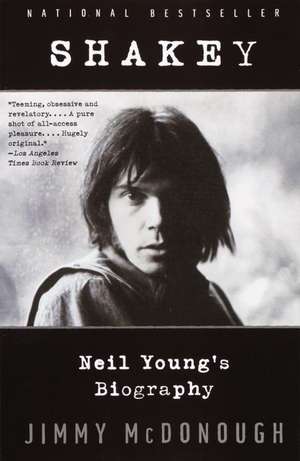

Shakey: Neil Young's Biography

Autor Jimmy McDonoughen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2003

Preț: 166.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 250

Preț estimativ în valută:

31.91€ • 33.19$ • 26.34£

31.91€ • 33.19$ • 26.34£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 74.18 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679750963

ISBN-10: 0679750967

Pagini: 816

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 28 mm

Greutate: 1 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0679750967

Pagini: 816

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 28 mm

Greutate: 1 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Jimmy McDonough is a journalist who has contributed to such publications as Variety, Film Comment, Mojo, Spin, and Juggs. But he is perhaps best known for his intense, definitive Village Voice profiles of such artists as Jimmy Scott, Neil Young, and Hubert Selby, Jr. Jimmy is also the author of The Ghastly One: The Sex-Gore Netherworld of Filmmaker Andy Milligan. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Extras

Innaresting characters

–Who gave you the Nixon mask?

I can’t recall, as John Dean would say. I’ll always tell ya if I remember, Jimmy. You talk about things and it comes back.

–Every question seems to stir up something in you.

Not the answers you were looking for . . . but they’re answers, heh heh. Hard to remember things. It’s all there, though. Maybe we oughta go into hypnotherapy, fuckin’ go right back. Take like, six months to get zoned in on the Tonight’s the Night sessions–exactly what was happening? “Okay, we’re gonna go back a little further today, Neil. . . .”

–I’m frustrated.

Hey, well, you’ve been frustrated since the beginning, heh heh. You’re not frustrated because of this–we’re doing it. You’re asking questions and I’m answering them. What could be less frustrating than THAT?

–Maybe I should tell people in the intro you don’t wanna do the book.

You can tell ’em if you want. The bottom line is if it went against the grain so hard, I wouldn’t be doin’ it. The thing is, it’s not necessarily my first love. I think that’s a subtle way of puttin’ it. Heh heh.

The first time Jon McKeig really encountered Shakey he was under a car. Shakey’s a nickname–from alter ego Bernard Shakey, sometime moviemaker. It’s just one of many aliases: Joe Yankee, overdubber; Shakey Deal, blues singer; Phil Perspective, producer.

The world knows him as Neil Young.

McKeig had been toiling away on Nanoo, a blue and white ’59 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz convertible of Young’s, for months without actually seeing him. The car was a mess, but McKeig would soon realize that this was Shakey’s M.O., buying beyond-dead wrecks for peanuts, then sparing no expense to bring them back to life. “I can name five automobiles he has that the parts cars were in better shape than the cars that were restored.” McKeig shook his head. “That’s extreme. I don’t believe anybody anywhere goes to that length. If the car smells wrong, you’re screwed; if it squeaks, it’s not cool . . . he’s fanatical.”

One day Neil happened in for a personal inspection. “Neil came right over to the car, looked at it and–I’ll be damned–all of a sudden he went down to the concrete and slid right underneath. All you could see was his tennis shoes.”

McKeig asked Young how far he wanted to go with the thrashed Cadillac. “Neil looked me straight in the eye and said calmly, ‘As long as it’s museum quality.’ ” McKeig shuddered. “I never heard it said like that–‘museum quality.’ Then he left. That’s all that was said. I never saw him–for years after.” Decades later, Nanoo still isn’t finished.

Cars are a major part of Shakey’s world. He’s written countless songs in them and they figure into more than a few of his lyrics: “Trans Am,” “Long May You Run,” “Motor City,” “Like an Inca (Hitchhiker),” “Drifter,” “Roll Another Number (For the Road),” “Sedan Delivery,” “Get Gone”; the list goes on.

