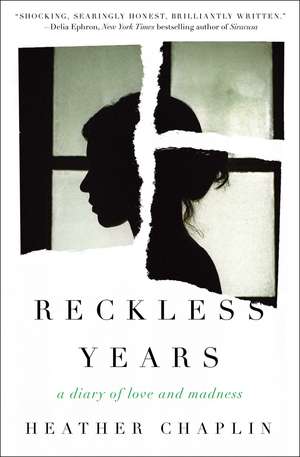

Reckless Years: A Diary of Love and Madness

Autor Heather Chaplinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 22 aug 2018

“What to do now, I don’t know. You see, I no longer love my husband.”

A thirty-something journalist living in Brooklyn, Heather Chaplin has to acknowledge the obvious: her marriage is over, and her career is stagnating. When she summons the courage to leave her husband behind, her life turns into an emotional roller coaster. She is soon dating a cast of characters in New York until an impulsive trip to Ireland thrusts her into the orb of a magnetic man named Kieran. But just when she believes herself to be on the brink of what she’d always wanted, a series of setbacks throw her into a volatile spiral downwards. Her independence becomes a frightening prison. As she struggles to find her way back to the world she once knew, she must confront the reality of the past to find her way to the possibilities of her future.

Narrated with a uniquely provocative voice, Reckless Years is a raw, propulsive debut: unfailingly profound and impossible to put down. Chaplin writes about all the things women aren’t supposed to say or feel: rage, manipulation, sexual desire—even madness. “Dramatic, adventurous, and heartbreaking” (Kirkus Reviews), yet ultimately redemptive, it is the story of losing yourself in the middle of a comeback and finding yourself in the most surprising of places.

Preț: 88.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.89€ • 18.35$ • 14.20£

16.89€ • 18.35$ • 14.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501135002

ISBN-10: 1501135007

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501135007

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Heather Chaplin is a writer living in Brooklyn. She’s written about all kinds of things in her journalism career and is the founding director of the Journalism + Design program at The New School. In the evenings, she can be found taking ballet classes she has no business attending but does anyway. Reckless Years is her second book.

Extras

Reckless Years

Monday, April 3, 2006

1:33 p.m.

What to do now, I don’t know. You see, I no longer love my husband.

It’s one of those New York spring afternoons when, as if overnight, the slush is gone and the blustery wind has ceased. Hyacinths, daffodils, and crocuses splash the ground with color, and the magnolia trees are just beginning to unfurl their fleshy blossoms. It’s one of those days when you simply have to be outside. But I’m not outside. I’m inside, my dog, Sakura, sitting like a sphinx on the floor at my feet. I’m on my couch in the back of our apartment, watching the spring day through my windows, smoking a spliff, listening to Coldplay (don’t even start with me about the Coldplay), and trying to figure out how I’m going to get out of this situation.

I had that dream again last night—the one where my father and Josh are chasing me. I can feel their breath on my neck, and I’m trying to scream, but no sound comes out. Bluegrass music plays. Then we’re all in the air, flying, cruising over an enormous crater in the earth, and I realize something terrible is happening beneath me. And then I’m falling, plummeting downward 100 miles an hour toward the terror, and trying, desperately, to cry out, please, someone, save me—but no one does.

I used to have this exact dream except instead of trying to get me, Josh was trying to help me. Sometimes when we fight, Josh still shouts at me about this dream.

How did this happen? How can it be that one day you’re so in love with a person that just being near him is like bathing in golden light, and then the next thing you know, you’re fantasizing he gets in a car accident or contracts a disease that doesn’t require any nursing and kills him quickly?

I’ve always believed that the really great writers are generous to their characters. But I warn you: I don’t feel generous toward Josh. I’ll have to throw myself on your mercy and say, forgive me, I’ve lived with the man for thirteen years. I have no generosity left.

At this moment, as I write this, my husband is sitting on the couch at the other end of our apartment watching the Golf Channel and sucking on a can of Coke. Sometimes I think Josh tries to stay as still as possible, hoping against hope that one day life will, at last, just leave him the fuck alone. What he doesn’t know is that I too may leave him alone.

Or maybe he does. He’s a crafty bastard beneath that gentle stoner demeanor.

I don’t know why I’m putting all this down on paper. I’m writing God knows what for God knows whom. I feel somehow that if I don’t write everything down, I will simply come flying apart. The center cannot hold! But maybe, just maybe, if I document every single thing I see, hear, and feel, I can keep it together, spinning a web of words around myself that will keep me from breaking apart from the inside out.

