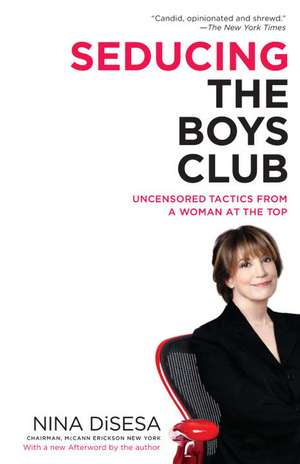

Seducing the Boys Club: Uncensored Tactics from a Woman at the Top

Autor Nina DiSesaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2008

Fact #2: The playing field is not level.

Fact #3: You need to get over this.

Chairman of the flagship office of the largest advertising agency network in the world, Nina DiSesa is a master communicator, a ceiling crasher, and a big-time realist. In Seducing the Boys Club, DiSesa shows you how S&M–seduction and manipulation–is the secret to winning over (and surpassing) the big guys. She asserts that women need to meld their “female” characteristics (nurturing, compassion, intuition) with “male” traits (decisiveness, focus, confidence, humor) to expand their professional horizons. DiSesa also shares her practical, outrageous, and even controversial maxims for making it, including

• Learn to appreciate men. Men like women who like them.

• Remember that women are biologically wired to succeed.

• If you want to make a name for yourself, find a mess and fix it. A secure and comfortable job only holds you back.

• Act brave and you will look brave.

• Screw the rules. Make up your own.

Whether dead-on funny or deadly serious, DiSesa is always on her game, always on message, and absolutely on target as she arms women (men, too!) with the can-do confidence and no-compromises attitude they need to climb as high as their ambition can carry them–while keeping their standards impeccable and their integrity intact.

Preț: 117.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 176

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.50€ • 23.21$ • 18.78£

22.50€ • 23.21$ • 18.78£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345496997

ISBN-10: 034549699X

Pagini: 227

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 034549699X

Pagini: 227

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Nina DiSesa has worked in the quintessential boys clubs of advertising for almost thirty years. In 1994, she became the first woman EVP, Executive Creative Director for McCann Erickson New York, the flagship office of the largest advertising agency in the world. Under her creative leadership, the New York office enjoyed an unprecedented 5-year growth period adding almost $2.5 billion in billings. In 1998, she was made Chairman as well as Chief Creative Officer of McCann New York. She was the first woman and first creative director to be named chairman in the McCann global network.

In 1999, Nina was chosen by Fortune magazine as one of the “50 Most Powerful Women in American Business.” In 2005, she received the Matrix Award, given each year to a select group of women in communication. In 2007, she was inducted into the Hall of Fame for CEBA (Creative Excellence in Business Advertising).

Nina and her husband live in an apartment in NYC and escape to their 45-acre horse farm in Dutchess County, New York.

From the Hardcover edition.

In 1999, Nina was chosen by Fortune magazine as one of the “50 Most Powerful Women in American Business.” In 2005, she received the Matrix Award, given each year to a select group of women in communication. In 2007, she was inducted into the Hall of Fame for CEBA (Creative Excellence in Business Advertising).

Nina and her husband live in an apartment in NYC and escape to their 45-acre horse farm in Dutchess County, New York.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

My Life Started in an Elevator

I wasn’t actually born in an elevator. Or conceived in one. (How freaky would that be? Can you imagine your parents doing it in an elevator?) My career started in an elevator, and that was the beginning of my real life, the one I don’t look back on and shudder at. It happened one Saturday morning in May. I was with my first husband, a crabby actor I had married four years earlier because I thought I could cheer him up. We had just left our sixth-floor Manhattan apartment to go grocery shopping and, when the elevator doors closed, my husband announced that he had made a decision. I thought he’d decided what he wanted for dinner.

No. He had come to the conclusion that he didn’t love me anymore.

When we reached the fourth floor he said that, upon reflection, he probably never had.

By the time we got to the lobby, he confessed that he was in love with another woman.

His entire revelation took less than sixty seconds. Then we went shopping for food. I bought a nice eye-of-round roast. It was on sale. I even cooked it for the little shit.