Young would even advise me on touch-up paint and carburetor problems–until I flipped my ’66 Falcon Futura twice off the side of a two-lane, nearly killing myself. Out on the road in his bus, Young called me a few days after. “See, Neil?” I said. “You tried to bump me off, but I’m still here. Now I gotta finish the book.’’ Unnerved, he immediately called back after we hung up. “Jimmy,” he said, his voice awash in cellular static, “just want ya to know I’m glad ya didn’t die in the wreck.” Shakey and I had a colorful relationship. But that was all in the future.

Right now it was April 1991, and I was in Los Angeles, watching McKeig–now Young’s live-in auto restorer and maintenance man–pilot members of Neil’s family through the service areas of the L.A. Sports Arena in a sleek black ’54 Caddy that Young called Pearl: He nicknames everything. It was a stunning vehicle. He had paid $400 for the car in 1974 and spent years and a fortune restoring it. Legend has it that some rich Arab saw Young tooling Pearl through Hollywood and offered him a pile of loot on the spot.

Out of the Caddy’s backseat emerged Neil’s wife, Pegi, a striking blonde and a powerful force in her own right. She and Neil have two children, Ben and Amber. Family is a priority to both of them. Ben, born spastic, nonoral and quadriplegic, went everywhere with his mom and pop. It wasn’t unusual to see him at the side of the stage in his wheelchair, watching his father work.

“Spud,” Ben’s nickname, graced the door of Pocahontas, which was parked not far from Pearl. A huge, Belgian-made ’70 Silver Eagle, forty feet long and sporting a souped-up mill, the bus had been Young’s home on the road since 1976. Young had gone to outlandish lengths in customizing it. Down one side was an extravagant stained-glass comet circling the earth; the roof was domed with vintage Hudson Hornet/Studebaker Starlight Coupe cartops that acted as skylights. The interior of the bus–designed under Young’s supervision to resemble the skeletal structure of a giant bird–was lavish with hand-carved wood, down to the door handle of the microwave. Above the big front windows hung a large brass eagle’s eye. “This bus is so fucked up and over the top,” Young would tell me with a grin. “Which is just how I was back in the mid-seventies when I built it.”

Bus driver Joe McKenna was making sure Pocahontas was shipshape for Neil’s arrival. An Irishman with a low-slung belly, a silver pompadour and a voice lower than a frog’s, Joe loved the golf course and let little faze him. He seemed to have a calming effect on Young, who once dubbed him “The Lucky Leprechaun.” McKenna would beat cancer after Young helped him get alternative medical help. “Neil Young saved my life,” he told me. “Put that in your book.”

Next to the steering wheel hung a sign that read in bold block letters, don’t spill the soup.

I wouldn’t have driven that bus for love, money or drugs. When it came to Pocahontas, Shakey was like a hawk. He knew every ding and dimple and wanted the ones he didn’t know explained immediately.

An intense relationship with his bus drivers, I mused, but tour manager Bob Sterne set me straight. “In all honesty, I think the intense relationship is with the bus,” said Sterne, a big, bearded, no-nonsense monolith with a constantly peeling nose and sporting a Cruex jock itch ointment T-shirt. Sterne and Joe McKenna weren’t exactly the best of pals.

Sterne was forever seeking info on Young’s elusive doings and one of McKenna’s jobs was to keep the world away.

Bob was no stranger to that task–his makeshift office inside the sports arena was plastered with signs like if you want a backstage pass, get lost. Sterne was hard-core. It came with the territory. “Neil’s not gonna do what you think he’s gonna do or what he said last week–it’s not a good place for the average person to be. The people who are looking for a paycheck don’t last long.”

Young likes to keep everyone on their toes. “Neil’s come to me and said, ‘Go get all the set lists and throw ’em in the trash can’–and he said this to me fifteen minutes before the show,” said Sterne. “He’s not just talking about the band’s set list, he’s talking about the lighting guys, the sound guys–every single set list in the building.”

