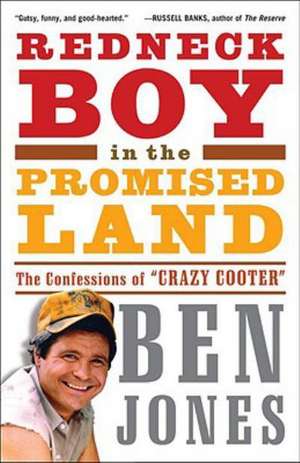

Redneck Boy in the Promised Land: The Confessions of "Crazy Cooter"

Autor Ben Jonesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2034

Millions of people know Ben Jones from his memorable role in the television classic The Dukes of Hazzard as well as his career in the U.S. Congress. But many are unaware of the true-life adventurous past of “Crazy Cooter.” Redneck Boy in the Promised Land is filled with stories about Jones’s experience growing up in the hardscrabble South, surviving the rambunctious sixties–as well as alcoholism and addiction–his unlikely career in show business, his undertakings in politics and Congress, and so much more. In the end, as he says, it was one good ol’ boy’s struggle against himself.

Written with naked honesty and wry humor, Redneck Boy in the Promised Land is Jones’s remarkable tale of falling flat on his face, picking himself up, and finding his way to the American dream while fighting for civil rights, the plight of the working class, “real” Southern culture, and the rights of rednecks everywhere.

Preț: 78.31 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.98€ • 15.70$ • 12.39£

14.98€ • 15.70$ • 12.39£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307395283

ISBN-10: 0307395286

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE 4-COLOR PHOTO INSERTS

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group

Colecția Three Rivers Press

ISBN-10: 0307395286

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE 4-COLOR PHOTO INSERTS

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group

Colecția Three Rivers Press

Recenzii

“Best known as Cooter, the good ol’ boy mechanic on The Dukes of Hazzard …. [Jones] engagingly zips through his destitute boyhood in the segregated South and his days as an alcoholic civil rights activist [and] recounts his transformation from boozin’, brawlin’ womanizer to successful actor to two-term Democratic congressman from Georgia.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Growing up in Georgia, 'Cooter' was one of my heroes. I’m not sure, but I think it was required by law. Who would have thought that one day I would actually come to know Ben Jones, and, in knowing him, find that he remains one of my heroes. You’ll understand why when you read this book. Ben Jones is nothing less than a great American.”

—Jeff Foxworthy, author of Jeff Foxworthy’s Redneck Dictionary

"Ben Jones and I go way back, before anyone called him "Cooter" or "Congressman". He always told the truth. A little on the slant, maybe, which only made it more interesting. And like the wildboy I knew then, his book, Redneck Boy in the Promised Land, is gutsy, funny, and good-hearted. And definitely reader-friendly."

—Russell Banks, author of The Reserve

“This modern-day Will Rogers writes with a mix of humor, pathos, and passion in a rip-roarin’ book with a down-home flavor.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A warm, witty portrait of a quietly extraordinary American life.”

—Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.

—Entertainment Weekly

“Growing up in Georgia, 'Cooter' was one of my heroes. I’m not sure, but I think it was required by law. Who would have thought that one day I would actually come to know Ben Jones, and, in knowing him, find that he remains one of my heroes. You’ll understand why when you read this book. Ben Jones is nothing less than a great American.”

—Jeff Foxworthy, author of Jeff Foxworthy’s Redneck Dictionary

"Ben Jones and I go way back, before anyone called him "Cooter" or "Congressman". He always told the truth. A little on the slant, maybe, which only made it more interesting. And like the wildboy I knew then, his book, Redneck Boy in the Promised Land, is gutsy, funny, and good-hearted. And definitely reader-friendly."

—Russell Banks, author of The Reserve

“This modern-day Will Rogers writes with a mix of humor, pathos, and passion in a rip-roarin’ book with a down-home flavor.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A warm, witty portrait of a quietly extraordinary American life.”

—Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

BEN JONES is an actor, writer, singer, and political pundit who lives with his wife, Alma Viator, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

Extras

Chapter 1

Everything Is Purple and Gray and Covered with Soot Hey, what the hell kinda deal is this?! Everything is painted purple and gray, there is soot and cinders all over everything, and overhead gigantic silver dirigibles are flying around. There are freight trains clanging and banging in the front yard, and ships the size of skyscrapers are cruising by. Most folks I see have darker skin than mine. It smells like collards and sweat and cigars, and what’s that I hear? Off somewhere, across the water that is all around me, a bugler is playing “Taps.” I live in the country in the middle of cotton and peanuts and corn, but this is all surrounded by a city of eighty thousand people. I’m two years old and I’m asking you: What the hell kinda deal is this?!

