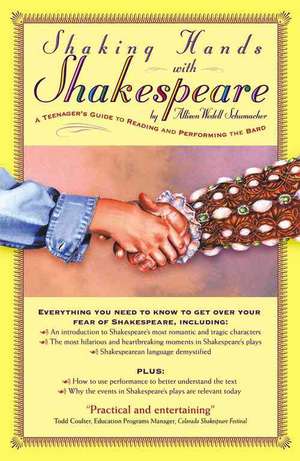

Shaking Hands with Shakespeare: A Teenager's Guide to Reading and Performing the Bard

Autor Allison Schumacheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 aug 2004

*Shakespeare's language

*Acting Shakespeare

*Going to see Shakespeare

*Sections on the four types of Shakespeare plays, Shakespeare's characters, great moments in Shakespeare plays, famous lines, and more

Preț: 55.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 83

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.56€ • 11.03$ • 8.74£

10.56€ • 11.03$ • 8.74£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743246835

ISBN-10: 0743246837

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Kaplan Publishing

Colecția Kaplan Publishing

ISBN-10: 0743246837

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Kaplan Publishing

Colecția Kaplan Publishing

Cuprins

Table of Contents About the Author

Section One: Meeting Shakespeare: History and Language

Section One: Meeting Shakespeare: History and Language

Chapter One: Shakespeare, His Theatre, and His Times: A Quick Overview

Chapter Two: Shakespeare's Language: Say What?!Section Two: Studying Shakespeare: Plays and Characters

Chapter Three: The Four Types of Plays Chapter Four: Shakespeare's Characters: Strong Women, Tragic Heroes, and Evil VillainsSection Three: Performing Shakespeare: Actors and Audiences

Chapter Five: Great Moments: Shakespeare's Dilemmas, Hoaxes, and Romances

Chapter Six: Acting Shakespeare Chapter Seven: Going to See Shakespeare: Why It Is Not Like Watching TVSection Four: Appendices

Appendix A: Famous Lines from Shakespeare Appendix B: An Annotated List of Shakespeare's Plays on Film

Appendix C: ACTivities Listed

Appendix D: Glossary

Appendix E: Works Consulted 207

Extras

Chapter One: Shakespeare, His Theatre, and His Times: A Quick Overview 'Tis a chronicle of day by day.

-- The Tempest, Act V, Scene i, Line 191

JUST THE FACTS, MA'AM

Think about all the things we know about famous people these days. For instance, take the Hollywood filmmaker Steven Spielberg. Of course, you already know what he does for a living. But how hard would it be to find out where and when he was born? Or find out how many kids he has, and what their names are? Easy, right?

Believe it or not, those basic facts are pretty much all we know about the life of the famous 16th-century English playwright, William Shakespeare.

If you really wanted to, you could delve deeper into Spielberg's life and background just by doing a little bit of research on the Internet or by watching tapes of the many interviews he's done over the years. In addition to all of the things mentioned above, you could readily find out other intimate details such as how he got his start, what kinds of things inspire his work, etc.

But with Shakespeare, we don't have that option. In fact, we don't know very much about him at all. Here are all the things we know for certain:

Connecting the Dots

Unfortunately, we will have to be content with those basic facts. Based on those facts, however, and upon inferences derived from his plays and sonnets, many people have made educated guesses about Shakespeare's life. While these are informed decisions based on extensive research of the period in which he lived, they are really only conjecture. Here are some of the speculations that Shakespearean scholars and biographers have made about his life:

Most scholars think that Shakespeare was an actor before he was a playwright. Once he started writing, however, his plays consumed much of his time. If you were a playwright in Elizabethan England, you would either be associated with a specific theatre company, like Shakespeare was, or you would be a freelance playwright. You might have a little more artistic freedom as a freelance playwright, but with a company, you would have a more dependable paycheck. If you belonged to a company who depended on your work for their livelihood, you would probably have a contract with the company that stated how many plays you had to write per year and how much you would get paid for each of them. This would mean that you would have to deliver your manuscripts on time so that the actors would have something to show to the public when the time came. For most of your career, you would need to write two plays per year, like Shakespeare did.

One advantage to belonging to a single company for his entire career was that Shakespeare got to know the actors really well and could tailor characters to their specific skills. Most actors tended to play one character type. Types would include kings, clowns, or ingénues, for instance, and so if Shakespeare were writing a play with a king in it, he would keep in mind the actor in his company who most often played kings. As a result, a relationship was formed that was beneficial to all: Shakespeare had good actors to provide him with inspiration and character development, and in return, the actors achieved fame by skillfully portraying roles that were designed just for them.

Once Shakespeare finished writing a play, it had to be approved by a government official called the Master of Revels, who was a censor. Elizabethan England did not have the freedom of speech that we enjoy today, and so part of the Master of Revels' job was to take out all the parts that might express moral, religious, or political opinions that he felt the public should not hear. The Master of Revels then gave the playwright permission to produce the play publicly; this was called licensing.

Sides

If the play was written by hand, and there was only one copy of it, how did all the players learn their lines? Once the play was censored and licensed, the script was given to a member of the theatre company called the prompter. The prompter would take the only existing copy of the play and, instead of writing out an entire copy for every member of the cast, he would give each cast member a small booklet or scroll called a side, which contained only that character's lines and cues. It was a cheaper and more efficient way to make sure everyone learned his lines: First, paper and ink were expensive, and second, there was no such thing as a copy machine, so all copying had to be done by hand. There were printing presses, but having a script printed out just for the players would have been an unnecessarily expensive and time-consuming undertaking. To ensure that the actor would know when to say each line, his side might also contain cues or prompts, which would be the last few words of the line that came before it.

Sources

Shakespeare got ideas for plots and stories from a lot of different places. In Elizabethan England, there were no copyright laws, so copying other people's work or using it without permission was a pretty common practice. Shakespeare borrowed plots, situations, and characters from many different sources, including history, mythology, legend, fiction, other plays, and the Bible. Sometimes he used several different sources and wove them all into one play. Of course, he changed what he wanted or needed to change, making the stories uniquely his own, and yet Elizabethan audiences were happy to see characters and stories they recognized. We'll discuss specific sources for plays in chapter three.

