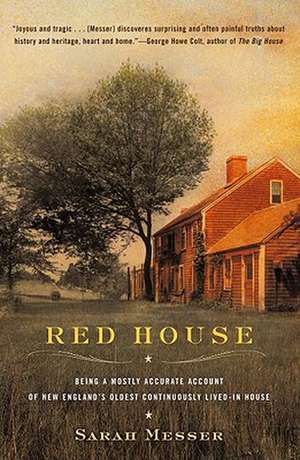

Red House: Being a Mostly Accurate Account of New England's Oldest Continuously Lived-In House

Autor Sarah Messeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2005 – vârsta de la 18 ani

In her critically acclaimed, ingenious memoir, Sarah Messer explores America’s fascination with history, family, and Great Houses. Her Massachusetts childhood home had sheltered the Hatch family for 325 years when her parents bought it in 1965. The will of the house’s original owner, Walter Hatch—which stipulated Red House was to be passed down, "never to be sold or mortgaged from my children and grandchildren forever"—still hung in the living room. In Red House, Messer explores the strange and enriching consequences of growing up with another family’s birthright. Answering the riddle of when shelter becomes first a home and then an identity, Messer has created a classic exploration of heritage, community, and the role architecture plays in our national identity.

Preț: 133.62 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.57€ • 26.69$ • 21.16£

25.57€ • 26.69$ • 21.16£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780142001059

ISBN-10: 0142001058

Pagini: 390

Ilustrații: b/w photos, illustrations, and maps throughout

Dimensiuni: 131 x 196 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

ISBN-10: 0142001058

Pagini: 390

Ilustrații: b/w photos, illustrations, and maps throughout

Dimensiuni: 131 x 196 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Cuprins

Red House Part One

Chapter One: The Land, 1614-1647

Chapter Two: Walter, 1647-1699

Chapter Three: The First Israel, 1667-1740

Chapter Four: The Second Israel, 1701-1767

Chapter Five: The Third Israel, 1730-1809

Chapter Six: Deacon Joel, 1771-1849

Chapter Seven: Israel H., 1837-1921

Chapter Eight

Part Two

Chapter Nine: Israel H., 1837-1921

Chapter Ten: Harris, 1866-1934

Chapter Eleven: Richard Warren Hatch, 1934-1965

Chapter Twelve: The Land, 1932-1935

Chapter Thirteen: Richard Warren Hatch, 1934-1965

Chapter Fourteen

Epilogue

Appendix

Inhabitants of the Red House

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Chapter One: The Land, 1614-1647

Chapter Two: Walter, 1647-1699

Chapter Three: The First Israel, 1667-1740

Chapter Four: The Second Israel, 1701-1767

Chapter Five: The Third Israel, 1730-1809

Chapter Six: Deacon Joel, 1771-1849

Chapter Seven: Israel H., 1837-1921

Chapter Eight

Part Two

Chapter Nine: Israel H., 1837-1921

Chapter Ten: Harris, 1866-1934

Chapter Eleven: Richard Warren Hatch, 1934-1965

Chapter Twelve: The Land, 1932-1935

Chapter Thirteen: Richard Warren Hatch, 1934-1965

Chapter Fourteen

Epilogue

Appendix

Inhabitants of the Red House

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Recenzii

"Red house is the story of America: hopeful, tragic, and persevering. Remarkable and amazing." —Daniel Wallace, author of Big Fish

"A genealogy of home and heart. Impossible to put down. —Terry Ryan, author of The Prize Winner of Defiance Ohio

"An evocative story ... told with a freshness that demonstrates Messer’s skill at humanizing vignettes." —The Boston Globe

"[Messer] discovers surprising and often painful truths about history and heritage, heart and home." —George Howe Colt, author of The Big House

"A genealogy of home and heart. Impossible to put down. —Terry Ryan, author of The Prize Winner of Defiance Ohio

"An evocative story ... told with a freshness that demonstrates Messer’s skill at humanizing vignettes." —The Boston Globe

"[Messer] discovers surprising and often painful truths about history and heritage, heart and home." —George Howe Colt, author of The Big House

Notă biografică

Sarah Messer teaches poetry and creative nonfiction at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. Her poetry has been published in the Kenyon Review, Paris Review, Story, and many other journals. She is the author of a book of poetry, Bandit Letters. She has received a Mary Roberts Rinehart award for Emerging Writers, and grants and fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the American Antiquarian Society, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Extras

One

Before the highway, the oil slick, the outflow pipe; before the blizzard, the sea monster, the Girl Scout camp; before the nudist colony and flower farm; before the tidal wave broke the river's mouth, salting the cedar forest; before the ironworks, tack factory, and shoe-peg mill; before the landing where skinny-dipping white boys jumped through berry bushes; before hayfield, ferry, oyster bed; before Daniel Webster's horses stood buried in their graves; before militiamen's talk of separating; before Unitarians and Quakers, the shipyards and mills, the nineteen barns burned in the Indian raid—even then the Hatches had already built the Red House.

The surname Hatch most commonly means a half-door, or gate, an entrance to a village or manor house. It describes a person who stands by the gate; a person newly born; a person who waits.

My father could not wait. He had made an appointment with a real-estate agent, but when he found himself on a house call in Marshfield, Massachusetts, he decided to see the Red House himself. It was August 1965, and he was a thirty-three-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate with a crew cut and bow tie, married to my mother for just four months. Done with his residency and his army service, he had begun to specialize in radiology— broken bones, mammograms, GI series. The practice of seeing through people. With all the self-consciousness of a latter-day Gatsby, he would eventually raise a herd of kids patchworked together as “New Englanders”—four from his first marriage, four with my mother. But for now he was moonlighting for extra cash and driving his sky-blue VW Beetle down dirt roads, into brambles and dead-ends.

