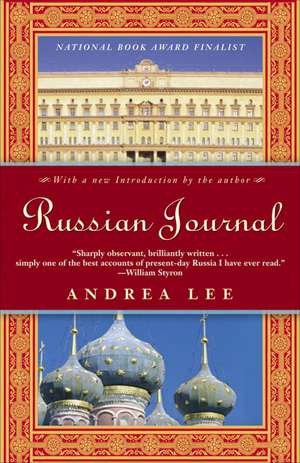

Russian Journal

Autor Andrea Leeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2006

At age twenty-five, Andrea Lee joined her husband, a Harvard doctoral candidate in Russian history, for his eight months’ study at Moscow State University and an additional two months in Leningrad. Published to enormous critical acclaim in 1981, Russian Journal is the award-winning author’s penetrating, vivid account of her everyday life as an expatriate in Soviet culture, chronicling her fascinating exchanges with journalists, diplomats, and her Soviet contemporaries. The winner of the Jean Stein Award from the National Academy of Arts and Letters–and the book that launched Lee’s career as a writer–Russian Journal is a beautiful and clear-eyed travel-writing classic.

“[Lee] takes us wherever she is, conveying a feeling of place and atmosphere that is the mark of real talent.”

–The Washington Post Book World

“A book of very great charm . . . [Lee] records what she saw and heard with unassuming delicacy and exactness.”

–Newsweek

Preț: 114.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.99€ • 22.93$ • 18.28£

21.99€ • 22.93$ • 18.28£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 20 martie-03 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812976656

ISBN-10: 0812976657

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812976657

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Extras

Chapter 1

Arrival

AUGUST 3

The tower in which we will live for most of the next ten months is one of the landmarks of Moscow, an absurd thirty-two-story wedding cake of gray and red granite, set above the city in the Lenin Hills. This titanic building, the main dormitory of Moscow State University, is a monument of the pompous and energetic style of architecture nicknamed “Stalin Gothic.” Seen from a distance, it suggests a Disney version of a ziggurat; its central spire, like the Kremlin towers, holds a blinking red star. Inside, as in a medieval fortress, there is everything necessary to sustain life in case of siege: bakeries, a dairy store, a fruit and vegetable store, a pharmacy, a post office, magazine kiosks, a watch-repair stand—all this in addition to classrooms, and student rooms, and cafeterias. On the outside, it bristles with a daft excess of decoration that is a strange twentieth-century mixture of Babylonian, Corinthian, and Slavic: there are outsized bronze flags and statues, faïence curlicues, wrought-iron sconces—even a vast reflecting pool decorated with metal water lilies the size of small cabbages. As I climb the endless stairs and negotiate the labyrinth of fusty-smelling hallways, I feel dwarfed and apprehensive, a human being lost in a palace scaled for giants.

I came to this odd new home with my husband on a summer evening two days ago, when exhaustion from long-distance travel gave every new sight the mysterious simplicity and resonance of a dream. I had my first glimpse of the Soviet Union as we broke through a cloud barrier near Sheremetyevo Airport, and found ourselves flying low over a forest of birch and evergreen, dotted with countless small ponds. There was an almost magical lushness and secrecy about this flattish northern landscape that I found powerfully attractive; suddenly I remembered that my earliest visions of Russia were of an infinite forest, dark as any forest that stretches through a child’s imagination, and peopled by swan maidens, hunter princes, fabulous bears, and witches who lived in huts set on chicken legs. Tied to Russia by no claims of blood or tradition, I still felt, while very young, an obscure attraction to this country that I knew only from its violent, highly colored folklore; its music, through which ran a similar vein of extravagance; and the dark political comments of adults. It seemed to me to be a mysterious counterweight to the known world of America—a country, like the land at the back of the north wind, in which life ran backward and the fantastic was commonplace.

