Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and Love

Autor Jennifer Keishin Armstrongen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 iun 2019

This is the story of how a columnist, two gay men, and a writers’ room full of women used their own poignant, hilarious, and humiliating stories to launch a cultural phenomenon. They endured shock, slut-shaming, and a slew of nasty reviews on their way to eventual—if still often begrudging—respect. The show wasn’t perfect, but it revolutionized television for women.

When Candace Bushnell began writing for the New York Observer, she didn’t think anyone beyond the Upper East Side would care about her adventures among the Hamptons-hopping media elite. But her struggles with singlehood struck a chord. Beverly Hills, 90210 creator Darren Star brought her vision to an even wider audience when he adapted the column for HBO. Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha launched a barrage of trends, forever branded the actresses that took on the roles, redefined women’s relationship to sex and elevated the perception of singlehood.

Featuring exclusive new interviews with the cast and writers, including star Sarah Jessica Parker, creator Darren Star, executive producer Michael Patrick King, and author Candace Bushnell, “Jennifer Keishin Armstrong brings readers inside the writers’ room and into the scribes’ lives…The writing is fizzy and funny, but she still manages an in-depth look at a show that’s been analyzed for decades, giving readers a retrospective as enjoyable as a $20 pink cocktail” (The Washington Post). Sex and the City and Us is both a critical and nostalgic behind-the-scenes look at a television series that changed the way women see themselves.

Preț: 95.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 143

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.30€ • 18.91$ • 15.23£

18.30€ • 18.91$ • 15.23£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501164835

ISBN-10: 150116483X

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 2 x 8-page 4-C inserts

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 150116483X

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 2 x 8-page 4-C inserts

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

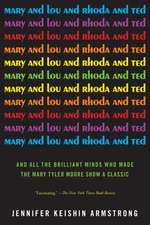

Notă biografică

Jennifer Keishin Armstrong is the author of Sex and the City and Us, Seinfeldia, and Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted. She writes about pop culture for several publications, including The New York Times Book Review, Fast Company, Vulture, BBC Culture, Entertainment Weekly, and several others. She grew up in Homer Glen, Illinois, and now lives in New York City. Visit her online at JenniferKArmstrong.com.

Extras

Sex and the City and Us

Fifteen years in Manhattan, and Candace Bushnell was as broke as ever. She had arrived in New York City from Connecticut in 1978 at age nineteen, but after a decade and a half of trying to make it there, she barely had anything in her bank account to show for it.

She did, however, have several friends. And some of them did have money. One kept two apartments, using one as a home and the other as an office, the latter in a charming art deco building at 240 East 79th Street. When Bushnell needed a place to live, her friend stepped up and offered part of her “office” as living quarters for Bushnell. The friend kept her own office in the bedroom, while Bushnell slept on a fold-out sofa and worked in the other room. Bushnell liked having her friend nearby for moral support as she wrote articles for magazines such as Mademoiselle and Esquire, as well as the “People We’re Talking About” column for Vogue.

Bushnell was still sleeping on the pull-out couch when she started freelance writing for the New York Observer, a publication distinguished by its pinkish paper and upscale readership.

Her boss, editor-in-chief Susan Morrison, who would go on to become articles editor at the New Yorker, called Bushnell the paper’s “secret weapon,” because Bushnell had a special aptitude for getting her subjects to speak candidly.

Morrison left the paper, but Bushnell stayed on as the top job was taken over by Peter Kaplan—a bespectacled journalist who would become the paper’s defining editor. One fall afternoon in 1994, Kaplan said to Bushnell, “So many people are always talking about your stories. Why don’t you write a column?” When Bushnell agreed, he asked, “What do you think it should be about?”

“I think it should be about being a single woman in New York City,” she answered, “and all the crazy things that happen to her.” She could focus on her life and her immediate circle: She was thirty-five and single, a status that was still shocking in certain segments of society, even in New York City in 1994. Several of her friends had also made it past thirty without getting married, and they would make great sources and characters.

Like many in the media, Bushnell lived an in-between-classes life: She scrounged for sustenance, attending book parties for the free food and drinks. But she also ran with the highest of the high class, big-name designers and authors, moguls who hired interior designers for their jets, and Upper East Side moms who pioneered “nanny cams” to spy on their expensive childcare providers. It was the model for the absurd lifestyle that her alter ego, Carrie Bradshaw, would make famous, balancing small paychecks with major access to glamour and wealth. That inside perspective on the high life would become a key part of the column’s appeal.

• • •

Candace Bushnell knew nothing of private jets and nannies when she first arrived in Manhattan.

In fact, she lived in almost twelve different apartments during her first year in New York City, or at least it felt that way. Candy, as her family called her—honey-blond and Marcia Brady–pretty—had come to Manhattan to make it as an actress after she dropped out of Rice University. Then she found out she was a terrible actress, so she decided to make it as a writer instead.

Thus far, however, she’d only made it as a roommate, and even that wasn’t going well.

In one apartment, on East 49th Street, which was something of a red-light district at the time, she lived with three other girls. All three wanted to be on Broadway, and, even worse, one of them was. All they did was sing when they were home; when they weren’t home, they waitressed. Worse still, the women who lived above them on the third and fourth floors were hookers with a steady string of patrons clomping through.

Bushnell did her best to ignore the chaos and focus on her career. At a club one evening, she met the owner of a small publication called Night, where she landed her first entry-level gig. The magazine had just launched in 1978 to chronicle legendary nightclubs like Studio 54 and Danceteria. Other assistant-type work followed for Bushnell at Ladies’ Home Journal (where the mix of stories in a given month might include career advice from Barbara Walters, an exposé on sexually abusive doctors, and “low-cal party” ideas) and Good Housekeeping (which favored more traditional topics such as a “Calorie Watchers Cookbook,” White House table settings, and “How Charlie’s Angels Stay So Slim”). Finally, Bushnell landed on staff as a writer at Self in an era when cover stories included “Are You Lying to Yourself about Sex?” and “12 Savvy Ways to Make More Money.” This was at least a little closer to her speed.

Throughout the ’80s, when Bushnell was in her twenties, she found ways to write about the subjects that interested her most: sex, relationships, society, clubbing, singlehood, careers, and New York City. At that point she still thought she’d like to get married and have kids. But her work reflected the times and spoke to the millions of young women who poured into big cities to seek career success and independence instead of matrimony and family life. To pursue her own big-city dreams, Bushnell braved New York at its lowest point, when the AIDS crisis ravaged lives, graffiti covered buildings and subway cars inside and out, beefy vigilantes called the Guardian Angels roamed the streets to discourage criminals, and Times Square was populated with prostitutes and peep shows.

• • •

It was the Observer column that would ultimately catapult her to the next level of her career. Bushnell and Kaplan got down to practicalities. She’d be paid $1,000 per column, which was $250 more than other columnists at the paper were paid. This, plus her Vogue checks and perks like flights to Los Angeles for assignments, added up to a decent New York lifestyle for the time, particularly given her frugal living quarters. Bushnell and Kaplan discussed the title of her new column and settled on “Sex and the City.” A perfect newspaper column title: “pithy,” as she’d later describe it. The column was headed by an illustration of a shoe, based on a strappy pair of Calvin Klein sandals Bushnell had purchased for herself on sale.

As Bushnell later wrote, she “practically skipped up Park Avenue with joy” leaving the office after Kaplan offered her the column.

But first things first: What to write about for her “Sex and the City” debut? Well, there was that sex club everyone was talking about.

• • •

One late night in 1994, Bushnell left a dinner party at the new Bowery Bar to head uptown to a sex club on 27th Street. She didn’t know what would happen, but hoped it would be enough to fill her new column. As it turned out, Le Trapeze was, like most sexual escapades, neither as good nor as bad as imagined. It cost eighty-five dollars to enter, cash, no receipt. (Her expense reports were about to get interesting.) The presence of a hot-and-cold buffet took her aback. “You must have your lower torso covered to eat,” said a sign above. Bushnell spied “a few blobby couples” having sex on a large air mattress in the center of the room. And, as Bushnell wrote, “many men . . . appeared to be having trouble keeping up their end of the bargain.” A woman sat next to a Jacuzzi in a robe, smoking.

