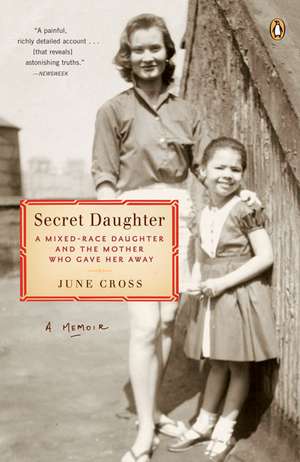

Secret Daughter: A Mixed-Race Daughter and the Mother Who Gave Her Away

Autor June Crossen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2007 – vârsta de la 18 ani

June Cross was born in 1954 to Norma Booth, a glamorous, aspiring white actress, and James “Stump” Cross, a well-known black comedian. Sent by her mother to be raised by black friends when she was four years old and could no longer pass as white, June was plunged into the pain and confusion of a family divided by race. Secret Daughter tells her story of survival. It traces June’s astonishing discoveries about her mother and about her own fierce determination to thrive. This is an inspiring testimony to the endurance of love between mother and daughter, a child and her adoptive parents, and the power of community.

Preț: 135.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 203

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.92€ • 27.06$ • 21.40£

25.92€ • 27.06$ • 21.40£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780143112112

ISBN-10: 0143112112

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: Two 8-page b/w photo inserts

Dimensiuni: 148 x 220 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Penguin Group(CA)

ISBN-10: 0143112112

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: Two 8-page b/w photo inserts

Dimensiuni: 148 x 220 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Penguin Group(CA)

Recenzii

A painful, richly detailed account . . . [that reveals] astonishing truths. (Newsweek)

Searing, revelatory à mind-boggling in its rich and complex interplay of personalities [and] social and racial pressures. (Elle)

Searing, revelatory à mind-boggling in its rich and complex interplay of personalities [and] social and racial pressures. (Elle)

Notă biografică

June Cross is assistant professor of journalism at Columbia University. She has been a television producer for Frontline and the CBS Evening News and was a reporter, producer, and correspondent for PBS's MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.

Extras

Chapter 1

I search for my mother's face in the mirror and see a stranger. Her face is toffee-colored and round; her eyes, the eyes of a foreigner, slanted and brown. They are not my mother's eyes: irises of brilliant green, set obliquely in almond-shaped sockets above high cheekbones.

They said I looked exotic, she classic. Together-a bamboo-colored redhead carrying her olive-sinned, curly-haired toddler-together, we seemed alien. Skin fractured our kinship.

When I was young, riding in the supermarket cart's basket, strangers looked from me to her and back again.

"She's so cute! Is she yours?" they'd ask.

"Yes, she's mine," Mommie would answer before turning the basket in another direction. Looking behind her, sometimes I saw their faces turn sour. I learned to recognize the expression well before I knew what it meant.

At night, before she put me to bed, Mommie and I would find our likenesses. She would ask, 'Who's got a perfect little forehead?"

I'd point above my brows.

"You do!" She'd say with a nod. 'Who's got a perfect little nose?"

"I do!" I'd say, and she would agree again.

"Who's got perfect little hands?"

"We do!"

We laughed over this, our shared proportions: our hands shaped alike-the pinkie exactly half the length of the ring finger, the index and ring fingers each a half inch shorter than the second digit, our nails shaped the same. Even the arches of our feet arced in the same curve, and our toes, too, had a similar square outline.

My mother was an aspiring actress. We lived in the orbit of show business and its backstage shenanigans, where races mixed out of sight of the public. She had separated from my father, a well-known song-and-dance man, shortly after I was born, in January 1954, six months before the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision desegregated the country's schools.

By the time I was three, Negroes in Montgomery, Alabama, had forced the city to integrate its city buses. In Manhattan the buses were already integrated, but an immutable social line nevertheless divided the races, even in the Upper West Side building where Mommie and I lived. African Americans worked there as elevator men but could not rent apartments. The civil-rights movement had not made a dent in our social sphere.

"She looks Chinese," acquaintances guessed, considering the fold of my eyes, the pale olive cast of my skin, my full lips. Oriental-looking, said the middle-aged woman who took care of me much of the time, whom I would come to call "Aunt Peggy."

Aunt Peggy was trying to soothe my feelings-"Oriental-looking Negro women were considered pretty back then-but I knew I wasn't Oriental. Wrapped in a bright yellow towel after my bath, I contemplated the women in the framed Gauguin prints on our walls: their seal-slick black manes, their knowing smiles. Even as a toddler, I somehow grasped that these women would not have considered me Oriental. My mother liked to call me "Tahitian June," but if I were really Tahitian, why wasn't my hair waist long like theirs?

My skin had not yet fully darkened, and my mother lived in fear that we would be found out.

'She'd pass if it weren't for her hair," I overheard Mommie say one day, and my heart collapsed. I didn't know what she meant by that word 'pass" but the tone in her voice sounded the way the faces of the people in the supermarket looked.

I went to the bathroom, climbed atop the toilet seat, and leaned over the sink to explore my short, soft, frizzy curls in the mirror.

My mother's hair fell over her eyes in a bouncy auburn flip that flirted with the world. My hair didn't flip. My curls, soft when they were less than an inch long, frizzed straight out if they grew longer. Mommie made sure they didn't get that long. Cute, Aunt Peggy called my boyish cut. Unusual for a girl, she'd say as she smoothed her own wavy black hair into a French twist. She looked at me in a half-cocked way that meant she didn't really think it was cute, but odd.