Marshfield, then as now, is a coastal community thirty miles south of Boston, 225 miles north of New York City, whose famous residents over the years have included “The Great Compromiser” Daniel Webster, some Kennedy offspring, and Steve Tyler of Aerosmith. Driving through the north part of town, my father passed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses, two ponds where mills had been. The afternoon light lay drowsy, the air motoring with insects. He knew he was getting close to something, and his stomach clenched. He had always loved ancient rooflines and stone walls, half- collapsed barns—templates of what had come before—plain churches, fields rolling down to rivers, shipyards. Yet, within this two-mile stretch, modern houses and gas stations had grown up around their remains like flesh over bone. He was following his intuition, as if, eyes closed in a dream, he felt his way with his hands stretched out. The road began a violent S-curve at the edge of a string of ponds. At the blind part of the curve, my father found the road to the house, and turned there to begin the half-mile drive past yet another pond.

He drove by the dilapidated Hatch Mill, over the narrow bridge, then through a canopy of crab-apple trees, over a stream that ran beneath the road. It was the last few weeks of summer, and the timothy was high at the roadside, the milkweed setting off parachute seeds.

Meanwhile, in the adjacent town of Norwell, in the apartment he was renting, my mother was preparing his four children for a bath. They were: Kim, seven; Kerry, five; Kate, four; and Patrick, three. The children were spending the summer away from their mother in California. They had been to Martha's Vineyard, Benson's Wild Animal Farm; they had spent the day riding bicycles on the blacktop driveway.

Lately a raccoon had been banging the lids of the garbage cans below the second-floor bathroom window each night. “That raccoon with his black mask, that thief,” they'd say. My mother was relieved: animal stories were common ground. She said, “It's getting dark; do you think the raccoon is out there?” She squeezed Johnson's baby shampoo into one hand, and then turned the water off. The children shrieked, “Raccoon! Raccoon!” Pale-skinned kids with tan lines: Kim, tall, broad-cheekboned; Kerry and Patrick, a girl- and-boy matched pair with the same androgynous haircut; Kate, a tantrum-throwing tow- head.

My mother, twenty-seven years old and petite, wore her hair long, usually in braids or in a large bun with a thin path of gray twisting through it like a skunk stripe. That day she wore it in a ratty ponytail, having had no time to brush it. Her only cosmetics: an occasional eyebrow-penciling, and lipstick in the evening if she was going out. It had been almost four years since my mother, a lab technician, had met my father at the cafeteria in Children's Hospital in Boston. As she stood in line, she saw him leave his dirty plate and tray, linger, exit the cafeteria, and then return to the line. He was wearing his signature bow tie. He approached her and asked her to have lunch with him.

“You already ate,” she said.

“I'll eat again,” he replied.

From the beginning, my father had mentioned his divorce and his custody of the children for school vacations and three months every summer. Early in the relationship, my father had brought my mother and the children to Cape Cod, where she had her own room in the rented cabin. Nearly every night, Kim had sanded and short-sheeted the bed, leaving seaweed and crabs under the blankets. Besides these incidents, though, the children gave her little indication that she was unwanted. Summer was over, and the next day they were returning to California. The bathtub was by the window, and when they stood at the edge, the children could look down on the dented lids of the three garbage cans. My father had said that the house call would take only an hour at most. Now it was getting late, and my mother had no idea where he was.

He rounded the corner at a large white house, turning sharply to the right at a vine- covered lamppost. He drove through two large stones that made a gate. Then, suddenly, the house was before him, rambling to his left along the crest of a ridge. Below, to his right, a yard fell away into a field of ragweed, bullfrogs.

In architectural terms, the house my father saw would be described as a five-bay, double- pile, center-chimney colonial. It had post-and-beam vertical-board construction, a granite foundation, and small-paned windows. The windows were trimmed with chipped white paint, the body of the house was a deep red—Delicious Apple Red, Long Stem Rose Red, Evening Lip-Stick Red, Miss Scarlett Red, a red that neared maroon. Otherwise, the house was plain and, with its the chimney in the middle of the roof against a backdrop of sky, appeared as simple as a child's drawing of a house: big square and triangle, smaller square on top. The cornice seemed the only detail out of place: attached to the doorway as if to elevate the exterior from utilitarian farmhouse to Victorian estate, it hinted at Greek or Roman Revival, something lofty—like a hood ornament on a Dodge Dart.

The house was large and debauched. Four bushes grown shaggy with tendrils sat beneath the first-floor windows. Lilac trees tangled the farthest ell. The driveway wound around the house to the right, where it climbed a small hill. In the backyard, a man and woman sat in lawn chairs drinking old-fashioneds. It was 5 p.m.

My father, stepping out of the rusted VW, might have appeared to Richard Warren Hatch and his wife, Ruth, to be an affable character—friendly and perhaps a bit too unassuming, with a boyish way of loping when he walked. My father was raised in Polo, Illinois, a small farming town known only for its proximity to Dixon, the birthplace of Ronald Reagan. He was six foot two, with dark hair and bright-blue eyes, size-thirteen feet, crooked teeth, prominent ears, and a nose that had been broken seven times playing football. He was the son of a cattle-feed salesman and a grocery-store clerk. In 1948, he was the captain of his high school's undefeated and untied state-champion football team—a 188-pound fullback once described as a “ripping, slashing ball carrier capable of chewing an opponent's line to shreds.” He was from a one-street, one-chicken-fried- steak-restaurant, one-road-leading-out-into-cornfields, one-stand-of-trees, one-historical- marker-from-the-Indian-war, one-railroad-track town. A town with a history of drive-by prairie schooners. More than anything, he had wanted to get out, and probably even now, sixteen years later, he still wore that desire in the face he presented to the unknown, to strangers. Few of my father's ancestors had ever owned anything; his parents still rented the house they'd lived in for twenty years. Harvard had taught him to love tradition and antiquity, and my father was impatient for a life he had only caught glimpses of in the educated accents of professors and the boiled-wool sweaters of his college roommates' parents. He was looking for a piece of history different from the one his own heritage had provided him. He was looking for just this type of New England home.

The older couple did not get up to greet my father when he closed the car door. But they did smile. So he walked up the yard toward the house and their arrangement of chairs. “I've got an appointment to see the house on Monday,” he said. It was now Saturday. “Oh yes,” Richard Warren Hatch said, “we've heard about you.”