This experience became Bushnell’s first “Sex and the City” column, published on November 28, 1994, with the headline “Swingin’ Sex? I Don’t Think So.” Despite the come-on of the column’s name, it contained a traditional and wholesome bottom line: “I had learned that when it comes to sex, there’s no place like home.” Over the next two years, Bushnell would chronicle the gulf between fantasy and reality, between what the hippest of the hip of New York City thought they should be doing and what they truly wanted in their souls. If they could find their souls.

As Bushnell wrote in that first piece: “Sex in New York is about as much like sex in America as other things in New York are. It can be annoying; it can be unsatisfying; most important, sex in New York is only rarely about sex. Most of the time it’s about spectacle, Todd Oldham dresses, Knicks tickets, the Knick [sic] themselves, or the pure terror of Not Being Alone in New York.”

Over the next two years, Bushnell would sit at her desk in her friend’s apartment on the tenth floor of the 79th Street building, writing her column. She smoked and looked out on an air shaft from the dark three-bedroom apartment as she pondered the lives and loves of those she knew and tapped away on her Dell laptop keyboard. The words she wrote would turn her from a midlevel writer into a New York celebrity.

Her column gained such notoriety, in fact, that it affected her love life. High-powered men she met told her, “I thought about dating you, but now I won’t because I don’t want to end up in your column.” She would think, You aren’t interesting enough to write about anyway. Her on-again, off-again boyfriend, Vogue publisher Ron Galotti—a tanned man with slicked-back hair and a penchant for gray suits with pocket squares—did make the column regularly, referred to as “Mr. Big.” When she’d finish writing a column and show it to him, he would read her copy and issue his version of a compliment: “Cute, baby, cute.”

• • •

Bushnell never envisioned a mass audience for her work in the Observer. She never would have believed, at the time, that it would turn into a TV hit that all of America—much less the world—embraced. She only hoped to hook the select, in-the-know audience the Observer was known for, the upper echelons of high society. Bushnell’s “Sex and the City” column emphasizes opportunistic women on the hunt for financial salvation in Manhattan’s high-rolling men; her “Carrie Bradshaw”—a pseudonym for Bushnell herself—is unhinged and depressed; her friends have given up on the idea of love and connection. The result resembles a female version of Bright Lights, Big City and, in fact, the author of that book was her friend and frequent party mate Jay McInerney, whose wavy crest of dark hair, thick eyebrows, and natty style made him look more like a matinee idol than a novelist. Even McInerney, the chronicler of New York’s party culture of the coke-fueled ’80s, cracked that Bushnell “was doing advanced postgraduate work in the subject of going out on the town.”

She went out nearly every night, interviewed people at her central downtown hangout, Bowery Bar, and found stories all across town. New York was, Bushnell says, a “tight place then. It was the day when restaurants were theater. Nobody cared about the food. You just saw who was coming in, who talked to who.” If you wanted to know what was going on somewhere, you had to go there.

New York dating rituals still hearkened back to another era, “like in Edith Wharton’s time,” Bushnell says. “There were hierarchies. Society was important, the idea of wanting to be in society.” Women still often felt as if they had to please men, like Wharton wrote in The House of Mirth of her character Lily Bart: “She had been bored all the afternoon by Percy Gryce—the mere thought seemed to waken an echo of his droning voice—but she could not ignore him on the morrow, she must follow up her success, must submit to more boredom, must be ready with fresh compliances and adaptabilities.”

With the column, Bushnell had made herself into a professional dater. She got her material from dating, and she could use her profession to meet potential dates. This linked her to the city’s earliest recognized wave of professional, single women: the shopgirls of the early 1900s. They made their living as retail clerks, but more important they were single girls whose jobs gave them access to wealthy men: “Shopgirls knew that dressing and speaking the right ways would help them get a job, and that the right job could help them get a man,” Moira Weigel wrote in her history of courtship, Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating.

Bushnell and her friends had become the modern version of Edith Wharton heroines and those shopgirls, stuck between dependence on men and modern dating practices that lacked manners and rules. She envisioned herself writing for this select subculture, whispering their secrets to others like them, and perhaps even to the men who pursued them.

Before long, people began to buy the Observer just to read Bushnell’s column, people outside the Observer’s standard readership. Readers loved to guess the real identities of Bushnell’s pseudonymed characters. It was said that the writer “River Wilde” was probably Bret Easton Ellis, the American Psycho author. “Gregory Roque” was most likely Oliver Stone, the Natural Born Killers filmmaker. A Bushnell pseudonym became a status symbol of the time.

Soon everyone in town knew that Mr. Big was Galotti, the magazine publisher who drove a Ferrari and had dated supermodel Janice Dickinson. In the column, Bushnell, as a first-person narrator, introduces Mr. Big’s paramour, Carrie Bradshaw, as her “friend.” Eventually, detailed depictions of Carrie’s life—her thoughts, her word-for-word conversations, her sexual escapades—overtake the column. That, plus their shared initials, made it hard to imagine Carrie wasn’t Candace. In fact, Bushnell later revealed she’d created Carrie so her parents wouldn’t know—at least for sure—that they were reading about their daughter’s own sex life.

Readers took in every word. They read it on the subway and on the way out to the Hamptons. They delighted in Bushnell’s dissections of city types such as “psycho moms,” “bicycle boys,” “international crazy girls,” “modelizers,” and “toxic bachelors,” and they devoured the knowing insider commentary:

“It all started the way it always does: innocently enough.”

“On a recent afternoon, seven women gathered in Manhattan over wine, cheese, and cigarettes, to animatedly discuss the one thing they had in common: a man.”

“The pilgrimage to the newly suburbanized friend is one that most Manhattan women have made, and few truly enjoyed.”

“On a recent afternoon, four women met at an Upper East Side restaurant to discuss what it’s like to be an extremely beautiful young woman in New York City.”

“There are worse things than being thirty-five, single, and female in New York. Like: Being twenty-five, single, and female in New York.”

Bushnell’s column contained seedlings of the fantasy life that would bloom in Sex and the City the television show. But “Sex and the City,” as a column, was a bait and switch. The clothes command high prices and the parties attract big names; however, despite the column’s name, there isn’t much sexy sex and there’s almost no romance. One character sums it up: “I have no sex and no romance. Who needs it? No fear of disease, psychopaths, or stalkers. Why not just be with your friends?” Bushnell puts it this way: “Relationships in New York are about detachment.” The writer herself had soured on marriage, telling the New York Times it was an institution that favored men. She’d once been engaged, about four years before the launch of her column, and the experience had made her feel as if she were, she said, “drowning.”

Despite the column’s cynical soul, despite Bushnell’s personal connection with novelist friends Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis, she knew how her writing—because it was about women and feelings—was perceived.

“It’s cute. It’s light. . . . It’s not Tolstoy,” is how her friend Samantha describes Carrie’s work in one of the columns. Carrie insists that she’s not trying to be Tolstoy. Bushnell concludes, “But, of course, she was.”

Bushnell’s column fit into a long tradition of literary fascination with single women’s lives. The title of the column, in fact, referenced the most famous of them all: Helen Gurley Brown’s 1962 sensation Sex and the Single Girl. While women have never been published with the same frequency as their white male counterparts, they have proven throughout history that there was a surefire way to get attention: by explaining their exotic lives as single, independent creatures to the masses. How on earth did they survive without men? Was it as awful as it sounded? Was it as fun?

This phenomenon dated back at least as far as 1898, when Neith Boyce wrote a column for Vogue called “The Bachelor Girl.” “The day it became evident that I was irretrievably committed to this alternative lifestyle was a solemn one in the family circle,” Boyce wrote. “I was about to leave that domestic haven, heaven only knew for what port. I was going to New York to earn my own bread and butter and to live alone.”

With “Sex and the City,” Bushnell combined two historically popular column genres: the confessions of a single professional woman and the documentation of high society’s charity events, fashion, fancy homes, and gossip. She offered a juicier version of the age-old society pages.

