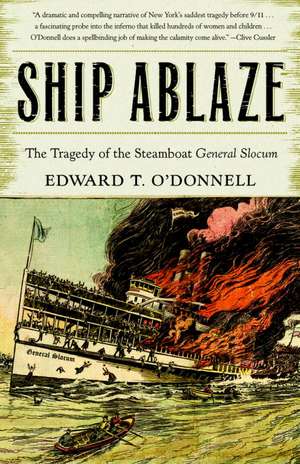

Ship Ablaze: The Tragedy of the Steamboat General Slocum

Autor Edward T. O'Donnellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2004

Preț: 118.73 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 178

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.72€ • 23.77$ • 18.87£

22.72€ • 23.77$ • 18.87£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767909068

ISBN-10: 0767909062

Pagini: 332

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767909062

Pagini: 332

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Edward T. O’Donnell is an associate professor of American history at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. He is the author of 1001 Things Everyone Should Know About Irish American History (Broadway Books, 2002). He lives in Holden, Massachusetts, with his wife, Stephanie, and four daughters, Erin, Kelly, Michelle, and Katherine (and their dog, Sammy). To learn more, please visit his Web site: www.EdwardTODonnell.com.

Extras

The Captain

He awoke to the same familiar sounds as on every morning--the creak and groan of a wooden vessel at pier, the persistent lap, lap, lap of water against the hull, the squawk of a seagull, the peal of a distant ship whistle. Dawn was breaking over the Hudson River, and another day of furious maritime activity was about to begin.

It was still dark as the captain rolled off his bunk, dressed, and stepped out on the deck of his boat. The air was cold, but it being June 14, there was a noticeable springlike hint in it. Out across the frigid, seemingly motionless river he could see the sources of the morning's first sounds. Dark silhouettes of tugs and barges moved in the distance, punctuated here and there by colored lanterns. Seagulls stood on the ship railings and soared overhead looking for the first sign of breakfast. Closer by, the captain saw row upon row of boats at pier, most dark and silent as though sleeping, but a few like his with lantern light streaming from a cabin window.

Captain William Van Schaick, like a lot of old-time unmarried captains, lived aboard his boat. He did so less because of some romantic love of the sea and more to simply save money. At sixty-seven years of age, retirement was not far off and he needed to save every penny of his $37.50 per week salary if he wanted to avoid living out his last days in poverty. He still paid rent, but less than half the going rate for a Manhattan apartment. Plus you couldn't beat the commute.

The onset of warm weather meant his busy season was upon him. From late May to early October he'd work nearly every day as New Yorkers clambered aboard his boat on group outings to the shore and day trips to see the big yacht races. Today was the eighth charter excursion of the young season for him. He'd been at it now for more years than he cared to remember, including the last thirteen on this steamboat, the General Slocum. In fact, he had been the only captain the steamer had ever known.

Tethered to a long, weatherbeaten pier, the steamboat rolled gently back and forth with the silent rhythms of waves left by passing vessels. In the faint predawn light then beginning to brighten the sky over the Hudson, the steamer General Slocum presented an imposing, dark silhouette. Unlike many of its fellow passenger steamers, many of which began their careers in other port cities like Boston, Providence, or Newport, the General Slocum was a New York boat through and through. It was built by the Devine Burtis shipbuilding firm in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn in 1890-91. Miss May Lewis, niece of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company's president, joined a large crowd of spectators on the day of the launch in April 1891. Moments after she broke a bottle across its bow, the steamboat slid down the ways into the chilly waters of New York harbor.

As befitting a locally built boat destined to ply local waterways, the Knickerbocker Steamboat Co. named it for Maj. Gen. Henry Warner Slocum (1827-94). A graduate of West Point, Slocum had served with distinction in the Union Army, including commands at Gettysburg and with Sherman's scorched-earth march to the sea across Georgia. Slocum parlayed his military record into a successful law practice and three terms in Congress between 1869 and 1885. Affixing the name of this much-

admired elder statesman to the paddle box in large fancy lettering would, the owners hoped, lend the new steamboat an aura of respectability, honor, glory, and history.