R

Inside, the house was low-ceilinged and dark. Hatch led my father through the honeycomb of rooms, past walls with buckled plaster and wide-paneled boards. Doors slanted in their frames, wind blew out the mouths of small fireplaces. Candleholders extended from mantels like robot arms. Rooms opened into more rooms of boxed and hand-hewn beams. A staircase on the north side of the house unfolded itself like a tight, narrow fan, disappearing to the second floor. The house smelled old, the product of its accumulated history—books and talcum powder, wood, silver polish.

Hatch showed my father old photos in which the paint peeled off the house in ribbons, the sides clapboarded and bowed, the trim gone gray. Hatch had hardly led my father through the inside of the house and already he was revealing its history—the way a parent might present to guests his child's baby pictures, framed drawings, and graduation photos arranged along a hallway before introducing the actual child. The photos depicted several driveways ringed with post, fences long gone, absent gates—the house standing starkly in a nude landscape. They showed a house often in disrepair: sagging roofline, loose shingles. In one photo, a barn loomed larger than the house, extending at a right angle toward the pond. The house and the barn together formed an elongated ell. Windows stacked three stories up the barn's flat red side. The roofs glowed grayish in the photo, and in the foreground, hoed rows of a garden extended toward the bottom of the frame. One photo, circa 1900, showed three small children standing in front of the house in long white shifts that glowed like filament against the dark clapboards.

What the photos did not show, of course, was the beginning—the narrowness of the first structure, the forest behind it, the river a distant smudge, the piles of stumps and roots torn out of the ground, the parts that could not be used for shipbuilding knees burned in bonfires. The photos did not show the stones dug out of the earth for cellars and walls. How the house exterior was first covered with boards, or the roof thatched with reeds, or the windows crosshatched. The photos did not show the close-string stairway replacing a ladder, or someone stand-ing too far in the kitchen's giant hearth when the pot spilled and a skirt hem caught flame, burning lard pouring out over the floor. The photos caught occasional in-between moments, but they implied more, and my father, prodded by Hatch, began to imagine the lives of ancestors—Puritans, shipbuilders, somber Victorians—the blurred wheels of a chaise along the lane in a time before telephone poles.

Hatch led my father, finally, to the root cellar beneath the house. They walked through the tin-backed door from the boiler room into what Hatch called “the passageway.” It was more of a tunnel, really, twenty feet long and curving slightly—the stone walls supported by cement and brick. When he extended his arms to the side, my father could touch both walls in the passageway, the stones damp, sweating. My father was fidgeting, talking too much.

“My parents lived in Chicago,” he said. “They never finished high school.”

The passageway opened into a large underground room where stood part of a chimney, the carved-out kettle drum of the original cellar behind a stairway of half-log beams that led up to a trapdoor in the ceiling, which was the floor of a closet in a room above them. It was the most primitive part of the house. The room smelled of something sweet and dank. Several potatoes grew eyes in the corner. Wires stapled to the underside of boards of the floor above snarled with webs, the mummified bodies of spiders.

“My father played poker with John Dillinger,” my father said. “During the Depression, he had a general store that went under.”

“These are very old beams,” Hatch said, pointing up. “They're part of the original cellar and structure of the old part of the house.”

My father stopped, looked up at the beams.

“My mother, you know, she has a heart condition—rheumatoid, arrhythmia.”

Hatch nodded, seemed distracted. He was built like a ladder. A bunch of wiry hair grew out of his eyebrows. Whenever he talked, his voice boomed off stone, as if the volume were turned up too loud in the room. My father found himself nodding; the tone of Hatch's voice was one of antiquarian authority.

My father, a storyteller, thought of narratives he could recycle in the appropriate occasion. “One time . . .” Or “I once knew this crazy guy . . .” But he had learned Hatch was a writer; had been the head of the English department at Deerfield Academy from 1925 to 1941; had served aboard the battleship New Mexico and the aircraft carrier Yorktown in World War II; had been married with kids and divorced; had since 1951 lectured at the Center for International Studies at MIT, researching and writing about U.S. foreign policy. He had more stories to tell than my father.

Earlier, Hatch had told my father that his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Walter Hatch had built the house in 1647; that it had always been called the “Red House”; that it was one of the first houses built in this area called Two Mile, which was also casually referred to as “Hatchville” thanks to prolific and intermarrying progeny. As a testament to this, Walter Hatch's framed will, dated 1681 and written in legal English, hung on the living-room wall as it always had, stating that the house should be passed on to “heirs begotten of my body forever from generation to generation to the world's end never to be sold or mortgaged from my children and grandchildren forever.” While talking to my father, Hatch had traced the lines of the will with his finger. My father was having difficulty absorbing everything. He gazed at the will, the paper the color of a grocery bag trapped under the glass now streaked with Hatch's fingermarks.

“This house has been in my family for eight generations,” Hatch repeated, delivering his most subtle sales pitch. “The Oldest Continuously Lived-In House in New England,” he said.

On the cement floor beneath my father's feet, Hatch's two sons had carved their names in cement: “Dick and Toph '41.” If the house had been in the family for over three hundred years, my father wondered, why was Hatch going against the weight of tradition and selling it? But he kept his mouth shut, fearing that Hatch would suddenly snap out of it, change his mind.

“I need to talk with my wife,” my father said.

R

The distance from the Red House to the apartment my parents were renting was five miles. My father turned off the rattling VW motor and coasted into the driveway. Then he rounded the corner of the house and stood under the second-floor window by the garbage cans. He grabbed the lids and smashed them together. Inside, the children rushed to the window—“raccoon, raccoon!”—bare feet across the floor. Instead they saw their father in tan corduroys and bow tie, a lid in each hand. He saw their faces crowding the panes, their hands on the glass. He entered the apartment through the back door, ran up the stairs to the kitchen, and shouted my mother's nickname: “Scout, Scout!” He insisted she and the kids come see the house, dressed as they were in pajamas and slippers. He said, “This house . . . ,” standing there with his elbows at his side, hands clenched before him, as if he were holding ski poles, skiing in place, one foot, then the other slaloming the floorboards. “Come now,” was all he could say.

Patrick followed his sisters and stepmother downstairs to the driveway, dragging the worn remnant of a stuffed animal behind him. “You've got to see it,” my father said. Then, suddenly, they were bumping along in the crowded VW. My mother had Patrick on her lap with the hairless toy. “Who is this?” she asked.