A week later he packed up and left, and I sprang into action. I painted the bedroom an insomnia-inducing shade of bubble gum pink because he’d never let me decorate our apartment the way I wanted and I needed to assure myself that I was in control of my life. It made me feel like I was sleeping in a giant lung, but I didn’t care. It was my lung now and I could do with it what I wanted. Then I stopped eating the junk food that was a substitute for you-know-what and lost thirty-five pounds in six months. (Isn’t that great?) And I quit my job writing resort ads for the Catskills (“Shecky Greene! Here thru Labor Day!”), because I realized I was not going to have a family anytime soon and I needed to think seriously about a career.

Oh, and during those first six months, when I was losing all that weight, I also wept. (I wonder how much of the thirty-five pounds had been water retention.) I cried all the time. Not because I missed my unfaithful husband, but because I felt abandoned, defeated, and convinced that no one would ever love me or even like me. I had no career, no future, and no one to blame.

I was twenty-eight.

Not a very promising beginning on the road to chairman.

I had two big “aha”s after being dumped on that elevator: First, being with the wrong man is worse than having no man at all, and second, I was totally unprepared for a career because I wasn’t good at anything. I had to change that quickly and become skilled at something of value. Luckily, I thought I could write. But I had a long road ahead of me, and I had wasted six precious years on a dead-end relationship. (We dated two years before the wedding. You’d think I would have caught on sooner.)

After I got tired of feeling sorry for myself (right around the time my body went from a size 14 to an 8), I found a job as a copywriter at Howard Marks Advertising in New York. Unlike the job writing resort ads for the Catskills, this one required talent. I had to find some of that and fast.

I was hired as a temporary employee after a thirty-minute interview with Howard Marks himself. He didn’t need much more time than that to see that I was wounded, insecure, and needy—the three traits he loved the most in another person. It turned out that Howard collected damaged souls. It provided him with built-in dedication from his employees and, to be fair, he also liked to save lives. He certainly didn’t hire me for the brilliance of my Catskills resort ads.

All Howard wanted from me was unconditional loyalty and funny radio commercials for the retail clients he served in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. Places like the local Arby’s franchise and Cleveland Tux Rentals. I was positive that I could be funny—if I could just stop crying.

Working for Howard was my first experience being in the power of a controlling person. He combined skillful manipulation with a sprinkling of child psychology and a pinch of positive reinforcement. I watched a master control me in the same way he controlled all the people who worked for him. I saw him get better work from us all without really asking for it. He did it by making us desperate for his approval and by keeping us off balance. We never knew when the happy, charming Howard would show up for work or when the mean, irritable Mr. Marks would be joining us for a verbal whipping. I think this was more a result of his blood-sugar levels than any psychological issue. He was always on a diet and believed he could eat as much as he wanted if the foods were low in fat. He would eat mounds of steamed shrimp for lunch and point to his overflowing plate and say gleefully, “No calories!” Looking back, I’m sure he had high cholesterol as well as diabetes.

In his more lucid moments, Howard wished for creative nirvana.

“If I could only convince people to be more creative,” he told me once, “I would be rich.”

Howard couldn’t enforce creativity, but he could give us enough confidence to open up our minds and release any dormant brilliance lurking inside.

He also taught me that you couldn’t legislate loyalty. Howard knew how to make us want to please him, especially on the days we were confident he wouldn’t fire us all in a fit of fury. Here’s how he seduced and manipulated me: Howard would give me an assignment to write a radio script. I’d write something and drop it in his in-box for approval. Then he would return it with his comments and the reason he rejected it. (There was only one reason: “Not funny!”) After a few misses, I finally got a script with “Good.” written in the upper-right-hand corner. I was really pleased. When I showed the script to the people on his staff, they kindly explained his code to me. “Good.” with a period meant it was just okay and he could live with it. It was up to me to decide whether I could live with it. “Good!” with an exclamation point meant he liked it. After that, they said, his comments were self-explanatory.