Sitting in the office not far from Sterne was Tim Foster, Young’s stage manager and primary roadie. Foster had worked for Young off and on–mostly on–since 1973. With a Dick Tracy chin, a mustache and a baseball cap pulled down to his eyes, Foster saw everything and said little. “Tim never gets flustered,” said Sterne. “He understands Neil has no schedule.”

Making his way through the backstage maze out to the arena’s mixing station was Tim Mulligan, his long hair, mustache and shades making him look like the world’s most sullen Doobie Brother. Nothing impresses Mulligan. He’s been working on Young’s albums and mixing his live sound for decades. “Producers, engineers come and go,” said Sterne. “Mulligan hangs in there. He doesn’t have an opinion.” Tim lives alone on Young’s ranch, without a phone. “Mulligan has this incredible allegiance,” said longtime Young associate “Ranger Dave” Cline. “He lives and breathes Neil. It’s his whole life.”

It took years for Mulligan to warm to me, and even then he wouldn’t give me an interview, just tersely answered a few questions. Getting any one of Young’s crew to talk was like breaking into the Mafia. They were fiercely devoted, and although they’d all been subject to the ferocious twists and turns of Neil’s psyche, most had been around for decades. And every one of them was an individual. “Innaresting characters,” as Young would put it. “They’re all Neil,” said Graham Nash. “They all represent a slice of Neil’s personality.”

“Neil likes quirky people around him,” said Elliot Roberts, Young’s manager since the late sixties. “I think having quirky people around him lessens–in his mind–his own quirkiness. ‘Yes, I am standing on my head, but look at these two other guys nude standing on their head.’ ”

His mane of gray hair flying, Roberts was on his ninety-sixth phone call of the day, either chewing out some record-company underling or closing a million-dollar deal. Not far away, a bearded, sunglassed David Briggs–Young’s producer–prowled the stage, palming a cigarette J.D.-style and looking like the devil himself. Briggs and Roberts were the twin engines that powered the Neil Young hot rod. Feared, at times hated, both men possessed killer instincts and had been with Neil almost from the beginning. Roberts was a genius at pushing Young’s career, Briggs at pushing his art. It’s an understatement to say the two didn’t always see eye to eye.

Roberts and Briggs were two of the quirkiest characters around–difficult, complicated men–but then so was just about everybody and everything in Young’s world. “Let’s look at Neil’s whole trip–the ranch, the people he plays with,” said computer wizard Bryan Bell, who worked extensively with Young in the late eighties. “ ‘Easy’ isn’t in the vocabulary.”

“Neil is wonderful to work for in many ways and very difficult to work with in many ways,” said Roger Katz, former captain of Young’s boat. “He’s able to control most everything.” As David Briggs put it, “It’s not fun at all working with Neil–fun’s not part of the deal–but it’s very fulfilling.”

I asked Young’s guitar tech Larry Cragg what the hardest tour had been. “All of ’em,” he said. “They’ve all been rough–every one of ’em made workin’ for anybody else real easy. The tours are out of the ordinary, the music, the movies–everything’s out of the ordinary. We do things differently around here. That’s just the way it is.”

Cragg was tinkering with Young’s guitar rig, which sat in a little area to the rear of the stage. A gaggle of amps–a Magnatone, a huge transistorized Baldwin Exterminator, a Fender Reverb unit and the heart of it all: a small, weather-beaten box covered in worn-out tweed, 1959 vintage. “The Deluxe,” muttered amp tech Sal Trentino with awe.

“Neil’s got four hundred and fifty-six identical Deluxes. They sound nothing like this one.” Young runs the amp with oversized tubes, and Cragg has to keep portable fans trained on the back so it doesn’t melt down. “It really is ready to just go up in smoke, and it sounds that way–flat-out, overdriven, ready to self-destruct.”

Young has a personal relationship with electricity. In Europe, where the electrical current is sixty cycles, not fifty, he can pinpoint the fluctuation–by degrees. It dumbfounded Cragg. “He’ll say, ‘Larry, there’s a hundred and seventeen volts coming out of the wall, isn’t there?’ I’ll go measure it, and yeah, sure–he can hear the difference.”