“Rabbit,” said Patrick.

My mother looked at herself in the tiny square mirror on the sun visor and saw behind her the three girls flopped over each other in the back seat. Patrick dropped the rabbit between her knees, where he saw bits of road through the rusted floor-holes. “Uh . . . nope!” my mother said, as she pinched her knees and caught the toy.

My mother never spoke about herself, and when speaking with others was forthright and blunt, often offending listeners unintentionally with her honesty. This habit was derived from her attempt to lose her “Southernness”—the friendly openness, the drawn-out syllables. She would rather say nothing, or say something sharp, because she really believed her Southernness was a cliché, and it reminded her of her childhood, which she preferred to forget.

All my mother ever said about my grandmother was that she divorced my grandfather in order to marry her second cousin, had a thick Southern accent, smoked two packs of Camel no-filters a day, kept a shot glass of whiskey at her side, and died when my mother was twenty-two.

“We were,” as she often put it, “a bunch of Georgia crackers.”

After her parents' divorce, my mother moved with her mother and stepfather to Allapattah, Florida. She was eight years old and spent most of her time weaving through kumquat hedges behind the apartment building, or sitting in the mulberry tree with a neighbor girl who lived in a house with an old stove tossed in the front yard—no toilet or running water. They would sit all day in the tree, pelting fruit at the stove and getting stains on their hands, until one day my mother got head lice and wasn't allowed to see the girl again. “White trash,” her stepfather said, and my mother thought about the stove they had just thrown in their yard, which was white enamel. White trash. Yet, the next year, they moved to a housing project in North Miami where all the buildings were one-story cinder block built on coral rock and barbed grass. Behind the development, through a thin strand of trees, sat a working slaughterhouse on the edge of a rust-brown river. Bits of hoof and bone chips had been carried off by dogs, scattered on the banks. Her only brother dared her to swing across the “river of blood,” as he called it, holding a rope swing tied to a tree. She watched a series of her brother's friends swing out and over to the other side. Then she did and missed, fell up to her knees in slime and viscera, had to bury her stained tennis sneakers in the woods so her mother would not know.

By sixteen, my mother had developed the habit of hanging out with bikers. When her father saw her wearing pink leather pants, she was immediately sent to a girls' school in Virginia, where she learned the correct posture for walking downstairs in pumps, how to get out of a car while wearing a skirt. She graduated from high school, went to junior college, then transferred at nineteen to an elite private college in Vermont.

When she arrived at the college, she possessed seven pairs of elbow-length gloves dyed in pastel colors to match her collection of semiformal dresses, but no one had ever told her about snow. Sometime in late October 1957, seeing snow fall for the first time, she rushed out of the dormitory wearing canvas tennis sneakers, no socks. After a forty-five- minute snowball fight, she was taken to the clinic and diagnosed with frostbite.

She compensated for this naïveté with toughness and nonplussed Southern denial—“I'll just put that out of my mind,” she'd say, as if determining, since leaving the South, that nothing was going to bother her anymore. The result was very Yankee-tomboy. She was always Pat—never Patricia, or Patty, or Patsy—and eventually she rejected that for Scout. As in: hunter/tracker; the girl in To Kill a Mockingbird, a book my father happened to be reading the day he asked her out. In photos taken before they were married, she sported a boy's haircut and held a rifle at her side. A series of photos shows her taking aim and knocking off rounds of clay pigeons.

Now, three years later, her arm out the window of the Volkswagen, she traced the landscape on the way to the house. Absentmindedly, she aimed. They were passing fields of tall grass, square colonial houses, stone walls. The sky was growing gray; her eye caught the spark of a firefly at the roadside.

“The kids are falling asleep,” she said, pulling her arm back in.

R

They arrived at the Red House to find the Hatches exactly where my father had first seen them: sitting in chairs on the lawn, halfway through their drinks, eating cheese and crackers. My mother stood with her hands on someone's small shoulders, introducing herself and the children.

In the yard behind them, two apple trees stretched their umbrellas over a carpet of wormy green-apple windfalls. The children were told to stand by the apple trees. My father and mother disappeared into the house with Mr. Hatch. The kids made little piles of apples. Ruth Hatch stood nearby, clasping her hands, her soft white hair swept up.

Richard Warren Hatch brought my parents through the east ell to a modern kitchen, and then into the older portion of the house. Stepping over the threshold, my mother noticed crooked doorways and floors. A half-model of a ship pushed out of the fireplace mantel. When he would talk about that day, my father always said, “You could tell that they really liked us. And we really liked them. I think the fact that he had been married before and then was divorced . . . I think he looked at us with the knowledge that I had been married before, and he was very open-minded.”

“We moved all the time when I was a child,” my mother heard herself say aloud, though in reality she only had moved three times. Yet this house seemed permanent. On the north side, a stairwell rose, nine curved steps, to the second floor with its bedrooms. She was in the attic, and then, just as suddenly, she was down a staircase and back in the living room, where windows stared out into the backyard. To her back was the dining room, where she had entered; to her left, a desk scattered with papers and several unplugged lamps.

Outside the house the children were silent, wandering between the apple trees and stepping barefoot over mashed apples. Patrick stuck his arm into a hole in the tree and pulled it back out. The air carried the smell of marsh; they walked to the edge of the meadow, looking for ferns.

My mother and father left the house and crossed the lawn, where they talked behind a bush.

“What do you think?” he whispered. “Do you want to buy it?” He grabbed her arm, brought his face close to hers. My mother kept glancing at the children.

Hatch asked Kim to go with them—him and my father—for a walk down into the woods. “I'll show you the clearing,” he said, “and the Indian burial ground.”

Kim walked between them past a meadow and into the pines, the carpet of needles. They walked along a stone wall. Hatch described the salt hay that had stretched down to the river and the “rabbit runs”: mounds of earth piled up for bridges across marshes, and used for the shipbuilding trade.

“Those rabbits like high ground,” Hatch said, looking at Kim and winking. Kim imagined legions of rabbits building small rabbit-ships.

They traveled down a hill, where the road curved and the wall broke open, and found another gate. They walked through trees and into a large clearing. Here clumps of soft grass and moss grew around fieldstones and overturned granite posts.

