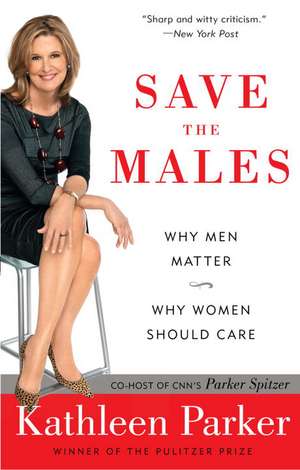

Save the Males: Why Men Matter Why Women Should Care

Autor Kathleen Parkeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2010

Preț: 115.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.07€ • 22.96$ • 18.22£

22.07€ • 22.96$ • 18.22£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812976953

ISBN-10: 0812976959

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812976959

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Kathleen Parker is a nationally syndicated columnist whose twice-weekly column runs in more than four hundred newspapers around the country. An H. L. Mencken Writing Award winner, she frequently appears on radio talk shows and is a regular guest on The Chris Matthews Show.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

women good, men bad

Males have become the portmanteau cause of evil behavior, and it’s acceptable to downgrade males.

—Lionel Tiger, Charles Darwin Professor of Anthropology, Rutgers University

Jackson Marlette was just fourteen when he summed up the anti-male zeitgeist for his father, political cartoonist and author Doug Marlette. They were in a North Carolina chicken joint awaiting their orders when the younger Marlette picked up a table-top ad boasting boneless chicken and read aloud: “Chicken good, bones bad.”

Then, beaming with insight, Jackson made the analogous leap and proclaimed: “Women good, men bad!”

Yesssssss! Give that boy a lifetime pass to The Vagina Monologues.

Fourteen years isn’t long to roam the earth, but boys learn early that they belong to the “bad” sex and their female counterparts to the “good.” For many, their indoctrination starts the moment they begin school and observe that teachers (who are, for the most part, females) prefer less rambunctious girl behavior. Boys’ programming continues through high school and then into college, where male students are often treated to an orientation primer in sexual harassment and date rape. A friend’s son attended one such seminar on his first day at Harvard. “It scared the s—— out of him,” his father reported. “He said, ‘Dad, I’m never going on a date.’”

Smart lad.

America is a dangerous place for males these days. Look at a girl the wrong way—or the right way, if you’re a gal of a certain age (why do you think all those fifty-year-old women are flocking to Italy?)—and you’ll get slapped. With an open palm if you’re lucky; with a lawsuit if you’re not. Or worse, a visit to Human Resources for reprogramming. Misinterpret her body language and you might wind up in prison.

The first hint for Jackson and other boys of the now twentysomething generation that life wasn’t going to be precisely fair was when, beginning in 1993, they were told that girls would be getting out of school for “Take Our Daughters to Work Day,” a creation of the Ms. Foundation for Women and possibly the daffiest idea ever dreamed up in the powder room. This is ancient history now, but not irrelevant to sexual relations today. The familiar premise was that girls needed to visit the working world in order to visualize themselves in nontraditional roles. If they saw women only in the home, where more-traditional mothers presumably spent their days watching soaps and seducing the gardener, how could they grow up to be firemen, jet pilots, and Harvard scientists?

But there was more to the Ms. mission than role modeling. The subtext was that little girls would absorb the rage of their feminist foremothers and become militant grrrrrrls who could, by goddess, kick boy butt—anytime, anywhere. Marie C. Wilson, a former Ms. Foundation president, put it this way: “When girls came into offices, factories, and firehouses, we knew they would see opportunities for their future, but we also anticipated that girls would perceive inequities in the workplace and ask the hard questions that have no easy answers—like why most of the bosses were men and can you have a family and work here, too?”

Such feminist fantasies probably were not the burning agendas of nine- and ten-year-olds—or even teenage daughters—who more likely were tilting toward “Is there a mall near here?” It was assumed, meanwhile, that boys would have no such visionary problems, given that they saw men in professional and other working roles on a daily basis. The feminist narrative, now firmly entrenched in the culture at large, was that boys could afford to stay behind and learn the lesson that would shadow them into adulthood: that they are unfairly privileged by virtue of their maleness, and they will be punished for it.