In front of the mirror, I tried to pull my hair back with my mother's tortoiseshell comb. The fragile teeth snapped, tangling like splintered tears in my curls.

As far back as I could remember, Mommie traveled. When I was a baby, she took me with her on the plane: by the age of two, I had traveled to Detroit, Las Vegas, and Chicago-I had baby-sized spoons and forks and souvenirs. Once I was able to walk, she would announce she had an audition for an acting job or modeling assignment and, before going, take me to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where she left me with Aunt Peggy and her husband, Uncle Paul.

"I'm visiting Atlantic City, but I really live in New York," I would tell everyone, with my native New Yorker's air of superiority. Moving back and forth between the small seaside town and the big concrete city, I would compare everything, and everything seemed to lead me back to the contours of my face. My mother's lips were primly thin-she wore the stoic expression of a pilgrim. My mouth was broad; my full lips framed a toothy smile. 'You have your father's mouth," Aunt Peggy said when I asked her why I didn't look like Mommie. She told me not to smile so broadly-it showed my gums to my disadvantage.

Then I would kneel on a chair in the dining room, balancing my left arm on the credenza against the wall, and look in the large wall mirror. I practiced curbing my smile. Sometimes I made faces at myself and laughed.

"If Norma doesn't want anybody to know who she is, she better not laugh," Paul commented to Peggy one day in his gravelly voice.

"That laugh belongs to nobody but Norma."

Norma was my mother's first name. I wondered how my mother's laugh could come from my mouth, which was more like my father's. It had been so long since I'd seen my father that I no longer remembered him. I wondered why my mother didn't want anyone to know who I was. Peggy and Paul seemed to understand the answers to these questions, but when I asked, they would look aside and say offhandedly, 'Oh, you'll learn when you're older."

Back in New York, Mommie didn't treat me like a child. When I asked her why my mouth wasn't shaped like her, she paused barely a second before answering, "Well, that's because you're around me all the time, and we spend so much time together." Her explanation made it seem as natural as the fact that we shared square toes.

She began teaching me how to read tones of voice and hear intent, even when it seemed at odds with what she said. We would often spend the afternoon at the movies, sometimes catching the same movie several days' running, and afterward she explained how actors used their bodies to convey character: the way Loretta Young swept down a flight of stairs like an aristocrat, how Gloria Swanson's Staircase descent at the end of Sunset Boulevard made her seem crazy or Katharine Hepburn's in The Philadelphia Story made her seem like she didn't care about losing her boyfriend, when she really cared a lot. Sunset Boulevard was Mommie's favorite movie; Gigi, with Leslie Caron and Maurice Chevalier, became mine. Although I didn't understand the plots of these movies, Mommie had a talent for choosing the one scene that even a four-year-old could grasp, and at home I played my mother's co-star as we reenacted them.

My mother told me stories about her life that seemed as fantastic as any movie star's. She told me she was part Indian, the granddaughter of an outlaw who had ridden with Jesse James's gang. She said she had studied acting with Marlon Brando. She said she has been an Olympic swimmer.

When she told me that her grandpa had performed tricks on horses for Ringling brothers' circus, I thought she was inventing tales; but that one would turn out, like all her stories, to have a strand of truth.

As a young woman, when telling people the story of my life, I chose my words carefully: "My mother didn't raise me. I was raised in Atlantic City, new jersey."

Sometimes I'd add, 'I was raised by my father's people"-"father's people" being a deliberately vague description that could mean my father's brother and sister, some cousins, or, more generally, the entire dark-hued nation. Depending on the race of the listener and how complicated I wished to make the tale, I described those who raised me as my father's sister, my godmother, or my guardians. Aunt Peggy, who after all was not really my aunt but the guardian in question, preferred the last, but my tongue always stuck on that word-"guardian"-it made me feel like a character in a Dickens novel.

In the vernacular of black America, I was 'taken in," or informally adopted.

My mother and I never talked about her decision, how it affected her, the way she saw me and those who looked like me, or how it affected the way I viewed her and those who looked like her. We tried, several times, but it was too painful. She could not look at me-with my wild Afro, wide hips, and Harlem address-and ignore her Upper West Side apartment with the wraparound balcony, her closets full of designer clothes, or her support for Ronald Reagan.

Still, we tried.

"I don't see you as a black woman when I look at you," she protested, almost making me believe her. 'I see you as mine, all mine. I don't see Jimmy in you at all."

Jimmy. That was my father, James Cross.

During the thirties and forties, he had made his fame as a comic who danced in a duo called Stump and Stumpy (Jimmy was known as 'Big Stump," although he was barely five-eight). Stump and Stumpy were headlines then, during the height of the Jazz Age, playing houses like the Cotton Cub and the Paramount Theater, places where blacks could dance onstage but couldn't sit in the audience. When television replaced variety shows in the early fifties, my father's career began a slow nosedive.

My mother had met him backstage at the Paramount in 1949, before television changed the show business forever. She saw a talented comic at the height of his powers, and he saw what he later remembered as the most beautiful woman he had ever laid eyes on. They began a relationship that lasted for five years.

Aunt Peggy liked to say that she had been the landlord of the apartment where I was conceived, as though she were the biblical Sarah and my mother were some kind of Hagar, but as I figure the dates, my mother was already three months pregnant when she and Jimmy moved into a one-bedroom apartment at 407 North Indiana Avenue, where Peggy, an elementary-school teacher, and Paul, a county clerk, owned a house.

