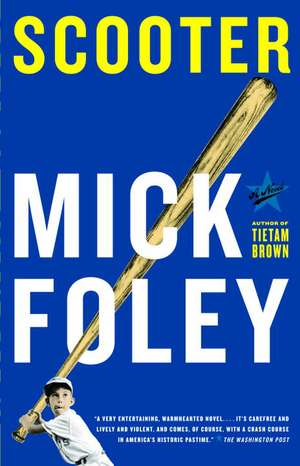

Scooter

Autor Mick Foleyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2006

Preț: 81.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 123

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.66€ • 16.18$ • 13.03£

15.66€ • 16.18$ • 13.03£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096800

ISBN-10: 1400096804

Pagini: 302

Dimensiuni: 144 x 187 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400096804

Pagini: 302

Dimensiuni: 144 x 187 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Mick Foley grew up in East Setauket, New York. He is the author of Tietam Brown, Foley Is Good: And the Real World Is Faker Than Wrestling and Have a Nice Day!: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks, as well as three children's books. He wrestled professionally for fifteen years and was a three-time WWE champion. Foley lives with his wife and four children on Long Island.

Extras

1964

[ 1 ]

“Dad, what’s a dick?” I was four years old when I let that question loose on my unsuspecting dad, but oddly, I don’t think I’ve given that somewhat strange inquiry a second thought until recently. I’m not sure what seems odder—the ridiculous nature of the question or the fact that my dad never batted an eye upon its delivery. Didn’t bat an eye, didn’t crack a smile, didn’t even turn his head. Instead, he paused, measuring his words, and softly said, “That’s a person who does bad things, son, kind of like a jerk.”

That was the Bronx in 1964, aboard the Third Avenue El train that was only part of a long journey from the northeast corner of the borough to Highbridge, which was just a little northwest of Yankee Stadium, where I lived in a small three-bedroom house on Shakespeare Avenue.

Thirty days earlier, I’d come home from school to find my mother in a state of near shock, my father sitting by her side on our faded red love seat, his shoulder her only visible means of support. My little sister’s slapping soles and happy babbling stood as a stark contrast to the dark aura that hung heavy in our tiny living room.

My father broke the news. My grandfather, a fireman for over thirty years and my roommate for my entire life, had been in an accident. His head, face, chest and arms had been severely burned, and his chances for living were questionable.

I had never been alone before that night. Surrounded by my grandfather, I’d always felt safe. Maybe I should say surrounded by my grandfather and Joe D., for his visage was everywhere. Grinning down at me from every conceivable angle. Following through on his textbook swing as he watched another shot sail out of the seemingly endless confines of Death Valley in left center. His arm around Marilyn, who had played a part in prompting my surprise dick question.

Joe DiMaggio scared me that night. To a young child all alone, he appeared to be glaring, his awkward grin seemed to be taunting me, the gaps in his smile looming large, impossibly large, as if they could inhale a young boy and leave not a trace.

I longed for my grandfather, his soft touch, his smell, his sound. The touch of his thick, calloused fingers tousling my hair. I missed his soft, gentle brogue, an ode to his ancestral homeland, even though his ancestors had left Ireland a century before. An accent like his was not uncommon in Highbridge, a strong Irish enclave, but the brogues, like the Irish, were starting to fade and within a short time, like the Irish themselves, would disappear from its streets.

Grandpa used to say that my father had a map of Ireland on his face. Which, after some confusion, I came to learn meant he had traditional Irish features. Fair hair, rusty blond but not quite red, freckles and green eyes. My map wasn’t quite so detailed. I think I had my mother’s face, dark, almost exotic. The result, I’m told, of Spanish blood passed through my veins some centuries before, on some forgotten branch of my mother’s Irish family tree.

I was never sure of Grandpa’s map. To me he never looked Irish, or of any other ethnic group, for that matter. He was Grandpa, after all, which meant to my young, unknowing eyes he’d always looked just . . . old. He was old, but I missed him.

I missed the Scooter as well. Phil Rizzuto, my namesake, was, from April until fall, like a third roommate. A third roommate who showed up each night around seven and wished happy birthdays to strangers and once in a while mentioned the ball game. An old Philco radio, from which the Scooter’s voice would emerge, sat on a small table by Grandpa’s bed. That night it was silent . . . and I missed the Scooter.

I lay awake thinking about Grandpa. Long after the hour when the crack of the bat and happy birthdays to strangers would usually lull me to sleep, I thought of that man. I used the prayers that I’d learned at Sacred Heart Church. I used them over and over, until I knew they would work. I prayed for all his late-night screams to stop. Those infrequent, mournful cries that had been frightening me for as long as I could remember. Those screams that left him cold, but sweating. I prayed for those burns to all go away. So that Grandpa would be back. Back in our house and back in my room. Where he belonged.

I got out of my bed well before dawn. I turned my head from side to side, studying Joe D.’s various likenesses, hoping he wouldn’t decide to swoop down for the kill. I looked out of my window. First across the street at the three-story brick walk-ups, where during daylight hours mothers rested their elbows on pillows to watch over their kids. I looked to my left down the steep hill that led to P.S. 114. The hill where I’d sat on my grandfather’s lap as he steered the Flexible Flyer. Where my little-boy laughs had come out in great clouds of steam. Where my mother had waited, with her hands on her hips, saying her child was too young to sled down such a steep hill. This winter, she said, she might reconsider. But when this winter came, would Grandpa still be alive?

I grew up thinking that my mom babied me, because she wouldn’t let me have the run of the streets like other kids did. But on that first night without Grandpa, I needed my mother. I needed her warmth, her love, and the scent of Wrigley’s Doublemint Chewing Gum and cigarettes with each breath she let go.

I walked out my door and into the hall that separated my sister Patty’s room from mine. I looked for my sister inside her room, though I knew better. She was nearly three now, but she still slept in a crib in my parents’ room, a subject that for over a year had been a bone of contention between my mom and my dad. A bone, it turned out, that my mom always got. For despite the fact that my father had spent two full weekends of the previous summer wallpapering Patty’s room with a pattern of fairies and field mice, the little girl remained a fixture in my parents’ bedroom.

Weekends were not something that my dad parted with lightly. Weekends meant ball games and ball games meant beer, and my father loved both. Nothing extreme, just a six-pack of Ballantine, the Yankees’ proud sponsor, over the course of nine innings. Then would come dinner, and my father would glow, from both his game and his beer. Back in those days the Yankees didn’t lose often, but I think more than the outcome, the game’s timeless rhythm put him at peace. I always hated for Sundays to end, for I knew that when they did, my dad had to go to work across the river in Harlem, walking a beat from four until midnight.

Sure enough, no sister there. I proceeded with care down the short hall. Still on the lookout for Joe D. I had heard of the way he patrolled center field, how surefire doubles met their end in his glove. How he was so fleet of foot that he never needed to dive.

I opened the door. As quietly as possible with two shaking hands. I heard a head stir.

“Scooter, is that you?”

“Yeah, Mom, it’s me.”

“Are you okay?”

“I’m a little bit scared.”

I could almost hear her smile in the darkness. She said, “I guess you’d better come here.”