The steamer itself, however, conveyed a very different image. The moment its sharp hull sliced into the chilly waters of New York harbor on that cold spring morning in 1891, there was no question which passenger steamer stood supreme. No steamboat in and around New York could compare with the General Slocum in terms of design and luxurious appointments. At 264 feet in length and weighing 1,281 tons, the Slocum was not the largest boat of its kind in the harbor. Even its sister ship, the Grand Republic, was longer. But its sleek, wooden hull that swept gracefully upward from stern to prow indicated a steamboat designed for both speed and elegance as well as size. As was the custom of the day, the Slocum's hull was painted a brilliant white. Above it the three stacked decks, cabin walls, rails, doors, and benches were varying shades of brown varnished wood.

The Slocum's interior was likewise designed to provide up to twenty-five hundred passengers with a maximum of luxury and comfort. Two large open rooms called "saloons" on the lower and middle decks provided passengers with wicker chairs upholstered in fine red velvet and tables at which they could enjoy good things to eat from the kitchen and bar. Lush carpeting, fine paintings, wood carvings, and ornate light fixtures here and elsewhere in the boat's several lounges added to its ambience. Abundant windows allowed for a maximum of natural light and fresh air. For those who wanted more of both, there was the vast upper or "hurricane" deck, some ten thousand square feet of open space enclosed only by a three-foot-high railing. Towering above it all stood two large side-by-side smokestacks painted a flat yellow.

In 1891 no steamboat in New York could equal the Slocum's beauty and opulence. Nor could any steamboat match its combination of speed, size, and maneuverability. Deep inside the boat's hull, beneath the decks devoted to the needs and whims of the passengers, lay the enormous steam-powered engine built by the W. & A. Fletcher Company in Hoboken, New Jersey. Attached to it were two massive paddle wheels mounted on both sides of the boat. Each was nine feet wide, thirty-one feet in diameter, and studded with twenty-six paddles. With the engine running at full throttle, they could claw the water with such ferocity that the steamer reached the astonishing speed of fifteen knots. Even still, speed and size did not compromise maneuverability, for the Slocum was fitted with an ultramodern steam-powered steering system.

None of this was possible, of course, without steam. One deck below the W. & A. Fletcher engine were two huge boilers and an entire hold compartment full of several tons of coal. The age of steamboat travel had dawned nearly a century ago on the very waters where the Slocum now floated. In 1807, Robert Fulton became the first person to successfully apply steam power to a boat when he piloted the Clermont 150 miles up the Hudson River to Albany. Fulton's triumph announced the arrival of the industrial age, when new technology would allow man to defy nature--in this case, the relentless downward flow of a major river. More precisely, it ushered in a new era, decades before the railroad, of steam-propelled travel. And with each passing decade, subsequent inventors and engineers made enormous improvements in steamboat power, efficiency, speed, and safety. By the time of the General Slocum's launch in 1891, massive steam-driven ocean liners routinely crossed the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, carrying thousands of passengers and tons of cargo.

Much of the Slocum's mechanical format was visible for all to see. Mounted amidships just aft of the smokestacks stood a tall steel tower surmounted by a diamond-shaped lever. Attached to one end of the lever was the engine's twenty-foot-high piston rod. Attached to the lever's other end were two drive rods that led to the paddle wheels (see diagram). As the rhythmic pulses of steam from the boiler caused the piston rod to move upward and downward six feet in each direction, it moved the lever, which in turn moved the wheels. Despite its deceptively simple appearance, it was a highly complex system of energy generation and transfer, the product of more than two centuries of refinement in engineering.

For its first five seasons the General Slocum enjoyed a reputation as one of the city's finest passenger steamers. On weekends and holidays from late May to early October, it made two round-trips from Manhattan to Rockaway, a popular seaside retreat in outermost Queens on Long Island. At fifty cents for a round-trip, New Yorkers of every class enjoyed the two and a half hours (75 minutes each way) about the commodious Slocum almost as much as the intervening time at the beach. On weekdays and special occasions such as the annual international yacht races off Sandy Hook, groups paid top dollar to charter the steamboat.

But in that era of incessant advancements in technology and cutthroat competition between passenger lines, the Slocum's reign as the city's top steamer was short-lived. What had been cutting-edge technology and the very latest in first-class appointments in 1891 were by the mid-1890s rather unexceptional. Newer, bigger, faster steamboats with far more luxurious accommodations such as full dining rooms, lounges, and dance floors now commanded the attention--and dollars--of the city's swell set. By 1896 the Slocum had slipped to the second-tier rankings of steamboats, still very respectable and profitable, yet considerably less so than the day she went into service. The boat rarely sat idle during the peak season, only now it was chartered by middle- and working-class groups like unions, fraternal societies, and churches.

