Oakland sewer pipe factory for eleven hours a day. He had cut his teeth in the Bay Area labor movement under the leadership of Harry Bridges, the wiry leader of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union. Bridges, according to Soviet archives, was also a secret member of the Communist Party and a regular contact for Soviet intelligence.

Sorrell had joined the party in the 1930s, and under Bridges's guidance he had led two violent strikes in the Bay Area. Both strikes, he later admitted, were secretly funded by the Communists, and this time he was secretly receiving money from the National Executive Council of the Communist Party. Sorrell was a member of more than twenty Communist Party front organizations and had pushed hard for the American Federation of Labor to affiliate with the Soviet-run World Federation of Trade Unions. (AFL leaders refused on the grounds that it was simply a front group.2)

The studio strike Sorrell organized in 1946 was no ordinary labor action. It was ostensibly called because of worker concerns, but Sorrell saw it as an opportunity to gain control over all the major unions in Hollywood. As he bragged in the early days of the action, "When it ends up, there'll be only one man running labor in Hollywood, and that man will be me!"

The stakes were high. If Sorrell succeeded, the Communists believed, they could run Hollywood. As the party newspaper the People's Daily World put it candidly, "Hollywood is often called the land of Make-Believe, but there is nothing make believe about the Battle of Hollywood being waged today. In the front lines of this battle, at the studio gates, stand the thousands of locked out film workers; behind the studio gates sit the overlords of Hollywood, who refuse even to negotiate with the workers. . . . The prize will be the complete control of the greatest medium of communication in history." To underscore the value of this victory, the paper quoted Lenin: "Of all the arts, the cinema is the most important."

The Communist Party had been active in Hollywood since 1935, when a secret directive was issued by CPUSA (Communist Party of the U.S.A.) headquarters in New York calling for the capture of Hollywood's labor unions. The party believed that by doing so they could influence the type of pictures being produced. The directive also instructed party members to take leadership positions in the so-called intellectual groups in Hollywood, which were composed of directors, writers, and performers.

To carry out the plan, CPUSA sent party activist Stanley Lawrence, a tall, bespectacled ex-cabdriver. Quietly and methodically he began developing secret cells that included Hollywood performers, writers, and technicians. His actions were handled with great sensitivity. Lawrence reported directly to party headquarters in New York, which in turn reported its activities to officials in Moscow. There, Comintern boss Willie Muenzenberg declared, "One of the most pressing tasks confronting the Communist Party in the field of propaganda is the conquest of this supremely important propaganda unit, until now the monopoly of the ruling class. We must wrest it from them and turn it against them."

By the end of the Second World War, party membership in Hollywood was close to six hundred and boasted several industry heavyweights. Actors Lloyd Bridges, Edward G. Robinson, and Fredric March were members, as were half a dozen producers and about as many directors. Some had joined the party because they thought it might be fun. Actor Lionel Stander encouraged his friends to become members because "you will make out more with the dames." Others who were perhaps interested in the ideas of Marx and Lenin were nonetheless gentle in their advocacy.

"Please explain Marxism to me," Sam Goldwyn once asked Communist Ella Winter at a dinner party.

"Oh, not over this lovely steak."

But many of the party members were militants, and through hard work they had managed to take over leadership positions in the Screenwriters Guild, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), and various intellectual and cultural groups. Their level of control and influence far outweighed their numbers. It was a classic case of hard work and determined organizing.

"All over town the industrious Communist tail wagged the lazy liberal dog," declared director Philip Dunne, whose credits included Count of Monte Cristo, Last of the Mohicans, and Three Brave Men.

That industriousness came out of a militancy that stunned many in Hollywood. Screenwriter John Howard Lawson had a booming voice and could often be seen berating those who might oppose the party by smashing his fist into his open palm. The natural reaction of many was to simply be quiet and avoid being throttled.