Our disembarkment and passage through customs at Sheremetyevo were standard chaos, involving a long, dazed wait in a crowded room traversed from time to time by hot breezes smelling sweetly of cut grass. Only one memory remains with me from those hours: the sight of a Pioneer* excursion group of twenty small girls who seemed, by their Asiatic faces and straight black hair, to be Siberian. They all wore the blue shorts, white shirts, and red neckerchiefs that I had seen in pictures, as well as ornately curled hair bows that gave them a queer geisha look, and as I studied them with the dreamy precision of fatigue, all twenty stared back at me with an avid, unadorned curiosity. Standing beyond the customs barrier was a young man who introduced himself in English as Grigorii, a journalism student sent to meet us by the university’s office of foreign affairs. Grigorii was a dark-haired young man in his twenties, with very small eyes behind enormous round glasses and a pinched, rather gnomish body in a large, baggy suit; the impression he gave was that he had melted down slightly inside his clothing. He led us outside to a black Volga, a Soviet car that looks like a cross between a Rambler and a Plymouth. A short-legged driver, wearing a checked cap pulled down very far over his ears, stowed our bags, and soon we were speeding down a road with the vaguely horrifying sense of freedom one feels only when going through absolutely strange territory in a strange car. It was dark by now, and the smell of fields and forest rushed in through the windows. Grigorii had discovered that we both spoke Russian, and had grown garrulous. “So you are a student of Russian history?” he was saying to Tom. “I myself am extremely interested in American history—especially in your Civil War. Two years ago I even wrote a paper on the Great Barbecue.”

“The what?” asked Tom.

“The Great Barbecue—the turning point of the Reconstruction period. Don’t tell me you haven’t heard of it!” (Grigorii pronounced the word “barbecue” with the gleeful relish of a Frenchman saying “Marlboro.”)

“I haven’t,” said Tom, and as the car slid through the darkness, Grigorii illuminated for us this lost part of American history, mentioning feudal remnants, the industrial bourgeoisie, and the struggle of the working class. Listening to his small, dry, pedantic voice mention names and places I’d never heard of, I wondered what Marxist looking-glass we’d stepped through. Where on earth were we? Was he talking about the same America we had just left?

When the monstrous silhouette of the university tower appeared on the skyline, Grigorii paused to point it out proudly. “Impressive, isn’t it?” he said. “It’s the most luxurious dormitory in the Soviet Union—every year hundreds of tourists come to visit it. It’s a city block in circumference; some other time I will give you the figures on its height and number of windows. I’m sorry that we won’t be passing the reflecting pool tonight, but there is a very handsome giant barometer that I will show you. I feel very lucky to live there. We’ll be neighbors, so to speak!”

“Hurrah!” I whispered to Tom, and he dug his elbow into my ribs. Then we sat silently as the black tower grew larger against the sky.

Our arrival meant passing through a gatehouse, climbing a great many stairs, crossing a chilly marble hall, and threading through a maze of corridors on a path that led at last to a long ride in an elevator, and some kind of fuss with an old woman over a key. Although it was only about nine o’clock in the evening, a charmed stillness seemed to reign in the dormitory; we saw very few students. Instead, there seemed to be inordinate numbers of babushki—old women—in semi-official posts, knitting and nodding in dark corners like watchful beldames out of a Grimms tale. The babushka of the keys, a tiny creature with a fierce squint under a cowled white shawl, watched us struggle with the door to our room and then turned to whisper portentously to a still smaller companion, Ischo Amerikantsy—More Americans.