Well, it really was that way for us. We lived in a railroad section house that looked out to a busy freight yard on the docks of Portsmouth, Virginia. But where we lived there was no neighborhood, no sidewalks, and no busy city streets; instead there were scrubby woods and plowed fields and marsh grass. You see, my father was the cigar smokin’, tobacco chewin’, whiskey drinkin’ section foreman there for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, and my mama raised four boys in that big ol’ shack.

Large railroads are divided into sections. The section foreman is responsible for the maintenance of a particular section of track. In those days, most railroads provided company houses on company land by the tracks for their employees. These were called “section houses.” Most were well constructed, though many were quite old. But all of them lacked “conveniences.”

Well, if it was primitive, my brothers and I didn’t know it. You don’t miss what you never had.

The one-lane road that ran along the tracks was called Harper Street. It was made of burnt cinders from the coal-fired steam locomotives around the rail yard. The engines produced clouds of thick black smoke all day long, and that soot settled everywhere: in the yard, on the house, and on Mama’s wash out on the clothesline.

The house seemed to have been plopped from above into a field between the freight yard and Scott’s Creek, a tidal inlet off of Hampton Roads, down where the James River meets the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic. The place was perched atop ten stacks of bricks about two feet off the ground. When Atlantic storms came on their howling visits, the old shack would sway and creak like a boat at sea, but would always settle back soft and easy on the brick piles. At one time, there were two scraggly Chinaberry trees in the yard. After a hurricane came through once, there was only one very scraggly Chinaberry tree in the yard. The rusting tin roof always hung on tight.

The only plumbing in the house was a cold-water spigot in the kitchen. Our bathroom was a “double-seater” outhouse over the creek, reached by a short bridge, and flushed by the outgoing tide. Two seats hardly did the job for my parents and me and my two older brothers, “Buck” and “Bubba.” They called me “Buster.”

We had no electricity then. Our world was lit by kerosene, and our entertainment was provided by battery-powered radios, windup Victrolas, and above all by Mama’s beautiful singing voice. Royal Purple and Silver Gray were the official colors of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. The section houses were all painted purple and gray, as were the depots, station houses, yard towers, toolsheds, roundhouses, shops, and as I could daily verify, so were the outhouses.

The paint crew appeared every five years or so to slap on another coat of gray over the sooty outer walls, trim it with purple, and seal the whole deal with a large black stencil next to the front porch marking the date of their work: 8/44.

Across the tracks, on the north side of the train yard, was the now vanished dockside community of Pinners Point. But our nearest neighbors lived in Sugar Hill, a black neighborhood just up the road on “our side of the tracks.” The men who made up my father’s “section gang” lived in Sugar Hill.

The world I came into was at war, and Hampton Roads was crucially vital to the Allied effort. After Pearl Harbor, tens of thousands of Americans poured into Norfolk and Portsmouth to work at the Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, the Norfolk Naval Base, and the Oceana Naval Air Station. The Atlantic Fleet was stationed at the Naval Base, and the world’s largest warships cruised past Pinners Point on their way to the Shipyard. The streets of Norfolk and Portsmouth were filled with young sailors in their bell bottom whites, raising a little hell before their next deployment into the North Atlantic.

German U-Boats posed a constant threat off the Virginia coast, and mammoth U.S. Navy blimps floated overhead on a constant lookout for the Nazi submarines.

Troop trains shuttled through the freight yards as military personnel shipped out of Hampton Roads for the European front. P-38 fighters, B-25 bombers, and enormous cargo planes called “flying boxcars” crisscrossed the Tidewater skies.

“Us boys” studied silhouettes of all the aircraft and considered it our duty to identify and report any suspicious shapes in the sky. I was a four-year-old plane spotter.

And on quiet evenings, just at dusk, the sound of “Taps” would waft on the salt breezes of Scott’s Creek as the bugler on the Naval Hospital grounds across the way sounded the sunset call. Then, at nine p.m. every night, the whole town would shake to the sound of the “Nine O’Clock Gun,” a traditional cannon firing by the Marines at the Shipyard.