Jimmy had been appearing at Club Harlem, the premier black nightclub in Atlantic City, for the summer season, and Mommie and Peggy became friendly. After my parents moved out, and as their relationship went downhill, Mommie began leaving me with Peggy and Paul. These visits got longer and longer, the tell me, until the summer before I started school, she left me there for good.

That year and the four or five that followed were erased from my memory for a long time. When I asked how I came to live in Atlantic City, Aunt Peggy and Mommie stuck to the same story-they said it had been done gradually, so that I would never know what was going on.

But even at four, I knew that something was amiss. I remember the subtle shift of moving from Mommie's world to Aunt Peggy and Uncle Paul's-from what seemed like an unfettered childhood, where I felt treated as an adult and was at the center of attention to a house where children obeyed rules and learned responsibilities. In Atlantic City adults no longer included me in their conversation. If they asked what I thought, it was in a tone reserved for babies. Aunt Peggy and Uncle Paul would sometimes drop their voices low and when I entered the room, looking at me with studied nonchalance and frozen smiles when I asked what they were talking about.

The hardest thing was adjusting to the food.

Mommie cooked simply-grilled meat and a steamed vegetable was our usual fare, while Aunt Peggy's food was heavier and spicy. One night she fixed pork chops with string beans for dinner. The meat was overcooked, the flavoring strange, the string beans a pile of mush accompanying a quarter of the plate. Mommie has always said I had to taste everything and show manners when I was a guest. I managed to swallow the meat, but refused the string beans.

Uncle Paul, his voice cracked by emphysema, ordered me to eat my string beans in his Billy Goat Gruff tone.

I refused.

He insisted, and I refused instantly. Aunt Peggy tries to intervene, joking that Uncle Paul has been a corporal in the army and sometimes it seemed he had never left. He cut his hazel eyes at her, warning her to stay out of this. Then he looked at me.

"You're not leaving this table until you eat your vegetables," he declared.

"I won't and you can't make me!" I shot back.

The battles lines had been drawn. They wouldn't let me leave, but I could make dinner unpleasant for them. I scraped the string beans from one side of the plate to the other with my fork while kicking the table underneath with my heavy oxford shoes.

Finally I was sent upstairs, to my room above the kitchen. Mommie had never made me eat food I didn't want. She would never have banished me from the dinner table. I stomped on the gray linoleum floor, knowing the noise would interrupt Peggy and Paul's dinner.

I heard murmuring below-Paul wanted to come upstairs, but Peggy was telling him firmly to let me get it out of my system. I would show them. I dragged my desk chair to the top of the stairs and pushed it down. It rattled down the steps with such a ruckus that it startled even me, but when no one came, I picked up the little pink stool from the night table and sent it down to. Then all my dolls. And then my books.

A nice-nice heap was growing at the front door of the stairs when the phone rang. I could tell from Aunt Peggy's voice after she answered that it was my mother. I redoubled my efforts then, screaming and crying as loud as I could.

After a while, Aunt Peggy called me to the phone. I pounded down the stairs, grunting and sobbing as I stepped over the pile of furniture on the landing, drooling, my eyes nearly swollen shut from my crying. Taking the phone from Peggy, I poured out the whole story to Mommie. I thought surely she would come on the next bus and save me from these mean people and their nasty food.

Instead she just listened and then quietly said, "You must do as Peggy tells you."

I protested, but she repeated herself and she told me to go, immediately, and apologize to Paul. Her quiet voice carried more authority than all of his haranguing. I hung up the phone and did as she said.

Then Aunt Peggy made me carry everything up the stairs.

In Aunt Peggy's house, I spent hours on my rocking horse, Harry.

Harry had been a present to me from my mother's then boyfriend, an Italian janitor from the Bronx. I had named him after the singer Harry Belafonte, whose 1956 Calypso album had just become the first album to sell over a million copies. "Day-O" was one of my favorite songs, not least for its refrain, "Daylight comes and me wan' go home."

Peggy and Paul had placed Harry opposite the big upholstered chair where Peggy liked to sit while chatting on the phone. I would Pat Harry's neck the way I'd seen the Lone Ranger pat his horse, Silver, on TV, and Harry would come alive. When I spurred his hide, his hollow body answered with a sound as big as the echo across a valley. Away we'd ride, Susannah of the Mounties and Harry, traveling through the Western Territories.

I imagine that I was a girlish Barbara Stanwyck, chasing the bad guys through the crags and gullies in the northern Rocky Mountains. Mother had left me to tend the ranch by myself for a couple of days while she helped the army scout Indians down In Georgia.

Peggy and Paul would watch as I rocked back and forth, oblivious to my surroundings. Once Paul looked at Peggy nervously. "Hey you think she's all right?" he asked. He said "all right" in the tone you use when you are wondering if someone's cuckoo.

When I was a teenager, Peggy told me this story with a conspiratorial laugh and a wrinkle in her eye, as if the answer might still be in doubt. She recalled approaching me on one particular occasion as I rocked away in my own little world.

"June," she called.

No response.

"June," she called again."

Sitting on Harry in the corner of the dining room, I looked out over a ridge at the morning fog. Gradually, shape occurred. It was oval, the color of autumn leaves. I strained to make it out and vaguely heard my name. Then the room came into focus, and I found myself looking into Peggy's lean, caramel-colored face. She wore a concerned expression.

