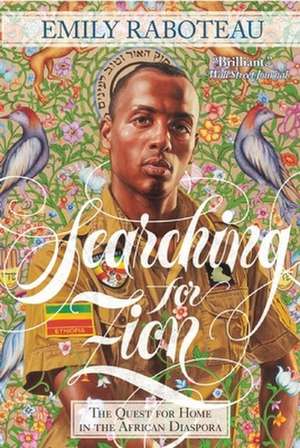

Searching for Zion

Autor Emily Raboteauen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 feb 2014

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Hurston/Wright LEGACY Award (2014)

“A brilliant illustration of the ways in which race is an artificial construct that, like beauty, is often a matter of perspective.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Frank and expansive . . . Each impressionistic, deeply personal vignette is a building block, detailing [Raboteau’s] far-flung search for ‘home’—a ‘promised land’ that’s as brick-and-mortar tangible as it is spiritually confirming.”—Chicago Tribune

A decade in the making, Emily Raboteau’s Searching for Zion takes readers around the world on an unexpected adventure of faith. Both one woman’s quest for a place to call “home” and an investigation into a people’s search for the Promised Land, this landmark work of creative nonfiction is a trenchant inquiry into contemporary and historical ethnic displacement.

At twenty-three, Raboteau traveled to Israel to visit her childhood best friend. While her friend appeared to have found a place to belong, Raboteau couldn’t relate. As a biracial woman from a country still divided along racial lines, she’d never felt at home in America, unable to find her “Zion,” which she defined as a metaphor for freedom. But in Israel, the Jewish Zion, Raboteau was surprised to discover black Jews. Inspired by their exodus, Raboteau sought out other black communities that had left home in search of a Promised Land. Her question for them is the same she asks herself: have you found the home you’re looking for?

On this ten-year journey back in time and across the globe, Raboteau visits Jamaica, Ethiopia, Ghana, and the American South to explore the complex and contradictory perspectives of Black Zionists. She talks to Rastafarians, African Hebrew Israelites, Evangelicals and Ethiopian Jews, and Katrina transplants from her own family, overturning our ideas of place and patriotism, and displacement and dispossession, in a disarmingly honest and refreshingly brave take on the pull of the story of Exodus.

“Frank and expansive . . . Each impressionistic, deeply personal vignette is a building block, detailing [Raboteau’s] far-flung search for ‘home’—a ‘promised land’ that’s as brick-and-mortar tangible as it is spiritually confirming.”—Chicago Tribune

A decade in the making, Emily Raboteau’s Searching for Zion takes readers around the world on an unexpected adventure of faith. Both one woman’s quest for a place to call “home” and an investigation into a people’s search for the Promised Land, this landmark work of creative nonfiction is a trenchant inquiry into contemporary and historical ethnic displacement.

At twenty-three, Raboteau traveled to Israel to visit her childhood best friend. While her friend appeared to have found a place to belong, Raboteau couldn’t relate. As a biracial woman from a country still divided along racial lines, she’d never felt at home in America, unable to find her “Zion,” which she defined as a metaphor for freedom. But in Israel, the Jewish Zion, Raboteau was surprised to discover black Jews. Inspired by their exodus, Raboteau sought out other black communities that had left home in search of a Promised Land. Her question for them is the same she asks herself: have you found the home you’re looking for?

On this ten-year journey back in time and across the globe, Raboteau visits Jamaica, Ethiopia, Ghana, and the American South to explore the complex and contradictory perspectives of Black Zionists. She talks to Rastafarians, African Hebrew Israelites, Evangelicals and Ethiopian Jews, and Katrina transplants from her own family, overturning our ideas of place and patriotism, and displacement and dispossession, in a disarmingly honest and refreshingly brave take on the pull of the story of Exodus.

