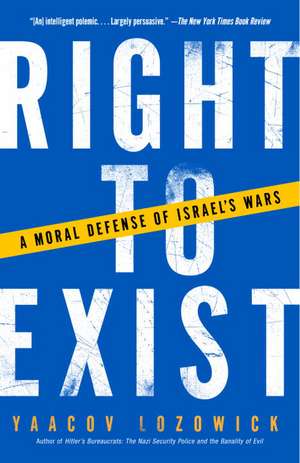

Right to Exist: A Moral Defense of Israel's Wars

Autor Yaacov Lozowicken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2004

Covering Israel's struggle for existence from the British occupation and the UN’s partition of Palestine, to the dashed hopes of the Oslo Accords and the second intifada, Yaacov Lozowick trains an enlightening, forthright eye on Israel’s strengths and failures. A lifelong liberal and peace activist, he explores Israel’s national and regional political, social, and moral obligations as well as its right to secure its borders and repel attacks both philosophical and military. Combining rich historical perspective and passionate conviction, Right to Exist sets forth the agenda of a people and a nation, and elegantly articulates Israel’s entitlement to a peaceful coexistence with its surrounding Arab neighbors and a future of security and pride.

Preț: 96.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.55€ • 19.42$ • 15.38£

18.55€ • 19.42$ • 15.38£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400032433

ISBN-10: 1400032431

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400032431

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Yaacov Lozowick is the director of the archives at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Museum, and the author of Hitler’s Bureaucrats: The Nazi Security Police and the Banality of Evil.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

Why I Voted for Sharon

The war against the Jews goes on. Jewish children are shot in their beds, and the shooters are celebrated as heroes. Jewish teenagers are blown up, and the mothers of their murderers exult. Elderly Jews are burned to death, and the killers gloat on their Web sites. And across the Arab world from Pakistan to Morocco, hundreds of millions have nothing better to do than to chant for the death of the Jews. If there was one thing to be learned from the twentieth century, it is that when people consistently say that they want the Jews dead, they may actually mean it. And when the rest of the world looks away or pretends not to hear, the killers take silence for acquiescence, acquiescence for concurrence, and concurrence for support.

Yet in our generation the Jews are quite capable of defending themselves, and that confuses the issue. The irrationality of wishing the Jews gone can hide—just barely—behind political considerations: the Jews must change before one can live with them. The immorality of passive support for the killers can hide—almost plausibly—behind censure of the way the Jews wield power: the Jews have brought their enemies’ ire upon themselves. Worst of all, the resolve of the Jews never to succumb can be whittled away by their own doubts about the wisdom of surviving by the sword and by their hopes of buying acceptance with political gambles: if only we were more benign and accommodating, our enemies would accept us.

The Jews cannot decide for the Arabs to accept Israel’s right to exist. They cannot decide for Israel’s Western detractors to accept the morality of the choices she makes. But Israel can and must do her utmost to ensure that her choices are moral and wise; when they’re not, they must be corrected. Jews care deeply about morality and always have; this has been a source of their strength in the face of enduring adversity. Since the adversity continues unabated, the strength that comes from being moral is as essential as ever.

My initial understanding of Zionism, while childish, was shared by most adults I knew. It had a good side, the Israelis, and a bad side, the Arabs, and they were so bad that their motives seemed almost inexplicable. The Arabs kept trying to destroy Israel, but Israel, partly by virtue of her moral methods of waging war, repeatedly rebuffed the heinous Arab attacks. The events of spring 1967—bombastic Arab speeches about destroying Israel, total international ineptitude in stopping them, if not even acquiescence, and then the seemingly miraculous Israeli deliverance and victory—these were the formative events of my childhood.

My arrogant complacency took its first blow on the gray afternoon of February 21, 1973, when our fighter pilots shot down a civilian Libyan airliner that had strayed into Israeli airspace over the Sinai. I was appalled by the deaths of everyone aboard and horrified by the total lack of remorse exhibited by the head of the army and the two civilians above him, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister Golda Meir. The plane had no reason to be there, they said. It had flown over a military installation. It could have been spying. There was no way to know—so they had ordered it shot down.

I was a teenager at the time, and in the first political act of my life I faced my peers with the demand that they agree that while Zionism was still fine, these particular Zionists must go. Almost no one agreed.

From 1975 I spent three years in the armored corps. The army I was in was still reeling from the ferocity of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, in which people I knew had been killed; we spent most of our time in the Sinai desert, training to stop and rout another Egyptian attack, should it come. To listen to Israel’s critics today, we were already a decade into the brutal occupation of the Palestinians, but neither I nor anyone I knew had any military encounters with occupied Palestinians. We served on the borders and faced Arab armies or Palestinian forces in Lebanon; the Palestinians under our occupation went to work in Israel, and while undoubtedly disliking us intensely, they did very little that called for brutal oppression. On vacations we would roam freely wherever we wished, at times taking Palestinian buses between Palestinian towns. One image stands out: eight or nine of us standing in a Palestinian town and Avi Greenwald cracking jokes in Yiddish, to the tremendous amusement of the young Palestinians grouped around us. Avi was killed a few years later, fighting the Syrians; I have no doubt that some of those young Palestinians were later killed fighting us. That simple scene is hard to conceive of today.

A few years later, out of the army and at university, I took to reading history, particularly the history of the Jewish state. The good guys vs. bad guys version of the story on which I had been raised lost its appeal; the story of Zionism acquired darker hues, and Arab rejectionism became less inexplicable. They hadn’t asked us to come to their part of the world; the simplistic version of Zionism as a national movement that never did anything wrong, so I learned, was not the full story. As time went on, it seemed to me that saving the soul of the Zionist project required—indeed demanded—that Israel address the Arab predicament. That we reach a mutual accommodation that would address the basic needs not only of the Jews, but of their neighbors, especially the Palestinians. The Egyptian case was a shining example that this could happen.

In 1978, a trio of American, Egyptian, and Israeli leaders cloistered themselves at Camp David; the result was a treaty that has withstood some pretty severe tests. Those were heady days. Upon his return, Prime Minister Menachem Begin was greeted at the airport by thousands of cheering demonstrators; a representative of the Peace Now movement announced: “We didn’t vote for Begin, but as he has risen to the historic moment, we’ll marshal all our forces to support him.” The image was in black and white: color TV came to Israel only a few years later. The physical sensation was unforgettable. I was overcome by tears of emotion at the prospect of life in a country not at war—“a normal country.”

Though not actively interested in politics in those days, I was inclined to support whoever was willing to seek negotiating partners for peace, even if this meant handing over additional chunks of the territory we’d been holding since 1967. This put me to the left of the political center, since most people didn’t see any additional partners to discuss peace with, beyond the Egyptians.

Any final wavering about my political position was beaten out of me in 1982, when we went to war in Lebanon. The Lebanese war was Israel’s fifth since 1947, but it was the first war that many of us wondered about even before it had started. For one thing, it didn’t seem an unavoidable war of self-defense as the others had been. For another, it was brewing just as we were completing our evacuation of the Sinai as part of the agreement with Egypt, a peace that as yet showed no sign of spreading to the rest of the Arab world. The final stages of that agreement included the dismantling of settlements in Sinai set up after the Six-Day War and was presided over by an unlikely duo of hawks, Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon, his minister of defense. Sharon, already nicknamed “the Bulldozer” for his ability to get things done, quite literally bulldozed the settlements lest the settlers return, he said—or lest the Egyptians try to use them, some of us speculated. Then, within two months, these peacemakers took us to war.

The plan seemed straightforward enough. We were going to push the brigades and artillery of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) away from our northern border, whence they had been shelling and infiltrating northern Israel for several years; the war would be a limited affair, not very costly in blood and quickly over. We wouldn’t tangle with the Syrians unless they chose to tangle with us, and the whole thing had the fine title Operation Peace for Galilee.

