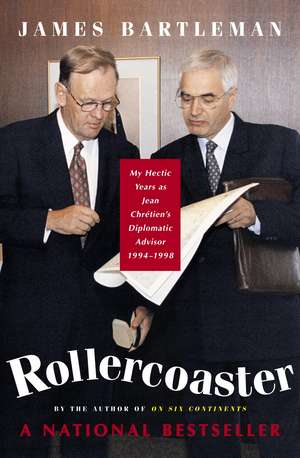

Rollercoaster: My Hectic Years as Jean Chretien's Diplomatic Advisor, 1994-1998

Autor James K. Bartlemanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2007

He was involved in deadly serious crisis management, accompanying Chrétien to all the world’s hot spots – dodging bullets in Sarajevo, and trying to avoid war in the Spanish trawler incident. Not to mention dealing with Premier Li of China on an official visit encountering protestors in Montreal and shouting, “I am departing immediately. Never have I and my country been so humiliated.”

Which leader at the G7 Summit in Halifax passed out drunk in the hotel elevator? What did Jean Chrétien do to set White House aides threatening, “the next time there’s a referendum, we will support the separatists”? And why did Fidel Castro grab our author, shaking him and snarling, “I hope you are satisfied, Bartleman”? It’s all in this lively book.

Every major world crisis of these years is represented here, and every region of the world. You’ll be amazed at how widely Chrétien and Bartleman travelled and how much top-level action they experienced. Canadian foreign policy has never seemed so exciting. Or so funny (as when the angry Japanese prime minister’s Ottawa visit was marred by a health problem officially described as “soft poo”). A candid, witty, eye-opening book about foreign affairs at the top.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 105.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.21€ • 21.16$ • 16.72£

20.21€ • 21.16$ • 16.72£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771010958

ISBN-10: 0771010958

Pagini: 358

Ilustrații: 4 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 143 x 222 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Douglas Gibson

ISBN-10: 0771010958

Pagini: 358

Ilustrații: 4 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 143 x 222 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Douglas Gibson

Notă biografică

James K. Bartleman is the author of On Six Continents and the new memoir Raisin Wine. He is the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario.

Extras

It’s March,1995, and Canada and Spain are close to declaring war on each other. James Bartleman, as the Prime Minister’s Foreign Policy Advisor, is trying to prevent the war from breaking out:

The OK Corral

When the Canadian and Spanish armadas squared off on the Grand Banks the weather could not have been better for a fight. Winds were low, seas were moderate, and visibility was fair. In one corner was the Canadian fleet, composed of a motley collection of civilian and military ships operating under a confusing variety of legal authorities. The Fisheries patrol boats, Cape Roger, Cygnus, and Chebucto, were manned by personnel possessing peace-officer status and legally entitled to use force to effect arrests in accordance with Canadian law. Two Coast Guard vessels, the supply ship J. E. Bernier and the icebreaker Sir John Franklin, were in the line of battle ready to take on the might of Spain. Their personnel, who were not peace officers, probably wondered what they were doing in the middle of a possible shootout out in the Atlantic. HMCS Gatineau, which had replaced HMCS Terra Nova as military backup, was steaming towards the zone of possible action from its hull-down position within Canada’s two-hundred-mile zone. A second frigate, HMCS Nipigon, was preparing to set sail from Halifax to join the battle. By this time, keeping up the pressure on the Spanish military, the head of Canada’s navy served notice to his Spanish counterpart that he intended to deploy submarines in the contested zone. Then on Good Friday, the Chief of Defence, after obtaining Cabinet approval, issued instructions to the commanders of the frigates to use deadly force to defend any Canadian civilian vessel threatened by a Spanish warship as it sought to make an arrest.

In the other corner was “the enemy” — a Spanish armada composed of eighteen factory trawlers under orders from their owners to carry on fishing. Backing them up were two small Spanish navy patrol boats, Vigia and Centinella, whose normal role was inspecting fishing boats in Spanish coastal waters. Another small naval patrol boat, Atalaya, was on its way from Spain to join the fray. All three had been similarly ordered to use deadly force to protect the Spanish fishing fleet. The Kommander Amalie was also in the area, but not expected to participate in the engagement.

To make sure that there was no possible misunderstanding regarding our intentions, the Canadian navy contacted the Spanish navy to say that the Canadian frigates had been authorized to use deadly force against the Vigia, Centinella, and Atalaya. I called my old friend, Ambassador Pardos, to tell him that Canada intended to arrest another Spanish fishing vessel the next morning. Should the Spanish patrol boats intervene, I said, our frigates had orders to open fire on them. I don’t believe he thumped his chest this time.