Today it was the latter, a church group bound for Empire Grove on Long Island Sound. An hour after the captain awoke, the steamer buzzed with activity as the crew prepared it for the excursion. Tons of coal and water were brought aboard along with ample food, drink, and ice. Deckhands spiffed up the boat's appearance using mops and rags and then hosed the whole boat down. Most crews used their own boat's fire hose and pump for this morning ritual, but not on the Slocum. For as long as anyone could remember, they had used a hose and hydrant from the pier. And it was just as well, for anyone could see that the Slocum's weathered fire hoses were not up to the task.

It took only fifteen minutes or so to complete the wash-down. Cloudy gray torrents of water spilled from the boat's scuppers, carrying away layers of salt, seagull droppings, coal soot, and traces of fine cork dust. The latter fell every day from the twenty-five hundred tattered life preservers slowly disintegrating in their racks above the decks. Minutes later, the deckhands cast off lines and the Slocum headed down the Hudson River to a pier where more than a thousand passengers awaited, eagerly anticipating a day of fun at the shore, safe from the dangers of the city.

Empire City

Not long after the Slocum glided down the Hudson for its scheduled rendezvous with its church group, a ferry pulled away from its landing in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey. Jammed to the rails with rush-hour commuters, the craft moved slowly through the brackish water. In twenty minutes it would reach the landing on the Lower West Side of Manhattan, deposit its cargo of hundreds, and return for another load. Every morning hundreds of thousands of men and women of every profession and class made their way to the Empire City in this manner over the harbor, or across the Hudson and East Rivers. Every evening the process was reversed as dozens of ferries slowly drained off a sizable portion of Manhattan's workforce, taking them to their homes in Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and New Jersey.

Most of the passengers on the ferry that morning lived permanently outside of Manhattan. But it being June 14 and the beginning of the summer season, some were professional men commuting from summer cottages rented for one or more weeks along the Jersey Shore. Among them was George B. McClellan, Jr., the mayor of New York City and son of the controversial Civil War general of the same name. Commuting to his office at city hall via the Hudson River ferry was an entirely new experience for him. Only yesterday he and his wife had moved into a seaside cottage at Long Branch for the duration of the summer and early fall. The idea had been his wife's, for she was worried that the mounting stress from the day-to-day rigors of office would ruin his health. They could certainly afford it on McClellan's annual salary of fifteen thousand dollars. As an added plus, the move would give them a chance to mix with the finest kind of New York society, since in the words of one guidebook, "The Branch" had been "for many years the most fashionable summer resort in the vicinity of New York." Residents of the area's fine hotels and private cottages, the guide continued, divided their days between "bathing in the morning, driving in the afternoon, and dancing in the evening."

At thirty-nine, McClellan, known as Max to his friends, was one of the youngest men to occupy the mayor's office. Born in late 1865 while his parents were in Dresden during a three-and-a-half-year tour of Europe, he enjoyed an upbringing that was both comfortable and focused. His parents, nurses, teachers, and professors at Princeton instilled in him the habits and attitudes of an aristocrat, or what democratically inclined Americans preferred to call a gentleman. Like others of his class, he attended an Ivy League college (Princeton) where he studied history, art, and languages as well as literature, math, and science. This grooming plus a steady stream of famous personages into the McClellan household from the worlds of business and politics brought him to understand that he belonged to an American nobility, not an inherited status as in Europe, but one secured through the acquisition of wealth and training. With this status, he was informed, came certain obligations, chief among them public service. For Max, of course, there would be an additional requirement of no small magnitude--that he win the presidency and redeem the honor of the father to whom he was so devoted.

Until recently, he had seemed well on his way to doing just that. After a stint as the youngest man to serve as president of the New York City Board of Aldermen followed by several terms in Congress, McClellan's name was bandied about in 1900 as a possible Democratic nominee for vice president, perhaps even president. His youth (he was only thirty-five) and modest national profile caused the boon to fizzle, but his journey to the White House seemed only a matter of time. Three years later the gentleman politician threw caution to the wind and ran for mayor of New York. He hoped the high-profile job would give him the national exposure he needed to secure the Democratic nomination in 1904. Such a scenario seemed firmly grounded in reality, for the current occupant of the White House, Theodore Roosevelt, first gained national recognition as an anticorruption crusader while serving as New York's commissioner of police from 1895 to 1897. Four short years later he had managed to ride that fame, boosted by his "Rough Rider" exploits in Cuba in 1898, into the governor's office, the vice presidency, and, courtesy of an assassin's bullet, the White House.