After a few years of protest from agenda-free parents who had sons as well as daughters, the girls-only day was tweaked in 2003 to include boys under the broader title of “Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day”—a nice gesture, if too late for a generation of boys who had obediently absorbed the message that males were guilty for being male and females were entitled to, oh, everything.

Or had they?

More likely, boys had absorbed the message that life isn’t fair and that girls are to blame. Girls weren’t really to blame, obviously, but kids will be kids. Nobody likes a teacher’s pet, and girls were the culture’s pets. We browbeat our kids about the importance of sharing and being nice, then one day the gender fairy flits into their lives and sprinkles cootie dust on all things male. Human nature being what it is, boys were unlikely to respond favorably to the news. Getting out of school for a day, after all, is otherwise known as playing hooky—while staying behind with a female teacher, most likely a feminist herself, to have his brain chip tuned must be a little boy’s idea of hell. I know it is mine.

That corporate America participated in the go-girl-play-hooky farce merely reflects how effective feminists had been. Men weren’t about to protest when daughters began filing in for their state-sanctioned day of privilege. Men have daughters, too, after all. They wanted to do the right thing, even if it was, in fact, the wrong thing for their sons.

If boys weren’t perfectly clear on the specialness of girls, female teachers weaned on feminist ideology were poised to fill in the gaps. One of my son’s middle school teachers studiously refused to use male pronouns, a curious tic I noticed during an orientation meeting. Every time a pronoun was required, she used she or her, never he or him, effectively erasing boys from the classroom. I sympathize with anyone wishing to avoid the awkward his/her construction. I also understand the inclination to alternate between the two—his in one sentence, her in the next—though such tortured pronoun equity becomes distracting and annoying. I even understand and often resort to the all-encompassing they and their, which gathers everyone under one gender-neutral third-person umbrella, offending no one and exalting the totality of Gender Oneness.

But Miss Andry, as we affectionately called this teacher en famille, went to the extreme of simply omitting the male sex altogether. Nothing subtle about that. He simply didn’t exist for her, while She was everything a girl-teacher could want. Miss Andry made clear her preference for girls in other ways throughout the year. One memorable day, she brought doughnuts to class just for the girls. When my then eleven-year-old son asked why he couldn’t have a doughnut, she said, “Because I don’t like boys.” Glad we got that straight. To be fair, maybe it was “Girls Day” and Miss Andry was kidding, but little boys that age can be nuance-challenged. We would find it intolerable, certainly, if a male teacher said something similar to an eleven-year-old girl.

Teachers like Miss Andry most likely are products of the pro-girl education reform movement that captured America’s imagination in the 1990s. Several books and studies emerged during that time claiming that education reinforced gender stereotypes that were damaging to girls. All those lessons about men drafting the U.S. Constitution and inventing electricity ’n’ stuff apparently harmed girls’ self-esteem. Where were the mothers of invention?

The Crisis Wars

The girl crisis got rolling in 1989, when Harvard professor Carol Gilligan claimed that her research showed girls suffered from a patriarchal educational system that favored boys and silenced girls. In her words: “As the river of a girl’s life flows into the sea of Western culture, she is in danger of drowning or disappearing.” As a former girl, I’m thinking: So speak up or swim, sister.

Feminist groups whose existence was predicated on the victimhood of women quickly embraced the girl crisis meme. No crisis, no ism, no research funds. Gilligan’s claims were followed by a report from the American Association of University Women called Shortchanging Girls, Shortchanging America that spoke of the unacknowledged American tragedy of esteem-bereft girls. Then in 1994, journalist Peggy Orenstein published Schoolgirls, about girls’ lack of confidence in school owing to the “hidden curriculum” that girls should be quiet and subordinate to boys.

Next came Mary Pipher’s 1994 bestseller, Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls, in which she described America’s “girl-destroying” culture. A clinical psychologist, Pipher claimed that girls in early adolescence take a dive, losing the confidence of girlhood and becoming mysteriously sullen and self-absorbed. We used to call this “the teenage years,” but suddenly we needed to restructure education to deal with girls who allegedly were lagging behind boys owing to the onset of puberty.