I have a vivid early memory of a Sears and Roebuck truck delivering a new Silvertone Console Battery Radio to our place. When I mentioned that to my mama in the 1970s she seemed surprised because I was not quite three years old when that happened. But she knew the exact date of the delivery. How could she have forgotten June 6, 1944? That was D-Day.

I also have memories of the coastal blackouts. With the German subs off the coast silently watching the movement of Allied shipping, every few weeks the Civil Defense whistles would call for “all lights out!” My father would go out into the dark with his best flashlight in hand and report to his railroad position. With the shades pulled down and the lamps blown out, we would wait in the orange glow of the round dial on that Silvertone Radio for the “all clear” signal.

Chapter 2

Mama an’ ’Nim

There is an expression that you will hear in the American South and nowhere else on the planet. A person will tell you that they are going to see “Mama an’ ’Nim.” The translation for Yankees and others is that they are going home to visit family; they are going to see “Mama and them.” It comes out as one word, mama-annim. This is about mama-annim.

I took my first train ride at the age of three weeks, away from Tarboro, North Carolina, where I was born, up to Sugar Hill, which was to be home for nineteen years. Railroading is a family tradition with us. My father started working on his father’s track gang when he was thirteen, carrying water and kegs of spikes to the crew. My mother’s father, Daniel Stephens, was also an Atlantic Coast Line track man, as was one of her older brothers.

By the time my father was fifteen, he was the size of a bear and damn near as strong, and he was working on the railroad full-time, putting down crossties, swinging a twelve-pound sledge-hammer, driving spikes, laying in the rail, and building a reputation as one of the toughest steel-driving men on the Coast Line. They called him “Big Buck.” In the South, the track gangs were made up almost entirely of black men, but among those giants of strength and fortitude, my father was a legend in his time. He also started drinking cheap whiskey when he was thirteen, and I heard tales from some of the old railroad men that after the evening whistle blew, he won many a drink by wagering that he could lift a pair of boxcar wheels up off the track by himself. My old man loved his whiskey so much that he never lost that bet. Within a few years he was made foreman, and the section gang that he supervised called him “Cap’n.” They knew that he had come up the hard way, as they had, and for that he always had their loyalty.

He was old school. His father had been born in rural North Carolina before the Civil War, and when my dad was born in Nansemond County, Virginia, in 1909, little had changed since 1860. The South had reacted to its bitter defeat and the Reconstruction period by passing Jim Crow laws, establishing a strict code of “white supremacy,” and resisting any sort of social progress. Yes, slavery had been abolished, but most blacks and many whites lived in a kind of economic slavery, where the ceiling of aspiration was set very low. The war had devastated the South, and when it was over there was no Marshall Plan for rebuilding the defeated nation. As my Uncle Hamp Stephens told me, “Nobody had nothing back then.”

Daddy’s rules were simple. He was the boss, he was never wrong, when he wanted something it should be brought to him, and if he were displeased there could be psychic hell to pay. Around the house, he was King Baby, ruling with scowls and grunts. None of us dared cross him and risk his wrath. Like a lot of men of his generation, he thought the expression of tender emotions to be a great sign of weakness, and he had great difficulty communicating any sensitivity. The funny thing was we could sense his kinder feelings, even as we could sense him simultaneously trying to stifle them.

His past was a great mystery to me. And so was most of his

present. He never spoke of his childhood, his parents, his schooling, his early years on the railroad, and certainly never of his feelings toward his wife and children. There were no old letters from family. There were no stories that began “One time me and a friend of mine . . .”

He did have an old tattoo on his left forearm that simply said “M.T.” I asked him once what that meant. “Like your head,” he said. “EMM-TEE.”

He could be funny like that. He had a sense of irony and a brittle dry wit, but Daddy had a “no trespassing” sign in his head. He was the least forthcoming man I’ve ever known.

That was the sober father. The drunk father was another story. Booze was daddy’s greatest pleasure, and his favorite pastime. My father was what is called a “weekend” alcoholic. His drinking habits changed over the years, but back in the 1940s and the early 1950s the pattern was consistent. He wouldn’t touch a drop during the week, and made sure that everyone knew that. But we could tell that he couldn’t wait for that whistle to blow on Friday afternoon so he could catch up for lost time. He then drank pint after pint of Four Roses blended whiskey, and chased it down with High Rock Ginger Ale. And right before us his personality would change as inevitably as Dr. Jekyll would become Mr. Hyde.