From the Hardcover edition.

He awoke to the same familiar sounds as on every morning--the creak and groan of a wooden vessel at pier, the persistent lap, lap, lap of water against the hull, the squawk of a seagull, the peal of a distant ship whistle. Dawn was breaking over the Hudson River, and another day of furious maritime activity was about to begin.

It was still dark as the captain rolled off his bunk, dressed, and stepped out on the deck of his boat. The air was cold, but it being June 14, there was a noticeable springlike hint in it. Out across the frigid, seemingly motionless river he could see the sources of the morning's first sounds. Dark silhouettes of tugs and barges moved in the distance, punctuated here and there by colored lanterns. Seagulls stood on the ship railings and soared overhead looking for the first sign of breakfast. Closer by, the captain saw row upon row of boats at pier, most dark and silent as though sleeping, but a few like his with lantern light streaming from a cabin window.

Captain William Van Schaick, like a lot of old-time unmarried captains, lived aboard his boat. He did so less because of some romantic love of the sea and more to simply save money. At sixty-seven years of age, retirement was not far off and he needed to save every penny of his $37.50 per week salary if he wanted to avoid living out his last days in poverty. He still paid rent, but less than half the going rate for a Manhattan apartment. Plus you couldn't beat the commute.

The onset of warm weather meant his busy season was upon him. From late May to early October he'd work nearly every day as New Yorkers clambered aboard his boat on group outings to the shore and day trips to see the big yacht races. Today was the eighth charter excursion of the young season for him. He'd been at it now for more years than he cared to remember, including the last thirteen on this steamboat, the General Slocum. In fact, he had been the only captain the steamer had ever known.

Tethered to a long, weatherbeaten pier, the steamboat rolled gently back and forth with the silent rhythms of waves left by passing vessels. In the faint predawn light then beginning to brighten the sky over the Hudson, the steamer General Slocum presented an imposing, dark silhouette. Unlike many of its fellow passenger steamers, many of which began their careers in other port cities like Boston, Providence, or Newport, the General Slocum was a New York boat through and through. It was built by the Devine Burtis shipbuilding firm in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn in 1890-91. Miss May Lewis, niece of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company's president, joined a large crowd of spectators on the day of the launch in April 1891. Moments after she broke a bottle across its bow, the steamboat slid down the ways into the chilly waters of New York harbor.

As befitting a locally built boat destined to ply local waterways, the Knickerbocker Steamboat Co. named it for Maj. Gen. Henry Warner Slocum (1827-94). A graduate of West Point, Slocum had served with distinction in the Union Army, including commands at Gettysburg and with Sherman's scorched-earth march to the sea across Georgia. Slocum parlayed his military record into a successful law practice and three terms in Congress between 1869 and 1885. Affixing the name of this much-

admired elder statesman to the paddle box in large fancy lettering would, the owners hoped, lend the new steamboat an aura of respectability, honor, glory, and history.

The steamer itself, however, conveyed a very different image. The moment its sharp hull sliced into the chilly waters of New York harbor on that cold spring morning in 1891, there was no question which passenger steamer stood supreme. No steamboat in and around New York could compare with the General Slocum in terms of design and luxurious appointments. At 264 feet in length and weighing 1,281 tons, the Slocum was not the largest boat of its kind in the harbor. Even its sister ship, the Grand Republic, was longer. But its sleek, wooden hull that swept gracefully upward from stern to prow indicated a steamboat designed for both speed and elegance as well as size. As was the custom of the day, the Slocum's hull was painted a brilliant white. Above it the three stacked decks, cabin walls, rails, doors, and benches were varying shades of brown varnished wood.

The Slocum's interior was likewise designed to provide up to twenty-five hundred passengers with a maximum of luxury and comfort. Two large open rooms called "saloons" on the lower and middle decks provided passengers with wicker chairs upholstered in fine red velvet and tables at which they could enjoy good things to eat from the kitchen and bar. Lush carpeting, fine paintings, wood carvings, and ornate light fixtures here and elsewhere in the boat's several lounges added to its ambience. Abundant windows allowed for a maximum of natural light and fresh air. For those who wanted more of both, there was the vast upper or "hurricane" deck, some ten thousand square feet of open space enclosed only by a three-foot-high railing. Towering above it all stood two large side-by-side smokestacks painted a flat yellow.