“This is an Indian burial ground,” Hatch said. “Go and play.” He was talking to my father in serious tones, occasionally looking toward Kim and shouting, “You might find an arrowhead! Go ahead and look.” Kim walked on top of a few of the sidelined slabs of granite. She dug her hand down into a clump of grass, where she felt roots, a rock.

The rock was pink with white veins running through it like pork fat. “You mean like this one?” she asked, holding it up in her hand. Upside down, it could have been a heart. They were talking about the house, she realized, about money. “I found an arrowhead!”

“Well, I'll be darned,” said Hatch. “Nobody has found an arrowhead down here for twenty years.”

R

My mother wished that she could brush her hair. She excused herself from Ruth and went into the bathroom off the kitchen. There she found a blue plastic comb on the sink, picked it up, put it back down. It was getting dark outside, all the light seeping out. She took the elastic band out of her hair, ran her fingers through it, and put the elastic back in.

Outside, she heard Hatch's deep voice. He was telling Ruth and the children about Kim's arrowhead. Kim held out her palm to them but did not let anyone touch it. It was night now; the bats were out, swooping as if pulled by strings. My father was at my mother's side again, asking her the same question about the house: “Should we get it?”

That summer, they had been discussing moving to Berkeley, California, to be closer to his children. In fact, they had been sure of it. My father had already accepted a position at a San Francisco hospital, and was scheduled to begin in October. Now, in one night, in a few hours of walking through a house, he was changing his mind. She looked at him, studying his face. She knew he was impulsive, but he'd never done anything like this before.

“Decide where you want to live,” she said. There were houses, she knew, that you bought simply to inhabit—apartments or houses like those she had grown up in—nothing special. And then there were houses that could change your life: the rooms, the walls, the roof, the land, and view from its windows could reshape you, mold you. This house was older than most of New England; it wasn't the kind of house you just bought and sold. If they bought this house, my mother was certain they'd have to live in it for the rest of their lives.

Across the lawn she saw the glow of the children's pajamas against the dark shape of trees and the roofline.

“It's your decision,” she said, finally.

“This is where I want to live,” he answered.

Before the highway, the oil slick, the outflow pipe; before the blizzard, the sea monster, the Girl Scout camp; before the nudist colony and flower farm; before the tidal wave broke the river's mouth, salting the cedar forest; before the ironworks, tack factory, and shoe-peg mill; before the landing where skinny-dipping white boys jumped through berry bushes; before hayfield, ferry, oyster bed; before Daniel Webster's horses stood buried in their graves; before militiamen's talk of separating; before Unitarians and Quakers, the shipyards and mills, the nineteen barns burned in the Indian raid—even then the Hatches had already built the Red House.

The surname Hatch most commonly means a half-door, or gate, an entrance to a village or manor house. It describes a person who stands by the gate; a person newly born; a person who waits.

My father could not wait. He had made an appointment with a real-estate agent, but when he found himself on a house call in Marshfield, Massachusetts, he decided to see the Red House himself. It was August 1965, and he was a thirty-three-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate with a crew cut and bow tie, married to my mother for just four months. Done with his residency and his army service, he had begun to specialize in radiology— broken bones, mammograms, GI series. The practice of seeing through people. With all the self-consciousness of a latter-day Gatsby, he would eventually raise a herd of kids patchworked together as “New Englanders”—four from his first marriage, four with my mother. But for now he was moonlighting for extra cash and driving his sky-blue VW Beetle down dirt roads, into brambles and dead-ends.

Marshfield, then as now, is a coastal community thirty miles south of Boston, 225 miles north of New York City, whose famous residents over the years have included “The Great Compromiser” Daniel Webster, some Kennedy offspring, and Steve Tyler of Aerosmith. Driving through the north part of town, my father passed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses, two ponds where mills had been. The afternoon light lay drowsy, the air motoring with insects. He knew he was getting close to something, and his stomach clenched. He had always loved ancient rooflines and stone walls, half- collapsed barns—templates of what had come before—plain churches, fields rolling down to rivers, shipyards. Yet, within this two-mile stretch, modern houses and gas stations had grown up around their remains like flesh over bone. He was following his intuition, as if, eyes closed in a dream, he felt his way with his hands stretched out. The road began a violent S-curve at the edge of a string of ponds. At the blind part of the curve, my father found the road to the house, and turned there to begin the half-mile drive past yet another pond.

He drove by the dilapidated Hatch Mill, over the narrow bridge, then through a canopy of crab-apple trees, over a stream that ran beneath the road. It was the last few weeks of summer, and the timothy was high at the roadside, the milkweed setting off parachute seeds.

Meanwhile, in the adjacent town of Norwell, in the apartment he was renting, my mother was preparing his four children for a bath. They were: Kim, seven; Kerry, five; Kate, four; and Patrick, three. The children were spending the summer away from their mother in California. They had been to Martha's Vineyard, Benson's Wild Animal Farm; they had spent the day riding bicycles on the blacktop driveway.

Lately a raccoon had been banging the lids of the garbage cans below the second-floor bathroom window each night. “That raccoon with his black mask, that thief,” they'd say. My mother was relieved: animal stories were common ground. She said, “It's getting dark; do you think the raccoon is out there?” She squeezed Johnson's baby shampoo into one hand, and then turned the water off. The children shrieked, “Raccoon! Raccoon!” Pale-skinned kids with tan lines: Kim, tall, broad-cheekboned; Kerry and Patrick, a girl- and-boy matched pair with the same androgynous haircut; Kate, a tantrum-throwing tow- head.

My mother, twenty-seven years old and petite, wore her hair long, usually in braids or in a large bun with a thin path of gray twisting through it like a skunk stripe. That day she wore it in a ratty ponytail, having had no time to brush it. Her only cosmetics: an occasional eyebrow-penciling, and lipstick in the evening if she was going out. It had been almost four years since my mother, a lab technician, had met my father at the cafeteria in Children's Hospital in Boston. As she stood in line, she saw him leave his dirty plate and tray, linger, exit the cafeteria, and then return to the line. He was wearing his signature bow tie. He approached her and asked her to have lunch with him.

“You already ate,” she said.

“I'll eat again,” he replied.

