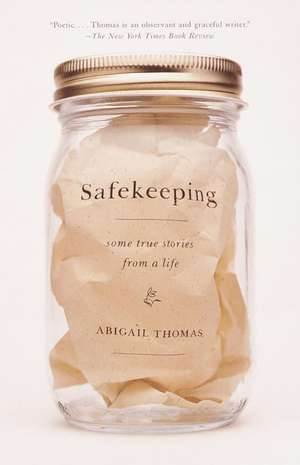

Safekeeping: Some True Stories from a Life

Autor Abigail Thomasen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2001

This is a book in which silence speaks as eloquently as what is revealed. Openhearted and effortlessly funny, these brilliantly selected glimpses of the arc of a life are, in an age of excessive confession and recrimination, a welcome tonic.

Preț: 85.16 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 128

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.29€ • 17.01$ • 13.46£

16.29€ • 17.01$ • 13.46£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385720557

ISBN-10: 0385720556

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 139 x 200 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385720556

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 139 x 200 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Abigail Thomas is the author of the novel An Actual Life and the story collections Getting Over Tom and Herb's Pajamas. She lives with her husband in New York City, where she teaches in the M.F.A. writing program at the New School.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Apple Cake

I am not a girl. I am the grandmother of six. I bake cakes for all my grandchildren. My name is synonymous with "cake." I have taught them this. Nana, Cake, and they clap their little hands. Apple cake, this is my specialty. In the past twelve days I have baked seven apple cakes for seven separate occasions. These cakes contain walnuts and raisins as well as golden oil and apples. You would beg me for a slice if you could see these cakes. You would beg for their perfume alone. They do well for holidays. Thanksgiving, for example. Anniversaries. I have had my good times and my bad. This was long ago, my dears, before most of you were born. I was not a prudish girl. Nor was I wise. When I was young I gave myself away; it was all I had to offer. But not today. Today I will bake a cake. The cake is not a metaphor. Say the words "apple cake." Apple cake. See how the mouth fills with desire.

Not Meaning to Brag

I remember one summer I was slim enough to wear a yellow polka-dot two-piece bathing suit, and still, I could see him looking sadly down the beach like a dog on a rope. No matter what, there was still only one of me. Which later he regretted taking so long to find out.

I Ate There Once

She never thought he'd get old this way. Never thought his defenses would come down one by one, dismantled, she realizes, by children. She imagines a split-rail fence coming apart over the years. He wasn't wise, she understands now, he was depressed. They both had mistaken depression for wisdom. She has married again, the third time, and she sits up front with her new husband, the nicest man in the world. Her old husband sits in back, bundled in blankets, blowing his nose in his old red kerchief, wearing his brown hat. He has gotten so gentle. Especially since she has remarried. He treats her like a flower. They have their own language. It isn't secret, but it is their own. Certain sights carry weight for them. They remember everything. She once told him she remembered the exact moment when she knew it wouldn't last. That they weren't going to stay together, that their little vessel had not been made very well, that it had sprung too many leaks, and then in anger both of them had gouged holes in the bottom. Sink, damn you, they thought. "I know when I knew it, but I didn't say anything. We were standing under that tree," she said. "I forget the name."

"It was a mimosa," he said. "The mimosa tree on the corner."

Today they are driving upstate to see their daughter graduate. Her new husband is driving. She loves his kind profile, the way he keeps asking her former husband if he is warm enough. It was he who remembered the extra lap rug. They are like three old friends, companionable, everybody on their best behavior. They pass a sign for a Mexican restaurant, coming up on the right. It is the only place to eat on the parkway. "I've always wondered what kind of place that is," says her new husband, slowing down for a look as they approach. "Unlikely spot for a restaurant. The food must be terrible." The restaurant, only barely visible through trees, vanishes behind them. As it happens, it was here that she and her second husband had eaten their wedding supper, twenty-five years ago. They were by themselves and had been married about an hour.

"I ate there once," she says. Her expression doesn't change. She doesn't turn around.

"So did I," says a voice from the back.

