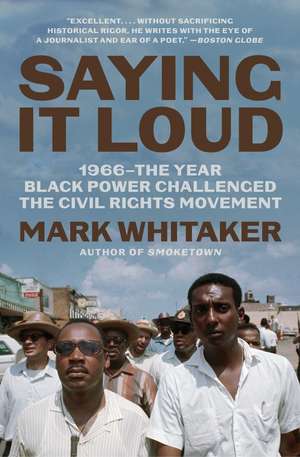

Saying It Loud: 1966—The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement

Autor Mark Whitakeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 mar 2024

In “crisp prose” (The New York Times) and novelistic detail Saying It Loud tells the story of how the Black Power phenomenon began to challenge the traditional civil rights movement in the turbulent year of 1966. Saying It Loud takes you inside the dramatic events in this seminal year, from Stokely Carmichael’s middle-of-the-night ouster of moderate icon John Lewis as a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to Carmichael’s impassioned cry of “Black Power!” during a protest march in rural Mississippi. From Julian Bond’s humiliating and racist ouster from the Georgia state legislature because of his antiwar statements to Ronald Reagan’s election as California governor riding a “white backlash” vote against Black Power and urban unrest. From the founding of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California, to the origins of Kwanzaa, the Black Arts Movement, and the first Black studies programs. From Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ill-fated campaign to take the civil rights movement north to Chicago to the wrenching ousting of the white members of SNCC.

Deeply researched and widely reported, Saying It Loud offers brilliant portraits of the major characters in the yearlong drama and provides new details and insights from key players and journalists who covered the story. It also makes a compelling case for why the lessons from 1966 still resonate in the era of Black Lives Matter and the fierce contemporary battles over voting rights, identity politics, and the teaching of Black History.

Preț: 57.56 lei

Preț vechi: 70.71 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 86

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.01€ • 11.38$ • 9.16£

11.01€ • 11.38$ • 9.16£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-12 martie

Livrare express 12-18 februarie pentru 36.24 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982114138

ISBN-10: 1982114134

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg b-w insert; 1 photo t-o;

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982114134

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg b-w insert; 1 photo t-o;

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Mark Whitaker is the former editor of Newsweek and the first African American to lead a national newsweekly. He then served as Washington Bureau Chief for NBC News and Managing Editor of CNN Worldwide. Whitaker’s memoir My Long Trip Home was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. His social histories Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance and Saying it Loud: 1966—The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement were both named among the best nonfiction books of the year by The Washington Post.

Extras

Prologue: December 31, 1965: The Road to Black PowerPROLOGUE DECEMBER 31, 1965 The Road to Black Power

In the middle of Alabama, U.S. Route 80, the highway that links Selma and Montgomery, narrows to two lanes as it passes through Lowndes County, deep in the former cotton plantation territory known as the Black Belt. For decades, the deadly reach of the Ku Klux Klan made this slender stretch of open road, surrounded by swamps and spindly trees covered with Spanish moss, one of the scariest in the South. During the historic civil rights march between those two cities in 1965, fewer than three hundred protesters braved the Lowndes County leg, whispering as they hurried through a rainstorm about rumors of bombs and snipers lurking out of sight. When the march ended, cars transporting demonstrators back to Selma drove as fast as they could through Lowndes County, without stopping.

One car didn’t make it. Viola Liuzzo was a thirty-nine-year-old mother of five from Detroit who had answered the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for whites to join the Selma march. After it was over, she was helping drive marchers back from Montgomery along with a young Black volunteer named Leroy Moton. As the two headed back to Montgomery after a drop-off in Selma shortly after nightfall, a red-and-white Chevrolet Impala pulled alongside Liuzzo’s blue Oldsmobile on Route 80. A spray of bullets exploded into the driver’s side window, and the car careened off the road and into a ditch. Moton passed out, and when he came to Liuzzo was slumped lifeless on the bench front seat, her foot still on the accelerator. Moton raced through the darkness to report the attack—which, it would soon emerge, was carried out by four Alabama Klansmen, one of them a paid informant for the FBI.