Next I telephoned Canada’s ambassador in Madrid, David Wright, using an open telephone line that I hoped was being monitored by the Spanish Intelligence Service. I told David that the Canadian government had decided to arrest another fishing vessel on Easter Saturday unless Spain changed its mind and accepted the deal it had just disowned in Brussels. We expected that the Spanish naval vessels on the Grand Banks would intervene to try to stop the arrest. HMCS Gatineau was almost at its action station and would shortly be joined by HMCS Nipigon. Cabinet had met, I told him, and had given authority for the navy to use deadly force. In lay terms, the captains of the Canadian warships were expected to open fire, without further recourse to headquarters for instructions, on the Spanish naval vessels to protect the Canadian fisheries patrol boats. David understood that I was also passing a message to the Spanish authorities and made no comment.

Everything that I told the two ambassadors was true. We were heading for a confrontation in which young Canadians and Spaniards would probably die. I wanted to be sure that the Spaniards got the message, so that they could back down in time. They did, but some of us found the Spanish capitulation, when it came, difficult to accept, and were reluctant to take yes for an answer.

The Final Hours

Early on Easter Saturday morning, Deep Throat called to say that the European Union ambassadors had met in an emergency session throughout the night. Spain had come around and a negotiated settlement was now ours for the asking. The European ambassadors would be in touch with Ambassador Roy after they got some sleep.

“But please don’t do anything foolish such as arresting another Spanish fishing vessel today,” he advised. “Otherwise the end-game being played out in Brussels will disappear and the showdown will be between Canada and Spain alone on the high seas.”

The peace camp strongly favoured waiting for a few hours before making the arrest. The war camp disagreed and pushed hard to follow through with plans for early morning action. The prime minister opted to authorize Ambassador Roy to attend a meeting of European Union ambassadors in a final effort to conclude a deal. We would soon see if Deep Throat was right when he said that Spain had been brought on side. Our ambassador’s instructions were to accept inconsequential changes if need be, but not to agree to any outrageous demands of the Spaniards for more fish. Happily the Europeans were ready to agree, and Ambassador Roy was soon able to send a draft text to us. We reviewed the text, obtained approval from the prime minister, and told our man in Brussels that the government could accept the final package. Approval, he told us, would come from Madrid within two hours; everyone, he said, even the hard-line Spanish ambassador in Brussels, was now confident that the fish war was over.

But we had not reckoned on the continued obstinacy — there might be a harsher word — of the war camp. A contact in Defence sympathetic to the peace camp telephoned me to say that a radio operator on one of the Canadian frigates had intercepted radio traffic between the Fisheries patrol boats. The war camp, in one final outburst of bad judgement and without consulting anyone else, had sent instructions to the skippers of the civilian fleet to make one last charge through the Spanish fleet. Someone had watched too many bullfighter movies. Deeply regretting my initiative in proposing that an icebreaker be added to Tobin’s fleet, I frantically called the prime minister, who countermanded the hare-brained order. Ambassador Roy then telephoned to say that Madrid had acquiesced; the Turbot War was over.

The government’s central goal, the saving of the turbot stock, was accomplished even if Spain, bitter and humiliated, would make us pay a price by throwing roadblock after roadblock into Canada’s efforts to forge closer ties with Europe for years to come. Brian Tobin emerged as “Captain Canada,” his popularity such that he would leave federal politics in short order to be crowned premier of Newfoundland. Bill Rowat would follow Tobin to Newfoundland to apply his considerable management skills to the Labrador Falls hydro-power project, and later would become president of the Railways Association of Canada. Gordon Smith would continue serving his country with distinction until his retirement from the foreign service. Jacques Roy would be named ambassador to France. As for me, I would lick my wounds, re-establish working relations with Jocelyne Bourgon, and focus on the next crisis looming on the horizon — the degenerating situation in the former Yugoslavia.

From the Hardcover edition.

The OK Corral

When the Canadian and Spanish armadas squared off on the Grand Banks the weather could not have been better for a fight. Winds were low, seas were moderate, and visibility was fair. In one corner was the Canadian fleet, composed of a motley collection of civilian and military ships operating under a confusing variety of legal authorities. The Fisheries patrol boats, Cape Roger, Cygnus, and Chebucto, were manned by personnel possessing peace-officer status and legally entitled to use force to effect arrests in accordance with Canadian law. Two Coast Guard vessels, the supply ship J. E. Bernier and the icebreaker Sir John Franklin, were in the line of battle ready to take on the might of Spain. Their personnel, who were not peace officers, probably wondered what they were doing in the middle of a possible shootout out in the Atlantic. HMCS Gatineau, which had replaced HMCS Terra Nova as military backup, was steaming towards the zone of possible action from its hull-down position within Canada’s two-hundred-mile zone. A second frigate, HMCS Nipigon, was preparing to set sail from Halifax to join the battle. By this time, keeping up the pressure on the Spanish military, the head of Canada’s navy served notice to his Spanish counterpart that he intended to deploy submarines in the contested zone. Then on Good Friday, the Chief of Defence, after obtaining Cabinet approval, issued instructions to the commanders of the frigates to use deadly force to defend any Canadian civilian vessel threatened by a Spanish warship as it sought to make an arrest.