Shakespeare's Times: Elizabethan England

There were a lot of changes going on in England during Shakespeare's lifetime. England was finally establishing itself as a major European power and was enjoying great cultural and economic advances. Perhaps the biggest change of all, though, was the fact that England had a female ruler, Queen Elizabeth. She was born in 1533, and became the queen in 1558, which means she had already been ruling England for six years by the time Shakespeare was born. Kings and queens of England were said to rule by divine right. In other words, people believed that the royal bloodline had been anointed by God to be the ruling family of England. However, many people thought Queen Elizabeth should get married so that they could have a proper king. But Elizabeth knew that if she did marry, she would be giving up most of her power to her husband, and so she chose instead to remain "The Virgin Queen."

The English people believed in what they called a Chain of Being: Everything in the universe belonged in one long chain, organized in order of importance. God was at the top of this chain, of course, followed by Queen Elizabeth, the nobility, priests, and bishops of the church, gentlemen (people with titles), commoners, beggars, and slaves. No matter where they were on the chain, men were thought to be superior to women. So, you can see why people found it difficult to accept the concept of having a queen ruling over them, rather than a king.

As a result, Queen Elizabeth had a lot to prove. She had to show that she was just as good at running the empire as any man. In 1588, the English Navy defeated the Spanish Armada, a group of warships sent by King Philip II of Spain, who thought that Elizabeth should not be on the throne because she was female and because she had chosen to be Protestant rather than Catholic. Because of this great and rather unexpected defeat, the English finally felt that they had established themselves as a military power. And even though Queen Elizabeth herself had very little to do with the actual battle plans, the English Navy's victory helped boost her popularity with her subjects.

In fact, Elizabeth turned out to be a very successful queen. When she became queen, England was heavily in debt and was torn by political and religious disagreements. It had a weak military and was at the whim of its two major enemies, France and Spain. Plus, England was a very uneducated and poor nation. But Elizabeth made a lot of improvements. She supported commerce and trade, bringing England out of debt and raising the standard of living. She brought her people together in common support of her. She made England into a strong military force, and supported the efforts of historians and of explorers such as Sir Walter Raleigh, who founded the colony of Virginia in America and named it after Elizabeth, his Virgin Queen. She supported education, founding colleges and making sure most towns had elementary schools. Indeed, Queen Elizabeth's reign was unusually long and prosperous.

Elizabethan Beliefs

Religion

Although Elizabethan England was a very religious society, non-religious ways of thinking were becoming more prevalent in England than ever before. On the one hand, Elizabethans were deeply religious, and believed that everything they did in their daily lives on earth would determine whether they went to heaven or hell. They were required by law to attend church every Sunday and to take communion three times a year, or they would have to pay a fine. (It was not long before this that people had believed that it was a sin to study anything, such as science, that did not have to do with Christianity.)

But at the same time, a movement called humanism was gaining acceptance. Humanists felt that learning about classical studies (the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans) could be as worthy a pursuit as the study of the Bible. In other words, they felt that goodness and knowledge could come from human beings without the aid of a divine being. Even though they may not have consciously defined their beliefs this way, many Elizabethans believed in both Christianity and humanism at the same time, although they might seem contradictory.

There was no longer just one type of Christian, either, and this was becoming a problem. A major debate was raging between the Protestants and the Catholics. Elizabeth's father, King Henry VIII, had broken away from Catholicism to form his own Protestant church, the Church of England. There was still a lot of controversy over this situation. Most of the rest of Europe was still Catholic, and there were many English people who believed that Henry had been wrong to leave the Catholic Church. It was not until Henry's daughter, Queen Elizabeth, came to the throne that Protestantism became the accepted form of Christian worship in England. For the most part, she managed to unite her people in support of the Church of England. Of course, there were still Catholics in England, but they had to worship in secret, because they were sometimes punished or even killed for disagreeing with the government's choice of religion.

Freedom of Speech

Although there was no freedom of speech as we know it today, writers of the time could still create dissent against the government if they did not agree with its political or religious views. Queen Elizabeth was aware of the fact that plays could sway the general public.

In fact, in 1601, one of Shakespeare's plays was used for just such a purpose. Robert Devereaux, second Earl of Essex, wanted the throne for himself, and he was pretty sure he could get it by convincing some of Queen Elizabeth's supporters to endorse him instead. So one of Essex's friends, Sir Gelli Meyrick, convinced Shakespeare and his company to perform Richard II. Why this particular play? Richard II is about a monarch whose popularity is declining and whose cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, very much wanted to be King himself. Bolingbroke manages to gain the support of most of the public and forces Richard to give up the throne to him. Because of the play's obvious parallels to the situation Elizabeth now found herself in with Essex, Meyrick thought Richard II would be just the thing to convince the public that they should join Essex against Queen Elizabeth. Shakespeare and his company put on the play with great reluctance, as Elizabeth had been a great supporter of Shakespeare's work and he was very grateful for it. As it turned out, Essex's uprising quickly lost steam, as most of the public remained loyal to the queen. Essex was arrested, tried, and beheaded for his trouble.

However, Queen Elizabeth wasn't taking any chances. It was because of the danger of episodes just like this that she insisted that playwrights should not be allowed to write about religious or political subjects. As a safeguard, she had the Master of Revels go through each manuscript and take out anything political or religious.

Without religious subject matter, many playwrights turned to classical subjects, which meant that humanism had a chance to flourish in the Elizabethan theatre. As a result, deep and devoted religious beliefs stood side by side with an interest in secular subjects and pastimes in every Elizabethan's life.