Two days later, as newspapers across the country ran front-page updates on the murder of the first white woman to die in the civil rights struggle, five young Black organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee slipped unnoticed into Lowndes County on Route 80. The five were there to bring SNCC’s mission of voter registration to the county, an impoverished backwater with the largest percentage of Black residents in the state, but where not a single Black had cast a ballot in more than sixty years. The group’s leader was Stokely Carmichael, a lanky New Yorker with a long, angular nose and heavy-lidded but expressive eyes. His voice mixed the lilt of Trinidad, where he lived until age eleven; the urgency of the Bronx, where he spent his teens; and the polish of Howard University, the distinguished historically Black college from which Carmichael graduated. Over the next eight months, SNCC organizers proved successful enough that white farmers punished Black sharecroppers who registered to vote by evicting them from their land. So it was that, as the year 1965 ended, Carmichael and his comrades found themselves back along Route 80, erecting tents for displaced families while sharecroppers armed with hunting rifles kept watch for night-riding Klansmen.

On the second to last day of December, Carmichael was putting up tents on a six-acre plot that a local church group had purchased by the side of Route 80 when a blue Volkswagen Beetle drove up. A thin, mocha-skinned young Black man dressed in denim overalls stepped out of the car. Carmichael recognized Sammy Younge, a student at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute who had become active in campus organizing. Over the previous year, Younge had participated in several SNCC protests, and the two men had become friends. But the last time Carmichael had seen the young collegian, at a birthday party Younge threw for himself in November, he had experienced a change of heart. Drunk on pink Catawba wine, Younge cornered Carmichael and confessed that he was through with activism and wanted to return to partying and preparing for a comfortable middle-class career. Younge “was high that night, and we had a talk,” Carmichael recalled. “He said he was putting down civil rights… and he was going to be out for himself…. So I told him, ‘It’s still cool, you know. Makes me no never mind.’?”

Now Younge seemed eager to join the struggle again. “What’s happening, baby?” Carmichael said, greeting the student with his usual teasing ease. “I can’t kick it, man,” Younge said, referring to the organizing bug. “I got to work with it. It’s in me.” Carmichael chatted with Younge for several minutes, then invited him to stay overnight to help with the tent construction. The next day, Younge approached Carmichael again and confided a new dream. He wanted to attempt in Tuskegee’s Macon County what Carmichael was trying to do in Lowndes County: register enough Black voters so they could form their own political party and elect their own candidates to local offices.

In Carmichael’s territory, that fledgling party already had a name: the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). It also had a distinctive nickname: the “Black Panther Party,” after a symbol that the LCFO had adopted to comply with an Alabama law requiring that political parties choose animal symbols that could be identified on ballots by voters who couldn’t read. “Well, all you have to do is talk about building a Black Panther Party in Macon County,” Carmichael counseled. “See how the idea will hit the people and break that whole TCA thing,” he added, dismissively referring to the Tuskegee Civic Association, a group of elders who had long claimed to speak for Macon County Blacks. Then Carmichael gave Younge a last word of encouragement. “My own feeling was that it would,” Carmichael recalled saying, before he watched Younge climb into his Volkswagen and drive back to Tuskegee.

Although neither Younge nor Carmichael knew it at that moment, they were both about to become major players—one, as a martyr; the other, as a leader and lightning rod—in the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern civil rights era in the 1950s. Over the following year, the story would stretch from Route 80 in Lowndes County across the United States. It would unfold to the east, in that bastion of the Black privilege in Tuskegee; to the northeast, in SNCC’s home base of Atlanta; and due west, on another highway linking Memphis, Tennessee, and Jackson, Mississippi.

To the north, the story would involve a slum neighborhood of Chicago that the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. would select as his next battlefront. Far to the west, two part-time junior college students from Oakland, California, would take inspiration from the black panther experiment in Alabama to launch a radical new movement of their own. After a decade of watching the civil rights saga play out in the South, a restless generation of Northern Black youth would demand their turn in the spotlight. Before the year 1966 was over, the story would alter the lives of a cast of young men and women, almost all under the age of thirty, who in turn would change the course of Black—and American—history.

IN THE STUDY OF THE seismic era known as the 1960s, numerous books have been devoted to individual years. In most cases, this approach has served to weave together different political and social threads that intersected throughout that remarkable decade. But this book will tell the story of the birth of Black Power through the framework of 1966 for more specific historical reasons. First, it was unquestionably the year when the movement as we remember it today took full form. In the spring of 1966, Stokely Carmichael assumed the helm of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and began to redirect SNCC’s focus from peaceful voter registration in the South to a far more sweeping and radical agenda that questioned nonviolence, mainstream politics, and white alliances. During the summer, Carmichael exchanged the defiant chant of “Black Power!” with a crowd in rural Mississippi in a scene that transfixed the media and made him a nationally recognized figure virtually overnight.