"Come on," Aunt Peggy said. It's time for your bath and to get ready for bed.

Bathing together was a daily ritual for Mommie and me: we luxuriated in a tub of bubbles and giggled over the day's events like two girlfriends having tea.

"We don't have any bubble bath," Aunt Peggy said the first time I asked her for my bottle of bubble bath.

"Are you going to get in the tub with me?" I asked.

"No, this is your bath."

"But if it's my bath, why can't I have bubbles? I persisted.

"I told you, we don't have any. Besides, you'll spill them all over the floor and make a mess."

"I don't make a mess in New York," I whined.

"Child, get in that water and stop making such a fuss," Peggy responded, exasperated.

The water barely reached my waist. Exposed, my chest and shoulders felt cold. Mommie and I filled the tub chest high in New York, but the water pressure in Atlantic City was so low that filling the giant claw-foot tub would have taken forever. Besides, Aunt Peggy worried about the water bill. I submerged a washcloth in the water the way Mommie did to cover herself and leaved back, but the ceramic surface of the tub felt cold against my skin, and I jumped back, splashing water onto Peggy-thus making the mess she had predicted.

I tried to create bubbles using a bar of Ivory soap. But instead, of bubbles, a scummy film appeared in the water.

"Ush! Dirt! I want to get out!"

"That's dirt from you," Peggy said, handing me a worn washcloth. "Here, take some soap and scrub that dirty neck."

"If there were bubbles, there wouldn't be any dirt," I muttered.

Peggy sighed and got down on her knees. She took the washcloth, put some soap on it, and started scrubbing my arms and face and the back of my neck. Her hands were larger than Mommie's, her fingers more slender, her nails longer, filed into ovals, ridged and unpolished. Occasionally, a nail poked through the threadbare washcloth and caught my skin, each pinch a reminder that this was not New York, that Mommie wasn't here, and that there were no bubbles.

"Ow!" I said, as Peggy's finger dug inside my ears.

"Did I hurt you? I'll be softer," Peggy said.

Mommie wore no rings, but Peggy wore three on her left hand: a diamond wedding band and engagement ring on the third finger and a jade oval on her pinkie. Now she removed the rings and placed them in the metal soap dish that hooked over the side of the tub. I watched them floating in the soapy water as Peggy attacked the dirt on the back of my neck. The shadow there never disappeared. Mommie told Peggy it was a birthmark, but to Peggy, it looked more like caked dirt.

By the time she gave up, that washcloth was worn through. Mommie came to visit often during those first months I lived in Atlantic City. But she had as much trouble as I did accepting some of the customs in Peggy and Paul's house.

One time we gathered at the gray linoleum dinner table to say grace. Mommie sat across from me, Paul and Peggy across from each other. I sat, head bowed, eyes closed, the way they had taught me.

Paul started grace. Maybe because Mommie was there, he did a longer version, the one that called on the Virgin Mary to bless the food we were about to eat by the grace of Our Lord.

I cocked my head and opened my right eye to peek up at Mommie.

Her head was cocked too, left eye open, peeking down at me. Her expression said, You and I both know this is a bunch of poppycock.

In spite of ourselves, we started to giggle. Paul droned on, barely pausing. When he finished, he stared down into his plate and remained silent.

Struck by how Mommie's presence had altered the dinner-table dynamics, and still snickering, I glanced at him, then Peggy, who seemed flustered.

"Er, I don't like that," Peggy said, after a pause, refereeing to our disrespect of the grace ritual.

Mommie and I just giggled some more.

I liked to compare my life in New York with my life in Atlantic City. Sometimes I kept lists.

Peggy was fifty years old. Mommie was 36. I was four and a half.

New York had big skyscrapers made out of cement. Atlantic City had little houses made out of wood. In New York it took two and a half strides to get from one crack to the next sidewalk. In Atlantic City I could do it in one stride.

New York had playgrounds with swings and monkey bars where children could go and play. In Atlantic City, you played in the dirt.

There were two kinds of dirt in Atlantic City: the dark earth that Peggy's flowers grew in, and the beige sand at the beach. If I dug deep into Peggy's flower bed, which I wasn't supposed to do, dark dirt yielded to the beige sand, as if the earth had tanned.

The sand at the beach was fine, like sugar. In New York the sand in the playground sandbox was course, like the batter of Peggy's fried chicken before she dipped it.

In New York you lived in an apartment high above the streets, where you could look out and see over the world.

In Atlantic City you lived in a house and could only see down the block, but everyone at the store knew your name.

I had a hard time figuring out all the different Gods. Peggy's was called Episcopalian. She shared him with her best friend, Aunt Hugh. Paul's was Catholic. He shared his with Italians.

Paul's God had a Mommie called Virgin Mary. If you wanted something, you prayed to Virgin Mary, he said, ands he talked to God.

Paul's priest talked to god, too, but he did it in a language only he, the Italians, and God could understand-or so Aunt Peggy said.

Mommie didn't trust organized religion. He friend and my godmother, Mikki in New York, had a God who was Christian Scientist. She was trying to make him be Mommie's God. Mikki told me that her God lived all around me, and on the nights I wanted my dreams to take me back home, I prayed to him. I figured that Paul's God's mommie would be too busy listening to everyone else's prayers, While Peggy's God seemed to live far, far away; too far, it seemed to even hear the prayers of a child.