From the beginning, my father had mentioned his divorce and his custody of the children for school vacations and three months every summer. Early in the relationship, my father had brought my mother and the children to Cape Cod, where she had her own room in the rented cabin. Nearly every night, Kim had sanded and short-sheeted the bed, leaving seaweed and crabs under the blankets. Besides these incidents, though, the children gave her little indication that she was unwanted. Summer was over, and the next day they were returning to California. The bathtub was by the window, and when they stood at the edge, the children could look down on the dented lids of the three garbage cans. My father had said that the house call would take only an hour at most. Now it was getting late, and my mother had no idea where he was.

He rounded the corner at a large white house, turning sharply to the right at a vine- covered lamppost. He drove through two large stones that made a gate. Then, suddenly, the house was before him, rambling to his left along the crest of a ridge. Below, to his right, a yard fell away into a field of ragweed, bullfrogs.

In architectural terms, the house my father saw would be described as a five-bay, double- pile, center-chimney colonial. It had post-and-beam vertical-board construction, a granite foundation, and small-paned windows. The windows were trimmed with chipped white paint, the body of the house was a deep red—Delicious Apple Red, Long Stem Rose Red, Evening Lip-Stick Red, Miss Scarlett Red, a red that neared maroon. Otherwise, the house was plain and, with its the chimney in the middle of the roof against a backdrop of sky, appeared as simple as a child's drawing of a house: big square and triangle, smaller square on top. The cornice seemed the only detail out of place: attached to the doorway as if to elevate the exterior from utilitarian farmhouse to Victorian estate, it hinted at Greek or Roman Revival, something lofty—like a hood ornament on a Dodge Dart.

The house was large and debauched. Four bushes grown shaggy with tendrils sat beneath the first-floor windows. Lilac trees tangled the farthest ell. The driveway wound around the house to the right, where it climbed a small hill. In the backyard, a man and woman sat in lawn chairs drinking old-fashioneds. It was 5 p.m.

My father, stepping out of the rusted VW, might have appeared to Richard Warren Hatch and his wife, Ruth, to be an affable character—friendly and perhaps a bit too unassuming, with a boyish way of loping when he walked. My father was raised in Polo, Illinois, a small farming town known only for its proximity to Dixon, the birthplace of Ronald Reagan. He was six foot two, with dark hair and bright-blue eyes, size-thirteen feet, crooked teeth, prominent ears, and a nose that had been broken seven times playing football. He was the son of a cattle-feed salesman and a grocery-store clerk. In 1948, he was the captain of his high school's undefeated and untied state-champion football team—a 188-pound fullback once described as a “ripping, slashing ball carrier capable of chewing an opponent's line to shreds.” He was from a one-street, one-chicken-fried- steak-restaurant, one-road-leading-out-into-cornfields, one-stand-of-trees, one-historical- marker-from-the-Indian-war, one-railroad-track town. A town with a history of drive-by prairie schooners. More than anything, he had wanted to get out, and probably even now, sixteen years later, he still wore that desire in the face he presented to the unknown, to strangers. Few of my father's ancestors had ever owned anything; his parents still rented the house they'd lived in for twenty years. Harvard had taught him to love tradition and antiquity, and my father was impatient for a life he had only caught glimpses of in the educated accents of professors and the boiled-wool sweaters of his college roommates' parents. He was looking for a piece of history different from the one his own heritage had provided him. He was looking for just this type of New England home.

The older couple did not get up to greet my father when he closed the car door. But they did smile. So he walked up the yard toward the house and their arrangement of chairs. “I've got an appointment to see the house on Monday,” he said. It was now Saturday. “Oh yes,” Richard Warren Hatch said, “we've heard about you.”

R

Inside, the house was low-ceilinged and dark. Hatch led my father through the honeycomb of rooms, past walls with buckled plaster and wide-paneled boards. Doors slanted in their frames, wind blew out the mouths of small fireplaces. Candleholders extended from mantels like robot arms. Rooms opened into more rooms of boxed and hand-hewn beams. A staircase on the north side of the house unfolded itself like a tight, narrow fan, disappearing to the second floor. The house smelled old, the product of its accumulated history—books and talcum powder, wood, silver polish.

Hatch showed my father old photos in which the paint peeled off the house in ribbons, the sides clapboarded and bowed, the trim gone gray. Hatch had hardly led my father through the inside of the house and already he was revealing its history—the way a parent might present to guests his child's baby pictures, framed drawings, and graduation photos arranged along a hallway before introducing the actual child. The photos depicted several driveways ringed with post, fences long gone, absent gates—the house standing starkly in a nude landscape. They showed a house often in disrepair: sagging roofline, loose shingles. In one photo, a barn loomed larger than the house, extending at a right angle toward the pond. The house and the barn together formed an elongated ell. Windows stacked three stories up the barn's flat red side. The roofs glowed grayish in the photo, and in the foreground, hoed rows of a garden extended toward the bottom of the frame. One photo, circa 1900, showed three small children standing in front of the house in long white shifts that glowed like filament against the dark clapboards.

What the photos did not show, of course, was the beginning—the narrowness of the first structure, the forest behind it, the river a distant smudge, the piles of stumps and roots torn out of the ground, the parts that could not be used for shipbuilding knees burned in bonfires. The photos did not show the stones dug out of the earth for cellars and walls. How the house exterior was first covered with boards, or the roof thatched with reeds, or the windows crosshatched. The photos did not show the close-string stairway replacing a ladder, or someone stand-ing too far in the kitchen's giant hearth when the pot spilled and a skirt hem caught flame, burning lard pouring out over the floor. The photos caught occasional in-between moments, but they implied more, and my father, prodded by Hatch, began to imagine the lives of ancestors—Puritans, shipbuilders, somber Victorians—the blurred wheels of a chaise along the lane in a time before telephone poles.

Hatch led my father, finally, to the root cellar beneath the house. They walked through the tin-backed door from the boiler room into what Hatch called “the passageway.” It was more of a tunnel, really, twenty feet long and curving slightly—the stone walls supported by cement and brick. When he extended his arms to the side, my father could touch both walls in the passageway, the stones damp, sweating. My father was fidgeting, talking too much.