In the fall of 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale conceived the “Ten Point Program” founding document of the leather-clad, gun-wielding Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that we remember today. Throughout the year, Dr. King fought an uphill battle to bring his nonviolent, integrationist strategy to Chicago, a flawed campaign that undercut the aura of success surrounding King’s more moderate agenda. In Georgia, Julian Bond, SNCC’s longtime communications director, waged a year-long battle to take a seat in the state legislature after he was banished for opposing the Vietnam War. For young Blacks across the country, it was a humiliating spectacle that deepened their cynicism about the prospects for achieving justice through the two-party political system.

While men received most of the press coverage for their roles in this drama, formidable women played key roles. In the same wild, all-night meeting that resulted in Stokely Carmichael ousting civil rights icon John Lewis as SNCC’s chairman, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, a tough-minded Spelman College graduate, was elected to the number two position of executive secretary. Caught in the middle of one of the year’s most painful episodes—the expulsion of the last remaining whites from SNCC—was Dottie Miller Zellner, a white New York City native who was one of the group’s longest serving and most loyal staffers. Waiting offstage was Kathleen Neal, the daughter of a Black scholar from Texas who dropped out of Barnard College in 1966 to work for SNCC, the first step in a journey that would lead to her becoming a globally recognized name and face as the wife of Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver.

For millions of young Blacks, it was the point at which “Black Consciousness,” as they referred to it, became both a state of mind and a badge of identity. Students of language conventions identify 1966 as the year when Blacks in significant numbers began to reject the label “Negro.” Looking back on this period, Gene Roberts, the white “race beat” reporter for The New York Times, recalled fighting a running battle with his copy desk editors in Manhattan over his decision to stop using that term when referring to young Black militants. By summer, Ebony magazine, the monthly chronicle of Black trends and newsmakers, officially recognized the popularity of the Afro hairstyle with a cover story on “The Natural Look.” While almost all the Black Power leaders cited Malcolm X as an influence, it wasn’t until the middle of 1966, a year and half after Malcolm’s assassination, that his bracing words and powerful life story became known to Blacks and whites of all ages and incomes with the publication of the bestselling $1.25 paperback edition of his posthumous autobiography.

In 1966, the relatively new tools of modern polling captured an ominous turn in racial attitudes. Three years earlier, on the eve of the March on Washington, Newsweek magazine had commissioned pollster Louis Harris to conduct a groundbreaking opinion survey which showed evidence of a widening national belief in racial progress. But when Newsweek had Harris conduct another such poll in the summer of 1966, it registered a stark reversal. Half of Blacks said that change wasn’t happening fast enough, while 70 percent of whites complained that it was coming too fast. After watching TV news footage of another summer of urban race riots, two thirds of whites told Harris’s pollsters that they now opposed any form of Black protest, even nonviolent. “They’re asking too much all at once,” Sandra Styles, a twenty-three-year-old commercial artist from Arlington, Virginia, told a Newsweek reporter. “They should try the installment plan.”

That shift in public opinion, in turn, propelled a change in the political winds that would shape American life for the next half century. Two years after the Democratic Party under Lyndon Johnson had captured dominant control of all three branches of the U.S. government, a white “backlash vote” against Black Power and urban unrest produced huge gains for Republicans in the 1966 midterm elections and set the stage for Richard Nixon’s comeback law-and-order presidential campaign of 1968. In California, a riot in the Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco and an eleventh-hour uproar over a speech by Stokely Carmichael on the University of California at Berkeley campus helped elect Ronald Reagan as governor, putting Reagan on a path to win the White House and further remake the modern conservative movement. In Alabama, the appeal of an even more openly white supremacist brand of politics was demonstrated when George Wallace, the term-limited segregationist governor, encouraged his wife, Lurleen, to run in his place, and the total political novice won in a landslide.

