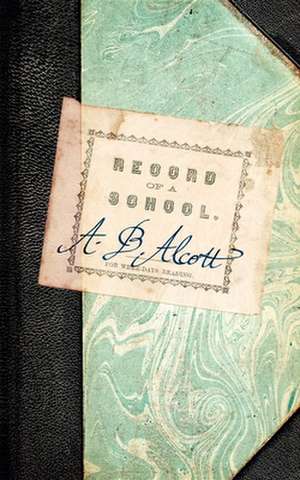

As you read Elizabeth Peabody's Record of a School, imagine that you are seated on a green velvet couch under a cathedral window that takes up much of an entire wall of the most unusual classroom you have ever seen. You have just walked across the tree-lined Boston Common and climbed a flight of stairs leading to an airy loft space that fills the upper story of Boston's new Masonic Temple on Tremont Street, a Gothic Revival structure considered "one of the chief architectural ornaments of the city." There you find roughly two-dozen children, boys and girls aged five to fifteen, busily occupied at work stations arranged through the sixty-foot-long schoolroom. Some are studying quietly at desks lining one wall, others are refreshing themselves at a "table of sense," where a pitcher of water awaits any thirsty scholar. But most are seated in chairs arrayed in a semi-circle in front of the teacher's own u-shaped desk, custom-designed so that his pupils can imagine he is always available to them, engaged in an intense discussion. All of this is new to you, and would be to anyone else in this time and place: Boston, 1835. Work stations, water table, chairs arranged in anything other than straight rows. But newest of all is the notion of teacher and pupils conversing. This is what you have come to see and hear. In all the schools you know, particularly those for boys, lecture and recitation is the order of the day, discipline with the rod the only sure guarantee that students will pay attention and learn their lessons. Yet in this classroom, with no rod in evidence, the children attend to their teacher's every word. And then, more astonishing, the small pupils utter their own thoughts in response. Clever, insightful, eloquent; hesitant, childish, or prosaic-no matter, each student's remarks are received with sincere interest by the ebullient, rangy figure seated behind the u-shaped desk, a blue-eyed blond-haired man named Bronson Alcott. Indeed, at times it seems as if this open-hearted teacher has permitted the children themselves to lead the discussion. Simply by virtue of the curiosity that has brought you to the visitors' couch at Bronson Alcott's Temple School, you are a member of a small but influential band of New England freethinkers dedicated to "the newness": men and women, as Alcott's partner and promoter, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, would write, "who have dared to say to one another . . . Why not begin to move the mountain of custom and convention?" You might be joined by other seekers after innovation-the British journalist Harriet Martineau, for example, who would describe the school in her 1837 travelogue Society in America. There she summarized Bronson Alcott's unorthodox methods, his belief that "his little pupils possessed . . . all truth, in philosophy and morals," and his view that it was "his business . . . to bring it out into expression; to help the outward life to conform to the inner light." Or you might find yourself seated next to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who visited the Temple School with his bride Lidian. When Elizabeth Peabody sent Emerson her draft of Record of a School, he wrote that he'd read it "with greatest pleasure" and hoped that "it may be printed speedily" so that its usefulness could be tested. The finished book, he said, was "beautiful . . . certain true & pleasant." It read like a novel. But at this particular historical moment, Emerson's word counts for little beyond a small circle of admirers in Boston and nearby Concord. He has delivered only one complete series of public lectures, downstairs in the main hall of this same Masonic Temple, and he has published nothing. On this day, Bronson Alcott seems to hold just as much promise, and he is the man you have come to see in action, invited by one of Boston's most prominent women of letters, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. * "Alcott is a man destined . . . to make an era in society, and I believe he will," Elizabeth Peabody wrote in July, 1834, scarcely a month into her acquaintance with the thirty-four-year-old idealist. She had just read through the journals his students had written in an experimental school Alcott kept for a short time in Germantown, Pennsylvania, before moving to Boston with his wife Abigail and their two young daughters, Anna and Louisa May. Elizabeth Peabody found the children's writing skills, along with the self-inquiry they exhibited, remarkable. At thirty, Peabody was a teacher herself and a woman of prodigious learning-Alcott said she possessed "the most magnificent philosophic imagination" of any person he ever knew. She was also well-connected and ready to do anyone she admired a good turn. Peabody offered to help Alcott start a school in Boston where he could test his theories more effectively. She would even teach Latin and mathematics, subjects in which Alcott had no expertise, free of charge untiiiiiil Alcott began to make a profit. By September, 1834, just in time for the fall semester, Peabody had found Alcott his pupils and the classroom in the Masonic Temple. And she helped him furnish it, supplying her own green velvet couch for the visitors she hoped would broadcast the school's innovative methods to the world at large. Recording Alcott's dialogues with his pupils was Peabody's idea as well. Initially she did it for the students' benefit: she read the conversations out loud to them at the end of the school day so that they could review