Yet within a few days, doubts began to gnaw at us. Rumors coming from units facing the Syrians suggested that some of the provocations had been ours, not theirs. The government had assured us that the goal was to reach a line forty kilometers north of our border, but we were obviously not stopping at that line—nor was the operation over within a few days, or a week, or a month. About then, we had our first taste of a totally new phenomenon: A group of reserve officers, freshly demobilized from active duty at the front, announced to an incredulous nation that they thought this was a stupid war.

As weeks turned into months, the pictures got worse. Every evening we would watch on television as our aircraft pounded Beirut: there were high-rise buildings there. How can you bomb them without hitting the wrong people? The wife of a lieutenant colonel whom I had known in high school published his letters of dissent in Haaretz, our left-leaning highbrow newspaper; he was abruptly thrown out of the army. Then the rebellious reservists were joined by a career officer, a full colonel who resigned rather than lead his troops into house-to-house combat in Beirut. Even cabinet ministers began to mutter that this was not the operation they had authorized and refused to countenance any further advances.

Begin, meanwhile, seemed increasingly out of touch. Visiting some crack troops who had just taken a very tough PLO position in an old crusader fortress called Beaufort, where they had lost their commanding officer, he inquired if the enemy had used “firing machines”—an archaic word for machine guns. Then he compared Yasser Arafat in his bunker to Hitler, prompting author Amos Oz to publish his famous article, “Hitler Is Dead, Mr. Prime Minister!” Soon he would visibly start to wither, eventually fading from the public eye and then out of office entirely. For better or worse, we were left with one major villain, Ariel Sharon, minister of defense and the architect of the entire campaign.

People like myself decidedly didn’t like Sharon even before 1982. Though he had fought heroically in the War of Independence and was an acknowledged tactical genius, there was something brutal about him. He set goals and reached them, no matter what the cost in human lives, whether in the Arab town of Kibiya in 1953, the Mitla Pass battle of 1956, or the subduing of the Gaza refugee camps in 1970. Even his brilliant turning of the tide in the Sinai in 1973 was rumored to have been the result of crass insubordination at a human cost that was not necessary. Perhaps most disturbing of all, he was completely free of any doubts, always certain that he was right and everyone else wrong, and since leaving the army and entering politics after the war of 1973, he had been a hard-line cabinet minister, the chief architect of the new settlements springing up throughout the West Bank. The political Right loved him, and the Left hated him, for the same reason: He represented Zionism’s transformation of weak but moral Jews into immoral power users.

At the end of September 1982, Lebanese president-elect Bashir Gemayel, perceived as pro-Israeli, was assassinated by Syrian proxies. For reasons still unclear, the Israelis allowed units of Gemayel’s paramilitaries into the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps near Beirut, where they massacred hundreds of defenseless Palestinian civilians. For a moment of panic we feared that our own men were implicated, but even when we understood that the murderers were Arabs, we were still horrified that we had somehow become allied to such thugs. The growing sense of unease and rejection that had been building all summer exploded in a nauseating attack of guilt and an acute sense of moral defilement. How could anyone have dared to drag us so incredibly low? With a sense of doom, we turned our fury on the man who epitomized the whole morass: Ariel Sharon.

There was a tidal wave of demonstrations, culminating in what is still referred to as the “Rally of the 400,000,” although the square where it took place couldn’t contain more than half that number. But even two hundred thousand people made up a full 5 percent of the population, equivalent to having fourteen million Americans at one rally. The government bowed to the pressure and appointed a commission of inquiry headed by Chief Justice Yitzhak Kahan. Then began a very tense period of waiting.

The winter of 1983 was unusually bleak. The misadventure in Lebanon was proving a quagmire akin to the American experience in Vietnam. The populace was sharply divided: the enthusiastic supporters of Menachem Begin, until recently a charismatic leader and hypnotic orator, had no patience for what they saw as spinelessness in the face of a hostile Arab world; we in the opposition were deeply mortified by what seemed our encroaching moral integration into the surrounding Middle East. Then in February the Kahan Commission recommended that Sharon leave the Ministry of Defense for his failure to foresee the danger in allowing the Phalange forces into those camps. What remained was for the government to accept the recommendations.

The tension in the air was palpable. Walking down Ben Yehuda Street in the center of Jerusalem, I saw an ugly crowd of gesticulating and cursing men. Edging my way in, I recognized the man at their epicenter: we were reservists together. Short, dark, and of Iraqi descent, Nathan did not at all resemble your stereotypical light-skinned academic peace activist. But he was proudly and furiously holding his own, damning Sharon and his failures and drawing the holy wrath of the surrounding ring of men. Hoping to reduce the pressure, I told some of the hecklers that Nathan, in one of the toughest battles of the war he was now lambasting, had proven himself a bona fide hero; but this was like water off the back of a duck. “Maybe he’s shell-shocked out of his senses,” they said, then shrugged and turned back to scream at him. That evening, Peace Now demonstrators, grimly bound together in a compact phalanx, marched through the streets of Jerusalem, surrounded by jeering crowds, all the way to the prime minister’s office, where the government was still deliberating. Yonah Avrushmi, who saw himself as a protector of Sharon, hurled a grenade at them, wounding many and killing Emil Grynzweig.

It was the first political murder I had experienced in Israel, and I can think of only one since then. Faced with the looming mayhem, the government removed Sharon from his post. We swore that he’d never be back.

Eighteen years later, in July 2000, Prime Minister Ehud Barak set off for a second set of trilateral Camp David peace talks with the American president, Bill Clinton, and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat. Thousands of us converged in front of his residence to demonstrate our support. The first speaker, Tzali Reshef, had been prominent in Peace Now since its inception; now he was in his late forties. He reminded his audience of more than two decades of activism for peace—often in an atmosphere of severe public animosity, since the movement had demanded that the dream of retaining control of the West Bank be dropped. And now an elected prime minister with a mandate to withdraw from the territories was off to reach an agreement with Arafat. “This is the moment!” he thundered.

A few weeks later Barak was home, but there were no crowds to greet him at the airport. Israel had been dismantling her control over the Palestinians since the Oslo Accords in 1993. At Camp David, Barak had effectively offered an end to the occupation, with Israel to evacuate whatever territory she still held in Gaza and at least 90 percent of the West Bank, while dismantling many settlements; Israel would recognize an independent Palestinian state in all of the evacuated areas. In Jerusalem, Barak offered to divide the city, insisting only on Israel’s retaining some sort of connection, even symbolic, with the Old City and the Temple Mount. In return, he expected the Palestinians officially to declare that the conflict was over. Bill Clinton praised Barak for his far-reaching offers, while dejectedly noting that Arafat had simply turned them down without making any counteroffers.

Shlomo Ben-Ami, acting foreign minister, took off on a whirlwind tour of foreign capitals, to explain what had happened at Camp David. Wherever he went, he was congratulated on the positions Israel had taken while being encouraged not to give up. And indeed, the diplomatic activity between the sides was still going on. On September 24, Barak hosted Arafat at his home; after the meeting, negotiators from both sides flew to talks in Washington.

On September 27, an Israeli soldier, nineteen-year-old David Biri of Jerusalem, was killed by a bomb at Netzarim, an island of Israeli-controlled territory in the Gaza Strip. It was the first such attack since Barak had offered to dismantle and evacuate it, along with the other remaining settlements in Gaza. In other words, every single casualty there from August 2000 onward will be senseless, as the Palestinians are fighting for something they could have had without bloodshed. The second intifada had begun.

The next day, opposition leader Ariel Sharon and his entourage visited the Temple Mount. The visit had been cleared in advance with Palestinian authorities. Shlomo Ben-Ami, no friend of Sharon, had spoken personally about it to Jibril Rajoub, one of the top Palestinian security officials; Rajoub had told him that as long as Sharon stayed away from the mosques, there would be no problem. The visit itself was short and uneventful; Sharon told reporters how important the Temple Mount is to Jews, and left.

