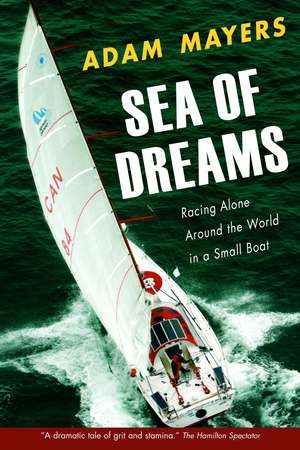

Sea of Dreams: Racing Alone Around the World in a Small Boat

Autor Adam Mayersen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2006

Preț: 95.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 143

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.23€ • 19.79$ • 15.31£

18.23€ • 19.79$ • 15.31£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771057540

ISBN-10: 0771057547

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 162 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771057547

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 162 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

As a journalist with the Toronto Star, Adam Mayers provided comprehensive coverage of the Around Alone race. He is the author of three books.

Extras

IN THE COCKPIT of his boat, Derek Hatfield stood silhouetted in the moonlight of a June night in 2002 on Lake Ontario, his reddish-brown mop of hair and thick policeman’s moustache bristling in profile. He had tucked both hands into the waist of his yellow foul-weather pants to ward off the chill, and plumes of steam rose into the air as he spoke. The air temperature was around freezing. After the warmest winter on record, the upper Great Lakes basin had seen the coldest, wettest spring ever recorded. This had delayed by a month or more the seasonal warming of one of the world’s largest bodies of inland water.

Hatfield’s forty-foot racing sailboat, Spirit of Canada, was sliding down the middle of the lake, the lights of a power plant near Rochester, N.Y., visible to the south and those of the Pickering nuclear plant, east of Toronto, off the stern quarter. Hatfield was talking in measured tones about the epic journey that lay ahead of him. He stood with his legs planted wide, a man of forty-nine, of average height and compact build. Even with the bulky fleece he wore he seemed lean and spare, all sinew and muscle with not an extra ounce of weight. He leaned over and flicked on the autopilot. It whirred and clicked to life, freeing Hatfield to leave the cockpit and walk in sure-footed steps along the length of the fastest, strongest racing sailboat ever built in Canada. She had been assembled by many loving hands, including his own, to withstand the most dangerous natural forces on the planet. Yet she was so supple and swift that she would soon be breaking speed records.

Hatfield touched and tested the rigging as he went, lingering over a turnbuckle here, tugging at a line there, stopping momentarily to listen to the hiss and gurgle of water rushing along the hull. “Am I afraid?” he asked, startled by the question. “Afraid? I’m looking forward to it. I’m concerned about not being able to finish, but that’s not fear. You wouldn’t do this if you were afraid. You couldn’t.”

*****

Many people mess around in boats, but few sail alone and fewer still sail single-handed around the world, which Hatfield was about to do. The paradox is that he dislikes being alone even though he has always liked solitary achievement. At school in Newcastle, New Brunswick, Hatfield eschewed the team play of hockey and football for the individual challenge of track and field and badminton. He savours personal victory and is unafraid of the consequences of defeat.

He came to sailing relatively late, as a married man in his mid-twenties and it took two and a half decades of ever-bigger steps to get to this starry night. He used his day jobs as a fraud-squad Mountie and later on Bay Street to support his growing sailing habit. First, Hatfield crewed aboard a neighbour’s twenty-two-footer from Whitby, Ontario, about twenty-five miles east down the lake from Toronto. His experience was not much different from other novice sailors: the crew bench on Wednesday nights, learning about wind and weather, how a boat moves and why, and the arcane language of luffs and leeches and cleats and clews. He built his own seventeen-footer after reading a few books. A case of “footitis” led to a twenty-five-foot racer/cruiser. A few years later and a few more feet and along came Gizmo, a sleek needle-nosed racing machine in which he crossed the Atlantic Ocean and almost lost his life.

Hatfield is not sure where his love of water came from. His father, Arthur, a retired forester, never sailed, though he built small boats and lovingly helped his son construct Spirit of Canada. Hatfield finds it hard to discuss such emotional things, keeping a cordon sanitaire firmly around his feelings. He is friendly and always polite, but so self-contained and emotionally understated he appears to be passionless. He tries to be inconspicuous and unobtrusive, preferring the sidelines to the limelight, but this stance masks a hunger for adventure and a yearning for dangerous exploits. It explains why he was drawn to a cop’s life and now this, an occupation that has killed far better sailors than he.

Solo sailing is an occupation the French, who are very good at it, call solitaire. It requires a precise mind and level head, two more of Hatfield’s traits. He is not impulsive at all; he is, rather, a very deliberate man. He approaches things methodically, as a task or job to be done. Friends say he sometimes has to work at having fun, even though he can be playful, enjoying jokes and funny stories. But at his core, Hatfield is pragmatic and grounded, stimulated by difficult and involved challenges. He has tremendous patience and stamina, a willingness to work at a task for long hours without rest. He perseveres in the face of difficulty, but knows that, at sea, hardships add up quickly. Sometimes his moods are very dark and he fights feelings of hopelessness when all he wants to do is give up. This will be his hardest personal challenge during this race: maintaining equilibrium and the will to continue.