Preț: 98.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.90€ • 19.73$ • 15.64£

18.90€ • 19.73$ • 15.64£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780802122278

ISBN-10: 0802122272

Pagini: 305

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

ISBN-10: 0802122272

Pagini: 305

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

Recenzii

Winner of a 2014 American Book Award

"Emily Raboteau has written a poignant, passionate, human-scale memoir about the biggest things: identity, faith, and the search for a place to call home in the world. Searching for Zion is as reaching as it is intimate, as original as its old soul. I didn’t want to put this beautiful book down."—Cheryl Strayed

"Lucid and ranging . . . A brilliant illustration of the ways in which race is an artificial construct that, like beauty, is often a matter of perspective."—Thomas Chatterton Williams, The Wall Street Journal

"Brilliant . . . Raboteau's curiosity and keen intellect lead her to find more than she is seeking. . . . [Her] voice is as complex as her journey. Her descriptions are cogent and striking. Her irreverence and gumption provide comic relief."—Imani Perry, San Francisco Chronicle

"This is a beautifully written and thought-provoking book. My head gets blown off every page. Though it describes Raboteau’s very unique journey for her spiritual Zion, it’s somehow wholly universal, too. Everywhere she goes, she hopes to find some straight and golden thread that would draw a line in the direction home, but instead she finds a tangle of humanity that refuses to adhere to any tidy narrative. An African-American named Robert E. Lee who lives in Ghana. Ethiopian Jews who find Jerusalem but not acceptance. And yet everyone she meets she renders with great deftness and empathy—a novelistic level of detail and understanding. I doubt there will be a more important work of nonfiction this year."—Dave Eggers

"Informative, heartfelt . . . The rigor of Raboteau's journalistic work and her candid self-assessment . . . is thoughtful, well-researched, and deeply fascinating."—Kim McLarin, The Washington Post

“An instructive read . . . ‘You don’t stomp on any permanent ground if you’re between black and white,’ Rita Marley, Bob Marley’s widow, tells [Raboteau] in Ghana. ‘You don’t have no grounds as a half-caste.’ But there is a definite arc to Raboteau’s book, and in her way, she proves Rita Marley wrong. She finds the ground she wants to make her own, and she sinks her roots there.”—Laura Collins-Hughes, The Boston Globe

“[Raboteau’s] detailed depictions flash with insight and beauty. A section on slave tourism in Ghana is frankly fascinating, as are the sections on visiting Birmingham, Ala., and Katrina-ravaged New Orleans.”—Lizzie Skurnick, Los Angeles Times

"Extraordinary . . . Beautifully written."—Rebecca Carroll, Good.com

"Vivid . . . Ambitious . . . Frank and expansive."—Lynell George, Chicago Tribune

"An exceptionally beautiful and well researched book about a search for the kind of home for which there is no straight route, the kind of home in which the journey itself is as revelatory as the destination. Go on this timely and poignant journey with Emily Raboteau and you will never think of home in the same way again."—Edwidge Danticat

"I burned through this eye-opening book, utterly engaged with Raboteau’s search—which is, after all, everyone’s search. Raboteau presents a self full of contradictions, smoldering energy, and the willingness to lay it all bare. Searching for Zion is a glorious meditation on what it is to be alive."—Nick Flynn

"Luminous . . . An investigative odyssey . . . With masterful prose and insights bursting from every page."—Judith Basya, Heeb

"No quest for home is ever limited to a simple place, and [Raboteau] evokes that reality beautifully. . . . A fresh perspective [on the] elusive concept of home."—Kirkus Reviews

"Profound and accessible . . . Her earnest, interior study is well worth the journey."—Publishers Weekly

"Part political statement, part memoir, this intense personal account roots the mythic perilous journey in [Raboteau's] search for home. . . . Candid, contemporary . . . Never self-important, this is sure to inspire [a] debate about the search for meaning, whether it concerns 'the din of patriotism' or the lack of closure."—Hazel Rochman, Booklist

"Intelligent and illuminating."—Sharon Chisvin, Winnipeg Free Press

"Emily Raboteau has written a poignant, passionate, human-scale memoir about the biggest things: identity, faith, and the search for a place to call home in the world. Searching for Zion is as reaching as it is intimate, as original as its old soul. I didn’t want to put this beautiful book down."—Cheryl Strayed

"Lucid and ranging . . . A brilliant illustration of the ways in which race is an artificial construct that, like beauty, is often a matter of perspective."—Thomas Chatterton Williams, The Wall Street Journal

"Brilliant . . . Raboteau's curiosity and keen intellect lead her to find more than she is seeking. . . . [Her] voice is as complex as her journey. Her descriptions are cogent and striking. Her irreverence and gumption provide comic relief."—Imani Perry, San Francisco Chronicle