I’ve been doing this since I was a kid, really, writing everything down, even tracing words on my forefinger with my thumb like a tic—trying to make sense, I suppose, through the calming logic of language, of a world that is simply too chaotic and too mad to make sense of.

For the record, I was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in Sinai Hospital, not one mile from the Preakness racetrack. My mother was a German-Jewish immigrant from South Africa. She grew up in a prefabricated house in New Haven, Connecticut, with her mother, sister, and grandparents. She never knew why the older generation spoke German—Holocaust, what Holocaust?—and she never knew why they left South Africa for America without her father. (He had a child with another woman.) She knew she never saw her father again and that she couldn’t move the left side of her body very well because of a childhood bout with encephalitis. From pictures, I know that my mother was slim and lovely with violet eyes, black eyelashes, and an impossibly small waist, like a young Elizabeth Taylor.

Anyway, the reason she ended up in the postindustrial, recession-ridden nightmare that was Baltimore in the 1970s with two small children and a quite possibly psychotic anarchist of a husband had something to do with bluegrass music and a strong desire at nineteen to escape that house in New Haven. Still, marrying my father was not her best move. Neither was having children, really. Can you imagine? It’s 1965, you marry some asshole you meet at a Country Gentlemen concert, you move to Baltimore, of all places, you have two kids, and then—bam! The sexual revolution hits. The women’s movement! Oh wait, I didn’t have to get married? I didn’t have to procreate?

My father was gone before I was one, and she hit the Baltimore nightlife with a vengeance. Baltimore was still a thriving seaport in those days, and she seemed far more interested in Greek sailors and disco dancing than keeping house and raising children. In the afternoons, my brother, Seth, and I used to play we were in Vietnam as we fought our way through the fruit flies that infested our kitchen. At night we heard laughter and stumbling on the stairs and ran into men who didn’t speak English in the bathroom. What can I say? It was the seventies. My mother had a life she wanted to live. And who can blame her, really? Well, me for many years, until I got older and fucked up my own life.

My father, I’ll give you the basics. He grew up in a tiny apartment in the Bronx, his father a Russian-Jewish immigrant. My grandfather—Zaidie, we called him—was the kind of guy who when you telephoned said, “Oh, it’s you, how come you never call?” And when you asked him what he was doing, said, “Oh, just sitting here in the dark.” Photographs of that side of my family show people with faces so dark and stormy it’s as if they’re perpetually standing in shadows.

My dad hit Bronx Science at ten and Johns Hopkins at fifteen. Graduated: never. He was a first-generation computer programmer who didn’t believe in the twenty-four-hour day, a smuggler for the Sandinistas, and a professional mandolin player. He thought 1968 was the high-water mark of human civilization, and he was waiting for the day when humans shared a single consciousness and boundaries of all kinds disappeared. When I was a kid, I said that sounded terrifying, but he said that was just because I had petty bourgeois values. He took my brother and me to New York with him and left us under blankets in the back of his van in the middle of the night while he dropped off computers for the Nicaraguans. He took us to Florida for vacation and drove 100 miles an hour the whole way because we were running late—me sitting in the passenger seat, afraid to close my eyes, sure that if I did, even for a minute, I would be killed.

I officially cut off contact with my father fifteen years ago. I’ve seen him once since. I was arrested covering an International Monetary Fund protest in DC, and, while hog-tied in a police gymnasium, I heard my name called out and found that someone—someone with the exact name of my father—had bailed me out. Who knew, but he’d been in DC protesting the International Monetary Fund. I hadn’t seen him in all those years, and there he was waiting for me outside the jail, proud as if I’d provided him with a grandchild. No words of reproach for the years of silence. No apologies. No requests for apologies. It was like he didn’t remember that I’d cut off contact. Or why. Just, “In times like these, Heather, getting arrested is a badge of honor.” I was so stunned by his physical presence, I forgot that I’d sworn never to let him near me again. I actually got in his van with him. And then he nearly killed me by falling asleep while driving us back to the Washington Monument.

Why am I telling you all this? I don’t even know who you are. You’re the person I’ve been writing to all my life, I suppose—you’re someone who cares about me, whose attention I have a right to claim. In other words, you’re nobody at all. And perhaps that’s what feels so good about this. I can write anything here, because it isn’t for anyone. I can say whatever I want and suffer no consequences.