Elizabethan Entertainment

Elizabethans enjoyed a wide range of entertainment. Built beside Shakespeare's theatre, the Globe, was a building called Paris Gardens. Paris Gardens was an arena where people could go to see bear- and bull-baiting. The bear or bull was chained to a wall or other immobile object, and dogs were allowed to tease and "bait" it while the spectators looked on. If the bear or bull were able to kill one of the dogs, another dog was simply released in its place. Occasionally, a blinded bear was chained up and five or six men would stand around it and whip it.

Another popular Elizabethan pastime was cockfighting, in which two roosters were made to fight to the death in a pit while observers watched and made bets as to which would win. (Clearly, "cruelty to animals" was not yet a phrase that had any meaning to the Elizabethans.)

Cockfighting and bear-baiting were the theatre's main competition for the public's attention, so theatre companies had to make sure that they delivered what the public wanted to see. This was one reason they so often contracted with playwrights, so that they would have a constant stream of new material to show their patrons.

Fortunately for the theatre companies, Queen Elizabeth very much enjoyed the theatre in general and Shakespeare's work in particular. But the Queen would never come out to the theatre among the common people to see a play. Instead, she made the theatre come to her. She would summon a company of players to her court, have her carpenters erect a stage in the great hall, and have the theatre company perform a play or two of her choosing. This usually happened during the Christmas holidays in the evening, which meant the great hall had to be lit with candles and torches (remember that the light bulb wouldn't be invented for another two hundred years or so), which was an expensive undertaking. Documentation shows that Shakespeare's theatre company -- called the Lord Chamberlain's Men because they were financially supported by a nobleman called the Lord Chamberlain -- performed for Queen Elizabeth at her court at least 32 times.

Queen Elizabeth was also a great fan and supporter of music, both secular and religious. Composers of both secular and religious music flourished under her protection. She was responsible for the rise in popularity of chamber music. Because of her, it became fashionable for those who could afford it to build a special room, or "chamber," just for music to be played in. She employed a 32-piece orchestra at her court, and began putting on free concerts to the public, so that even the poorest of her subjects could enjoy an afternoon of musical entertainment.

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Poverty and Plague

Although Queen Elizabeth was responsible for improving the general economy of England, the various classes seemed to get even further apart. In many cases, the rich got richer while the poor got poorer. Homeless beggars were very common, as there was no system in place to take care of them. Epidemic diseases such as the plague were still prevalent, even though the worst of the plague was over. But since the black (or bubonic) plague was a disease spread by fleas from rats, London -- a dirty, crowded city -- was the perfect place for it to thrive. During Shakespeare's lifetime, the plague took about 75,000 lives. Given that the total population of London was 200,000 at the time, this was a huge loss. Although the Elizabethans did not know what caused the plague or how to cure it, they did figure out that it was very contagious. As a result, the theatres were closed during times of plague. Any house where a person had died of plague was locked up for a month, and the door was painted with a red cross and the words "Lord have mercy upon us."

Because poverty was so widespread, crime was a constant danger. Pickpockets were everywhere, and people were advised not to travel at night, whether in the country or in the city. Some of the richer people hired bodyguards. When thieves and murderers were caught, the punishment was severe. Public whippings and brandings were not uncommon, and executions were generally done by beheading or hanging. More minor offenders were left in the stocks (boards with holes for their heads and hands) in public squares, sometimes for days at a time, where passersby could taunt them or throw garbage at them.

Elizabethan Households

In a typical Elizabethan household there wasn't much time to relax, because all the work had to be done during daylight hours. Houses were generally small -- only one or two rooms -- so rooms often had more than one use. For instance, when it was time for a meal, a board was set up on supports to make a table. This is why the word "board" came to be synonymous with "meal," as in the expression "room and board." Stools were placed around the table for diners to sit, although if there were more people than stools, the adults were allowed to sit and the young children generally had to stand at the table for the meal. Most people did not bother with plates; instead, large, thick, stale pieces of bread (called "trenchers") were used. Those who could afford them did use plates, although they were square rather than round, which is how the expression "a square meal" came about. Forks were only just coming into use; instead, people used spoons or their hands.

The main dish was almost always meat, often two or three kinds. On any given day, you might see beef, veal, pork, chicken, lamb, mutton (meat from an adult sheep), rabbit, or goat served at the dinner table. The meat often had an elaborate sauce to hide the flavor, because animals were generally slaughtered in the fall and the meat barreled for use throughout the year. (You can imagine that it would not taste very good by the time spring came around!) There was the occasional vegetable, such as cabbage or turnips, and fruit, fruit pies, or cheese for dessert. The Elizabethans especially loved sweets, and chocolate (as well as the tomato) was introduced from the New World during Elizabeth's reign. Because clean, good-tasting water was scarce, adults and children alike drank beer or wine made from grapes, apples or other fruits, or honey.

Elizabethan houses often did not have floorboards, but instead had dirt floors. To make the place smell cleaner, they would cover the floor in rushes (or "threshes") and place a board (or "threshold") at the bottom of the doorway to keep the threshes from falling out into the street.

Most houses didn't have windows in the modern sense, because glass was scarce and expensive. They did, however, place small holes, perhaps six inches square, in the wall near the ceiling, where extra smoke from the cooking fire could escape and natural light could come in. Since these holes also let in the wind, they came to be called "wind holes," or "windows."

An Elizabethan house did not have much in the way of furniture. A family would often sleep together in the same room. If they owned a bed, it was generally reserved for the adults. A bed consisted of a wooden frame with interlacing ropes across it, on top of which a hay-stuffed mattress was laid. The ropes would generally loosen over time, causing the mattress to sag, and would therefore have to be tightened periodically. Since a bed was more comfortable when the ropes were tight, the phrase "sleep tight" was coined to mean "have a good sleep."