"The important thing is that you should not argue with them," said writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, who spent time in Hollywood writing for movies such as Winter Carnival. "Whatever you say they have ways of twisting it into shapes which put you in some lower category of mankind, 'Fascist,' 'Liberal,' 'Trotskyist,' and disparage you both intellectually and personally in the process."

Reagan had his first taste of this a few months before the strike, when he was serving on the executive committee of the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of Arts, Sciences, and Professions (HICCASP), which he had joined in 1944. The group boasted a membership roll including Frank Sinatra, Orson Welles, and Katharine Hepburn. It was what they called a "brainy group," too, with Albert Einstein and Max Weber lending their name to the organization. It was the usual liberal/left Hollywood cultural group, concerned about atomic weapons, the resurgence of fascism, and the burgeoning Cold War. But some were concerned by what they saw as its regular and consistent support for the Soviet position on international issues. Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. declared in Life magazine that he believed it was a communist front, an organization in which "its celebrities maintained their membership but not their vigilance."

Stung by this criticism, a small group within HICCASP, including RKO executive Dore Schary, actress Olivia de Havilland, and FDR's son James Roosevelt, decided to put their fellow members to the test. At the July 2, 1946, meeting, Roosevelt noted that HICCASP had many times issued statements denouncing fascism. Why not issue a statement repudiating communism? Surely that would demonstrate that the organization was wholly liberal and not at all communist.

Reagan rose quickly and offered his support for the resolution, and a furious verbal battle quickly erupted. Musician Artie Shaw stood up and declared that the Soviet Union was more democratic than the United States and offered to recite the Soviet constitution to prove it. Writer Dalton Trumbo stood up and denounced the resolution as wicked. When Reagan tried to respond, John Howard Lawson waved a menacing finger in his face and told him to watch it. Reagan and the others in his group resigned from the organization.

Sorrell gathered his resources for the fight. Along with financial support from the Communist Party, he also could count on help from Vincente Lombardo Toledano, head of Mexico's largest union and described in Soviet intelligence files as an agent. The slender, well-dressed, and poised young lawyer was one of Moscow's most trusted agents in Mexico, regularly given assignments by Lt. General Pavel Fitin of Soviet intelligence. Toledano immediately put his resources behind Sorrell, providing money while pressuring Mexican film industry executives not to process any film from Hollywood as a show of solidarity. He also appeared at a rally in Hollywood to encourage the strikers.

Herb Sorrell had promised violence if he didn't get his way in the studio strike, and it didn't take him long to deliver. Led by his "sluggers," strikers smashed windshields on passing trains and threw rocks at the police. One studio employee went to the hospital after acid was thrown in his face. When the police tried to break up the melee, things got even worse. As actor Kirk Douglas remembered it, "Thousands of people fought in the middle of the street with knives, clubs, battery cables, brass knuckles, and chains."

Sorrell and his allies wanted to shut down the studios entirely, so anyone who crossed the picket line became a target of violence. Jack Warner insisted on keeping up production and the studio remained open. To avoid injury, workers, including stars who were shooting movies, were forced to sneak into the studio lot through a storm drain that led from the Los Angeles River.

Reagan, getting ready to start production on Night Unto Night, was furious about the violence. And unlike his approach to the little battle with the Communists in HICCASP, he was not in a mood to retreat.

Blaney Matthews, the giant-sized head of security at Warner Brothers, had seen this sort of violent strike before. He advised Reagan and other stars to use the storm drain to get onto the lot safely. Reagan flat out refused. If he was going to cross the picket line, he was going to cross the picket line, he told Matthews.

Matthews then arranged for buses to shuttle Reagan and a few others through the human gauntlet outside the studio gate. But he offered a bit of advice: Lie down on the floor, or you might get hit by a flying Coke bottle or rock. Again Reagan refused. Over the next several days, as he went to the studio lot to attend preproduction meetings, a bus would pass through the human throng of violent picketers, with a solitary figure seated upright inside.

Reagan was no doubt acting on his convictions and his determination not to be intimidated by the strikers. But he may also have seen it as an opportunity to demonstrate his courage. He had missed the action in the Second World War only a few years earlier. When he had reported for duty at Fort Mason in 1942, his medical exam had revealed poor eyesight.