Friday, September 29: Muslim rioters on the Temple Mount dump rocks on Jews praying at the Western Wall below. A picture on my desk shows a four-year-old girl, crying with terror, being pulled away from the wall by her mother; other women are racing off; a policeman is screaming at them all to get away. Up on the mountain, five demonstrators were killed in the ensuing clash with police. Yossi Tabaja, an Israeli policeman on a joint patrol near the town of Kalkilya, was killed when one of his Palestinian colleagues simply walked over and shot him.

For the next two days I heard no news. It was Rosh Hashanah, one of the most solemn dates of the year, and we spent long hours in the synagogue. The climax of the day, I have always felt, is the segment written in the eleventh century by Amnon of Magenza, as he lay dying from torture inflicted for his refusal to convert to Christianity. Magenza was the Jewish name of the German town of Mainz, although I have yet to meet a single German who recognizes it. A few years later, the whole community was destroyed by Crusaders on their way to Jerusalem. The survivors fervently adopted Rabbi Amnon’s powerful passage about the awesomeness of the day each year on which God decides who will live and who will die. Fittingly enough, the possibility of living for another year is noted briefly, while the possibilities of death are multiple: “who by water, who by fire, who by the sword, by the beast, by hunger, by thirst. . . . Man is as a broken shard, as hay on the wind, as a wilted flower, as a passing shadow, as a fleeting dream.” A tradition that calls forth such poetry from the bloody rubble is surely worth living—and fighting—for. Some cultures would call forth only hatred.

Sunday night, with the two days of prayer and reflection behind me, I got on the Internet and visited The New York Times. The horrifying picture of a twelve-year-old Palestinian boy named Muhammad al-Durrah huddling in terror next to his father, moments before he was shot, struck me like a fist in my face. As a liberal humanist, a lover of peace, and a seeker of justice, and as the father of a twelve-year-old son, I recoiled from the image. My first response was an internal cry of pain; externally, a compressing of the lips and a grim condemnation of our inability to keep the children out of our wars. That picture is on my desk as I write, and I have spent many hours studying it, etching it on my mind and soul. It is an incredibly powerful image—so powerful, indeed, that it took me weeks to understand the truth of it: that it happened at Netzarim, a place that had already been surrendered. That Muhammad’s father had been screaming to his own compatriots for a brief pause in the firing; that a French cameraman—mysteriously alerted to the attack ahead of time—had been standing a few yards away but rather than join in the pleas of the anguished father had merely kept his camera trained on the picture of his career; that the Palestinian fighters themselves were so intent on redeeming by bloodshed what they had refused to accept by negotiation that it never crossed their minds to stop shooting; and that given the terrain and the range, it was highly unlikely that the Israeli soldiers had any idea a child was there. Hunkered in their trenches, being shot at from three sides just a few days after David Biri’s death at the same place, they could not be accused of having calmly and maliciously shot down a child; only a fool would say otherwise.

But that is precisely what my good friend Arthur turned out to be. Arthur is an English academic who takes his non-Jewish students each year to visit the Nazi death camps in Poland. In a heated exchange, he placed the entire blame for the violence on Sharon and, implicitly, on Israel’s insistence on occupying Palestinian territory; he further declared that Sharon was a war criminal and that in a normal country he would have been tried for his crimes. Going over the top, he likened Sharon to Slobodan Miloˇsevi´c, the Serbian leader who has the blood of hundreds of thousands on his conscience, the dynamo of an entire decade of calculated murder of civilians, concentration camps, and systematic ethnic cleansing. This was too much, and for the first time in decades I found myself defending Sharon by replying that these events were a bit too grave to be glibly assigned to him and that if one were looking for a leader with the blood of innocents on his hands, Arafat would easily qualify. In response, Arthur severed his relations with me—a decade of friendship, gone in the puff of an e-mail.

Also gone forever was my second, laboriously constructed, revised understanding of the Zionist project. In this version, so typical of my own post-1967 generation, powerful Israel had to reach out her hand to the aggrieved Palestinians and offer them generous terms of peace and reconciliation, and if she did so, the Palestinians would inevitably return the gesture in kind, because after all, everybody prefers peace with dignity to war with suffering. Nothing to come in the months and years ahead would allow me to get back to where I had been.

On October 12, Yosef Avrahami and Vadim Novesche, two reservists who mistakenly entered Ramallah, where Arafat has his headquarters, were lynched by a mob in the center of town. The purportedly wild and uncontrollable mob had the presence of mind to confiscate the film from all of the cameramen present, except for an Italian who smuggled out video images of the killers exultantly bathing their hands in Jewish blood. It was a deeply shocking illustration of the savage hatred of the enemy we had thought we were making peace with: say what you like about Israeli policies, we could not think of a single case where Jews washed their hands in the blood of their enemies. The army warned the Palestinians to clear the police building where it happened and rocketed it from the air. No one was hurt, but the pictures told their own story: here the impotent mob, there the arrogant helicopters; there the almighty occupiers firing from the safety of the air, below the despairing occupied people, venting their frustration with their bare hands.

The Palestinians seemed to feel that they were winning. Superficially, they were. That one image of twelve-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah was more powerful than seven years of Israel transferring real power to the Palestinians; Barak’s proposals at Camp David were as nothing when compared with the deaths of children confronting Israeli soldiers. In the first intifada, the working assumption had been that since it was an unarmed population facing the Israelis, the tremendous power of their army had been neutralized; should the Palestinians use firearms, however, the Israelis would be free to react with force and crush the uprising. This time, in the second intifada, the Palestinians were using automatic weapons from the first, the Israelis were responding with the tiniest fraction of the firepower at their disposal, and still the world reacted with abhorrence. In other words, the Palestinians had nothing to lose except lives and much to gain. They realistically assumed that no Israeli government would offer them dramatically more than Barak had, so they were trying the double track of violent pressure at home and massive pressure abroad, on the reasonable assumption that this would lead to even better terms: when you hold a winning hand, why stop playing?

But they had badly miscalculated. After all the speeches and declarations and resolutions, the Palestinians must make peace with Israel, not with the UN or the European Union. The opinion of the American president is reasonably important, but at the end of the day, the Israeli electorate is the only body that can agree or disagree with the terms the Palestinians seek. Now, however, the Israeli electorate was furious at the Palestinians—and nowhere near breaking.

The first group to tire in this cruel war of attrition was that of the large numbers of Palestinian men who daily went out of their way to seek Israeli military outposts beyond the perimeters of the enclaves ruled by the Palestinian Authority (PA), there to taunt the soldiers and to act as live shields for the armed men firing from their midst. After a month or two, however, they dropped out of the confrontation. From then on, it was armed men against Israelis—though preferably not Israelis of the lethal kind. The settlers in their civilian vehicles were a much easier target, and much of the international community regarded them as legitimate prey, since the Palestinians were purportedly resisting occupation and displacement.

No one gets worse press than the settlers. They are portrayed as the evil and violent edge of Israeli society, their greed for Palestinian land the engine of the entire conflict. My own relationship with them has long been ambivalent: I objected to their goals but liked many of them personally. Almost all the people I went to school with grew up to be settlers. Two weeks into the violence I had lunch with three or four of them, and they were complimenting themselves on their prescience: they had known the Palestinians were not going to make peace and had managed to provoke them into showing their hand. “Stop kidding yourselves,” I responded. “This has nothing to do with you. If the Palestinians had been willing to make peace with me and my kind, you wouldn’t have impeded us. The truth is that the peace efforts blew up over Jerusalem, over the right of return, perhaps over our very existence here—anything but the settlements, which Barak was willing to dismantle.”