I practically dove into her arms, then faded off into sleep as she tickled my back.

“Dad?”

“Yes, son?”

“What does ‘fuck’ mean?”

We were walking down 167th, only a few blocks from home, and we hadn’t talked much since we got off our train. In fact, I think my father had been silent since shedding some light on “dick’s” definition. His reaction, again, was slightly low key, considering the subject.

“That’s when someone does something bad to somebody else. It usually concerns money. Kind of like cheating.”

[ 2 ]

My grandfather couldn’t have visitors for those first thirty days. I guess due to the threat of infection. He’d nearly died that first night. My dad had grown silent and sullen during the course of that month. On a couple of nights I heard beer tabs in the darkness, a prescription for sorrow after a long night of work.

My dad had rejoiced when he’d gotten the phone call. My grandfather’s life was no longer in danger. He’d been transferred to Bronx Psychiatric to undergo testing, but at least he was alive and, better yet, could have guests.

My father woke me up early on the day of our visit. He didn’t smile often, at least not in matters that didn’t concern a ball game. But on this day in question his smile was a wide one.

“Scooter, wake up.”

I blinked once or twice and then turned off Grandpa’s Philco, which I had placed next to my bed a week after he’d left.

“Hi, Dad,” I said.

“Guess who we’re seeing today?”

“Grandpa,” I said, my voice high with excitement.

“You betcha,” he said, then he glanced around my room, allowing his eyes to take in every single shot of Joe D. “Yes, we’re gonna see Grandpa, but we’re gonna see someone else too.”

My dad was so excited that I thought he might cry. Just seeing Grandpa would be the absolute best, but my dad was holding a secret, as if things could somehow get better.

He said, “Go ahead, guess.”

My mind drew a big blank. Once again, my dad’s eyes darted around the room.

I shook my head, clearly puzzled, then said, “I don’t know.”

My dad’s face formed a frown, but it was quickly erased by a grin even bigger than the one I’d awoken to. “I’ll give you a hint—he’s on your wall.”

“Batman!” I yelled. “I’m gonna meet Batman!” I looked over my bed at a picture of TV’s newest sensation that my mom had cut out of the paper and taped to the wall.

“No, Scooter, not Batman.” My dad played it off as if he was amused, but even at the age of four I could hear the disappointment in his voice. This was his moment, and I was in the process of ruining it, all due to Bruce Wayne’s alter ego.

I looked at the walls. Aside from Batman, a faded, yellowed snapshot of a pretty teenage girl and a 1959 photo of my father in the Daily News, the choices were slim. There was a photo of me, in front of the Babe’s monument in the outfield at the stadium, looking just a tad more than terrified, I think due to the fact that I thought the Sultan of Swat was buried right there and that I was posing for photos on top of his grave. After that, there was no one except—

“Joe D.?” I asked, with a level of enthusiasm usually reserved for the discovery of lima beans on one’s dinner plate.

“That’s right. Joe D.,” he said, making up for my lack of excitement by doubling his own. “But it gets even better. Guess where we’re meeting him?”

I had no idea, and told him as much. My answer didn’t faze him. My father was on a roll now, savoring a high that usually came only with a frank and a cold one during our yearly pilgrimage to the stadium, and neither my ignorance nor my apathy was going to slow him down. “Today!—You—and I—are going . . . to . . . Freedomland!”

“Freedomland!?” I yelled.

“Freedomland Indeedomland!” he yelled back.

I temporarily forgot about my poor grandfather, so blinded with excitement was I. Freedomland was like a dream. Farther away from home than I’d ever been. All the way on the other side of the Bronx. I had begged my dad to take me there for as long as I could remember, ever since hearing “Mommy and Daddy, take my hand, take me out to Freedomland” on the radio. Ever since hearing Johnny Horton sing the Freedomland theme song, “Johnny Freedom,” on the jukebox at Rossi’s Sandwich Shop. Today the dream was real. My father seemed to feed off my euphoria, detailing with relish just how our day would proceed.

“We’ll head down to Cozy Corners for a new ball and a coffee. How ’bout an egg cream while we’re at it? Then we’re off for the train to Gun Hill, take the bus to Baychester, and BAM! Before you know it, you’re merry-go-roundin’ in Kandy Kane Lane. Then after you’ve had more fun than one little guy can stand, BAM! We go see Joe D.!”

[ 3 ]

The day went just as my dad had planned. BAM! I rode the merry-go-round in Kandy Kane Lane. I didn’t know then that Freedomland was in its dying days. That I’d never see it again. It didn’t occur to me that 1909 Cadillacs didn’t belong on the Civil War battlefield, or that Elsie the Cow was at the World’s Fair. I only knew that souvenirs were a quarter, and my dad was in the mood to spend. A mood I’d never seen him in before, and would never see again. Sure enough, I had more fun than one little guy could stand, and then, BAM!, we went to see Joe D. with Grandpa’s old Philco tucked underneath my father’s arm.

My dad had told me how he and Grandpa used to wait for hours after games for Joe D. to emerge. Just to see him walk by on his way to the car. Just to say hello, maybe get him to sign a yearbook or a ball. But Joe D. never emerged. My grandfather wondered if the stadium had some secret underground passageway so that Joe D. could escape undetected. Kind of like the secret exit from the Batcave, I guess.

They had never met Joe D., but they sure had met a lot of other guys. Yogi. Larsen. Lopat. Bauer. Mantle too. My father showed me his collection a few times. Two decades of Yankee royalty, their signatures scribbled on a cavalcade of memorabilia—yearbooks, scorecards, ticket stubs, balls, gloves, Spaldeens, even a Krum’s menu. But the crown jewel of my dad’s collection was his photo of the Scooter, 1950, the year he won the MVP, posed with my dad, both of them smiling.

The Scooter had driven in the winning run that day, bunted it in, a suicide squeeze, and when he posed for the picture, he let my dad hold the bat. Then he walked away. He just walked away and let my dad have the bat.

My dad got his bat. I got his name. Why couldn’t Rizzuto have taken DiMaggio’s tunnel on that fateful day?

But on this day, for the first time, my father would see the great Yankee Clipper. Just as soon as he waited in a line several hundred feet long, where die-hard Yankee fans all waited for the greatest living ballplayer to write down his name. All except the guy right in front of us, who had nothing to be signed. Which struck my dad as rather strange.

“Whattaya want Joe to sign?” he asked the guy.

“Nothin’,” the guy said.

“Nothin’?”

“Nah, nothin’.”

My dad hadn’t inherited his father’s brogue, but he didn’t have a typical “Noo Yawk” accent either. Very few people in Highbridge did. I escaped somewhat unscathed as well. Some Bronxites, however, including my mother, didn’t get off quite so lucky. This guy, the “nothin’ ” guy, may have been the unluckiest of all.

My dad didn’t quite know what to make of the guy, who didn’t have a kid with him and didn’t appear to be a connoisseur of amusement park rides. The guy was definitely there to see Joe D., yet had “nothin’ ” to sign. It didn’t make sense.