When Grigorii left us, we flicked a switch, and in the sudden bright light, faced our living quarters for the year. They were what Russians call a blok—a minute suite consisting of two rooms about six feet by ten feet each, a tiny entryway, and a pair of cubicles containing, between them, a toilet, a shower and washstand, and several large, indolent cockroaches. The two main rooms were painted the dispiriting beige and green of institutional rooms around the world, and furnished, rather nicely, with varnished chairs, tables, bookcases, and two single beds. (I’ve since discovered that our rooms represent great luxury, since Russian students in the same building often live four and six to such quarters.) Each room held a radio that tuned in to only one station—Radio Moscow—and at this particular moment, news was being broadcast by a woman with an excited, throaty voice. “Today,” she said, “the Party Government delegation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, led by Comrades Le Duan and Pham Van Dong visited the Kirovsky factory in Leningrad . . . In front of the monument to V. I. Lenin in Factory Square, there took place a meeting of Soviet-Vietnamese friendship . . . The Leningraders arrived at the meeting with flowers, red flags, and signs in honor of the unbreakable friendship . . . The people gathering together greeted the emissaries of the heroic Vietnamese people with warm applause . . .”

The news went off, and on came a medley of Komsomol songs delivered stalwartly by what sounded like an entire nation of ruddy-cheeked young patriots. “You can’t turn this thing off,” said Tom, fiddling with the radio knob. Indeed, like one of Orwell’s telescreens, our official radios could be turned down to inaudible, but never turned off. I began to giggle hysterically, and to calm myself, walked over to the window, from which I could see, illuminated by a spotlight on one of the pediments of the building, a gigantic bronze flag.

A bit later, in one of the fits of witless energy that sometimes replace exhaustion, we decided to take the metro into Red Square. Everyone describes the Moscow subway system, so I won’t, except to say that it is as clean and efficient as they write, and that it is awesome, for an American, to see the veins of a city lined with marble, gilt, and mosaic instead of filth and graffiti. It was in the subway that night that I first endured the unblinking stare of the Russian populace, a stare already described to me by Tom and by friends who had been in the Soviet Union before. “You will never not be stared at,” they told me, advising me to stare back coolly and steadily, especially at the shoes of my tormentors, since the average Soviet shoe is an embarrassment of cracked imitation leather. When we got on at the University metro stop, the scant group of passengers included two minute, humpbacked babushki; a pretty fresh-faced girl of eighteen or nineteen, who opened her mouth to yawn and revealed two aluminum teeth; a fat young mother in a minidress and platform shoes, who held a baby tightly swaddled in a ribbon-bound blanket; a group of stylish young men dressed in greasy American jeans and vinyl snap-front jackets. They all looked us up and down with undisguised fascination and whispered comments to their neighbors. Although we were dressed in what we thought was a neutral, inconspicuous fashion, the clothes we had on—cotton pants and shirts—now seemed infinitely newer, crisper, better cut than anything anyone else had on; my sandals, also, seemed to fascinate everyone. So we sat, practically riddled with stares, in the dim light of the rocking subway car, breathing an atmosphere heavy with odors of sharp tobacco, sausage, and perspiring human flesh. Tom drew a deep, happy breath. “It still smells like Russia,” he said.

We got off at the Lenin Library stop, and walked up the street to Red Square. My first view of that expanse of architectural marvels—the rolling redbrick walls of the Kremlin, with the angular mass of Lenin’s tomb directly beneath them; the Victorian birdcage that is GUM, Moscow’s largest department store; and, at the far end, St. Basil’s, the preposterous, sublime fantasy in cartoon color and buoyant plaster—made me reflect a bit enviously that whatever deficiencies there may have been in freedom and economic well-being throughout Russian and Soviet history, the people have always had compelling symbols. I have often found in myself a surprising, childish hunger for patriotic pageantry. How easy it would be, I thought, to summon up a blind surge of chauvinism if one could draw upon this vision—the sacred enclosure of Red Square, where Lenin lies preserved like a Pharaoh. Except, perhaps, for the Statue of Liberty against the steep rise of lower Manhattan, there is no emblematic scene in America with comparable drama. Facing the Kremlin, I realized for the first time how unfailingly chaste and low-key are America’s national icons; it is at once our weakness and our great strength to be bad at symbols. Our emblems seem designed for the measured response of rationality, while Russian monuments—like the Stalinist monstrosity where I am to live—evoke raw emotion.