Given this winning combination, the book publishing world inevitably pursued Bushnell. Atlantic Monthly Press released a collection of Bushnell’s columns in hardcover in August 1996. As she toured college campuses to promote the book, she noticed something unexpected: The column resonated far beyond Manhattan, far beyond its outer boroughs . . . and far beyond even the Tri-State Area. Women in Chicago, Los Angeles, and other cities throughout the nation saw their own lives in Sex and the City. They had their own Mr. Bigs; they were their own Carrie Bradshaws. “We thought people could only be this terrible in New York,” Bushnell says. “But this phenomenon of thirty-something women dating was much more universal than we thought.” She wasn’t just reporting on high society for in-the-know Manhattanites; she had become the new Holly Golightly, the glamorous single woman her college fans hoped to be someday.

The book represented an unquestionable pinnacle for Bushnell’s career. She had chased exactly this kind of fantasy from the Connecticut suburbs to New York City in 1978 with no connections, no Ivy League degree, and no money, then worked her way up the media ladder.

Reviews for the book, however, ran lukewarm. The Washington Post called it “mildly amusing,” then used most of the review to take aim at the Observer, “a singularly peculiar weekly newspaper that is printed on colored paper and edited with only two circulation areas in mind: chic Manhattan and drop-dead Hamptons.” The book, the review said, did nothing more than collate several of Bushnell’s columns, “presumably for the convenience of those who do not have their copies of the Observer bound by Madison Avenue leather crafters.”

Some reviewers mustered up more respect, like Sandra Tsing Loh in the Los Angeles Times, who compared Bushnell’s view of New York City to those of some of Bushnell’s friends, influential members of the ’80s “literary Brat Pack” such as Jay McInerney and Tama Janowitz. A Publishers Weekly review noted the “opulent debasement that suffuses this collection” and called it “brain candy”—emphasis on the “brain” as much as the “candy.”

The “candy,” however, took over as the main public perception of Sex and the City as a book. Sex and the City’s publication coincided with the introduction of another memorable thirtysomething singleton into the literary landscape: British columnist Helen Fielding’s hapless Bridget Jones. Comparisons flourished, and did nothing to boost Sex and the City’s respectability. Alex Kuczynski in the New York Times described Bridget’s obsession with men as “perfectly normal behavior, if you’re a 13-year-old girl,” then acknowledged that Bridget “makes some women laugh in sad recognition.”

In the Village Voice Meghan Daum wrote that Bridget Jones “concerns itself almost entirely with the neurotic fallout of popular women’s culture. . . . Bridget’s constant failure to follow through on even the most basic lifestyle tips offered up by her mentor, Cosmo culture, will undoubtedly provoke the disapproval of those who remain devoted to that culture’s major tenet, that self-improvement and positive thinking are synonymous with substance.”

With the exception of that last one, these reviews seemed oblivious to Bridget’s satirical nature, the fact that she and her creator were in on the joke. But Bridget and Carrie did not belong together in any sense, even though they kept getting stuck together in trend pieces. Kuczynski’s New York Times piece quotes Bushnell criticizing Bridget as “ten years out of date.” Bridget struggled with her weight and suffered from low self-esteem, but also seemed to like her life, her friends, her family, and her middle-class status. Carrie, on the other hand, knew how attractive and thin she was, dated and drank with the upper echelons of Manhattan society, and was still moody and cynical. Where Bridget was sweet and well-adjusted underneath her snark and borderline alcoholism, Carrie suffered mood swings and self-sabotaging behavior. In short, they sat at opposite ends of the single-woman character spectrum: Bridget an updated version of the single woman who knows her place, and thus is quite likable; Carrie an unsympathetic character, a true antiheroine at a time when unlikable lead female characters were rare. “I don’t write books because I want everyone to like the characters,” Bushnell says. “These are women who make some choices that maybe aren’t the best choices in terms of morality.”

With Carrie, Bushnell was going more for a Dorothy Parker type or Edith Wharton heroine than the lead of a romantic comedy, but she and Fielding were linked in the cultural ether and credited with—or blamed for—the advent of a new, much-derided book category equivalent of the rom-com: chick lit.

• • •

Whatever the perception of “Sex and the City,” it was popular. So popular, in fact, that starting about three months into the column’s run, enamored New Yorkers in the media business began faxing copies of it to their friends in the movie business in Los Angeles. Even before the collection of columns came out in book form, Bushnell began to get calls from producers eager to buy the rights for film.

TV network ABC also pursued her, particularly executive Jamie Tarses after she became president of ABC Entertainment in 1996. During her previous job at NBC, Tarses had developed Caroline in the City, Mad About You, and Friends—all New York–centric hits about young, beautiful white people. It made sense that she’d be interested in Sex and the City, which she saw as a more sophisticated, forward-thinking version of those shows. The thirty-two-year-old had just become the youngest person to run a network entertainment division at the time; she was also the first female network president ever. Industry observers were waiting for her to fail. Her new network lagged in third place of the Big Three. She needed a standout hit, and she thought a “Sex and the City” adaptation could be it.

Tarses’s thick, curly, Sarah Jessica Parker–like hair, blue eyes, and power suits would have made her look right at home on Sex and the City. Like many of the female characters, she was in her early thirties and trying to balance dating with a high-powered career. She had become a fan of Bushnell’s column and its perspective on modern relationships because she related to it. The column felt like it could become the basis of the show she had always been looking for, a voice and point of view that wasn’t already represented on television. The popularity of the column and subsequent book gave the title a recognizability that made it perfect for TV. And it appealed to the female audience ABC most wanted at the time. Tarses just had to figure out how much of the “sex” a broadcast network could allow.

As Bushnell’s star rose, the writer ran into Tarses and her boyfriend, David Letterman’s executive producer Robert Morton, in the Hamptons. Bushnell was Rollerblading when the couple pulled up next to her, as she remembers it, in a cherry-red Mercedes convertible. “Jamie wants to buy ‘Sex and the City,’?” Morton told Bushnell. “ABC’s really interested.” The pursuit was on.

But others were wooing Bushnell for the “Sex and the City” rights as well. One of Galotti’s friends, Richard Plepler—senior vice president of communications at HBO—also thought the column would be a perfect fit for his pay-cable network. Bushnell and Plepler often saw each other at the stretch of shoreline called Media Beach in the Hamptons, and every time, he’d urge her to come to a meeting at HBO.

• • •

Cable seemed like a better fit for Sex and the City, given its similarities to another book that started as a newspaper column, then became a critically acclaimed series for PBS and, later, cable network Showtime: Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. In fact, that Publishers Weekly review that called Sex and the City “brain candy” also referred to Maupin’s 1978 collection of San Francisco Chronicle columns that followed young, single people of various sexual orientations in the liberated city: “The effect is that of an Armistead Maupin–like canvas tinged with a liberal smattering of Judith Krantz,” the reviewer wrote.

Tales of the City had become a television miniseries around the same time “Sex and the City” debuted as a column; it premiered in the UK in 1993 and in the United States on PBS in 1994. The series took on issues well ahead of its time for TV, with extramarital affairs, sex, several gay love affairs, and a major transgender character. But like Sex and the City after it, Tales’ true message came down to the importance of friendship in a major metropolitan area. It also highlighted a different kind of love affair that Sex and the City would also emphasize: the relationship between a city and its denizens.

Tales couldn’t afford to be a glitzy production, however, when it came to television. Such a risky proposition meant a miniscule budget, with costumes even for its wealthiest characters coming from secondhand shops. “It was a total shoestring,” says Barbara Garrick, who played heiress DeDe Halcyon Day (and would later guest-star on Sex and the City as a spagoer who gets a happy ending from her massage therapist). “They’d hand you a dress they just bought at Goodwill.”

Tales’ frank approach to modern sexuality won it plenty of attention, both good and bad. It became the highest-rated broadcast to date on PBS at the time, but also sparked controversy as one of the few US programs to show kissing between male lovers. Attempts to produce a follow-up based on Maupin’s book series had so far failed because of the US government’s threats to pull PBS funding if it remained involved with Tales. “I did have my top off once [during the miniseries], and that went to Congress, like a pirate tape with black bars across my chest,” Garrick says. “It had all the scenes of the pot smoking and the guys kissing and the nudity.” Later, HBO rival Showtime would pick the show up for a second season.