In 1891 no steamboat in New York could equal the Slocum's beauty and opulence. Nor could any steamboat match its combination of speed, size, and maneuverability. Deep inside the boat's hull, beneath the decks devoted to the needs and whims of the passengers, lay the enormous steam-powered engine built by the W. & A. Fletcher Company in Hoboken, New Jersey. Attached to it were two massive paddle wheels mounted on both sides of the boat. Each was nine feet wide, thirty-one feet in diameter, and studded with twenty-six paddles. With the engine running at full throttle, they could claw the water with such ferocity that the steamer reached the astonishing speed of fifteen knots. Even still, speed and size did not compromise maneuverability, for the Slocum was fitted with an ultramodern steam-powered steering system.

None of this was possible, of course, without steam. One deck below the W. & A. Fletcher engine were two huge boilers and an entire hold compartment full of several tons of coal. The age of steamboat travel had dawned nearly a century ago on the very waters where the Slocum now floated. In 1807, Robert Fulton became the first person to successfully apply steam power to a boat when he piloted the Clermont 150 miles up the Hudson River to Albany. Fulton's triumph announced the arrival of the industrial age, when new technology would allow man to defy nature--in this case, the relentless downward flow of a major river. More precisely, it ushered in a new era, decades before the railroad, of steam-propelled travel. And with each passing decade, subsequent inventors and engineers made enormous improvements in steamboat power, efficiency, speed, and safety. By the time of the General Slocum's launch in 1891, massive steam-driven ocean liners routinely crossed the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, carrying thousands of passengers and tons of cargo.

Much of the Slocum's mechanical format was visible for all to see. Mounted amidships just aft of the smokestacks stood a tall steel tower surmounted by a diamond-shaped lever. Attached to one end of the lever was the engine's twenty-foot-high piston rod. Attached to the lever's other end were two drive rods that led to the paddle wheels (see diagram). As the rhythmic pulses of steam from the boiler caused the piston rod to move upward and downward six feet in each direction, it moved the lever, which in turn moved the wheels. Despite its deceptively simple appearance, it was a highly complex system of energy generation and transfer, the product of more than two centuries of refinement in engineering.

For its first five seasons the General Slocum enjoyed a reputation as one of the city's finest passenger steamers. On weekends and holidays from late May to early October, it made two round-trips from Manhattan to Rockaway, a popular seaside retreat in outermost Queens on Long Island. At fifty cents for a round-trip, New Yorkers of every class enjoyed the two and a half hours (75 minutes each way) about the commodious Slocum almost as much as the intervening time at the beach. On weekdays and special occasions such as the annual international yacht races off Sandy Hook, groups paid top dollar to charter the steamboat.

But in that era of incessant advancements in technology and cutthroat competition between passenger lines, the Slocum's reign as the city's top steamer was short-lived. What had been cutting-edge technology and the very latest in first-class appointments in 1891 were by the mid-1890s rather unexceptional. Newer, bigger, faster steamboats with far more luxurious accommodations such as full dining rooms, lounges, and dance floors now commanded the attention--and dollars--of the city's swell set. By 1896 the Slocum had slipped to the second-tier rankings of steamboats, still very respectable and profitable, yet considerably less so than the day she went into service. The boat rarely sat idle during the peak season, only now it was chartered by middle- and working-class groups like unions, fraternal societies, and churches.

Today it was the latter, a church group bound for Empire Grove on Long Island Sound. An hour after the captain awoke, the steamer buzzed with activity as the crew prepared it for the excursion. Tons of coal and water were brought aboard along with ample food, drink, and ice. Deckhands spiffed up the boat's appearance using mops and rags and then hosed the whole boat down. Most crews used their own boat's fire hose and pump for this morning ritual, but not on the Slocum. For as long as anyone could remember, they had used a hose and hydrant from the pier. And it was just as well, for anyone could see that the Slocum's weathered fire hoses were not up to the task.

It took only fifteen minutes or so to complete the wash-down. Cloudy gray torrents of water spilled from the boat's scuppers, carrying away layers of salt, seagull droppings, coal soot, and traces of fine cork dust. The latter fell every day from the twenty-five hundred tattered life preservers slowly disintegrating in their racks above the decks. Minutes later, the deckhands cast off lines and the Slocum headed down the Hudson River to a pier where more than a thousand passengers awaited, eagerly anticipating a day of fun at the shore, safe from the dangers of the city.