St bedtime in Atlantic City, I would put on my pajamas and kneel on the oval green shag rug next to the twin bed against the wall. Aunt Peggy would kneel beside me.

First we did the prayer that my Godmother Mikki had taught me:

Father-Mother God, Loving me- Guard me when I sleep Guide my little feet Up to Thee

Then we worked on a longer Prayer Peggy was teaching me. She called it the Lord's Prayer. Peggy had shown me a picture of her Lord God in the Bible. He had white hair and a long white beard, this God, who had his name hallowed out in a log somewhere, and you had to beg his forgiveness for stepping on it.

Peggy said all these Gods were the same, and I shouldn't try so hard to distinguish them from one another. Sometimes, when I recited my lists of comparisons to her, she would pucker her brows and lips simultaneously, and tell me that I should accept things as they were and stop making differences.

So after a while, I just kept lists in my head.

# # #

I search for my mother's face in the mirror and see a stranger. Her face is toffee-colored and round; her eyes, the eyes of a foreigner, slanted and brown. They are not my mother's eyes: irises of brilliant green, set obliquely in almond-shaped sockets above high cheekbones.

They said I looked exotic, she classic. Together-a bamboo-colored redhead carrying her olive-sinned, curly-haired toddler-together, we seemed alien. Skin fractured our kinship.

When I was young, riding in the supermarket cart's basket, strangers looked from me to her and back again.

"She's so cute! Is she yours?" they'd ask.

"Yes, she's mine," Mommie would answer before turning the basket in another direction. Looking behind her, sometimes I saw their faces turn sour. I learned to recognize the expression well before I knew what it meant.

At night, before she put me to bed, Mommie and I would find our likenesses. She would ask, 'Who's got a perfect little forehead?"

I'd point above my brows.

"You do!" She'd say with a nod. 'Who's got a perfect little nose?"

"I do!" I'd say, and she would agree again.

"Who's got perfect little hands?"

"We do!"

We laughed over this, our shared proportions: our hands shaped alike-the pinkie exactly half the length of the ring finger, the index and ring fingers each a half inch shorter than the second digit, our nails shaped the same. Even the arches of our feet arced in the same curve, and our toes, too, had a similar square outline.

My mother was an aspiring actress. We lived in the orbit of show business and its backstage shenanigans, where races mixed out of sight of the public. She had separated from my father, a well-known song-and-dance man, shortly after I was born, in January 1954, six months before the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision desegregated the country's schools.

By the time I was three, Negroes in Montgomery, Alabama, had forced the city to integrate its city buses. In Manhattan the buses were already integrated, but an immutable social line nevertheless divided the races, even in the Upper West Side building where Mommie and I lived. African Americans worked there as elevator men but could not rent apartments. The civil-rights movement had not made a dent in our social sphere.

"She looks Chinese," acquaintances guessed, considering the fold of my eyes, the pale olive cast of my skin, my full lips. Oriental-looking, said the middle-aged woman who took care of me much of the time, whom I would come to call "Aunt Peggy."

Aunt Peggy was trying to soothe my feelings-"Oriental-looking Negro women were considered pretty back then-but I knew I wasn't Oriental. Wrapped in a bright yellow towel after my bath, I contemplated the women in the framed Gauguin prints on our walls: their seal-slick black manes, their knowing smiles. Even as a toddler, I somehow grasped that these women would not have considered me Oriental. My mother liked to call me "Tahitian June," but if I were really Tahitian, why wasn't my hair waist long like theirs?

My skin had not yet fully darkened, and my mother lived in fear that we would be found out.

'She'd pass if it weren't for her hair," I overheard Mommie say one day, and my heart collapsed. I didn't know what she meant by that word 'pass" but the tone in her voice sounded the way the faces of the people in the supermarket looked.

I went to the bathroom, climbed atop the toilet seat, and leaned over the sink to explore my short, soft, frizzy curls in the mirror.

My mother's hair fell over her eyes in a bouncy auburn flip that flirted with the world. My hair didn't flip. My curls, soft when they were less than an inch long, frizzed straight out if they grew longer. Mommie made sure they didn't get that long. Cute, Aunt Peggy called my boyish cut. Unusual for a girl, she'd say as she smoothed her own wavy black hair into a French twist. She looked at me in a half-cocked way that meant she didn't really think it was cute, but odd.

In front of the mirror, I tried to pull my hair back with my mother's tortoiseshell comb. The fragile teeth snapped, tangling like splintered tears in my curls.

As far back as I could remember, Mommie traveled. When I was a baby, she took me with her on the plane: by the age of two, I had traveled to Detroit, Las Vegas, and Chicago-I had baby-sized spoons and forks and souvenirs. Once I was able to walk, she would announce she had an audition for an acting job or modeling assignment and, before going, take me to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where she left me with Aunt Peggy and her husband, Uncle Paul.

"I'm visiting Atlantic City, but I really live in New York," I would tell everyone, with my native New Yorker's air of superiority. Moving back and forth between the small seaside town and the big concrete city, I would compare everything, and everything seemed to lead me back to the contours of my face. My mother's lips were primly thin-she wore the stoic expression of a pilgrim. My mouth was broad; my full lips framed a toothy smile. 'You have your father's mouth," Aunt Peggy said when I asked her why I didn't look like Mommie. She told me not to smile so broadly-it showed my gums to my disadvantage.