Shakey’s innovations are everywhere. Intent on controlling amp volume from his guitar instead of the amp, Young had a remote device designed called the Whizzer. Guitarists marvel at the stomp box that lies onstage at Young’s feet: a byzantine gang of effects that can be utilized without any degradation to the original signal. Just constructing the box’s angular red wooden housing to Young’s extreme specifications had craftsmen pulling their hair out.

Cradled in a stand in front of the amps is the fuse for the dynamite, Young’s trademark ax–Old Black, a ’53 Gold Top Les Paul some knothead daubed with black paint eons ago. Old Black’s features include a Bigsby wang bar, which pulls strings and bends notes, and a Firebird pickup so sensitive you can talk through it. It’s a demonic instrument. “Old Black doesn’t sound like any other guitar,” said Cragg, shaking his head.

For Cragg, Old Black is a nightmare. Young won’t permit the ancient frets to be changed, likes his strings old and used, and the Bigsby causes the guitar to go out of tune constantly. “At sound check, everything will work great. Neil picks up the guitar, and for some reason that’s when things go wrong.”

–Who gave you the Nixon mask?

I can’t recall, as John Dean would say. I’ll always tell ya if I remember, Jimmy. You talk about things and it comes back.

–Every question seems to stir up something in you.

Not the answers you were looking for . . . but they’re answers, heh heh. Hard to remember things. It’s all there, though. Maybe we oughta go into hypnotherapy, fuckin’ go right back. Take like, six months to get zoned in on the Tonight’s the Night sessions–exactly what was happening? “Okay, we’re gonna go back a little further today, Neil. . . .”

–I’m frustrated.

Hey, well, you’ve been frustrated since the beginning, heh heh. You’re not frustrated because of this–we’re doing it. You’re asking questions and I’m answering them. What could be less frustrating than THAT?

–Maybe I should tell people in the intro you don’t wanna do the book.

You can tell ’em if you want. The bottom line is if it went against the grain so hard, I wouldn’t be doin’ it. The thing is, it’s not necessarily my first love. I think that’s a subtle way of puttin’ it. Heh heh.

The first time Jon McKeig really encountered Shakey he was under a car. Shakey’s a nickname–from alter ego Bernard Shakey, sometime moviemaker. It’s just one of many aliases: Joe Yankee, overdubber; Shakey Deal, blues singer; Phil Perspective, producer.

The world knows him as Neil Young.

McKeig had been toiling away on Nanoo, a blue and white ’59 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz convertible of Young’s, for months without actually seeing him. The car was a mess, but McKeig would soon realize that this was Shakey’s M.O., buying beyond-dead wrecks for peanuts, then sparing no expense to bring them back to life. “I can name five automobiles he has that the parts cars were in better shape than the cars that were restored.” McKeig shook his head. “That’s extreme. I don’t believe anybody anywhere goes to that length. If the car smells wrong, you’re screwed; if it squeaks, it’s not cool . . . he’s fanatical.”

One day Neil happened in for a personal inspection. “Neil came right over to the car, looked at it and–I’ll be damned–all of a sudden he went down to the concrete and slid right underneath. All you could see was his tennis shoes.”

McKeig asked Young how far he wanted to go with the thrashed Cadillac. “Neil looked me straight in the eye and said calmly, ‘As long as it’s museum quality.’ ” McKeig shuddered. “I never heard it said like that–‘museum quality.’ Then he left. That’s all that was said. I never saw him–for years after.” Decades later, Nanoo still isn’t finished.

Cars are a major part of Shakey’s world. He’s written countless songs in them and they figure into more than a few of his lyrics: “Trans Am,” “Long May You Run,” “Motor City,” “Like an Inca (Hitchhiker),” “Drifter,” “Roll Another Number (For the Road),” “Sedan Delivery,” “Get Gone”; the list goes on.