Shakespeare's Theatre

In Shakespeare's time, theatre was very different than it is today, beginning with the architecture. Shakespeare's Globe Theatre, for instance, was circular, with an open space in the middle. The stage was on one edge of the circle and was what is known as a thrust, that is, there were playgoers on three sides, as if the stage had been "thrust" out into the audience. The stage had two levels. The first level of the stage was where most of the action took place, and the second story, called the gallery, was used for things like balcony scenes (as in Romeo and Juliet) or fairy worlds (as in A Midsummer Night's Dream). Sometimes, musicians sat in the gallery to provide background music or sound effects, such as birdcalls and thunder. Occasionally, when the gallery was not being used by musicians or players, noblemen or other prominent people were allowed to sit there. Of course, this meant they were looking down on the actors' heads and the view was not all that good. However, being seen by everyone else was more important to them than seeing the play themselves.

The rest of the circular theatre was three stories high, with benches where the audience could sit (it cost a bit more if you wanted a cushion for the wooden seat); these were called galleries. There was an open space called a yard or a pit in the middle of the circle in front of the stage, where other audience members could stand. A ticket for the seated part of the theatre cost twice as much as a ticket to stand in the yard, because patrons could sit down and be sheltered from sun and rain. As a result, the poorer theatre patrons tended to be the ones standing on the ground to watch the plays and were therefore called groundlings. They sometimes stood a long time, as plays lasted up to four hours. In all, the Globe could hold about 3,000 people.

Unlike other theatres, the Globe was owned by the theatre company that used it. Most theatre companies had to rent space every time they wanted to produce a play, and, as a result, they were never sure where they would be because this differed according to what space was available and what they could afford at the time. The Globe, however, was owned by several different people, including Shakespeare. They were called shareholders, and all were members of the Lord Chamberlain's Men. Having their own theatre meant that they had a permanent home in London, and no longer needed to tour their shows to make money. As their reputation grew, people knew they could go to the Globe and be assured of seeing good entertainment.

Costumes

One of the biggest expenses for a theatre company was costumes and props. The Elizabethan concept of costuming was different than it is today. For one thing, the Elizabethans had very little knowledge of how people dressed before their time. So, even in plays that portrayed historical subject matter (such as Julius Caesar, which takes place in ancient Rome, or Henry IV, which takes place in England in 1402-03, almost two centuries before Shakespeare wrote the play), the actors would have been dressed in contemporary Elizabethan attire instead of in period costume. Nonetheless, theatre companies took great care to costume their characters lavishly, and a lot of money was spent obtaining and maintaining costumes.

The actors wore what is called court dress.

If an Elizabethan were lucky enough to be invited to the Queen's court for a visit, he would dress in the very best clothes he owned, and this type of clothing was what actors used onstage. The modern equivalent would be seeing a play with all the actors dressed in tuxedos or evening gowns.

That does not mean that all the actors looked alike on stage. Small accessories, called props, were used to aid in the audience's understanding of various characters. For instance, an actor playing a knight might have worn part or all of a suit of armor and carried a sword, whereas a queen might have been given a crown to wear and an elaborate, fancy chair to sit in.

Scenery

One thing the Elizabethan theatre did not have was scenery. Believe it or not, the concept had not really occurred to anyone -- at least, not in the form we know it today. If a scene took place in a forest, it is not as if someone had painted an elaborate backdrop of trees. If a scene took place in an alehouse, there was no bar or kegs of ale. Instead, audiences knew where the action was taking place because of the dialogue, and they were expected to use their imaginations to picture the setting.

There was no shortage of special effects at the Globe Theatre, however. The stage was equipped with a trap door so that characters such as devils or ghosts could seem to disappear or rise up. There was flying apparatus so that fairies or gods could float above the stage or descend from the sky. There were special tables that made it look like a decapitated body was lying next to its severed head (there were holes in the table top for two actors -- one whose head was below the surface of the table, and one whose head was above). There were musicians to provide birdcalls with flutes and thunder with drums. If blood were needed on stage, an actor would carry a sponge soaked in vinegar or other red liquid in the appropriate spot in his costume and squeeze it at just the right time during a swordfight.

Audience

When you go to see a play today, you sit in one seat and do not move until intermission or the end of the play. When the lights go down, that is your cue to stop talking, so that you and your fellow audience members can concentrate on the action of the play. Food and drink are usually not allowed in the theatre.

When you go to see a football game today, you can get up and down from your seat as often as you want. You know the game is starting because loud music begins to play. You can discuss the action with your friends and even yell at the players on the field if you do not think that they are doing a good job. You can eat and drink as much as you want.

Believe it or not, being an audience member of the theatre in Shakespeare's time was more like going to see a modern-day football game. As mentioned before, the plays took place in the afternoon, usually starting at two o'clock. The Globe was an open-air theatre, so audience members could see each other clearly, see what others were wearing and whom they had come with, wave to and chat with their friends, etc. A trumpeter would sound several blasts on his horn to signal the start of the play. Once the play began, audience members could move freely about the yard or the galleries, discuss the action of the play amongst themselves, and yell funny quips or insults to the characters onstage. Occasionally, if they did not like the play that was being presented, they would throw things, such as fruit or even wood, until they got their way. In addition, there were people moving about the crowd selling food such as apples, pears, and nuts; and even wine, ale, tobacco, and playbills were available for purchase.

All this makes it sound as though Elizabethan audiences never really paid attention when they came to see plays, which is not true. Given how many theatres there were in London at the time and how many new plays Shakespeare and his contemporaries were having to churn our per year to meet the public demand, it is clear that theatre was a popular and beloved pastime of Elizabethans, and Shakespeare was at the forefront of that trend.

Copyright © 2004 by Kaplan, Inc.

-- The Tempest, Act V, Scene i, Line 191

JUST THE FACTS, MA'AM

Think about all the things we know about famous people these days. For instance, take the Hollywood filmmaker Steven Spielberg. Of course, you already know what he does for a living. But how hard would it be to find out where and when he was born? Or find out how many kids he has, and what their names are? Easy, right?

Believe it or not, those basic facts are pretty much all we know about the life of the famous 16th-century English playwright, William Shakespeare.