Then I would kneel on a chair in the dining room, balancing my left arm on the credenza against the wall, and look in the large wall mirror. I practiced curbing my smile. Sometimes I made faces at myself and laughed.

"If Norma doesn't want anybody to know who she is, she better not laugh," Paul commented to Peggy one day in his gravelly voice.

"That laugh belongs to nobody but Norma."

Norma was my mother's first name. I wondered how my mother's laugh could come from my mouth, which was more like my father's. It had been so long since I'd seen my father that I no longer remembered him. I wondered why my mother didn't want anyone to know who I was. Peggy and Paul seemed to understand the answers to these questions, but when I asked, they would look aside and say offhandedly, 'Oh, you'll learn when you're older."

Back in New York, Mommie didn't treat me like a child. When I asked her why my mouth wasn't shaped like her, she paused barely a second before answering, "Well, that's because you're around me all the time, and we spend so much time together." Her explanation made it seem as natural as the fact that we shared square toes.

She began teaching me how to read tones of voice and hear intent, even when it seemed at odds with what she said. We would often spend the afternoon at the movies, sometimes catching the same movie several days' running, and afterward she explained how actors used their bodies to convey character: the way Loretta Young swept down a flight of stairs like an aristocrat, how Gloria Swanson's Staircase descent at the end of Sunset Boulevard made her seem crazy or Katharine Hepburn's in The Philadelphia Story made her seem like she didn't care about losing her boyfriend, when she really cared a lot. Sunset Boulevard was Mommie's favorite movie; Gigi, with Leslie Caron and Maurice Chevalier, became mine. Although I didn't understand the plots of these movies, Mommie had a talent for choosing the one scene that even a four-year-old could grasp, and at home I played my mother's co-star as we reenacted them.

My mother told me stories about her life that seemed as fantastic as any movie star's. She told me she was part Indian, the granddaughter of an outlaw who had ridden with Jesse James's gang. She said she had studied acting with Marlon Brando. She said she has been an Olympic swimmer.

When she told me that her grandpa had performed tricks on horses for Ringling brothers' circus, I thought she was inventing tales; but that one would turn out, like all her stories, to have a strand of truth.

As a young woman, when telling people the story of my life, I chose my words carefully: "My mother didn't raise me. I was raised in Atlantic City, new jersey."

Sometimes I'd add, 'I was raised by my father's people"-"father's people" being a deliberately vague description that could mean my father's brother and sister, some cousins, or, more generally, the entire dark-hued nation. Depending on the race of the listener and how complicated I wished to make the tale, I described those who raised me as my father's sister, my godmother, or my guardians. Aunt Peggy, who after all was not really my aunt but the guardian in question, preferred the last, but my tongue always stuck on that word-"guardian"-it made me feel like a character in a Dickens novel.

In the vernacular of black America, I was 'taken in," or informally adopted.

My mother and I never talked about her decision, how it affected her, the way she saw me and those who looked like me, or how it affected the way I viewed her and those who looked like her. We tried, several times, but it was too painful. She could not look at me-with my wild Afro, wide hips, and Harlem address-and ignore her Upper West Side apartment with the wraparound balcony, her closets full of designer clothes, or her support for Ronald Reagan.

Still, we tried.

"I don't see you as a black woman when I look at you," she protested, almost making me believe her. 'I see you as mine, all mine. I don't see Jimmy in you at all."

Jimmy. That was my father, James Cross.

During the thirties and forties, he had made his fame as a comic who danced in a duo called Stump and Stumpy (Jimmy was known as 'Big Stump," although he was barely five-eight). Stump and Stumpy were headlines then, during the height of the Jazz Age, playing houses like the Cotton Cub and the Paramount Theater, places where blacks could dance onstage but couldn't sit in the audience. When television replaced variety shows in the early fifties, my father's career began a slow nosedive.

My mother had met him backstage at the Paramount in 1949, before television changed the show business forever. She saw a talented comic at the height of his powers, and he saw what he later remembered as the most beautiful woman he had ever laid eyes on. They began a relationship that lasted for five years.

Aunt Peggy liked to say that she had been the landlord of the apartment where I was conceived, as though she were the biblical Sarah and my mother were some kind of Hagar, but as I figure the dates, my mother was already three months pregnant when she and Jimmy moved into a one-bedroom apartment at 407 North Indiana Avenue, where Peggy, an elementary-school teacher, and Paul, a county clerk, owned a house.

Jimmy had been appearing at Club Harlem, the premier black nightclub in Atlantic City, for the summer season, and Mommie and Peggy became friendly. After my parents moved out, and as their relationship went downhill, Mommie began leaving me with Peggy and Paul. These visits got longer and longer, the tell me, until the summer before I started school, she left me there for good.

That year and the four or five that followed were erased from my memory for a long time. When I asked how I came to live in Atlantic City, Aunt Peggy and Mommie stuck to the same story-they said it had been done gradually, so that I would never know what was going on.

But even at four, I knew that something was amiss. I remember the subtle shift of moving from Mommie's world to Aunt Peggy and Uncle Paul's-from what seemed like an unfettered childhood, where I felt treated as an adult and was at the center of attention to a house where children obeyed rules and learned responsibilities. In Atlantic City adults no longer included me in their conversation. If they asked what I thought, it was in a tone reserved for babies. Aunt Peggy and Uncle Paul would sometimes drop their voices low and when I entered the room, looking at me with studied nonchalance and frozen smiles when I asked what they were talking about.