Young would even advise me on touch-up paint and carburetor problems–until I flipped my ’66 Falcon Futura twice off the side of a two-lane, nearly killing myself. Out on the road in his bus, Young called me a few days after. “See, Neil?” I said. “You tried to bump me off, but I’m still here. Now I gotta finish the book.’’ Unnerved, he immediately called back after we hung up. “Jimmy,” he said, his voice awash in cellular static, “just want ya to know I’m glad ya didn’t die in the wreck.” Shakey and I had a colorful relationship. But that was all in the future.

Right now it was April 1991, and I was in Los Angeles, watching McKeig–now Young’s live-in auto restorer and maintenance man–pilot members of Neil’s family through the service areas of the L.A. Sports Arena in a sleek black ’54 Caddy that Young called Pearl: He nicknames everything. It was a stunning vehicle. He had paid $400 for the car in 1974 and spent years and a fortune restoring it. Legend has it that some rich Arab saw Young tooling Pearl through Hollywood and offered him a pile of loot on the spot.

Out of the Caddy’s backseat emerged Neil’s wife, Pegi, a striking blonde and a powerful force in her own right. She and Neil have two children, Ben and Amber. Family is a priority to both of them. Ben, born spastic, nonoral and quadriplegic, went everywhere with his mom and pop. It wasn’t unusual to see him at the side of the stage in his wheelchair, watching his father work.

“Spud,” Ben’s nickname, graced the door of Pocahontas, which was parked not far from Pearl. A huge, Belgian-made ’70 Silver Eagle, forty feet long and sporting a souped-up mill, the bus had been Young’s home on the road since 1976. Young had gone to outlandish lengths in customizing it. Down one side was an extravagant stained-glass comet circling the earth; the roof was domed with vintage Hudson Hornet/Studebaker Starlight Coupe cartops that acted as skylights. The interior of the bus–designed under Young’s supervision to resemble the skeletal structure of a giant bird–was lavish with hand-carved wood, down to the door handle of the microwave. Above the big front windows hung a large brass eagle’s eye. “This bus is so fucked up and over the top,” Young would tell me with a grin. “Which is just how I was back in the mid-seventies when I built it.”

Bus driver Joe McKenna was making sure Pocahontas was shipshape for Neil’s arrival. An Irishman with a low-slung belly, a silver pompadour and a voice lower than a frog’s, Joe loved the golf course and let little faze him. He seemed to have a calming effect on Young, who once dubbed him “The Lucky Leprechaun.” McKenna would beat cancer after Young helped him get alternative medical help. “Neil Young saved my life,” he told me. “Put that in your book.”

Next to the steering wheel hung a sign that read in bold block letters, don’t spill the soup.

I wouldn’t have driven that bus for love, money or drugs. When it came to Pocahontas, Shakey was like a hawk. He knew every ding and dimple and wanted the ones he didn’t know explained immediately.

An intense relationship with his bus drivers, I mused, but tour manager Bob Sterne set me straight. “In all honesty, I think the intense relationship is with the bus,” said Sterne, a big, bearded, no-nonsense monolith with a constantly peeling nose and sporting a Cruex jock itch ointment T-shirt. Sterne and Joe McKenna weren’t exactly the best of pals.

Sterne was forever seeking info on Young’s elusive doings and one of McKenna’s jobs was to keep the world away.

Bob was no stranger to that task–his makeshift office inside the sports arena was plastered with signs like if you want a backstage pass, get lost. Sterne was hard-core. It came with the territory. “Neil’s not gonna do what you think he’s gonna do or what he said last week–it’s not a good place for the average person to be. The people who are looking for a paycheck don’t last long.”

Young likes to keep everyone on their toes. “Neil’s come to me and said, ‘Go get all the set lists and throw ’em in the trash can’–and he said this to me fifteen minutes before the show,” said Sterne. “He’s not just talking about the band’s set list, he’s talking about the lighting guys, the sound guys–every single set list in the building.”