The Animal They Made

Once they were no longer married he was free to love her again and she was free to love him too so after a while they did. Because they had always loved each other, and because of the animal they made. Not a real animal, nothing born in a litter, nothing fashioned out of clay or wood or brass, and not the beast with two backs, but what they were, the two of them together. The animal they made, that's the only way she can describe it. An animal with its own life, its own life history, its own life span. Its own intelligence. Its own memories and regrets. Its own sins. An animal with its eyes and ears open, so alive, so alive. Greeting them! Making jokes out of thin air. Extinct now.

Power

She was sixteen and wearing a tight yellow sweater. It had shrunk, but she had to go to school and nothing else was clean. Her route was along Washington Mews, up University to Fourteenth Street, along Fourteenth to Third Avenue, then up Third to Fifteenth, then one more block east to school. It was a warm fall day. I believe she was also wearing a short plaid skirt, A-line, and probably loafers and no socks. She never could find socks. The men in New York City, where she had just moved, stared. Some of them put down their tools or else just held them slackly as she walked by. They murmured. My god, she realized. I have power. Like most power it was both utterly real and utterly illusory. But she spent the next forty years with her eye on who was looking back. This didn't get in her way. It was her way. Her ambition was to be desired. Now it's over and what a relief. Finally she can get some work done.

Nothing Is Wasted

She is a writer and she teaches writing. Well, not teaches writing because you can't do that, but you can certainly locate the interesting, you can go over the page with sand-papered fingertips and say, Here, what is really going on here, and if you're lucky the writer blushes and says, Oh I thought I could just skip over that part, which means you have discovered a gold mine, and you say, No, sorry, you're going to have to write it. You can point out the promising. You can encourage and allow and permit and make possible. She gives assignments so nobody has to face the blank page alone with the whole blue sky to choose from. After all she knows how hard it is to make it up from whole cloth; everybody needs a shred of something to start with to cover their nakedness and so to this end she wanders around the city with her eyes and ears open. On the subway one afternoon she sees a man holding what appears to be a silver Buddha. Good lord, she wonders, what is he doing with that? Is he going to sell it? Is she going to buy it? Where did a silver Buddha come from? Then as she is watching he brings it toward his mouth and bites off the head. How completely baffling until she sees it is not a Buddha but something edible, some sort of wafer wrapped in silver paper. Perhaps chocolate. Nevertheless, she tells her class that night, Write two pages in which somebody is eating something unusual on the bus. Write two pages, she says, in which somebody can't stop apologizing. Two pages in which somebody kills something with a shoe. Two pages containing a French horn, an ear infection, and a limp. Describe somebody by what they can't take their eyes off. Two pages. Two pages in which someone is inappropriately dressed for the occasion. And so forth. Nothing goes to waste.

Passion

Even though she's a grandmother now she loves to watch people kiss. She loves how their arms go around each other, how their eyes close, how their lips meet. She loves watching them make out at bus stops, entrances to subway stations. Sometimes one of them is crying and she feels sad and very interested and she makes up reasons why, one or another is going away, maybe, back to Ohio or into the army. Or they are breaking up. But she likes it best when they aren't crying. Take today on the subway, for instance. She sat with a grandson on either side of her and right across was a couple eating candy out of two paper bags, feeding each other those soft pieces of yellow peanut-shaped candies and unable to keep their hands off each other. They were skinny and pale, their faces ravaged and sick, she was pretty sure they were junkies, but every time the boy leaned over to kiss the girl, the cords stood out in his neck. Oh, she thought, trembling. Such passion. Meanwhile the boys were reading a poem by a Chinese poet of the ninth century among the ads for jeans and liquor on the subway car. She smiled to herself and squeezed their warm hands because love comes and goes in so many forms and in this city passion is everywhere you look and all you have to do is breathe it in.

What I Know

It doesn't take much--the glimpse of a bare-legged girl crouching on the second-story porch of a house with five mailboxes, and I know without looking any harder that she is feeding a baby. I can see through the slats of the railing, and it is all in the curve of her back, the position of her shoulder and arm, the posture of intent. I know she is feeding a baby and the baby sits in a small plastic chair on the floor of the porch. Maybe now and then she takes a spoonful herself, if it's cereal with peaches or plum tapioca dessert in that little jar. Somewhere there are tiny shirts and crib sheets drying in the sun, and indoors a cat stretches on a beat-up chair. There is probably a sink full of dishes. Maybe she is thinking of the life she won't have now, although she loves this tiny human creature she has made out of herself. I know for years she will listen to the radio and think of boys she might have had a different future with. What is this longing, she will want to ask. This troubling feeling of more to come. You can make something out of it, I want to tell her. But that's what her life is for.

