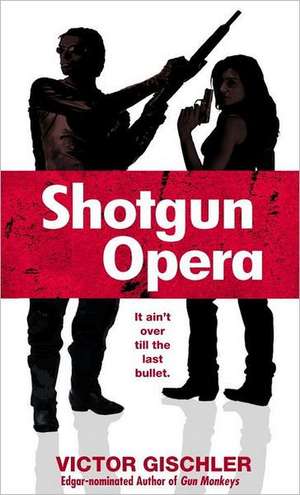

Shotgun Opera

Autor Victor Gischleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Anthony Awards (2007)

Mike’s nephew Andrew needs to disappear, and he needs to do it yesterday. Hanging with the wrong kind of friends, he’s seen something he shouldn’t have, and now he’s running for his life with an assassin on his trail. The consummate professional hit woman, Nikki Enders is the most lethal of a deadly sisterhood. And Andrew Foley is next on her extermination list. Unless Uncle Mike can stop her. As kill teams descend on Foley’s farm, one pissed-off ex—tough guy is about to take a final, all-or-nothing stand with shotguns blazing....

Preț: 32.48 lei

Preț vechi: 38.39 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 49

Preț estimativ în valută:

6.22€ • 6.65$ • 5.18£

6.22€ • 6.65$ • 5.18£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440241713

ISBN-10: 0440241715

Pagini: 305

Dimensiuni: 106 x 175 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Dell Publishing Company

ISBN-10: 0440241715

Pagini: 305

Dimensiuni: 106 x 175 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Dell Publishing Company

Notă biografică

VICTOR GISCHLER lives in the wilds of Skiatook, Oklahoma -- a long, long way from Starbuck's. His wife, Jackie, thinks he is a silly individual. He drinks black, black coffee all day long and sleeps about seven minutes a night. Victor's first novel, Gun Monkeys, was nominated for the Edgar Award.

Extras

1

Anthony Minelli, his cousin Vincent, and their pal Andrew Foley played five-card draw on a makeshift table in a nearly empty warehouse on the New York docks.

“Full house, motherfuckers. Queens over sevens.” Vincent drained the rest of his Bud Light, crumpled the can in his fat fist, and tossed it twenty feet. It clanked across the cement floor, echoed off metal walls. Vincent scooped the winnings toward his ample belly. Three dollars and nine cents.

“Nice pot,” Anthony said. “You can buy a fucking Happy Meal. Now shut up and deal.”

“Hey, it’s the skill that counts. I could be on that celebrity poker show on A&E,” Vincent said.

“Fuck you. It’s on Bravo. And you ain’t no celebrity.”

Andrew Foley smiled, reached into the Igloo cooler for one of the few remaining beers. He enjoyed the playful back and forth between the cousins but never joined in. He popped open the beer, sipped. He’d had a few already and was pretty buzzed. He’d also lost nine bucks at poker, not having won a single hand. But that was okay. Like the Minelli cousins, Andrew had been paid a cool grand for his work at the docks today. The money had come just in time.

Andrew was in his junior year at the Manhattan School of Music and he was always short on money. He was a week late on rent when Anthony had called with the offer. Andrew was well aware Anthony and Vincent were wiseguys in training and that a deal with them was sure to be a little shady. Andrew had known the two cousins since they were all in grade school. Andrew’s father and their fathers were pals. He balked at the thought of doing something illegal and maybe getting caught, but Vincent continued to assure him that the whole thing was easy money, a big fat moist piece of cake. Andrew needed cash. Period. Andrew’s landlord wasn’t a forgiving man.

Besides, it really did seem like a pretty easy job. A no-brainer really. Somebody (Just never you mind who. Don’t ask no fucking questions.) wanted a cargo container from one of the big freighter ships unloaded without going through the usual customs. This was a tall order, and a lot of people had to be bribed or distracted. Andrew, Vincent, and Anthony had a simple job. Shepherd the cargo container from the freighter to the unused warehouse way hell and gone down the other end of the wharf. The guy who’d set up the deal didn’t trust the usual union grunts to handle it, and anyway a lone cargo container getting that kind of attention would cause talk. Andrew was being overpaid enough to keep his trap shut. It was understood silence was part of the deal.

They’d forklifted the container into the warehouse and that was that. The job had seemed so simple and the guys were so giddy about their easy payday that Andrew forgot all about an overdue term paper when Anthony produced a cooler of beer and Vincent had pulled a deck of cards out of his pocket.

“What do you think is in there?” Vincent’s eyes shifted momentarily from his cards to the cargo container.

Anthony picked something out of his teeth, then said, “Drugs.”

Vincent raised an eyebrow. “Oh, yeah? You got some inside information?”

Anthony said, “It’s always drugs. Gimme two cards.”

They played cards, talked quietly, drank beer.

The little explosion rattled the warehouse. They dropped their cards and hit the floor. Andrew covered his head with his arms, his heart thumping like a rabbit’s. One of the metal doors on the cargo container creaked open. A chemical smell from the explosive hung in the air.

“Jesus H. Christ.” Anthony was the first to his feet. “What happened?”

Vincent stood up too, dusted himself off. “How the hell am I supposed to know?”

Andrew stayed on the floor, but he uncovered his head and risked a peek. Smoke in the air. Then they heard something, noise from within the container.

“Somebody’s in there,” Andrew whispered.

Vincent shook his head. “That’s fucking impossible.” He’d whispered too.

The cousins were huddled together. Andrew stood up and huddled with them. They watched the cargo container expectantly. It was like a scene in War of the Worlds, Andrew thought. The guys looking at the spaceship, waiting for the aliens to come out. They whispered at each other from the sides of their mouths.