Then, as night fell, he would often throw a temper tantrum and storm out to do some serious drinking with friends. We never knew where he was going, but we were all relieved to see him go. A brief silence would settle in while we recovered from his verbal assaults, but soon the house would hum with the sounds of the Silvertone bringing us the world. We were big on Jack Benny, Amos and Andy, Fibber McGee and Molly, The Great Gildersleeve, and Spike Jones.

Saturday morning Daddy was up and at it early. By the time us younguns were up, he was already schnockered, Mama was already completely stressed out, and we all went into the automatic bunker mentality of our survival instincts. Saturdays were the worst.

A flashback: It is a Saturday morning in 1945, maybe 1946. I am four or five years old. I follow my father to the back porch, where there is an icebox. The iceman comes by once or twice a week and checks the ice sign in our kitchen window. It is a square placard with a number on each of the square’s four sides: 10, 25, 50, 100. The number turned to the top is the amount he leaves. In summer a block of at least 50 pounds sits in the bottom of the icebox.

I cannot remember a time when my father did not chase his whiskey with High Rock Ginger Ale. But on this particular morning, after he pulls a slug from the pint of Four Roses, he lifts a large clear bottle of golden liquid and chases the whiskey with that. It is bubbly, it is foamy, it is beautiful. There is a picture of a lovely girl on the bottle; she sits in a swing. I am fascinated by this new thing. My father sees my interest and jokingly says, “You want a sip?” “Yessir!” I take the quart bottle of Miller High Life Beer and drink. My father expects me to spit it out as bitter, or at least to make a disgusted frown. I do neither. I smile and say, “That was good. Thank you, Daddy!”

That was sixty years ago, and I remember the moment and the taste with great clarity. I think I understood even then that it might have something to do with destiny.

On Sunday mornings us boys had our weekly bath. Mama would heat up some water on the woodstove and pour it in a galvanized washtub and we would take turns. Buck was the oldest, so he went first. Bubba went next and he was usually the dirtiest. Being the youngest, I went last and by the time it was my turn the water was a muddy brown. I dreaded Mama scrubbing out my filthy ears with a washrag. But that was a regular part of the drill.

From the Hardcover edition.

Everything Is Purple and Gray and Covered with Soot Hey, what the hell kinda deal is this?! Everything is painted purple and gray, there is soot and cinders all over everything, and overhead gigantic silver dirigibles are flying around. There are freight trains clanging and banging in the front yard, and ships the size of skyscrapers are cruising by. Most folks I see have darker skin than mine. It smells like collards and sweat and cigars, and what’s that I hear? Off somewhere, across the water that is all around me, a bugler is playing “Taps.” I live in the country in the middle of cotton and peanuts and corn, but this is all surrounded by a city of eighty thousand people. I’m two years old and I’m asking you: What the hell kinda deal is this?!

Well, it really was that way for us. We lived in a railroad section house that looked out to a busy freight yard on the docks of Portsmouth, Virginia. But where we lived there was no neighborhood, no sidewalks, and no busy city streets; instead there were scrubby woods and plowed fields and marsh grass. You see, my father was the cigar smokin’, tobacco chewin’, whiskey drinkin’ section foreman there for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, and my mama raised four boys in that big ol’ shack.

Large railroads are divided into sections. The section foreman is responsible for the maintenance of a particular section of track. In those days, most railroads provided company houses on company land by the tracks for their employees. These were called “section houses.” Most were well constructed, though many were quite old. But all of them lacked “conveniences.”

Well, if it was primitive, my brothers and I didn’t know it. You don’t miss what you never had.

The one-lane road that ran along the tracks was called Harper Street. It was made of burnt cinders from the coal-fired steam locomotives around the rail yard. The engines produced clouds of thick black smoke all day long, and that soot settled everywhere: in the yard, on the house, and on Mama’s wash out on the clothesline.

The house seemed to have been plopped from above into a field between the freight yard and Scott’s Creek, a tidal inlet off of Hampton Roads, down where the James River meets the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic. The place was perched atop ten stacks of bricks about two feet off the ground. When Atlantic storms came on their howling visits, the old shack would sway and creak like a boat at sea, but would always settle back soft and easy on the brick piles. At one time, there were two scraggly Chinaberry trees in the yard. After a hurricane came through once, there was only one very scraggly Chinaberry tree in the yard. The rusting tin roof always hung on tight.

The only plumbing in the house was a cold-water spigot in the kitchen. Our bathroom was a “double-seater” outhouse over the creek, reached by a short bridge, and flushed by the outgoing tide. Two seats hardly did the job for my parents and me and my two older brothers, “Buck” and “Bubba.” They called me “Buster.”

We had no electricity then. Our world was lit by kerosene, and our entertainment was provided by battery-powered radios, windup Victrolas, and above all by Mama’s beautiful singing voice. Royal Purple and Silver Gray were the official colors of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. The section houses were all painted purple and gray, as were the depots, station houses, yard towers, toolsheds, roundhouses, shops, and as I could daily verify, so were the outhouses.

The paint crew appeared every five years or so to slap on another coat of gray over the sooty outer walls, trim it with purple, and seal the whole deal with a large black stencil next to the front porch marking the date of their work: 8/44.

Across the tracks, on the north side of the train yard, was the now vanished dockside community of Pinners Point. But our nearest neighbors lived in Sugar Hill, a black neighborhood just up the road on “our side of the tracks.” The men who made up my father’s “section gang” lived in Sugar Hill.

The world I came into was at war, and Hampton Roads was crucially vital to the Allied effort. After Pearl Harbor, tens of thousands of Americans poured into Norfolk and Portsmouth to work at the Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, the Norfolk Naval Base, and the Oceana Naval Air Station. The Atlantic Fleet was stationed at the Naval Base, and the world’s largest warships cruised past Pinners Point on their way to the Shipyard. The streets of Norfolk and Portsmouth were filled with young sailors in their bell bottom whites, raising a little hell before their next deployment into the North Atlantic.

German U-Boats posed a constant threat off the Virginia coast, and mammoth U.S. Navy blimps floated overhead on a constant lookout for the Nazi submarines.

Troop trains shuttled through the freight yards as military personnel shipped out of Hampton Roads for the European front. P-38 fighters, B-25 bombers, and enormous cargo planes called “flying boxcars” crisscrossed the Tidewater skies.

“Us boys” studied silhouettes of all the aircraft and considered it our duty to identify and report any suspicious shapes in the sky. I was a four-year-old plane spotter.

And on quiet evenings, just at dusk, the sound of “Taps” would waft on the salt breezes of Scott’s Creek as the bugler on the Naval Hospital grounds across the way sounded the sunset call. Then, at nine p.m. every night, the whole town would shake to the sound of the “Nine O’Clock Gun,” a traditional cannon firing by the Marines at the Shipyard.

I have a vivid early memory of a Sears and Roebuck truck delivering a new Silvertone Console Battery Radio to our place. When I mentioned that to my mama in the 1970s she seemed surprised because I was not quite three years old when that happened. But she knew the exact date of the delivery. How could she have forgotten June 6, 1944? That was D-Day.

I also have memories of the coastal blackouts. With the German subs off the coast silently watching the movement of Allied shipping, every few weeks the Civil Defense whistles would call for “all lights out!” My father would go out into the dark with his best flashlight in hand and report to his railroad position. With the shades pulled down and the lamps blown out, we would wait in the orange glow of the round dial on that Silvertone Radio for the “all clear” signal.

Chapter 2

Mama an’ ’Nim

There is an expression that you will hear in the American South and nowhere else on the planet. A person will tell you that they are going to see “Mama an’ ’Nim.” The translation for Yankees and others is that they are going home to visit family; they are going to see “Mama and them.” It comes out as one word, mama-annim. This is about mama-annim.

I took my first train ride at the age of three weeks, away from Tarboro, North Carolina, where I was born, up to Sugar Hill, which was to be home for nineteen years. Railroading is a family tradition with us. My father started working on his father’s track gang when he was thirteen, carrying water and kegs of spikes to the crew. My mother’s father, Daniel Stephens, was also an Atlantic Coast Line track man, as was one of her older brothers.

By the time my father was fifteen, he was the size of a bear and damn near as strong, and he was working on the railroad full-time, putting down crossties, swinging a twelve-pound sledge-hammer, driving spikes, laying in the rail, and building a reputation as one of the toughest steel-driving men on the Coast Line. They called him “Big Buck.” In the South, the track gangs were made up almost entirely of black men, but among those giants of strength and fortitude, my father was a legend in his time. He also started drinking cheap whiskey when he was thirteen, and I heard tales from some of the old railroad men that after the evening whistle blew, he won many a drink by wagering that he could lift a pair of boxcar wheels up off the track by himself. My old man loved his whiskey so much that he never lost that bet. Within a few years he was made foreman, and the section gang that he supervised called him “Cap’n.” They knew that he had come up the hard way, as they had, and for that he always had their loyalty.