Sitting in the office not far from Sterne was Tim Foster, Young’s stage manager and primary roadie. Foster had worked for Young off and on–mostly on–since 1973. With a Dick Tracy chin, a mustache and a baseball cap pulled down to his eyes, Foster saw everything and said little. “Tim never gets flustered,” said Sterne. “He understands Neil has no schedule.”

Making his way through the backstage maze out to the arena’s mixing station was Tim Mulligan, his long hair, mustache and shades making him look like the world’s most sullen Doobie Brother. Nothing impresses Mulligan. He’s been working on Young’s albums and mixing his live sound for decades. “Producers, engineers come and go,” said Sterne. “Mulligan hangs in there. He doesn’t have an opinion.” Tim lives alone on Young’s ranch, without a phone. “Mulligan has this incredible allegiance,” said longtime Young associate “Ranger Dave” Cline. “He lives and breathes Neil. It’s his whole life.”

It took years for Mulligan to warm to me, and even then he wouldn’t give me an interview, just tersely answered a few questions. Getting any one of Young’s crew to talk was like breaking into the Mafia. They were fiercely devoted, and although they’d all been subject to the ferocious twists and turns of Neil’s psyche, most had been around for decades. And every one of them was an individual. “Innaresting characters,” as Young would put it. “They’re all Neil,” said Graham Nash. “They all represent a slice of Neil’s personality.”

“Neil likes quirky people around him,” said Elliot Roberts, Young’s manager since the late sixties. “I think having quirky people around him lessens–in his mind–his own quirkiness. ‘Yes, I am standing on my head, but look at these two other guys nude standing on their head.’ ”

His mane of gray hair flying, Roberts was on his ninety-sixth phone call of the day, either chewing out some record-company underling or closing a million-dollar deal. Not far away, a bearded, sunglassed David Briggs–Young’s producer–prowled the stage, palming a cigarette J.D.-style and looking like the devil himself. Briggs and Roberts were the twin engines that powered the Neil Young hot rod. Feared, at times hated, both men possessed killer instincts and had been with Neil almost from the beginning. Roberts was a genius at pushing Young’s career, Briggs at pushing his art. It’s an understatement to say the two didn’t always see eye to eye.

Roberts and Briggs were two of the quirkiest characters around–difficult, complicated men–but then so was just about everybody and everything in Young’s world. “Let’s look at Neil’s whole trip–the ranch, the people he plays with,” said computer wizard Bryan Bell, who worked extensively with Young in the late eighties. “ ‘Easy’ isn’t in the vocabulary.”

“Neil is wonderful to work for in many ways and very difficult to work with in many ways,” said Roger Katz, former captain of Young’s boat. “He’s able to control most everything.” As David Briggs put it, “It’s not fun at all working with Neil–fun’s not part of the deal–but it’s very fulfilling.”

I asked Young’s guitar tech Larry Cragg what the hardest tour had been. “All of ’em,” he said. “They’ve all been rough–every one of ’em made workin’ for anybody else real easy. The tours are out of the ordinary, the music, the movies–everything’s out of the ordinary. We do things differently around here. That’s just the way it is.”

Cragg was tinkering with Young’s guitar rig, which sat in a little area to the rear of the stage. A gaggle of amps–a Magnatone, a huge transistorized Baldwin Exterminator, a Fender Reverb unit and the heart of it all: a small, weather-beaten box covered in worn-out tweed, 1959 vintage. “The Deluxe,” muttered amp tech Sal Trentino with awe.

“Neil’s got four hundred and fifty-six identical Deluxes. They sound nothing like this one.” Young runs the amp with oversized tubes, and Cragg has to keep portable fans trained on the back so it doesn’t melt down. “It really is ready to just go up in smoke, and it sounds that way–flat-out, overdriven, ready to self-destruct.”

Young has a personal relationship with electricity. In Europe, where the electrical current is sixty cycles, not fifty, he can pinpoint the fluctuation–by degrees. It dumbfounded Cragg. “He’ll say, ‘Larry, there’s a hundred and seventeen volts coming out of the wall, isn’t there?’ I’ll go measure it, and yeah, sure–he can hear the difference.”