Yes, this is my life right now—a lovely day of streaming spring light and blossoming spring flowers. And me sitting here on my little couch, mouthing the words I’ve tried so long to avoid. I no longer love my husband. I don’t want to be his wife.

Monday, April 3, 2006

1:33 p.m.

What to do now, I don’t know. You see, I no longer love my husband.

It’s one of those New York spring afternoons when, as if overnight, the slush is gone and the blustery wind has ceased. Hyacinths, daffodils, and crocuses splash the ground with color, and the magnolia trees are just beginning to unfurl their fleshy blossoms. It’s one of those days when you simply have to be outside. But I’m not outside. I’m inside, my dog, Sakura, sitting like a sphinx on the floor at my feet. I’m on my couch in the back of our apartment, watching the spring day through my windows, smoking a spliff, listening to Coldplay (don’t even start with me about the Coldplay), and trying to figure out how I’m going to get out of this situation.

I had that dream again last night—the one where my father and Josh are chasing me. I can feel their breath on my neck, and I’m trying to scream, but no sound comes out. Bluegrass music plays. Then we’re all in the air, flying, cruising over an enormous crater in the earth, and I realize something terrible is happening beneath me. And then I’m falling, plummeting downward 100 miles an hour toward the terror, and trying, desperately, to cry out, please, someone, save me—but no one does.

I used to have this exact dream except instead of trying to get me, Josh was trying to help me. Sometimes when we fight, Josh still shouts at me about this dream.

How did this happen? How can it be that one day you’re so in love with a person that just being near him is like bathing in golden light, and then the next thing you know, you’re fantasizing he gets in a car accident or contracts a disease that doesn’t require any nursing and kills him quickly?

I’ve always believed that the really great writers are generous to their characters. But I warn you: I don’t feel generous toward Josh. I’ll have to throw myself on your mercy and say, forgive me, I’ve lived with the man for thirteen years. I have no generosity left.

At this moment, as I write this, my husband is sitting on the couch at the other end of our apartment watching the Golf Channel and sucking on a can of Coke. Sometimes I think Josh tries to stay as still as possible, hoping against hope that one day life will, at last, just leave him the fuck alone. What he doesn’t know is that I too may leave him alone.

Or maybe he does. He’s a crafty bastard beneath that gentle stoner demeanor.

I don’t know why I’m putting all this down on paper. I’m writing God knows what for God knows whom. I feel somehow that if I don’t write everything down, I will simply come flying apart. The center cannot hold! But maybe, just maybe, if I document every single thing I see, hear, and feel, I can keep it together, spinning a web of words around myself that will keep me from breaking apart from the inside out.

I’ve been doing this since I was a kid, really, writing everything down, even tracing words on my forefinger with my thumb like a tic—trying to make sense, I suppose, through the calming logic of language, of a world that is simply too chaotic and too mad to make sense of.

For the record, I was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in Sinai Hospital, not one mile from the Preakness racetrack. My mother was a German-Jewish immigrant from South Africa. She grew up in a prefabricated house in New Haven, Connecticut, with her mother, sister, and grandparents. She never knew why the older generation spoke German—Holocaust, what Holocaust?—and she never knew why they left South Africa for America without her father. (He had a child with another woman.) She knew she never saw her father again and that she couldn’t move the left side of her body very well because of a childhood bout with encephalitis. From pictures, I know that my mother was slim and lovely with violet eyes, black eyelashes, and an impossibly small waist, like a young Elizabeth Taylor.

Anyway, the reason she ended up in the postindustrial, recession-ridden nightmare that was Baltimore in the 1970s with two small children and a quite possibly psychotic anarchist of a husband had something to do with bluegrass music and a strong desire at nineteen to escape that house in New Haven. Still, marrying my father was not her best move. Neither was having children, really. Can you imagine? It’s 1965, you marry some asshole you meet at a Country Gentlemen concert, you move to Baltimore, of all places, you have two kids, and then—bam! The sexual revolution hits. The women’s movement! Oh wait, I didn’t have to get married? I didn’t have to procreate?

My father was gone before I was one, and she hit the Baltimore nightlife with a vengeance. Baltimore was still a thriving seaport in those days, and she seemed far more interested in Greek sailors and disco dancing than keeping house and raising children. In the afternoons, my brother, Seth, and I used to play we were in Vietnam as we fought our way through the fruit flies that infested our kitchen. At night we heard laughter and stumbling on the stairs and ran into men who didn’t speak English in the bathroom. What can I say? It was the seventies. My mother had a life she wanted to live. And who can blame her, really? Well, me for many years, until I got older and fucked up my own life.