"If we sent you overseas, you'd shoot a general," one doctor had told him.

"Yes," said the other. "And you'd miss him."

So instead of going off to war and serving bravely in the Army Air Corps like his friend Jimmy Stewart, Reagan was consigned to service in the First Motion Picture Unit, based just outside of Los Angeles.

Not bowing to violence was Reagan's first act of defiance. Another came when Sorrell tried to get the Screen Actors Guild to fall into line and support the strike. Reagan was a SAG board member, having joined with his wife's help in 1937. (Jane Wyman was already on the board.)

SAG had a quick vote after the strike began and elected to cross the picket line. But there were Sorrell supporters and Communist Party members among the SAG leadership, and they suggested that the guild try to arbitrate some kind of solution. A small group was asked to handle the matter. Reagan was among them.

By taking the assignment, Reagan was stepping foursquare into the middle of a testy labor dispute. It was the sort of thing he had been warned against before. Spencer Tracy had always advised his fellow actors to steer clear of politics. It was bad for your career and could get you into trouble, Tracy said. "Remember who shot Lincoln," he told them.

But Reagan, along with Gene Kelly and Katharine Hepburn, stepped into the breach. They met with labor officials and even with Sorrell himself. Matters were at an impasse.

Filming began on Night Unto Night at a dreary beach house just up the coast from Hollywood. Reagan was the lead in a story about a widow who believed her dead husband was communicating with her. The picture costarred Viveca Lindfors, an accomplished stage actress from Sweden.

After one take of a beach scene, Reagan was summoned to the telephone. When he picked up the receiver, a voice he didn't recognize threatened to see to it that he never made films again. If he continued to oppose the CSU strike, the caller said, "a squad" would disfigure his face with acid.

It was the first of many threats as the CSU and their Communist Party allies grew desperate to force SAG into line. Reagan hired guards to watch his kids. "I have been looking over my shoulder when I go down the street," he told a SAG meeting.

From the Hardcover edition.

ONE-MAN BATTALION

Tall, tanned, and dark-haired, Ronald Reagan was often seen driving his Cadillac convertible on the open boulevards of Hollywood in late September 1946. He had been in pictures for almost ten years now. Superstardom had eluded him, but he was a star nonetheless. Only a few years earlier, a Gallup poll had ranked him with Laurence Olivier in terms of popularity among filmgoers.

Reagan knew that superstardom would probably never come, openly admitting to friends, "I'm no [Errol] Flynn or [Charles] Boyer." But life was comfortable. In August of 1945 he had signed a long-term, million-dollar contract with Warner Brothers. He was making more than $52,000 a picture and would take home the princely sum of $169,000 in 1946--and there were inviting projects on the horizon. Jack Warner, the pugnacious studio head, had offered him the lead in a film adaptation of John Van Druten's successful play The Voice of the Turtle. It was Reagan's first chance to play the romantic lead in a major A picture, and Warner was paying the playwright the unheard-of sum of $500,000 plus 15 percent of the gross for the story, so he clearly cared about the project. Reagan was also about to begin production on Night Unto Night, a dramatization of a successful Philip Wylie book.

In addition, Reagan had a wife and two little kids to go home to. Jane Wyman was a beautiful blonde from the Midwest whose own acting career was beginning to take off. Along with their children Michael and Maureen, Ron and Jane lived in a beautiful home with a pool on Cordell Drive. He owned a splendid ranch near Riverside, and when he and Jane weren't at the studio lot, they could be found playing golf at the prestigious Hillcrest Country Club with Jack Benny and George Burns. At night they often dined at the trendy Beverly Club.

It was without a doubt far more than the son of a salesman from Dixon, Illinois, had ever expected out of life. But on September 27, 1946, Reagan's celluloid dreamland would be disrupted forever.