As a narrative framework, focusing on the events of 1966 also makes it possible to reconstruct not just what happened, but how it happened. This book attempts to capture the rich and often messy way that this historic pivot unfolded “in real time,” to use a current expression. No doubt, the sort of broad social forces emphasized by academic historians played an important part. The insidious economic and structural racism of the North differed from the more overt Jim Crow racism of the South. The rising generation of young Northern Blacks didn’t share the religious and deferential traditions of their Southern elders.

Just as important, however, was the timing and sequence of events, and the role of happenstance, both fortunate and tragic. So was the personality of the key players, all of whom had compelling strengths but also conspicuous flaws. As was the case with the earlier civil rights era, white print and television reporters occupied a prominent place in the story. But this time, journalists weren’t welcome witnesses but bewildered outsiders looking on at an uprising that granted them little access and that they were ill-equipped to understand.

Although the Black Power movement continued to gather force and generate headlines into the 1970s, signs of the flameouts and power struggles that proved its eventual undoing were already apparent. For all his dashing good looks and irreverent charm, Stokely Carmichael by the end of 1966 had succumbed to the self-involvement and emotional fragility that would end his tenure as SNCC’s chairman after only one year. At the end of 1966, Eldridge Cleaver was just leaving prison after seven years. But already Cleaver’s jailhouse writings, published in Ramparts magazine and later collected in his bestselling book, Soul on Ice, showed a penchant for self-promotion and competitive egotism that would eventually lead to a destructive feud with Huey Newton after Cleaver joined the Black Panthers. Sensational press coverage of the Black Power phenomenon was already feeding poisonous jealousies, while the FBI was preparing to launch a new campaign of surveillance and dirty tricks that would cripple the movement from that point on.

Yet visible, too, were more positive and prophetic legacies that resonate to this day. The core of Carmichael’s original conception of Black Power—the idea of harnessing the clout of Black voters to elect Black officials in areas where Blacks represented a decisive percentage of the population—has since become manifest in cities and localities across America, and helped lay the groundwork for the nation’s first Black president. The initial mission of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense—to monitor the way police dealt with Blacks in inner-city neighborhoods—looks prescient in the era of #BlackLivesMatter. Many of the tactics and symbols of the Black Power movement were borrowed or adapted, consciously or unconsciously, by the women’s liberation movement and the gay rights movement. Fifty years later, they find echoes even in elements of Trump-era white nationalism, and in roiling debates over the meaning and impact of so-called identity politics.

At the time, some of the best analytical writing about the Black Power movement came from two insightful white scholars: social critic Christopher Lasch and Eugene Genovese, the historian best known for showing how Blacks survived the horrors of slavery by creating their own private social structures. Lasch and Genovese both predicted that the revolutionary political aims of Black Power were bound to fail in a country where the militants, unlike their heroes in Cuba and China, could claim to speak for only a fraction of the Black minority, let alone the larger white majority. But the two scholars also perceived that Black Power spoke to a yearning beyond politics—for a new, distinctly Black culture to replace the one that millions left behind when they moved from the South to the North in the Great Migration of the early and mid-twentieth century. By the end of 1966, glimmers of that new culture could be seen in the first demands for Black Studies programs on college campuses, in the emerging Black Arts Movement, and in the first celebration of the new holiday tradition of Kwanzaa. A half century later, the cultural legacy of Black Power pervades our entire society in the innovations of hip hop music; in other Black aesthetic influences on art, fashion, sports, and language; and in heated debates over how to teach Black history, or whether to teach it at all.

By the end of 1966, much of the tumultuous story of Black Power had yet to be written. But it was already eerily foreshadowed, just as Sammy Younge’s fate was as he drove away from Lowndes County along Route 80 back toward Tuskegee on the eve of that New Year—the last time his friend Stokely Carmichael would see him alive.

In the middle of Alabama, U.S. Route 80, the highway that links Selma and Montgomery, narrows to two lanes as it passes through Lowndes County, deep in the former cotton plantation territory known as the Black Belt. For decades, the deadly reach of the Ku Klux Klan made this slender stretch of open road, surrounded by swamps and spindly trees covered with Spanish moss, one of the scariest in the South. During the historic civil rights march between those two cities in 1965, fewer than three hundred protesters braved the Lowndes County leg, whispering as they hurried through a rainstorm about rumors of bombs and snipers lurking out of sight. When the march ended, cars transporting demonstrators back to Selma drove as fast as they could through Lowndes County, without stopping.