By November, settlers were being shot down on the roads to their homes. Colleagues who live in Efrat or Ofra took to leaving work early in order to be home before nightfall; one of my staff didn’t come to work one day at all, going instead to the funeral of her neighbor, murdered in his car the evening before. Yet contrary to their image as Zionist fanatics no less militant than their Palestinian counterparts, they restrained themselves. Practically every household in the settlements owns a firearm or three, and many are armed with automatic weapons loaned on a permanent basis by their reserve units. There are forty-five thousand armed Palestinians, we were told. The number of armed settlers was at least as high, many with military training and experience far exceeding anything the Palestinians can offer. Yet surrounded by violence that threatens the lives of their wives and children, these supposed warmongering extremists refrained from using their firepower, even when faced with the most outrageous provocations.

Dr. Shmuel Gillis, forty-two years old and father of five, was a hematologist at Haddassah Hospital. His colleagues told of his outstanding professionalism and his contribution to the international research team he belonged to; his patients told of his warm bedside manner. After he was shot down as a settler, even his Palestinian patients mourned with the others, sharing their grief openly with the media. His funeral set out from Haddassah with thousands of participants; additional thousands lined the road south of Jerusalem on which he had been shot, standing in silence.

A few days later, Zachi Sasson was killed, again just south of Jerusalem. Also a settler, he had formerly been a congregant at my synagogue, so someone put up an announcement of the funeral details, including the promise of bulletproof buses. Yet ironically, the attacks on the settlers may have achieved the opposite of what their perpetrators intended. The murderous campaign had spread to Jerusalem and the Israeli towns of Hadera, Holon, and Netanya, blurring the line between the settlers and the general population. The settlers, by virtue of their restraint, had driven home the feeling that their predicament was shared by all of us and was part of a strategic Palestinian move against all Israelis—indeed, against the very existence of the Jewish state.

For decades I had been voting for candidates and parties who promised to leave no stone unturned in their efforts to achieve peace. The violence of the second intifada had totally undermined the agreements on which the peace process agreed to at Oslo had been predicated, but one might still hope that by offering them everything we could possibly afford to give, they might conclude that they had reached their utmost realistic goals and make peace. It is hard to think of a worse way to negotiate, but in order to save lives on both sides and to rectify the injustices we had done over the years, perhaps this was the last stone we must turn. But as the Palestinians began to murder Israeli civilians deep inside Israel while proclaiming that they were struggling against an unjust occupation that we had just tried to end, this position seemed increasingly irrational.

As Barak fell from power in December and new elections were set for February 2001, I was forced to admit that the rational choice would be to vote in a way that reflected what was happening around me; sticking to my liberal guns might be what my heart wanted, but it was not what my mind dictated.

There were to be no blank ballots for me. It is duty of the citizen to vote, I have always felt, and if you can’t make up your mind, then agonize over it until you can. But could my heart survive a vote for Sharon?

Zeituni is an uncommon name, and the family that bears it has a long history: they can prove that their forebears never left this land during the entire two thousand years when most Jews were elsewhere. In recent centuries, they resided in the Galilean village of Peki’in; today, the synagogue of Peki’in is their only relic. The populace is Arab, and the Zeitunis live elsewhere.

In January 2001 a young man named Etgar Zeituni, owner of a restaurant in Tel Aviv, went to the Palestinian town of Tulkarm on business with his cousin Motti Dayan and an Arab Israeli. Sitting in a restaurant, they were abducted by local thugs, given two minutes to pray, and shot. The Arab Israeli was sent home.

A young Jew whose family has been here for millennia, uprooted from the ancestral village that has become Arab, trying peacefully to do business with individual Palestinians in spite of the national tensions, and being murdered for his efforts. A true story to fly in the face of every platitude you have ever heard about the conflict in the Middle East.

The murder took place while high-ranking teams from both sides were convened at Taba, just over the Egyptian border. Barak froze the negotiations for thirty-six hours, and these—so the optimists claimed—were all that were lacking to clinch a deal.

Barak had not been backed by a majority of the Knesset when he went to Camp David; but neither had he been toppled, and in any case he could plausibly say that he was doing precisely what he had said he would do before being elected by a large majority a year earlier. Yet his efforts to make peace had resulted in war, and by January 2001, the polls were unanimous that he was going to be severely thrashed. Only a treaty could save him.

Bill Clinton’s proposals for bridging the gap addressed the two crucial issues: Israel would have to acquiesce in a clear division of Jerusalem, with no Israeli connection, not even symbolic, to the Old City irrespective of what was holy for the Jews; the Palestinians, for their part, would have to renounce their right of return. Whether Barak had a mandate to agree to such a proposal was unclear, but it was also irrelevant, as the Palestinians rejected it without making a counterproposal. The discussions at Taba were Barak’s last desperate attempt to reach an agreement by moving even closer toward the Palestinians than Clinton’s proposals: territories would be swapped so that the Palestinians would have the equivalent of 100 percent of the occupied territories; most significant, however, the Israelis were willing to discuss formulas that would recognize a legal Palestinian right of return, though perhaps not an unlimited practical right. All the Palestinians had to do was halt the violence, presenting the Israeli electorate with a harsh choice between Barak, poised on the cusp of a treaty, and Sharon. Instead, the murders went on.

The positions of the two sides were clearly set out at a press conference at Taba, on the final evening of the talks. Shlomo Ben-Ami, our foreign minister, spoke Hebrew; Abu Ala, the senior Palestinian negotiator, spoke Arabic and was translated simultaneously. Each spoke to his own constituency. Ben-Ami was full of sweetness: our mutual trust has been reestablished, he proclaimed. Vote for Barak next week, and peace will come shortly thereafter, he almost added. Abu Ala was less sanguine. Yes, progress had been made toward putting an end to Israeli aggression, he announced, but the main sticking point remains the right of return. The Israelis, he told his people, were not yet ready to accept this inalienable right; if they did not, he asserted, the Palestinians had assorted methods to force them. Vote for Sharon next week, Abu Ala had more or less told us, since peace is not going to happen, and he’s the candidate who knows it. Despite Sharon’s unsavory past and my aversion to him personally, the new reality required that I vote for him.

There were four reasons for this choice: two for voting against Barak and two for supporting Sharon.

First, the putative Israeli peacemakers had to be ousted—nay, overwhelmingly routed—in order to demonstrate to the Palestinians that the proper response to violence and perfidy cannot be further concessions. Concessions are a possible component only of a process of mutual compromise. Barak had offered concessions at Camp David, but the Palestinians demolished the underpinning of the entire Oslo process by returning to the violence they had irrevocably forsworn in 1993. The only acceptable response should have been to halt negotiations as long as the violence continued.

The concessions suggested by Israeli negotiators at Camp David were probably greater than the mandate given democratically to Barak in 1999; but had he brought peace, he would easily have swayed the electorate. The concessions made after the violence began went much further, and by throwing him out by the widest landslide imaginable, the electorate stated clearly that whatever he had offered in those last few months had been the desperate manipulations of a small group out of touch with the popular will.

These were two reasons to vote against Barak. One reason to vote for Sharon was precisely his image in the Arab world as a dangerous warmonger: since the Palestinians were obviously reading Barak as an appeaser who could be pushed to the limit and beyond, they must be shown that the Israeli public was in no mood for appeasement. Finally, in the event of any future negotiations, our representatives must be of the hard-boiled skeptical sort, since the trusting, optimistic, peace-seeking ones had proved disastrously naive.

All this, however, was merely political tactics. I had not yet resolved my existential turmoil. Whatever the Palestinians were doing could not erase my memory of our own wrongs, as I had learned of or experienced them since that afternoon in 1973 when we shot down that Libyan airplane; but nothing I had learned could really explain the situation we were in, and I concluded that once again my own Zionism had to be thoroughly reevaluated.

Meanwhile, things went from bad to much worse.