"This is a beautifully written and thought-provoking book. My head gets blown off every page. Though it describes Raboteau’s very unique journey for her spiritual Zion, it’s somehow wholly universal, too. Everywhere she goes, she hopes to find some straight and golden thread that would draw a line in the direction home, but instead she finds a tangle of humanity that refuses to adhere to any tidy narrative. An African-American named Robert E. Lee who lives in Ghana. Ethiopian Jews who find Jerusalem but not acceptance. And yet everyone she meets she renders with great deftness and empathy—a novelistic level of detail and understanding. I doubt there will be a more important work of nonfiction this year."—Dave Eggers

"Informative, heartfelt . . . The rigor of Raboteau's journalistic work and her candid self-assessment . . . is thoughtful, well-researched, and deeply fascinating."—Kim McLarin, The Washington Post

“An instructive read . . . ‘You don’t stomp on any permanent ground if you’re between black and white,’ Rita Marley, Bob Marley’s widow, tells [Raboteau] in Ghana. ‘You don’t have no grounds as a half-caste.’ But there is a definite arc to Raboteau’s book, and in her way, she proves Rita Marley wrong. She finds the ground she wants to make her own, and she sinks her roots there.”—Laura Collins-Hughes, The Boston Globe

“[Raboteau’s] detailed depictions flash with insight and beauty. A section on slave tourism in Ghana is frankly fascinating, as are the sections on visiting Birmingham, Ala., and Katrina-ravaged New Orleans.”—Lizzie Skurnick, Los Angeles Times

"Extraordinary . . . Beautifully written."—Rebecca Carroll, Good.com

"Vivid . . . Ambitious . . . Frank and expansive."—Lynell George, Chicago Tribune

"An exceptionally beautiful and well researched book about a search for the kind of home for which there is no straight route, the kind of home in which the journey itself is as revelatory as the destination. Go on this timely and poignant journey with Emily Raboteau and you will never think of home in the same way again."—Edwidge Danticat

"I burned through this eye-opening book, utterly engaged with Raboteau’s search—which is, after all, everyone’s search. Raboteau presents a self full of contradictions, smoldering energy, and the willingness to lay it all bare. Searching for Zion is a glorious meditation on what it is to be alive."—Nick Flynn

"Luminous . . . An investigative odyssey . . . With masterful prose and insights bursting from every page."—Judith Basya, Heeb

"No quest for home is ever limited to a simple place, and [Raboteau] evokes that reality beautifully. . . . A fresh perspective [on the] elusive concept of home."—Kirkus Reviews

"Profound and accessible . . . Her earnest, interior study is well worth the journey."—Publishers Weekly

"Part political statement, part memoir, this intense personal account roots the mythic perilous journey in [Raboteau's] search for home. . . . Candid, contemporary . . . Never self-important, this is sure to inspire [a] debate about the search for meaning, whether it concerns 'the din of patriotism' or the lack of closure."—Hazel Rochman, Booklist

"Intelligent and illuminating."—Sharon Chisvin, Winnipeg Free Press

Notă biografică

Emily Raboteau is the author of the critically acclaimed novel, The Professor’s Daughter. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Best American Short Stories, Best African American Fiction, The Guardian, Oxford American, Tin House and elsewhere. Recipient of numerous awards including a Pushcart Prize and a Literature Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Raboteau also teaches creative writing at The City College of New York in Harlem.

Extras

ISRAEL: We’re Going to Jerusalem

The security personnel of EL AL Airlines descended on me like a flock of vultures. There were five of them, in uniform, blockading Newark Inernational Airport’s check-in counter. Two women, three men. They looked old enough to have finished their obligatory service in the Israeli Defense Forces but not old enough to have finished college, which meant they were slightly younger than me. I was prepared for the initial question, “What are you?”, which I’ve been asked my entire life, and, though it chafed me, I knew the canned answer that would satisfy: “I look the way I do because my mother is white and my father is black.” This time the usual reply wasn’t good enough. This time the interrogation was tribal. They questioned me rapidly, taking turns.

“What do you mean, black? Where are you from?”

“New Jersey.”

“Why are you going to Israel?”

“To visit a friend.”

“What is your friend?”

“She’s a Cancer.”

“She has cancer?”

“No, no. She’s healthy.”

“She’s Jewish?”

“Yes.”

“How do you know her?”

“We grew up together.”

“Do you speak Hebrew?”