One car didn’t make it. Viola Liuzzo was a thirty-nine-year-old mother of five from Detroit who had answered the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for whites to join the Selma march. After it was over, she was helping drive marchers back from Montgomery along with a young Black volunteer named Leroy Moton. As the two headed back to Montgomery after a drop-off in Selma shortly after nightfall, a red-and-white Chevrolet Impala pulled alongside Liuzzo’s blue Oldsmobile on Route 80. A spray of bullets exploded into the driver’s side window, and the car careened off the road and into a ditch. Moton passed out, and when he came to Liuzzo was slumped lifeless on the bench front seat, her foot still on the accelerator. Moton raced through the darkness to report the attack—which, it would soon emerge, was carried out by four Alabama Klansmen, one of them a paid informant for the FBI.

Two days later, as newspapers across the country ran front-page updates on the murder of the first white woman to die in the civil rights struggle, five young Black organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee slipped unnoticed into Lowndes County on Route 80. The five were there to bring SNCC’s mission of voter registration to the county, an impoverished backwater with the largest percentage of Black residents in the state, but where not a single Black had cast a ballot in more than sixty years. The group’s leader was Stokely Carmichael, a lanky New Yorker with a long, angular nose and heavy-lidded but expressive eyes. His voice mixed the lilt of Trinidad, where he lived until age eleven; the urgency of the Bronx, where he spent his teens; and the polish of Howard University, the distinguished historically Black college from which Carmichael graduated. Over the next eight months, SNCC organizers proved successful enough that white farmers punished Black sharecroppers who registered to vote by evicting them from their land. So it was that, as the year 1965 ended, Carmichael and his comrades found themselves back along Route 80, erecting tents for displaced families while sharecroppers armed with hunting rifles kept watch for night-riding Klansmen.

On the second to last day of December, Carmichael was putting up tents on a six-acre plot that a local church group had purchased by the side of Route 80 when a blue Volkswagen Beetle drove up. A thin, mocha-skinned young Black man dressed in denim overalls stepped out of the car. Carmichael recognized Sammy Younge, a student at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute who had become active in campus organizing. Over the previous year, Younge had participated in several SNCC protests, and the two men had become friends. But the last time Carmichael had seen the young collegian, at a birthday party Younge threw for himself in November, he had experienced a change of heart. Drunk on pink Catawba wine, Younge cornered Carmichael and confessed that he was through with activism and wanted to return to partying and preparing for a comfortable middle-class career. Younge “was high that night, and we had a talk,” Carmichael recalled. “He said he was putting down civil rights… and he was going to be out for himself…. So I told him, ‘It’s still cool, you know. Makes me no never mind.’?”

Now Younge seemed eager to join the struggle again. “What’s happening, baby?” Carmichael said, greeting the student with his usual teasing ease. “I can’t kick it, man,” Younge said, referring to the organizing bug. “I got to work with it. It’s in me.” Carmichael chatted with Younge for several minutes, then invited him to stay overnight to help with the tent construction. The next day, Younge approached Carmichael again and confided a new dream. He wanted to attempt in Tuskegee’s Macon County what Carmichael was trying to do in Lowndes County: register enough Black voters so they could form their own political party and elect their own candidates to local offices.

In Carmichael’s territory, that fledgling party already had a name: the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). It also had a distinctive nickname: the “Black Panther Party,” after a symbol that the LCFO had adopted to comply with an Alabama law requiring that political parties choose animal symbols that could be identified on ballots by voters who couldn’t read. “Well, all you have to do is talk about building a Black Panther Party in Macon County,” Carmichael counseled. “See how the idea will hit the people and break that whole TCA thing,” he added, dismissively referring to the Tuskegee Civic Association, a group of elders who had long claimed to speak for Macon County Blacks. Then Carmichael gave Younge a last word of encouragement. “My own feeling was that it would,” Carmichael recalled saying, before he watched Younge climb into his Volkswagen and drive back to Tuskegee.

Although neither Younge nor Carmichael knew it at that moment, they were both about to become major players—one, as a martyr; the other, as a leader and lightning rod—in the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern civil rights era in the 1950s. Over the following year, the story would stretch from Route 80 in Lowndes County across the United States. It would unfold to the east, in that bastion of the Black privilege in Tuskegee; to the northeast, in SNCC’s home base of Atlanta; and due west, on another highway linking Memphis, Tennessee, and Jackson, Mississippi.