Hatfield’s world for the next eight months is no bigger than a prison cell, with fewer amenities than those afforded the average killer sentenced to life. He has taken a vow of concentration which means he has no books to read, nor did he bring any music. He sees them as distractions. So there is nothing to read except weather faxes and e-mails and nothing to listen to except the whispering wind and the songs of the sea. There’s no sugar, caffeine, or soft drinks on board. There is no “medicinal” alcohol either as it dulls the senses and numbs the mind. Beneath his veneer of self-confidence, there is a nagging fear of failure, of not being good enough, a concern that he lacks the juice. He worries about the effect of mood swings on his judgment because he knows he will need to stay calm and level in the face of the enormous physical and mental challenges of running the boat alone. His friends have more faith, knowing how much he likes to win, or rather, hates to lose. “If anyone has a chance of finishing, it is Derek Hatfield,” says author Derek Lundy, a friend and admirer. “He’ll do well. Derek has grit and determination. He’s skilled, tough, and determined.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Hatfield’s forty-foot racing sailboat, Spirit of Canada, was sliding down the middle of the lake, the lights of a power plant near Rochester, N.Y., visible to the south and those of the Pickering nuclear plant, east of Toronto, off the stern quarter. Hatfield was talking in measured tones about the epic journey that lay ahead of him. He stood with his legs planted wide, a man of forty-nine, of average height and compact build. Even with the bulky fleece he wore he seemed lean and spare, all sinew and muscle with not an extra ounce of weight. He leaned over and flicked on the autopilot. It whirred and clicked to life, freeing Hatfield to leave the cockpit and walk in sure-footed steps along the length of the fastest, strongest racing sailboat ever built in Canada. She had been assembled by many loving hands, including his own, to withstand the most dangerous natural forces on the planet. Yet she was so supple and swift that she would soon be breaking speed records.

Hatfield touched and tested the rigging as he went, lingering over a turnbuckle here, tugging at a line there, stopping momentarily to listen to the hiss and gurgle of water rushing along the hull. “Am I afraid?” he asked, startled by the question. “Afraid? I’m looking forward to it. I’m concerned about not being able to finish, but that’s not fear. You wouldn’t do this if you were afraid. You couldn’t.”

*****

Many people mess around in boats, but few sail alone and fewer still sail single-handed around the world, which Hatfield was about to do. The paradox is that he dislikes being alone even though he has always liked solitary achievement. At school in Newcastle, New Brunswick, Hatfield eschewed the team play of hockey and football for the individual challenge of track and field and badminton. He savours personal victory and is unafraid of the consequences of defeat.

He came to sailing relatively late, as a married man in his mid-twenties and it took two and a half decades of ever-bigger steps to get to this starry night. He used his day jobs as a fraud-squad Mountie and later on Bay Street to support his growing sailing habit. First, Hatfield crewed aboard a neighbour’s twenty-two-footer from Whitby, Ontario, about twenty-five miles east down the lake from Toronto. His experience was not much different from other novice sailors: the crew bench on Wednesday nights, learning about wind and weather, how a boat moves and why, and the arcane language of luffs and leeches and cleats and clews. He built his own seventeen-footer after reading a few books. A case of “footitis” led to a twenty-five-foot racer/cruiser. A few years later and a few more feet and along came Gizmo, a sleek needle-nosed racing machine in which he crossed the Atlantic Ocean and almost lost his life.

Hatfield is not sure where his love of water came from. His father, Arthur, a retired forester, never sailed, though he built small boats and lovingly helped his son construct Spirit of Canada. Hatfield finds it hard to discuss such emotional things, keeping a cordon sanitaire firmly around his feelings. He is friendly and always polite, but so self-contained and emotionally understated he appears to be passionless. He tries to be inconspicuous and unobtrusive, preferring the sidelines to the limelight, but this stance masks a hunger for adventure and a yearning for dangerous exploits. It explains why he was drawn to a cop’s life and now this, an occupation that has killed far better sailors than he.

Solo sailing is an occupation the French, who are very good at it, call solitaire. It requires a precise mind and level head, two more of Hatfield’s traits. He is not impulsive at all; he is, rather, a very deliberate man. He approaches things methodically, as a task or job to be done. Friends say he sometimes has to work at having fun, even though he can be playful, enjoying jokes and funny stories. But at his core, Hatfield is pragmatic and grounded, stimulated by difficult and involved challenges. He has tremendous patience and stamina, a willingness to work at a task for long hours without rest. He perseveres in the face of difficulty, but knows that, at sea, hardships add up quickly. Sometimes his moods are very dark and he fights feelings of hopelessness when all he wants to do is give up. This will be his hardest personal challenge during this race: maintaining equilibrium and the will to continue.

Hatfield’s world for the next eight months is no bigger than a prison cell, with fewer amenities than those afforded the average killer sentenced to life. He has taken a vow of concentration which means he has no books to read, nor did he bring any music. He sees them as distractions. So there is nothing to read except weather faxes and e-mails and nothing to listen to except the whispering wind and the songs of the sea. There’s no sugar, caffeine, or soft drinks on board. There is no “medicinal” alcohol either as it dulls the senses and numbs the mind. Beneath his veneer of self-confidence, there is a nagging fear of failure, of not being good enough, a concern that he lacks the juice. He worries about the effect of mood swings on his judgment because he knows he will need to stay calm and level in the face of the enormous physical and mental challenges of running the boat alone. His friends have more faith, knowing how much he likes to win, or rather, hates to lose. “If anyone has a chance of finishing, it is Derek Hatfield,” says author Derek Lundy, a friend and admirer. “He’ll do well. Derek has grit and determination. He’s skilled, tough, and determined.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“[A] dramatic tale of grit and stamina.”

— Hamilton Spectator

— Hamilton Spectator