The hardest thing was adjusting to the food.

Mommie cooked simply-grilled meat and a steamed vegetable was our usual fare, while Aunt Peggy's food was heavier and spicy. One night she fixed pork chops with string beans for dinner. The meat was overcooked, the flavoring strange, the string beans a pile of mush accompanying a quarter of the plate. Mommie has always said I had to taste everything and show manners when I was a guest. I managed to swallow the meat, but refused the string beans.

Uncle Paul, his voice cracked by emphysema, ordered me to eat my string beans in his Billy Goat Gruff tone.

I refused.

He insisted, and I refused instantly. Aunt Peggy tries to intervene, joking that Uncle Paul has been a corporal in the army and sometimes it seemed he had never left. He cut his hazel eyes at her, warning her to stay out of this. Then he looked at me.

"You're not leaving this table until you eat your vegetables," he declared.

"I won't and you can't make me!" I shot back.

The battles lines had been drawn. They wouldn't let me leave, but I could make dinner unpleasant for them. I scraped the string beans from one side of the plate to the other with my fork while kicking the table underneath with my heavy oxford shoes.

Finally I was sent upstairs, to my room above the kitchen. Mommie had never made me eat food I didn't want. She would never have banished me from the dinner table. I stomped on the gray linoleum floor, knowing the noise would interrupt Peggy and Paul's dinner.

I heard murmuring below-Paul wanted to come upstairs, but Peggy was telling him firmly to let me get it out of my system. I would show them. I dragged my desk chair to the top of the stairs and pushed it down. It rattled down the steps with such a ruckus that it startled even me, but when no one came, I picked up the little pink stool from the night table and sent it down to. Then all my dolls. And then my books.

A nice-nice heap was growing at the front door of the stairs when the phone rang. I could tell from Aunt Peggy's voice after she answered that it was my mother. I redoubled my efforts then, screaming and crying as loud as I could.

After a while, Aunt Peggy called me to the phone. I pounded down the stairs, grunting and sobbing as I stepped over the pile of furniture on the landing, drooling, my eyes nearly swollen shut from my crying. Taking the phone from Peggy, I poured out the whole story to Mommie. I thought surely she would come on the next bus and save me from these mean people and their nasty food.

Instead she just listened and then quietly said, "You must do as Peggy tells you."

I protested, but she repeated herself and she told me to go, immediately, and apologize to Paul. Her quiet voice carried more authority than all of his haranguing. I hung up the phone and did as she said.

Then Aunt Peggy made me carry everything up the stairs.

In Aunt Peggy's house, I spent hours on my rocking horse, Harry.

Harry had been a present to me from my mother's then boyfriend, an Italian janitor from the Bronx. I had named him after the singer Harry Belafonte, whose 1956 Calypso album had just become the first album to sell over a million copies. "Day-O" was one of my favorite songs, not least for its refrain, "Daylight comes and me wan' go home."

Peggy and Paul had placed Harry opposite the big upholstered chair where Peggy liked to sit while chatting on the phone. I would Pat Harry's neck the way I'd seen the Lone Ranger pat his horse, Silver, on TV, and Harry would come alive. When I spurred his hide, his hollow body answered with a sound as big as the echo across a valley. Away we'd ride, Susannah of the Mounties and Harry, traveling through the Western Territories.

I imagine that I was a girlish Barbara Stanwyck, chasing the bad guys through the crags and gullies in the northern Rocky Mountains. Mother had left me to tend the ranch by myself for a couple of days while she helped the army scout Indians down In Georgia.

Peggy and Paul would watch as I rocked back and forth, oblivious to my surroundings. Once Paul looked at Peggy nervously. "Hey you think she's all right?" he asked. He said "all right" in the tone you use when you are wondering if someone's cuckoo.

When I was a teenager, Peggy told me this story with a conspiratorial laugh and a wrinkle in her eye, as if the answer might still be in doubt. She recalled approaching me on one particular occasion as I rocked away in my own little world.

"June," she called.

No response.

"June," she called again."

Sitting on Harry in the corner of the dining room, I looked out over a ridge at the morning fog. Gradually, shape occurred. It was oval, the color of autumn leaves. I strained to make it out and vaguely heard my name. Then the room came into focus, and I found myself looking into Peggy's lean, caramel-colored face. She wore a concerned expression.

"Come on," Aunt Peggy said. It's time for your bath and to get ready for bed.

Bathing together was a daily ritual for Mommie and me: we luxuriated in a tub of bubbles and giggled over the day's events like two girlfriends having tea.

"We don't have any bubble bath," Aunt Peggy said the first time I asked her for my bottle of bubble bath.

"Are you going to get in the tub with me?" I asked.

"No, this is your bath."

"But if it's my bath, why can't I have bubbles? I persisted.

"I told you, we don't have any. Besides, you'll spill them all over the floor and make a mess."

"I don't make a mess in New York," I whined.

"Child, get in that water and stop making such a fuss," Peggy responded, exasperated.

The water barely reached my waist. Exposed, my chest and shoulders felt cold. Mommie and I filled the tub chest high in New York, but the water pressure in Atlantic City was so low that filling the giant claw-foot tub would have taken forever. Besides, Aunt Peggy worried about the water bill. I submerged a washcloth in the water the way Mommie did to cover herself and leaved back, but the ceramic surface of the tub felt cold against my skin, and I jumped back, splashing water onto Peggy-thus making the mess she had predicted.