To the north, the story would involve a slum neighborhood of Chicago that the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. would select as his next battlefront. Far to the west, two part-time junior college students from Oakland, California, would take inspiration from the black panther experiment in Alabama to launch a radical new movement of their own. After a decade of watching the civil rights saga play out in the South, a restless generation of Northern Black youth would demand their turn in the spotlight. Before the year 1966 was over, the story would alter the lives of a cast of young men and women, almost all under the age of thirty, who in turn would change the course of Black—and American—history.

IN THE STUDY OF THE seismic era known as the 1960s, numerous books have been devoted to individual years. In most cases, this approach has served to weave together different political and social threads that intersected throughout that remarkable decade. But this book will tell the story of the birth of Black Power through the framework of 1966 for more specific historical reasons. First, it was unquestionably the year when the movement as we remember it today took full form. In the spring of 1966, Stokely Carmichael assumed the helm of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and began to redirect SNCC’s focus from peaceful voter registration in the South to a far more sweeping and radical agenda that questioned nonviolence, mainstream politics, and white alliances. During the summer, Carmichael exchanged the defiant chant of “Black Power!” with a crowd in rural Mississippi in a scene that transfixed the media and made him a nationally recognized figure virtually overnight.

In the fall of 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale conceived the “Ten Point Program” founding document of the leather-clad, gun-wielding Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that we remember today. Throughout the year, Dr. King fought an uphill battle to bring his nonviolent, integrationist strategy to Chicago, a flawed campaign that undercut the aura of success surrounding King’s more moderate agenda. In Georgia, Julian Bond, SNCC’s longtime communications director, waged a year-long battle to take a seat in the state legislature after he was banished for opposing the Vietnam War. For young Blacks across the country, it was a humiliating spectacle that deepened their cynicism about the prospects for achieving justice through the two-party political system.

While men received most of the press coverage for their roles in this drama, formidable women played key roles. In the same wild, all-night meeting that resulted in Stokely Carmichael ousting civil rights icon John Lewis as SNCC’s chairman, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, a tough-minded Spelman College graduate, was elected to the number two position of executive secretary. Caught in the middle of one of the year’s most painful episodes—the expulsion of the last remaining whites from SNCC—was Dottie Miller Zellner, a white New York City native who was one of the group’s longest serving and most loyal staffers. Waiting offstage was Kathleen Neal, the daughter of a Black scholar from Texas who dropped out of Barnard College in 1966 to work for SNCC, the first step in a journey that would lead to her becoming a globally recognized name and face as the wife of Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver.

For millions of young Blacks, it was the point at which “Black Consciousness,” as they referred to it, became both a state of mind and a badge of identity. Students of language conventions identify 1966 as the year when Blacks in significant numbers began to reject the label “Negro.” Looking back on this period, Gene Roberts, the white “race beat” reporter for The New York Times, recalled fighting a running battle with his copy desk editors in Manhattan over his decision to stop using that term when referring to young Black militants. By summer, Ebony magazine, the monthly chronicle of Black trends and newsmakers, officially recognized the popularity of the Afro hairstyle with a cover story on “The Natural Look.” While almost all the Black Power leaders cited Malcolm X as an influence, it wasn’t until the middle of 1966, a year and half after Malcolm’s assassination, that his bracing words and powerful life story became known to Blacks and whites of all ages and incomes with the publication of the bestselling $1.25 paperback edition of his posthumous autobiography.

In 1966, the relatively new tools of modern polling captured an ominous turn in racial attitudes. Three years earlier, on the eve of the March on Washington, Newsweek magazine had commissioned pollster Louis Harris to conduct a groundbreaking opinion survey which showed evidence of a widening national belief in racial progress. But when Newsweek had Harris conduct another such poll in the summer of 1966, it registered a stark reversal. Half of Blacks said that change wasn’t happening fast enough, while 70 percent of whites complained that it was coming too fast. After watching TV news footage of another summer of urban race riots, two thirds of whites told Harris’s pollsters that they now opposed any form of Black protest, even nonviolent. “They’re asking too much all at once,” Sandra Styles, a twenty-three-year-old commercial artist from Arlington, Virginia, told a Newsweek reporter. “They should try the installment plan.”