“Shalom,” I began. “Barukh atah Adonai…” I couldn’t remember the rest of the blessing, so I finished with a word I remembered for its perfect onomatopoetic rendering of the sound of liquid being poured from the narrow neck of a vessel: “Bakbuk.”

It means bottle. I must have sounded like a babbling idiot.

“That’s all I know,” I said. I felt ridiculous, but also pissed off at them for making me feel that way. I was twenty-three. I was a kid. I was an angry kid and so were they.

“Where is your father from?”

“Mississippi.”

“No.” By now they were exasperated. “Where are your people from?”

“The United States.”

“Before that. Your ancestors. Where did they come from?”

“My mother’s people are from Ireland.”

They looked doubtful. “What kind of name is this?” They pointed at my opened passport.

I felt cornered and all I had to defend myself with was my big mouth. It was so obviously not a time for joking. “A surname,” I joked.

“How do you say it?”

“Don’t ask me. It’s French.” There was a village in Haiti called Raboteau. That much I knew. Raboteau may once have been a sugar plantation, named for its French owner, one of whose slaves may have been my ancestor. It’s also possible I descended from the master himself. Or from both – master and slave.

“You’re French?” they pressed.

“No, I told you. I’m American.”

“This!” They stabbed at my middle name, Ishem. “What is the meaning of this name?”

“I don’t know,” I answered, honestly. I was named after my father’s great-aunt, Emily Ishem, who died of cancer long before I was born. I had little idea where the name came from, just a vague sense that like many slave names, it was European. My father couldn’t name anyone from our family tree before his great-grandmother, Mary Lloyd, a slave from New Orleans. Preceding her was a terrible blank. After Mary Lloyd came Edward Ishem, the son she named after his white father, a merchant marine who threatened to take the boy back with him to Europe. To save him, Mary shepherded her son to the Bay of St. Louis where it empties into the Mississippi Sound. There he grew up and married a Creole woman called, deliciously, Philomena Laneaux. They gave birth to my grandmother, Mabel Sincere, and her favorite sister, Emily Ishem, for whom I am named.

“It sounds Arabic,” one of them remarked.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Do you speak Arabic?”

“I know better than to try.”

“What do you mean?”

“No, I don’t speak Arabic.”

“What are your origins?”

I felt caught in a loop of the Abbot and Costello routine, “Who’s on first?” There was no place for me inside their rhetoric. I didn’t have the right vocabulary. I didn’t have the right pedigree. My mixed race had made me a perpetual unanswered question. The Atlantic slave trade had made me a mongrel and a threat.

“Ms. Raboteau! Do you want to get on that plane?”

I was beginning to wonder.

“Do you?”

“Yes.”

“Answer the question then! What are your origins?”

What else was I supposed to say?

“A sperm and an egg,” I snapped.

That’s when they grabbed my luggage, whisked me to the basement, stripped off my clothes and probed every inch of my body for explosives, inside and out. When they didn’t find any, they focused on my tattoo, a Japanese character. According to the tattoo artist it meant different, precious, unique.

I was completely naked, and the room was cold. My nipples were hard. I tried to cover myself with my hands. I remember feeling incredibly thirsty. One of them flicked my left shoulder with a latex glove. “What does it mean?” he asked. This was the first time I’d been racially profiled, not that the experience would have been any less humiliating had it been my five hundredth. “It means Fuck You,” I wanted to say, not merely because they’d stripped me of my dignity, but because they’d shoved my face into my own rootlessness. I have never felt more black in my life than I did when I was mistaken for an Arab.

***

Why was I so angry? As a consequence of growing up half white in a nation divided along racial lines, I had never felt at home in the United States. Being half black, I identified with James Baldwin’s line in The Fire Next Time about black GIs returning from war only to discover the democracy they’d risked their lives to defend abroad continued to elude them at home: “Home! The very word begins to have a despairing and diabolical ring.” Though my successful father, Princeton University’s Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion, was an exception to the rule that black people had fewer opportunities, and though I had advantages up the wazoo, I remained so disillusioned about American equality that much of my young adulthood was spent in a blanket of low-burning rage.

