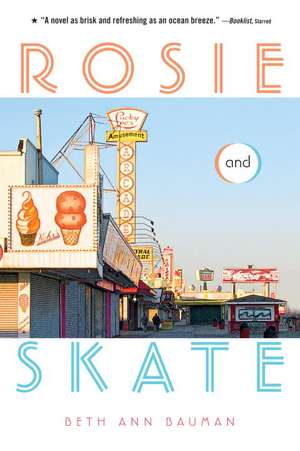

Rosie and Skate

Autor Beth Ann Baumanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2011 – vârsta de la 14 ani

It's off-season at the Jersey shore. The boardwalk belongs to the locals—including Rosie and Skate, sisters who are a year apart in age but couldn't be more different. Rosie's fifteen, shy, and waiting for her life to begin. Skate, sixteen, is tougher and knows what she wants. Readers will be totally caught up as the sisters' story plays out within the embrace of their quirky, warmhearted community.

Preț: 79.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 119

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.19€ • 16.24$ • 12.66£

15.19€ • 16.24$ • 12.66£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385737364

ISBN-10: 038573736X

Pagini: 217

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: WENDY LAMB BOOKS

ISBN-10: 038573736X

Pagini: 217

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: WENDY LAMB BOOKS

Notă biografică

Beth Ann Bauman is the author of a short story collection for adults, Beautiful Girls, and a recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship. Growing up, she spent summers on the Jersey shore. She lives in New York City.

Extras

Rosie

My dad's a nice drunk. There is such a thing. I know how that sounds, but honestly he's a good person. My sister, Skate, is going to give you a different story, but I want you to hear my side too.

Before our dad went to jail three weeks ago, one of his favorite places was the old faded couch on the sun porch, where he'd lie with sandy feet, clutching his bottle of Old Crow whiskey, gurgling to himself with a dreamy smile. If he saw me standing above him, staring down at him, he'd give me a little finger wave. "Lovely to see ya, Rosie girl." Or sometimes he'd look at me and not see me at all, but he'd smile all the same. You see what I mean? Screwed-up, but nice.

Of course this isn't true of every drunk. This is what I've learned from coming to these meetings for the past three weeks: some drunks have a mean streak. The guy sitting across from me once had his nose broken when his dad blew a fuse. And some drunks are crybabies, I learned from a girl with a nose ring whose mom schleps around the house in a dirty bathrobe, moaning about the past. And some are hopeless, like the dad who gets out of rehab and then starts drinking the very next day. My dad--nice drunk that he is--is also hopeless, Skate says. Last time he went to rehab for six weeks and started drinking again the very same afternoon he came home. And some are sneaky; they go to work, pay the mortgage and gas bills, make spaghetti and meatballs, but they live in a boozy fog, hiding their bottles in the toilet tank, the hamper, the fireplace.

Skate hates these meetings. Drama Queen, she calls them. "Please," she says. "All that yakking. All that whining." That's why she isn't here yet. I'm worried she won't come. I just come. I show up here in the basement of St. Joseph By the Sea and sit on a folding chair and eat Gus's cookies out of a shoe box lined with foil. Skechers, size 12. Gus is in college and runs the meetings. He makes butter cookies in the shapes of moons and stars. His mom gave him the cookie cutters, he told me. The cookies are dented and crumbly but sweet, and we all wind up wearing crumbs down the front of our shirts. So I come here every week and eat cookies and wear crumbs and listen to other kids whose parents are drunks.

Gus drags a chair over to the circle and starts the meeting. But I can barely pay attention to what he's saying. I sip a cup of cherry cola and stare at the door, willing it to swing open and blow in my sister--with her long wild hair and her skateboard under her arm. She's always late, if she comes at all. She thinks our dad is a big loser.

"My dad guzzles vodka down the bay," Nick says. "Drinks it in a teacup. Like he's some regular guy." Nick is a quiet kid from my homeroom, tall and slouchy with hair falling into his face. "The old dude sits there sipping vodka, getting up and down to refill his cup from the bottle he keeps hidden in cattails. Drinks till he passes out. Tips right over into the sand. Happens between nine and nine-thirty every night, like clockwork." Nick looks out at the room with a little frown and hooks his stringy hair behind his ears. He has the daintiest pink ears I've ever seen on a person. "So we head down there. My brothers grab his arms and my sister and I each grab a leg and we hoist him into a wheelbarrow and wheel him home."