A few more minutes went by. Joe was in sight now, or at least the green curtain that he was sitting behind was in sight. Apparently, you had to pay to see Joe. There were no free peeks at the Clipper. Even the “nothin’ ” guy had paid his two bucks—it was a shame that he’d leave with “nothin’ ” to show for it.

Curiosity finally got the better of my dad. He didn’t want to ask, but I guess he felt like he had to.

“Whattaya here for if you don’t want Joe to sign?” my father asked.

The guy smiled. Not a friendly smile, just a little corner-of-the-mouth smile. He was a big guy, much bigger than my dad. I thought there might be trouble. After a tense moment, the guy seemed to relax. His smile even became friendly.

“Hey, buddy,” the guy said, “I just wanna shake Joe’s hand.”

The guy and my dad then proceeded to reminisce about great Joe D. moments. Great Joe D. hits, great Joe D. catches. Great Joe D. wives.

Gradually, the curtain got closer. I could see Joe’s silhouette as he wrote down his name, could see the pen performing its elegant arcs, could see the cigarette as he brought it to his lips for a long, refreshing drag. We were next. Yes! We were next! I’d never even seen Joe play, but we were next. His pictures scared the crap out of me, but we were next. I could hear Joe’s voice, rich and resonant, as he spoke to the guy in front of us—the “nothin’ ” guy.

“What would you like me to sign?” the Clipper asked.

“Nothin’.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothin’.”

“Excuse me?”

“Nothin’, I got nothin’ to sign.”

“I’ve got a piece of paper here. I’ll just sign that.”

“No, I don’t want nothin’ signed.”

I could see Joe’s silhouette stiffen. I could see the silhouettes of Joe’s two beefy security guards stiffen too. When Joe spoke, it was with agitation.

“If you don’t want me to sign anything, why are you here?”

I could see the nothin’ guy shrink. Even from a seated position, Joe D. suddenly loomed much larger than life. Much larger than the recipient of Joe’s very well-mannered bile, who now fumbled for words.

The “nothin’ ” guy finally said, “I just wanna shake your hand.”

“You want to shake my hand?” Joe asked, his disbelief mingling with sarcasm.

“Yeah, how ’bout it?” I could see the guy stick his arm out.

A deep voice rang out, very official. “Mr. DiMaggio, would you like me to remove this man?”

“No, that’s okay,” Joe said. He now sounded intrigued, slightly amused. “This gentleman just wants to shake my hand. Isn’t that correct?”

“Yeah, so how ’bout it?” The guy stuck his hand out again.

“Hold on a moment,” Joe said. He was having fun now, toying with the big guy, sitting back and watching him squirm. He was like a fish on Joe’s hook and Joe was going to reel him in, just as he had done in his youth on the docks of San Francisco. It was just too bad that Freedomland’s San Francisco area had closed down. The irony would have been incredible—Joe D. baiting and hooking this poor slob right on Fisherman’s Wharf.

I could see Joe put his arms behind his head. He leaned back and said, “Let me get this straight. You paid two dollars to get into the park. Then you paid two dollars to stand in line. Then, after standing in line for quite a while, you tell me that you just want to shake my hand. Is that correct?”

“Yeah, Joe, that’s right.”

“Why?”

“I got my reasons.”

“I would like to know what those reasons are.”

“No, Joe, I don’t think you do.”

“Yes, as a matter of fact I do.” Joe sat up now. He wasn’t quite as composed. The fish was fighting back. Joe reached for a verbal harpoon. And hurled it. “Sir, either you tell me now or I’ll have you escorted from the park.”

“You really wanna know?”

“Yes.”

“Ya sure?”

“Yes, I’m sure.”

The guy let out a breath of air. Then let Joe have just a little bigger dose of truth than he was prepared to handle.

“I just wanted to shake the hand that shook the dick that fucked Marilyn Monroe.”

The Clipper jumped up and stormed off through a steel door and slammed it shut behind him. I wasn’t sure where it led, an office perhaps, maybe a closet, but I was reasonably sure that things started breaking behind that steel door.

“Dad, why is Joe mad?” I asked.

My dad didn’t say a word.

The big guy who wanted “nothin’ ” signed didn’t look so big as he was being whisked away. He was kind of doubled over, maybe from the punches that Joe’s two security guards directed at his midsection. I hadn’t seen punches thrown in quite a while. My mom didn’t let me watch bad shows on TV, and my dad was under strict orders to get up and switch the channel when one of baseball’s bench-clearing brawls broke out.

Following the “nothin’ ” guy’s departure, Joe D.’s security informed the line that the autograph session was over. Refunds were offered. But my dad didn’t want a refund—he wanted Joe. I watched my father’s face as he contemplated his course of action. Wrinkles on his brow, adding a decade to his twenty-seven years. Biting down on his lower lip, a mannerism that would become increasingly more prevalent in his demeanor as the years went by. His way of fighting off natural instincts of aggression in favor of a cooler head.

“Scooter, stay here for just a second,” he said as he stepped out of a line that was fast dissolving and approached the protective layer of Joe’s men.

My dad put a hand on one man’s broad shoulder. The hand was slapped away. My father tried again. Again his gesture was rebuffed. My dad reached for his pocket. His holster, I thought. My dad’s drawing his gun. I could almost read the headlines. a death at freedomland. But when his hand came out, it didn’t hold a gun. It held a badge instead. A badge that got the guy’s attention and a sympathetic ear for my father’s real-life woe. When my dad returned minutes later, the line was all but gone. Gone except for me, and a somewhat angry fan who was yelling at Joe’s door that Ted Williams should have been MVP back in ’41.

“Joe will see us in a little while,” my father said.

A little while, it turned out, was quite a while. Forty-seven minutes, to be exact. Long enough for me to replay the day’s events in my mind several times. I thought of the egg cream, the train, the bus, the rides. I thought of the big guy who didn’t want nothin’ signed and the sound of things breaking behind the door Joe had slammed. But I kept coming back to the way I had felt when my dad reached for his badge. I had really believed that he was going to spray Freedomland full of lead. And I thought it would have been justified. But pulling a gun was against my dad’s nature. I had heard him explain on many occasions how he intended to put in twenty years on the force without ever firing. It was an intention that had put him at odds right away with his father-in-law, a retired First Grade detective in New York’s Four-O district in Motthaven, a close Bronx neighbor of Highbridge. Apparently, my mother’s father had amassed an impressive arrest and body count during his days on the force, and he had showed very little understanding or respect for my father’s somewhat more humanitarian approach to law enforcement. My dad walked a beat on the mean streets of Harlem, and he did so without fear and with a heartfelt belief that every life was worth helping. I guess a Joe D. tantrum at the fun park was not such a big deal after all.

The security guy put his hand on my dad’s shoulder. “The Dago will see you” was all that he said.

I followed my dad, who had the Philco under his arm, as he made his way to Joe D.’s steel door. I looked at Joe’s curtain as I passed it by and wondered if Grandpa might like a few of Joe’s smoked butts to keep in his room. I thought that he would, but I was too scared to ask.