Shakey’s innovations are everywhere. Intent on controlling amp volume from his guitar instead of the amp, Young had a remote device designed called the Whizzer. Guitarists marvel at the stomp box that lies onstage at Young’s feet: a byzantine gang of effects that can be utilized without any degradation to the original signal. Just constructing the box’s angular red wooden housing to Young’s extreme specifications had craftsmen pulling their hair out.

Cradled in a stand in front of the amps is the fuse for the dynamite, Young’s trademark ax–Old Black, a ’53 Gold Top Les Paul some knothead daubed with black paint eons ago. Old Black’s features include a Bigsby wang bar, which pulls strings and bends notes, and a Firebird pickup so sensitive you can talk through it. It’s a demonic instrument. “Old Black doesn’t sound like any other guitar,” said Cragg, shaking his head.

For Cragg, Old Black is a nightmare. Young won’t permit the ancient frets to be changed, likes his strings old and used, and the Bigsby causes the guitar to go out of tune constantly. “At sound check, everything will work great. Neil picks up the guitar, and for some reason that’s when things go wrong.”

Recenzii

“Jimmy McDonough’s fat, teeming, obsessive, and revelatory biography of Young is a pure shot of all-access pleasure. . . . Hugely original.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Just as unmanageable, hard-headed, overzealous, and ultimately endearing as Young himself . . . A maddening, beguiling portrait of an elusive maverick . . . A glorious mess.” —San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

“An exhilarating match-up of author and subject makes Shakey a great, gripping read. . . . A must-read for anyone who cares about Neil Young.” —Rolling Stone

“Staggeringly thorough . . . McDonough gets it all: the chaos, the grandeur, the good times and dreary deaths, the alcohol- and drug-besotted recording sessions, the broken hearts, and the sheer unfettered joy of a seriously gifted artist.” —Salon

“The definitive book on the subject.” —The Washington Post

“Exhaustive, quarrelsome, and sometimes maddening . . . there are revelations in abundance.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Where the average rock-star biography is a tepid, toothless thing, McDonough has approached his task like a literary Terminator, steaming ahead with lethal thoroughness. One of the most penetrative studies of a rock icon ever written.” —Times (London)

“A mammoth portrait of the artist and lively exhumation of rock n roll history. . . . [McDonough] traces a rich turbulent career in vivid detail.” —The New York Times

“Imaginatively written...not only is Shakey an extraordinary literary feat of research and affection and endurance, it's an insight into the art of biography itself.”—Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“Delves further into the life and motives of one of music's most private individuals than anything previously released. . . surprisingly comprehensive and thoroughly enjoyable. . . .The most detailed portrait of this shrouded artist to date.” —San Jose Mercury News

“Exhaustively researched, impressively detailed. . . The long passages in which McDonough steps aside to let Young talk are the most revealing. ‘One day I'm a jerk,’ Young says, ‘the next day I'm a genius.’ This book argues artfully for the latter.”—People

“Like meeting Brando's Kurtz in a cave at the end of Apocalypse Now. . . . Young comes across as a Jekyll-and-Hyde loner whose life has unfolded like a reckless chemistry experiment -- a control freak on an endless quest for the uncontrolled moment.” —Macleans (Canada)

“McDonough is an avid fan, music critic and impartial journalist all in one. . . . [He] deftly weaves Young's life, actions and art together. . . . What was known of Young's life before was akin to a series of rough demos. In Shakey, McDonough delivers a full double-album.” —Rocky Mountain News

“Does what most rock bios don’t: It fails to fawn, it delivers the juice, it subjects the hero to the scrutiny and disappointment of a fan. . . A page-turning good read..”—Houston Chronicle

“Fascinating reading. . . McDonough gives us as good a look at [Young’s] cards as we’re likely to get.” —The Tampa Tribune

“[Shakey's] unprecedented access makes for an entertaining read: McDonough, more than any music journalist since Peter Guralnick in his authoritative Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, has succeeded in stripping a star of his iconography.”—The Observer (London)