If you really wanted to, you could delve deeper into Spielberg's life and background just by doing a little bit of research on the Internet or by watching tapes of the many interviews he's done over the years. In addition to all of the things mentioned above, you could readily find out other intimate details such as how he got his start, what kinds of things inspire his work, etc.

But with Shakespeare, we don't have that option. In fact, we don't know very much about him at all. Here are all the things we know for certain:

BAPTISM: William Shakespeare was baptized at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon (named so because the town of Stratford sits on the Avon River), England, on April 26, 1564. HOUSE: Shakespeare bought a big house called New Place in Stratford in 1597. Although he lived in London off and on for the rest of his life, he never sold New Place, and his family most likely lived there full-time.Not much, is it? All the things we know about the man otherwise known as the Bard of Avon are kind of boring. It would be much more interesting if we knew more personal details. Did he write his plays at home or at a pub over a pint of ale? How did he become interested in theatre in the first place? Is there any connection between the grief over the death of his son Hamnet and the creation of the sad and tortured character Hamlet five or six years later?

MARRIAGE: On November 28, 1582, Shakespeare was issued a marriage license allowing him to marry Anne Hathaway. He was eighteen and she was twenty-six. She was also pregnant with their first child.

CHILDREN: Shakespeare and his wife had three children. Susanna was born in 1583, and their twins, Hamnet and Judith, were born in 1585. Hamnet died in 1596, when he was only 11 years old.

BUSINESS: Along with other players, or actors, Shakespeare formed a theatre company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men in 1594 and became an owner of the Globe Theatre in 1599. He bought quite a bit of land in the Stratford area and invested in a house in London. He once testified in a court case in London.

WILL: In early 1616, Shakespeare wrote his will, leaving his "second-best bed" to his wife (no one knows why, nor what happened to his very best bed), some money and other items to his daughter Judith, and most of the rest of his estate to his daughter Susanna and her husband. He also left some money to three of the actors in his company: Richard Burbage, John Heminge, and Henry Condell.

DEATH: Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616, and was buried near the chancel of Holy Trinity Church, where he had been baptized.

Connecting the Dots

Unfortunately, we will have to be content with those basic facts. Based on those facts, however, and upon inferences derived from his plays and sonnets, many people have made educated guesses about Shakespeare's life. While these are informed decisions based on extensive research of the period in which he lived, they are really only conjecture. Here are some of the speculations that Shakespearean scholars and biographers have made about his life:

BIRTH: We do not know his exact birth date, but babies in Elizabethan England were usually baptized only days after their birth, so scholars have generally agreed that his date of birth was April 23. Probably the most compelling reason for this decision, however, is that he died on April 23. He could have been born as late as the 25th or as early as the 19th, but it just seems more poetic to suppose that he died on his birthday. HOBBIES: Many people think Shakespeare had an interest in falconry because a falcon appears on his family's coat of arms and because there are numerous references to the sport in his plays.SHAKESPEARE THE PLAYWRIGHT

SCHOOL: The grammar school (or elementary school) in Stratford was called the King's New School. Since William Shakespeare's father John was mayor of Stratford at the time, Shakespeare would have qualified to attend school there. There are no student records or class lists, so we have no way of knowing if he actually went there. Keep in mind, though, that most people in Shakespeare's time (including Shakespeare's own father) could not read or write, so Shakespeare had to have gone to school somewhere in order to become not only literate, but eventually a great playwright, too. Another clue: Shakespeare's work contains numerous references to books that were only printed in Latin, and at the time, grammar schools taught as much Latin as they did English. The King's New School seems like the most logical place where Shakespeare might have received his education.

TRAVEL: The general agreement is that Shakespeare never left England, because, although many of his plays take place in distant lands (Denmark, Rome, Venice, etc.), his geography is generally pretty far off the mark. For instance, his characters may travel from one place to another in a day when, in reality, it would have taken three days, and he would set cities by the sea which are actually landlocked. On the other hand, many writers bend the truth to suit their purposes when writing fiction. It is possible that Shakespeare went to some or all of the places he wrote about and simply chose to change them.

Most scholars think that Shakespeare was an actor before he was a playwright. Once he started writing, however, his plays consumed much of his time. If you were a playwright in Elizabethan England, you would either be associated with a specific theatre company, like Shakespeare was, or you would be a freelance playwright. You might have a little more artistic freedom as a freelance playwright, but with a company, you would have a more dependable paycheck. If you belonged to a company who depended on your work for their livelihood, you would probably have a contract with the company that stated how many plays you had to write per year and how much you would get paid for each of them. This would mean that you would have to deliver your manuscripts on time so that the actors would have something to show to the public when the time came. For most of your career, you would need to write two plays per year, like Shakespeare did.

One advantage to belonging to a single company for his entire career was that Shakespeare got to know the actors really well and could tailor characters to their specific skills. Most actors tended to play one character type. Types would include kings, clowns, or ingénues, for instance, and so if Shakespeare were writing a play with a king in it, he would keep in mind the actor in his company who most often played kings. As a result, a relationship was formed that was beneficial to all: Shakespeare had good actors to provide him with inspiration and character development, and in return, the actors achieved fame by skillfully portraying roles that were designed just for them.

Once Shakespeare finished writing a play, it had to be approved by a government official called the Master of Revels, who was a censor. Elizabethan England did not have the freedom of speech that we enjoy today, and so part of the Master of Revels' job was to take out all the parts that might express moral, religious, or political opinions that he felt the public should not hear. The Master of Revels then gave the playwright permission to produce the play publicly; this was called licensing.

Sides

If the play was written by hand, and there was only one copy of it, how did all the players learn their lines? Once the play was censored and licensed, the script was given to a member of the theatre company called the prompter. The prompter would take the only existing copy of the play and, instead of writing out an entire copy for every member of the cast, he would give each cast member a small booklet or scroll called a side, which contained only that character's lines and cues. It was a cheaper and more efficient way to make sure everyone learned his lines: First, paper and ink were expensive, and second, there was no such thing as a copy machine, so all copying had to be done by hand. There were printing presses, but having a script printed out just for the players would have been an unnecessarily expensive and time-consuming undertaking. To ensure that the actor would know when to say each line, his side might also contain cues or prompts, which would be the last few words of the line that came before it.