The heavy door opened, and Joe D. himself looked straight into my eyes. He didn’t look goofy or awkward like he had in ’41, when he’d hit in fifty-six straight. And I was reasonably sure that he wouldn’t inhale me. He just looked sad and lonely, sitting behind an ugly gray desk whose contents lay scattered and broken and battered on the dirty tile floor. There was a hole in the wall that looked newly formed.

Joe D. spoke with a whisper, his voice barely audible as he expressed his regret at what had transpired. Then he expressed his remorse for my grandfather’s health. “I hope this will help,” said the Clipper, as he took the ball from my father and rolled it in the palm of his left hand until he found the sweet spot. When he picked up his pen, I could see his right knuckles were bleeding.

Joe signed his name with the ease of a man who had done such a task thousands of times. As he did, I studied his hands and saw one drop of blood make a long, lonely trip from the wound’s point of origin to the tip of his finger to the point of his pen. Black ink and Joe’s blood became one and the same as he looped his last “o,” and it wasn’t until later, on our short cab ride to Bronx Psychiatric, that the “o” became smudged and the red scarred the white sphere.

[ 4 ]

I wasn’t prepared for what I saw in room 317. The sight of my grandfather lying in bed, his face swathed in gauze, not a trace of skin showing. I wasn’t prepared for the sounds of that place either, distant screams that seemed to pull at my feet, as if trying to drag me through concrete, to unknown horrors below. I wanted to leave, to get out of that place, and I started to tug on my father’s coat sleeve. I loved my grandfather, but this wasn’t him. This man was a monster, a mummy, a ghoul. I tugged the sleeve harder.

My father glanced down, more hurt than annoyed. “Say hello to your grandpa” was all he said. But I couldn’t speak. I just turned away. The thing in the bed couldn’t speak either. Was it even alive?

My dad did the talking. He talked to a ghoul. He talked to an unseeing, unfeeling, unmoving ghoul. The Bronx Bombers in five, the Cardinals couldn’t stack up. Gibson’s heat was no match for Whitey’s best stuff. Flood couldn’t lace the Mick’s shoes in center. He placed the old Philco on a shelf by the bed. Game number one of the ’64 Series began the next day. He thought Grandpa might like to listen. But Grandpa was gone. And the thing in his place wasn’t responding.

My dad’s hands were shaking as he reached for Joe’s ball. His red, swollen eyes were rimmed with welled tears. He looked like he’d aged since we entered the room. His voice shook when he spoke.

“I got somethin’ for you.”

He took out the ball and rewrote the day’s history as he fought back his tears.

“I saw Joe D. today, Dad. Yeah, can you believe it? Me and Scooter saw him. I took Scooter to Freedomland, he had the time of his life. You gotta see the place, Dad. You’d love it, I swear. Scooter helped put out the great fire in Chicago. He wanted to help so he could be just like you. Then, as we’re eatin’ Chinese in San Fran, Scooter tugs on my sleeve. I say, ‘Scooter, hold on, I’m tryin’ to eat.’ But he tugs on my arm, so I look up at your roommate and he’s pointin’ out in the street, over by the Seal Pool. So I look where he’s pointin’ and who do I see? Joe D. ‘Yeah, Joe D.’ I know Joe likes his privacy, but I couldn’t resist, so I walk on over and I say hello and I tell him my father is his number one fan. And I’ll tell you what, Dad, Joe couldn’t have been nicer. He even pulled out a ball and signed it for you. And I got it right here. Isn’t that just how it went, son?”

I’d never once heard my dad tell a lie, let alone ten in a row, but in spite of that fact, I nodded my head. I don’t know why. It’s not like the monster could see me. Or hear one word that my father said. My father held out the ball . . . and the thing moved its hand. At first it moved slowly, hardly at all, but it moved just the same. The hand started to rise. I felt a lump in my throat. My father lowered the ball. The thing’s hand met it halfway. The thing was my grandpa, and he was touching the ball. My dad wrapped Grandpa’s fingers around Joe D.’s smudged ball and, just for a moment, the hand held it there. Then the hand slowly lowered and put the ball to its heart. My knees went weak and I thought I would fall. I leaned on my father’s leg to help me stay up, and he reached down for me and stroked my short hair. I looked up at my dad and there were tears on his face.

[ 5 ]

My father was silent the entire way home, my two poignant questions being the trip’s only exceptions. A few kids were playing stoopball as we approached our little blue house. Darkness was falling and Shakespeare was quiet, almost eerily so. My dad waved to a neighbor, whose day probably hadn’t been quite as hectic as ours. The lights were all out, meaning no one was home, but my father wasn’t alarmed. Friday was my mom’s day to go shopping, with my little sister in tow. They usually killed a whole day on the Concourse, going to stores, painting their nails and, depending on what time and what feature was playing, catching a movie at the Paradise and an ice cream at Krum’s. They were usually back around nine o’clock.

My dad tucked me in at eight thirty-five. I awaited my story, but no story came. I had to settle for a kiss on the cheek. He started to leave, but something was bothering me and it just couldn’t wait.

“Dad,” I said, as the door started to close. At first there was nothing, and I feared that my call had come just a little too late.

The door slowly opened. Thank goodness for that. I had information too important to wait. It had to be heard.

“Yes, son?” my dad said.

I fumbled for words. I needed just the right way to express what had been bothering me all the way home. “Um, um.”

“Yes, son, what is it?”

“Well, I just wanted to say that uh, um—”

“Go ahead, Scooter, just let it out.”

So I did as my dad told me—I just let it out. “Dad, I don’t blame Joe.”

“Oh,” said my dad, thinking over my words. “What don’t you blame Joe for?”

“For shaking that dick.”

My sudden confession must have caught him off guard, for he put his hand to his mouth and swallowed real hard. Then he covered his eyes with the hand and rubbed his eyebrows with force, obviously mulling over the depth of my thoughts. Finally he said, “Uh, Scooter, which dick did Joe shake?”

“The one that fucked Marilyn!”

How could he ask? It was so simple. There was only one dick it could possibly be. I looked at my father for some sign of agreement, but he was looking up at the ceiling and shaking his head. Shaking his head like he didn’t agree. I pleaded my case.

“Dad, if that dick fucked my wife, I’d shake him too! Can’t you see? Don’t you—”

My dad cut me off. “Scooter, you’re right. I don’t blame Joe either. Now go to sleep, buddy, okay?”

“Okay, Dad. Good night.”

My dad shut the door and walked down the hall. I heard his footsteps on the stairs as he made his way down to the living room, where he would no doubt ponder my words in the comfort of his rocking chair, with the companionship of a Ballantine beer. I heard the distinctive pop of a tab being pulled. Then a small laugh, then another, and then great gales of laughter that were still at their peak when my mother got home at ten minutes to nine.

From the Hardcover edition.

[ 1 ]

“Dad, what’s a dick?” I was four years old when I let that question loose on my unsuspecting dad, but oddly, I don’t think I’ve given that somewhat strange inquiry a second thought until recently. I’m not sure what seems odder—the ridiculous nature of the question or the fact that my dad never batted an eye upon its delivery. Didn’t bat an eye, didn’t crack a smile, didn’t even turn his head. Instead, he paused, measuring his words, and softly said, “That’s a person who does bad things, son, kind of like a jerk.”