It was a warm, humid night, and small groups of Soviet and foreign tourists were roaming the square. When we stopped to see the goose-stepping soldiers change the guard in front of Lenin’s tomb, we found that we were standing in the midst of a group of men from Soviet Uzbekistan. Brown-faced, wearing embroidered skullcaps and long quilted coats, they stared in mild amazement at this spectacle that must have seemed as alien to them as it did to us. Behind us, babushki

in black dresses and shawls were sweeping up cigarette butts from the cobblestones.

Later we walked over to have a glass of gaserevenaya vada, carbonated water flavored with fruit syrup, from one of the dispensers that apparently take the place of drinking fountains in Moscow. For two kopecks, a glass is filled with the fizzy drink; one swallows it, and then replaces the glass, to be washed by a cold spray of water for the next drinker’s use. (Hearing the amount of coughing around me even in August made me decide already that I wouldn’t make a habit of this.) We didn’t have the two kopecks for the machine, so we asked a passer-by, a tall, mournful-looking man wearing creased dark pants and a bright nylon shirt. He gave us a whole handful of change, and refused our ruble. “You’re Americans, aren’t you?” he asked us in a low voice, tugging glumly at the ends of a dandyish mustache. “Then keep the ruble. I can’t do anything with it. It’s not money. They tell me it’s money, but look in our stores and tell me what I can buy with it. Nothing!” He spat on the ground and vanished up the street.

We took the metro back to the University stop, then walked up

toward the dormitory along an avenue lined with apple trees. We passed through the tiny gatehouse in which the old woman who was supposed to check our identification was sleeping, her face a puckered mass of wrinkles, her feet resting on a rag rug where an equally ancient dog slumbered. In the courtyard was a clump of trees, and from this small grove came strains of guitar music and laughter. A girl’s voice sang snatches of “Makhno,” the poignant song from the Russian Civil War that I had heard once back in America; in her thin, tipsy soprano, however, the song sounded merry rather than sad, the voice of any student when there are still some drinks left and some time left in the evening and in the summer. Outside the grove, in the stone courtyard itself, a teenage boy and girl were chasing each other around and around, in and out of the light of the big iron lamps. They were clearly Russian, but both were dressed in jeans. When the boy neared the girl, he would try to grab her, but she dodged him each time with a shriek of laughter, her long braid streaming behind her. Their voices and footsteps echoed, faint but definite, against the walls of that monstrous folly of a building, as if they were lightheartedly defying a hostile authority. Watching them, I felt disarmed and curiously moved; I realized as well that nothing this year would be predictable or easy to fathom. In a few minutes we were climbing the steps to our own small space, and our first night in the tower.

Arrival

AUGUST 3

The tower in which we will live for most of the next ten months is one of the landmarks of Moscow, an absurd thirty-two-story wedding cake of gray and red granite, set above the city in the Lenin Hills. This titanic building, the main dormitory of Moscow State University, is a monument of the pompous and energetic style of architecture nicknamed “Stalin Gothic.” Seen from a distance, it suggests a Disney version of a ziggurat; its central spire, like the Kremlin towers, holds a blinking red star. Inside, as in a medieval fortress, there is everything necessary to sustain life in case of siege: bakeries, a dairy store, a fruit and vegetable store, a pharmacy, a post office, magazine kiosks, a watch-repair stand—all this in addition to classrooms, and student rooms, and cafeterias. On the outside, it bristles with a daft excess of decoration that is a strange twentieth-century mixture of Babylonian, Corinthian, and Slavic: there are outsized bronze flags and statues, faïence curlicues, wrought-iron sconces—even a vast reflecting pool decorated with metal water lilies the size of small cabbages. As I climb the endless stairs and negotiate the labyrinth of fusty-smelling hallways, I feel dwarfed and apprehensive, a human being lost in a palace scaled for giants.