This was the landscape into which any Sex and the City television show would take its first steps.

Just before the birth of the “Sex and the City” column, Bushnell had gone on an assignment that would change her life—and, even more, the life of her column. In fact, without this one routine assignment, the Sex and the City we know would never have come to pass.

Vogue had asked Bushnell to write a profile of Darren Star, a TV producer who had worked with Aaron Spelling to create Beverly Hills, 90210 and Melrose Place. Star had a new show on CBS, Central Park West, that transplanted his flashy, soapy approach to New York City, with Mariel Hemingway as a glamorous magazine editor and Lauren Hutton as her boss’s suspicious wife. Star was branching out on his own without Spelling, and the critics would be watching to see if Star was the real deal.

In the September 1995 piece, Bushnell follows Star—dressed “California-style” in a black Armani jacket and jeans—on a late-night visit to an S&M club called Vault, which he’s scouting for Central Park West. Star couldn’t have known at the time that it was the effect of this profile, not the show he was producing, that would resonate decades later.

Soon after the two met for the piece, Star moved to Manhattan, and Bushnell swept him into her orbit to show him around the area—for Central Park West research, of course. He had never met anyone more fun. She personified all the clichés: “A force of nature,” he says. “She opened a lot of doors.” She took him to clubs, and of course to Bowery Bar. They commemorated their friendship in ultimate Hollywood fashion: Bushnell would take the first half of her column pseudonym from Star’s nightlife columnist character on Central Park West, Carrie Fairchild, played by Mädchen Amick.

Star—a handsome gay man with brown, spiky hair—connected with Bushnell as a fellow suburban kid made good. He spent his childhood in Potomac, Maryland, a middle- to upper-class DC suburb full of politicians, ambassadors, and their families. Young Darren took film classes in high school and hoped to work in the movie industry as a writer and director. He used his bar mitzvah money to get himself a subscription to the show business trade publication Variety. While other kids partied or played sports, he made his own movies with his Super 8 camera. After graduating high school, he moved to California to study writing and film at UCLA, from which he graduated in 1983. Degree in hand, he took the classic first step toward a Hollywood career: He became a waiter.

He soon, however, got his first industry job. Star was working as a publicist for Showtime when he sold his first screenplay to Warner Bros. at age twenty-four. Doin’ Time on Planet Earth, a comedy about a teenager in Arizona who comes to believe he’s an alien prince, premiered in 1988, directed by Charles Matthau. It made little critical or commercial impact, but it helped launch Star’s career. He could now quit his job to write screenplays full-time. His next project would be If Looks Could Kill, with 21 Jump Street’s Richard Grieco as a high school French student who’s pulled into an international spy ring on a class trip.

As Star awaited that film’s release, he fulfilled a lifelong dream by moving from Los Angeles to New York City, a place whose glamour he had long admired from afar. But soon after, he got a call from Paul Stupin, a movie executive who’d just taken a job as head of drama at the new Fox television network. Stupin asked if Star would write a high school show, given his teen-oriented script experience. Stupin hoped to pair him with the much older producer Aaron Spelling (a golden TV touch who’d created 1970s hits The Love Boat and Charlie’s Angels) to create a high school series. Star thought he’d be crazy to turn down the chance to work with such a legend, which seemed like the perfect way to kill time while he waited for If Looks Could Kill to come out. So at age twenty-eight, he moved right back to Los Angeles to make a show with Spelling.

The gamble paid off. Together, Spelling and Star created a series called Beverly Hills, 90210, which followed the melodramatic lives of a group of wealthy Los Angeles teenagers. With the money Star made on the pilot, he paid cash for a Porsche. The show premiered in October 1990 to unimpressive ratings, but Fox executives decided to air the second season in the summer, when there was minimal competition for audiences. The strategy worked. Teenagers home from school for the season fell for it by the millions in July 1991. But good fortune brought with it a heavy burden: 90210’s second season would be unusually long, twenty-eight episodes instead of a standard twenty-two. Not about to fix what wasn’t broken, Fox ordered thirty the following year and thirty-two each for the next five years. This made for an insane production schedule; the 90210 staff had almost no hiatuses to break up long seasons of twelve-hour workdays.

Amid all of this, Star’s movie, If Looks Could Kill, came out in March 1991 to disappointing box office returns and reviews. In a typical review for the film, the Washington Post called it “insipid, tiresome, and full of gross kids.” But by now Star had little time to notice.

90210 became what remains the most iconic series of the teen drama genre by dealing with timely issues (date rape, drug abuse, suicide, and many others) as well as teen sex and angst-filled relationships. But Star wasn’t content to stop there. For the 1992 television season, Star created another show for Fox, the young-adult drama Melrose Place, which featured even more unapologetic sex and sensational plot lines about twentysomethings. Fox once again followed its supersized 90210 strategy and ordered thirty-two episodes of Melrose each of its first three years.

In short, Star spent the early 1990s becoming rich and successful, and working too hard to notice. The ratings numbers told him millions watched, but he rarely got the chance to see his shows’ popularity on the outside, beyond the Fox lot. Because he was in his early thirties, this streak hit at the perfect time in his life; he had energy and ambition to burn, with few other responsibilities to distract him. He’d look back on it later in life and wonder how he did it.

Bolstered by his success, he moved again to New York, this time to make a show about the city: Central Park West. He and his golden retriever, Judy Jetson, settled into a three-floor apartment owned by model-turned-restaurateur Eric Petterson. Finally living in his dream city, Star took lunches and breakfasts at 44, a restaurant known for its publishing-industry clientele, so he could get a better feel for the magazine world he planned to depict on his new series. He went to charity benefits and book parties for further research.

After meeting Candace Bushnell for that 1995 article, he had more material than he ever dreamed possible. As he hung out with Bushnell, he got to know her friends, including her paramour, Ron Galotti—a.k.a. Mr. Big. He loved to read about them in Bushnell’s new column. He admired how she mixed journalism and her own personal stories. He respected the way she exposed herself, writing about her “crazy experiences,” as he says, for the world to see.

He told Bushnell that he wanted to be the one to option the column. He thought it might make a great follow-up project to Central Park West someday.

This seemed like the answer to Bushnell’s quandary as well. She couldn’t decide whom to give it to—ABC, HBO, or a movie company. A broadcast network like ABC seemed so sanitary. HBO seemed so niche and male-centric, with its signature boxing matches and standup comedy specials. She had no idea what a movie company might do with her work.

But Star was her buddy. Star had witnessed the column’s happenings and met the people featured in it. With Star involved, she’d be able to follow how the project was proceeding.

After all of the mid-Rollerblading courtship and Media Beach cajoling she had been through, she decided this was the answer.

Reports put the price at a mere $60,000; she’ll only say it was “a little bit more.” “I wasn’t in a position [to negotiate much],” she says. “It was my first thing.”

Mediaweek reported the acquisition, quoting Star as saying Bushnell had “a unique voice that is ready to be captured and put on film.” He described her as “irreverent, vulgar, funny . . . a ’90s Dorothy Parker.” He didn’t know yet how he’d adapt the “Sex and the City” columns, which he thought were “great social satire, but too rarefied” for television. He later told the New York Times, “Only 500 people in New York know or care about that world. I needed to make it more accessible.”

But that was for later. For now, he took pride in the work he was doing for CBS on Central Park West. He had long wanted to make a glamorous show set in New York City. At the time, TV’s main vision of New York came via the grit of Law & Order. Star aimed to bring the posh world of New York media, of glossy magazines like Vanity Fair, to television audiences. He wanted viewers to have a taste of the life he’d discovered there: producing Central Park West by day, clubbing and dining with Bushnell at night.

New York City itself had entered a time of transition with the election of Rudy Giuliani as mayor in 1994. It was no longer the crime-ridden New York of the 1980s, not yet the theme park New York of the 2000s. Shifts in public life foretold the city’s future: A smoking ban in restaurants. An Old Navy discount chain store in the hip gay haven of Chelsea.