By these descriptions, one would have thought that girls were being shackled to desks (constructed to resemble kitchen stoves) and their mouths duct-taped shut. Congress came to the rescue with the Gender Equity in Education Act, and a new million-dollar industry was born to study gender bias in America’s schools. By 1995, the girl crisis was considered so severe that American delegates to the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing made girls’ low self-esteem a human rights issue.

You can’t help admiring the momentum. In just five years, the germ of an idea had become a full-blown movement. Girls had to be saved! No doubt Chinese women, who risk being shot for shouting “Democracy!” in a crowded theater, were amused to hear American women bemoaning the sad girls back home suffering self-esteem issues. Men, meanwhile, have to marvel at the efficiency of their female counterparts. The men’s movement has been in gestation for about twenty years and has yet to quicken, much less emerge to alter the gender ecosystem.

It is a wonder that women of my generation, who grew up among smart math-boys—and who somehow survived puberty without a government program—also managed to become doctors, lawyers, journalists, scholars, Supreme Court justices, presidential candidates, and, yes, even delegates to world conferences. Among those scholars is a national treasure named Christina Hoff Sommers—philosopher and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, author of The War Against Boys, and also the mother of a son. Sommers neatly debunked the girl crisis by rudely examining the hard data used in Gilligan’s research, which revealed a small sample size of girls at an elite boarding school. Not exactly your average American cross section. I’m not a social scientist, but as a parent I’d venture to guess that Gilligan’s girls might be “drowning and disappearing” because they’ve been coddled and pampered into self-absorption—always a fast track to human misery, though nothing a little yardwork won’t cure.

As most of us know, having been children ourselves, girls have problems because growing up is hard to do, and being a girl is biologically unfair. Boys have problems because being a boy is no picnic, either, though they do get to skip the monthly doldrums. What ails most children who are having “issues” is most likely tied to broken families, a confusing, sexually aggressive culture, and gender hostilities created and promoted by academic theorists with time and money to spend.

From the Hardcover edition.

women good, men bad

Males have become the portmanteau cause of evil behavior, and it’s acceptable to downgrade males.

—Lionel Tiger, Charles Darwin Professor of Anthropology, Rutgers University

Jackson Marlette was just fourteen when he summed up the anti-male zeitgeist for his father, political cartoonist and author Doug Marlette. They were in a North Carolina chicken joint awaiting their orders when the younger Marlette picked up a table-top ad boasting boneless chicken and read aloud: “Chicken good, bones bad.”

Then, beaming with insight, Jackson made the analogous leap and proclaimed: “Women good, men bad!”

Yesssssss! Give that boy a lifetime pass to The Vagina Monologues.

Fourteen years isn’t long to roam the earth, but boys learn early that they belong to the “bad” sex and their female counterparts to the “good.” For many, their indoctrination starts the moment they begin school and observe that teachers (who are, for the most part, females) prefer less rambunctious girl behavior. Boys’ programming continues through high school and then into college, where male students are often treated to an orientation primer in sexual harassment and date rape. A friend’s son attended one such seminar on his first day at Harvard. “It scared the s—— out of him,” his father reported. “He said, ‘Dad, I’m never going on a date.’”

Smart lad.

America is a dangerous place for males these days. Look at a girl the wrong way—or the right way, if you’re a gal of a certain age (why do you think all those fifty-year-old women are flocking to Italy?)—and you’ll get slapped. With an open palm if you’re lucky; with a lawsuit if you’re not. Or worse, a visit to Human Resources for reprogramming. Misinterpret her body language and you might wind up in prison.

The first hint for Jackson and other boys of the now twentysomething generation that life wasn’t going to be precisely fair was when, beginning in 1993, they were told that girls would be getting out of school for “Take Our Daughters to Work Day,” a creation of the Ms. Foundation for Women and possibly the daffiest idea ever dreamed up in the powder room. This is ancient history now, but not irrelevant to sexual relations today. The familiar premise was that girls needed to visit the working world in order to visualize themselves in nontraditional roles. If they saw women only in the home, where more-traditional mothers presumably spent their days watching soaps and seducing the gardener, how could they grow up to be firemen, jet pilots, and Harvard scientists?