"Why do you do that?" Gus asks.

"Why?" Nick says.

"Why?" Gus says calmly. Nothing ever rattles Gus. He has a nice sad smile, like he expects stuff to be totally screwed-up, even though he wishes it weren't. Gus is built like a wrestler--short but muscle-y, and he's got this spiky crew cut he runs his hand over when he's thinking hard.

"But we can't leave him there!" Nick blurts out, his little ears turning pinker.

"Why not?" Gus says.

And while I'm listening and not staring at the door, it opens. And here is Skate, carrying her board. She flashes a smile at the room and drops into the seat next to me. "Hey, Ro," she whispers, reaching for a cookie. She's wearing torn Levi's, fishnets, Keds, and a washed-out black T-shirt decorated with a tiny strawberry. Her long hair is beaded with drops of water.

"Where were you?" I whisper back, reaching for a cookie too.

"Let me get this straight," Nick says. "You think we should leave him there? Lying in the sand? Stupid drunk? For all the neighbors to see?"

"Yes," Gus says.

Nick stares at him. "Are you crazy?"

Gus smiles. "Occasionally. But really, why not leave him there?"

"Well, it's embarrassing!" A few of us nod in agreement.

"But it's your dad's problem, not yours," Gus says.

"But he's my dad, and I don't want the whole frickin' neighborhood to see him passed out on the sand."

"They probably see you loading him into the wheelbarrow."

"Maybe not," Nick mumbles. "Maybe not."

"If it happens almost every night, they probably know," Gus says.

Poor Nick. If I were him I'd probably hoist my dad into a wheelbarrow too. I smile at him, but he's staring at the floor, his stringy hair falling into his face.

Our dad didn't pass out in the yard or at the beach or anything like that, but even so, drinking wrecked him. He went to Walgreens in his raincoat and slippers and shuffled down the aisles, loading the lining of his coat with crazy stuff: a can opener, coconut tanning oil, nail clippers, panty hose, potpourri. Then he stood in line, and when the cashier cracked a roll of quarters against the side of the register, he reached in and grabbed a stack of twenties. "Thank you, my dear," he said. There was no security guard working that day, and when the police caught up to him, he was sitting on the curb a block away, having just trimmed his toenails, rubbing tanning oil onto his face.

My dad's a nice drunk. There is such a thing. I know how that sounds, but honestly he's a good person. My sister, Skate, is going to give you a different story, but I want you to hear my side too.

Before our dad went to jail three weeks ago, one of his favorite places was the old faded couch on the sun porch, where he'd lie with sandy feet, clutching his bottle of Old Crow whiskey, gurgling to himself with a dreamy smile. If he saw me standing above him, staring down at him, he'd give me a little finger wave. "Lovely to see ya, Rosie girl." Or sometimes he'd look at me and not see me at all, but he'd smile all the same. You see what I mean? Screwed-up, but nice.

Of course this isn't true of every drunk. This is what I've learned from coming to these meetings for the past three weeks: some drunks have a mean streak. The guy sitting across from me once had his nose broken when his dad blew a fuse. And some drunks are crybabies, I learned from a girl with a nose ring whose mom schleps around the house in a dirty bathrobe, moaning about the past. And some are hopeless, like the dad who gets out of rehab and then starts drinking the very next day. My dad--nice drunk that he is--is also hopeless, Skate says. Last time he went to rehab for six weeks and started drinking again the very same afternoon he came home. And some are sneaky; they go to work, pay the mortgage and gas bills, make spaghetti and meatballs, but they live in a boozy fog, hiding their bottles in the toilet tank, the hamper, the fireplace.

Skate hates these meetings. Drama Queen, she calls them. "Please," she says. "All that yakking. All that whining." That's why she isn't here yet. I'm worried she won't come. I just come. I show up here in the basement of St. Joseph By the Sea and sit on a folding chair and eat Gus's cookies out of a shoe box lined with foil. Skechers, size 12. Gus is in college and runs the meetings. He makes butter cookies in the shapes of moons and stars. His mom gave him the cookie cutters, he told me. The cookies are dented and crumbly but sweet, and we all wind up wearing crumbs down the front of our shirts. So I come here every week and eat cookies and wear crumbs and listen to other kids whose parents are drunks.