Sources

Shakespeare got ideas for plots and stories from a lot of different places. In Elizabethan England, there were no copyright laws, so copying other people's work or using it without permission was a pretty common practice. Shakespeare borrowed plots, situations, and characters from many different sources, including history, mythology, legend, fiction, other plays, and the Bible. Sometimes he used several different sources and wove them all into one play. Of course, he changed what he wanted or needed to change, making the stories uniquely his own, and yet Elizabethan audiences were happy to see characters and stories they recognized. We'll discuss specific sources for plays in chapter three.

Shakespeare's Times: Elizabethan England

There were a lot of changes going on in England during Shakespeare's lifetime. England was finally establishing itself as a major European power and was enjoying great cultural and economic advances. Perhaps the biggest change of all, though, was the fact that England had a female ruler, Queen Elizabeth. She was born in 1533, and became the queen in 1558, which means she had already been ruling England for six years by the time Shakespeare was born. Kings and queens of England were said to rule by divine right. In other words, people believed that the royal bloodline had been anointed by God to be the ruling family of England. However, many people thought Queen Elizabeth should get married so that they could have a proper king. But Elizabeth knew that if she did marry, she would be giving up most of her power to her husband, and so she chose instead to remain "The Virgin Queen."

The English people believed in what they called a Chain of Being: Everything in the universe belonged in one long chain, organized in order of importance. God was at the top of this chain, of course, followed by Queen Elizabeth, the nobility, priests, and bishops of the church, gentlemen (people with titles), commoners, beggars, and slaves. No matter where they were on the chain, men were thought to be superior to women. So, you can see why people found it difficult to accept the concept of having a queen ruling over them, rather than a king.

As a result, Queen Elizabeth had a lot to prove. She had to show that she was just as good at running the empire as any man. In 1588, the English Navy defeated the Spanish Armada, a group of warships sent by King Philip II of Spain, who thought that Elizabeth should not be on the throne because she was female and because she had chosen to be Protestant rather than Catholic. Because of this great and rather unexpected defeat, the English finally felt that they had established themselves as a military power. And even though Queen Elizabeth herself had very little to do with the actual battle plans, the English Navy's victory helped boost her popularity with her subjects.

In fact, Elizabeth turned out to be a very successful queen. When she became queen, England was heavily in debt and was torn by political and religious disagreements. It had a weak military and was at the whim of its two major enemies, France and Spain. Plus, England was a very uneducated and poor nation. But Elizabeth made a lot of improvements. She supported commerce and trade, bringing England out of debt and raising the standard of living. She brought her people together in common support of her. She made England into a strong military force, and supported the efforts of historians and of explorers such as Sir Walter Raleigh, who founded the colony of Virginia in America and named it after Elizabeth, his Virgin Queen. She supported education, founding colleges and making sure most towns had elementary schools. Indeed, Queen Elizabeth's reign was unusually long and prosperous.

Elizabethan Beliefs

Religion

Although Elizabethan England was a very religious society, non-religious ways of thinking were becoming more prevalent in England than ever before. On the one hand, Elizabethans were deeply religious, and believed that everything they did in their daily lives on earth would determine whether they went to heaven or hell. They were required by law to attend church every Sunday and to take communion three times a year, or they would have to pay a fine. (It was not long before this that people had believed that it was a sin to study anything, such as science, that did not have to do with Christianity.)

But at the same time, a movement called humanism was gaining acceptance. Humanists felt that learning about classical studies (the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans) could be as worthy a pursuit as the study of the Bible. In other words, they felt that goodness and knowledge could come from human beings without the aid of a divine being. Even though they may not have consciously defined their beliefs this way, many Elizabethans believed in both Christianity and humanism at the same time, although they might seem contradictory.

There was no longer just one type of Christian, either, and this was becoming a problem. A major debate was raging between the Protestants and the Catholics. Elizabeth's father, King Henry VIII, had broken away from Catholicism to form his own Protestant church, the Church of England. There was still a lot of controversy over this situation. Most of the rest of Europe was still Catholic, and there were many English people who believed that Henry had been wrong to leave the Catholic Church. It was not until Henry's daughter, Queen Elizabeth, came to the throne that Protestantism became the accepted form of Christian worship in England. For the most part, she managed to unite her people in support of the Church of England. Of course, there were still Catholics in England, but they had to worship in secret, because they were sometimes punished or even killed for disagreeing with the government's choice of religion.

Freedom of Speech

Although there was no freedom of speech as we know it today, writers of the time could still create dissent against the government if they did not agree with its political or religious views. Queen Elizabeth was aware of the fact that plays could sway the general public.

In fact, in 1601, one of Shakespeare's plays was used for just such a purpose. Robert Devereaux, second Earl of Essex, wanted the throne for himself, and he was pretty sure he could get it by convincing some of Queen Elizabeth's supporters to endorse him instead. So one of Essex's friends, Sir Gelli Meyrick, convinced Shakespeare and his company to perform Richard II. Why this particular play? Richard II is about a monarch whose popularity is declining and whose cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, very much wanted to be King himself. Bolingbroke manages to gain the support of most of the public and forces Richard to give up the throne to him. Because of the play's obvious parallels to the situation Elizabeth now found herself in with Essex, Meyrick thought Richard II would be just the thing to convince the public that they should join Essex against Queen Elizabeth. Shakespeare and his company put on the play with great reluctance, as Elizabeth had been a great supporter of Shakespeare's work and he was very grateful for it. As it turned out, Essex's uprising quickly lost steam, as most of the public remained loyal to the queen. Essex was arrested, tried, and beheaded for his trouble.