But there was more to the Ms. mission than role modeling. The subtext was that little girls would absorb the rage of their feminist foremothers and become militant grrrrrrls who could, by goddess, kick boy butt—anytime, anywhere. Marie C. Wilson, a former Ms. Foundation president, put it this way: “When girls came into offices, factories, and firehouses, we knew they would see opportunities for their future, but we also anticipated that girls would perceive inequities in the workplace and ask the hard questions that have no easy answers—like why most of the bosses were men and can you have a family and work here, too?”

Such feminist fantasies probably were not the burning agendas of nine- and ten-year-olds—or even teenage daughters—who more likely were tilting toward “Is there a mall near here?” It was assumed, meanwhile, that boys would have no such visionary problems, given that they saw men in professional and other working roles on a daily basis. The feminist narrative, now firmly entrenched in the culture at large, was that boys could afford to stay behind and learn the lesson that would shadow them into adulthood: that they are unfairly privileged by virtue of their maleness, and they will be punished for it.

After a few years of protest from agenda-free parents who had sons as well as daughters, the girls-only day was tweaked in 2003 to include boys under the broader title of “Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day”—a nice gesture, if too late for a generation of boys who had obediently absorbed the message that males were guilty for being male and females were entitled to, oh, everything.

Or had they?

More likely, boys had absorbed the message that life isn’t fair and that girls are to blame. Girls weren’t really to blame, obviously, but kids will be kids. Nobody likes a teacher’s pet, and girls were the culture’s pets. We browbeat our kids about the importance of sharing and being nice, then one day the gender fairy flits into their lives and sprinkles cootie dust on all things male. Human nature being what it is, boys were unlikely to respond favorably to the news. Getting out of school for a day, after all, is otherwise known as playing hooky—while staying behind with a female teacher, most likely a feminist herself, to have his brain chip tuned must be a little boy’s idea of hell. I know it is mine.

That corporate America participated in the go-girl-play-hooky farce merely reflects how effective feminists had been. Men weren’t about to protest when daughters began filing in for their state-sanctioned day of privilege. Men have daughters, too, after all. They wanted to do the right thing, even if it was, in fact, the wrong thing for their sons.

If boys weren’t perfectly clear on the specialness of girls, female teachers weaned on feminist ideology were poised to fill in the gaps. One of my son’s middle school teachers studiously refused to use male pronouns, a curious tic I noticed during an orientation meeting. Every time a pronoun was required, she used she or her, never he or him, effectively erasing boys from the classroom. I sympathize with anyone wishing to avoid the awkward his/her construction. I also understand the inclination to alternate between the two—his in one sentence, her in the next—though such tortured pronoun equity becomes distracting and annoying. I even understand and often resort to the all-encompassing they and their, which gathers everyone under one gender-neutral third-person umbrella, offending no one and exalting the totality of Gender Oneness.

But Miss Andry, as we affectionately called this teacher en famille, went to the extreme of simply omitting the male sex altogether. Nothing subtle about that. He simply didn’t exist for her, while She was everything a girl-teacher could want. Miss Andry made clear her preference for girls in other ways throughout the year. One memorable day, she brought doughnuts to class just for the girls. When my then eleven-year-old son asked why he couldn’t have a doughnut, she said, “Because I don’t like boys.” Glad we got that straight. To be fair, maybe it was “Girls Day” and Miss Andry was kidding, but little boys that age can be nuance-challenged. We would find it intolerable, certainly, if a male teacher said something similar to an eleven-year-old girl.

Teachers like Miss Andry most likely are products of the pro-girl education reform movement that captured America’s imagination in the 1990s. Several books and studies emerged during that time claiming that education reinforced gender stereotypes that were damaging to girls. All those lessons about men drafting the U.S. Constitution and inventing electricity ’n’ stuff apparently harmed girls’ self-esteem. Where were the mothers of invention?