“My parents lived in Chicago,” he said. “They never finished high school.”

The passageway opened into a large underground room where stood part of a chimney, the carved-out kettle drum of the original cellar behind a stairway of half-log beams that led up to a trapdoor in the ceiling, which was the floor of a closet in a room above them. It was the most primitive part of the house. The room smelled of something sweet and dank. Several potatoes grew eyes in the corner. Wires stapled to the underside of boards of the floor above snarled with webs, the mummified bodies of spiders.

“My father played poker with John Dillinger,” my father said. “During the Depression, he had a general store that went under.”

“These are very old beams,” Hatch said, pointing up. “They're part of the original cellar and structure of the old part of the house.”

My father stopped, looked up at the beams.

“My mother, you know, she has a heart condition—rheumatoid, arrhythmia.”

Hatch nodded, seemed distracted. He was built like a ladder. A bunch of wiry hair grew out of his eyebrows. Whenever he talked, his voice boomed off stone, as if the volume were turned up too loud in the room. My father found himself nodding; the tone of Hatch's voice was one of antiquarian authority.

My father, a storyteller, thought of narratives he could recycle in the appropriate occasion. “One time . . .” Or “I once knew this crazy guy . . .” But he had learned Hatch was a writer; had been the head of the English department at Deerfield Academy from 1925 to 1941; had served aboard the battleship New Mexico and the aircraft carrier Yorktown in World War II; had been married with kids and divorced; had since 1951 lectured at the Center for International Studies at MIT, researching and writing about U.S. foreign policy. He had more stories to tell than my father.

Earlier, Hatch had told my father that his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Walter Hatch had built the house in 1647; that it had always been called the “Red House”; that it was one of the first houses built in this area called Two Mile, which was also casually referred to as “Hatchville” thanks to prolific and intermarrying progeny. As a testament to this, Walter Hatch's framed will, dated 1681 and written in legal English, hung on the living-room wall as it always had, stating that the house should be passed on to “heirs begotten of my body forever from generation to generation to the world's end never to be sold or mortgaged from my children and grandchildren forever.” While talking to my father, Hatch had traced the lines of the will with his finger. My father was having difficulty absorbing everything. He gazed at the will, the paper the color of a grocery bag trapped under the glass now streaked with Hatch's fingermarks.

“This house has been in my family for eight generations,” Hatch repeated, delivering his most subtle sales pitch. “The Oldest Continuously Lived-In House in New England,” he said.

On the cement floor beneath my father's feet, Hatch's two sons had carved their names in cement: “Dick and Toph '41.” If the house had been in the family for over three hundred years, my father wondered, why was Hatch going against the weight of tradition and selling it? But he kept his mouth shut, fearing that Hatch would suddenly snap out of it, change his mind.

“I need to talk with my wife,” my father said.

R

The distance from the Red House to the apartment my parents were renting was five miles. My father turned off the rattling VW motor and coasted into the driveway. Then he rounded the corner of the house and stood under the second-floor window by the garbage cans. He grabbed the lids and smashed them together. Inside, the children rushed to the window—“raccoon, raccoon!”—bare feet across the floor. Instead they saw their father in tan corduroys and bow tie, a lid in each hand. He saw their faces crowding the panes, their hands on the glass. He entered the apartment through the back door, ran up the stairs to the kitchen, and shouted my mother's nickname: “Scout, Scout!” He insisted she and the kids come see the house, dressed as they were in pajamas and slippers. He said, “This house . . . ,” standing there with his elbows at his side, hands clenched before him, as if he were holding ski poles, skiing in place, one foot, then the other slaloming the floorboards. “Come now,” was all he could say.

Patrick followed his sisters and stepmother downstairs to the driveway, dragging the worn remnant of a stuffed animal behind him. “You've got to see it,” my father said. Then, suddenly, they were bumping along in the crowded VW. My mother had Patrick on her lap with the hairless toy. “Who is this?” she asked.

“Rabbit,” said Patrick.

My mother looked at herself in the tiny square mirror on the sun visor and saw behind her the three girls flopped over each other in the back seat. Patrick dropped the rabbit between her knees, where he saw bits of road through the rusted floor-holes. “Uh . . . nope!” my mother said, as she pinched her knees and caught the toy.

My mother never spoke about herself, and when speaking with others was forthright and blunt, often offending listeners unintentionally with her honesty. This habit was derived from her attempt to lose her “Southernness”—the friendly openness, the drawn-out syllables. She would rather say nothing, or say something sharp, because she really believed her Southernness was a cliché, and it reminded her of her childhood, which she preferred to forget.

All my mother ever said about my grandmother was that she divorced my grandfather in order to marry her second cousin, had a thick Southern accent, smoked two packs of Camel no-filters a day, kept a shot glass of whiskey at her side, and died when my mother was twenty-two.

“We were,” as she often put it, “a bunch of Georgia crackers.”

After her parents' divorce, my mother moved with her mother and stepfather to Allapattah, Florida. She was eight years old and spent most of her time weaving through kumquat hedges behind the apartment building, or sitting in the mulberry tree with a neighbor girl who lived in a house with an old stove tossed in the front yard—no toilet or running water. They would sit all day in the tree, pelting fruit at the stove and getting stains on their hands, until one day my mother got head lice and wasn't allowed to see the girl again. “White trash,” her stepfather said, and my mother thought about the stove they had just thrown in their yard, which was white enamel. White trash. Yet, the next year, they moved to a housing project in North Miami where all the buildings were one-story cinder block built on coral rock and barbed grass. Behind the development, through a thin strand of trees, sat a working slaughterhouse on the edge of a rust-brown river. Bits of hoof and bone chips had been carried off by dogs, scattered on the banks. Her only brother dared her to swing across the “river of blood,” as he called it, holding a rope swing tied to a tree. She watched a series of her brother's friends swing out and over to the other side. Then she did and missed, fell up to her knees in slime and viscera, had to bury her stained tennis sneakers in the woods so her mother would not know.

By sixteen, my mother had developed the habit of hanging out with bikers. When her father saw her wearing pink leather pants, she was immediately sent to a girls' school in Virginia, where she learned the correct posture for walking downstairs in pumps, how to get out of a car while wearing a skirt. She graduated from high school, went to junior college, then transferred at nineteen to an elite private college in Vermont.