Neighborhoods were transforming faster than many residents could stand. Bowery Bar, Bushnell’s preferred hangout, battled neighborhood residents who wanted the establishment to operate under a restrictive special permit. They worried Bowery Bar would set a precedent for similar clubs, which, according to reports, “could change NoHo from a refuge for artists and light manufacturing to a trendy neighborhood flooded with late-night revelers.” The Meatpacking District was shaking off its slaughterhouse past to become a nightlife hot spot as well. A waiter at the neighborhood’s fashionable new restaurant Florent told the New York Times its customers ran the gamut, from old New Yorkers to young hipsters: “Everyone and everything, butchers, drag queens, club kids, weddings.” Many longtime New Yorkers rolled their eyes at these developments—signs, they said, that New York was over.

But the changes also indicated a shift toward a Manhattan that was more inviting to the rest of the country—that is, the majority of television viewers.

Darren Star invited columnist Candace Bushnell, author Bret Easton Ellis, and publisher Ron Galotti to his apartment on the evening of September 13, 1995, to watch a little television. The first episode of Star’s Central Park West was airing on CBS, and they would witness it as a group at Star’s posh rental near Union Square. They watched as a sultry Latin beat and crooning saxophones played over the opening credits. Mariel Hemingway, Lauren Hutton, and Michael Michele looked seductive in black-and-white images while “Created by Darren Star” flashed across the screen, signifying his first solo TV effort without Spelling.

By the time the end credits rolled, Bushnell wasn’t blown away by Central Park West, though she saw its potential. Like all of Star’s work, it was fun and glamorous. But, she says, it “missed the New Yorkiness.”

He had her to help him get a better feel for true New Yorkiness, but, as it turned out, not in time to save this series. CBS had just gotten a new president, Les Moonves, who would take the network from last place to first in the ratings—unfortunately for Star, Moonves did this by focusing on CBS’s core audience, older viewers. They were hardly the target for Central Park West, nor Star’s specialty. Central Park West lasted thirteen episodes before the network stopped production, tried to retool it, and then dumped the remaining episodes onto the schedule the following summer. Central Park West closed down for good.

Star was disappointed that his first show about New York City, and his first show without Aaron Spelling, had failed. The experience had also tried Star’s patience with big network shows that were subject to intense scrutiny, meddlesome executives, and constant pressure to produce bigger ratings. So that summer, as the remaining episodes of Central Park West aired, he started to think about how, specifically, to adapt Bushnell’s columns as an independent film. Done correctly, he thought, they could make for a great, honest movie about sex and relationships from a female perspective, with a New York sensibility. Perhaps this, instead, could be his ticket to a respectable solo career.

He liked the idea of returning to film. Though he had tried to push boundaries on 90210 and Melrose, TV overall remained, as he says, “this anachronistic space” where characters spoke in euphemisms, sex was vaguely alluded to, gay characters were rare and chaste, and nobody used dirty language. He wanted nothing to do with it anymore. Central Park West had broken him. Sex and the City could show the world he could make it without Spelling, and do so in the more prestigious world of film.

Forces began to align toward Sex and the City’s Hollywood moment with Star’s entry into the equation. But momentum pushed him back in the television direction. ABC’s Tarses and HBO both remained the show’s most enthusiastic suitors, and they could still give Star’s version of the series a TV home. Plus, Star’s name had more pull in the world of TV.

Over the summer of 1996, as Bushnell and Star Hamptons-hopped, they debated where they’d like the series to end up. Star wondered if a show could even be called Sex and the City on a major broadcast network like ABC. He didn’t know what Tarses wanted or why she wanted it, but taming the material for broadcast rules made him nervous. He didn’t want another Central Park West experience. HBO, on the other hand, seemed so New York; it was based there and would be more likely to produce the show there. Star loved his place in Manhattan and didn’t want to give it up. He also admired the one show he knew from HBO, The Larry Sanders Show.

In his meetings with HBO, Star explained to vice president of original programming Carolyn Strauss that he saw Sex and the City as a modern, R-rated version of The Mary Tyler Moore Show—a series about sex and relationships from a female point of view. This intrigued Strauss. She’d read Bushnell’s columns and was interested based on those alone—she thought Bushnell’s world would be, as she says, “a fun place to hang out” for television viewers. Strauss liked the female-centric approach, too, even though, as a gay woman, she didn’t relate to Bushnell and her man-crazy friends.

In Star’s meetings with ABC, Tarses tried to argue that her network could realize Star’s vision for the series—and, yes, the network would call the show Sex and the City. But she understood HBO’s advantage when it came to unfiltered content.

In the end, Star gave it to HBO. Its reach couldn’t match ABC’s, but at this point in his career, he longed for freedom more than commercial success. In fact, he specifically did not want commercial success. He wanted to make something special that he could be proud of.

Tarses had lost, and she understood why. Her tenure at ABC would last two more years, with a few middling new hits like Dharma & Greg, the critically adored and barely watched Sports Night, and a fizzled Fantasy Island remake. From there, she went into the production side of television, where she could create the shows she liked best; her credits would include acclaimed singles-focused comedies My Boys and Happy Endings. She wouldn’t have to spend any more time in uphill battles to compete with permissive cable networks for great shows.

Bushnell was happy with Star’s choice of HBO, which would, in fact, keep the production entirely local—with less chance of screwing up Sex and the City’s inherent New Yorkiness.

As HBO’s victory over ABC in the battle for Sex and the City demonstrated, the cable channel’s new philosophy, while it more aggressively pursued original programming, was impossible for broadcast networks to counter: HBO executives would search for series that met their own quality standards, thus ensuring that artistic merits came first. In evaluating a show, they asked whether it was good and whether it would get attention—not whether everyone in America would watch. Broadcast networks, which run on advertising dollars, had never cared about quality as much as they cared about ratings. They couldn’t, if they wanted to survive. Their business model had to prioritize commerce over art. HBO, as a channel viewers paid a premium for, didn’t have to worry as long as viewers paid. This resulted in the channel buying not only Sex and the City but also The Sopranos and Six Feet Under, and later Game of Thrones and Westworld—playing a leading role in what we would eventually call the Golden Age of Television.

Cable channels were homing in on broadcast vulnerabilities in other ways as well. TV had taken the summers off for as long as it had existed. Cable networks had noticed the weakness and scheduled new movies, series, and specials at a time when the traditional channels ran traditional reruns. By the summer of 1997, the major networks hit a new low when they attracted less than 50 percent of available viewers during the Fourth of July week. Broadcast channels scrambled to mix up their traditional slate of reruns with unseen episodes of canceled series. But HBO planned to take advantage of this network weakness by scheduling new episodes of its prison drama Oz, as well as the sports dramedy Arli$$, during the summer.

The question remained whether Sex and the City could benefit from this same strategy, even as that one pop of bright pink in the middle of HBO’s gritty, dark, predominantly male lineup.

1

The Real Carrie Bradshaw

Fifteen years in Manhattan, and Candace Bushnell was as broke as ever. She had arrived in New York City from Connecticut in 1978 at age nineteen, but after a decade and a half of trying to make it there, she barely had anything in her bank account to show for it.

She did, however, have several friends. And some of them did have money. One kept two apartments, using one as a home and the other as an office, the latter in a charming art deco building at 240 East 79th Street. When Bushnell needed a place to live, her friend stepped up and offered part of her “office” as living quarters for Bushnell. The friend kept her own office in the bedroom, while Bushnell slept on a fold-out sofa and worked in the other room. Bushnell liked having her friend nearby for moral support as she wrote articles for magazines such as Mademoiselle and Esquire, as well as the “People We’re Talking About” column for Vogue.

Bushnell was still sleeping on the pull-out couch when she started freelance writing for the New York Observer, a publication distinguished by its pinkish paper and upscale readership.

Her boss, editor-in-chief Susan Morrison, who would go on to become articles editor at the New Yorker, called Bushnell the paper’s “secret weapon,” because Bushnell had a special aptitude for getting her subjects to speak candidly.

Morrison left the paper, but Bushnell stayed on as the top job was taken over by Peter Kaplan—a bespectacled journalist who would become the paper’s defining editor. One fall afternoon in 1994, Kaplan said to Bushnell, “So many people are always talking about your stories. Why don’t you write a column?” When Bushnell agreed, he asked, “What do you think it should be about?”