“How could anyone breathe in there?”

“Maybe there’s more than one.”

“Illegal immigrants?”

“Should we go over there?”

“Fuck that. You go over there.”

A figure emerged from the container, and they froze.

The newcomer had dark olive skin, deep brown eyes. Black hair slicked back and dirty. A thick curly beard. He wore a stained denim shirt, threadbare tan pants. Military boots. A small pistol tucked into his waistband. Over his shoulder he carried a large brown duffel bag.

Vincent took a step forward, raised a hand. “Hey!”

Andrew put his hand on Vincent’s shoulder, held him back. What did the dumb wop think he was doing?

The stowaway jumped at the voice, then fixed Vincent with those hard dark eyes. He put his hand on the pistol in his pants, didn’t say a word. Vincent held up his hands in a “no problem here” gesture. The stowaway backed toward the door, his hand on the gun the whole time. He turned, opened the door, and exited the warehouse quickly and without a backward glance.

Anthony recovered first. “What the fuck?”

Andrew let go of Vincent’s shoulder. “What did you think you were going to do?”

Vincent looked a little pale. “Shit if I know. I just saw the guy and . . . Shouldn’t we do something?”

Andrew walked toward the container. “Let’s have a look.” The cousins followed.

The three of them stood at the door and peered inside. Dark. An odd tangle of straps and harnesses. It looked like a car seat had been arranged to withstand rough seas.

Andrew examined the container door, which had been latched from the outside. There was a small hole at the level of the latch blown outward from within, leaving the metal jagged and scorched. The guy inside had known exactly what to do to free himself.

Vincent held his nose. “What a fucking stink.”

Andrew nudged him, pointed into the corner of the container at an object that could only be a makeshift toilet. Food wrappers and other debris littered the container’s floor.

Anthony shook his head. “Oh man. We just helped smuggle some kind of Arab terrorist motherfucker. What are we going to do?”

“Not a goddamn thing,” Vincent said. “We were paid to bring the container here and keep our fucking mouths shut. We weren’t supposed to hang around and play cards. We were never meant to see this. I don’t care if that was Osama Bin Laden’s right-hand guy. We’re going to keep our fucking traps shut and not do a thing.”

Fear bloomed in Andrew’s gut, but he agreed. Maybe if he kept quiet about this, never told a soul, it would all go away.

• • •

He was known among his fellow terrorists as Jamaal 1-2-3.

He walked from the docks straight inland for five blocks, turned right, walked four blocks, then left for another three blocks. He pretended to examine shoes in a store window but was really watching the street behind him in the reflection.

No one appeared to be following him.

He zigzagged another ten minutes, found a pay phone, dropped his duffel at his feet, and dug a slip of paper out of his shirt pocket. There was a phone number. No name. No identifying markings of any kind. It was a local number, but that meant nothing. The call could be rerouted and transferred to any phone in the world. Jamaal might be calling a barbershop in the Bronx or a noodle hut in Kyoto. He dialed the number.

It rang five times before someone picked up. “Hello?”

“This is Jamaal 1-2-3.”

“One moment.” Shuffling papers. Taps at a keyboard. “What seems to be the problem?” A slight accent. Perhaps Eastern European.

“I was seen.” Jamaal explained what had happened.

“I understand.”

The voice asked Jamaal a few questions. Who were the three men? Jamaal didn’t know. What did they look like? Early twenties. American. Two with dark hair, one with lighter brown hair and pale skin. He described their clothes.

“I wasn’t supposed to be seen. If the authorities learn that—”

“It will be taken care of.”

Jamaal said, “But it’s important that—”

“I said it will be taken care of. You must go about your business. Forget the three men. Proceed as planned. Leave the rest to me.” He hung up.

The conversation’s abrupt end surprised Jamaal. He blinked, shrugged, hung up the phone. He stood there a full minute pondering his situation. His mission depended on his ability to blend into the scenery, where he would slowly go about collecting the materials he needed. And in a month or three or a year, when everything was in place, he would strike at the Great Satan for the glory of Allah. But if the American FBI or CIA knew an Arab had been smuggled into the country, they would scour the city looking for him. The witnesses had to be eliminated and quickly, before they could alert anyone.

All he could do was trust the voice on the phone and get on with his work. He shouldered the duffel and walked casually into the asphalt anonymity of New York City.

The man with the vaguely Eastern European accent had a name, but it didn’t matter what it was. He sat in a small room filled with filing cabinets and computers and fax machines and telephones. It didn’t matter where the room was. His office was the world.

He contemplated the problem of Jamaal 1-2-3.

It didn’t matter one iota to the man if Jamaal’s mission failed or not. What mattered to him was his own reputation and the fact that upset clients could be potentially dangerous. In this business, reputation was everything. He was a kind of broker. He made connections, put people with other people. Filled in gaps. He’d promised Jamaal’s organization a completely covert insertion. Now he had a mess to clean up. It was the bane of his profession that he had to rely occasionally on local people to execute the details of his operation. Now he had to send someone to make things right. Going local again would likely compound the problem. He needed someone good. He needed the best.

He picked up the phone, the special secure line, and dialed the number for the most dangerous woman in the world.

2

At that moment, in the middle of the night, the most dangerous woman in the world clung to the tiled roof of a villa in Tuscany, where she worked to circumvent the alarm system on a large skylight. If she could do that, she’d open the skylight, drop inside, and kill a Colombian named Pablo Ramirez.

