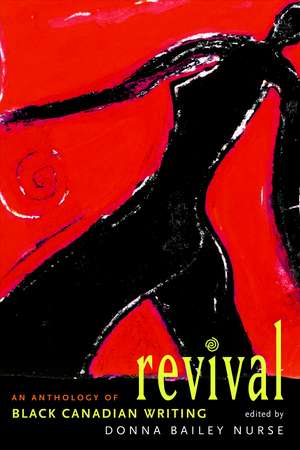

Revival: An Anthology of Black Canadian Writing

Editat de Donna Bailey Nurseen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2006

Drawing on fiction, poetry, and memoir, this anthology brings together an impressively varied selection of outstanding work by both well-known writers and new voices. Donna Bailey Nurse’s lively and invaluable introduction deftly explores the various themes and motifs that define and illuminate the meaning of being black, while tracing the evolution of this influential literature through colonialism, post-colonialism, and decolonization.

This engaging collection celebrates a body of writing that holds an increasingly visible and important place within Canadian literature, and stands among the finest literary anthologies in the country.

Preț: 128.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.62€ • 25.61$ • 20.32£

24.62€ • 25.61$ • 20.32£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771067631

ISBN-10: 0771067631

Pagini: 383

Dimensiuni: 149 x 216 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.6 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771067631

Pagini: 383

Dimensiuni: 149 x 216 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.6 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Donna Bailey Nurse is a literary journalist, a lecturer, a critic for BookTelevision, and the author of What’s a Black Critic to Do?: Interviews, Profiles and Reviews of Black Writers. She is a frequent book reviewer for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, the Toronto Star, and the Montreal Gazette, and her articles exploring race and culture have appeared in these publications as well as in Maclean’s, Publishers Weekly, the Washington Post, and the Boston Globe. She lives in Toronto.

Extras

Introduction

I grew up on the elbow of land between Lake Ontario and Frenchman’s Bay, surrounded by Pickering’s towering blue spruce and pungent wetlands. We played in fields of ruined farmhouses during summers as green and perpetual as the Caribbean Sea. In winter, the sky was white and still, like the land itself. The schoolyard was a snowy desert, and bundled thick as snowmen, my sister and I sank through to our knees. At home, Miss Iris, our Jamaican grandma, fixed us Ovaltine, then sat with her sisters in the back room, mending clothes and talking “big people business,” while a pot of pigs’ tail sputtered on the stove. I curled up on the sofa with Lucy Maud and Laura Ingalls and wondered, What did Katy do? But outside, brown skin was harder to negotiate than snowdrifts. You had to play dumb. A little girl asked: “Are you a ghost?” But she was the one who was white. I was a little girl too, but I knew that much. Skin colour was no big deal, until suddenly, without warning, it was. The ambush comment or question, the backhanded compliment, the acts of emotional violence meant to remind me of what I was not, which was not white and not from here. They were right and wrong. I’m not white but I am from here. Black and Canadian: equal parts race and place.

Literature has been the means through which I have learned to understand who I am and who I might be — as a human being, as a woman, and as a person of African descent. Over the years, my experience reading, studying, and writing about black Canadian letters, most recently as a literary critic, has served to reaffirm my identity as a Canadian. I became a critic of black Canadian literature largely because I wanted to engage others in a dialogue about black writing in this country, and it was important to me that the dialogue be led by somebody who was black. This literature is at the forefront of public and artistic spaces grappling with what it means to be of this race and of this place, and as such, it represents a crucial voice in the necessary conversation about the black experience in Canada.

Revival constitutes a conversation about the relevance of black Canadian writing like no other, and celebrates the coming of age of a black Canadian literature. It builds proudly upon previous anthologies that confirmed the existence of a growing body of black Canadian writing, including Lorris Elliott’s Other Voices: Writings by Blacks in Canada (1985), Cyril Dabydeen’s A Shapely Fire: Changing the Literary Landscape (1987), Ayanna Black’s Voices: Canadian Writers of African Descent (1992), and George Elliott Clarke’s Eyeing the North Star: Directions in African-Canadian Literature (1997).

Eyeing the North Star marked a pivotal moment in the development of a black Canadian literature. It reaffirmed the importance of such established figures as Austin Clarke, M. NourbeSe Philip, and Claire Harris, while showcasing newer voices, including Lawrence Hill, André Alexis, and David N. Odhiambo. In his introduction, George Elliott Clarke addressed the characteristics of a black Canadian aesthetic; he defined it as “international” in its “concern for African people everywhere,” in its “solidarity with third world peoples,” and in its “utilization of a diverse range of rhetorical styles.” Agreeing with writer Liz Cromwell, Clarke describes the literature as concerned with a history of forced relocation, coerced labour, and the struggle against discrimination.