That was the Bronx in 1964, aboard the Third Avenue El train that was only part of a long journey from the northeast corner of the borough to Highbridge, which was just a little northwest of Yankee Stadium, where I lived in a small three-bedroom house on Shakespeare Avenue.

Thirty days earlier, I’d come home from school to find my mother in a state of near shock, my father sitting by her side on our faded red love seat, his shoulder her only visible means of support. My little sister’s slapping soles and happy babbling stood as a stark contrast to the dark aura that hung heavy in our tiny living room.

My father broke the news. My grandfather, a fireman for over thirty years and my roommate for my entire life, had been in an accident. His head, face, chest and arms had been severely burned, and his chances for living were questionable.

I had never been alone before that night. Surrounded by my grandfather, I’d always felt safe. Maybe I should say surrounded by my grandfather and Joe D., for his visage was everywhere. Grinning down at me from every conceivable angle. Following through on his textbook swing as he watched another shot sail out of the seemingly endless confines of Death Valley in left center. His arm around Marilyn, who had played a part in prompting my surprise dick question.

Joe DiMaggio scared me that night. To a young child all alone, he appeared to be glaring, his awkward grin seemed to be taunting me, the gaps in his smile looming large, impossibly large, as if they could inhale a young boy and leave not a trace.

I longed for my grandfather, his soft touch, his smell, his sound. The touch of his thick, calloused fingers tousling my hair. I missed his soft, gentle brogue, an ode to his ancestral homeland, even though his ancestors had left Ireland a century before. An accent like his was not uncommon in Highbridge, a strong Irish enclave, but the brogues, like the Irish, were starting to fade and within a short time, like the Irish themselves, would disappear from its streets.

Grandpa used to say that my father had a map of Ireland on his face. Which, after some confusion, I came to learn meant he had traditional Irish features. Fair hair, rusty blond but not quite red, freckles and green eyes. My map wasn’t quite so detailed. I think I had my mother’s face, dark, almost exotic. The result, I’m told, of Spanish blood passed through my veins some centuries before, on some forgotten branch of my mother’s Irish family tree.

I was never sure of Grandpa’s map. To me he never looked Irish, or of any other ethnic group, for that matter. He was Grandpa, after all, which meant to my young, unknowing eyes he’d always looked just . . . old. He was old, but I missed him.

I missed the Scooter as well. Phil Rizzuto, my namesake, was, from April until fall, like a third roommate. A third roommate who showed up each night around seven and wished happy birthdays to strangers and once in a while mentioned the ball game. An old Philco radio, from which the Scooter’s voice would emerge, sat on a small table by Grandpa’s bed. That night it was silent . . . and I missed the Scooter.

I lay awake thinking about Grandpa. Long after the hour when the crack of the bat and happy birthdays to strangers would usually lull me to sleep, I thought of that man. I used the prayers that I’d learned at Sacred Heart Church. I used them over and over, until I knew they would work. I prayed for all his late-night screams to stop. Those infrequent, mournful cries that had been frightening me for as long as I could remember. Those screams that left him cold, but sweating. I prayed for those burns to all go away. So that Grandpa would be back. Back in our house and back in my room. Where he belonged.

I got out of my bed well before dawn. I turned my head from side to side, studying Joe D.’s various likenesses, hoping he wouldn’t decide to swoop down for the kill. I looked out of my window. First across the street at the three-story brick walk-ups, where during daylight hours mothers rested their elbows on pillows to watch over their kids. I looked to my left down the steep hill that led to P.S. 114. The hill where I’d sat on my grandfather’s lap as he steered the Flexible Flyer. Where my little-boy laughs had come out in great clouds of steam. Where my mother had waited, with her hands on her hips, saying her child was too young to sled down such a steep hill. This winter, she said, she might reconsider. But when this winter came, would Grandpa still be alive?

I grew up thinking that my mom babied me, because she wouldn’t let me have the run of the streets like other kids did. But on that first night without Grandpa, I needed my mother. I needed her warmth, her love, and the scent of Wrigley’s Doublemint Chewing Gum and cigarettes with each breath she let go.

I walked out my door and into the hall that separated my sister Patty’s room from mine. I looked for my sister inside her room, though I knew better. She was nearly three now, but she still slept in a crib in my parents’ room, a subject that for over a year had been a bone of contention between my mom and my dad. A bone, it turned out, that my mom always got. For despite the fact that my father had spent two full weekends of the previous summer wallpapering Patty’s room with a pattern of fairies and field mice, the little girl remained a fixture in my parents’ bedroom.

Weekends were not something that my dad parted with lightly. Weekends meant ball games and ball games meant beer, and my father loved both. Nothing extreme, just a six-pack of Ballantine, the Yankees’ proud sponsor, over the course of nine innings. Then would come dinner, and my father would glow, from both his game and his beer. Back in those days the Yankees didn’t lose often, but I think more than the outcome, the game’s timeless rhythm put him at peace. I always hated for Sundays to end, for I knew that when they did, my dad had to go to work across the river in Harlem, walking a beat from four until midnight.

Sure enough, no sister there. I proceeded with care down the short hall. Still on the lookout for Joe D. I had heard of the way he patrolled center field, how surefire doubles met their end in his glove. How he was so fleet of foot that he never needed to dive.

I opened the door. As quietly as possible with two shaking hands. I heard a head stir.

“Scooter, is that you?”

“Yeah, Mom, it’s me.”

“Are you okay?”

“I’m a little bit scared.”

I could almost hear her smile in the darkness. She said, “I guess you’d better come here.”

I practically dove into her arms, then faded off into sleep as she tickled my back.

“Dad?”

“Yes, son?”

“What does ‘fuck’ mean?”

We were walking down 167th, only a few blocks from home, and we hadn’t talked much since we got off our train. In fact, I think my father had been silent since shedding some light on “dick’s” definition. His reaction, again, was slightly low key, considering the subject.

“That’s when someone does something bad to somebody else. It usually concerns money. Kind of like cheating.”

[ 2 ]

My grandfather couldn’t have visitors for those first thirty days. I guess due to the threat of infection. He’d nearly died that first night. My dad had grown silent and sullen during the course of that month. On a couple of nights I heard beer tabs in the darkness, a prescription for sorrow after a long night of work.

My dad had rejoiced when he’d gotten the phone call. My grandfather’s life was no longer in danger. He’d been transferred to Bronx Psychiatric to undergo testing, but at least he was alive and, better yet, could have guests.

My father woke me up early on the day of our visit. He didn’t smile often, at least not in matters that didn’t concern a ball game. But on this day in question his smile was a wide one.

“Scooter, wake up.”

I blinked once or twice and then turned off Grandpa’s Philco, which I had placed next to my bed a week after he’d left.

“Hi, Dad,” I said.

“Guess who we’re seeing today?”

“Grandpa,” I said, my voice high with excitement.

“You betcha,” he said, then he glanced around my room, allowing his eyes to take in every single shot of Joe D. “Yes, we’re gonna see Grandpa, but we’re gonna see someone else too.”