The first time I got a “Good!” from Howard I felt great! But I wanted his approval so much that I would try to do even better. When a script finally came back with “GREAT!” written in the upper corner, I was elated. That spurred me on to take bigger chances, and with my confidence growing, I would dash out scripts that actually brought a smile to my own miserable face. After a while, I got the greatest compliment Howard could give: A script came back to me with “BRILLIANT!!!” scribbled at the top.

Yes, I thought, I was brilliant. It was a radio spot for Cleveland Tux about a hapless groom who forgot he was getting married until the day before the wedding. His friends urged him to go to Cleveland Tux because he could get fitted quickly, and if his fiancée killed him, he could always use the tux for his funeral. “It’s a win-win situation,” his best man assured him.

At the end of my thirty-day trial period, Howard put me on staff, and I soaked up everything he had to teach me. Not just his advice about writing humor, which was: “Don’t bore me, okay?” but also how he deftly seduced and manipulated his staff so that we behaved the way he wanted us to. At first I thought it was wrong to be so manipulative. The very word conjures up self-serving evil, but I think there are many kinds of manipulation. The most common kind is really very normal: It’s an instinct embedded in our DNA. Aren’t we born trying to control our universe from our first breath of life? What do you think all that crying is about when we slip out of the womb?

You are probably a master manipulator already and you don’t even know it. When you were just days old, you were already controlling your poor mother. You quickly learned that if you wail, your mother springs into action with a whole repertoire of services for your personal pleasure. You cry and she picks you up. Or she feeds you, changes your diaper, or just cuddles with you until you feel better. She’s thrilled when you stop crying. It didn’t take you long to put this together. What power you had over her.

When you were just eight months old, you lowered your eyes and looked at your father through your lashes. You have already wrapped the guy around your tiny finger, and he will stay there until your hormones kick in at around thirteen and you become a temporary monster.

Then you’re a mother yourself and the chickens come home to roost. Your seven-year-old son wants a video iPod. You say he’s too young. He says all the other kids in his class have one. You say you don’t care. He says he will carry out the garbage every night until he goes to college. You say . . . And, he continues, he will never wash his little sister’s dolls and dry them in the microwave ever again. He will be nice to her in perpetuity. You ask if he knows what that word means. He says “until the end of time.” He looked it up on www.dictionary.com.

You get him the iPod.

The most successful people in business, warfare, politics, and life itself are masters of the art of manipulation. The really good ones, like Howard, are masters of seduction and manipulation, or S&M as I like to call it. This combination is a psychological powerhouse, but in order for it to work, the two skills have to be inextricably linked. Manipulation without seduction breeds only contempt and resentment. Seduction without manipulation may be fun for a while, but it doesn’t get you anywhere except in trouble. People who use their skills at S&M for their own selfish reasons deserve to be held in contempt. The ones who do it for a higher cause are considered to be great leaders. If the word “manipulation” irks you, substitute “invisible persuasion.” Same thing.

After almost two years with Howard, I had written and produced hundreds of radio commercials but only one television commercial. And that experience almost turned me off to advertising before I really even got started.

We were selling a diaper service, and we had cast the most adorable nine-month-old girl as The Baby. The problem was that this baby was too happy. She loved the cameras and the lights, and everything made her giggle and gurgle with delight. I was crazy about this kid, and whenever we had a break, I held her and played with her. But there was one scene where she was supposed to cry because her diaper was wet.

“Let’s just wait until she gets tired, then she’ll cry, right?” I said to the mother. But the mother just shook her head sadly. This was her very first television commercial, and she didn’t know enough to lie.

“She never cries,” the mother said in disgust.

“She never cries?” the director, lighting guy, and I asked in unison.

“Never.”

The lighting guy started shutting down the lights.

“No, wait,” the mother said.

Then she picked up her beautiful baby girl and bit her on the leg. The baby wailed. The lights went back on. We shot the scene. Nobody seemed to mind, but I have never forgotten the look of betrayal on that baby’s face when her own mother hurt her—for a lousy commercial.