However, Queen Elizabeth wasn't taking any chances. It was because of the danger of episodes just like this that she insisted that playwrights should not be allowed to write about religious or political subjects. As a safeguard, she had the Master of Revels go through each manuscript and take out anything political or religious.

Without religious subject matter, many playwrights turned to classical subjects, which meant that humanism had a chance to flourish in the Elizabethan theatre. As a result, deep and devoted religious beliefs stood side by side with an interest in secular subjects and pastimes in every Elizabethan's life.

Elizabethan Entertainment

Elizabethans enjoyed a wide range of entertainment. Built beside Shakespeare's theatre, the Globe, was a building called Paris Gardens. Paris Gardens was an arena where people could go to see bear- and bull-baiting. The bear or bull was chained to a wall or other immobile object, and dogs were allowed to tease and "bait" it while the spectators looked on. If the bear or bull were able to kill one of the dogs, another dog was simply released in its place. Occasionally, a blinded bear was chained up and five or six men would stand around it and whip it.

Another popular Elizabethan pastime was cockfighting, in which two roosters were made to fight to the death in a pit while observers watched and made bets as to which would win. (Clearly, "cruelty to animals" was not yet a phrase that had any meaning to the Elizabethans.)

Cockfighting and bear-baiting were the theatre's main competition for the public's attention, so theatre companies had to make sure that they delivered what the public wanted to see. This was one reason they so often contracted with playwrights, so that they would have a constant stream of new material to show their patrons.

Fortunately for the theatre companies, Queen Elizabeth very much enjoyed the theatre in general and Shakespeare's work in particular. But the Queen would never come out to the theatre among the common people to see a play. Instead, she made the theatre come to her. She would summon a company of players to her court, have her carpenters erect a stage in the great hall, and have the theatre company perform a play or two of her choosing. This usually happened during the Christmas holidays in the evening, which meant the great hall had to be lit with candles and torches (remember that the light bulb wouldn't be invented for another two hundred years or so), which was an expensive undertaking. Documentation shows that Shakespeare's theatre company -- called the Lord Chamberlain's Men because they were financially supported by a nobleman called the Lord Chamberlain -- performed for Queen Elizabeth at her court at least 32 times.

Queen Elizabeth was also a great fan and supporter of music, both secular and religious. Composers of both secular and religious music flourished under her protection. She was responsible for the rise in popularity of chamber music. Because of her, it became fashionable for those who could afford it to build a special room, or "chamber," just for music to be played in. She employed a 32-piece orchestra at her court, and began putting on free concerts to the public, so that even the poorest of her subjects could enjoy an afternoon of musical entertainment.

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Poverty and Plague

Although Queen Elizabeth was responsible for improving the general economy of England, the various classes seemed to get even further apart. In many cases, the rich got richer while the poor got poorer. Homeless beggars were very common, as there was no system in place to take care of them. Epidemic diseases such as the plague were still prevalent, even though the worst of the plague was over. But since the black (or bubonic) plague was a disease spread by fleas from rats, London -- a dirty, crowded city -- was the perfect place for it to thrive. During Shakespeare's lifetime, the plague took about 75,000 lives. Given that the total population of London was 200,000 at the time, this was a huge loss. Although the Elizabethans did not know what caused the plague or how to cure it, they did figure out that it was very contagious. As a result, the theatres were closed during times of plague. Any house where a person had died of plague was locked up for a month, and the door was painted with a red cross and the words "Lord have mercy upon us."

Because poverty was so widespread, crime was a constant danger. Pickpockets were everywhere, and people were advised not to travel at night, whether in the country or in the city. Some of the richer people hired bodyguards. When thieves and murderers were caught, the punishment was severe. Public whippings and brandings were not uncommon, and executions were generally done by beheading or hanging. More minor offenders were left in the stocks (boards with holes for their heads and hands) in public squares, sometimes for days at a time, where passersby could taunt them or throw garbage at them.

Elizabethan Households

In a typical Elizabethan household there wasn't much time to relax, because all the work had to be done during daylight hours. Houses were generally small -- only one or two rooms -- so rooms often had more than one use. For instance, when it was time for a meal, a board was set up on supports to make a table. This is why the word "board" came to be synonymous with "meal," as in the expression "room and board." Stools were placed around the table for diners to sit, although if there were more people than stools, the adults were allowed to sit and the young children generally had to stand at the table for the meal. Most people did not bother with plates; instead, large, thick, stale pieces of bread (called "trenchers") were used. Those who could afford them did use plates, although they were square rather than round, which is how the expression "a square meal" came about. Forks were only just coming into use; instead, people used spoons or their hands.

The main dish was almost always meat, often two or three kinds. On any given day, you might see beef, veal, pork, chicken, lamb, mutton (meat from an adult sheep), rabbit, or goat served at the dinner table. The meat often had an elaborate sauce to hide the flavor, because animals were generally slaughtered in the fall and the meat barreled for use throughout the year. (You can imagine that it would not taste very good by the time spring came around!) There was the occasional vegetable, such as cabbage or turnips, and fruit, fruit pies, or cheese for dessert. The Elizabethans especially loved sweets, and chocolate (as well as the tomato) was introduced from the New World during Elizabeth's reign. Because clean, good-tasting water was scarce, adults and children alike drank beer or wine made from grapes, apples or other fruits, or honey.

Elizabethan houses often did not have floorboards, but instead had dirt floors. To make the place smell cleaner, they would cover the floor in rushes (or "threshes") and place a board (or "threshold") at the bottom of the doorway to keep the threshes from falling out into the street.

Most houses didn't have windows in the modern sense, because glass was scarce and expensive. They did, however, place small holes, perhaps six inches square, in the wall near the ceiling, where extra smoke from the cooking fire could escape and natural light could come in. Since these holes also let in the wind, they came to be called "wind holes," or "windows."

An Elizabethan house did not have much in the way of furniture. A family would often sleep together in the same room. If they owned a bed, it was generally reserved for the adults. A bed consisted of a wooden frame with interlacing ropes across it, on top of which a hay-stuffed mattress was laid. The ropes would generally loosen over time, causing the mattress to sag, and would therefore have to be tightened periodically. Since a bed was more comfortable when the ropes were tight, the phrase "sleep tight" was coined to mean "have a good sleep."