The Crisis Wars

The girl crisis got rolling in 1989, when Harvard professor Carol Gilligan claimed that her research showed girls suffered from a patriarchal educational system that favored boys and silenced girls. In her words: “As the river of a girl’s life flows into the sea of Western culture, she is in danger of drowning or disappearing.” As a former girl, I’m thinking: So speak up or swim, sister.

Feminist groups whose existence was predicated on the victimhood of women quickly embraced the girl crisis meme. No crisis, no ism, no research funds. Gilligan’s claims were followed by a report from the American Association of University Women called Shortchanging Girls, Shortchanging America that spoke of the unacknowledged American tragedy of esteem-bereft girls. Then in 1994, journalist Peggy Orenstein published Schoolgirls, about girls’ lack of confidence in school owing to the “hidden curriculum” that girls should be quiet and subordinate to boys.

Next came Mary Pipher’s 1994 bestseller, Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls, in which she described America’s “girl-destroying” culture. A clinical psychologist, Pipher claimed that girls in early adolescence take a dive, losing the confidence of girlhood and becoming mysteriously sullen and self-absorbed. We used to call this “the teenage years,” but suddenly we needed to restructure education to deal with girls who allegedly were lagging behind boys owing to the onset of puberty.

By these descriptions, one would have thought that girls were being shackled to desks (constructed to resemble kitchen stoves) and their mouths duct-taped shut. Congress came to the rescue with the Gender Equity in Education Act, and a new million-dollar industry was born to study gender bias in America’s schools. By 1995, the girl crisis was considered so severe that American delegates to the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing made girls’ low self-esteem a human rights issue.

You can’t help admiring the momentum. In just five years, the germ of an idea had become a full-blown movement. Girls had to be saved! No doubt Chinese women, who risk being shot for shouting “Democracy!” in a crowded theater, were amused to hear American women bemoaning the sad girls back home suffering self-esteem issues. Men, meanwhile, have to marvel at the efficiency of their female counterparts. The men’s movement has been in gestation for about twenty years and has yet to quicken, much less emerge to alter the gender ecosystem.

It is a wonder that women of my generation, who grew up among smart math-boys—and who somehow survived puberty without a government program—also managed to become doctors, lawyers, journalists, scholars, Supreme Court justices, presidential candidates, and, yes, even delegates to world conferences. Among those scholars is a national treasure named Christina Hoff Sommers—philosopher and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, author of The War Against Boys, and also the mother of a son. Sommers neatly debunked the girl crisis by rudely examining the hard data used in Gilligan’s research, which revealed a small sample size of girls at an elite boarding school. Not exactly your average American cross section. I’m not a social scientist, but as a parent I’d venture to guess that Gilligan’s girls might be “drowning and disappearing” because they’ve been coddled and pampered into self-absorption—always a fast track to human misery, though nothing a little yardwork won’t cure.

As most of us know, having been children ourselves, girls have problems because growing up is hard to do, and being a girl is biologically unfair. Boys have problems because being a boy is no picnic, either, though they do get to skip the monthly doldrums. What ails most children who are having “issues” is most likely tied to broken families, a confusing, sexually aggressive culture, and gender hostilities created and promoted by academic theorists with time and money to spend.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Sharp and witty criticism.”—New York Post

“Save the Males is witty and it’s going to make you laugh, but it is also serious, thoughtful, brilliantly observed, and dead-on.”—Peggy Noonan

“Kathleen Parker proves to be not just a sharp thinker but a blithe spirit. While most social critics fight the gender wars from the female side, Parker throws our men and our boys an intelligent, heartfelt, humorous life jacket.” —Margaret Carlson

“Arresting, entertaining, and serious.”—The New York Times

“Fierce and funny.”—Toronto Star

“Save the Males is witty and it’s going to make you laugh, but it is also serious, thoughtful, brilliantly observed, and dead-on.”—Peggy Noonan

“Kathleen Parker proves to be not just a sharp thinker but a blithe spirit. While most social critics fight the gender wars from the female side, Parker throws our men and our boys an intelligent, heartfelt, humorous life jacket.” —Margaret Carlson

“Arresting, entertaining, and serious.”—The New York Times

“Fierce and funny.”—Toronto Star