The publication of Clarke’s anthology in 1997 was also significant for its timing and as an indication of the growing interest in black Canadian writing. Beginning in the mid-nineties, the literature began to accumulate critical mass. The ensuing decade would see the publication of award-winning works of fiction (including André Alexis’s Childhood, Austin Clarke’s The Polished Hoe, and Nalo Hopkinson’s Brown Girl in the Ring), memoir (Rachel Manley’s Drumblair and Ken Wiwa’s In the Shadow of a Saint); drama (Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet), and poetry (Dionne Brand’s Land to Light On).

Black Canadian writing has come of age over the last decade, and the time now seems right for a reconsideration of this increasingly influential literature. With twenty-nine contributors and over fifty pieces drawn from works of fiction, poetry, and memoir, Revival provides a varied overview of contemporary black Canadian literature. Previous anthologies have confirmed the diversity of black Canada’s literary voices, and Revival acknowledges this multiplicity, with contributors originally from Africa and the Caribbean, as well as several born in Canada.

The astonishing gifts of the newer voices in the anthology merit extra mention. Poets Wayde Compton and Shane Book and novelists Esi Edugyan and Kim Barry Brunhuber assimilate and alchemize a wealth of literary influences to produce original and distinct individual styles. In addition, Revival is the first Canadian anthology to feature Okey Chigbo, whose work has appeared in Chinua Achebe and Lynn Innes’s influential Contemporary African Short Stories.

For me, the seeds of contemporary black Canadian literature were sown in the mid-sixties with the novels of Austin Clarke. Clarke’s early success had partly to do with the time and place in which he launched his career. Beginning in the mid-fifties, when Clarke arrived in Canada to attend the University of Toronto, the Canadian government began opening the doors to Caribbean immigrants through student visas and through programs such as the Caribbean Domestic Scheme, which saw thousands of women enter the country to work as nannies and maids. At the same time, the civil rights movement in the United States, with its attendant turmoil, attuned Canadians to issues of race and racism. Just as important was Toronto’s burgeoning creative scene. Clarke belonged to a number of artistic circles, among them a group of Toronto writers that included Barry Callaghan and Margaret Atwood, who were nurturing a vision of a homegrown literature. The proximity of major publishing houses also meant he had access to people who might publish his work.

I grew up on the elbow of land between Lake Ontario and Frenchman’s Bay, surrounded by Pickering’s towering blue spruce and pungent wetlands. We played in fields of ruined farmhouses during summers as green and perpetual as the Caribbean Sea. In winter, the sky was white and still, like the land itself. The schoolyard was a snowy desert, and bundled thick as snowmen, my sister and I sank through to our knees. At home, Miss Iris, our Jamaican grandma, fixed us Ovaltine, then sat with her sisters in the back room, mending clothes and talking “big people business,” while a pot of pigs’ tail sputtered on the stove. I curled up on the sofa with Lucy Maud and Laura Ingalls and wondered, What did Katy do? But outside, brown skin was harder to negotiate than snowdrifts. You had to play dumb. A little girl asked: “Are you a ghost?” But she was the one who was white. I was a little girl too, but I knew that much. Skin colour was no big deal, until suddenly, without warning, it was. The ambush comment or question, the backhanded compliment, the acts of emotional violence meant to remind me of what I was not, which was not white and not from here. They were right and wrong. I’m not white but I am from here. Black and Canadian: equal parts race and place.

Literature has been the means through which I have learned to understand who I am and who I might be — as a human being, as a woman, and as a person of African descent. Over the years, my experience reading, studying, and writing about black Canadian letters, most recently as a literary critic, has served to reaffirm my identity as a Canadian. I became a critic of black Canadian literature largely because I wanted to engage others in a dialogue about black writing in this country, and it was important to me that the dialogue be led by somebody who was black. This literature is at the forefront of public and artistic spaces grappling with what it means to be of this race and of this place, and as such, it represents a crucial voice in the necessary conversation about the black experience in Canada.