For five years she had called herself Nikki Enders. This wasn’t her real name, of course, but she had a British passport and a ream of other paperwork that said she was Nikki Enders, and no one ever disputed her. She had a Swiss bank account that had millions of dollars of Nikki Enders’s money in it. Nikki Enders enjoyed a staggeringly expensive home in London, and another three-story house in the Garden District of New Orleans. She wished she could spend more time there. She also had a dozen passports in safety-deposit boxes scattered around the world and could stop being Nikki Enders at a moment’s notice.

But tonight, in Tuscany, Pablo Ramirez would run afoul of Nikki Enders.

Ramirez meant nothing to Nikki. Alive. Dead he was worth five million dollars. She didn’t know who wanted him dead or why. She didn’t care. This was simply Nikki’s job. She fumbled with a pair of alligator clips, squinted at the wires that connected the alarm system. She hated working in the dark.

The cell phone clipped to her belt vibrated against her hip. She flinched, reached back, and turned it off. She silently cursed herself. She was getting sloppy. First she’d left the night goggles behind in the hotel. Then she’d forgotten to turn off her phone. A distraction at the wrong moment might cost her in blood. She wiped the sweat off her forehead with the sleeve of her black bodysuit. She needed to calm down, get her ducks in a row.

Okay, go over the scouting report again. Ramirez had five men with him. It was a four-bedroom villa, and naturally Ramirez would claim the master suite for himself. That left the five bodyguards scattered about. They could be anywhere, sleeping, getting a snack in the kitchen. Nikki had staked out the villa earlier and saw no sign of the usual bevy of whores who kept the men entertained, so she wouldn’t catch any of them screwing. The dim illumination coming up from the skylight suggested they’d turned in for the night.

She checked her guns. The twin .380s hung from her shoulder holsters. She’d already screwed the silencers into place. There was a collapsible sniper rifle and a .40 caliber Desert Eagle strapped to the BMW motorcycle parked a block down the hill, just in case she needed something more formidable. The motorcycle was concealed under the low branches of a tree, but close enough for her to reach it quickly.

Just as she’d hoped, recalling the scouting report and rechecking her equipment helped her focus. She returned to the alarm system and the alligator clips. She fidgeted, rolled to her left, trying to readjust herself to a more comfortable position.

Floodlights flared to life, poured harsh light onto the villa’s roof. From within, a shrill alarm pulsed.

Goddammit!

There must have been some kind of roof sensor that hadn’t been in the scouting report. What should have been a stealthy execution was now going to be a gunfight. It couldn’t be helped, and she didn’t have time to hesitate.

She stood, jumped, brought her feet down hard on the skylight. The glass shattered as she fell through, the shards raining. She landed and rolled, the glass still falling, a glittering shower. She leapt up, drew the silenced automatics.

Two of the Colombians were already coming at her from one of the bedrooms. Their hair was disheveled. Boxer shorts. Sleepy eyes. But they each gripped a little Mac-10. Standard goon armament. Not original but very deadly.

The machine pistols spat fire, rattled nine-millimeter slugs six inches over Nikki’s head. The bullets shredded plaster, knocked a painting off the wall, and obliterated a lamp.

Nikki went flat, rolled along the floor, pistols stretched over her head. She squeezed the triggers, and the silencers dulled the shots to a breathy phoot. She shattered anklebone, and both men yelled and fell. When they were on the floor, she shot each of them in the top of the head.

She leapt to her feet and spun just in time to meet two bodyguards storming her from the other direction. Automatic pistols barked at her. The room filled with streaking lead.

Nikki bolted left, ducking under the fire, turn- ing to the side to make herself a small target. She jumped, fired as she flew through the air, emptying both pistols with a rapid-fire series of phoots, and landed behind an overstuffed couch. She ejected the spent magazines, slapped in new ones. She hunched low against the back of the couch as a fresh flurry of gunfire flayed the cushions. The air filled with downy couch stuffing, like a souvenir snow globe gone horribly wrong. Bullets tore through the couch an inch from Nikki’s face. Not much of a hiding place.

Nikki took a miniature flash grenade from one of her belt pouches. About the size of a golf ball. She thumbed the arming mechanism and tossed it over her shoulder. She waited for the telltale whumpf and shut her eyes against the hot stab of light. She immediately rose from behind the couch. She had to strike before the effect of the grenade faded. One of the goons had dropped his automatic, rubbed his eyes with the heels of his hands. The other had his arm over his eyes, but still waved his pistol, jerking the trigger wildly.

Nikki took him down first. Two quick shots in the chest. She spun on the other one, took three quick steps forward, and leveled her automatic a foot from his forehead. She pulled the trigger. He went stiff, flinched once, and dropped.

The room fell quiet again, the downy furniture stuffing still drifting on the air. A spent shell casing rolled along the hardwood floor.

Then the high rev of a powerful engine, the squeal of tires.

Nikki ran to the window, swept aside the curtains. A red Audi convertible erupted from the garage below her, sped toward the curving road that led down the hill, Ramirez at the wheel.

Son of a bitch!

The villa’s blueprints had been part of the scouting report. Nikki recalled the layout. The door in the kitchen, a narrow staircase that spiraled down to the garage. She ran, found the kitchen and the door. There was only the single road leading down the hill, and it was an obstacle course of switchbacks and hairpin turns. Nikki would likely be able to sprint through the neighboring yards to the motorcycle. Shouldn’t be any problem to catch up to Ramirez.

At the bottom of the staircase she burst into the garage and barely saw the tire iron coming toward her face. She brought up an arm but only partially blocked the blow, the tire iron cracking her wrist and glancing along her forehead. She stumbled back.

The goon came at her with another wild swing. She ducked underneath, kicked his kneecap, heard the fleshy pop. He screamed and went down. She finished him with a punch across the jaw. Nikki didn’t wait to see his eyes roll back. She ran from the garage, flashed across the neighbor’s lawn, and leapt aboard the BMW. She cranked it, accelerated at rocket speed down the hill without turning on the bike’s headlight.

Her wrist flared pain. Perhaps the bone was only bruised. It didn’t seem broken, but it hurt like hell. She’d been careless yet again, forgotten about the fifth bodyguard. Why couldn’t she stay focused? Maybe she was about to start her period. If a man had suggested that, she’d have broken his neck.

Nikki leaned the bike low, took a tight turn fast, and the Audi’s taillights swung into view. She thought about shooting his tires out but didn’t trust herself to handle a pistol and keep the bike steady at the same time. Not on this road at this speed. And not with an injured wrist.

With her headlight off, she didn’t think Ramirez had spotted her. On the next short straightaway, she opened the bike up full throttle, sped toward the Audi until the bike touched the rear bumper.

She leapt up on the seat, hands still tight on the handlebars as she found her balance. She launched herself and kicked the motorcycle away in the same motion. For a terrifying split second, the road flew past beneath her. Nikki landed in the back of the convertible, the motorcycle clattering and crunching along the hardpack in the Audi’s wake.

Ramirez shouted surprise, almost lost control of the Audi, tires squealing on the next turn. She wrapped one arm around his throat, her other hand going to the knife on her belt.

“Puta!” Ramirez grabbed her bad wrist, yanked her arm away from his throat.

Nikki winced, the pain lancing from her wrist up the rest of her arm. She tried to jerk away from Ramirez, but he was too strong. They careened down the road, Ramirez driving with one hand, fighting off Nikki with the other. She punched him in the back of the head. Ramirez shoved her just as he steered the Audi into a sharp turn. She tumbled out of the car, tucked into a ball, landed hard but rolled out of it. She stood, watched the taillights vanish down the road.

Godammit.

She spun, ran back up the road toward her discarded motorcycle. Nikki Enders was in top physical condition and could maintain a sprint uphill without effort. As she ran, she pictured the road, looping and snaking down the mountain. If she hurried, she’d have one more chance at Ramirez.

She arrived at the fallen bike. It was scratched and dented, a rearview mirror ripped off. She bent and pulled the sniper rifle from its sheath—almost without breaking stride. She left the road, ran up the steep hill as she unfolded the stock, and snapped the high-powered scope into place. At the top, she threw herself down in the tall grass, cocked the rifle. She looked through the scope at the road below.

She panted heavily. She forced her heart rate down. She’d need a steady hand for the shot—three hundred fifty, maybe four hundred yards. Her wrist throbbed. She ignored it.

The Audi’s headlights came around the bend. It was too dark to see Ramirez, but she aimed above the driver’s side headlight, estimated a spot on the windshield. She squeezed the trigger. The shot echoed in the night.

The Audi swerved, went off the road at high speed, and slammed into a tree. The smack and crunch of metal. She climbed down the hill to check the kill. Ramirez leaned against the steering wheel, half his head missing. Blood and brain and gunk were splattered across the backseat.

She left the Audi, continued down the hill. Neither the BMW nor any of the other equipment she left behind could be traced to her. She unclipped the cell phone from her belt and checked her recent calls to see who’d phoned. It had been him. The nameless voice on the other end of the phone who arranged all of her contracts. She hated this man—irrationally, yes, but hated him nonetheless. That she should owe her success to a faceless ghost irritated her in a way she couldn’t quite explain. Nikki Enders didn’t like having such an important aspect of her life out of her control.

She dialed his number.

“Hello.” That slight accent. Czech?

“You called?”

“Are you still on the job?” he asked.

“I just finished.”

“Good. I have something else for you.”

Nikki flexed her injured wrist. “I need some downtime.”

“I’d consider it a personal favor,” he said.

Burn in hell. “Fine. But the details need to wait. In the morning. That soon enough?”

“I’ll be waiting for your call.” He hung up.

Nikki Enders shut off her cell phone, sighed, and began the long walk back to a bland rental car safely parked in the small village at the base of the hill. Then she would drive to a prearranged safe house thirty miles away and try to sleep.

3

Mike Foley chopped wood under the blistering Oklahoma sky. Summer. Hot. The thok of the axe biting into the logs echoed off the low hills within the shallow valley. His sun-freckled skin glistened with sweat, his salt-and-pepper chest hair patchy and matted. Working his twenty acres kept him fit, but Mike was old, and tonight he’d pay for the axe work with a sore back and a handful of over-the-counter pain pills. There was too much white in his hair now. Too many lines around his eyes and mouth. His nose looked like a little apple.

It was 101 degrees outside and Mike chopped firewood and he didn’t know why. There was already enough wood stacked behind the cabin to last a hundred years, and maybe Mike just wanted to prove he could still swing the axe. Later he’d walk the row of grapevines looking for more signs that animals were at the leaves again. Deer and rabbit.

He stacked the wood, put on a short-sleeve denim shirt. The sweat had soaked dark patches at the armpits and around the neck. He grabbed his straw hat, clamped it down over his head. He went to look for Keone, the Creek Indian kid who helped him during the summer. Twelve-year-old smart-ass, but a good kid.

“Keone!”

Down one of the vine rows, the kid stuck his head out. “Boss?”

“Wait until I get on the other side, then hit the water.”

Keone flicked him a two-finger salute. The kid was thin, skin a healthy red-brown in the sun, black hair, sharp cheekbones and nose. Dark eyes but big and alert.

Mike walked down one of the long vine rows. A wooden stake hammered into the ground every thirty feet, two metal lines pulled tight between the stakes, so the vines would have something to cling to. He’d rigged up thin PVC pipe along the rows, little pinholes to let the water spray out. On the other side of the vine rows was the small barn that had come with the property, a sun-bleached wooden structure with flecks of dark green paint flaking off. Mike had poured the concrete floor himself and turned the hay barn into his winery, the big press, which he’d also built himself, and the collection of glass carboys and the hand-bottling machine and a few big vats. A little desk in the corner where he kept his books.

He was two feet from the end of the row when the PVC sputtered to life and sprayed him with water. He yelled surprise, ran ten feet, turned around, and scowled.

“Very funny, asshole.”

Keone’s high-pitched laugh floated across the wide field.

Mike threw the big barn doors open to let in air and light. He sat at the battered little desk, took one of his books from the bottom drawer. He’d bought the book on Amazon.com seven years ago. From Bunch to Bottle by Adam Openheimer was basically the complete moron’s guide to growing grapes, fermenting, and bottling. The book had saved his ass on several occasions.

When Mike had originally settled on the remote twenty acres, his intention had only been to hide from the world. In an effort to live quietly and occupy himself, he investigated what he might do with the land, rocky dry soil surrounded by gnarled oaks. Of the twenty acres, nine were on a gentle, open slope. The rest of the property consisted of thick woods or steep, rocky hillside. The soil was too piss-poor for beans or tomatoes or anything else Mike could think of growing.

So for ten years he’d hidden and sulked and watched the seasons go by, all the time living with himself and sinking into a sort of dark, hermitlike existence. And for ten years he hadn’t had a good night’s sleep, the past always there in his dreams, reminding him he couldn’t really run away from what he’d done or who he was.

An article in the Tulsa World had saved him.

A feature detailing the fledgling Oklahoma wine industry. The article led him to Oklahoma State University’s Department of Agriculture Web site, which listed the varieties of hearty grape most likely to thrive in the Okie soil and climate. The loose, rocky ground, hostile for so many different plants and vegetables, was actually good for grapes. And Mike was willing and desperate for anything to take up his time and occupy his mind.

Typically, it took three years for a vine to reach maturity and bear fruit.

I’d better get my ass in gear, Mike had thought.

And he’d purchased the stakes and the wire and a sledgehammer. He broke his back with labor and sweat that first summer, the July sun scorching him pink, then a darker red, the rocks fighting him every inch. The hobby snowballed into an obsession, and he found himself rolling out of his single bed at dawn, coffee mug in one hand, wire spool in the other. He didn’t quit until sundown. It took a month to put up ten rows. He ordered the vines from a nursery in Upstate New York and killed them because he hadn’t soaked them properly before planting. He ordered more, started over.

He found himself in a war and took it seriously. Oklahoma baked the vines in the dry summer. Winter flayed the land with ice. And slowly, over the days, he forgot to think, forgot to dwell on the past or even to look very far ahead. There were only the sun and water and weeds to pull and leaves to check and vines to prune.

He considered it work. He didn’t think of himself as one with Mother Earth or any kind of other hippie bullshit. It was long, hard work and that was all. And he wanted to do it right. He slept, so bone-weary, hands raw, dirt under his fingernails. He slept and slept and never dreamed.

The first crop of grapes had been feeble. The next crop a little better, enough for a hundred bottles of wine, which he corked and stored for a year, then poured out after tasting a glass and nearly throw- ing up.

It got better. Slowly, he learned.

Three years ago, he’d sold five hundred bottles of his first batch of drinkable wine. He called it Scorpion Hill Red. A very plain table wine, not too dry. Local stores in Oklahoma and Kansas and a few in north Texas had agreed to stock it on a regular basis. Store owners told him customers liked the label, a simple black silhouette of a scorpion against a parchment-colored background. Simple yet cheeky.

With some luck, Mike would ship ten thousand bottles next year.

He craned his neck, tried to spot Keone through the barn door. Sometimes he felt he really had to keep an eye on the kid. Once, Keone had lost control of the little tractor and flattened an entire row of ripe grapes. In a fury, he’d chased the kid with a thick switch, but Keone was too fast. It was a week before he’d shown his face at the vineyard again.

Mike couldn’t see the kid, but didn’t hear anything being demolished, so he turned his attention back to the book. He’d read it cover to cover ten times, knew what it would say, but always consulted it anyway. Always go by the book. Mike was a stickler. Follow the steps.

The book told him to spread deodorant soap shavings among the vines. The “smell of people” would keep the animals away. He was ready. He slid open the top desk drawer, took out two bars of Dial and a penknife. Later, he’d walk the perimeter. Right now, he just wanted a drink.

He went to the secondhand refrigerator in the corner of the barn, opened it, perused the beer selection. He had a few different brands. He liked beer.

Mike Foley absolutely hated the taste of wine.

On a hot day like this he’d need something light, a dark or even an amber would make him sluggish. He grabbed a Coors Light, popped the top, slurped. What was the old joke about canoes and Coors Light? Fucking close to water.

He’d just finished the first beer and thought about opening another, when Keone walked into the barn. He had something cupped in his hands.

“Freeze,” Mike shouted.

Keone froze.

“What are you bringing in here? It’s another goddamn spider, isn’t it?” One thing Mike had learned his first month in the wilderness. Oklahoma was lousy with giant spiders.

Keone offered his lopsided grin, spread his hands open, and showed Mike a fuzzy tarantula as big around as a coaster.

“Jesus.”

The kid laughed.

“Get that fucking thing out of here,” Mike said. “Giving me the willies.”

Keone bent to set it outside the barn door.

“No, no, no.” Mike pointed out the door. “Out there. Far away. I don’t want to see it.”

Keone took it away.

Mike would have smashed the spider flat with a shovel except he’d been told they kept the scorpion population down. And while he despised the spiders, at least he’d never woken up in the morning to find one scuttling across his kitchen floor. He couldn’t say the same about the scorpions.

When Keone returned, Mike waved him over to one of the wine vats. “Come on, might as well do this now.” He took a clean wineglass off the shelf, blew into it to clear any dust. He thumbed the tap, filled the glass halfway with red wine, and handed the glass to the kid.

Keone sniffed it. Then he took a swig, swirled it in his mouth. He frowned and swallowed. “Yuck.”

“Hell.” Mike took out a notepad and pencil. “What’s wrong with it?”

“Acid.”

Mike wrote acidic. “A lot or a little?”

“A lot.”

Shit. He wondered if it was too late to add oak chips to cover up.

He took the glass away from Keone. When the wine was closer to being ready, Mike would have to taste it himself. But really, he couldn’t tell the difference. The kid was a better judge.

“Tell you what,” Mike said. “Clean out those carboys, and we’ll call it a day.”

“Right, boss.”

The phone rang.

It was only last year, after Mike began missing calls from distributors, that he’d strung a phone line down to the barn. He grabbed the phone on the fifth ring. “Scorpion Hill Vineyard. What? No, I think you have the wrong number.” A long pause. “Oh.” Another long silence. “Yeah. It’s me. You caught me by surprise. It’s been so long I—” He glanced at Keone. The kid rinsed out a carboy, but Mike could tell he was listening with one ear. “Listen, I need to call you back. Give me your number.” He scribbled it into his notebook. “Wait for me.” He hung up.

He stood there a moment, staring at the phone.

Keone said, “Boss, you okay?”

“Huh?”

“Bad news?”

“No. Just—” Mike shook his head, plopped into the chair behind his desk. He stared blankly at the rough desktop. He looked up, saw that Keone was still watching him.

“Go home, kid.”

“I didn’t finish the carboys.”

“Forget it. Finish tomorrow.”

Keone watched Mike a few more moments before leaving.

Mike stood in the barn’s open doorway and surveyed his property. It suddenly seemed like a strange place, like it had nothing to do with who he was or where he’d come from. He took off his hat, wiped sweat off his forehead.

It was so goddamn hot.

Anthony Minelli, his cousin Vincent, and their pal Andrew Foley played five-card draw on a makeshift table in a nearly empty warehouse on the New York docks.

“Full house, motherfuckers. Queens over sevens.” Vincent drained the rest of his Bud Light, crumpled the can in his fat fist, and tossed it twenty feet. It clanked across the cement floor, echoed off metal walls. Vincent scooped the winnings toward his ample belly. Three dollars and nine cents.

“Nice pot,” Anthony said. “You can buy a fucking Happy Meal. Now shut up and deal.”

“Hey, it’s the skill that counts. I could be on that celebrity poker show on A&E,” Vincent said.

“Fuck you. It’s on Bravo. And you ain’t no celebrity.”

Andrew Foley smiled, reached into the Igloo cooler for one of the few remaining beers. He enjoyed the playful back and forth between the cousins but never joined in. He popped open the beer, sipped. He’d had a few already and was pretty buzzed. He’d also lost nine bucks at poker, not having won a single hand. But that was okay. Like the Minelli cousins, Andrew had been paid a cool grand for his work at the docks today. The money had come just in time.

Andrew was in his junior year at the Manhattan School of Music and he was always short on money. He was a week late on rent when Anthony had called with the offer. Andrew was well aware Anthony and Vincent were wiseguys in training and that a deal with them was sure to be a little shady. Andrew had known the two cousins since they were all in grade school. Andrew’s father and their fathers were pals. He balked at the thought of doing something illegal and maybe getting caught, but Vincent continued to assure him that the whole thing was easy money, a big fat moist piece of cake. Andrew needed cash. Period. Andrew’s landlord wasn’t a forgiving man.

Besides, it really did seem like a pretty easy job. A no-brainer really. Somebody (Just never you mind who. Don’t ask no fucking questions.) wanted a cargo container from one of the big freighter ships unloaded without going through the usual customs. This was a tall order, and a lot of people had to be bribed or distracted. Andrew, Vincent, and Anthony had a simple job. Shepherd the cargo container from the freighter to the unused warehouse way hell and gone down the other end of the wharf. The guy who’d set up the deal didn’t trust the usual union grunts to handle it, and anyway a lone cargo container getting that kind of attention would cause talk. Andrew was being overpaid enough to keep his trap shut. It was understood silence was part of the deal.

They’d forklifted the container into the warehouse and that was that. The job had seemed so simple and the guys were so giddy about their easy payday that Andrew forgot all about an overdue term paper when Anthony produced a cooler of beer and Vincent had pulled a deck of cards out of his pocket.

“What do you think is in there?” Vincent’s eyes shifted momentarily from his cards to the cargo container.

Anthony picked something out of his teeth, then said, “Drugs.”

Vincent raised an eyebrow. “Oh, yeah? You got some inside information?”

Anthony said, “It’s always drugs. Gimme two cards.”

They played cards, talked quietly, drank beer.

The little explosion rattled the warehouse. They dropped their cards and hit the floor. Andrew covered his head with his arms, his heart thumping like a rabbit’s. One of the metal doors on the cargo container creaked open. A chemical smell from the explosive hung in the air.

“Jesus H. Christ.” Anthony was the first to his feet. “What happened?”

Vincent stood up too, dusted himself off. “How the hell am I supposed to know?”

Andrew stayed on the floor, but he uncovered his head and risked a peek. Smoke in the air. Then they heard something, noise from within the container.

“Somebody’s in there,” Andrew whispered.

Vincent shook his head. “That’s fucking impossible.” He’d whispered too.

The cousins were huddled together. Andrew stood up and huddled with them. They watched the cargo container expectantly. It was like a scene in War of the Worlds, Andrew thought. The guys looking at the spaceship, waiting for the aliens to come out. They whispered at each other from the sides of their mouths.

“How could anyone breathe in there?”

“Maybe there’s more than one.”

“Illegal immigrants?”

“Should we go over there?”

“Fuck that. You go over there.”

A figure emerged from the container, and they froze.

The newcomer had dark olive skin, deep brown eyes. Black hair slicked back and dirty. A thick curly beard. He wore a stained denim shirt, threadbare tan pants. Military boots. A small pistol tucked into his waistband. Over his shoulder he carried a large brown duffel bag.

Vincent took a step forward, raised a hand. “Hey!”

Andrew put his hand on Vincent’s shoulder, held him back. What did the dumb wop think he was doing?

The stowaway jumped at the voice, then fixed Vincent with those hard dark eyes. He put his hand on the pistol in his pants, didn’t say a word. Vincent held up his hands in a “no problem here” gesture. The stowaway backed toward the door, his hand on the gun the whole time. He turned, opened the door, and exited the warehouse quickly and without a backward glance.

Anthony recovered first. “What the fuck?”

Andrew let go of Vincent’s shoulder. “What did you think you were going to do?”

Vincent looked a little pale. “Shit if I know. I just saw the guy and . . . Shouldn’t we do something?”

Andrew walked toward the container. “Let’s have a look.” The cousins followed.

The three of them stood at the door and peered inside. Dark. An odd tangle of straps and harnesses. It looked like a car seat had been arranged to withstand rough seas.

Andrew examined the container door, which had been latched from the outside. There was a small hole at the level of the latch blown outward from within, leaving the metal jagged and scorched. The guy inside had known exactly what to do to free himself.

Vincent held his nose. “What a fucking stink.”

Andrew nudged him, pointed into the corner of the container at an object that could only be a makeshift toilet. Food wrappers and other debris littered the container’s floor.

Anthony shook his head. “Oh man. We just helped smuggle some kind of Arab terrorist motherfucker. What are we going to do?”

“Not a goddamn thing,” Vincent said. “We were paid to bring the container here and keep our fucking mouths shut. We weren’t supposed to hang around and play cards. We were never meant to see this. I don’t care if that was Osama Bin Laden’s right-hand guy. We’re going to keep our fucking traps shut and not do a thing.”

Fear bloomed in Andrew’s gut, but he agreed. Maybe if he kept quiet about this, never told a soul, it would all go away.

• • •

He was known among his fellow terrorists as Jamaal 1-2-3.

He walked from the docks straight inland for five blocks, turned right, walked four blocks, then left for another three blocks. He pretended to examine shoes in a store window but was really watching the street behind him in the reflection.

No one appeared to be following him.

He zigzagged another ten minutes, found a pay phone, dropped his duffel at his feet, and dug a slip of paper out of his shirt pocket. There was a phone number. No name. No identifying markings of any kind. It was a local number, but that meant nothing. The call could be rerouted and transferred to any phone in the world. Jamaal might be calling a barbershop in the Bronx or a noodle hut in Kyoto. He dialed the number.

It rang five times before someone picked up. “Hello?”

“This is Jamaal 1-2-3.”

“One moment.” Shuffling papers. Taps at a keyboard. “What seems to be the problem?” A slight accent. Perhaps Eastern European.

“I was seen.” Jamaal explained what had happened.

“I understand.”

The voice asked Jamaal a few questions. Who were the three men? Jamaal didn’t know. What did they look like? Early twenties. American. Two with dark hair, one with lighter brown hair and pale skin. He described their clothes.

“I wasn’t supposed to be seen. If the authorities learn that—”

“It will be taken care of.”

Jamaal said, “But it’s important that—”

“I said it will be taken care of. You must go about your business. Forget the three men. Proceed as planned. Leave the rest to me.” He hung up.

The conversation’s abrupt end surprised Jamaal. He blinked, shrugged, hung up the phone. He stood there a full minute pondering his situation. His mission depended on his ability to blend into the scenery, where he would slowly go about collecting the materials he needed. And in a month or three or a year, when everything was in place, he would strike at the Great Satan for the glory of Allah. But if the American FBI or CIA knew an Arab had been smuggled into the country, they would scour the city looking for him. The witnesses had to be eliminated and quickly, before they could alert anyone.

All he could do was trust the voice on the phone and get on with his work. He shouldered the duffel and walked casually into the asphalt anonymity of New York City.

The man with the vaguely Eastern European accent had a name, but it didn’t matter what it was. He sat in a small room filled with filing cabinets and computers and fax machines and telephones. It didn’t matter where the room was. His office was the world.

He contemplated the problem of Jamaal 1-2-3.

It didn’t matter one iota to the man if Jamaal’s mission failed or not. What mattered to him was his own reputation and the fact that upset clients could be potentially dangerous. In this business, reputation was everything. He was a kind of broker. He made connections, put people with other people. Filled in gaps. He’d promised Jamaal’s organization a completely covert insertion. Now he had a mess to clean up. It was the bane of his profession that he had to rely occasionally on local people to execute the details of his operation. Now he had to send someone to make things right. Going local again would likely compound the problem. He needed someone good. He needed the best.

He picked up the phone, the special secure line, and dialed the number for the most dangerous woman in the world.

2

At that moment, in the middle of the night, the most dangerous woman in the world clung to the tiled roof of a villa in Tuscany, where she worked to circumvent the alarm system on a large skylight. If she could do that, she’d open the skylight, drop inside, and kill a Colombian named Pablo Ramirez.