My dad was so excited that I thought he might cry. Just seeing Grandpa would be the absolute best, but my dad was holding a secret, as if things could somehow get better.

He said, “Go ahead, guess.”

My mind drew a big blank. Once again, my dad’s eyes darted around the room.

I shook my head, clearly puzzled, then said, “I don’t know.”

My dad’s face formed a frown, but it was quickly erased by a grin even bigger than the one I’d awoken to. “I’ll give you a hint—he’s on your wall.”

“Batman!” I yelled. “I’m gonna meet Batman!” I looked over my bed at a picture of TV’s newest sensation that my mom had cut out of the paper and taped to the wall.

“No, Scooter, not Batman.” My dad played it off as if he was amused, but even at the age of four I could hear the disappointment in his voice. This was his moment, and I was in the process of ruining it, all due to Bruce Wayne’s alter ego.

I looked at the walls. Aside from Batman, a faded, yellowed snapshot of a pretty teenage girl and a 1959 photo of my father in the Daily News, the choices were slim. There was a photo of me, in front of the Babe’s monument in the outfield at the stadium, looking just a tad more than terrified, I think due to the fact that I thought the Sultan of Swat was buried right there and that I was posing for photos on top of his grave. After that, there was no one except—

“Joe D.?” I asked, with a level of enthusiasm usually reserved for the discovery of lima beans on one’s dinner plate.

“That’s right. Joe D.,” he said, making up for my lack of excitement by doubling his own. “But it gets even better. Guess where we’re meeting him?”

I had no idea, and told him as much. My answer didn’t faze him. My father was on a roll now, savoring a high that usually came only with a frank and a cold one during our yearly pilgrimage to the stadium, and neither my ignorance nor my apathy was going to slow him down. “Today!—You—and I—are going . . . to . . . Freedomland!”

“Freedomland!?” I yelled.

“Freedomland Indeedomland!” he yelled back.

I temporarily forgot about my poor grandfather, so blinded with excitement was I. Freedomland was like a dream. Farther away from home than I’d ever been. All the way on the other side of the Bronx. I had begged my dad to take me there for as long as I could remember, ever since hearing “Mommy and Daddy, take my hand, take me out to Freedomland” on the radio. Ever since hearing Johnny Horton sing the Freedomland theme song, “Johnny Freedom,” on the jukebox at Rossi’s Sandwich Shop. Today the dream was real. My father seemed to feed off my euphoria, detailing with relish just how our day would proceed.

“We’ll head down to Cozy Corners for a new ball and a coffee. How ’bout an egg cream while we’re at it? Then we’re off for the train to Gun Hill, take the bus to Baychester, and BAM! Before you know it, you’re merry-go-roundin’ in Kandy Kane Lane. Then after you’ve had more fun than one little guy can stand, BAM! We go see Joe D.!”

[ 3 ]

The day went just as my dad had planned. BAM! I rode the merry-go-round in Kandy Kane Lane. I didn’t know then that Freedomland was in its dying days. That I’d never see it again. It didn’t occur to me that 1909 Cadillacs didn’t belong on the Civil War battlefield, or that Elsie the Cow was at the World’s Fair. I only knew that souvenirs were a quarter, and my dad was in the mood to spend. A mood I’d never seen him in before, and would never see again. Sure enough, I had more fun than one little guy could stand, and then, BAM!, we went to see Joe D. with Grandpa’s old Philco tucked underneath my father’s arm.

My dad had told me how he and Grandpa used to wait for hours after games for Joe D. to emerge. Just to see him walk by on his way to the car. Just to say hello, maybe get him to sign a yearbook or a ball. But Joe D. never emerged. My grandfather wondered if the stadium had some secret underground passageway so that Joe D. could escape undetected. Kind of like the secret exit from the Batcave, I guess.

They had never met Joe D., but they sure had met a lot of other guys. Yogi. Larsen. Lopat. Bauer. Mantle too. My father showed me his collection a few times. Two decades of Yankee royalty, their signatures scribbled on a cavalcade of memorabilia—yearbooks, scorecards, ticket stubs, balls, gloves, Spaldeens, even a Krum’s menu. But the crown jewel of my dad’s collection was his photo of the Scooter, 1950, the year he won the MVP, posed with my dad, both of them smiling.

The Scooter had driven in the winning run that day, bunted it in, a suicide squeeze, and when he posed for the picture, he let my dad hold the bat. Then he walked away. He just walked away and let my dad have the bat.

My dad got his bat. I got his name. Why couldn’t Rizzuto have taken DiMaggio’s tunnel on that fateful day?

But on this day, for the first time, my father would see the great Yankee Clipper. Just as soon as he waited in a line several hundred feet long, where die-hard Yankee fans all waited for the greatest living ballplayer to write down his name. All except the guy right in front of us, who had nothing to be signed. Which struck my dad as rather strange.

“Whattaya want Joe to sign?” he asked the guy.

“Nothin’,” the guy said.

“Nothin’?”

“Nah, nothin’.”

My dad hadn’t inherited his father’s brogue, but he didn’t have a typical “Noo Yawk” accent either. Very few people in Highbridge did. I escaped somewhat unscathed as well. Some Bronxites, however, including my mother, didn’t get off quite so lucky. This guy, the “nothin’ ” guy, may have been the unluckiest of all.

My dad didn’t quite know what to make of the guy, who didn’t have a kid with him and didn’t appear to be a connoisseur of amusement park rides. The guy was definitely there to see Joe D., yet had “nothin’ ” to sign. It didn’t make sense.

A few more minutes went by. Joe was in sight now, or at least the green curtain that he was sitting behind was in sight. Apparently, you had to pay to see Joe. There were no free peeks at the Clipper. Even the “nothin’ ” guy had paid his two bucks—it was a shame that he’d leave with “nothin’ ” to show for it.

Curiosity finally got the better of my dad. He didn’t want to ask, but I guess he felt like he had to.

“Whattaya here for if you don’t want Joe to sign?” my father asked.

The guy smiled. Not a friendly smile, just a little corner-of-the-mouth smile. He was a big guy, much bigger than my dad. I thought there might be trouble. After a tense moment, the guy seemed to relax. His smile even became friendly.

“Hey, buddy,” the guy said, “I just wanna shake Joe’s hand.”

The guy and my dad then proceeded to reminisce about great Joe D. moments. Great Joe D. hits, great Joe D. catches. Great Joe D. wives.

Gradually, the curtain got closer. I could see Joe’s silhouette as he wrote down his name, could see the pen performing its elegant arcs, could see the cigarette as he brought it to his lips for a long, refreshing drag. We were next. Yes! We were next! I’d never even seen Joe play, but we were next. His pictures scared the crap out of me, but we were next. I could hear Joe’s voice, rich and resonant, as he spoke to the guy in front of us—the “nothin’ ” guy.

“What would you like me to sign?” the Clipper asked.

“Nothin’.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothin’.”

“Excuse me?”

“Nothin’, I got nothin’ to sign.”

“I’ve got a piece of paper here. I’ll just sign that.”

“No, I don’t want nothin’ signed.”