I inherited my sense of displacement from my father. It had something to do with the legacy of our slave past. Our ancestors did not come to this country freely, but by force – the general Kunta Kinte rap of the uprooted. But it had even more to do with the particular circumstances of my grandfather’s death. He was murdered in the state of Mississippi in 1943. Afterwards, my grandmother, Mabel, fled North with her children, in search, like so many blacks who left the South, of the Promised Land. It was as if my father, whose father had been ripped from him, had been exiled. My father’s feelings of homelessness, which I took on, were therefore historical and personal. And truthfully, because he left my family when I was sixteen, my estrangement had also to do with the loss of him. My family was broken, and outside of its context, I didn’t belong. The EL AL security staff had turned up the flame beneath these feelings. At twenty-three I hadn’t seen much of the world. I hadn’t yet traveled beyond the borders in my own head.

But now I was boarding a plane to visit my best friend from childhood, Tamar Cohen. With Tamar, I had a home. We loved each other with the fierce infatuation of preadolescent girls—a love that found its form in bike rides along the tow-path, notes written in lemon juice, and pantomimed tea parties at the bottoms of swimming pools. The years we spent growing up in the privileged, picturesque, and predominantly white town of Princeton, New Jersey, where both of our fathers were professors of religious history, were marked by a sense of being different. Tamar’s otherness was cultural: her summers were spent in Israel, her Saturdays at synagogue, and, up until the seventh grade, she attended a yeshiva. I was black. Well, I was blackish in a land where one is expected to be one thing or the other. That was enough to set me apart. I didn’t fit. I looked different from the white kids, though not exactly black.

My otherness was cultural too. I played with black dolls, listened to black music, and, thanks to my parents if not my school, learned black history.

Being different allowed Tamar and me to hold everyone else in slight disdain, especially if they happened to play field hockey or football. We were a unified front against conformity. We stood next to each other in the soprano section of the Princeton High School Choir like two petite soldiers in our matching navy blue robes, sharing a folder of sheet music with a synchronicity of spirit that could trick a listener into believing that we possessed a single voice. When I received my confirmation in Christ, I borrowed Tamar’s bat mitzvah dress.

We were bookish girls, intense and watchful. We spent afternoons sprawled out on my living room rug doing algebra homework while listening to my dad’s old Bob Marley records – Soul Rebel, Catch a Fire, and our favorite, Exodus. Our Friday nights were spent eating Shabbat dinner at her house around the corner on Murray Place. I felt proud being able to recite the Hebrew blessing with her family after the sun went down and the candles were lit: “Barukh atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha’olam…” Blessed are You, Lord, our God, sovereign of the universe…I didn’t actually comprehend the words at the time, but I believed the solemn ritual made me part of something ancient and large.

Perhaps stemming from that belief, much to my father’s chagrin, I started to keep kosher, daintily picking the shrimp and crab legs out of his Mississippi jambalaya until all that remained on my plate was a muck of soupy rice. It was her father’s turn to be upset when we turned eighteen and got matching tattoos on our left shoulder blades. The Torah forbids tattooing (Leviticus 19:28). Tamar’s might someday disqualify her from burial in a Jewish cemetery but we were determined that, no matter where in the world we might end up, no matter how much time might pass, even when we were old and ugly and gray, we would always be able to recognize each other.

Tamar’s father was an expert in medieval Jewish history, while mine specialized in antebellum African-American Christianity. Both men made careers of retrieving and reconstructing the rich histories of ingloriously interrupted peoples. Tamar and I knew at a relatively young age what the word diaspora meant—though to this day that word makes me visualize a diaspore, the white Afro-puff of a dandelion being blown by my lips into a series of wishes across our old backyard: to be known, to be loved, to belong. Our fathers were quietly angry men, and Tamar and I were sensitive to their anger and its roots. I was acutely aware of that grandfather I had lost to a racially motivated hate crime under Jim Crow, though my father didn’t discuss the murder with me. He didn’t need to give words to my grandfather’s absence anymore than Tamar’s father had to give words to the Holocaust. We weren’t raised on diets of victimhood. But there were powerful ghosts in both our houses.

The security personnel of EL AL Airlines descended on me like a flock of vultures. There were five of them, in uniform, blockading Newark Inernational Airport’s check-in counter. Two women, three men. They looked old enough to have finished their obligatory service in the Israeli Defense Forces but not old enough to have finished college, which meant they were slightly younger than me. I was prepared for the initial question, “What are you?”, which I’ve been asked my entire life, and, though it chafed me, I knew the canned answer that would satisfy: “I look the way I do because my mother is white and my father is black.” This time the usual reply wasn’t good enough. This time the interrogation was tribal. They questioned me rapidly, taking turns.