Empire City

Not long after the Slocum glided down the Hudson for its scheduled rendezvous with its church group, a ferry pulled away from its landing in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey. Jammed to the rails with rush-hour commuters, the craft moved slowly through the brackish water. In twenty minutes it would reach the landing on the Lower West Side of Manhattan, deposit its cargo of hundreds, and return for another load. Every morning hundreds of thousands of men and women of every profession and class made their way to the Empire City in this manner over the harbor, or across the Hudson and East Rivers. Every evening the process was reversed as dozens of ferries slowly drained off a sizable portion of Manhattan's workforce, taking them to their homes in Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and New Jersey.

Most of the passengers on the ferry that morning lived permanently outside of Manhattan. But it being June 14 and the beginning of the summer season, some were professional men commuting from summer cottages rented for one or more weeks along the Jersey Shore. Among them was George B. McClellan, Jr., the mayor of New York City and son of the controversial Civil War general of the same name. Commuting to his office at city hall via the Hudson River ferry was an entirely new experience for him. Only yesterday he and his wife had moved into a seaside cottage at Long Branch for the duration of the summer and early fall. The idea had been his wife's, for she was worried that the mounting stress from the day-to-day rigors of office would ruin his health. They could certainly afford it on McClellan's annual salary of fifteen thousand dollars. As an added plus, the move would give them a chance to mix with the finest kind of New York society, since in the words of one guidebook, "The Branch" had been "for many years the most fashionable summer resort in the vicinity of New York." Residents of the area's fine hotels and private cottages, the guide continued, divided their days between "bathing in the morning, driving in the afternoon, and dancing in the evening."

At thirty-nine, McClellan, known as Max to his friends, was one of the youngest men to occupy the mayor's office. Born in late 1865 while his parents were in Dresden during a three-and-a-half-year tour of Europe, he enjoyed an upbringing that was both comfortable and focused. His parents, nurses, teachers, and professors at Princeton instilled in him the habits and attitudes of an aristocrat, or what democratically inclined Americans preferred to call a gentleman. Like others of his class, he attended an Ivy League college (Princeton) where he studied history, art, and languages as well as literature, math, and science. This grooming plus a steady stream of famous personages into the McClellan household from the worlds of business and politics brought him to understand that he belonged to an American nobility, not an inherited status as in Europe, but one secured through the acquisition of wealth and training. With this status, he was informed, came certain obligations, chief among them public service. For Max, of course, there would be an additional requirement of no small magnitude--that he win the presidency and redeem the honor of the father to whom he was so devoted.

Until recently, he had seemed well on his way to doing just that. After a stint as the youngest man to serve as president of the New York City Board of Aldermen followed by several terms in Congress, McClellan's name was bandied about in 1900 as a possible Democratic nominee for vice president, perhaps even president. His youth (he was only thirty-five) and modest national profile caused the boon to fizzle, but his journey to the White House seemed only a matter of time. Three years later the gentleman politician threw caution to the wind and ran for mayor of New York. He hoped the high-profile job would give him the national exposure he needed to secure the Democratic nomination in 1904. Such a scenario seemed firmly grounded in reality, for the current occupant of the White House, Theodore Roosevelt, first gained national recognition as an anticorruption crusader while serving as New York's commissioner of police from 1895 to 1897. Four short years later he had managed to ride that fame, boosted by his "Rough Rider" exploits in Cuba in 1898, into the governor's office, the vice presidency, and, courtesy of an assassin's bullet, the White House.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A dramatic and compelling narrative of New York's saddest tragedy before 9/11 . . . a fascinating probe into the inferno that killed hundreds of women and children . . . O'Donnell does a spellbinding job of making the calamity come alive.”

—Clive Cussler

“An impressively written account that effectively conveys the horror of New York’s second-worst disaster ever.”

—Booklist

“Compelling . . . O’Donnell’s story is a testament to the strength of a unique people in an equally unique city . . . Unforgettable.”

—National Review

—Clive Cussler

“An impressively written account that effectively conveys the horror of New York’s second-worst disaster ever.”

—Booklist

“Compelling . . . O’Donnell’s story is a testament to the strength of a unique people in an equally unique city . . . Unforgettable.”

—National Review