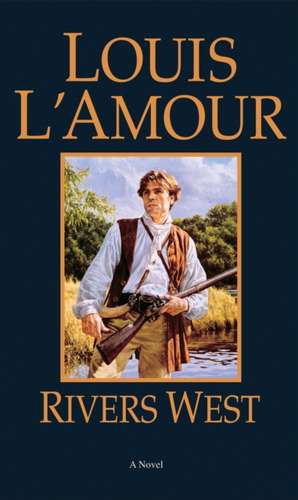

Rivers West: Discovering the Path to Self Transformation: Talon and Chantry

Autor Louis L'Amouren Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 oct 1989

Preț: 47.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 71

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.03€ • 9.46$ • 7.47£

9.03€ • 9.46$ • 7.47£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553254365

ISBN-10: 0553254367

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 108 x 177 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Bantam

Seria Talon and Chantry

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0553254367

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 108 x 177 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Ediția:Revised

Editura: Bantam

Seria Talon and Chantry

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Louis L’Amour is undoubtedly the bestselling frontier novelist of all time. He is the only American-born author in history to receive both the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal in honor of his life's work. He has published ninety novels; twenty-seven short-story collections; two works of nonfiction; a memoir, Education of a Wandering Man; and a volume of poetry, Smoke from This Altar. There are more than 300 million copies of his books in print worldwide.

Extras

A ghost trail, a dark trail, a trail endlessly winding. A dark cavern under enormous trees, down which blew a cold wind that skimmed the pools with ice. A corduroy road made from logs laid side by side, logs slippery with rotting vegetation from the swamp.

Here and there a log had sunk deep, leaving a cleft into which a suddenly plunged foot could mean a broken leg, and on either side of the swamp ... well, some said it was bottomless. Horses had sunk there, never to be seen again-and men, also.

My father's house lay several days behind me, back of a shoulder on the Quebec shore above the Gulf of St. Lawrence. For days I had been walking southward. An owl glided past with great, slow wings, and out in the swamp some unseen creature moved, seemed to pause, listen.

Was that a step behind me?

Astride a gap between logs, I paused, half turned to look.

Nothing. I must have been mistaken. Yet, I had heard something.

My shoulders ached from the burden of my tools. Straining my eyes in hte darkness, I looked for a place to stop, any place which to rest, if ever so briefly. And then I saw a wide stump from which a tree had been sawed, a full six feet in diameter. The tree cut from it lay in the swamp close by, half sunk.

With my left hand I swung my tools to the stump, keeping the rifle in my right, ready for use. This was a wild place. There were few travelers, and fewer still were honest men. Young I might be, but not trusting.

For the first time I was leaving my home, going south from Canada into the United States. Westward, it was said, they were building, and we are builders, we Talons.

There was a time when at least one of the family had been a pirate. He had been a privateer in the waters of the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and the Red Sea, but mostly off the Coromandel and Malabar coasts of India. He'd done well, too, or so it was said. I'd seen none of the treasure he was said to have brought away.

What was that? I half rose from my seat on the stump, then settled back, holding my rifle in both hands.

It was cold, growing colder.

Behind me, on the Gaspé, I had left my father's cottage and the good will of at least some of my neighbors. My father was gone. My mother had died when I was yet a young boy, and I had no sweetheart.

Of course, there had been a girl. We had roamed the fields together as children, danced together, even talked of marriage. That was before a man far wealthier than I had come to see her father. To be wealthier than I was not difficult, for I had only the cottage inherited from my father, a few acres adjoining, a small fishing boat, and my trade. And she was ambitious.

The other man was a merchant with many acres, a three-masted schooner trading along the coast, and a store. He was a landed, a moneyed man, and, as I have said, she was ambitious.

She had come to our meeting place one last time. At once she was different. There was no fooling about on this day, for she was very serious. "Jean!" She pronounced it zhan, as was correct, but with an inflection that was her own. "My father wants me to marry Henry Barboure."

It took a moment for me to understand. Henry Barboure was nearly forty, twice as old as I, and a respected, successful man, although I'd heard it said that he was close-fisted and a hard man to deal with.

"You are not going to?" I protested.

"I must, unless ... unless ...."

"Unless what?"

"Jean, do you know where the treasure is? I mean all that gold the old man left? He was your great-grandfather, wasn't he? The pirate?"

"It was further back than that, " I said. "And anyway, he left no gold. None that I know of."

She came closer to me. "I know it is a family secret. I know it's always been a secret, a mystery, but Jean ..... if we had all that gold ... well, Father would never think of asking me to marry Henry. He always told me you'd know where it was, and you could get some of it, whenever you liked."

So that was it. The gold. Of course, I knew the stories. They had been a legend in the Gaspé since the first old man's time. He had been one of the first to settle on what was then a lonely, almost uninhabited coast. He had built a strong stone castle-burned by the British during one of their raids on the coast many years after, and attacked many times before that.

The story was that he had hidden a great treasure, and that he could dip into it whenever he wished, and that he had bought property, a good deal of it. It was true that he had sailed to Quebec City or Montreal whenver he desired-even down to Boston or New York to buy whatever he wished. But I knew nothing of any treasure, nothing at all. If he had left any behind it was so well hiddden that no one knew where it could be.