I could see Joe’s silhouette stiffen. I could see the silhouettes of Joe’s two beefy security guards stiffen too. When Joe spoke, it was with agitation.

“If you don’t want me to sign anything, why are you here?”

I could see the nothin’ guy shrink. Even from a seated position, Joe D. suddenly loomed much larger than life. Much larger than the recipient of Joe’s very well-mannered bile, who now fumbled for words.

The “nothin’ ” guy finally said, “I just wanna shake your hand.”

“You want to shake my hand?” Joe asked, his disbelief mingling with sarcasm.

“Yeah, how ’bout it?” I could see the guy stick his arm out.

A deep voice rang out, very official. “Mr. DiMaggio, would you like me to remove this man?”

“No, that’s okay,” Joe said. He now sounded intrigued, slightly amused. “This gentleman just wants to shake my hand. Isn’t that correct?”

“Yeah, so how ’bout it?” The guy stuck his hand out again.

“Hold on a moment,” Joe said. He was having fun now, toying with the big guy, sitting back and watching him squirm. He was like a fish on Joe’s hook and Joe was going to reel him in, just as he had done in his youth on the docks of San Francisco. It was just too bad that Freedomland’s San Francisco area had closed down. The irony would have been incredible—Joe D. baiting and hooking this poor slob right on Fisherman’s Wharf.

I could see Joe put his arms behind his head. He leaned back and said, “Let me get this straight. You paid two dollars to get into the park. Then you paid two dollars to stand in line. Then, after standing in line for quite a while, you tell me that you just want to shake my hand. Is that correct?”

“Yeah, Joe, that’s right.”

“Why?”

“I got my reasons.”

“I would like to know what those reasons are.”

“No, Joe, I don’t think you do.”

“Yes, as a matter of fact I do.” Joe sat up now. He wasn’t quite as composed. The fish was fighting back. Joe reached for a verbal harpoon. And hurled it. “Sir, either you tell me now or I’ll have you escorted from the park.”

“You really wanna know?”

“Yes.”

“Ya sure?”

“Yes, I’m sure.”

The guy let out a breath of air. Then let Joe have just a little bigger dose of truth than he was prepared to handle.

“I just wanted to shake the hand that shook the dick that fucked Marilyn Monroe.”

The Clipper jumped up and stormed off through a steel door and slammed it shut behind him. I wasn’t sure where it led, an office perhaps, maybe a closet, but I was reasonably sure that things started breaking behind that steel door.

“Dad, why is Joe mad?” I asked.

My dad didn’t say a word.

The big guy who wanted “nothin’ ” signed didn’t look so big as he was being whisked away. He was kind of doubled over, maybe from the punches that Joe’s two security guards directed at his midsection. I hadn’t seen punches thrown in quite a while. My mom didn’t let me watch bad shows on TV, and my dad was under strict orders to get up and switch the channel when one of baseball’s bench-clearing brawls broke out.

Following the “nothin’ ” guy’s departure, Joe D.’s security informed the line that the autograph session was over. Refunds were offered. But my dad didn’t want a refund—he wanted Joe. I watched my father’s face as he contemplated his course of action. Wrinkles on his brow, adding a decade to his twenty-seven years. Biting down on his lower lip, a mannerism that would become increasingly more prevalent in his demeanor as the years went by. His way of fighting off natural instincts of aggression in favor of a cooler head.

“Scooter, stay here for just a second,” he said as he stepped out of a line that was fast dissolving and approached the protective layer of Joe’s men.

My dad put a hand on one man’s broad shoulder. The hand was slapped away. My father tried again. Again his gesture was rebuffed. My dad reached for his pocket. His holster, I thought. My dad’s drawing his gun. I could almost read the headlines. a death at freedomland. But when his hand came out, it didn’t hold a gun. It held a badge instead. A badge that got the guy’s attention and a sympathetic ear for my father’s real-life woe. When my dad returned minutes later, the line was all but gone. Gone except for me, and a somewhat angry fan who was yelling at Joe’s door that Ted Williams should have been MVP back in ’41.

“Joe will see us in a little while,” my father said.

A little while, it turned out, was quite a while. Forty-seven minutes, to be exact. Long enough for me to replay the day’s events in my mind several times. I thought of the egg cream, the train, the bus, the rides. I thought of the big guy who didn’t want nothin’ signed and the sound of things breaking behind the door Joe had slammed. But I kept coming back to the way I had felt when my dad reached for his badge. I had really believed that he was going to spray Freedomland full of lead. And I thought it would have been justified. But pulling a gun was against my dad’s nature. I had heard him explain on many occasions how he intended to put in twenty years on the force without ever firing. It was an intention that had put him at odds right away with his father-in-law, a retired First Grade detective in New York’s Four-O district in Motthaven, a close Bronx neighbor of Highbridge. Apparently, my mother’s father had amassed an impressive arrest and body count during his days on the force, and he had showed very little understanding or respect for my father’s somewhat more humanitarian approach to law enforcement. My dad walked a beat on the mean streets of Harlem, and he did so without fear and with a heartfelt belief that every life was worth helping. I guess a Joe D. tantrum at the fun park was not such a big deal after all.

The security guy put his hand on my dad’s shoulder. “The Dago will see you” was all that he said.

I followed my dad, who had the Philco under his arm, as he made his way to Joe D.’s steel door. I looked at Joe’s curtain as I passed it by and wondered if Grandpa might like a few of Joe’s smoked butts to keep in his room. I thought that he would, but I was too scared to ask.

The heavy door opened, and Joe D. himself looked straight into my eyes. He didn’t look goofy or awkward like he had in ’41, when he’d hit in fifty-six straight. And I was reasonably sure that he wouldn’t inhale me. He just looked sad and lonely, sitting behind an ugly gray desk whose contents lay scattered and broken and battered on the dirty tile floor. There was a hole in the wall that looked newly formed.

Joe D. spoke with a whisper, his voice barely audible as he expressed his regret at what had transpired. Then he expressed his remorse for my grandfather’s health. “I hope this will help,” said the Clipper, as he took the ball from my father and rolled it in the palm of his left hand until he found the sweet spot. When he picked up his pen, I could see his right knuckles were bleeding.

Joe signed his name with the ease of a man who had done such a task thousands of times. As he did, I studied his hands and saw one drop of blood make a long, lonely trip from the wound’s point of origin to the tip of his finger to the point of his pen. Black ink and Joe’s blood became one and the same as he looped his last “o,” and it wasn’t until later, on our short cab ride to Bronx Psychiatric, that the “o” became smudged and the red scarred the white sphere.

[ 4 ]

I wasn’t prepared for what I saw in room 317. The sight of my grandfather lying in bed, his face swathed in gauze, not a trace of skin showing. I wasn’t prepared for the sounds of that place either, distant screams that seemed to pull at my feet, as if trying to drag me through concrete, to unknown horrors below. I wanted to leave, to get out of that place, and I started to tug on my father’s coat sleeve. I loved my grandfather, but this wasn’t him. This man was a monster, a mummy, a ghoul. I tugged the sleeve harder.

My father glanced down, more hurt than annoyed. “Say hello to your grandpa” was all he said. But I couldn’t speak. I just turned away. The thing in the bed couldn’t speak either. Was it even alive?