I tried to create bubbles using a bar of Ivory soap. But instead, of bubbles, a scummy film appeared in the water.

"Ush! Dirt! I want to get out!"

"That's dirt from you," Peggy said, handing me a worn washcloth. "Here, take some soap and scrub that dirty neck."

"If there were bubbles, there wouldn't be any dirt," I muttered.

Peggy sighed and got down on her knees. She took the washcloth, put some soap on it, and started scrubbing my arms and face and the back of my neck. Her hands were larger than Mommie's, her fingers more slender, her nails longer, filed into ovals, ridged and unpolished. Occasionally, a nail poked through the threadbare washcloth and caught my skin, each pinch a reminder that this was not New York, that Mommie wasn't here, and that there were no bubbles.

"Ow!" I said, as Peggy's finger dug inside my ears.

"Did I hurt you? I'll be softer," Peggy said.

Mommie wore no rings, but Peggy wore three on her left hand: a diamond wedding band and engagement ring on the third finger and a jade oval on her pinkie. Now she removed the rings and placed them in the metal soap dish that hooked over the side of the tub. I watched them floating in the soapy water as Peggy attacked the dirt on the back of my neck. The shadow there never disappeared. Mommie told Peggy it was a birthmark, but to Peggy, it looked more like caked dirt.

By the time she gave up, that washcloth was worn through. Mommie came to visit often during those first months I lived in Atlantic City. But she had as much trouble as I did accepting some of the customs in Peggy and Paul's house.

One time we gathered at the gray linoleum dinner table to say grace. Mommie sat across from me, Paul and Peggy across from each other. I sat, head bowed, eyes closed, the way they had taught me.

Paul started grace. Maybe because Mommie was there, he did a longer version, the one that called on the Virgin Mary to bless the food we were about to eat by the grace of Our Lord.

I cocked my head and opened my right eye to peek up at Mommie.

Her head was cocked too, left eye open, peeking down at me. Her expression said, You and I both know this is a bunch of poppycock.

In spite of ourselves, we started to giggle. Paul droned on, barely pausing. When he finished, he stared down into his plate and remained silent.

Struck by how Mommie's presence had altered the dinner-table dynamics, and still snickering, I glanced at him, then Peggy, who seemed flustered.

"Er, I don't like that," Peggy said, after a pause, refereeing to our disrespect of the grace ritual.

Mommie and I just giggled some more.

I liked to compare my life in New York with my life in Atlantic City. Sometimes I kept lists.

Peggy was fifty years old. Mommie was 36. I was four and a half.

New York had big skyscrapers made out of cement. Atlantic City had little houses made out of wood. In New York it took two and a half strides to get from one crack to the next sidewalk. In Atlantic City I could do it in one stride.

New York had playgrounds with swings and monkey bars where children could go and play. In Atlantic City, you played in the dirt.

There were two kinds of dirt in Atlantic City: the dark earth that Peggy's flowers grew in, and the beige sand at the beach. If I dug deep into Peggy's flower bed, which I wasn't supposed to do, dark dirt yielded to the beige sand, as if the earth had tanned.

The sand at the beach was fine, like sugar. In New York the sand in the playground sandbox was course, like the batter of Peggy's fried chicken before she dipped it.

In New York you lived in an apartment high above the streets, where you could look out and see over the world.

In Atlantic City you lived in a house and could only see down the block, but everyone at the store knew your name.

I had a hard time figuring out all the different Gods. Peggy's was called Episcopalian. She shared him with her best friend, Aunt Hugh. Paul's was Catholic. He shared his with Italians.

Paul's God had a Mommie called Virgin Mary. If you wanted something, you prayed to Virgin Mary, he said, ands he talked to God.

Paul's priest talked to god, too, but he did it in a language only he, the Italians, and God could understand-or so Aunt Peggy said.

Mommie didn't trust organized religion. He friend and my godmother, Mikki in New York, had a God who was Christian Scientist. She was trying to make him be Mommie's God. Mikki told me that her God lived all around me, and on the nights I wanted my dreams to take me back home, I prayed to him. I figured that Paul's God's mommie would be too busy listening to everyone else's prayers, While Peggy's God seemed to live far, far away; too far, it seemed to even hear the prayers of a child.

St bedtime in Atlantic City, I would put on my pajamas and kneel on the oval green shag rug next to the twin bed against the wall. Aunt Peggy would kneel beside me.

First we did the prayer that my Godmother Mikki had taught me:

Father-Mother God, Loving me- Guard me when I sleep Guide my little feet Up to Thee

Then we worked on a longer Prayer Peggy was teaching me. She called it the Lord's Prayer. Peggy had shown me a picture of her Lord God in the Bible. He had white hair and a long white beard, this God, who had his name hallowed out in a log somewhere, and you had to beg his forgiveness for stepping on it.

Peggy said all these Gods were the same, and I shouldn't try so hard to distinguish them from one another. Sometimes, when I recited my lists of comparisons to her, she would pucker her brows and lips simultaneously, and tell me that I should accept things as they were and stop making differences.

So after a while, I just kept lists in my head.

# # #

Descriere

In this poignant memoir and follow-up to Cross' Emmy Award-winning documentary, she deftly portrays the strains of a complicated family structure, ruptured by race, secrecy, and human fallibility.