That shift in public opinion, in turn, propelled a change in the political winds that would shape American life for the next half century. Two years after the Democratic Party under Lyndon Johnson had captured dominant control of all three branches of the U.S. government, a white “backlash vote” against Black Power and urban unrest produced huge gains for Republicans in the 1966 midterm elections and set the stage for Richard Nixon’s comeback law-and-order presidential campaign of 1968. In California, a riot in the Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco and an eleventh-hour uproar over a speech by Stokely Carmichael on the University of California at Berkeley campus helped elect Ronald Reagan as governor, putting Reagan on a path to win the White House and further remake the modern conservative movement. In Alabama, the appeal of an even more openly white supremacist brand of politics was demonstrated when George Wallace, the term-limited segregationist governor, encouraged his wife, Lurleen, to run in his place, and the total political novice won in a landslide.

As a narrative framework, focusing on the events of 1966 also makes it possible to reconstruct not just what happened, but how it happened. This book attempts to capture the rich and often messy way that this historic pivot unfolded “in real time,” to use a current expression. No doubt, the sort of broad social forces emphasized by academic historians played an important part. The insidious economic and structural racism of the North differed from the more overt Jim Crow racism of the South. The rising generation of young Northern Blacks didn’t share the religious and deferential traditions of their Southern elders.

Just as important, however, was the timing and sequence of events, and the role of happenstance, both fortunate and tragic. So was the personality of the key players, all of whom had compelling strengths but also conspicuous flaws. As was the case with the earlier civil rights era, white print and television reporters occupied a prominent place in the story. But this time, journalists weren’t welcome witnesses but bewildered outsiders looking on at an uprising that granted them little access and that they were ill-equipped to understand.

Although the Black Power movement continued to gather force and generate headlines into the 1970s, signs of the flameouts and power struggles that proved its eventual undoing were already apparent. For all his dashing good looks and irreverent charm, Stokely Carmichael by the end of 1966 had succumbed to the self-involvement and emotional fragility that would end his tenure as SNCC’s chairman after only one year. At the end of 1966, Eldridge Cleaver was just leaving prison after seven years. But already Cleaver’s jailhouse writings, published in Ramparts magazine and later collected in his bestselling book, Soul on Ice, showed a penchant for self-promotion and competitive egotism that would eventually lead to a destructive feud with Huey Newton after Cleaver joined the Black Panthers. Sensational press coverage of the Black Power phenomenon was already feeding poisonous jealousies, while the FBI was preparing to launch a new campaign of surveillance and dirty tricks that would cripple the movement from that point on.

Yet visible, too, were more positive and prophetic legacies that resonate to this day. The core of Carmichael’s original conception of Black Power—the idea of harnessing the clout of Black voters to elect Black officials in areas where Blacks represented a decisive percentage of the population—has since become manifest in cities and localities across America, and helped lay the groundwork for the nation’s first Black president. The initial mission of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense—to monitor the way police dealt with Blacks in inner-city neighborhoods—looks prescient in the era of #BlackLivesMatter. Many of the tactics and symbols of the Black Power movement were borrowed or adapted, consciously or unconsciously, by the women’s liberation movement and the gay rights movement. Fifty years later, they find echoes even in elements of Trump-era white nationalism, and in roiling debates over the meaning and impact of so-called identity politics.

At the time, some of the best analytical writing about the Black Power movement came from two insightful white scholars: social critic Christopher Lasch and Eugene Genovese, the historian best known for showing how Blacks survived the horrors of slavery by creating their own private social structures. Lasch and Genovese both predicted that the revolutionary political aims of Black Power were bound to fail in a country where the militants, unlike their heroes in Cuba and China, could claim to speak for only a fraction of the Black minority, let alone the larger white majority. But the two scholars also perceived that Black Power spoke to a yearning beyond politics—for a new, distinctly Black culture to replace the one that millions left behind when they moved from the South to the North in the Great Migration of the early and mid-twentieth century. By the end of 1966, glimmers of that new culture could be seen in the first demands for Black Studies programs on college campuses, in the emerging Black Arts Movement, and in the first celebration of the new holiday tradition of Kwanzaa. A half century later, the cultural legacy of Black Power pervades our entire society in the innovations of hip hop music; in other Black aesthetic influences on art, fashion, sports, and language; and in heated debates over how to teach Black history, or whether to teach it at all.