From the Hardcover edition.

I am not a girl. I am the grandmother of six. I bake cakes for all my grandchildren. My name is synonymous with "cake." I have taught them this. Nana, Cake, and they clap their little hands. Apple cake, this is my specialty. In the past twelve days I have baked seven apple cakes for seven separate occasions. These cakes contain walnuts and raisins as well as golden oil and apples. You would beg me for a slice if you could see these cakes. You would beg for their perfume alone. They do well for holidays. Thanksgiving, for example. Anniversaries. I have had my good times and my bad. This was long ago, my dears, before most of you were born. I was not a prudish girl. Nor was I wise. When I was young I gave myself away; it was all I had to offer. But not today. Today I will bake a cake. The cake is not a metaphor. Say the words "apple cake." Apple cake. See how the mouth fills with desire.

Not Meaning to Brag

I remember one summer I was slim enough to wear a yellow polka-dot two-piece bathing suit, and still, I could see him looking sadly down the beach like a dog on a rope. No matter what, there was still only one of me. Which later he regretted taking so long to find out.

I Ate There Once

She never thought he'd get old this way. Never thought his defenses would come down one by one, dismantled, she realizes, by children. She imagines a split-rail fence coming apart over the years. He wasn't wise, she understands now, he was depressed. They both had mistaken depression for wisdom. She has married again, the third time, and she sits up front with her new husband, the nicest man in the world. Her old husband sits in back, bundled in blankets, blowing his nose in his old red kerchief, wearing his brown hat. He has gotten so gentle. Especially since she has remarried. He treats her like a flower. They have their own language. It isn't secret, but it is their own. Certain sights carry weight for them. They remember everything. She once told him she remembered the exact moment when she knew it wouldn't last. That they weren't going to stay together, that their little vessel had not been made very well, that it had sprung too many leaks, and then in anger both of them had gouged holes in the bottom. Sink, damn you, they thought. "I know when I knew it, but I didn't say anything. We were standing under that tree," she said. "I forget the name."

"It was a mimosa," he said. "The mimosa tree on the corner."

Today they are driving upstate to see their daughter graduate. Her new husband is driving. She loves his kind profile, the way he keeps asking her former husband if he is warm enough. It was he who remembered the extra lap rug. They are like three old friends, companionable, everybody on their best behavior. They pass a sign for a Mexican restaurant, coming up on the right. It is the only place to eat on the parkway. "I've always wondered what kind of place that is," says her new husband, slowing down for a look as they approach. "Unlikely spot for a restaurant. The food must be terrible." The restaurant, only barely visible through trees, vanishes behind them. As it happens, it was here that she and her second husband had eaten their wedding supper, twenty-five years ago. They were by themselves and had been married about an hour.

"I ate there once," she says. Her expression doesn't change. She doesn't turn around.

"So did I," says a voice from the back.

The Animal They Made

Once they were no longer married he was free to love her again and she was free to love him too so after a while they did. Because they had always loved each other, and because of the animal they made. Not a real animal, nothing born in a litter, nothing fashioned out of clay or wood or brass, and not the beast with two backs, but what they were, the two of them together. The animal they made, that's the only way she can describe it. An animal with its own life, its own life history, its own life span. Its own intelligence. Its own memories and regrets. Its own sins. An animal with its eyes and ears open, so alive, so alive. Greeting them! Making jokes out of thin air. Extinct now.

Power

She was sixteen and wearing a tight yellow sweater. It had shrunk, but she had to go to school and nothing else was clean. Her route was along Washington Mews, up University to Fourteenth Street, along Fourteenth to Third Avenue, then up Third to Fifteenth, then one more block east to school. It was a warm fall day. I believe she was also wearing a short plaid skirt, A-line, and probably loafers and no socks. She never could find socks. The men in New York City, where she had just moved, stared. Some of them put down their tools or else just held them slackly as she walked by. They murmured. My god, she realized. I have power. Like most power it was both utterly real and utterly illusory. But she spent the next forty years with her eye on who was looking back. This didn't get in her way. It was her way. Her ambition was to be desired. Now it's over and what a relief. Finally she can get some work done.