Revival constitutes a conversation about the relevance of black Canadian writing like no other, and celebrates the coming of age of a black Canadian literature. It builds proudly upon previous anthologies that confirmed the existence of a growing body of black Canadian writing, including Lorris Elliott’s Other Voices: Writings by Blacks in Canada (1985), Cyril Dabydeen’s A Shapely Fire: Changing the Literary Landscape (1987), Ayanna Black’s Voices: Canadian Writers of African Descent (1992), and George Elliott Clarke’s Eyeing the North Star: Directions in African-Canadian Literature (1997).

Eyeing the North Star marked a pivotal moment in the development of a black Canadian literature. It reaffirmed the importance of such established figures as Austin Clarke, M. NourbeSe Philip, and Claire Harris, while showcasing newer voices, including Lawrence Hill, André Alexis, and David N. Odhiambo. In his introduction, George Elliott Clarke addressed the characteristics of a black Canadian aesthetic; he defined it as “international” in its “concern for African people everywhere,” in its “solidarity with third world peoples,” and in its “utilization of a diverse range of rhetorical styles.” Agreeing with writer Liz Cromwell, Clarke describes the literature as concerned with a history of forced relocation, coerced labour, and the struggle against discrimination.

The publication of Clarke’s anthology in 1997 was also significant for its timing and as an indication of the growing interest in black Canadian writing. Beginning in the mid-nineties, the literature began to accumulate critical mass. The ensuing decade would see the publication of award-winning works of fiction (including André Alexis’s Childhood, Austin Clarke’s The Polished Hoe, and Nalo Hopkinson’s Brown Girl in the Ring), memoir (Rachel Manley’s Drumblair and Ken Wiwa’s In the Shadow of a Saint); drama (Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet), and poetry (Dionne Brand’s Land to Light On).

Black Canadian writing has come of age over the last decade, and the time now seems right for a reconsideration of this increasingly influential literature. With twenty-nine contributors and over fifty pieces drawn from works of fiction, poetry, and memoir, Revival provides a varied overview of contemporary black Canadian literature. Previous anthologies have confirmed the diversity of black Canada’s literary voices, and Revival acknowledges this multiplicity, with contributors originally from Africa and the Caribbean, as well as several born in Canada.

The astonishing gifts of the newer voices in the anthology merit extra mention. Poets Wayde Compton and Shane Book and novelists Esi Edugyan and Kim Barry Brunhuber assimilate and alchemize a wealth of literary influences to produce original and distinct individual styles. In addition, Revival is the first Canadian anthology to feature Okey Chigbo, whose work has appeared in Chinua Achebe and Lynn Innes’s influential Contemporary African Short Stories.

For me, the seeds of contemporary black Canadian literature were sown in the mid-sixties with the novels of Austin Clarke. Clarke’s early success had partly to do with the time and place in which he launched his career. Beginning in the mid-fifties, when Clarke arrived in Canada to attend the University of Toronto, the Canadian government began opening the doors to Caribbean immigrants through student visas and through programs such as the Caribbean Domestic Scheme, which saw thousands of women enter the country to work as nannies and maids. At the same time, the civil rights movement in the United States, with its attendant turmoil, attuned Canadians to issues of race and racism. Just as important was Toronto’s burgeoning creative scene. Clarke belonged to a number of artistic circles, among them a group of Toronto writers that included Barry Callaghan and Margaret Atwood, who were nurturing a vision of a homegrown literature. The proximity of major publishing houses also meant he had access to people who might publish his work.

Cuprins

Introduction by Donna Bailey Nurse

Claire Harris (b. 1937)

Untitled

Travelling to Find a Remedy

Towards the Colour of Summer

Kay in Summer

Émile Ollivier (1940-2002)

from Mother Solitude

Olive Senior (b. 1941)

Do Angels Wear Brassieres?

Meditation on Yellow

The Pull of Birds

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Blackbird

Pamela Mordecai (b. 1942)

Poems Grow

Convent Girl

The Angel in the House

Althea Prince (b. 1945)

from Loving This Man

Lorna Goodison (b. 1947)

What We Carried That Carried Us

Never Expect

Questions for Marcus Mosiah Garvey

from From Harvey River: A Memoir

Rachel Manley (b. 1947)

from Drumblair: Memories of a Jamaican Childhood

M. NourbeSe Philip (b. 1947)

Salmon Courage

Meditations on the Declension of Beauty by the Girl with the Flying Cheek-bones

The Catechist

Cashew #4

H. Nigel Thomas (b. 1947)

How Loud Can the Village Cock Crow?