“Crammed with razor-sharp insights and mind-boggling detail, Shakey is a rock-solid literary triumph, as inspired and inspiring as the eccentric figure it evokes with such frustrated devotion.” — The Guardian (London)

“McDonough . . . pores through Young’s life with vivid prose and blunt detail, and he is unashamed to insert some stinging opinions. In his probing conversations with Young, . . . he challenges the formidable artist in ways that few others would dare.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“It’s hard to imagine anyone trying to better this book. . . It has what Young values above all else. . . passion.”—Evening Standard (London)

“Just as unmanageable, hard-headed, overzealous, and ultimately endearing as Young himself . . . A maddening, beguiling portrait of an elusive maverick . . . A glorious mess.” —San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

“An exhilarating match-up of author and subject makes Shakey a great, gripping read. . . . A must-read for anyone who cares about Neil Young.” —Rolling Stone

“Staggeringly thorough . . . McDonough gets it all: the chaos, the grandeur, the good times and dreary deaths, the alcohol- and drug-besotted recording sessions, the broken hearts, and the sheer unfettered joy of a seriously gifted artist.” —Salon

“The definitive book on the subject.” —The Washington Post

“Exhaustive, quarrelsome, and sometimes maddening . . . there are revelations in abundance.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Where the average rock-star biography is a tepid, toothless thing, McDonough has approached his task like a literary Terminator, steaming ahead with lethal thoroughness. One of the most penetrative studies of a rock icon ever written.” —Times (London)

“A mammoth portrait of the artist and lively exhumation of rock n roll history. . . . [McDonough] traces a rich turbulent career in vivid detail.” —The New York Times

“Imaginatively written...not only is Shakey an extraordinary literary feat of research and affection and endurance, it's an insight into the art of biography itself.”—Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“Delves further into the life and motives of one of music's most private individuals than anything previously released. . . surprisingly comprehensive and thoroughly enjoyable. . . .The most detailed portrait of this shrouded artist to date.” —San Jose Mercury News

“Exhaustively researched, impressively detailed. . . The long passages in which McDonough steps aside to let Young talk are the most revealing. ‘One day I'm a jerk,’ Young says, ‘the next day I'm a genius.’ This book argues artfully for the latter.”—People

“Like meeting Brando's Kurtz in a cave at the end of Apocalypse Now. . . . Young comes across as a Jekyll-and-Hyde loner whose life has unfolded like a reckless chemistry experiment -- a control freak on an endless quest for the uncontrolled moment.” —Macleans (Canada)

“McDonough is an avid fan, music critic and impartial journalist all in one. . . . [He] deftly weaves Young's life, actions and art together. . . . What was known of Young's life before was akin to a series of rough demos. In Shakey, McDonough delivers a full double-album.” —Rocky Mountain News

“Does what most rock bios don’t: It fails to fawn, it delivers the juice, it subjects the hero to the scrutiny and disappointment of a fan. . . A page-turning good read..”—Houston Chronicle

“Fascinating reading. . . McDonough gives us as good a look at [Young’s] cards as we’re likely to get.” —The Tampa Tribune

“[Shakey's] unprecedented access makes for an entertaining read: McDonough, more than any music journalist since Peter Guralnick in his authoritative Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, has succeeded in stripping a star of his iconography.”—The Observer (London)

“Crammed with razor-sharp insights and mind-boggling detail, Shakey is a rock-solid literary triumph, as inspired and inspiring as the eccentric figure it evokes with such frustrated devotion.” — The Guardian (London)

“McDonough . . . pores through Young’s life with vivid prose and blunt detail, and he is unashamed to insert some stinging opinions. In his probing conversations with Young, . . . he challenges the formidable artist in ways that few others would dare.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“It’s hard to imagine anyone trying to better this book. . . It has what Young values above all else. . . passion.”—Evening Standard (London)

Descriere

The long-awaited, exhaustive and controversial biography of one of rock 'n roll's towering figures is filled with direct, never-before-published words from Neil Young himself. of photos.