I came to this odd new home with my husband on a summer evening two days ago, when exhaustion from long-distance travel gave every new sight the mysterious simplicity and resonance of a dream. I had my first glimpse of the Soviet Union as we broke through a cloud barrier near Sheremetyevo Airport, and found ourselves flying low over a forest of birch and evergreen, dotted with countless small ponds. There was an almost magical lushness and secrecy about this flattish northern landscape that I found powerfully attractive; suddenly I remembered that my earliest visions of Russia were of an infinite forest, dark as any forest that stretches through a child’s imagination, and peopled by swan maidens, hunter princes, fabulous bears, and witches who lived in huts set on chicken legs. Tied to Russia by no claims of blood or tradition, I still felt, while very young, an obscure attraction to this country that I knew only from its violent, highly colored folklore; its music, through which ran a similar vein of extravagance; and the dark political comments of adults. It seemed to me to be a mysterious counterweight to the known world of America—a country, like the land at the back of the north wind, in which life ran backward and the fantastic was commonplace.

Our disembarkment and passage through customs at Sheremetyevo were standard chaos, involving a long, dazed wait in a crowded room traversed from time to time by hot breezes smelling sweetly of cut grass. Only one memory remains with me from those hours: the sight of a Pioneer* excursion group of twenty small girls who seemed, by their Asiatic faces and straight black hair, to be Siberian. They all wore the blue shorts, white shirts, and red neckerchiefs that I had seen in pictures, as well as ornately curled hair bows that gave them a queer geisha look, and as I studied them with the dreamy precision of fatigue, all twenty stared back at me with an avid, unadorned curiosity. Standing beyond the customs barrier was a young man who introduced himself in English as Grigorii, a journalism student sent to meet us by the university’s office of foreign affairs. Grigorii was a dark-haired young man in his twenties, with very small eyes behind enormous round glasses and a pinched, rather gnomish body in a large, baggy suit; the impression he gave was that he had melted down slightly inside his clothing. He led us outside to a black Volga, a Soviet car that looks like a cross between a Rambler and a Plymouth. A short-legged driver, wearing a checked cap pulled down very far over his ears, stowed our bags, and soon we were speeding down a road with the vaguely horrifying sense of freedom one feels only when going through absolutely strange territory in a strange car. It was dark by now, and the smell of fields and forest rushed in through the windows. Grigorii had discovered that we both spoke Russian, and had grown garrulous. “So you are a student of Russian history?” he was saying to Tom. “I myself am extremely interested in American history—especially in your Civil War. Two years ago I even wrote a paper on the Great Barbecue.”

“The what?” asked Tom.

“The Great Barbecue—the turning point of the Reconstruction period. Don’t tell me you haven’t heard of it!” (Grigorii pronounced the word “barbecue” with the gleeful relish of a Frenchman saying “Marlboro.”)

“I haven’t,” said Tom, and as the car slid through the darkness, Grigorii illuminated for us this lost part of American history, mentioning feudal remnants, the industrial bourgeoisie, and the struggle of the working class. Listening to his small, dry, pedantic voice mention names and places I’d never heard of, I wondered what Marxist looking-glass we’d stepped through. Where on earth were we? Was he talking about the same America we had just left?

When the monstrous silhouette of the university tower appeared on the skyline, Grigorii paused to point it out proudly. “Impressive, isn’t it?” he said. “It’s the most luxurious dormitory in the Soviet Union—every year hundreds of tourists come to visit it. It’s a city block in circumference; some other time I will give you the figures on its height and number of windows. I’m sorry that we won’t be passing the reflecting pool tonight, but there is a very handsome giant barometer that I will show you. I feel very lucky to live there. We’ll be neighbors, so to speak!”

“Hurrah!” I whispered to Tom, and he dug his elbow into my ribs. Then we sat silently as the black tower grew larger against the sky.