The Palestinians greeted the election of Sharon with more violence. In the month between his victory at the polls and the presentation of his new government, there were five lethal attacks on Israelis, with fourteen noncombatants dead, one of them eighty-five years old. This is not to count the botched attempts, such as the bomb in Mea Shearim that merely wounded four pedestrians. Arafat had freed all the Hamas and Islamic Jihad terrorists who had been in Palestinian prisons since the previous wave of violence in 1996, and it took them only a few weeks to start sending new suicide murderers against Israeli targets.

Much of the international press, meanwhile, was declaring that Sharon’s electoral victory meant war. On March 7, 2001, CNN announced with a straight face: “Sharon Can Choose Between Peace and Violence, Arabs Say.” Given that Barak had chosen peace and received violence, this assertion was rather startling. The Economist (London) had warned us before the election that if we chose Sharon, we would be saying no to peace; the following week, they greeted our democratic decision by adorning their front page with a picture of Sharon against a black background and the headline sharon’s israel, the world’s worry. Once in office, Sharon laid down new rules for the renewal of negotiations: First, there had to be an end to violence. The Economist characterized this reasonable demand, consistent with the Oslo Accords, as “unadorned extortion.” The Guardian greeted the election with a caricature of Sharon leaving bloody handprints on the Western Wall and ran an article by Seamus Milne calling for sanctions against Israel for daring to elect a war criminal worse than Chile’s Augusto Pinochet.

Less than three weeks into Sharon’s term, the Danish foreign minister explained that the Israeli occupation was the reason for the conflict. The context of his statement were discussions at the UN about sending an international force to protect the Palestinians. At the Arab summit at Amman in March 2001, the UN secretary-general, Kofi Annan, harshly criticized Israel for her occupation of Arab land and said that Israel’s “collective punishment” had fed Palestinian anger and despair. Pierre Sane, Amnesty International’s secretary-general, made a series of demands, including armed international observers in the West Bank and Gaza and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Yasser Arafat must have felt like a mainstream leader when stating in his speech at the Arab summit that “Israel’s occupation is the greatest terrorism possible, while the Palestinians reject terrorism and seek peace.”

Those were the speeches. The actions on the ground over the same two days seemed to be taking place on a different planet. In Hebron, a Palestinian sniper shot and killed ten-month-old Shalhevet Pass in her stroller on a playground. A bomb was defused successfully in the center of Petach Tikva. Another bomb went off but killed no one in southern Jerusalem. In the early afternoon—precisely as Arafat was giving that speech, which was broadcast live—a suicide bomber detonated himself on a number six bus headed into our neighborhood. Both of my sons and I take that bus every day.

The first few weeks of Sharon’s government were characterized by a serious attempt to lighten restrictions on the Palestinian populace, including the careful lifting of blockades around Palestinian cities. In the old, pre-Oslo days, such blockades had been unnecessary, since Israeli security forces ruled the towns directly and were free to do their utmost to get at potential terror cells. This had caused countless ugly scenes and made people like myself eager to find a way to get out of there, but in retrospect it had been far cheaper in human lives on both sides and had also been easier for the Palestinians to live with: as long as there wasn’t a curfew—and most of the time there wasn’t—they were free to lead their normal lives, and large numbers of them daily entered Israel to work. The second

intifada saw the Palestinians armed and organized as they hadn’t been in the first, and the Israelis were forced to work with blunter tools.

The lightened restrictions were accompanied by a sharp rise in Palestinian attacks on civilian targets inside Israel. There were six suicide attacks and six car bombs in two months. In the past, one might have said that terror was the price for Israeli control over the Palestinians. But what did the murder of civilians in Netanya, Kfar Saba, and Hadera have to do with negotiations in which Israel had already ceded just about everything there was to cede and had clearly stated that she did not want control over the Palestinians? Was there anything we were withholding that could by any stretch of imagination justify this?

Sharon’s government was caught between the impossibility of appeasing the Palestinians, which in any case it had been elected not to do, surrendering to the strident demands of the international community, and fulfilling the fundamental task of government: protecting the lives of its citizens. After the murder of five civilians doing their shopping on a Friday morning in Netanya, F-16s were sent to bomb a police station in nearby Nablus. The shrieks of international protest were deafening. Then, on June 1, 2001, a suicide bomber finally managed to kill lots of Israelis, almost all of them children, at the Dolphinarium discotheque in the middle of Tel Aviv.

In an unimaginable act of self-restraint, Sharon did nothing. Joschka Fischer, the German foreign minister who was coincidentally down the block when the bombing occurred, beseeched the Israelis not to retaliate and shouted at Arafat that the violence had to cease. The Israelis waited, proving to those who already knew that there was no “cycle of violence” in the Arab-Palestinian conflict, merely one-sided aggression. The lull lasted four days, and on June 5, five-month-old Yehuda Shoham had his head smashed by a rock thrown at his parents’ car. That week, Le Monde put a caricature on its front page by Plantu, its prize-winning cartoonist. Captioned “Kamikazes,” it showed two equally repulsive individuals, one with explosives strapped around his hips and the second with the houses of a settlement strapped around his. By the end of June, eight more Israelis had been killed, four of them civilians, as well as a Greek Orthodox priest who was driving a car with Israeli plates.

By training I am a historian, but by occupation I’m the director of an archive. In mid-August, a friend showed me the results of some family research that had recently been carried out in a Polish archive. Someone had dug up the registration forms that the Jews in one town were forced to fill out when the Germans arrived; most of the forms contain snapshots. It was the first time my friend had ever seen a picture of his father as a young man, before the Shoah. It was also the first time he had seen pictures of his aunts, who did not survive. For him, the astonishing thing was the incredible similarity of his own daughter to one of the aunts. It was almost as if she had been given a second chance at life. For his daughter, the discovery served as a trigger to develop a serious sense of her own participation in the flow of Jewish history. Fifteen-year-old Malki Roth was murdered at the Sbarro pizzeria in the center of Jerusalem.

The awesome Israeli response to the second mass murder of civilians in ten weeks? To shut down the unofficial Palestinian “foreign office” in Jerusalem, at the Orient House. The number of dead Palestinian civilians: none. The number of wounded Palestinians: none. The number of dead or wounded Palestinian gunmen: none. The irrevocability of the action: until decided otherwise. Yet inexplicably, the BBC led the pack in screaming about Israeli revenge. Yossi Klein Halevy found a fine metaphor for being an Israeli in 2001: like being trapped in a soundproof room with a psychopathic killer, while outsiders peered in and clucked about the lunatics.

On September 11, 2001, terrorism on an unimaginable scale reached America. Clyde Haberman of The New York Times, recently back from Jerusalem, asked his readers, “Do You Get It Now?” Our enemies, and those who pretend to be our critical friends, gloated that this was retribution for the one-sided American support for Israel. The French ambassador to Israel caused an uproar when he stated the European line that Osama bin Laden was evil incarnate, but the Palestinians had a case. Yet in America, a growing number of people now felt that terrorism cannot “have a case.” No one who chooses to pursue political ends by such immoral means deserves a civilized hearing, no matter what the grievance.

The next month, at a conference on Nazism in Hamburg, a participant told me that where people live in fear, they will also hate. I responded sharply: “My teenage children are growing up with fear, and rightly so, but they’re not allowed to hate.”

On December 1, 2001, two suicide murderers and a car bomb struck in the center of Jerusalem. Eleven teenagers were killed. Meir, my seventeen-year-old son, was standing around the corner of a building, so that he and his friends emerged physically unscathed. But they saw things that one should live an entire life without seeing.

Before it hit the radio, he called to tell us he was all right. Even as he was on the phone, we heard them taking stock: “Efi’s over there. He’s all right! Did you see Itai? Where’s Itai?” So what he had to tell us was that he was all right, but also, “I can’t find lots of my friends, and there are dead bodies lying around.” There was a tone of panic in his voice. When we finally reached him, he kept telling us, over and over, how someone with a torn leg was leaning on him until a medic appeared, thanked him, and then shouted, “Now get the hell out of here!”

