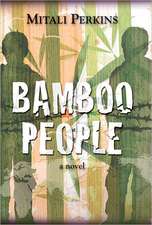

Secret Keeper

Autor Mitali Perkinsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2010 – vârsta de la 12 ani

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 84.12 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 126

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.10€ • 16.93$ • 13.30£

16.10€ • 16.93$ • 13.30£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 16-30 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440239550

ISBN-10: 0440239559

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 161 x 204 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Delacorte Press Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 0440239559

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 161 x 204 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Delacorte Press Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Mitali Perkins was born in Kolkata, India. Her previous novel with Delacorte Press is Monsoon Summer, a Book Sense 76 Pick, a New York Public Library Book for the Teenage, and a Bank Street College Best Book. She lives in Newton, Massachusetts.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

ONE

Asha and Reet held their father's hands through the open window. The train picked up speed slowly, and Baba jogged, then ran alongside it. As his fingers slipped from their grasp, the girls turned and watched him dwindle and disappear into the Delhi haze.

"Watch your head, Osh!" Reet cried suddenly, pulling her sister inside before the train sliced into a tunnel.

The train swerved in the darkness, and Asha grabbed her sister's arm. Usually their mother would have issued the warning long before Reet had. But sometimes Ma was in the clutches of the Jailor, the girls' label for the heavy gloom that often fell over her like a shroud. Was she already so remote that the possibility of her daughter's decapitation couldn't rouse her?

When the train chugged out of the tunnel, Asha could hardly believe what she saw. Their mother's face was buried in her hands, and tears--wet, salty tears--were staining her powdery cheeks in widening brown stripes.

What was happening? This had to be a mistake--there was no way Sumitra Gupta could be crying. The girls had seen their father get choked up many times, even while Ma or Reet sang about rain, grief, or heartache. But their mother never cried, retreating instead into stony silence that could last for hours, days, weeks. Even months, as it had after she'd read the telegram telling of her own mother's death.

But now Ma was crying. She was actually crying. The girls exchanged shocked looks. Then Reet sat down and gathered their mother in her arms.

Asha watched in amazement. This was Ma, who had ruled their household--and the entire social circle of Bengali families in Delhi--for years. To see her weeping on Reet's shoulder felt like watching a fortress crumble into a million pieces. And yet there was Reet--holding and comforting Ma as though their mother had become someone else altogether.

Asha sat down on the other side of her sister, an unusual sensation of pity softening her heart. Although she didn't touch Ma or say anything, she could feel the ache of missing Baba drawing them together.

She remembered Baba's last-minute request the night before: "If your ma gets like, well, like she does sometimes, I'm counting on you girls to lift her spirits. Promise me you'll take care of your mother and each other until you join me."

"We will, Baba," Reet had said, but her voice had sounded as doubtful as Asha felt.

"Keep this money and use it to buy her favorite sweets, Tuni," Baba had added, handing a small purse to Asha, who tucked it into her bag. Tuni was her childhood nickname, short for Tuntuni bird, the hero of a host of Bengali folktales.

Once the train was far out into the countryside, Ma pulled away from Reet's arms and sat up. She wiped the last trace of powder from her cheeks with one end of her saree and tucked loose wisps of hair back into her bun. "Forgive my sorrow, girls," she said in a low voice, still not looking at them. "I've only been away from your baba twice since our marriage day."

"We understand," Asha said.

Reet nodded. "This is the worst thing that's happened yet," she said, shifting the conversation from Bangla into English. The girls had fallen into the habit of speaking English to each other, like most Bishop Academy students. "Why couldn't we have all left for America together?"

"That would have been wonderful," Asha said wistfully. "I wouldn't have minded losing the flat, or selling the furniture, or even saying goodbye to the school if we could have gone to New York straightaway with Baba."

"Leaving school was hard, though, Osh," Reet said. "You looked heartbroken when Baba told us we couldn't afford the tuition anymore." Osh was Asha's nickname at school, and Reet had fallen into the habit of using it. Asha, too, called her sister Reet, which was their schoolmates' way of shortening the more formal Amrita.

"Don't say anything about money in front of the relatives," Ma said sharply, sounding like herself again and yanking the conversation back into Bangla. "Your father will find a job soon; there's no use worrying your grandmother."

The word was that while England was flooded with Indian job candidates, American companies were just starting to hire foreign engineers. Asha only hoped that people all the way on the other side of the world realized that the Indian economy was in shutdown after months of strikes and protests, and that being jobless for four months wasn't Baba's fault. She wasn't sure she could survive a long stay in Calcutta with her father's side of the family. This would be their third visit from Delhi, the first without a scheduled departure date--and none of Baba's jokes to smooth over the tension.

Judging by the heavy silence, Reet and Ma were also imagining the bleakness of a Baba-less visit to Calcutta. One glance at Ma's face told Asha that the Jailor was threatening to close in again. Quickly she leaned forward, using Bangla so she could give her mother an honorific "you" to convey an extra measure of respect. "Why don't you tell us how you and Baba met, Ma? He tells his side, but we've never heard yours."