In the other corner was “the enemy” — a Spanish armada composed of eighteen factory trawlers under orders from their owners to carry on fishing. Backing them up were two small Spanish navy patrol boats, Vigia and Centinella, whose normal role was inspecting fishing boats in Spanish coastal waters. Another small naval patrol boat, Atalaya, was on its way from Spain to join the fray. All three had been similarly ordered to use deadly force to protect the Spanish fishing fleet. The Kommander Amalie was also in the area, but not expected to participate in the engagement.

To make sure that there was no possible misunderstanding regarding our intentions, the Canadian navy contacted the Spanish navy to say that the Canadian frigates had been authorized to use deadly force against the Vigia, Centinella, and Atalaya. I called my old friend, Ambassador Pardos, to tell him that Canada intended to arrest another Spanish fishing vessel the next morning. Should the Spanish patrol boats intervene, I said, our frigates had orders to open fire on them. I don’t believe he thumped his chest this time.

Next I telephoned Canada’s ambassador in Madrid, David Wright, using an open telephone line that I hoped was being monitored by the Spanish Intelligence Service. I told David that the Canadian government had decided to arrest another fishing vessel on Easter Saturday unless Spain changed its mind and accepted the deal it had just disowned in Brussels. We expected that the Spanish naval vessels on the Grand Banks would intervene to try to stop the arrest. HMCS Gatineau was almost at its action station and would shortly be joined by HMCS Nipigon. Cabinet had met, I told him, and had given authority for the navy to use deadly force. In lay terms, the captains of the Canadian warships were expected to open fire, without further recourse to headquarters for instructions, on the Spanish naval vessels to protect the Canadian fisheries patrol boats. David understood that I was also passing a message to the Spanish authorities and made no comment.

Everything that I told the two ambassadors was true. We were heading for a confrontation in which young Canadians and Spaniards would probably die. I wanted to be sure that the Spaniards got the message, so that they could back down in time. They did, but some of us found the Spanish capitulation, when it came, difficult to accept, and were reluctant to take yes for an answer.

The Final Hours

Early on Easter Saturday morning, Deep Throat called to say that the European Union ambassadors had met in an emergency session throughout the night. Spain had come around and a negotiated settlement was now ours for the asking. The European ambassadors would be in touch with Ambassador Roy after they got some sleep.

“But please don’t do anything foolish such as arresting another Spanish fishing vessel today,” he advised. “Otherwise the end-game being played out in Brussels will disappear and the showdown will be between Canada and Spain alone on the high seas.”

The peace camp strongly favoured waiting for a few hours before making the arrest. The war camp disagreed and pushed hard to follow through with plans for early morning action. The prime minister opted to authorize Ambassador Roy to attend a meeting of European Union ambassadors in a final effort to conclude a deal. We would soon see if Deep Throat was right when he said that Spain had been brought on side. Our ambassador’s instructions were to accept inconsequential changes if need be, but not to agree to any outrageous demands of the Spaniards for more fish. Happily the Europeans were ready to agree, and Ambassador Roy was soon able to send a draft text to us. We reviewed the text, obtained approval from the prime minister, and told our man in Brussels that the government could accept the final package. Approval, he told us, would come from Madrid within two hours; everyone, he said, even the hard-line Spanish ambassador in Brussels, was now confident that the fish war was over.

But we had not reckoned on the continued obstinacy — there might be a harsher word — of the war camp. A contact in Defence sympathetic to the peace camp telephoned me to say that a radio operator on one of the Canadian frigates had intercepted radio traffic between the Fisheries patrol boats. The war camp, in one final outburst of bad judgement and without consulting anyone else, had sent instructions to the skippers of the civilian fleet to make one last charge through the Spanish fleet. Someone had watched too many bullfighter movies. Deeply regretting my initiative in proposing that an icebreaker be added to Tobin’s fleet, I frantically called the prime minister, who countermanded the hare-brained order. Ambassador Roy then telephoned to say that Madrid had acquiesced; the Turbot War was over.

The government’s central goal, the saving of the turbot stock, was accomplished even if Spain, bitter and humiliated, would make us pay a price by throwing roadblock after roadblock into Canada’s efforts to forge closer ties with Europe for years to come. Brian Tobin emerged as “Captain Canada,” his popularity such that he would leave federal politics in short order to be crowned premier of Newfoundland. Bill Rowat would follow Tobin to Newfoundland to apply his considerable management skills to the Labrador Falls hydro-power project, and later would become president of the Railways Association of Canada. Gordon Smith would continue serving his country with distinction until his retirement from the foreign service. Jacques Roy would be named ambassador to France. As for me, I would lick my wounds, re-establish working relations with Jocelyne Bourgon, and focus on the next crisis looming on the horizon — the degenerating situation in the former Yugoslavia.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Candid and engaging.”

— Globe and Mail

“A real treat.”

— Winnipeg Free Press

“The reader gets a shotgun seat on a tumultuous ride.”

— Ottawa Hill Times

— Globe and Mail

“A real treat.”

— Winnipeg Free Press

“The reader gets a shotgun seat on a tumultuous ride.”

— Ottawa Hill Times