The next day he tried to work it over. “We should send them all to Afghanistan. All these Palestinians. They can have as many square miles as they want, they won’t be crowded there.”

“You’ll uproot millions of them?” I asked.

A few minutes later, he had dropped that solution and was searching for another. “Let’s go in there and arrest all the able-bodied men from eighteen to forty and put them in a big ravine. Then we’ll bring in all of the judges we have, and we’ll stand each of them before a judge. There will be three verdicts: to be shot, to spend the rest of your life in jail, or to go home. Some we’ll shoot, most will go to jail, and a very few we’ll send home.”

“Hundreds of thousands of people? Doesn’t sound like justice to me.”

“Well, what can we do? What kind of a people is this that proudly sends its men to blow up children?” I had no answer to that one. “I want them gone! All of them!”

“Meir, you know I’m not willing to hear such talk, even tonight.”

He wandered off to his room—until he came back with another harebrained scheme, knowing it was unacceptable but having to say it, having to hear it rejected.

He had encountered evil, in its pure and unadulterated form. Most of his contemporaries in the West, along with their parents, their politicians, their journalists and academics, never have and never will; going by the things they say and write, they will never understand what Meir did at seventeen.

Sometime in March 2002, as the suicide murderers were hitting us daily and their compatriots were deliriously celebrating their heroes, I sent an e-mail to some twenty or thirty non-Israelis, Jews and non-Jews, Americans and Europeans: “Can any of you give me one compelling argument why Israel should not militarily dismantle the Palestinian Authority, throw out Yasser Arafat, collect all the arms she can, and kill all the Palestinian arms bearers who won’t hand over their weapons?” I was surprised how many replied with a weary “No,” but some reiterated the accepted wisdom about the impossibility of achieving anything by force of arms, though it flies in the face of the entire history of mankind. It also overlooked, willfully or foolishly, the truth about the Palestinian violence: that they had every intention of achieving quite a bit by force of arms and that by early 2002 their hopes were rising daily. Israel surely couldn’t go on much longer under the strain of daily, and soon hourly, mass murders of civilians by seemingly unstoppable suicide bombers. Soon she must either start to collapse or, at the very least, plead for a cessation of hostilities in return for vastly worse terms than she had offered at Taba, terms that would lead to her future demise. Either that or she would retaliate with such brutality that the international community would be forced to step in and save the Palestinians, who would be free to continue their campaign from behind the apron of external forces unfriendly to Israel. The conventional view was that the suicide bombers were motivated by “despair,” but as columnist Charles Krauthammer noted, the real motivating force of these attacks was not despair but hope. Hope that Israel could be broken and, ultimately, hope that she could be destroyed. It was crucial that they be knocked out of their hallucinations.

What remained was the response of one of my more naive friends, a Jew living in Europe, who objected to my suggestion because “I wouldn’t want to live in a world where people do things like that.” Meaning, I think, that it would be immoral, though for the life of me I couldn’t see how.

A week later, a suicide murderer struck at the Park Hotel in Netanya, killing twenty-nine Israelis as they sat down to the Passover seder table—the most family-oriented moment in the year. So Israel finally did what she had to do. By going after the master terrorists and their thugs in their own lairs, she changed the rules of engagement. The symbol of this was the battle of Jenin—actually a battle for a small section in a small town, about the size of a football field, where the worst of the murderers were holed up in a residential area, surrounded by tons of carefully laid explosives and booby traps. Rather than vaporize them safely from the air, as they were well equipped to do, the Israelis fought inch by inch. Battle in such conditions is more than anything else a test of mettle, tenacity, and, ultimately, the resolve to win, as the Palestinians knew what was coming and had time to prepare. This explained the near parity in casualties—fifty-two Palestinians to thirty-three Israelis. The Israeli victory in this brutal contest of wills hammered home the understanding that things would not continue as they had. The tide had turned.

Which may have been precisely the reason for the orgy of hatred directed at Israel by most of the world that week. Shrieks of loathing told of an Israeli massacre of hundreds of civilians (the Palestinians told of thousands). Television panelists and newspaper pundits expounded with smirks of satisfaction that “the Butcher of Beirut” was finally showing his true colors. So-called peace activists flocked to the assistance of the Palestinians; one sent me an e-mail about how she was saving Palestinian lives from Israeli aggression, as once a handful of righteous Europeans had saved Jews from the Nazis. Leaders of nations got on the phone to Sharon to protest the siege of Arafat, never once inquiring after the dozens of wounded from the real massacre of civilians that had just taken place in Netanya. Tens of thousands of demonstrators poured onto the streets of European capitals to protest Israel’s supposed war crimes, and a prominent German politician castigated our Vernichtungskrieg, a Nazi word that means war of annihilation. The United Nations set up a commission of inquiry into the “crimes” committed at Jenin, headed by a Swiss official by the name of Saramuga who had in the past compared the Magen David to the swastika.

My friend Esther Golan is a Holocaust survivor in her late seventies. On the afternoon of Yom HaShoah, the day of remembrance of the Holocaust, we were to appear together at a public event where she would donate to Yad Vashem a sheaf of letters written by her mother sixty years ago. The mother, despairing of ever again seeing her children, had clung to the hope that somehow, someday, they could be “reunited in our own land,” right up until she was sent to Auschwitz. Esther did not appear that afternoon. Her grandson, Eyal Joel, was killed that morning in Jenin. When I visited her a few days later, she asked me if she was losing her grip on reality or was it the world? I assured her it was the world. By this time, I had been grappling with the issues for more than a year, and I felt that I knew how to prove this.

The Jews were humanity’s first monotheists, and monotheism, in its complex way, is universal. It does not necessarily expect everyone to believe in it, but it does allow anyone to do so. It states that there is one God who created us all, and it welcomes anyone, irrespective of race, gender, status, or wealth. It also asserts that there is a universal morality. There are countless caveats, but this is the fundamental position. Living in a Jewish context means accepting that cognition and morality both are fundamentally universal.

The premise of this book is that there is, at least sometimes, an objective truth that can be known; there are modes of investigation and deliberation that are open to all, which can be used to determine it. Morality too is universal; while not everyone will agree about what is moral in every circumstance, anyone can, potentially, identify it. Truth and morality are not owned by any group, although it is conceivable that some individuals or groups will be moral more often than others. But this will be something that anyone can test empirically, if one is honest about it.

Some readers will disagree that morality is universal, but if that were so, there would be no way to make any judgments at all. Given the intensity and pervasiveness of opinions on Israel’s behavior, however, most people obviously do feel that there are moral criteria by which it can be measured and judged.

The case against Israel is varied, detailed, and harsh. Most Westerners subscribe only to some of the main accusations; some of the allegations are mutually incompatible, but inconsistency has never stopped people from voicing opinions.

Zionism is rejected by definition, regardless of its policies or actions. It is cast as a European colonial project, which is about as devastating a critique as possible in this age of postcolonial guilt. Israel is actually the worst of all colonial projects, because it is the only one still around, after the others saw their errors and disbanded. Arabs compound this culpability by claiming that there is no evidence for a Jewish past in Palestine; Westerners cannot agree to this because it undermines Christianity and their own history, but they agree with the Arabs that even if there was a Jewish past, it is too ancient to be meaningful today. Finally, people who regard themselves as proponents of a universal humanism dislike Zionism for concentrating on the well-being of Jews alone: such concentration on a single ethnic group can only be an instance of racism.

Having denied the Jews the right to national expression in their land, the detractors bolster their position with claims about the practice of Zionism. The Palestinians, they say, were peacefully living their national life until they were invaded by Jews, who drove them off and stole their land. The Zionists always intended to destroy the Palestinians and won’t desist until this has been accomplished. Zionism is thus a genocidal movement with a long-standing penchant for terror against defenseless Palestinian civilians. As soon as British forces left Palestine in 1948, this view asserts, the Zionists did their best to evict the Palestinians from their homeland, and afterward they continued the persecution so as to stave off any possibility of peace before the task had been completed. In 1967, it is said, Israel provoked another war in which she conquered the parts of Palestine she did not yet control and evicted additional masses of Palestinians. When this still didn’t break the backs of the Palestinian people, the Israelis launched a program of settlement on expropriated land, cleverly planned to strangle the Palestinians. Even when Israel ostensibly negotiates with the Palestinians, she never does so in good faith; her real goals are to subjugate the Palestinians, directly or indirectly.