In the early-morning hours, even before the sun peeked over the east hills, thousands of picketers showed up at Warner Brothers. They were vocal and angry. Hollywood had seen strikes before, but nothing quite like this.

The strike had been called by a ruddy-faced ex-boxer named Herb Sorrell, head of the Conference of Studio Unions (CSU), who was prepared to get rough. "There may be men hurt, there may be men killed before this is over, but we are in no mood to be pushed around anymore," he warned. For good measure, he had brought dozens of tough guys ("sluggers," he called them) in from San Francisco, just in case.

Herb Sorrell had come up the hard way, beginning work at the age of twelve, laboring in an Oakland sewer pipe factory for eleven hours a day. He had cut his teeth in the Bay Area labor movement under the leadership of Harry Bridges, the wiry leader of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union. Bridges, according to Soviet archives, was also a secret member of the Communist Party and a regular contact for Soviet intelligence.

Sorrell had joined the party in the 1930s, and under Bridges's guidance he had led two violent strikes in the Bay Area. Both strikes, he later admitted, were secretly funded by the Communists, and this time he was secretly receiving money from the National Executive Council of the Communist Party. Sorrell was a member of more than twenty Communist Party front organizations and had pushed hard for the American Federation of Labor to affiliate with the Soviet-run World Federation of Trade Unions. (AFL leaders refused on the grounds that it was simply a front group.2)

The studio strike Sorrell organized in 1946 was no ordinary labor action. It was ostensibly called because of worker concerns, but Sorrell saw it as an opportunity to gain control over all the major unions in Hollywood. As he bragged in the early days of the action, "When it ends up, there'll be only one man running labor in Hollywood, and that man will be me!"

The stakes were high. If Sorrell succeeded, the Communists believed, they could run Hollywood. As the party newspaper the People's Daily World put it candidly, "Hollywood is often called the land of Make-Believe, but there is nothing make believe about the Battle of Hollywood being waged today. In the front lines of this battle, at the studio gates, stand the thousands of locked out film workers; behind the studio gates sit the overlords of Hollywood, who refuse even to negotiate with the workers. . . . The prize will be the complete control of the greatest medium of communication in history." To underscore the value of this victory, the paper quoted Lenin: "Of all the arts, the cinema is the most important."

The Communist Party had been active in Hollywood since 1935, when a secret directive was issued by CPUSA (Communist Party of the U.S.A.) headquarters in New York calling for the capture of Hollywood's labor unions. The party believed that by doing so they could influence the type of pictures being produced. The directive also instructed party members to take leadership positions in the so-called intellectual groups in Hollywood, which were composed of directors, writers, and performers.

To carry out the plan, CPUSA sent party activist Stanley Lawrence, a tall, bespectacled ex-cabdriver. Quietly and methodically he began developing secret cells that included Hollywood performers, writers, and technicians. His actions were handled with great sensitivity. Lawrence reported directly to party headquarters in New York, which in turn reported its activities to officials in Moscow. There, Comintern boss Willie Muenzenberg declared, "One of the most pressing tasks confronting the Communist Party in the field of propaganda is the conquest of this supremely important propaganda unit, until now the monopoly of the ruling class. We must wrest it from them and turn it against them."

By the end of the Second World War, party membership in Hollywood was close to six hundred and boasted several industry heavyweights. Actors Lloyd Bridges, Edward G. Robinson, and Fredric March were members, as were half a dozen producers and about as many directors. Some had joined the party because they thought it might be fun. Actor Lionel Stander encouraged his friends to become members because "you will make out more with the dames." Others who were perhaps interested in the ideas of Marx and Lenin were nonetheless gentle in their advocacy.

"Please explain Marxism to me," Sam Goldwyn once asked Communist Ella Winter at a dinner party.

"Oh, not over this lovely steak."

But many of the party members were militants, and through hard work they had managed to take over leadership positions in the Screenwriters Guild, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), and various intellectual and cultural groups. Their level of control and influence far outweighed their numbers. It was a classic case of hard work and determined organizing.