Honor Ford-Smith (b. 1951)

from My Mother’s Last Dance

Dany Laferrière (b. 1953)

from How to Make Love to a Negro

from An Aroma of Coffee

Okey Chigbo (b. 1955)

The Housegirl

Makeda Silvera (b. 1955)

from The Heart Does Not Bend

André Alexis (b. 1957)

from Childhood

Afua Cooper (b. 1957)

On the Way to Sunday School

Memories Have Tongue

Christopher Columbus

Lawrence Hill (b. 1957)

from Any Known Blood

Tessa McWatt (b. 1959)

from Dragons Cry

George Elliott Clarke (b. 1960)

The Wisdom of Shelley

King Bee Blues

from George & Rue

Nalo Hopkinson (b. 1960)

from Midnight Robber

David N. Odhiambo (b. 1965)

from Kipligat’s Chance

Suzette Mayr (b. 1967)

from The Widows

Robert Edison Sandiford (b. 1968)

from Sand for Snow: A Caribbean-Canadian Chronicle

Ken Wiwa (b. 1968)

from the Preface to In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son’s Journey to Understand His Father’s Legacy

Shane Book (b. 1970)

HNIC

The One

Flagelliform: #9

Flagelliform: Fact

Flagelliform: Ayahuasca

Motion (b. 1970)

Girl

I-Land

Wayde Compton (b. 1972)

Legba, Landed

Declaration of the Halfrican Nation

To Poitier

Kim Barry Brunhuber (b. 1973)

from Kameleon Man

Jemeni (b. 1974)

The Black Speaker

Esi Edugyan (b. 1977)

from The Second Life of Samuel Tyne

About the Authors

Suggested Reading

A Note on the Text and Acknowledgements

Claire Harris (b. 1937)

Untitled

Travelling to Find a Remedy

Towards the Colour of Summer

Kay in Summer

Émile Ollivier (1940-2002)

from Mother Solitude

Olive Senior (b. 1941)

Do Angels Wear Brassieres?

Meditation on Yellow

The Pull of Birds

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Blackbird

Pamela Mordecai (b. 1942)

Poems Grow

Convent Girl

The Angel in the House

Althea Prince (b. 1945)

from Loving This Man

Lorna Goodison (b. 1947)

What We Carried That Carried Us

Never Expect

Questions for Marcus Mosiah Garvey

from From Harvey River: A Memoir

Rachel Manley (b. 1947)

from Drumblair: Memories of a Jamaican Childhood

M. NourbeSe Philip (b. 1947)

Salmon Courage

Meditations on the Declension of Beauty by the Girl with the Flying Cheek-bones

The Catechist

Cashew #4

H. Nigel Thomas (b. 1947)

How Loud Can the Village Cock Crow?

Honor Ford-Smith (b. 1951)

from My Mother’s Last Dance

Dany Laferrière (b. 1953)

from How to Make Love to a Negro

from An Aroma of Coffee

Okey Chigbo (b. 1955)

The Housegirl

Makeda Silvera (b. 1955)

from The Heart Does Not Bend

André Alexis (b. 1957)

from Childhood

Afua Cooper (b. 1957)

On the Way to Sunday School

Memories Have Tongue

Christopher Columbus

Lawrence Hill (b. 1957)

from Any Known Blood

Tessa McWatt (b. 1959)

from Dragons Cry

George Elliott Clarke (b. 1960)

The Wisdom of Shelley

King Bee Blues

from George & Rue

Nalo Hopkinson (b. 1960)

from Midnight Robber

David N. Odhiambo (b. 1965)

from Kipligat’s Chance

Suzette Mayr (b. 1967)

from The Widows

Robert Edison Sandiford (b. 1968)

from Sand for Snow: A Caribbean-Canadian Chronicle

Ken Wiwa (b. 1968)

from the Preface to In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son’s Journey to Understand His Father’s Legacy

Shane Book (b. 1970)

HNIC

The One

Flagelliform: #9

Flagelliform: Fact

Flagelliform: Ayahuasca

Motion (b. 1970)

Girl

I-Land

Wayde Compton (b. 1972)

Legba, Landed

Declaration of the Halfrican Nation

To Poitier

Kim Barry Brunhuber (b. 1973)

from Kameleon Man

Jemeni (b. 1974)

The Black Speaker

Esi Edugyan (b. 1977)

from The Second Life of Samuel Tyne

About the Authors

Suggested Reading

A Note on the Text and Acknowledgements