and consolidate their thoughts. But as Peabody saw Alcott's experiment begin to succeed, she became more ambitious for the pages she was rapidly accumulating. One small boy told her, "I never knew I had a mind till I came to this school." In the classroom dialogues, she boasted to her sister Mary, the children don't just talk, "they create." She decided to publish her record. Peabody added her own commentary to Alcott's dialogues, explaining the purpose of the school: to prove that the "innocence" of childhood was a "positive condition," one that "comprehends all the instincts and feelings which naturally tend to good, such as humility, self-forgetfulness, love, trust." In a young America, only beginning to shake off the constraints of a strict Calvinism which taught that children were born sinners, this was a radical agenda. Although they did not yet call themselves by this term, Peabody and Alcott were transcendentalists who subscribed to a romanticism that idealized childhood as offering wisdom for adults, rather than the other way around. Like Wordsworth, whose poetry they taught in the Temple School, Peabody and Alcott believed "the child is father to the man." Peabody's Record of a School would be the first book of transcendentalist ideas to be published in America. As Peabody and Alcott read over the proofs of the book during the summer of 1835, they felt a growing excitement. "How much life you can breathe into me from your sympathy in my pursuits and purposes," Alcott wrote Peabody in gratitude, "I know not that I have another to whom I can truly apply the name of friend as yourself." In return, Peabody praised Alcott's "genius for education," admitting, "I am vain enough to say, that you are the only one I ever saw who, I soberly thought, surpassed my gift in . . . the divinest of all arts." To Peabody, Alcott, Emerson, and their circle, education was a divine art. Peabody's mentor, the Boston minister Rev. William Ellery Channing, considered his preaching-which made him the most charismatic liberal theologian of his day-to be educating his flock. Emerson viewed his lectures the same way. Elizabeth Peabody's Record of a School should be read as the first in a long line of books that attempt to reform not just schools, but society as a whole, by considering the classroom a microcosm of the human community. Record of a School was nothing less than Peabody's account of the "unfolding" of the human spirit. It was written with the same evangelical fervor as the 1960s classic Summerhill, which spoke for a similar historical moment of intellectual ferment and social turmoil with its own record of an experimental school. The first edition of a thousand copies sold briskly during the fall of 1835 to Boston's intelligentsia-until a warehouse fire destroyed half that number. Peabody arranged for a second edition of Record of a School, with an expanded "Explanatory Preface," to be published early in 1836. By then the popular novelist Catharine Maria Sedgwick had given the book the lead review in the February issue of the New York magazine The Knickerbocker. Sedgwick noted, with some reservation, that "Mr. Alcott rejects all previous systems," and she complained of his "tendency to ultraism, to go beyond not only all customary and prescribed, but . . . all practicable limits." But she applauded his results: "Mr. Alcott has shown, how much more intelligent [children] are-how much more capable of thought, and reflection, and of moral and intellectual discrimination-than has been generally supposed." As for the recorder, Elizabeth Peabody: "She is evidently a woman of genius, and her remarks, when not too deeply spiritual . . . are very fine." Sedgwick was not partial to the "mystical" philosophy that underlay the Temple School experiment; but she was sympathetic to its liberation of its pupils from drudgery and harsh discipline. That Record of a School found this measure of acclaim in the mainstream New York press was remarkable; that news of this tiny free school on Boston Common reached England with Martineau's book a year later was astounding. Peabody herself sent the book to Wordsworth, completing the circle of influence. In September of 1835, as Record of a School went to press, enrollment in the Temple School for its second year was high, and Peabody and Alcott's hopes for continued success seemed justified. But just as quickly, it all melted away. Within the year, Alcott created a scandal by issuing his own second volume of classroom conversations, ignoring Peabody's advice to delete certain controversial passages that she knew would offend even the school's supporters. This was the beginning of the end of a fascinating story that can be read in most Alcott biographies and books about Peabody as well. By 1838, the school was shut down, and Alcott never taught children again. Peabody, more resourceful and less easily discouraged, took up a series of professions-bookseller, editor, publisher-before returning to the cause of education in the 1860s as founder of kindergartens in America. What remains of the Temple School experiment is a set of core beliefs that still appeal to progressive educators and enlightened parents today: a commitment to honor the spirit of childhood in the classroom; an expectation that the imagination can be "called into life" in school. Looking back on their work together, Peabody always maintained that Alcott's teaching contained "a current of the true method-an infusion of Truth." Read her Record of a School, and see if you think she's right.