“What do you mean, black? Where are you from?”

“New Jersey.”

“Why are you going to Israel?”

“To visit a friend.”

“What is your friend?”

“She’s a Cancer.”

“She has cancer?”

“No, no. She’s healthy.”

“She’s Jewish?”

“Yes.”

“How do you know her?”

“We grew up together.”

“Do you speak Hebrew?”

“Shalom,” I began. “Barukh atah Adonai…” I couldn’t remember the rest of the blessing, so I finished with a word I remembered for its perfect onomatopoetic rendering of the sound of liquid being poured from the narrow neck of a vessel: “Bakbuk.”

It means bottle. I must have sounded like a babbling idiot.

“That’s all I know,” I said. I felt ridiculous, but also pissed off at them for making me feel that way. I was twenty-three. I was a kid. I was an angry kid and so were they.

“Where is your father from?”

“Mississippi.”

“No.” By now they were exasperated. “Where are your people from?”

“The United States.”

“Before that. Your ancestors. Where did they come from?”

“My mother’s people are from Ireland.”

They looked doubtful. “What kind of name is this?” They pointed at my opened passport.

I felt cornered and all I had to defend myself with was my big mouth. It was so obviously not a time for joking. “A surname,” I joked.

“How do you say it?”

“Don’t ask me. It’s French.” There was a village in Haiti called Raboteau. That much I knew. Raboteau may once have been a sugar plantation, named for its French owner, one of whose slaves may have been my ancestor. It’s also possible I descended from the master himself. Or from both – master and slave.

“You’re French?” they pressed.

“No, I told you. I’m American.”

“This!” They stabbed at my middle name, Ishem. “What is the meaning of this name?”

“I don’t know,” I answered, honestly. I was named after my father’s great-aunt, Emily Ishem, who died of cancer long before I was born. I had little idea where the name came from, just a vague sense that like many slave names, it was European. My father couldn’t name anyone from our family tree before his great-grandmother, Mary Lloyd, a slave from New Orleans. Preceding her was a terrible blank. After Mary Lloyd came Edward Ishem, the son she named after his white father, a merchant marine who threatened to take the boy back with him to Europe. To save him, Mary shepherded her son to the Bay of St. Louis where it empties into the Mississippi Sound. There he grew up and married a Creole woman called, deliciously, Philomena Laneaux. They gave birth to my grandmother, Mabel Sincere, and her favorite sister, Emily Ishem, for whom I am named.

“It sounds Arabic,” one of them remarked.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Do you speak Arabic?”

“I know better than to try.”

“What do you mean?”

“No, I don’t speak Arabic.”

“What are your origins?”

I felt caught in a loop of the Abbot and Costello routine, “Who’s on first?” There was no place for me inside their rhetoric. I didn’t have the right vocabulary. I didn’t have the right pedigree. My mixed race had made me a perpetual unanswered question. The Atlantic slave trade had made me a mongrel and a threat.

“Ms. Raboteau! Do you want to get on that plane?”

I was beginning to wonder.

“Do you?”

“Yes.”

“Answer the question then! What are your origins?”

What else was I supposed to say?

“A sperm and an egg,” I snapped.

That’s when they grabbed my luggage, whisked me to the basement, stripped off my clothes and probed every inch of my body for explosives, inside and out. When they didn’t find any, they focused on my tattoo, a Japanese character. According to the tattoo artist it meant different, precious, unique.

I was completely naked, and the room was cold. My nipples were hard. I tried to cover myself with my hands. I remember feeling incredibly thirsty. One of them flicked my left shoulder with a latex glove. “What does it mean?” he asked. This was the first time I’d been racially profiled, not that the experience would have been any less humiliating had it been my five hundredth. “It means Fuck You,” I wanted to say, not merely because they’d stripped me of my dignity, but because they’d shoved my face into my own rootlessness. I have never felt more black in my life than I did when I was mistaken for an Arab.

***

Why was I so angry? As a consequence of growing up half white in a nation divided along racial lines, I had never felt at home in the United States. Being half black, I identified with James Baldwin’s line in The Fire Next Time about black GIs returning from war only to discover the democracy they’d risked their lives to defend abroad continued to elude them at home: “Home! The very word begins to have a despairing and diabolical ring.” Though my successful father, Princeton University’s Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion, was an exception to the rule that black people had fewer opportunities, and though I had advantages up the wazoo, I remained so disillusioned about American equality that much of my young adulthood was spent in a blanket of low-burning rage.