Nothing Is Wasted

She is a writer and she teaches writing. Well, not teaches writing because you can't do that, but you can certainly locate the interesting, you can go over the page with sand-papered fingertips and say, Here, what is really going on here, and if you're lucky the writer blushes and says, Oh I thought I could just skip over that part, which means you have discovered a gold mine, and you say, No, sorry, you're going to have to write it. You can point out the promising. You can encourage and allow and permit and make possible. She gives assignments so nobody has to face the blank page alone with the whole blue sky to choose from. After all she knows how hard it is to make it up from whole cloth; everybody needs a shred of something to start with to cover their nakedness and so to this end she wanders around the city with her eyes and ears open. On the subway one afternoon she sees a man holding what appears to be a silver Buddha. Good lord, she wonders, what is he doing with that? Is he going to sell it? Is she going to buy it? Where did a silver Buddha come from? Then as she is watching he brings it toward his mouth and bites off the head. How completely baffling until she sees it is not a Buddha but something edible, some sort of wafer wrapped in silver paper. Perhaps chocolate. Nevertheless, she tells her class that night, Write two pages in which somebody is eating something unusual on the bus. Write two pages, she says, in which somebody can't stop apologizing. Two pages in which somebody kills something with a shoe. Two pages containing a French horn, an ear infection, and a limp. Describe somebody by what they can't take their eyes off. Two pages. Two pages in which someone is inappropriately dressed for the occasion. And so forth. Nothing goes to waste.

Passion

Even though she's a grandmother now she loves to watch people kiss. She loves how their arms go around each other, how their eyes close, how their lips meet. She loves watching them make out at bus stops, entrances to subway stations. Sometimes one of them is crying and she feels sad and very interested and she makes up reasons why, one or another is going away, maybe, back to Ohio or into the army. Or they are breaking up. But she likes it best when they aren't crying. Take today on the subway, for instance. She sat with a grandson on either side of her and right across was a couple eating candy out of two paper bags, feeding each other those soft pieces of yellow peanut-shaped candies and unable to keep their hands off each other. They were skinny and pale, their faces ravaged and sick, she was pretty sure they were junkies, but every time the boy leaned over to kiss the girl, the cords stood out in his neck. Oh, she thought, trembling. Such passion. Meanwhile the boys were reading a poem by a Chinese poet of the ninth century among the ads for jeans and liquor on the subway car. She smiled to herself and squeezed their warm hands because love comes and goes in so many forms and in this city passion is everywhere you look and all you have to do is breathe it in.

What I Know

It doesn't take much--the glimpse of a bare-legged girl crouching on the second-story porch of a house with five mailboxes, and I know without looking any harder that she is feeding a baby. I can see through the slats of the railing, and it is all in the curve of her back, the position of her shoulder and arm, the posture of intent. I know she is feeding a baby and the baby sits in a small plastic chair on the floor of the porch. Maybe now and then she takes a spoonful herself, if it's cereal with peaches or plum tapioca dessert in that little jar. Somewhere there are tiny shirts and crib sheets drying in the sun, and indoors a cat stretches on a beat-up chair. There is probably a sink full of dishes. Maybe she is thinking of the life she won't have now, although she loves this tiny human creature she has made out of herself. I know for years she will listen to the radio and think of boys she might have had a different future with. What is this longing, she will want to ask. This troubling feeling of more to come. You can make something out of it, I want to tell her. But that's what her life is for.

From the Hardcover edition.

Textul de pe ultima copertă

A beautifully crafted and inviting account of one woman's life, Safekeeping offers a sublimely different kind of autobiography. Setting aside a straightforward narrative in favor of brief passages of vivid prose, Thomas revisits the pivotal moments and tiny incidents that have shaped her: pregnancy at 18, single motherhood of three by the age of 26, the joys and frustrations of her marriages, and the death of her second husband. With startling clarity and unwavering composure, Thomas tells stories made of mistakes and loyalties, adventures and domesticities, of experiences both deeply personal and universal.

This is a book in which silence speaks as eloquently as what is revealed. Openhearted and effortlessly funny, these brilliantly selected glimpses of the arc of life are, in an age of too much confession, a welcome tonic.