“I think it should be about being a single woman in New York City,” she answered, “and all the crazy things that happen to her.” She could focus on her life and her immediate circle: She was thirty-five and single, a status that was still shocking in certain segments of society, even in New York City in 1994. Several of her friends had also made it past thirty without getting married, and they would make great sources and characters.

Like many in the media, Bushnell lived an in-between-classes life: She scrounged for sustenance, attending book parties for the free food and drinks. But she also ran with the highest of the high class, big-name designers and authors, moguls who hired interior designers for their jets, and Upper East Side moms who pioneered “nanny cams” to spy on their expensive childcare providers. It was the model for the absurd lifestyle that her alter ego, Carrie Bradshaw, would make famous, balancing small paychecks with major access to glamour and wealth. That inside perspective on the high life would become a key part of the column’s appeal.

• • •

Candace Bushnell knew nothing of private jets and nannies when she first arrived in Manhattan.

In fact, she lived in almost twelve different apartments during her first year in New York City, or at least it felt that way. Candy, as her family called her—honey-blond and Marcia Brady–pretty—had come to Manhattan to make it as an actress after she dropped out of Rice University. Then she found out she was a terrible actress, so she decided to make it as a writer instead.

Thus far, however, she’d only made it as a roommate, and even that wasn’t going well.

In one apartment, on East 49th Street, which was something of a red-light district at the time, she lived with three other girls. All three wanted to be on Broadway, and, even worse, one of them was. All they did was sing when they were home; when they weren’t home, they waitressed. Worse still, the women who lived above them on the third and fourth floors were hookers with a steady string of patrons clomping through.

Bushnell did her best to ignore the chaos and focus on her career. At a club one evening, she met the owner of a small publication called Night, where she landed her first entry-level gig. The magazine had just launched in 1978 to chronicle legendary nightclubs like Studio 54 and Danceteria. Other assistant-type work followed for Bushnell at Ladies’ Home Journal (where the mix of stories in a given month might include career advice from Barbara Walters, an exposé on sexually abusive doctors, and “low-cal party” ideas) and Good Housekeeping (which favored more traditional topics such as a “Calorie Watchers Cookbook,” White House table settings, and “How Charlie’s Angels Stay So Slim”). Finally, Bushnell landed on staff as a writer at Self in an era when cover stories included “Are You Lying to Yourself about Sex?” and “12 Savvy Ways to Make More Money.” This was at least a little closer to her speed.

Throughout the ’80s, when Bushnell was in her twenties, she found ways to write about the subjects that interested her most: sex, relationships, society, clubbing, singlehood, careers, and New York City. At that point she still thought she’d like to get married and have kids. But her work reflected the times and spoke to the millions of young women who poured into big cities to seek career success and independence instead of matrimony and family life. To pursue her own big-city dreams, Bushnell braved New York at its lowest point, when the AIDS crisis ravaged lives, graffiti covered buildings and subway cars inside and out, beefy vigilantes called the Guardian Angels roamed the streets to discourage criminals, and Times Square was populated with prostitutes and peep shows.

• • •

It was the Observer column that would ultimately catapult her to the next level of her career. Bushnell and Kaplan got down to practicalities. She’d be paid $1,000 per column, which was $250 more than other columnists at the paper were paid. This, plus her Vogue checks and perks like flights to Los Angeles for assignments, added up to a decent New York lifestyle for the time, particularly given her frugal living quarters. Bushnell and Kaplan discussed the title of her new column and settled on “Sex and the City.” A perfect newspaper column title: “pithy,” as she’d later describe it. The column was headed by an illustration of a shoe, based on a strappy pair of Calvin Klein sandals Bushnell had purchased for herself on sale.

As Bushnell later wrote, she “practically skipped up Park Avenue with joy” leaving the office after Kaplan offered her the column.

But first things first: What to write about for her “Sex and the City” debut? Well, there was that sex club everyone was talking about.

• • •

One late night in 1994, Bushnell left a dinner party at the new Bowery Bar to head uptown to a sex club on 27th Street. She didn’t know what would happen, but hoped it would be enough to fill her new column. As it turned out, Le Trapeze was, like most sexual escapades, neither as good nor as bad as imagined. It cost eighty-five dollars to enter, cash, no receipt. (Her expense reports were about to get interesting.) The presence of a hot-and-cold buffet took her aback. “You must have your lower torso covered to eat,” said a sign above. Bushnell spied “a few blobby couples” having sex on a large air mattress in the center of the room. And, as Bushnell wrote, “many men . . . appeared to be having trouble keeping up their end of the bargain.” A woman sat next to a Jacuzzi in a robe, smoking.

This experience became Bushnell’s first “Sex and the City” column, published on November 28, 1994, with the headline “Swingin’ Sex? I Don’t Think So.” Despite the come-on of the column’s name, it contained a traditional and wholesome bottom line: “I had learned that when it comes to sex, there’s no place like home.” Over the next two years, Bushnell would chronicle the gulf between fantasy and reality, between what the hippest of the hip of New York City thought they should be doing and what they truly wanted in their souls. If they could find their souls.

As Bushnell wrote in that first piece: “Sex in New York is about as much like sex in America as other things in New York are. It can be annoying; it can be unsatisfying; most important, sex in New York is only rarely about sex. Most of the time it’s about spectacle, Todd Oldham dresses, Knicks tickets, the Knick [sic] themselves, or the pure terror of Not Being Alone in New York.”

Over the next two years, Bushnell would sit at her desk in her friend’s apartment on the tenth floor of the 79th Street building, writing her column. She smoked and looked out on an air shaft from the dark three-bedroom apartment as she pondered the lives and loves of those she knew and tapped away on her Dell laptop keyboard. The words she wrote would turn her from a midlevel writer into a New York celebrity.

Her column gained such notoriety, in fact, that it affected her love life. High-powered men she met told her, “I thought about dating you, but now I won’t because I don’t want to end up in your column.” She would think, You aren’t interesting enough to write about anyway. Her on-again, off-again boyfriend, Vogue publisher Ron Galotti—a tanned man with slicked-back hair and a penchant for gray suits with pocket squares—did make the column regularly, referred to as “Mr. Big.” When she’d finish writing a column and show it to him, he would read her copy and issue his version of a compliment: “Cute, baby, cute.”

• • •

Bushnell never envisioned a mass audience for her work in the Observer. She never would have believed, at the time, that it would turn into a TV hit that all of America—much less the world—embraced. She only hoped to hook the select, in-the-know audience the Observer was known for, the upper echelons of high society. Bushnell’s “Sex and the City” column emphasizes opportunistic women on the hunt for financial salvation in Manhattan’s high-rolling men; her “Carrie Bradshaw”—a pseudonym for Bushnell herself—is unhinged and depressed; her friends have given up on the idea of love and connection. The result resembles a female version of Bright Lights, Big City and, in fact, the author of that book was her friend and frequent party mate Jay McInerney, whose wavy crest of dark hair, thick eyebrows, and natty style made him look more like a matinee idol than a novelist. Even McInerney, the chronicler of New York’s party culture of the coke-fueled ’80s, cracked that Bushnell “was doing advanced postgraduate work in the subject of going out on the town.”

She went out nearly every night, interviewed people at her central downtown hangout, Bowery Bar, and found stories all across town. New York was, Bushnell says, a “tight place then. It was the day when restaurants were theater. Nobody cared about the food. You just saw who was coming in, who talked to who.” If you wanted to know what was going on somewhere, you had to go there.

New York dating rituals still hearkened back to another era, “like in Edith Wharton’s time,” Bushnell says. “There were hierarchies. Society was important, the idea of wanting to be in society.” Women still often felt as if they had to please men, like Wharton wrote in The House of Mirth of her character Lily Bart: “She had been bored all the afternoon by Percy Gryce—the mere thought seemed to waken an echo of his droning voice—but she could not ignore him on the morrow, she must follow up her success, must submit to more boredom, must be ready with fresh compliances and adaptabilities.”

