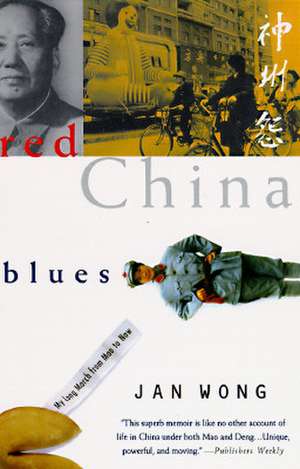

Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now

Autor Jan Wongen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 1997

Red China Blues is Wong's startling--and ironic--memoir of her rocky six-year romance with Maoism (which crumbled as she became aware of the harsh realities of Chinese communism); her dramatic firsthand account of the devastating Tiananmen Square uprising; and her engaging portrait of the individuals and events she covered as a correspondent in China during the tumultuous era of capitalist reform under Deng Xiaoping. In a frank, captivating, deeply personal narrative she relates the horrors that led to her disillusionment with the "worker's paradise." And through the stories of the people--an unhappy young woman who was sold into marriage, China's most famous dissident, a doctor who lengthens penises--Wong reveals long-hidden dimensions of the world's most populous nation.

In setting out to show readers in the Western world what life is like in China, and why we should care, she reacquaints herself with the old friends--and enemies of her radical past, and comes to terms with the legacy of her ancestral homeland.

Preț: 117.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 177

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.56€ • 23.41$ • 18.85£

22.56€ • 23.41$ • 18.85£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385482325

ISBN-10: 0385482329

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 141 x 209 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385482329

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 141 x 209 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Jan Wong was the Beijing correspondent for the Toronto Globe and Mail from 1988 to 1994. She is a graduate of McGill University and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and is the recipient of the George Polk Award, and other honors for her reporting. Wong has written for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, among many other publications in the United States and abroad. She lives in Toronto.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Ten days after my reprieve, Cadre Huang surprised us by announcing we were going to the Beijing Number One Machine Tool Factory for fifty days of labor. Erica and I let out a cheer. We had been lobbying for months for a chance at thought reform. For foreign students like us, hard labor was an honor. In my case in particular, it meant I was no longer persona non grata.

According to Mao, everyone needed physical labor. For class enemies, it was a punishment. For ordinary people, it was an inoculation against bourgeois thinking. For intellectuals, sweating with the proletariat was both a punishment and a prophylactic. In one year, Scarlet’s class had already been through mandatory stints of kaimen banxue, or open-door schooling, at a farm, a factory, a seaport and a military base.

The Number One Machine Tool Factory, which made lathes, was one of six model factories directly under the political control of Mao and his radical wife. In 1950, Mao had sent his eldest son there to work incognito as deputy Party secretary. In 1966, Number One was the factory considered politically reliable enough to send Workers Propaganda Teams into Beijing University.

Erica, our teachers and I shared one small room in a dingy workers’ dormitory. The toilet stalls down the hall were so disgusting I learned to breathe through my mouth. Each morning, we ignored the first, ear-splitting 5 a.m. bell and got up with the 6 a.m. one. We washed in groggy silence, then donned coarse work suits, stiff denim caps and canvas work gloves with seams so thick they gave me blisters. It was still dark when we stumbled outside to board a city bus for the fifteen-minute ride to the factory.

Number One, a sprawling collection of low-lying ugly brick buildings in southeast Beijing, was originally a munitions factory. The Chinese government saw to it that the proletariat lived better than intellectuals. As “workers,” we now could shower every day, instead of just twice a week. And unlike the slop served at the Big Canteen, the factory dining halls provided a wide selection of dumplings, noodles, breads and stir-fried dishes.

I was “apprenticed” to Master Liu, a fortyish man with a perpetually anxious look on his face, probably because he was supposed to teach me how to use a lathe. According to socialist etiquette, I called him Master Liu and he called me Little Wong. He had typical class-enemy looks — sallow skin, shifty eyes and a scrawny build — but in fact he was a kindly man with a mania for playing basketball. Under his influence, I joined the women’s team, where my towering five-foot, three-inch height was an asset.

In the middle of the first afternoon, Master Liu told me to start tidying up to get ready for a political meeting. Wiping the gunk off my hands with oily rags, I was beside myself with excitement; Beijing University had always barred me from political study. I joined about a dozen workers sitting in a circle on little folding stools. A middle-aged worker cleared his throat. “Today we are going to discuss with what attitude we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress. Please, everyone actively speak out.”

I looked around expectantly. Granted, it wasn’t the world’s sexiest topic, but what would the proletariat have to say? Nothing, it turned out. There was an awkward silence. Finally, a young worker in stained denim spoke up.

“Uh, uh, the proletariat, uh, um, the dictatorship of the proletariat, er, the proletariat is the leading class. It must lead everything.” He stopped, unsure of what to say next. He reddened slightly.

“Speak out,” said the middle-aged worker, nodding encouragingly.

“Uh, well, I think the way we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress is to, ah, um, study Marxism! Study Marxism-Leninism! Yes, to correctly receive the opening we must study Marxism-Leninism,” he said. He sat back, looking relieved. Others, all men, began to talk in monotones. Many stared at the patch of concrete floor in front of them. The first worker had set the tone. Each speaker exhorted everyone else to study Marxism-Leninism. Even I felt my eyes glazing over. When the discussion leader finally announced the meeting was over, people bolted for the door.