By the end of 1966, much of the tumultuous story of Black Power had yet to be written. But it was already eerily foreshadowed, just as Sammy Younge’s fate was as he drove away from Lowndes County along Route 80 back toward Tuskegee on the eve of that New Year—the last time his friend Stokely Carmichael would see him alive.

Recenzii

"Whitaker has a journalist’s understanding of the difference between merely documenting the facts and using them to tell a story, and his sober yet crisp prose pulls the reader along with nary a lull."

"Excellent. . . . [Whitaker] writes with the eye of a journalist and ear of a poet. . . . A refreshing history of the Black Freedom Struggle during the year when the dominant idea about racial progress transitioned from an emphasis on non-violent direct action toward a demand for Black self-determination, Black consciousness, and Black pride."

“I was in high school in 1966, and it felt like the edge of history. In his brilliant new book, Saying It Loud, Mark Whitaker has taken me back there, and the journey is both enthralling and a riveting reminder of the tumult, inspiration, and potent possibilities of the Black Power movement. It's also novelistic in its fully realized human portraits of the movement's backstory. I can't say it any louder: this is not only a compelling read; it's essential for understanding where we started and where we might find lessons in determining where we go from here.”

“A fresh take on what Whitaker rightly describes as ‘the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern Civil Rights era.”

“The years that Mark Whitaker chronicles in Saying It Loud were years I well knew as a young reporter and also as a Black Southerner who came out of the Civil Rights Movement when much of the complicated (and yes sometimes disturbing) history he delves into was being made. . . . What Saying It Loud provides, especially for the Black Lives Matter generation, is history that will help them avoid the pitfalls of their predecessors as well as a road map to the more perfect union this country has long promised but has not yet achieved."

“With surgical precision and poetic verve, Mark Whitaker’s Saying It Loud limns the anatomy of racial chaos, group conflict and organizational convulsion that transformed 1966 into a seminal year of Black resistance. . . . Brilliantly tracks the rise and fall of Black Power and how its lessons echo across the decades and thunder in today’s headlines.”

“At once eloquently intimate and bracingly expansive, Saying It Loud is a tour de force. Mark Whitaker has produced a provocatively eloquent and original work of narrative history that inspires us to look upon the past with new eyes.”

"Excellent. . . . [Whitaker] writes with the eye of a journalist and ear of a poet. . . . A refreshing history of the Black Freedom Struggle during the year when the dominant idea about racial progress transitioned from an emphasis on non-violent direct action toward a demand for Black self-determination, Black consciousness, and Black pride."

“I was in high school in 1966, and it felt like the edge of history. In his brilliant new book, Saying It Loud, Mark Whitaker has taken me back there, and the journey is both enthralling and a riveting reminder of the tumult, inspiration, and potent possibilities of the Black Power movement. It's also novelistic in its fully realized human portraits of the movement's backstory. I can't say it any louder: this is not only a compelling read; it's essential for understanding where we started and where we might find lessons in determining where we go from here.”

“A fresh take on what Whitaker rightly describes as ‘the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern Civil Rights era.”

“The years that Mark Whitaker chronicles in Saying It Loud were years I well knew as a young reporter and also as a Black Southerner who came out of the Civil Rights Movement when much of the complicated (and yes sometimes disturbing) history he delves into was being made. . . . What Saying It Loud provides, especially for the Black Lives Matter generation, is history that will help them avoid the pitfalls of their predecessors as well as a road map to the more perfect union this country has long promised but has not yet achieved."

“With surgical precision and poetic verve, Mark Whitaker’s Saying It Loud limns the anatomy of racial chaos, group conflict and organizational convulsion that transformed 1966 into a seminal year of Black resistance. . . . Brilliantly tracks the rise and fall of Black Power and how its lessons echo across the decades and thunder in today’s headlines.”

“At once eloquently intimate and bracingly expansive, Saying It Loud is a tour de force. Mark Whitaker has produced a provocatively eloquent and original work of narrative history that inspires us to look upon the past with new eyes.”

Descriere

Journalist and author Mark Whitaker describes the momentous year when the Civil Rights movement split as a new sense of Black identity embodied by Stokely Carmichael and the slogan "Black Power" redefined the Civil Rights movement and challenged the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis.