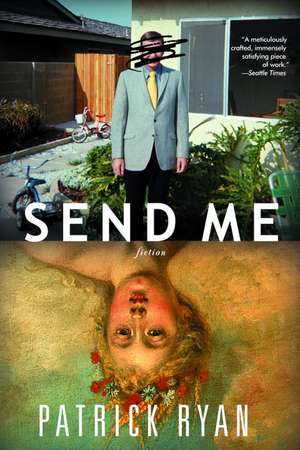

Send Me

Autor Patrick Ryanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

In the Florida of NASA launches, ranch houses, and sudden hurricanes, Teresa Kerrigan, ungrounded by two divorces, tries to hold her life together. But her ex-husbands linger in the background while her four children spin away to their own separate futures, each carrying the baggage of a complex family history. Matt serves as caretaker to the ailing father who abandoned him as a child, while his wild teenage sister, Karen, hides herself in marriage to a born-again salesman. Joe, a perpetual outsider, struggles with a private sibling rivalry that nearly derails him. And then there’s the youngest, Frankie, an endearing, eccentric sci-fi freak who’s been searching since childhood for intelligent life in the universe–and finds it.

Written with wry affection, and with compassion for every character in its pages, Send Me is a wholly original, haunting evocation of family love, loss, and, ultimately, forgiveness.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 134.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 202

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.80€ • 26.94$ • 21.35£

25.80€ • 26.94$ • 21.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385338752

ISBN-10: 0385338759

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 141 x 209 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Dial Press

ISBN-10: 0385338759

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 141 x 209 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Dial Press

Notă biografică

Patrick Ryan was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Florida. His work has appeared in the Yale Review, the Iowa Review, One Story, and other journals. He lives in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Send Me

1996

Somewhere between Rome and Dixie, he fell asleep behind the wheel. This had happened to his father once, long before Frankie was born: he'd drifted off just outside Grand Rapids, Michigan, and when he'd opened his eyes, his car was somersaulting out of a ditch and across a field, the view through the broken windshield a rapid slide show of sky, grass, sky, grass, sky, grass. One of the doors came off. The backseat was torn loose and expelled. The bumpers, the hubcaps, the headlight rings, the trunk lid, and the jack shot out like shrapnel from a grenade. When the car finally came to rest on its wheels over fifty yards from the highway, it was so mangled that the state trooper who arrived on the scene was unable to make a visual identification of the vehicle's year, make, or model. These details were learned from the young man sitting behind the wheel, dazed and disoriented, but with nothing more than a bruised elbow and a superficial cut on his forehead. "It's a miracle of God," the trooper had said, but Frankie's mother, deserted by two husbands by the time she told him the story, had footnoted the remark: "More like dumb luck."

Frankie's luck--dumb or otherwise--held him steady as he dozed. When his head snapped upright and his mind pulled out of what had seemed like a long stretch of darkness, he found an early afternoon intensely radiant with greens and blues. He was on a road in the Conecuh National Forest of Alabama, both hands on the wheel, and he was centered perfectly in his lane.

The road turned into a bridge, and the Volkswagen skimmed a level path across the river, like a hovercraft. Then the bridge turned back into a road. The trees began to thin out. He saw a sign for Damascus, then another, smaller sign made of two flat wooden triangles nailed to a post. The triangles were painted white and bore words so small that Frankie had to come to a full stop and lean into the windshield to read them.

Turn

Here for

The Gallery of

The Eleventh Coming

said the top one, and beneath it:

Rev.

Damien Lee

Wheeler

(Every-Thing Seen Is for Sale.)

Just in front of the sign stood a mailbox with a number that matched the one on Frankie's Rolodex card. He steered the Volkswagen along the dirt road that led into the marsh.

He'd sketched a road just like this recently. Smears of brown pastel rose on one side of it, snakes of blue pencil reaching across a green plain on the other. But in the sketch there'd been a church as large as an airplane hangar, made entirely of polished steel, and all he saw when he rounded the bend in the dirt road was a small, salmon-colored shack of a house.

It sat on cinder blocks in the middle of a clearing of damp grass. The clearing was fronted by a thick wire strung waist high between a series of fence posts and hung with wooden placards that nearly reached the ground: calendars, he noticed as he pulled up alongside them, each one heavily illustrated. When he shut off the engine, a kinetic silence rose from the ground and hummed against his ears, hindered only by the sound of a cicada, and then shattered completely by the shriek of a screen door.

At the top of three bowed steps, a man stood in an open red bathrobe, a V-neck undershirt, dark slacks, and a pair of hunting boots. His fingertips beneath the cuffs of the robe, his exposed wedge of chest, his neck and face--all were a deep, rich brown. His bald scalp reflected the sun as if his skull were a light source. He was staring at Frankie behind the wheel of the Volkswagen.

He looked livid.

Frankie got out of the car. He stood holding his keys with both hands, dodging the angry gaze by studying the calendars strung along the wire.

"Have you been sent?" the Reverend asked in a voice so low that he seemed to be speaking through a cardboard tube.

"Yes," Frankie said. A gallery owner in Jacksonville had introduced him to the Reverend's work, showing him several original pieces, and slides of a dozen more. But then he added "No," because the owner had refused to give him the Reverend's address, and when she'd left the room, he'd swiped it from her Rolodex.

"You're not sure which one?"

Frankie shrugged. "Maybe both."

"I understand." The Reverend descended the steps carefully and crossed the lawn. "More and more citizens arrive all the time. Three last month alone. Some folks are sent by art dealers too sneaky to do their own buying; some just show up, no idea on Earth why they're here." When he reached the other side of the wire, he made a flourish with his hand to indicate the row of calendars. "Everything seen is for sale. Of course, I'd be a liar if I said the sent ones weren't preferred. No wisdom for fools; I know what butters bread. Which is why all of my prices are not negotiable but reasonable. And that's generous, because this is not a reasonable world. You look like someone who knows that."

Frankie had stepped back from the wire at the Reverend's approach. He glanced at the hunting boots, the sides of which were coated with mud. When he looked up, he saw the Reverend studying him. The man's head was a sieve of perspiration. Where his eyes--bulbous, thyroidal--should have been white, they were yellow clouded with pink: spheres of amniotic fluid that had allowed his pupils to evolve into the receptors that now scanned rapidly over every part of Frankie's body, collecting information. Frankie felt as if he were being x-rayed. Then the Reverend dipped a hand into a pocket in his terry cloth robe and brought a folded handkerchief to his face. He passed it over his eyes. "I'm the Reverend."

"Frankie Kerrigan," Frankie said. "Where's your church?"

The hand that held the handkerchief lifted above his head, and with a long finger he drew a horizontal circle in the air, seeming to indicate the entire sky. "The sent ones come from Atlanta, mostly. Some come from Savannah, or Charlotte. Never west, always east. I got a letter some time back, an art dealer up in New York City wanted a price list. At least she was honest enough to say what she was. I used her paper and sent her back a vision--with the list. I called it 'Twenty Johns and a Whore Are Not Selected.' "

"I saw your work in a gallery in Jacksonville," Frankie offered. He bent his legs against the ache in his knees.

"So you were sent."

"Not really. I just saw your work and . . . decided to come."

The Reverend dragged the handkerchief across the dome of his head. "You might start at the beginning," he suggested, nodding toward the far end of the row of calendars.

Frankie walked down one side of the wire; the Reverend walked down the other. The first placard, Frankie now noticed, wasn't a calendar but a painting of an open white hand against a grid, with orange flames on the tips of each finger. On the palm was a dollar sign. Above it, in green, were the words "Five Dollars Payable for Viewing." He glanced up and saw one of the Reverend's hands extended toward him, palm up.

"Thank you," the Reverend said, once Frankie had dug the bill out of his wallet. "I'll let you be for a while." He stuffed the money into a pocket as he turned away, and walked back toward the house.

Each calendar was laid out traditionally, with the illustration above and the grid for the month below. But the first month was called Normalary, and the days, unnumbered, were peppered with notes: "Been good to dear Lila," "Been a good man," "Still good," "Love my dear Lila." Frankie had seen a similar calendar in Jacksonville. It had been called Lovepril, and had been filled with acknowledgments of having been a good husband. The illustration had depicted, in a pointillist, comic-book style that adhered to no rules of proportion or perspective, a man in a blue baseball cap and a woman in a pink dress holding hands and walking in a field of spiraling colors. In Normalary, the same two people were sitting down to a picnic at the foot of a spectral mountain. A tiny spacecraft hovered in the distance in both paintings, a few minuscule daubs of gray paint that might have looked like a bird to someone unfamiliar with the Reverend's work. The next month on the fence, Betremeber, showed a rowboat on a river of colors, and in it, a bearded man holding his fists in the air while the woman in pink sank her face into his lap. In the distance the spacecraft loomed, somewhat larger now, its underside circled with blue dots. One of the notes on the unnumbered grid read "Blue Light Special!" and on the next day, "L-I-L-A: Lecherous Insipid Lies Accumulate," alongside "They knew before I did." This was followed by a month called Whorefest, and it took Frankie a moment to realize he was looking at a close-up of a vagina, surrounded by a dozen thumb-sized replicas of the bearded man's face. Several placards down was a month called You-Lie, wherein the spacecraft--larger and shaped like a Bundt cake pan with tentacles--hovered over a house much like the salmon-colored shack and emitted a beam of blue light that fanned out to the ends of the clearing. In Lawgust, the man in the blue cap was suspended in midair while the spacecraft above him projected into the swirling night sky what appeared to be a film of the oral sex in the rowboat. Dismember was an entire landscape consumed by primary-color flames. Finally, there was a month called Winter, subtitled "All Liars and Whores of Babel Are Left Behind / Good People Are Driven." The illustration showed a fleet of tentacled Bundt cake pans ascending over a charred and smoking crater. In the crater's center was a small mountain of skulls.

Frankie stepped away and counted the months. There were seventeen. He looked toward the house and saw the Reverend walking out of it, down the steps, backward. It occurred to him that he might have fallen asleep again, might have lain down on the grass next to the fence and slipped into a dream. In trying to confirm this, as he sometimes did while actually dreaming, he squinted and then forced his eyes open wide. The Reverend walked backward all the way across the yard, then turned around at the last post to face Frankie.

"What you see is just a representation."

"Oh, I--I understand that," Frankie said, glancing down at the mountain of skulls.

"I'm saying, there's more in the house." He started across the lawn--walking forward this time--and without looking back, he motioned with a finger over his shoulder for Frankie to follow.

It was a normal house inside, save for the fact that nearly every surface was illustrated. The ceiling was a map of some alternative outer space crowded with planets, many of them triangular or square. The walls were laden with paragraphs of handwritten text framed inside a network of snakes. The coffee table was a mural of an earthquake. The armchair was rendered on fire with red and orange paint that flaked off and collected around it like dandruff, and the floor itself was painted to resemble a flood, scattered with men, women, horses, and dogs, all in the process of drowning. "You might care for this." The Reverend tapped one of his boots against a stool covered with eyes.

"Thank you," Frankie said, eager to sit down.

"I mean, it's for sale," the Reverend clarified. "Everything seen is for sale. Everything unseen is either already gone, or I won't sell it. See this?" He took from one of his pockets what looked to be a perfectly round orb of naked wood no bigger than a tennis ball. "Giotto di Bondone was the only person that ever lived who could draw a perfect circle without even trying. I made this from a branch that fell on my house last summer. I made it with a kitchen knife. It's perfect, and it's for sale."

Beneath the front window, a small plastic tape deck sat on the floor, unplugged. A hammer had been smashed into the top of it, the handle jutting out like that of a hatchet sunk into a tree stump. The Reverend noticed Frankie looking at it and said, "That's a sculpture. It broke, so I turned it into a prophecy. All our machines will fail us."

A small metal fan oscillated on top of a television in the corner, stirring the warm air. Frankie's skin began to itch. He rubbed his fingertips through his hair and looked around for something to sit on that wasn't merchandise. "Why were you walking backward outside?"

"Excuse me?"

"Why were you--can I sit down somewhere?"

"Careful, now. Christmas!" the Reverend said. Frankie felt a warm hand around his upper arm. He'd nearly toppled, and was dangling now over a torrid sea. A cow was swimming for its life beneath him, trying to get a hoof onto the roof of a half-submerged barn. "Careful," the Reverend said again. "Right over here." He guided Frankie to the flaming armchair. It crackled beneath him. "Just sit. I'm going to get you a glass of water."

Frankie closed his eyes. He felt the breath of the fan across his face, heard a faucet running in the next room.

"Drink that," the Reverend said.

He opened his eyes and took the glass. The Reverend sat down on one end of the coffee table, facing him, and leaned forward to rest his elbows on his knees. His red bathrobe dipped into the floodwater around his boots.

"Tell you what I don't see--not that it matters to me one way or the other. I don't see somebody who came here to buy something."

Frankie had nearly reached the bottom of the glass. He looked over the rim at the Reverend as he drank.

"Let me ask you something, son. How old are you?"

"Twenty-nine."

"That's a hard twenty-nine. You eat anything today?"

"Breakfast," Frankie said. And then, remembering, "Lunch too."

"Where are you from, again?"

"Jacksonville. But I grew up lower down the coast, on Merritt Island. Where NASA is."

The Reverend glanced at the ceiling. "Those whores of Babel." With a thumb and forefinger, he wiped the sweat from his eyes. "The heat does catch up. It makes you slow, is how it does it. Really, now. Tell me what you're doing here."

"What's the Eleventh Coming?"

From the Hardcover edition.

1996

Somewhere between Rome and Dixie, he fell asleep behind the wheel. This had happened to his father once, long before Frankie was born: he'd drifted off just outside Grand Rapids, Michigan, and when he'd opened his eyes, his car was somersaulting out of a ditch and across a field, the view through the broken windshield a rapid slide show of sky, grass, sky, grass, sky, grass. One of the doors came off. The backseat was torn loose and expelled. The bumpers, the hubcaps, the headlight rings, the trunk lid, and the jack shot out like shrapnel from a grenade. When the car finally came to rest on its wheels over fifty yards from the highway, it was so mangled that the state trooper who arrived on the scene was unable to make a visual identification of the vehicle's year, make, or model. These details were learned from the young man sitting behind the wheel, dazed and disoriented, but with nothing more than a bruised elbow and a superficial cut on his forehead. "It's a miracle of God," the trooper had said, but Frankie's mother, deserted by two husbands by the time she told him the story, had footnoted the remark: "More like dumb luck."

Frankie's luck--dumb or otherwise--held him steady as he dozed. When his head snapped upright and his mind pulled out of what had seemed like a long stretch of darkness, he found an early afternoon intensely radiant with greens and blues. He was on a road in the Conecuh National Forest of Alabama, both hands on the wheel, and he was centered perfectly in his lane.

The road turned into a bridge, and the Volkswagen skimmed a level path across the river, like a hovercraft. Then the bridge turned back into a road. The trees began to thin out. He saw a sign for Damascus, then another, smaller sign made of two flat wooden triangles nailed to a post. The triangles were painted white and bore words so small that Frankie had to come to a full stop and lean into the windshield to read them.

Turn

Here for

The Gallery of

The Eleventh Coming

said the top one, and beneath it:

Rev.

Damien Lee

Wheeler

(Every-Thing Seen Is for Sale.)

Just in front of the sign stood a mailbox with a number that matched the one on Frankie's Rolodex card. He steered the Volkswagen along the dirt road that led into the marsh.

He'd sketched a road just like this recently. Smears of brown pastel rose on one side of it, snakes of blue pencil reaching across a green plain on the other. But in the sketch there'd been a church as large as an airplane hangar, made entirely of polished steel, and all he saw when he rounded the bend in the dirt road was a small, salmon-colored shack of a house.

It sat on cinder blocks in the middle of a clearing of damp grass. The clearing was fronted by a thick wire strung waist high between a series of fence posts and hung with wooden placards that nearly reached the ground: calendars, he noticed as he pulled up alongside them, each one heavily illustrated. When he shut off the engine, a kinetic silence rose from the ground and hummed against his ears, hindered only by the sound of a cicada, and then shattered completely by the shriek of a screen door.

At the top of three bowed steps, a man stood in an open red bathrobe, a V-neck undershirt, dark slacks, and a pair of hunting boots. His fingertips beneath the cuffs of the robe, his exposed wedge of chest, his neck and face--all were a deep, rich brown. His bald scalp reflected the sun as if his skull were a light source. He was staring at Frankie behind the wheel of the Volkswagen.

He looked livid.

Frankie got out of the car. He stood holding his keys with both hands, dodging the angry gaze by studying the calendars strung along the wire.

"Have you been sent?" the Reverend asked in a voice so low that he seemed to be speaking through a cardboard tube.

"Yes," Frankie said. A gallery owner in Jacksonville had introduced him to the Reverend's work, showing him several original pieces, and slides of a dozen more. But then he added "No," because the owner had refused to give him the Reverend's address, and when she'd left the room, he'd swiped it from her Rolodex.

"You're not sure which one?"

Frankie shrugged. "Maybe both."

"I understand." The Reverend descended the steps carefully and crossed the lawn. "More and more citizens arrive all the time. Three last month alone. Some folks are sent by art dealers too sneaky to do their own buying; some just show up, no idea on Earth why they're here." When he reached the other side of the wire, he made a flourish with his hand to indicate the row of calendars. "Everything seen is for sale. Of course, I'd be a liar if I said the sent ones weren't preferred. No wisdom for fools; I know what butters bread. Which is why all of my prices are not negotiable but reasonable. And that's generous, because this is not a reasonable world. You look like someone who knows that."

Frankie had stepped back from the wire at the Reverend's approach. He glanced at the hunting boots, the sides of which were coated with mud. When he looked up, he saw the Reverend studying him. The man's head was a sieve of perspiration. Where his eyes--bulbous, thyroidal--should have been white, they were yellow clouded with pink: spheres of amniotic fluid that had allowed his pupils to evolve into the receptors that now scanned rapidly over every part of Frankie's body, collecting information. Frankie felt as if he were being x-rayed. Then the Reverend dipped a hand into a pocket in his terry cloth robe and brought a folded handkerchief to his face. He passed it over his eyes. "I'm the Reverend."

"Frankie Kerrigan," Frankie said. "Where's your church?"

The hand that held the handkerchief lifted above his head, and with a long finger he drew a horizontal circle in the air, seeming to indicate the entire sky. "The sent ones come from Atlanta, mostly. Some come from Savannah, or Charlotte. Never west, always east. I got a letter some time back, an art dealer up in New York City wanted a price list. At least she was honest enough to say what she was. I used her paper and sent her back a vision--with the list. I called it 'Twenty Johns and a Whore Are Not Selected.' "

"I saw your work in a gallery in Jacksonville," Frankie offered. He bent his legs against the ache in his knees.

"So you were sent."

"Not really. I just saw your work and . . . decided to come."

The Reverend dragged the handkerchief across the dome of his head. "You might start at the beginning," he suggested, nodding toward the far end of the row of calendars.

Frankie walked down one side of the wire; the Reverend walked down the other. The first placard, Frankie now noticed, wasn't a calendar but a painting of an open white hand against a grid, with orange flames on the tips of each finger. On the palm was a dollar sign. Above it, in green, were the words "Five Dollars Payable for Viewing." He glanced up and saw one of the Reverend's hands extended toward him, palm up.

"Thank you," the Reverend said, once Frankie had dug the bill out of his wallet. "I'll let you be for a while." He stuffed the money into a pocket as he turned away, and walked back toward the house.

Each calendar was laid out traditionally, with the illustration above and the grid for the month below. But the first month was called Normalary, and the days, unnumbered, were peppered with notes: "Been good to dear Lila," "Been a good man," "Still good," "Love my dear Lila." Frankie had seen a similar calendar in Jacksonville. It had been called Lovepril, and had been filled with acknowledgments of having been a good husband. The illustration had depicted, in a pointillist, comic-book style that adhered to no rules of proportion or perspective, a man in a blue baseball cap and a woman in a pink dress holding hands and walking in a field of spiraling colors. In Normalary, the same two people were sitting down to a picnic at the foot of a spectral mountain. A tiny spacecraft hovered in the distance in both paintings, a few minuscule daubs of gray paint that might have looked like a bird to someone unfamiliar with the Reverend's work. The next month on the fence, Betremeber, showed a rowboat on a river of colors, and in it, a bearded man holding his fists in the air while the woman in pink sank her face into his lap. In the distance the spacecraft loomed, somewhat larger now, its underside circled with blue dots. One of the notes on the unnumbered grid read "Blue Light Special!" and on the next day, "L-I-L-A: Lecherous Insipid Lies Accumulate," alongside "They knew before I did." This was followed by a month called Whorefest, and it took Frankie a moment to realize he was looking at a close-up of a vagina, surrounded by a dozen thumb-sized replicas of the bearded man's face. Several placards down was a month called You-Lie, wherein the spacecraft--larger and shaped like a Bundt cake pan with tentacles--hovered over a house much like the salmon-colored shack and emitted a beam of blue light that fanned out to the ends of the clearing. In Lawgust, the man in the blue cap was suspended in midair while the spacecraft above him projected into the swirling night sky what appeared to be a film of the oral sex in the rowboat. Dismember was an entire landscape consumed by primary-color flames. Finally, there was a month called Winter, subtitled "All Liars and Whores of Babel Are Left Behind / Good People Are Driven." The illustration showed a fleet of tentacled Bundt cake pans ascending over a charred and smoking crater. In the crater's center was a small mountain of skulls.