My first reaction was that I needed to get out of this business. But then I talked myself out of it. I liked advertising; I just didn’t like that part of it. Maybe if I went to another agency, a bigger shop with a good creative reputation, things like this wouldn’t happen. People wouldn’t bite little babies to get a scene shot. That wishful thinking, along with the certainty that I would never get ahead in advertising writing radio commercials for retail stores in Cleveland, Ohio, lit a fire under me.

Right around this time, a young, ambitious creative director named Bill Westbrook had been trying to recruit me for his agency in Richmond, Virginia, a prestigious, regional shop called Cargill, Wilson & Acree. I had met Bill while I was being a dutiful wife to my first husband, the dour actor. At the very beginning of our marriage, my husband had been drafted and sent to Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, and I followed him. There I met Bill at a small agency called Newman, Saylor & Gregory. They needed an assistant art director. I lied about having the skills they needed (making Photostats on a cameralike machine, primarily), and they hired me. I couldn’t art direct my way out of a paper sack, and I kept jamming the Photostat machines I was supposed to be an expert at running. I’d never even seen one before. After the third repairman came, I begged him to teach me how to make stats without causing a crisis, and I got pretty good at it. Even so, Bill knew me for the fraud I was as an art director and kept slipping me ads to write. He always thought I could be good, and when he became the creative director at Cargill several years later, he tried to hire me. He tried to hire me for two years.

But leaving New York permanently and moving to the South was a big step for an unsophisticated Italian American from Brooklyn who had been on an airplane only once. I was scared. Bill was persistent, though, and I finally consented. I had nothing to lose. I was thirty years old and desperate, and sometimes desperation can give even a coward the semblance of a backbone.

From the Hardcover edition.

My Life Started in an Elevator

I wasn’t actually born in an elevator. Or conceived in one. (How freaky would that be? Can you imagine your parents doing it in an elevator?) My career started in an elevator, and that was the beginning of my real life, the one I don’t look back on and shudder at. It happened one Saturday morning in May. I was with my first husband, a crabby actor I had married four years earlier because I thought I could cheer him up. We had just left our sixth-floor Manhattan apartment to go grocery shopping and, when the elevator doors closed, my husband announced that he had made a decision. I thought he’d decided what he wanted for dinner.

No. He had come to the conclusion that he didn’t love me anymore.

When we reached the fourth floor he said that, upon reflection, he probably never had.

By the time we got to the lobby, he confessed that he was in love with another woman.

His entire revelation took less than sixty seconds. Then we went shopping for food. I bought a nice eye-of-round roast. It was on sale. I even cooked it for the little shit.

A week later he packed up and left, and I sprang into action. I painted the bedroom an insomnia-inducing shade of bubble gum pink because he’d never let me decorate our apartment the way I wanted and I needed to assure myself that I was in control of my life. It made me feel like I was sleeping in a giant lung, but I didn’t care. It was my lung now and I could do with it what I wanted. Then I stopped eating the junk food that was a substitute for you-know-what and lost thirty-five pounds in six months. (Isn’t that great?) And I quit my job writing resort ads for the Catskills (“Shecky Greene! Here thru Labor Day!”), because I realized I was not going to have a family anytime soon and I needed to think seriously about a career.

Oh, and during those first six months, when I was losing all that weight, I also wept. (I wonder how much of the thirty-five pounds had been water retention.) I cried all the time. Not because I missed my unfaithful husband, but because I felt abandoned, defeated, and convinced that no one would ever love me or even like me. I had no career, no future, and no one to blame.

I was twenty-eight.

Not a very promising beginning on the road to chairman.

I had two big “aha”s after being dumped on that elevator: First, being with the wrong man is worse than having no man at all, and second, I was totally unprepared for a career because I wasn’t good at anything. I had to change that quickly and become skilled at something of value. Luckily, I thought I could write. But I had a long road ahead of me, and I had wasted six precious years on a dead-end relationship. (We dated two years before the wedding. You’d think I would have caught on sooner.)

After I got tired of feeling sorry for myself (right around the time my body went from a size 14 to an 8), I found a job as a copywriter at Howard Marks Advertising in New York. Unlike the job writing resort ads for the Catskills, this one required talent. I had to find some of that and fast.