To Asha's relief, Ma nodded, slipped off her sandals, and settled herself into a cross-legged position. Their mother's toenails were painted pale pink, matching the tiny flowers embroidered on the border of her saree. Her sandals were gold, echoing the thread that made the silk shimmer with her graceful moves. She certainly looked the part of a refined, prosperous, urban housewife; any traces of a village girl had disappeared long ago.

From the Hardcover edition.

Asha and Reet held their father's hands through the open window. The train picked up speed slowly, and Baba jogged, then ran alongside it. As his fingers slipped from their grasp, the girls turned and watched him dwindle and disappear into the Delhi haze.

"Watch your head, Osh!" Reet cried suddenly, pulling her sister inside before the train sliced into a tunnel.

The train swerved in the darkness, and Asha grabbed her sister's arm. Usually their mother would have issued the warning long before Reet had. But sometimes Ma was in the clutches of the Jailor, the girls' label for the heavy gloom that often fell over her like a shroud. Was she already so remote that the possibility of her daughter's decapitation couldn't rouse her?

When the train chugged out of the tunnel, Asha could hardly believe what she saw. Their mother's face was buried in her hands, and tears--wet, salty tears--were staining her powdery cheeks in widening brown stripes.

What was happening? This had to be a mistake--there was no way Sumitra Gupta could be crying. The girls had seen their father get choked up many times, even while Ma or Reet sang about rain, grief, or heartache. But their mother never cried, retreating instead into stony silence that could last for hours, days, weeks. Even months, as it had after she'd read the telegram telling of her own mother's death.

But now Ma was crying. She was actually crying. The girls exchanged shocked looks. Then Reet sat down and gathered their mother in her arms.

Asha watched in amazement. This was Ma, who had ruled their household--and the entire social circle of Bengali families in Delhi--for years. To see her weeping on Reet's shoulder felt like watching a fortress crumble into a million pieces. And yet there was Reet--holding and comforting Ma as though their mother had become someone else altogether.

Asha sat down on the other side of her sister, an unusual sensation of pity softening her heart. Although she didn't touch Ma or say anything, she could feel the ache of missing Baba drawing them together.

She remembered Baba's last-minute request the night before: "If your ma gets like, well, like she does sometimes, I'm counting on you girls to lift her spirits. Promise me you'll take care of your mother and each other until you join me."

"We will, Baba," Reet had said, but her voice had sounded as doubtful as Asha felt.

"Keep this money and use it to buy her favorite sweets, Tuni," Baba had added, handing a small purse to Asha, who tucked it into her bag. Tuni was her childhood nickname, short for Tuntuni bird, the hero of a host of Bengali folktales.

Once the train was far out into the countryside, Ma pulled away from Reet's arms and sat up. She wiped the last trace of powder from her cheeks with one end of her saree and tucked loose wisps of hair back into her bun. "Forgive my sorrow, girls," she said in a low voice, still not looking at them. "I've only been away from your baba twice since our marriage day."

"We understand," Asha said.

Reet nodded. "This is the worst thing that's happened yet," she said, shifting the conversation from Bangla into English. The girls had fallen into the habit of speaking English to each other, like most Bishop Academy students. "Why couldn't we have all left for America together?"

"That would have been wonderful," Asha said wistfully. "I wouldn't have minded losing the flat, or selling the furniture, or even saying goodbye to the school if we could have gone to New York straightaway with Baba."

"Leaving school was hard, though, Osh," Reet said. "You looked heartbroken when Baba told us we couldn't afford the tuition anymore." Osh was Asha's nickname at school, and Reet had fallen into the habit of using it. Asha, too, called her sister Reet, which was their schoolmates' way of shortening the more formal Amrita.

"Don't say anything about money in front of the relatives," Ma said sharply, sounding like herself again and yanking the conversation back into Bangla. "Your father will find a job soon; there's no use worrying your grandmother."

The word was that while England was flooded with Indian job candidates, American companies were just starting to hire foreign engineers. Asha only hoped that people all the way on the other side of the world realized that the Indian economy was in shutdown after months of strikes and protests, and that being jobless for four months wasn't Baba's fault. She wasn't sure she could survive a long stay in Calcutta with her father's side of the family. This would be their third visit from Delhi, the first without a scheduled departure date--and none of Baba's jokes to smooth over the tension.

Judging by the heavy silence, Reet and Ma were also imagining the bleakness of a Baba-less visit to Calcutta. One glance at Ma's face told Asha that the Jailor was threatening to close in again. Quickly she leaned forward, using Bangla so she could give her mother an honorific "you" to convey an extra measure of respect. "Why don't you tell us how you and Baba met, Ma? He tells his side, but we've never heard yours."

To Asha's relief, Ma nodded, slipped off her sandals, and settled herself into a cross-legged position. Their mother's toenails were painted pale pink, matching the tiny flowers embroidered on the border of her saree. Her sandals were gold, echoing the thread that made the silk shimmer with her graceful moves. She certainly looked the part of a refined, prosperous, urban housewife; any traces of a village girl had disappeared long ago.

From the Hardcover edition.