This version of history is so breathtakingly hostile to the Jews that most Westerners wouldn’t profess it in such a condensed form, but every one of its tenets can be found in the pages of many European newspapers. Its power lies in the kernels of truth it contains and is abetted by the ignorance of the readers—and perhaps of the writers themselves—who accept these distortions of fact since they fit traditional preconceptions about the Jews.

Given the inhumane policies of the Israelis, you begin to see why the conflict is so protracted. The Palestinians are infuriated by the injustice of the Zionist invasion, the brutality of Israeli occupation, and the violence of the settlers perched strategically on every hilltop. Their resistance is only natural, but since the Israelis insist on answering them with redoubled force, a vicious cycle has been created that can only get worse. The conflict has become an intractable blood feud that feeds on itself, and the protagonists on both sides have lost their senses. Morality no longer matters, since one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, but it makes all the difference, since the only way to end the conflict is for Israel to redress the injustices she has done. Since Israel is the powerful aggressor, she can afford to be magnanimous toward the Palestinians, who are weak and do not threaten her. Yet Israel rejects all this good sense, because her goal remains the destruction of the Palestinians and the annexation of their land in fulfillment of Zionist prophecies.

I have repeatedly asked critics of Israel to explain how they reconcile this view with the electoral victories of Rabin or Barak or the offers Barak made in 2000. Those who are willing to respond tell me that the whole thing was a hoax, Israeli propaganda; all Barak really wanted was to control the Palestinians indirectly instead of directly. It is astonishing how deep-seated the fear of covert Jewish power really is.

It is this primordial fear of the Jews, inculcated during centuries of animosity, that inflates the global importance of this conflict to irrational proportions. From the volume of vituperation hurled at her, one would think that tiny Israel threatens world peace and stability (as the French ambassador to the United Kingdom put it: “Why should we all be in danger because of shitty little Israel?”). People who hate the United States often hate Israel for being an American outpost. In recent years, however, a more potent strain of this theory has been raising its all-too-familiar head, as stated clearly in the letter of Saddam Hussein to the United Nations of September 19, 2002: “In targeting Iraq, the United States Administration is acting on behalf of Zionism, which has been killing the heroic people of Palestine, destroying their property, murdering their children, and seeking to impose their domination on the whole world. . . . You may notice how the policy of the Zionist Entity, which has usurped Palestine and other Arab territories since 1948, and afterward, has become now as one with the policies and capabilities of the United States.”

There can no more be a debate with such a viewpoint than there could have been in the early 1940s, when Nazi propaganda referred to the president of the United States as Franklin Rosenfeld. You might expect Western public opinion to be more sensitive to the dangers of such viewpoints, but you would be sadly mistaken. Saddam’s allegations, which are standard fare in Arab propaganda, failed to cause any consternation in the ranks of Israel’s detractors, no second thoughts about their partners in bile. As if the history of Jew-hatred never happened, they continue to assure us that the moment we redress all the Palestinian grievances, peace and serenity will reign. Or perhaps it’s the other way around: they frequently reprimand the Israelis for not learning the proper lessons from their own history. The Jews, of all people, should know better, goes the refrain. Having themselves suffered so grievously, they should be the last ones to inflict suffering on anyone else.

The maliciousness of this statement is complex. It insinuates that the Israelis are somehow treating the Palestinians as the Nazis treated them; it further intimates that the Palestinians are as innocent of evil designs as were the Jews of Europe; and while quite overlooking the fact that the Jews never murdered their tormentors, it excuses Palestinian crimes as the result of persecution. All of which leads to the conclusion that since the Jews so obstinately refuse to behave, Zionism has failed demonstrably and must be undone.

Take Oxford professor Tom Paulin, who in February 2001 published a poem about the “Zionist SS” who shoot down defenseless Palestinian children. When Paulin makes such comparisons, he is calling for the violent destruction of the Jewish state. What’s more, his vitriol is dangerously approaching mainstream discourse, as illustrated by the spat between some local politicians in Wales in January 2003.

A minor Labour politician, Ray Davies, called upon two midlevel Welsh politicians not to travel to Israel, which he characterized as an “apartheid state.” “Hitler’s Nazi regime occupied Europe for four years only. Palestine and the West Bank have been occupied for 40 years. . . . I do draw that comparison because [this is] one group of people who should understand what oppression is and what it is like living under occupation.” Davies himself had participated in a fact-finding trip to the occupied territories but proudly explained why he had “utterly resisted” the idea of going to Israel proper: “When they go out there they will be treated like lords and taken to the Holocaust museum to try to engineer as much sympathy as they can and shown the bright side and the pleasant side and the sort of life the Israelis are enjoying. . . . Anybody who goes to Israel will be taken to the Holocaust museum and shown what has happened to the Israelis. . . . But that does not give the Israeli government any right to do what they are doing to the poor beleaguered Palestinians for over 40 years. Life in Palestine and the occupied territories at the moment is nothing short of disgraceful.” He was joined in his plea by Welsh children’s poet laureate Menna Elfyn.

The refusal even to listen to the Israeli side indicates the irrational depth of the animosity and the impossibility of responding to it through dialogue—which has of course been a hallmark of antisemitism for centuries. As long as Israel can protect herself, the fact that she is despised by irrational people need not be a source of despair; if enlightened rationality is important, it should be a source of pride. The danger is that eventually rational people will begin to doubt the truth of what they know.

This book addresses itself to anyone open to a moral evaluation of the facts. Since the story of Zionism is intertwined with the story of its wars, an attempt to evaluate Zionism must be anchored in assumptions about the morality of war.

There are four main schools of thought on justifying war.

First, there are religious justifications, whereby wars are viewed as the enactment of God’s will. The Islamic conquests of the seventh to ninth centuries, or the Crusades that responded to them from 1095 onward, are prime examples. The modern atheists of this school replace God with the inevitability of History, as in Nazism and some stages of communism. These justifications are usually not universal, as the unbelievers or the osers of History are shut out—the Jews and other subhumans in Nazism; the bourgeois and kulaks in communism; and eventually the alleged intellectuals in Communist Cambodia. By definition, these wars will not be justifiable by universal standards of morality.

Others view warfare as an inevitable part of realpolitik—an extension of politics by other means—and therefore not a subject of moral considerations. Since they feel unbound by such considerations, the practitioners of this form of warfare often wage immoral wars. Most of Europe’s wars from the eighteenth century on were of this sort, climaxing in World War I, which started as just another war for the balance of power but got horribly out of hand because of the unnoticed advance of military technology in the decades preceding it. Africa’s unnoticed wars these days are also of this type: they are about power or greed.