With the column, Bushnell had made herself into a professional dater. She got her material from dating, and she could use her profession to meet potential dates. This linked her to the city’s earliest recognized wave of professional, single women: the shopgirls of the early 1900s. They made their living as retail clerks, but more important they were single girls whose jobs gave them access to wealthy men: “Shopgirls knew that dressing and speaking the right ways would help them get a job, and that the right job could help them get a man,” Moira Weigel wrote in her history of courtship, Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating.

Bushnell and her friends had become the modern version of Edith Wharton heroines and those shopgirls, stuck between dependence on men and modern dating practices that lacked manners and rules. She envisioned herself writing for this select subculture, whispering their secrets to others like them, and perhaps even to the men who pursued them.

“SEX” BEYOND THE UPPER EAST SIDE

Before long, people began to buy the Observer just to read Bushnell’s column, people outside the Observer’s standard readership. Readers loved to guess the real identities of Bushnell’s pseudonymed characters. It was said that the writer “River Wilde” was probably Bret Easton Ellis, the American Psycho author. “Gregory Roque” was most likely Oliver Stone, the Natural Born Killers filmmaker. A Bushnell pseudonym became a status symbol of the time.

Soon everyone in town knew that Mr. Big was Galotti, the magazine publisher who drove a Ferrari and had dated supermodel Janice Dickinson. In the column, Bushnell, as a first-person narrator, introduces Mr. Big’s paramour, Carrie Bradshaw, as her “friend.” Eventually, detailed depictions of Carrie’s life—her thoughts, her word-for-word conversations, her sexual escapades—overtake the column. That, plus their shared initials, made it hard to imagine Carrie wasn’t Candace. In fact, Bushnell later revealed she’d created Carrie so her parents wouldn’t know—at least for sure—that they were reading about their daughter’s own sex life.

Readers took in every word. They read it on the subway and on the way out to the Hamptons. They delighted in Bushnell’s dissections of city types such as “psycho moms,” “bicycle boys,” “international crazy girls,” “modelizers,” and “toxic bachelors,” and they devoured the knowing insider commentary:

“It all started the way it always does: innocently enough.”

“On a recent afternoon, seven women gathered in Manhattan over wine, cheese, and cigarettes, to animatedly discuss the one thing they had in common: a man.”

“The pilgrimage to the newly suburbanized friend is one that most Manhattan women have made, and few truly enjoyed.”

“On a recent afternoon, four women met at an Upper East Side restaurant to discuss what it’s like to be an extremely beautiful young woman in New York City.”

“There are worse things than being thirty-five, single, and female in New York. Like: Being twenty-five, single, and female in New York.”

Bushnell’s column contained seedlings of the fantasy life that would bloom in Sex and the City the television show. But “Sex and the City,” as a column, was a bait and switch. The clothes command high prices and the parties attract big names; however, despite the column’s name, there isn’t much sexy sex and there’s almost no romance. One character sums it up: “I have no sex and no romance. Who needs it? No fear of disease, psychopaths, or stalkers. Why not just be with your friends?” Bushnell puts it this way: “Relationships in New York are about detachment.” The writer herself had soured on marriage, telling the New York Times it was an institution that favored men. She’d once been engaged, about four years before the launch of her column, and the experience had made her feel as if she were, she said, “drowning.”

Despite the column’s cynical soul, despite Bushnell’s personal connection with novelist friends Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis, she knew how her writing—because it was about women and feelings—was perceived.

“It’s cute. It’s light. . . . It’s not Tolstoy,” is how her friend Samantha describes Carrie’s work in one of the columns. Carrie insists that she’s not trying to be Tolstoy. Bushnell concludes, “But, of course, she was.”

WRITING AND THE SINGLE GIRL

Bushnell’s column fit into a long tradition of literary fascination with single women’s lives. The title of the column, in fact, referenced the most famous of them all: Helen Gurley Brown’s 1962 sensation Sex and the Single Girl. While women have never been published with the same frequency as their white male counterparts, they have proven throughout history that there was a surefire way to get attention: by explaining their exotic lives as single, independent creatures to the masses. How on earth did they survive without men? Was it as awful as it sounded? Was it as fun?

This phenomenon dated back at least as far as 1898, when Neith Boyce wrote a column for Vogue called “The Bachelor Girl.” “The day it became evident that I was irretrievably committed to this alternative lifestyle was a solemn one in the family circle,” Boyce wrote. “I was about to leave that domestic haven, heaven only knew for what port. I was going to New York to earn my own bread and butter and to live alone.”

With “Sex and the City,” Bushnell combined two historically popular column genres: the confessions of a single professional woman and the documentation of high society’s charity events, fashion, fancy homes, and gossip. She offered a juicier version of the age-old society pages.

Given this winning combination, the book publishing world inevitably pursued Bushnell. Atlantic Monthly Press released a collection of Bushnell’s columns in hardcover in August 1996. As she toured college campuses to promote the book, she noticed something unexpected: The column resonated far beyond Manhattan, far beyond its outer boroughs . . . and far beyond even the Tri-State Area. Women in Chicago, Los Angeles, and other cities throughout the nation saw their own lives in Sex and the City. They had their own Mr. Bigs; they were their own Carrie Bradshaws. “We thought people could only be this terrible in New York,” Bushnell says. “But this phenomenon of thirty-something women dating was much more universal than we thought.” She wasn’t just reporting on high society for in-the-know Manhattanites; she had become the new Holly Golightly, the glamorous single woman her college fans hoped to be someday.

The book represented an unquestionable pinnacle for Bushnell’s career. She had chased exactly this kind of fantasy from the Connecticut suburbs to New York City in 1978 with no connections, no Ivy League degree, and no money, then worked her way up the media ladder.

Reviews for the book, however, ran lukewarm. The Washington Post called it “mildly amusing,” then used most of the review to take aim at the Observer, “a singularly peculiar weekly newspaper that is printed on colored paper and edited with only two circulation areas in mind: chic Manhattan and drop-dead Hamptons.” The book, the review said, did nothing more than collate several of Bushnell’s columns, “presumably for the convenience of those who do not have their copies of the Observer bound by Madison Avenue leather crafters.”

Some reviewers mustered up more respect, like Sandra Tsing Loh in the Los Angeles Times, who compared Bushnell’s view of New York City to those of some of Bushnell’s friends, influential members of the ’80s “literary Brat Pack” such as Jay McInerney and Tama Janowitz. A Publishers Weekly review noted the “opulent debasement that suffuses this collection” and called it “brain candy”—emphasis on the “brain” as much as the “candy.”

The “candy,” however, took over as the main public perception of Sex and the City as a book. Sex and the City’s publication coincided with the introduction of another memorable thirtysomething singleton into the literary landscape: British columnist Helen Fielding’s hapless Bridget Jones. Comparisons flourished, and did nothing to boost Sex and the City’s respectability. Alex Kuczynski in the New York Times described Bridget’s obsession with men as “perfectly normal behavior, if you’re a 13-year-old girl,” then acknowledged that Bridget “makes some women laugh in sad recognition.”

In the Village Voice Meghan Daum wrote that Bridget Jones “concerns itself almost entirely with the neurotic fallout of popular women’s culture. . . . Bridget’s constant failure to follow through on even the most basic lifestyle tips offered up by her mentor, Cosmo culture, will undoubtedly provoke the disapproval of those who remain devoted to that culture’s major tenet, that self-improvement and positive thinking are synonymous with substance.”

With the exception of that last one, these reviews seemed oblivious to Bridget’s satirical nature, the fact that she and her creator were in on the joke. But Bridget and Carrie did not belong together in any sense, even though they kept getting stuck together in trend pieces. Kuczynski’s New York Times piece quotes Bushnell criticizing Bridget as “ten years out of date.” Bridget struggled with her weight and suffered from low self-esteem, but also seemed to like her life, her friends, her family, and her middle-class status. Carrie, on the other hand, knew how attractive and thin she was, dated and drank with the upper echelons of Manhattan society, and was still moody and cynical. Where Bridget was sweet and well-adjusted underneath her snark and borderline alcoholism, Carrie suffered mood swings and self-sabotaging behavior. In short, they sat at opposite ends of the single-woman character spectrum: Bridget an updated version of the single woman who knows her place, and thus is quite likable; Carrie an unsympathetic character, a true antiheroine at a time when unlikable lead female characters were rare. “I don’t write books because I want everyone to like the characters,” Bushnell says. “These are women who make some choices that maybe aren’t the best choices in terms of morality.”