That first night, waiting in line in the canteen, I spotted a commotion ahead of me. Two young men had faced off, their noses inches apart.

“You turtle’s egg!” one of them screamed, using the ancient Chinese word for bastard.

“I fuck your mother’s cunt!” the other yelled back, using a more contemporary phrase.

At that, the motherfucker slapped the turtle’s egg, who responded by heaving a bowl of steaming dumplings in the other’s face. Someone threw a punch, and they began fighting in earnest until bystanders pulled them apart. I had a feeling my Chinese was going to take a great leap forward at the factory.

According to Mao, everyone needed physical labor. For class enemies, it was a punishment. For ordinary people, it was an inoculation against bourgeois thinking. For intellectuals, sweating with the proletariat was both a punishment and a prophylactic. In one year, Scarlet’s class had already been through mandatory stints of kaimen banxue, or open-door schooling, at a farm, a factory, a seaport and a military base.

The Number One Machine Tool Factory, which made lathes, was one of six model factories directly under the political control of Mao and his radical wife. In 1950, Mao had sent his eldest son there to work incognito as deputy Party secretary. In 1966, Number One was the factory considered politically reliable enough to send Workers Propaganda Teams into Beijing University.

Erica, our teachers and I shared one small room in a dingy workers’ dormitory. The toilet stalls down the hall were so disgusting I learned to breathe through my mouth. Each morning, we ignored the first, ear-splitting 5 a.m. bell and got up with the 6 a.m. one. We washed in groggy silence, then donned coarse work suits, stiff denim caps and canvas work gloves with seams so thick they gave me blisters. It was still dark when we stumbled outside to board a city bus for the fifteen-minute ride to the factory.

Number One, a sprawling collection of low-lying ugly brick buildings in southeast Beijing, was originally a munitions factory. The Chinese government saw to it that the proletariat lived better than intellectuals. As “workers,” we now could shower every day, instead of just twice a week. And unlike the slop served at the Big Canteen, the factory dining halls provided a wide selection of dumplings, noodles, breads and stir-fried dishes.

I was “apprenticed” to Master Liu, a fortyish man with a perpetually anxious look on his face, probably because he was supposed to teach me how to use a lathe. According to socialist etiquette, I called him Master Liu and he called me Little Wong. He had typical class-enemy looks — sallow skin, shifty eyes and a scrawny build — but in fact he was a kindly man with a mania for playing basketball. Under his influence, I joined the women’s team, where my towering five-foot, three-inch height was an asset.

In the middle of the first afternoon, Master Liu told me to start tidying up to get ready for a political meeting. Wiping the gunk off my hands with oily rags, I was beside myself with excitement; Beijing University had always barred me from political study. I joined about a dozen workers sitting in a circle on little folding stools. A middle-aged worker cleared his throat. “Today we are going to discuss with what attitude we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress. Please, everyone actively speak out.”

I looked around expectantly. Granted, it wasn’t the world’s sexiest topic, but what would the proletariat have to say? Nothing, it turned out. There was an awkward silence. Finally, a young worker in stained denim spoke up.

“Uh, uh, the proletariat, uh, um, the dictatorship of the proletariat, er, the proletariat is the leading class. It must lead everything.” He stopped, unsure of what to say next. He reddened slightly.

“Speak out,” said the middle-aged worker, nodding encouragingly.

“Uh, well, I think the way we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress is to, ah, um, study Marxism! Study Marxism-Leninism! Yes, to correctly receive the opening we must study Marxism-Leninism,” he said. He sat back, looking relieved. Others, all men, began to talk in monotones. Many stared at the patch of concrete floor in front of them. The first worker had set the tone. Each speaker exhorted everyone else to study Marxism-Leninism. Even I felt my eyes glazing over. When the discussion leader finally announced the meeting was over, people bolted for the door.

That first night, waiting in line in the canteen, I spotted a commotion ahead of me. Two young men had faced off, their noses inches apart.

“You turtle’s egg!” one of them screamed, using the ancient Chinese word for bastard.

“I fuck your mother’s cunt!” the other yelled back, using a more contemporary phrase.

At that, the motherfucker slapped the turtle’s egg, who responded by heaving a bowl of steaming dumplings in the other’s face. Someone threw a punch, and they began fighting in earnest until bystanders pulled them apart. I had a feeling my Chinese was going to take a great leap forward at the factory.

Recenzii

"A marvellous book by one of Canada’s best-ever foreign correspondents at the top of her form." - The Gazette (Montreal)

"Totally captivating. A wonderful memoir." - The Globe and Mail

"A lovely read. One can only hope this book is the first of many." - The Financial Post

"A must-read for all China watchers." - The Edmonton Journal

"A splendid memoir: funny, self-mocking, biting and perceptive." - The Washington Post

"Totally captivating. A wonderful memoir." - The Globe and Mail

"A lovely read. One can only hope this book is the first of many." - The Financial Post

"A must-read for all China watchers." - The Edmonton Journal

"A splendid memoir: funny, self-mocking, biting and perceptive." - The Washington Post

Descriere

Jan Wong, a Canadian of Chinese descent, went to China as a starry-eyed Maoist in 1972 at the height of the Cultural Revolution. This superb memoir offers a startling--and ironic--account of Wong's rocky six-year romance with Maoism and an engaging portrait of this tumultuous time in Chinese history. of photos.