Shakespeare's Theatre

In Shakespeare's time, theatre was very different than it is today, beginning with the architecture. Shakespeare's Globe Theatre, for instance, was circular, with an open space in the middle. The stage was on one edge of the circle and was what is known as a thrust, that is, there were playgoers on three sides, as if the stage had been "thrust" out into the audience. The stage had two levels. The first level of the stage was where most of the action took place, and the second story, called the gallery, was used for things like balcony scenes (as in Romeo and Juliet) or fairy worlds (as in A Midsummer Night's Dream). Sometimes, musicians sat in the gallery to provide background music or sound effects, such as birdcalls and thunder. Occasionally, when the gallery was not being used by musicians or players, noblemen or other prominent people were allowed to sit there. Of course, this meant they were looking down on the actors' heads and the view was not all that good. However, being seen by everyone else was more important to them than seeing the play themselves.

The rest of the circular theatre was three stories high, with benches where the audience could sit (it cost a bit more if you wanted a cushion for the wooden seat); these were called galleries. There was an open space called a yard or a pit in the middle of the circle in front of the stage, where other audience members could stand. A ticket for the seated part of the theatre cost twice as much as a ticket to stand in the yard, because patrons could sit down and be sheltered from sun and rain. As a result, the poorer theatre patrons tended to be the ones standing on the ground to watch the plays and were therefore called groundlings. They sometimes stood a long time, as plays lasted up to four hours. In all, the Globe could hold about 3,000 people.

Unlike other theatres, the Globe was owned by the theatre company that used it. Most theatre companies had to rent space every time they wanted to produce a play, and, as a result, they were never sure where they would be because this differed according to what space was available and what they could afford at the time. The Globe, however, was owned by several different people, including Shakespeare. They were called shareholders, and all were members of the Lord Chamberlain's Men. Having their own theatre meant that they had a permanent home in London, and no longer needed to tour their shows to make money. As their reputation grew, people knew they could go to the Globe and be assured of seeing good entertainment.

Costumes

One of the biggest expenses for a theatre company was costumes and props. The Elizabethan concept of costuming was different than it is today. For one thing, the Elizabethans had very little knowledge of how people dressed before their time. So, even in plays that portrayed historical subject matter (such as Julius Caesar, which takes place in ancient Rome, or Henry IV, which takes place in England in 1402-03, almost two centuries before Shakespeare wrote the play), the actors would have been dressed in contemporary Elizabethan attire instead of in period costume. Nonetheless, theatre companies took great care to costume their characters lavishly, and a lot of money was spent obtaining and maintaining costumes.

The actors wore what is called court dress.

If an Elizabethan were lucky enough to be invited to the Queen's court for a visit, he would dress in the very best clothes he owned, and this type of clothing was what actors used onstage. The modern equivalent would be seeing a play with all the actors dressed in tuxedos or evening gowns.

That does not mean that all the actors looked alike on stage. Small accessories, called props, were used to aid in the audience's understanding of various characters. For instance, an actor playing a knight might have worn part or all of a suit of armor and carried a sword, whereas a queen might have been given a crown to wear and an elaborate, fancy chair to sit in.

Scenery

One thing the Elizabethan theatre did not have was scenery. Believe it or not, the concept had not really occurred to anyone -- at least, not in the form we know it today. If a scene took place in a forest, it is not as if someone had painted an elaborate backdrop of trees. If a scene took place in an alehouse, there was no bar or kegs of ale. Instead, audiences knew where the action was taking place because of the dialogue, and they were expected to use their imaginations to picture the setting.

There was no shortage of special effects at the Globe Theatre, however. The stage was equipped with a trap door so that characters such as devils or ghosts could seem to disappear or rise up. There was flying apparatus so that fairies or gods could float above the stage or descend from the sky. There were special tables that made it look like a decapitated body was lying next to its severed head (there were holes in the table top for two actors -- one whose head was below the surface of the table, and one whose head was above). There were musicians to provide birdcalls with flutes and thunder with drums. If blood were needed on stage, an actor would carry a sponge soaked in vinegar or other red liquid in the appropriate spot in his costume and squeeze it at just the right time during a swordfight.

Audience

When you go to see a play today, you sit in one seat and do not move until intermission or the end of the play. When the lights go down, that is your cue to stop talking, so that you and your fellow audience members can concentrate on the action of the play. Food and drink are usually not allowed in the theatre.

When you go to see a football game today, you can get up and down from your seat as often as you want. You know the game is starting because loud music begins to play. You can discuss the action with your friends and even yell at the players on the field if you do not think that they are doing a good job. You can eat and drink as much as you want.

Believe it or not, being an audience member of the theatre in Shakespeare's time was more like going to see a modern-day football game. As mentioned before, the plays took place in the afternoon, usually starting at two o'clock. The Globe was an open-air theatre, so audience members could see each other clearly, see what others were wearing and whom they had come with, wave to and chat with their friends, etc. A trumpeter would sound several blasts on his horn to signal the start of the play. Once the play began, audience members could move freely about the yard or the galleries, discuss the action of the play amongst themselves, and yell funny quips or insults to the characters onstage. Occasionally, if they did not like the play that was being presented, they would throw things, such as fruit or even wood, until they got their way. In addition, there were people moving about the crowd selling food such as apples, pears, and nuts; and even wine, ale, tobacco, and playbills were available for purchase.

All this makes it sound as though Elizabethan audiences never really paid attention when they came to see plays, which is not true. Given how many theatres there were in London at the time and how many new plays Shakespeare and his contemporaries were having to churn our per year to meet the public demand, it is clear that theatre was a popular and beloved pastime of Elizabethans, and Shakespeare was at the forefront of that trend.

Copyright © 2004 by Kaplan, Inc.