With Carrie, Bushnell was going more for a Dorothy Parker type or Edith Wharton heroine than the lead of a romantic comedy, but she and Fielding were linked in the cultural ether and credited with—or blamed for—the advent of a new, much-derided book category equivalent of the rom-com: chick lit.

• • •

Whatever the perception of “Sex and the City,” it was popular. So popular, in fact, that starting about three months into the column’s run, enamored New Yorkers in the media business began faxing copies of it to their friends in the movie business in Los Angeles. Even before the collection of columns came out in book form, Bushnell began to get calls from producers eager to buy the rights for film.

TV network ABC also pursued her, particularly executive Jamie Tarses after she became president of ABC Entertainment in 1996. During her previous job at NBC, Tarses had developed Caroline in the City, Mad About You, and Friends—all New York–centric hits about young, beautiful white people. It made sense that she’d be interested in Sex and the City, which she saw as a more sophisticated, forward-thinking version of those shows. The thirty-two-year-old had just become the youngest person to run a network entertainment division at the time; she was also the first female network president ever. Industry observers were waiting for her to fail. Her new network lagged in third place of the Big Three. She needed a standout hit, and she thought a “Sex and the City” adaptation could be it.

Tarses’s thick, curly, Sarah Jessica Parker–like hair, blue eyes, and power suits would have made her look right at home on Sex and the City. Like many of the female characters, she was in her early thirties and trying to balance dating with a high-powered career. She had become a fan of Bushnell’s column and its perspective on modern relationships because she related to it. The column felt like it could become the basis of the show she had always been looking for, a voice and point of view that wasn’t already represented on television. The popularity of the column and subsequent book gave the title a recognizability that made it perfect for TV. And it appealed to the female audience ABC most wanted at the time. Tarses just had to figure out how much of the “sex” a broadcast network could allow.

As Bushnell’s star rose, the writer ran into Tarses and her boyfriend, David Letterman’s executive producer Robert Morton, in the Hamptons. Bushnell was Rollerblading when the couple pulled up next to her, as she remembers it, in a cherry-red Mercedes convertible. “Jamie wants to buy ‘Sex and the City,’?” Morton told Bushnell. “ABC’s really interested.” The pursuit was on.

But others were wooing Bushnell for the “Sex and the City” rights as well. One of Galotti’s friends, Richard Plepler—senior vice president of communications at HBO—also thought the column would be a perfect fit for his pay-cable network. Bushnell and Plepler often saw each other at the stretch of shoreline called Media Beach in the Hamptons, and every time, he’d urge her to come to a meeting at HBO.

• • •

Cable seemed like a better fit for Sex and the City, given its similarities to another book that started as a newspaper column, then became a critically acclaimed series for PBS and, later, cable network Showtime: Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. In fact, that Publishers Weekly review that called Sex and the City “brain candy” also referred to Maupin’s 1978 collection of San Francisco Chronicle columns that followed young, single people of various sexual orientations in the liberated city: “The effect is that of an Armistead Maupin–like canvas tinged with a liberal smattering of Judith Krantz,” the reviewer wrote.

Tales of the City had become a television miniseries around the same time “Sex and the City” debuted as a column; it premiered in the UK in 1993 and in the United States on PBS in 1994. The series took on issues well ahead of its time for TV, with extramarital affairs, sex, several gay love affairs, and a major transgender character. But like Sex and the City after it, Tales’ true message came down to the importance of friendship in a major metropolitan area. It also highlighted a different kind of love affair that Sex and the City would also emphasize: the relationship between a city and its denizens.

Tales couldn’t afford to be a glitzy production, however, when it came to television. Such a risky proposition meant a miniscule budget, with costumes even for its wealthiest characters coming from secondhand shops. “It was a total shoestring,” says Barbara Garrick, who played heiress DeDe Halcyon Day (and would later guest-star on Sex and the City as a spagoer who gets a happy ending from her massage therapist). “They’d hand you a dress they just bought at Goodwill.”

Tales’ frank approach to modern sexuality won it plenty of attention, both good and bad. It became the highest-rated broadcast to date on PBS at the time, but also sparked controversy as one of the few US programs to show kissing between male lovers. Attempts to produce a follow-up based on Maupin’s book series had so far failed because of the US government’s threats to pull PBS funding if it remained involved with Tales. “I did have my top off once [during the miniseries], and that went to Congress, like a pirate tape with black bars across my chest,” Garrick says. “It had all the scenes of the pot smoking and the guys kissing and the nudity.” Later, HBO rival Showtime would pick the show up for a second season.

This was the landscape into which any Sex and the City television show would take its first steps.

WHEN CANDACE MET DARREN

Just before the birth of the “Sex and the City” column, Bushnell had gone on an assignment that would change her life—and, even more, the life of her column. In fact, without this one routine assignment, the Sex and the City we know would never have come to pass.

Vogue had asked Bushnell to write a profile of Darren Star, a TV producer who had worked with Aaron Spelling to create Beverly Hills, 90210 and Melrose Place. Star had a new show on CBS, Central Park West, that transplanted his flashy, soapy approach to New York City, with Mariel Hemingway as a glamorous magazine editor and Lauren Hutton as her boss’s suspicious wife. Star was branching out on his own without Spelling, and the critics would be watching to see if Star was the real deal.

In the September 1995 piece, Bushnell follows Star—dressed “California-style” in a black Armani jacket and jeans—on a late-night visit to an S&M club called Vault, which he’s scouting for Central Park West. Star couldn’t have known at the time that it was the effect of this profile, not the show he was producing, that would resonate decades later.

Soon after the two met for the piece, Star moved to Manhattan, and Bushnell swept him into her orbit to show him around the area—for Central Park West research, of course. He had never met anyone more fun. She personified all the clichés: “A force of nature,” he says. “She opened a lot of doors.” She took him to clubs, and of course to Bowery Bar. They commemorated their friendship in ultimate Hollywood fashion: Bushnell would take the first half of her column pseudonym from Star’s nightlife columnist character on Central Park West, Carrie Fairchild, played by Mädchen Amick.

Star—a handsome gay man with brown, spiky hair—connected with Bushnell as a fellow suburban kid made good. He spent his childhood in Potomac, Maryland, a middle- to upper-class DC suburb full of politicians, ambassadors, and their families. Young Darren took film classes in high school and hoped to work in the movie industry as a writer and director. He used his bar mitzvah money to get himself a subscription to the show business trade publication Variety. While other kids partied or played sports, he made his own movies with his Super 8 camera. After graduating high school, he moved to California to study writing and film at UCLA, from which he graduated in 1983. Degree in hand, he took the classic first step toward a Hollywood career: He became a waiter.

He soon, however, got his first industry job. Star was working as a publicist for Showtime when he sold his first screenplay to Warner Bros. at age twenty-four. Doin’ Time on Planet Earth, a comedy about a teenager in Arizona who comes to believe he’s an alien prince, premiered in 1988, directed by Charles Matthau. It made little critical or commercial impact, but it helped launch Star’s career. He could now quit his job to write screenplays full-time. His next project would be If Looks Could Kill, with 21 Jump Street’s Richard Grieco as a high school French student who’s pulled into an international spy ring on a class trip.

As Star awaited that film’s release, he fulfilled a lifelong dream by moving from Los Angeles to New York City, a place whose glamour he had long admired from afar. But soon after, he got a call from Paul Stupin, a movie executive who’d just taken a job as head of drama at the new Fox television network. Stupin asked if Star would write a high school show, given his teen-oriented script experience. Stupin hoped to pair him with the much older producer Aaron Spelling (a golden TV touch who’d created 1970s hits The Love Boat and Charlie’s Angels) to create a high school series. Star thought he’d be crazy to turn down the chance to work with such a legend, which seemed like the perfect way to kill time while he waited for If Looks Could Kill to come out. So at age twenty-eight, he moved right back to Los Angeles to make a show with Spelling.