My father had shrugged off the stories. "Nonsense!" he would say. "Think nothing of treasure or stories of treasure. You will have in this world just what you earn ... and save. Remember that. Do not waste your life in a vain search for treasure that may not exist."

"There is no treasure," I said to her. "It is all a silly story."

"But he had money!" she protested. "He was fabulously rich!"

"And he spent it," I said. "If you want me it shall be as I am, a man with a good craft who can make a good living."

She was scornful. "A good living! Do you think that is all I want? Henry can give me everything! A beautiful home, travel, money to spend, beautiful clothes ...."

"Take him then," I had told her. "Take him, and be damned!"

Here and there a log had sunk deep, leaving a cleft into which a suddenly plunged foot could mean a broken leg, and on either side of the swamp ... well, some said it was bottomless. Horses had sunk there, never to be seen again-and men, also.

My father's house lay several days behind me, back of a shoulder on the Quebec shore above the Gulf of St. Lawrence. For days I had been walking southward. An owl glided past with great, slow wings, and out in the swamp some unseen creature moved, seemed to pause, listen.

Was that a step behind me?

Astride a gap between logs, I paused, half turned to look.

Nothing. I must have been mistaken. Yet, I had heard something.

My shoulders ached from the burden of my tools. Straining my eyes in hte darkness, I looked for a place to stop, any place which to rest, if ever so briefly. And then I saw a wide stump from which a tree had been sawed, a full six feet in diameter. The tree cut from it lay in the swamp close by, half sunk.

With my left hand I swung my tools to the stump, keeping the rifle in my right, ready for use. This was a wild place. There were few travelers, and fewer still were honest men. Young I might be, but not trusting.

For the first time I was leaving my home, going south from Canada into the United States. Westward, it was said, they were building, and we are builders, we Talons.

There was a time when at least one of the family had been a pirate. He had been a privateer in the waters of the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and the Red Sea, but mostly off the Coromandel and Malabar coasts of India. He'd done well, too, or so it was said. I'd seen none of the treasure he was said to have brought away.

What was that? I half rose from my seat on the stump, then settled back, holding my rifle in both hands.

It was cold, growing colder.

Behind me, on the Gaspé, I had left my father's cottage and the good will of at least some of my neighbors. My father was gone. My mother had died when I was yet a young boy, and I had no sweetheart.

Of course, there had been a girl. We had roamed the fields together as children, danced together, even talked of marriage. That was before a man far wealthier than I had come to see her father. To be wealthier than I was not difficult, for I had only the cottage inherited from my father, a few acres adjoining, a small fishing boat, and my trade. And she was ambitious.

The other man was a merchant with many acres, a three-masted schooner trading along the coast, and a store. He was a landed, a moneyed man, and, as I have said, she was ambitious.

She had come to our meeting place one last time. At once she was different. There was no fooling about on this day, for she was very serious. "Jean!" She pronounced it zhan, as was correct, but with an inflection that was her own. "My father wants me to marry Henry Barboure."

It took a moment for me to understand. Henry Barboure was nearly forty, twice as old as I, and a respected, successful man, although I'd heard it said that he was close-fisted and a hard man to deal with.

"You are not going to?" I protested.

"I must, unless ... unless ...."

"Unless what?"

"Jean, do you know where the treasure is? I mean all that gold the old man left? He was your great-grandfather, wasn't he? The pirate?"

"It was further back than that, " I said. "And anyway, he left no gold. None that I know of."

She came closer to me. "I know it is a family secret. I know it's always been a secret, a mystery, but Jean ..... if we had all that gold ... well, Father would never think of asking me to marry Henry. He always told me you'd know where it was, and you could get some of it, whenever you liked."

So that was it. The gold. Of course, I knew the stories. They had been a legend in the Gaspé since the first old man's time. He had been one of the first to settle on what was then a lonely, almost uninhabited coast. He had built a strong stone castle-burned by the British during one of their raids on the coast many years after, and attacked many times before that.

The story was that he had hidden a great treasure, and that he could dip into it whenever he wished, and that he had bought property, a good deal of it. It was true that he had sailed to Quebec City or Montreal whenver he desired-even down to Boston or New York to buy whatever he wished. But I knew nothing of any treasure, nothing at all. If he had left any behind it was so well hiddden that no one knew where it could be.

My father had shrugged off the stories. "Nonsense!" he would say. "Think nothing of treasure or stories of treasure. You will have in this world just what you earn ... and save. Remember that. Do not waste your life in a vain search for treasure that may not exist."

"There is no treasure," I said to her. "It is all a silly story."

"But he had money!" she protested. "He was fabulously rich!"

"And he spent it," I said. "If you want me it shall be as I am, a man with a good craft who can make a good living."

She was scornful. "A good living! Do you think that is all I want? Henry can give me everything! A beautiful home, travel, money to spend, beautiful clothes ...."

"Take him then," I had told her. "Take him, and be damned!"