Our arrival meant passing through a gatehouse, climbing a great many stairs, crossing a chilly marble hall, and threading through a maze of corridors on a path that led at last to a long ride in an elevator, and some kind of fuss with an old woman over a key. Although it was only about nine o’clock in the evening, a charmed stillness seemed to reign in the dormitory; we saw very few students. Instead, there seemed to be inordinate numbers of babushki—old women—in semi-official posts, knitting and nodding in dark corners like watchful beldames out of a Grimms tale. The babushka of the keys, a tiny creature with a fierce squint under a cowled white shawl, watched us struggle with the door to our room and then turned to whisper portentously to a still smaller companion, Ischo Amerikantsy—More Americans.

When Grigorii left us, we flicked a switch, and in the sudden bright light, faced our living quarters for the year. They were what Russians call a blok—a minute suite consisting of two rooms about six feet by ten feet each, a tiny entryway, and a pair of cubicles containing, between them, a toilet, a shower and washstand, and several large, indolent cockroaches. The two main rooms were painted the dispiriting beige and green of institutional rooms around the world, and furnished, rather nicely, with varnished chairs, tables, bookcases, and two single beds. (I’ve since discovered that our rooms represent great luxury, since Russian students in the same building often live four and six to such quarters.) Each room held a radio that tuned in to only one station—Radio Moscow—and at this particular moment, news was being broadcast by a woman with an excited, throaty voice. “Today,” she said, “the Party Government delegation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, led by Comrades Le Duan and Pham Van Dong visited the Kirovsky factory in Leningrad . . . In front of the monument to V. I. Lenin in Factory Square, there took place a meeting of Soviet-Vietnamese friendship . . . The Leningraders arrived at the meeting with flowers, red flags, and signs in honor of the unbreakable friendship . . . The people gathering together greeted the emissaries of the heroic Vietnamese people with warm applause . . .”

The news went off, and on came a medley of Komsomol songs delivered stalwartly by what sounded like an entire nation of ruddy-cheeked young patriots. “You can’t turn this thing off,” said Tom, fiddling with the radio knob. Indeed, like one of Orwell’s telescreens, our official radios could be turned down to inaudible, but never turned off. I began to giggle hysterically, and to calm myself, walked over to the window, from which I could see, illuminated by a spotlight on one of the pediments of the building, a gigantic bronze flag.

A bit later, in one of the fits of witless energy that sometimes replace exhaustion, we decided to take the metro into Red Square. Everyone describes the Moscow subway system, so I won’t, except to say that it is as clean and efficient as they write, and that it is awesome, for an American, to see the veins of a city lined with marble, gilt, and mosaic instead of filth and graffiti. It was in the subway that night that I first endured the unblinking stare of the Russian populace, a stare already described to me by Tom and by friends who had been in the Soviet Union before. “You will never not be stared at,” they told me, advising me to stare back coolly and steadily, especially at the shoes of my tormentors, since the average Soviet shoe is an embarrassment of cracked imitation leather. When we got on at the University metro stop, the scant group of passengers included two minute, humpbacked babushki; a pretty fresh-faced girl of eighteen or nineteen, who opened her mouth to yawn and revealed two aluminum teeth; a fat young mother in a minidress and platform shoes, who held a baby tightly swaddled in a ribbon-bound blanket; a group of stylish young men dressed in greasy American jeans and vinyl snap-front jackets. They all looked us up and down with undisguised fascination and whispered comments to their neighbors. Although we were dressed in what we thought was a neutral, inconspicuous fashion, the clothes we had on—cotton pants and shirts—now seemed infinitely newer, crisper, better cut than anything anyone else had on; my sandals, also, seemed to fascinate everyone. So we sat, practically riddled with stares, in the dim light of the rocking subway car, breathing an atmosphere heavy with odors of sharp tobacco, sausage, and perspiring human flesh. Tom drew a deep, happy breath. “It still smells like Russia,” he said.