When she arrived at the college, she possessed seven pairs of elbow-length gloves dyed in pastel colors to match her collection of semiformal dresses, but no one had ever told her about snow. Sometime in late October 1957, seeing snow fall for the first time, she rushed out of the dormitory wearing canvas tennis sneakers, no socks. After a forty-five- minute snowball fight, she was taken to the clinic and diagnosed with frostbite.

She compensated for this naïveté with toughness and nonplussed Southern denial—“I'll just put that out of my mind,” she'd say, as if determining, since leaving the South, that nothing was going to bother her anymore. The result was very Yankee-tomboy. She was always Pat—never Patricia, or Patty, or Patsy—and eventually she rejected that for Scout. As in: hunter/tracker; the girl in To Kill a Mockingbird, a book my father happened to be reading the day he asked her out. In photos taken before they were married, she sported a boy's haircut and held a rifle at her side. A series of photos shows her taking aim and knocking off rounds of clay pigeons.

Now, three years later, her arm out the window of the Volkswagen, she traced the landscape on the way to the house. Absentmindedly, she aimed. They were passing fields of tall grass, square colonial houses, stone walls. The sky was growing gray; her eye caught the spark of a firefly at the roadside.

“The kids are falling asleep,” she said, pulling her arm back in.

R

They arrived at the Red House to find the Hatches exactly where my father had first seen them: sitting in chairs on the lawn, halfway through their drinks, eating cheese and crackers. My mother stood with her hands on someone's small shoulders, introducing herself and the children.

In the yard behind them, two apple trees stretched their umbrellas over a carpet of wormy green-apple windfalls. The children were told to stand by the apple trees. My father and mother disappeared into the house with Mr. Hatch. The kids made little piles of apples. Ruth Hatch stood nearby, clasping her hands, her soft white hair swept up.

Richard Warren Hatch brought my parents through the east ell to a modern kitchen, and then into the older portion of the house. Stepping over the threshold, my mother noticed crooked doorways and floors. A half-model of a ship pushed out of the fireplace mantel. When he would talk about that day, my father always said, “You could tell that they really liked us. And we really liked them. I think the fact that he had been married before and then was divorced . . . I think he looked at us with the knowledge that I had been married before, and he was very open-minded.”

“We moved all the time when I was a child,” my mother heard herself say aloud, though in reality she only had moved three times. Yet this house seemed permanent. On the north side, a stairwell rose, nine curved steps, to the second floor with its bedrooms. She was in the attic, and then, just as suddenly, she was down a staircase and back in the living room, where windows stared out into the backyard. To her back was the dining room, where she had entered; to her left, a desk scattered with papers and several unplugged lamps.

Outside the house the children were silent, wandering between the apple trees and stepping barefoot over mashed apples. Patrick stuck his arm into a hole in the tree and pulled it back out. The air carried the smell of marsh; they walked to the edge of the meadow, looking for ferns.

My mother and father left the house and crossed the lawn, where they talked behind a bush.

“What do you think?” he whispered. “Do you want to buy it?” He grabbed her arm, brought his face close to hers. My mother kept glancing at the children.

Hatch asked Kim to go with them—him and my father—for a walk down into the woods. “I'll show you the clearing,” he said, “and the Indian burial ground.”

Kim walked between them past a meadow and into the pines, the carpet of needles. They walked along a stone wall. Hatch described the salt hay that had stretched down to the river and the “rabbit runs”: mounds of earth piled up for bridges across marshes, and used for the shipbuilding trade.

“Those rabbits like high ground,” Hatch said, looking at Kim and winking. Kim imagined legions of rabbits building small rabbit-ships.

They traveled down a hill, where the road curved and the wall broke open, and found another gate. They walked through trees and into a large clearing. Here clumps of soft grass and moss grew around fieldstones and overturned granite posts.

“This is an Indian burial ground,” Hatch said. “Go and play.” He was talking to my father in serious tones, occasionally looking toward Kim and shouting, “You might find an arrowhead! Go ahead and look.” Kim walked on top of a few of the sidelined slabs of granite. She dug her hand down into a clump of grass, where she felt roots, a rock.

The rock was pink with white veins running through it like pork fat. “You mean like this one?” she asked, holding it up in her hand. Upside down, it could have been a heart. They were talking about the house, she realized, about money. “I found an arrowhead!”

“Well, I'll be darned,” said Hatch. “Nobody has found an arrowhead down here for twenty years.”

R

My mother wished that she could brush her hair. She excused herself from Ruth and went into the bathroom off the kitchen. There she found a blue plastic comb on the sink, picked it up, put it back down. It was getting dark outside, all the light seeping out. She took the elastic band out of her hair, ran her fingers through it, and put the elastic back in.

Outside, she heard Hatch's deep voice. He was telling Ruth and the children about Kim's arrowhead. Kim held out her palm to them but did not let anyone touch it. It was night now; the bats were out, swooping as if pulled by strings. My father was at my mother's side again, asking her the same question about the house: “Should we get it?”

That summer, they had been discussing moving to Berkeley, California, to be closer to his children. In fact, they had been sure of it. My father had already accepted a position at a San Francisco hospital, and was scheduled to begin in October. Now, in one night, in a few hours of walking through a house, he was changing his mind. She looked at him, studying his face. She knew he was impulsive, but he'd never done anything like this before.

“Decide where you want to live,” she said. There were houses, she knew, that you bought simply to inhabit—apartments or houses like those she had grown up in—nothing special. And then there were houses that could change your life: the rooms, the walls, the roof, the land, and view from its windows could reshape you, mold you. This house was older than most of New England; it wasn't the kind of house you just bought and sold. If they bought this house, my mother was certain they'd have to live in it for the rest of their lives.

Across the lawn she saw the glow of the children's pajamas against the dark shape of trees and the roofline.

“It's your decision,” she said, finally.

“This is where I want to live,” he answered.

Descriere

With a poet's eye for clever detail and an ear for the rhythm of place and language, Messer's work of living history tells the story of an American family--whose ancestral home was purchased by her parents--dating back to its wild beginnings in colonial New England. Photos & illustrations.