"All over town the industrious Communist tail wagged the lazy liberal dog," declared director Philip Dunne, whose credits included Count of Monte Cristo, Last of the Mohicans, and Three Brave Men.

That industriousness came out of a militancy that stunned many in Hollywood. Screenwriter John Howard Lawson had a booming voice and could often be seen berating those who might oppose the party by smashing his fist into his open palm. The natural reaction of many was to simply be quiet and avoid being throttled.

"The important thing is that you should not argue with them," said writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, who spent time in Hollywood writing for movies such as Winter Carnival. "Whatever you say they have ways of twisting it into shapes which put you in some lower category of mankind, 'Fascist,' 'Liberal,' 'Trotskyist,' and disparage you both intellectually and personally in the process."

Reagan had his first taste of this a few months before the strike, when he was serving on the executive committee of the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of Arts, Sciences, and Professions (HICCASP), which he had joined in 1944. The group boasted a membership roll including Frank Sinatra, Orson Welles, and Katharine Hepburn. It was what they called a "brainy group," too, with Albert Einstein and Max Weber lending their name to the organization. It was the usual liberal/left Hollywood cultural group, concerned about atomic weapons, the resurgence of fascism, and the burgeoning Cold War. But some were concerned by what they saw as its regular and consistent support for the Soviet position on international issues. Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. declared in Life magazine that he believed it was a communist front, an organization in which "its celebrities maintained their membership but not their vigilance."

Stung by this criticism, a small group within HICCASP, including RKO executive Dore Schary, actress Olivia de Havilland, and FDR's son James Roosevelt, decided to put their fellow members to the test. At the July 2, 1946, meeting, Roosevelt noted that HICCASP had many times issued statements denouncing fascism. Why not issue a statement repudiating communism? Surely that would demonstrate that the organization was wholly liberal and not at all communist.

Reagan rose quickly and offered his support for the resolution, and a furious verbal battle quickly erupted. Musician Artie Shaw stood up and declared that the Soviet Union was more democratic than the United States and offered to recite the Soviet constitution to prove it. Writer Dalton Trumbo stood up and denounced the resolution as wicked. When Reagan tried to respond, John Howard Lawson waved a menacing finger in his face and told him to watch it. Reagan and the others in his group resigned from the organization.

Sorrell gathered his resources for the fight. Along with financial support from the Communist Party, he also could count on help from Vincente Lombardo Toledano, head of Mexico's largest union and described in Soviet intelligence files as an agent. The slender, well-dressed, and poised young lawyer was one of Moscow's most trusted agents in Mexico, regularly given assignments by Lt. General Pavel Fitin of Soviet intelligence. Toledano immediately put his resources behind Sorrell, providing money while pressuring Mexican film industry executives not to process any film from Hollywood as a show of solidarity. He also appeared at a rally in Hollywood to encourage the strikers.

Herb Sorrell had promised violence if he didn't get his way in the studio strike, and it didn't take him long to deliver. Led by his "sluggers," strikers smashed windshields on passing trains and threw rocks at the police. One studio employee went to the hospital after acid was thrown in his face. When the police tried to break up the melee, things got even worse. As actor Kirk Douglas remembered it, "Thousands of people fought in the middle of the street with knives, clubs, battery cables, brass knuckles, and chains."

Sorrell and his allies wanted to shut down the studios entirely, so anyone who crossed the picket line became a target of violence. Jack Warner insisted on keeping up production and the studio remained open. To avoid injury, workers, including stars who were shooting movies, were forced to sneak into the studio lot through a storm drain that led from the Los Angeles River.

Reagan, getting ready to start production on Night Unto Night, was furious about the violence. And unlike his approach to the little battle with the Communists in HICCASP, he was not in a mood to retreat.

Blaney Matthews, the giant-sized head of security at Warner Brothers, had seen this sort of violent strike before. He advised Reagan and other stars to use the storm drain to get onto the lot safely. Reagan flat out refused. If he was going to cross the picket line, he was going to cross the picket line, he told Matthews.