Gus drags a chair over to the circle and starts the meeting. But I can barely pay attention to what he's saying. I sip a cup of cherry cola and stare at the door, willing it to swing open and blow in my sister--with her long wild hair and her skateboard under her arm. She's always late, if she comes at all. She thinks our dad is a big loser.

"My dad guzzles vodka down the bay," Nick says. "Drinks it in a teacup. Like he's some regular guy." Nick is a quiet kid from my homeroom, tall and slouchy with hair falling into his face. "The old dude sits there sipping vodka, getting up and down to refill his cup from the bottle he keeps hidden in cattails. Drinks till he passes out. Tips right over into the sand. Happens between nine and nine-thirty every night, like clockwork." Nick looks out at the room with a little frown and hooks his stringy hair behind his ears. He has the daintiest pink ears I've ever seen on a person. "So we head down there. My brothers grab his arms and my sister and I each grab a leg and we hoist him into a wheelbarrow and wheel him home."

"Why do you do that?" Gus asks.

"Why?" Nick says.

"Why?" Gus says calmly. Nothing ever rattles Gus. He has a nice sad smile, like he expects stuff to be totally screwed-up, even though he wishes it weren't. Gus is built like a wrestler--short but muscle-y, and he's got this spiky crew cut he runs his hand over when he's thinking hard.

"But we can't leave him there!" Nick blurts out, his little ears turning pinker.

"Why not?" Gus says.

And while I'm listening and not staring at the door, it opens. And here is Skate, carrying her board. She flashes a smile at the room and drops into the seat next to me. "Hey, Ro," she whispers, reaching for a cookie. She's wearing torn Levi's, fishnets, Keds, and a washed-out black T-shirt decorated with a tiny strawberry. Her long hair is beaded with drops of water.

"Where were you?" I whisper back, reaching for a cookie too.

"Let me get this straight," Nick says. "You think we should leave him there? Lying in the sand? Stupid drunk? For all the neighbors to see?"

"Yes," Gus says.

Nick stares at him. "Are you crazy?"

Gus smiles. "Occasionally. But really, why not leave him there?"

"Well, it's embarrassing!" A few of us nod in agreement.

"But it's your dad's problem, not yours," Gus says.

"But he's my dad, and I don't want the whole frickin' neighborhood to see him passed out on the sand."

"They probably see you loading him into the wheelbarrow."

"Maybe not," Nick mumbles. "Maybe not."

"If it happens almost every night, they probably know," Gus says.

Poor Nick. If I were him I'd probably hoist my dad into a wheelbarrow too. I smile at him, but he's staring at the floor, his stringy hair falling into his face.

Our dad didn't pass out in the yard or at the beach or anything like that, but even so, drinking wrecked him. He went to Walgreens in his raincoat and slippers and shuffled down the aisles, loading the lining of his coat with crazy stuff: a can opener, coconut tanning oil, nail clippers, panty hose, potpourri. Then he stood in line, and when the cashier cracked a roll of quarters against the side of the register, he reached in and grabbed a stack of twenties. "Thank you, my dear," he said. There was no security guard working that day, and when the police caught up to him, he was sitting on the curb a block away, having just trimmed his toenails, rubbing tanning oil onto his face.

Recenzii

Starred Review, Kirkus Reviews, August 15, 2009:

"The novel expertly captures the ever-hopeful ache of adolescents longing for love, stability, and certainty."

Starred Review, Booklist, October 1, 2009:

"This is a novel as brisk and refreshing as an ocean breeze."

Review, New York Times Books Review, January 17, 2010:

"In capturing the miscues of first love and shifting family dynamics, Rosie and Skate is as sharp as a splinter on the boardwalk."

From the Hardcover edition.

"The novel expertly captures the ever-hopeful ache of adolescents longing for love, stability, and certainty."

Starred Review, Booklist, October 1, 2009:

"This is a novel as brisk and refreshing as an ocean breeze."

Review, New York Times Books Review, January 17, 2010:

"In capturing the miscues of first love and shifting family dynamics, Rosie and Skate is as sharp as a splinter on the boardwalk."

From the Hardcover edition.