My dad did the talking. He talked to a ghoul. He talked to an unseeing, unfeeling, unmoving ghoul. The Bronx Bombers in five, the Cardinals couldn’t stack up. Gibson’s heat was no match for Whitey’s best stuff. Flood couldn’t lace the Mick’s shoes in center. He placed the old Philco on a shelf by the bed. Game number one of the ’64 Series began the next day. He thought Grandpa might like to listen. But Grandpa was gone. And the thing in his place wasn’t responding.

My dad’s hands were shaking as he reached for Joe’s ball. His red, swollen eyes were rimmed with welled tears. He looked like he’d aged since we entered the room. His voice shook when he spoke.

“I got somethin’ for you.”

He took out the ball and rewrote the day’s history as he fought back his tears.

“I saw Joe D. today, Dad. Yeah, can you believe it? Me and Scooter saw him. I took Scooter to Freedomland, he had the time of his life. You gotta see the place, Dad. You’d love it, I swear. Scooter helped put out the great fire in Chicago. He wanted to help so he could be just like you. Then, as we’re eatin’ Chinese in San Fran, Scooter tugs on my sleeve. I say, ‘Scooter, hold on, I’m tryin’ to eat.’ But he tugs on my arm, so I look up at your roommate and he’s pointin’ out in the street, over by the Seal Pool. So I look where he’s pointin’ and who do I see? Joe D. ‘Yeah, Joe D.’ I know Joe likes his privacy, but I couldn’t resist, so I walk on over and I say hello and I tell him my father is his number one fan. And I’ll tell you what, Dad, Joe couldn’t have been nicer. He even pulled out a ball and signed it for you. And I got it right here. Isn’t that just how it went, son?”

I’d never once heard my dad tell a lie, let alone ten in a row, but in spite of that fact, I nodded my head. I don’t know why. It’s not like the monster could see me. Or hear one word that my father said. My father held out the ball . . . and the thing moved its hand. At first it moved slowly, hardly at all, but it moved just the same. The hand started to rise. I felt a lump in my throat. My father lowered the ball. The thing’s hand met it halfway. The thing was my grandpa, and he was touching the ball. My dad wrapped Grandpa’s fingers around Joe D.’s smudged ball and, just for a moment, the hand held it there. Then the hand slowly lowered and put the ball to its heart. My knees went weak and I thought I would fall. I leaned on my father’s leg to help me stay up, and he reached down for me and stroked my short hair. I looked up at my dad and there were tears on his face.

[ 5 ]

My father was silent the entire way home, my two poignant questions being the trip’s only exceptions. A few kids were playing stoopball as we approached our little blue house. Darkness was falling and Shakespeare was quiet, almost eerily so. My dad waved to a neighbor, whose day probably hadn’t been quite as hectic as ours. The lights were all out, meaning no one was home, but my father wasn’t alarmed. Friday was my mom’s day to go shopping, with my little sister in tow. They usually killed a whole day on the Concourse, going to stores, painting their nails and, depending on what time and what feature was playing, catching a movie at the Paradise and an ice cream at Krum’s. They were usually back around nine o’clock.

My dad tucked me in at eight thirty-five. I awaited my story, but no story came. I had to settle for a kiss on the cheek. He started to leave, but something was bothering me and it just couldn’t wait.

“Dad,” I said, as the door started to close. At first there was nothing, and I feared that my call had come just a little too late.

The door slowly opened. Thank goodness for that. I had information too important to wait. It had to be heard.

“Yes, son?” my dad said.

I fumbled for words. I needed just the right way to express what had been bothering me all the way home. “Um, um.”

“Yes, son, what is it?”

“Well, I just wanted to say that uh, um—”

“Go ahead, Scooter, just let it out.”

So I did as my dad told me—I just let it out. “Dad, I don’t blame Joe.”

“Oh,” said my dad, thinking over my words. “What don’t you blame Joe for?”

“For shaking that dick.”

My sudden confession must have caught him off guard, for he put his hand to his mouth and swallowed real hard. Then he covered his eyes with the hand and rubbed his eyebrows with force, obviously mulling over the depth of my thoughts. Finally he said, “Uh, Scooter, which dick did Joe shake?”

“The one that fucked Marilyn!”

How could he ask? It was so simple. There was only one dick it could possibly be. I looked at my father for some sign of agreement, but he was looking up at the ceiling and shaking his head. Shaking his head like he didn’t agree. I pleaded my case.

“Dad, if that dick fucked my wife, I’d shake him too! Can’t you see? Don’t you—”

My dad cut me off. “Scooter, you’re right. I don’t blame Joe either. Now go to sleep, buddy, okay?”

“Okay, Dad. Good night.”

My dad shut the door and walked down the hall. I heard his footsteps on the stairs as he made his way down to the living room, where he would no doubt ponder my words in the comfort of his rocking chair, with the companionship of a Ballantine beer. I heard the distinctive pop of a tab being pulled. Then a small laugh, then another, and then great gales of laughter that were still at their peak when my mother got home at ten minutes to nine.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A very entertaining, warmhearted novel. . . . It's carefree and lively and violent, and comes, of course, with a crash course in America's historic pastime." –The Washington Post"A dark coming-of-age tale and an elegy for a neighborhood in decline. . . . Foley . . . balances Scooter's dark side with qualities that make us root for the character, including good humor, compassion, tenderness and cleverness." –Fort Worth Star-Telegram“Wholly touching. . . . It is each character’s energy and the pure essence of baseball that knocks this story out of the park. . . . A truly entertaining look at youth and the lost face of baseball.” –The Free Lance-Star“Read this book. I say this not only because Mick Foley is a fine writer, but also because he can pick me up one-handed and squash my skull like a grape.” –Dave Barry“Boisterous…Vigorous…A steroid-fueled brawl.”—Publisher’s Weekly“Breakneck-paced, witty, laugh-out-loud funny and—surprisingly—addictively entertaining…A strange mix of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye and Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho.”—Paul Goat Allen, Bookpage“A story of unbearable tenderness and brutality, the tenderness serving to make the brutality more shocking.”—Simon Hattenstone, The Guardian (London)“A raw, picaresque coming-of-age story, by turns funny and darkly violent.”—Michael Harrington, Philadelphia Inquirer“Tietam Brown makes you laugh so hard sometimes it makes you cry. Foley’s achievement…is not only the portrayal of his narrator’s maturation under most unpromising situations. It is also the creation of a great character.”—Christian Sheppard, Chicago Tribune“One of the things that made Foley so effective in wrestling was…his flair for the dramatic and shocking, his sense of humor and his knack for pushing certain emotional buttons. Now, he applies those same skills to his first novel.”—Mark E. Hayes, Miami Herald“Foley knows how to spin an intriguing if somewhat off-beat tale…a compulsively readable first novel.”—Jim Coan, Library Journal“A sometimes lurid, sometimes painful book, but one that ultimately trumpets the human spirit. It’s not ‘good, for a wrestler book.’ It’s good, period.”—Scott E. Williams, Galveston County Daily News