Frankie stepped away and counted the months. There were seventeen. He looked toward the house and saw the Reverend walking out of it, down the steps, backward. It occurred to him that he might have fallen asleep again, might have lain down on the grass next to the fence and slipped into a dream. In trying to confirm this, as he sometimes did while actually dreaming, he squinted and then forced his eyes open wide. The Reverend walked backward all the way across the yard, then turned around at the last post to face Frankie.

"What you see is just a representation."

"Oh, I--I understand that," Frankie said, glancing down at the mountain of skulls.

"I'm saying, there's more in the house." He started across the lawn--walking forward this time--and without looking back, he motioned with a finger over his shoulder for Frankie to follow.

It was a normal house inside, save for the fact that nearly every surface was illustrated. The ceiling was a map of some alternative outer space crowded with planets, many of them triangular or square. The walls were laden with paragraphs of handwritten text framed inside a network of snakes. The coffee table was a mural of an earthquake. The armchair was rendered on fire with red and orange paint that flaked off and collected around it like dandruff, and the floor itself was painted to resemble a flood, scattered with men, women, horses, and dogs, all in the process of drowning. "You might care for this." The Reverend tapped one of his boots against a stool covered with eyes.

"Thank you," Frankie said, eager to sit down.

"I mean, it's for sale," the Reverend clarified. "Everything seen is for sale. Everything unseen is either already gone, or I won't sell it. See this?" He took from one of his pockets what looked to be a perfectly round orb of naked wood no bigger than a tennis ball. "Giotto di Bondone was the only person that ever lived who could draw a perfect circle without even trying. I made this from a branch that fell on my house last summer. I made it with a kitchen knife. It's perfect, and it's for sale."

Beneath the front window, a small plastic tape deck sat on the floor, unplugged. A hammer had been smashed into the top of it, the handle jutting out like that of a hatchet sunk into a tree stump. The Reverend noticed Frankie looking at it and said, "That's a sculpture. It broke, so I turned it into a prophecy. All our machines will fail us."

A small metal fan oscillated on top of a television in the corner, stirring the warm air. Frankie's skin began to itch. He rubbed his fingertips through his hair and looked around for something to sit on that wasn't merchandise. "Why were you walking backward outside?"

"Excuse me?"

"Why were you--can I sit down somewhere?"

"Careful, now. Christmas!" the Reverend said. Frankie felt a warm hand around his upper arm. He'd nearly toppled, and was dangling now over a torrid sea. A cow was swimming for its life beneath him, trying to get a hoof onto the roof of a half-submerged barn. "Careful," the Reverend said again. "Right over here." He guided Frankie to the flaming armchair. It crackled beneath him. "Just sit. I'm going to get you a glass of water."

Frankie closed his eyes. He felt the breath of the fan across his face, heard a faucet running in the next room.

"Drink that," the Reverend said.

He opened his eyes and took the glass. The Reverend sat down on one end of the coffee table, facing him, and leaned forward to rest his elbows on his knees. His red bathrobe dipped into the floodwater around his boots.

"Tell you what I don't see--not that it matters to me one way or the other. I don't see somebody who came here to buy something."

Frankie had nearly reached the bottom of the glass. He looked over the rim at the Reverend as he drank.

"Let me ask you something, son. How old are you?"

"Twenty-nine."

"That's a hard twenty-nine. You eat anything today?"

"Breakfast," Frankie said. And then, remembering, "Lunch too."

"Where are you from, again?"

"Jacksonville. But I grew up lower down the coast, on Merritt Island. Where NASA is."

The Reverend glanced at the ceiling. "Those whores of Babel." With a thumb and forefinger, he wiped the sweat from his eyes. "The heat does catch up. It makes you slow, is how it does it. Really, now. Tell me what you're doing here."

"What's the Eleventh Coming?"

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize Finalist, 2006