Pacifists condemn all war, for any reason. This is an appealing school of thought, and if it could somehow be simultaneously inculcated in all of humanity, the world would be a much better place. In the meantime, pacifists allow themselves to stand aloof from unjust wars, effectively supporting the aggressors. Where they themselves are targets of aggression, they must either surrender whatever is being demanded of them, including possibly their lives and the lives of fellow citizens whom they are not willing to defend, or rely on someone else to do their fighting. The defeatism of the French in 1940, for example, was influenced by pacifism, with the result that the Nazi war machine routed them with an ease that belied their actual military potential and then deported seventy thousand Jews to the camps before the Allies fought the French war for them and stopped the murder. The Western European refrain of appeasers of the Soviet Union, “Better Red Than Dead,” was fortunately never tried, since others were willing to face the Reds and force them to back down. Refusing to use one’s power to stop murderers caused the deaths of tens of thousands in Bosnia in the 1990s and of hundreds of thousands in Rwanda. In such a world, pacifism is not morally defensible.1

Finally, there is the moral war school of thought, which recognizes that wars are a part of the human condition but seeks to regulate their conduct according to moral considerations. (I have drawn heavily, though not exclusively, on Michael Walzer’s account of this tradition in Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations, though I cannot say whether Walzer would be pleased at my adaptation of his thoughts.) This is the camp with which I and most other Israelis identify. As a school of thought, the moral war tradition is rooted in Christian theology, but its ultimate roots are in Jewish monotheism. The concept of war as a human activity that must be regulated by moral constrictions first appears in Deuteronomy, in chapter 20, for example, which regulates how the army should prepare for battle, how to lay siege and negotiate lifting it, and the relation to prisoners of war.

A crucial distinction in the discussion of morality and war is that between jus ad bellum, or justice in going to war, and jus in bello, or justice in waging war. The first asks whether one is ever justified in going to war in the first place and answers that nations may protect themselves against aggression and thereby ensure their right to define for themselves the kind of communal life they wish to live—the American Revolution being an obvious example. Intervention in the wars of others can also be justified, when the intervention is meant to put an end to aggression—the Kosovo campaign in 1999 being perhaps the clearest example, or expelling Iraq from Kuwait in 1991. Another point, not made by Walzer, is the price of ending the war, be it by surrender, negotiated settlement, or victory. The price each side will pay for peace can indicate what the original goals of being at war were and the degree of their morality. The American behavior after winning World War II speaks volumes about the morality of their fighting it in the first place; the fate of Czechoslovakia after Munich, in 1938–1939, proves how moral (though futile) a war against Germany would have been.

Jus in bello is the attempt to wage war according to a code, lest one’s actions nullify whatever justification there may have been for the original decision to fight. This is a separate issue from jus ad bellum and reaches down to the individual behavior of soldiers in the field, irrespective of whether the war they are engaged in is just. A just war can be waged unjustly, and an unjust war could conceivably be justly waged. The decisive issue is that war is to be waged by soldiers against other soldiers. Civilians and captured soldiers are not legitimate targets.

What I found in my review of Israel’s wars was that Zionism has mostly tried to be moral. Sometimes it made mistakes, from which it generally (but not always) learned. While being continuously at war, it was surprisingly, though not fully, successful at all sorts of other projects, such as the building of a reasonably healthy society out of widely diverse communities. Precisely because its overall record is basically positive, its citizens are deeply committed to its success, even in the face of violent rejection from its neighbors and widespread international condemnation. Much of this stems from ancient Jewish traditions that remain powerfully influential in modern Israel. As a country, it is not religious, but it is very Jewish, especially in the choices it makes.

For at the heart of all morality is choice. The biblical story of Creation underlines that choosing between good and evil is the essence of being human. (Marxist historical imperatives diminish our humanity by reducing our responsibility to choose morally.) The original Zionist choice was that the goal of Jewish national existence was worthy of considerable effort; subsequent choices have been concerned mainly with the permissible means for preserving it.

In April 2002, the government of Saudi Arabia tried to convince the rest of the Arab world to adopt an initiative to recognize Israel and make peace with her, under certain circumstances. The proposal was accompanied by considerable fanfare and an Arab Conference in Beirut. Whether the Saudis were sincere is hard to say, but even if they were, the fanfare obscured the underlying fact that after waging one war a decade since the 1940s, most of the Arab world has still not made the choice to accept Israel’s right to exist. The means chosen to affirm this lack of recognition were demonstrated some four hours after the discussion in Beirut, when twenty-nine Jews were murdered in Netanya at the seder table. The howls of protest in the West as Israel then decided to use force to protect her citizens were also a moral decision, as recognized by Arabs and Jews alike.

So if our enemies dispute our right to exist, let’s at least make certain that we can defend our actions to ourselves. This will add fiber to our resilience, fortitude to our determination, and encouragement to those allies still left with us. Ensuring that our wars are just will also ensure that those of our enemies are not, and this knowledge will strengthen our hand until the day they tire of spilling blood for what should not be achieved anyway.

Why I Voted for Sharon

The war against the Jews goes on. Jewish children are shot in their beds, and the shooters are celebrated as heroes. Jewish teenagers are blown up, and the mothers of their murderers exult. Elderly Jews are burned to death, and the killers gloat on their Web sites. And across the Arab world from Pakistan to Morocco, hundreds of millions have nothing better to do than to chant for the death of the Jews. If there was one thing to be learned from the twentieth century, it is that when people consistently say that they want the Jews dead, they may actually mean it. And when the rest of the world looks away or pretends not to hear, the killers take silence for acquiescence, acquiescence for concurrence, and concurrence for support.

Yet in our generation the Jews are quite capable of defending themselves, and that confuses the issue. The irrationality of wishing the Jews gone can hide—just barely—behind political considerations: the Jews must change before one can live with them. The immorality of passive support for the killers can hide—almost plausibly—behind censure of the way the Jews wield power: the Jews have brought their enemies’ ire upon themselves. Worst of all, the resolve of the Jews never to succumb can be whittled away by their own doubts about the wisdom of surviving by the sword and by their hopes of buying acceptance with political gambles: if only we were more benign and accommodating, our enemies would accept us.

The Jews cannot decide for the Arabs to accept Israel’s right to exist. They cannot decide for Israel’s Western detractors to accept the morality of the choices she makes. But Israel can and must do her utmost to ensure that her choices are moral and wise; when they’re not, they must be corrected. Jews care deeply about morality and always have; this has been a source of their strength in the face of enduring adversity. Since the adversity continues unabated, the strength that comes from being moral is as essential as ever.

My initial understanding of Zionism, while childish, was shared by most adults I knew. It had a good side, the Israelis, and a bad side, the Arabs, and they were so bad that their motives seemed almost inexplicable. The Arabs kept trying to destroy Israel, but Israel, partly by virtue of her moral methods of waging war, repeatedly rebuffed the heinous Arab attacks. The events of spring 1967—bombastic Arab speeches about destroying Israel, total international ineptitude in stopping them, if not even acquiescence, and then the seemingly miraculous Israeli deliverance and victory—these were the formative events of my childhood.

My arrogant complacency took its first blow on the gray afternoon of February 21, 1973, when our fighter pilots shot down a civilian Libyan airliner that had strayed into Israeli airspace over the Sinai. I was appalled by the deaths of everyone aboard and horrified by the total lack of remorse exhibited by the head of the army and the two civilians above him, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister Golda Meir. The plane had no reason to be there, they said. It had flown over a military installation. It could have been spying. There was no way to know—so they had ordered it shot down.

I was a teenager at the time, and in the first political act of my life I faced my peers with the demand that they agree that while Zionism was still fine, these particular Zionists must go. Almost no one agreed.

From 1975 I spent three years in the armored corps. The army I was in was still reeling from the ferocity of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, in which people I knew had been killed; we spent most of our time in the Sinai desert, training to stop and rout another Egyptian attack, should it come. To listen to Israel’s critics today, we were already a decade into the brutal occupation of the Palestinians, but neither I nor anyone I knew had any military encounters with occupied Palestinians. We served on the borders and faced Arab armies or Palestinian forces in Lebanon; the Palestinians under our occupation went to work in Israel, and while undoubtedly disliking us intensely, they did very little that called for brutal oppression. On vacations we would roam freely wherever we wished, at times taking Palestinian buses between Palestinian towns. One image stands out: eight or nine of us standing in a Palestinian town and Avi Greenwald cracking jokes in Yiddish, to the tremendous amusement of the young Palestinians grouped around us. Avi was killed a few years later, fighting the Syrians; I have no doubt that some of those young Palestinians were later killed fighting us. That simple scene is hard to conceive of today.