We got off at the Lenin Library stop, and walked up the street to Red Square. My first view of that expanse of architectural marvels—the rolling redbrick walls of the Kremlin, with the angular mass of Lenin’s tomb directly beneath them; the Victorian birdcage that is GUM, Moscow’s largest department store; and, at the far end, St. Basil’s, the preposterous, sublime fantasy in cartoon color and buoyant plaster—made me reflect a bit enviously that whatever deficiencies there may have been in freedom and economic well-being throughout Russian and Soviet history, the people have always had compelling symbols. I have often found in myself a surprising, childish hunger for patriotic pageantry. How easy it would be, I thought, to summon up a blind surge of chauvinism if one could draw upon this vision—the sacred enclosure of Red Square, where Lenin lies preserved like a Pharaoh. Except, perhaps, for the Statue of Liberty against the steep rise of lower Manhattan, there is no emblematic scene in America with comparable drama. Facing the Kremlin, I realized for the first time how unfailingly chaste and low-key are America’s national icons; it is at once our weakness and our great strength to be bad at symbols. Our emblems seem designed for the measured response of rationality, while Russian monuments—like the Stalinist monstrosity where I am to live—evoke raw emotion.

It was a warm, humid night, and small groups of Soviet and foreign tourists were roaming the square. When we stopped to see the goose-stepping soldiers change the guard in front of Lenin’s tomb, we found that we were standing in the midst of a group of men from Soviet Uzbekistan. Brown-faced, wearing embroidered skullcaps and long quilted coats, they stared in mild amazement at this spectacle that must have seemed as alien to them as it did to us. Behind us, babushki

in black dresses and shawls were sweeping up cigarette butts from the cobblestones.

Later we walked over to have a glass of gaserevenaya vada, carbonated water flavored with fruit syrup, from one of the dispensers that apparently take the place of drinking fountains in Moscow. For two kopecks, a glass is filled with the fizzy drink; one swallows it, and then replaces the glass, to be washed by a cold spray of water for the next drinker’s use. (Hearing the amount of coughing around me even in August made me decide already that I wouldn’t make a habit of this.) We didn’t have the two kopecks for the machine, so we asked a passer-by, a tall, mournful-looking man wearing creased dark pants and a bright nylon shirt. He gave us a whole handful of change, and refused our ruble. “You’re Americans, aren’t you?” he asked us in a low voice, tugging glumly at the ends of a dandyish mustache. “Then keep the ruble. I can’t do anything with it. It’s not money. They tell me it’s money, but look in our stores and tell me what I can buy with it. Nothing!” He spat on the ground and vanished up the street.

We took the metro back to the University stop, then walked up

toward the dormitory along an avenue lined with apple trees. We passed through the tiny gatehouse in which the old woman who was supposed to check our identification was sleeping, her face a puckered mass of wrinkles, her feet resting on a rag rug where an equally ancient dog slumbered. In the courtyard was a clump of trees, and from this small grove came strains of guitar music and laughter. A girl’s voice sang snatches of “Makhno,” the poignant song from the Russian Civil War that I had heard once back in America; in her thin, tipsy soprano, however, the song sounded merry rather than sad, the voice of any student when there are still some drinks left and some time left in the evening and in the summer. Outside the grove, in the stone courtyard itself, a teenage boy and girl were chasing each other around and around, in and out of the light of the big iron lamps. They were clearly Russian, but both were dressed in jeans. When the boy neared the girl, he would try to grab her, but she dodged him each time with a shriek of laughter, her long braid streaming behind her. Their voices and footsteps echoed, faint but definite, against the walls of that monstrous folly of a building, as if they were lightheartedly defying a hostile authority. Watching them, I felt disarmed and curiously moved; I realized as well that nothing this year would be predictable or easy to fathom. In a few minutes we were climbing the steps to our own small space, and our first night in the tower.

Notă biografică

Andrea Lee was born in Philadelphia and received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Harvard University. She is a former staff writer forThe New Yorker, and her fiction and nonfiction writing has also appeared inThe New York Times MagazineandThe New York Times Book Review. She is the author ofRussian Journal, the novel Sarah Phillips, and the short story collectionInteresting Women. She lives with her husband and two children in Turin, Italy.