Matthews then arranged for buses to shuttle Reagan and a few others through the human gauntlet outside the studio gate. But he offered a bit of advice: Lie down on the floor, or you might get hit by a flying Coke bottle or rock. Again Reagan refused. Over the next several days, as he went to the studio lot to attend preproduction meetings, a bus would pass through the human throng of violent picketers, with a solitary figure seated upright inside.

Reagan was no doubt acting on his convictions and his determination not to be intimidated by the strikers. But he may also have seen it as an opportunity to demonstrate his courage. He had missed the action in the Second World War only a few years earlier. When he had reported for duty at Fort Mason in 1942, his medical exam had revealed poor eyesight.

"If we sent you overseas, you'd shoot a general," one doctor had told him.

"Yes," said the other. "And you'd miss him."

So instead of going off to war and serving bravely in the Army Air Corps like his friend Jimmy Stewart, Reagan was consigned to service in the First Motion Picture Unit, based just outside of Los Angeles.

Not bowing to violence was Reagan's first act of defiance. Another came when Sorrell tried to get the Screen Actors Guild to fall into line and support the strike. Reagan was a SAG board member, having joined with his wife's help in 1937. (Jane Wyman was already on the board.)

SAG had a quick vote after the strike began and elected to cross the picket line. But there were Sorrell supporters and Communist Party members among the SAG leadership, and they suggested that the guild try to arbitrate some kind of solution. A small group was asked to handle the matter. Reagan was among them.

By taking the assignment, Reagan was stepping foursquare into the middle of a testy labor dispute. It was the sort of thing he had been warned against before. Spencer Tracy had always advised his fellow actors to steer clear of politics. It was bad for your career and could get you into trouble, Tracy said. "Remember who shot Lincoln," he told them.

But Reagan, along with Gene Kelly and Katharine Hepburn, stepped into the breach. They met with labor officials and even with Sorrell himself. Matters were at an impasse.

Filming began on Night Unto Night at a dreary beach house just up the coast from Hollywood. Reagan was the lead in a story about a widow who believed her dead husband was communicating with her. The picture costarred Viveca Lindfors, an accomplished stage actress from Sweden.

After one take of a beach scene, Reagan was summoned to the telephone. When he picked up the receiver, a voice he didn't recognize threatened to see to it that he never made films again. If he continued to oppose the CSU strike, the caller said, "a squad" would disfigure his face with acid.

It was the first of many threats as the CSU and their Communist Party allies grew desperate to force SAG into line. Reagan hired guards to watch his kids. "I have been looking over my shoulder when I go down the street," he told a SAG meeting.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A rousing and compelling case that Reagan's personal and political odyssey...was central to bringing down the 'evil empire.'" —Los Angeles Times Book Review

"On the big picture, Schweizer is correct: Reagan had it right." —Newsweek

"Masterful. . . . After Schweizer, even inveterate Reagan-haters will have to abandon the picture of an amiable dunce drifting passively while a handful of advisers set the agenda." —Foreign Affairs

“A fascinating, well-written, useful and important look at one of the three or four most important American political leaders of the 20th century. No serious assessment of the 40th president of the United States can ignore the central importance of anti-communism in his career; after Schweizer, none will.” —The Washington Post Book World

"On the big picture, Schweizer is correct: Reagan had it right." —Newsweek

"Masterful. . . . After Schweizer, even inveterate Reagan-haters will have to abandon the picture of an amiable dunce drifting passively while a handful of advisers set the agenda." —Foreign Affairs

“A fascinating, well-written, useful and important look at one of the three or four most important American political leaders of the 20th century. No serious assessment of the 40th president of the United States can ignore the central importance of anti-communism in his career; after Schweizer, none will.” —The Washington Post Book World

Descriere

In this meticulously researched analysis of the Cold War and the man who ended it, Schweizer delves into the origins of Ronald Reagan's vision of America, and documents his consistent, aggressive belief in confronting the Soviet Union diplomatically, economically, and militarily.