I was hired as a temporary employee after a thirty-minute interview with Howard Marks himself. He didn’t need much more time than that to see that I was wounded, insecure, and needy—the three traits he loved the most in another person. It turned out that Howard collected damaged souls. It provided him with built-in dedication from his employees and, to be fair, he also liked to save lives. He certainly didn’t hire me for the brilliance of my Catskills resort ads.

All Howard wanted from me was unconditional loyalty and funny radio commercials for the retail clients he served in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. Places like the local Arby’s franchise and Cleveland Tux Rentals. I was positive that I could be funny—if I could just stop crying.

Working for Howard was my first experience being in the power of a controlling person. He combined skillful manipulation with a sprinkling of child psychology and a pinch of positive reinforcement. I watched a master control me in the same way he controlled all the people who worked for him. I saw him get better work from us all without really asking for it. He did it by making us desperate for his approval and by keeping us off balance. We never knew when the happy, charming Howard would show up for work or when the mean, irritable Mr. Marks would be joining us for a verbal whipping. I think this was more a result of his blood-sugar levels than any psychological issue. He was always on a diet and believed he could eat as much as he wanted if the foods were low in fat. He would eat mounds of steamed shrimp for lunch and point to his overflowing plate and say gleefully, “No calories!” Looking back, I’m sure he had high cholesterol as well as diabetes.

In his more lucid moments, Howard wished for creative nirvana.

“If I could only convince people to be more creative,” he told me once, “I would be rich.”

Howard couldn’t enforce creativity, but he could give us enough confidence to open up our minds and release any dormant brilliance lurking inside.

He also taught me that you couldn’t legislate loyalty. Howard knew how to make us want to please him, especially on the days we were confident he wouldn’t fire us all in a fit of fury. Here’s how he seduced and manipulated me: Howard would give me an assignment to write a radio script. I’d write something and drop it in his in-box for approval. Then he would return it with his comments and the reason he rejected it. (There was only one reason: “Not funny!”) After a few misses, I finally got a script with “Good.” written in the upper-right-hand corner. I was really pleased. When I showed the script to the people on his staff, they kindly explained his code to me. “Good.” with a period meant it was just okay and he could live with it. It was up to me to decide whether I could live with it. “Good!” with an exclamation point meant he liked it. After that, they said, his comments were self-explanatory.

The first time I got a “Good!” from Howard I felt great! But I wanted his approval so much that I would try to do even better. When a script finally came back with “GREAT!” written in the upper corner, I was elated. That spurred me on to take bigger chances, and with my confidence growing, I would dash out scripts that actually brought a smile to my own miserable face. After a while, I got the greatest compliment Howard could give: A script came back to me with “BRILLIANT!!!” scribbled at the top.

Yes, I thought, I was brilliant. It was a radio spot for Cleveland Tux about a hapless groom who forgot he was getting married until the day before the wedding. His friends urged him to go to Cleveland Tux because he could get fitted quickly, and if his fiancée killed him, he could always use the tux for his funeral. “It’s a win-win situation,” his best man assured him.

At the end of my thirty-day trial period, Howard put me on staff, and I soaked up everything he had to teach me. Not just his advice about writing humor, which was: “Don’t bore me, okay?” but also how he deftly seduced and manipulated his staff so that we behaved the way he wanted us to. At first I thought it was wrong to be so manipulative. The very word conjures up self-serving evil, but I think there are many kinds of manipulation. The most common kind is really very normal: It’s an instinct embedded in our DNA. Aren’t we born trying to control our universe from our first breath of life? What do you think all that crying is about when we slip out of the womb?

You are probably a master manipulator already and you don’t even know it. When you were just days old, you were already controlling your poor mother. You quickly learned that if you wail, your mother springs into action with a whole repertoire of services for your personal pleasure. You cry and she picks you up. Or she feeds you, changes your diaper, or just cuddles with you until you feel better. She’s thrilled when you stop crying. It didn’t take you long to put this together. What power you had over her.