He was old school. His father had been born in rural North Carolina before the Civil War, and when my dad was born in Nansemond County, Virginia, in 1909, little had changed since 1860. The South had reacted to its bitter defeat and the Reconstruction period by passing Jim Crow laws, establishing a strict code of “white supremacy,” and resisting any sort of social progress. Yes, slavery had been abolished, but most blacks and many whites lived in a kind of economic slavery, where the ceiling of aspiration was set very low. The war had devastated the South, and when it was over there was no Marshall Plan for rebuilding the defeated nation. As my Uncle Hamp Stephens told me, “Nobody had nothing back then.”

Daddy’s rules were simple. He was the boss, he was never wrong, when he wanted something it should be brought to him, and if he were displeased there could be psychic hell to pay. Around the house, he was King Baby, ruling with scowls and grunts. None of us dared cross him and risk his wrath. Like a lot of men of his generation, he thought the expression of tender emotions to be a great sign of weakness, and he had great difficulty communicating any sensitivity. The funny thing was we could sense his kinder feelings, even as we could sense him simultaneously trying to stifle them.

His past was a great mystery to me. And so was most of his

present. He never spoke of his childhood, his parents, his schooling, his early years on the railroad, and certainly never of his feelings toward his wife and children. There were no old letters from family. There were no stories that began “One time me and a friend of mine . . .”

He did have an old tattoo on his left forearm that simply said “M.T.” I asked him once what that meant. “Like your head,” he said. “EMM-TEE.”

He could be funny like that. He had a sense of irony and a brittle dry wit, but Daddy had a “no trespassing” sign in his head. He was the least forthcoming man I’ve ever known.

That was the sober father. The drunk father was another story. Booze was daddy’s greatest pleasure, and his favorite pastime. My father was what is called a “weekend” alcoholic. His drinking habits changed over the years, but back in the 1940s and the early 1950s the pattern was consistent. He wouldn’t touch a drop during the week, and made sure that everyone knew that. But we could tell that he couldn’t wait for that whistle to blow on Friday afternoon so he could catch up for lost time. He then drank pint after pint of Four Roses blended whiskey, and chased it down with High Rock Ginger Ale. And right before us his personality would change as inevitably as Dr. Jekyll would become Mr. Hyde.

Then, as night fell, he would often throw a temper tantrum and storm out to do some serious drinking with friends. We never knew where he was going, but we were all relieved to see him go. A brief silence would settle in while we recovered from his verbal assaults, but soon the house would hum with the sounds of the Silvertone bringing us the world. We were big on Jack Benny, Amos and Andy, Fibber McGee and Molly, The Great Gildersleeve, and Spike Jones.

Saturday morning Daddy was up and at it early. By the time us younguns were up, he was already schnockered, Mama was already completely stressed out, and we all went into the automatic bunker mentality of our survival instincts. Saturdays were the worst.

A flashback: It is a Saturday morning in 1945, maybe 1946. I am four or five years old. I follow my father to the back porch, where there is an icebox. The iceman comes by once or twice a week and checks the ice sign in our kitchen window. It is a square placard with a number on each of the square’s four sides: 10, 25, 50, 100. The number turned to the top is the amount he leaves. In summer a block of at least 50 pounds sits in the bottom of the icebox.

I cannot remember a time when my father did not chase his whiskey with High Rock Ginger Ale. But on this particular morning, after he pulls a slug from the pint of Four Roses, he lifts a large clear bottle of golden liquid and chases the whiskey with that. It is bubbly, it is foamy, it is beautiful. There is a picture of a lovely girl on the bottle; she sits in a swing. I am fascinated by this new thing. My father sees my interest and jokingly says, “You want a sip?” “Yessir!” I take the quart bottle of Miller High Life Beer and drink. My father expects me to spit it out as bitter, or at least to make a disgusted frown. I do neither. I smile and say, “That was good. Thank you, Daddy!”

That was sixty years ago, and I remember the moment and the taste with great clarity. I think I understood even then that it might have something to do with destiny.

On Sunday mornings us boys had our weekly bath. Mama would heat up some water on the woodstove and pour it in a galvanized washtub and we would take turns. Buck was the oldest, so he went first. Bubba went next and he was usually the dirtiest. Being the youngest, I went last and by the time it was my turn the water was a muddy brown. I dreaded Mama scrubbing out my filthy ears with a washrag. But that was a regular part of the drill.

From the Hardcover edition.