My father, I’ll give you the basics. He grew up in a tiny apartment in the Bronx, his father a Russian-Jewish immigrant. My grandfather—Zaidie, we called him—was the kind of guy who when you telephoned said, “Oh, it’s you, how come you never call?” And when you asked him what he was doing, said, “Oh, just sitting here in the dark.” Photographs of that side of my family show people with faces so dark and stormy it’s as if they’re perpetually standing in shadows.

My dad hit Bronx Science at ten and Johns Hopkins at fifteen. Graduated: never. He was a first-generation computer programmer who didn’t believe in the twenty-four-hour day, a smuggler for the Sandinistas, and a professional mandolin player. He thought 1968 was the high-water mark of human civilization, and he was waiting for the day when humans shared a single consciousness and boundaries of all kinds disappeared. When I was a kid, I said that sounded terrifying, but he said that was just because I had petty bourgeois values. He took my brother and me to New York with him and left us under blankets in the back of his van in the middle of the night while he dropped off computers for the Nicaraguans. He took us to Florida for vacation and drove 100 miles an hour the whole way because we were running late—me sitting in the passenger seat, afraid to close my eyes, sure that if I did, even for a minute, I would be killed.

I officially cut off contact with my father fifteen years ago. I’ve seen him once since. I was arrested covering an International Monetary Fund protest in DC, and, while hog-tied in a police gymnasium, I heard my name called out and found that someone—someone with the exact name of my father—had bailed me out. Who knew, but he’d been in DC protesting the International Monetary Fund. I hadn’t seen him in all those years, and there he was waiting for me outside the jail, proud as if I’d provided him with a grandchild. No words of reproach for the years of silence. No apologies. No requests for apologies. It was like he didn’t remember that I’d cut off contact. Or why. Just, “In times like these, Heather, getting arrested is a badge of honor.” I was so stunned by his physical presence, I forgot that I’d sworn never to let him near me again. I actually got in his van with him. And then he nearly killed me by falling asleep while driving us back to the Washington Monument.

Why am I telling you all this? I don’t even know who you are. You’re the person I’ve been writing to all my life, I suppose—you’re someone who cares about me, whose attention I have a right to claim. In other words, you’re nobody at all. And perhaps that’s what feels so good about this. I can write anything here, because it isn’t for anyone. I can say whatever I want and suffer no consequences.

Yes, this is my life right now—a lovely day of streaming spring light and blossoming spring flowers. And me sitting here on my little couch, mouthing the words I’ve tried so long to avoid. I no longer love my husband. I don’t want to be his wife.

Recenzii

“Shocking, searingly honest, disturbing, brilliantly written. Reading this memoir is like being in a car speeding into an explosion and miraculously coming out the other side. Thank God. It would be awful if a writer this talented hadn’t made it.”

—Delia Ephron, author of SIRACUSA

"Reckless Years is a stunningly forensic account of the end of a marriage and its aftermath, which combines the honesty of memoir with the urgency of good fiction and a dry wit that, for all the darkness of the story, makes Chaplin a joy to spend time with."

—Emma Brockes, author of SHE LEFT ME THE GUN

“Chaplin’s epistolary memoir, extracted from two years of recovered emails and journals she’d kept beginning in 2006, chronicles the dramatic, adventurous, and heartbreaking story of a restless married woman who’d fallen out of love with her husband of 13 years…[A] satisfying memoir that will appeal most to women who’ve found themselves fleeing hopeless relationships.”

--Kirkus Reviews

—Delia Ephron, author of SIRACUSA

"Reckless Years is a stunningly forensic account of the end of a marriage and its aftermath, which combines the honesty of memoir with the urgency of good fiction and a dry wit that, for all the darkness of the story, makes Chaplin a joy to spend time with."

—Emma Brockes, author of SHE LEFT ME THE GUN

“Chaplin’s epistolary memoir, extracted from two years of recovered emails and journals she’d kept beginning in 2006, chronicles the dramatic, adventurous, and heartbreaking story of a restless married woman who’d fallen out of love with her husband of 13 years…[A] satisfying memoir that will appeal most to women who’ve found themselves fleeing hopeless relationships.”

--Kirkus Reviews