I inherited my sense of displacement from my father. It had something to do with the legacy of our slave past. Our ancestors did not come to this country freely, but by force – the general Kunta Kinte rap of the uprooted. But it had even more to do with the particular circumstances of my grandfather’s death. He was murdered in the state of Mississippi in 1943. Afterwards, my grandmother, Mabel, fled North with her children, in search, like so many blacks who left the South, of the Promised Land. It was as if my father, whose father had been ripped from him, had been exiled. My father’s feelings of homelessness, which I took on, were therefore historical and personal. And truthfully, because he left my family when I was sixteen, my estrangement had also to do with the loss of him. My family was broken, and outside of its context, I didn’t belong. The EL AL security staff had turned up the flame beneath these feelings. At twenty-three I hadn’t seen much of the world. I hadn’t yet traveled beyond the borders in my own head.

But now I was boarding a plane to visit my best friend from childhood, Tamar Cohen. With Tamar, I had a home. We loved each other with the fierce infatuation of preadolescent girls—a love that found its form in bike rides along the tow-path, notes written in lemon juice, and pantomimed tea parties at the bottoms of swimming pools. The years we spent growing up in the privileged, picturesque, and predominantly white town of Princeton, New Jersey, where both of our fathers were professors of religious history, were marked by a sense of being different. Tamar’s otherness was cultural: her summers were spent in Israel, her Saturdays at synagogue, and, up until the seventh grade, she attended a yeshiva. I was black. Well, I was blackish in a land where one is expected to be one thing or the other. That was enough to set me apart. I didn’t fit. I looked different from the white kids, though not exactly black.

My otherness was cultural too. I played with black dolls, listened to black music, and, thanks to my parents if not my school, learned black history.

Being different allowed Tamar and me to hold everyone else in slight disdain, especially if they happened to play field hockey or football. We were a unified front against conformity. We stood next to each other in the soprano section of the Princeton High School Choir like two petite soldiers in our matching navy blue robes, sharing a folder of sheet music with a synchronicity of spirit that could trick a listener into believing that we possessed a single voice. When I received my confirmation in Christ, I borrowed Tamar’s bat mitzvah dress.

We were bookish girls, intense and watchful. We spent afternoons sprawled out on my living room rug doing algebra homework while listening to my dad’s old Bob Marley records – Soul Rebel, Catch a Fire, and our favorite, Exodus. Our Friday nights were spent eating Shabbat dinner at her house around the corner on Murray Place. I felt proud being able to recite the Hebrew blessing with her family after the sun went down and the candles were lit: “Barukh atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha’olam…” Blessed are You, Lord, our God, sovereign of the universe…I didn’t actually comprehend the words at the time, but I believed the solemn ritual made me part of something ancient and large.

Perhaps stemming from that belief, much to my father’s chagrin, I started to keep kosher, daintily picking the shrimp and crab legs out of his Mississippi jambalaya until all that remained on my plate was a muck of soupy rice. It was her father’s turn to be upset when we turned eighteen and got matching tattoos on our left shoulder blades. The Torah forbids tattooing (Leviticus 19:28). Tamar’s might someday disqualify her from burial in a Jewish cemetery but we were determined that, no matter where in the world we might end up, no matter how much time might pass, even when we were old and ugly and gray, we would always be able to recognize each other.

Tamar’s father was an expert in medieval Jewish history, while mine specialized in antebellum African-American Christianity. Both men made careers of retrieving and reconstructing the rich histories of ingloriously interrupted peoples. Tamar and I knew at a relatively young age what the word diaspora meant—though to this day that word makes me visualize a diaspore, the white Afro-puff of a dandelion being blown by my lips into a series of wishes across our old backyard: to be known, to be loved, to belong. Our fathers were quietly angry men, and Tamar and I were sensitive to their anger and its roots. I was acutely aware of that grandfather I had lost to a racially motivated hate crime under Jim Crow, though my father didn’t discuss the murder with me. He didn’t need to give words to my grandfather’s absence anymore than Tamar’s father had to give words to the Holocaust. We weren’t raised on diets of victimhood. But there were powerful ghosts in both our houses.

Premii

- Hurston/Wright LEGACY Award Nominee, 2014