When you were just eight months old, you lowered your eyes and looked at your father through your lashes. You have already wrapped the guy around your tiny finger, and he will stay there until your hormones kick in at around thirteen and you become a temporary monster.

Then you’re a mother yourself and the chickens come home to roost. Your seven-year-old son wants a video iPod. You say he’s too young. He says all the other kids in his class have one. You say you don’t care. He says he will carry out the garbage every night until he goes to college. You say . . . And, he continues, he will never wash his little sister’s dolls and dry them in the microwave ever again. He will be nice to her in perpetuity. You ask if he knows what that word means. He says “until the end of time.” He looked it up on www.dictionary.com.

You get him the iPod.

The most successful people in business, warfare, politics, and life itself are masters of the art of manipulation. The really good ones, like Howard, are masters of seduction and manipulation, or S&M as I like to call it. This combination is a psychological powerhouse, but in order for it to work, the two skills have to be inextricably linked. Manipulation without seduction breeds only contempt and resentment. Seduction without manipulation may be fun for a while, but it doesn’t get you anywhere except in trouble. People who use their skills at S&M for their own selfish reasons deserve to be held in contempt. The ones who do it for a higher cause are considered to be great leaders. If the word “manipulation” irks you, substitute “invisible persuasion.” Same thing.

After almost two years with Howard, I had written and produced hundreds of radio commercials but only one television commercial. And that experience almost turned me off to advertising before I really even got started.

We were selling a diaper service, and we had cast the most adorable nine-month-old girl as The Baby. The problem was that this baby was too happy. She loved the cameras and the lights, and everything made her giggle and gurgle with delight. I was crazy about this kid, and whenever we had a break, I held her and played with her. But there was one scene where she was supposed to cry because her diaper was wet.

“Let’s just wait until she gets tired, then she’ll cry, right?” I said to the mother. But the mother just shook her head sadly. This was her very first television commercial, and she didn’t know enough to lie.

“She never cries,” the mother said in disgust.

“She never cries?” the director, lighting guy, and I asked in unison.

“Never.”

The lighting guy started shutting down the lights.

“No, wait,” the mother said.

Then she picked up her beautiful baby girl and bit her on the leg. The baby wailed. The lights went back on. We shot the scene. Nobody seemed to mind, but I have never forgotten the look of betrayal on that baby’s face when her own mother hurt her—for a lousy commercial.

My first reaction was that I needed to get out of this business. But then I talked myself out of it. I liked advertising; I just didn’t like that part of it. Maybe if I went to another agency, a bigger shop with a good creative reputation, things like this wouldn’t happen. People wouldn’t bite little babies to get a scene shot. That wishful thinking, along with the certainty that I would never get ahead in advertising writing radio commercials for retail stores in Cleveland, Ohio, lit a fire under me.

Right around this time, a young, ambitious creative director named Bill Westbrook had been trying to recruit me for his agency in Richmond, Virginia, a prestigious, regional shop called Cargill, Wilson & Acree. I had met Bill while I was being a dutiful wife to my first husband, the dour actor. At the very beginning of our marriage, my husband had been drafted and sent to Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, and I followed him. There I met Bill at a small agency called Newman, Saylor & Gregory. They needed an assistant art director. I lied about having the skills they needed (making Photostats on a cameralike machine, primarily), and they hired me. I couldn’t art direct my way out of a paper sack, and I kept jamming the Photostat machines I was supposed to be an expert at running. I’d never even seen one before. After the third repairman came, I begged him to teach me how to make stats without causing a crisis, and I got pretty good at it. Even so, Bill knew me for the fraud I was as an art director and kept slipping me ads to write. He always thought I could be good, and when he became the creative director at Cargill several years later, he tried to hire me. He tried to hire me for two years.

But leaving New York permanently and moving to the South was a big step for an unsophisticated Italian American from Brooklyn who had been on an airplane only once. I was scared. Bill was persistent, though, and I finally consented. I had nothing to lose. I was thirty years old and desperate, and sometimes desperation can give even a coward the semblance of a backbone.

From the Hardcover edition.