For five years she had called herself Nikki Enders. This wasn’t her real name, of course, but she had a British passport and a ream of other paperwork that said she was Nikki Enders, and no one ever disputed her. She had a Swiss bank account that had millions of dollars of Nikki Enders’s money in it. Nikki Enders enjoyed a staggeringly expensive home in London, and another three-story house in the Garden District of New Orleans. She wished she could spend more time there. She also had a dozen passports in safety-deposit boxes scattered around the world and could stop being Nikki Enders at a moment’s notice.

But tonight, in Tuscany, Pablo Ramirez would run afoul of Nikki Enders.

Ramirez meant nothing to Nikki. Alive. Dead he was worth five million dollars. She didn’t know who wanted him dead or why. She didn’t care. This was simply Nikki’s job. She fumbled with a pair of alligator clips, squinted at the wires that connected the alarm system. She hated working in the dark.

The cell phone clipped to her belt vibrated against her hip. She flinched, reached back, and turned it off. She silently cursed herself. She was getting sloppy. First she’d left the night goggles behind in the hotel. Then she’d forgotten to turn off her phone. A distraction at the wrong moment might cost her in blood. She wiped the sweat off her forehead with the sleeve of her black bodysuit. She needed to calm down, get her ducks in a row.

Okay, go over the scouting report again. Ramirez had five men with him. It was a four-bedroom villa, and naturally Ramirez would claim the master suite for himself. That left the five bodyguards scattered about. They could be anywhere, sleeping, getting a snack in the kitchen. Nikki had staked out the villa earlier and saw no sign of the usual bevy of whores who kept the men entertained, so she wouldn’t catch any of them screwing. The dim illumination coming up from the skylight suggested they’d turned in for the night.

She checked her guns. The twin .380s hung from her shoulder holsters. She’d already screwed the silencers into place. There was a collapsible sniper rifle and a .40 caliber Desert Eagle strapped to the BMW motorcycle parked a block down the hill, just in case she needed something more formidable. The motorcycle was concealed under the low branches of a tree, but close enough for her to reach it quickly.

Just as she’d hoped, recalling the scouting report and rechecking her equipment helped her focus. She returned to the alarm system and the alligator clips. She fidgeted, rolled to her left, trying to readjust herself to a more comfortable position.

Floodlights flared to life, poured harsh light onto the villa’s roof. From within, a shrill alarm pulsed.

Goddammit!

There must have been some kind of roof sensor that hadn’t been in the scouting report. What should have been a stealthy execution was now going to be a gunfight. It couldn’t be helped, and she didn’t have time to hesitate.

She stood, jumped, brought her feet down hard on the skylight. The glass shattered as she fell through, the shards raining. She landed and rolled, the glass still falling, a glittering shower. She leapt up, drew the silenced automatics.

Two of the Colombians were already coming at her from one of the bedrooms. Their hair was disheveled. Boxer shorts. Sleepy eyes. But they each gripped a little Mac-10. Standard goon armament. Not original but very deadly.

The machine pistols spat fire, rattled nine-millimeter slugs six inches over Nikki’s head. The bullets shredded plaster, knocked a painting off the wall, and obliterated a lamp.

Nikki went flat, rolled along the floor, pistols stretched over her head. She squeezed the triggers, and the silencers dulled the shots to a breathy phoot. She shattered anklebone, and both men yelled and fell. When they were on the floor, she shot each of them in the top of the head.

She leapt to her feet and spun just in time to meet two bodyguards storming her from the other direction. Automatic pistols barked at her. The room filled with streaking lead.

Nikki bolted left, ducking under the fire, turn- ing to the side to make herself a small target. She jumped, fired as she flew through the air, emptying both pistols with a rapid-fire series of phoots, and landed behind an overstuffed couch. She ejected the spent magazines, slapped in new ones. She hunched low against the back of the couch as a fresh flurry of gunfire flayed the cushions. The air filled with downy couch stuffing, like a souvenir snow globe gone horribly wrong. Bullets tore through the couch an inch from Nikki’s face. Not much of a hiding place.

Nikki took a miniature flash grenade from one of her belt pouches. About the size of a golf ball. She thumbed the arming mechanism and tossed it over her shoulder. She waited for the telltale whumpf and shut her eyes against the hot stab of light. She immediately rose from behind the couch. She had to strike before the effect of the grenade faded. One of the goons had dropped his automatic, rubbed his eyes with the heels of his hands. The other had his arm over his eyes, but still waved his pistol, jerking the trigger wildly.

Nikki took him down first. Two quick shots in the chest. She spun on the other one, took three quick steps forward, and leveled her automatic a foot from his forehead. She pulled the trigger. He went stiff, flinched once, and dropped.

The room fell quiet again, the downy furniture stuffing still drifting on the air. A spent shell casing rolled along the hardwood floor.

Then the high rev of a powerful engine, the squeal of tires.

Nikki ran to the window, swept aside the curtains. A red Audi convertible erupted from the garage below her, sped toward the curving road that led down the hill, Ramirez at the wheel.

Son of a bitch!

The villa’s blueprints had been part of the scouting report. Nikki recalled the layout. The door in the kitchen, a narrow staircase that spiraled down to the garage. She ran, found the kitchen and the door. There was only the single road leading down the hill, and it was an obstacle course of switchbacks and hairpin turns. Nikki would likely be able to sprint through the neighboring yards to the motorcycle. Shouldn’t be any problem to catch up to Ramirez.

At the bottom of the staircase she burst into the garage and barely saw the tire iron coming toward her face. She brought up an arm but only partially blocked the blow, the tire iron cracking her wrist and glancing along her forehead. She stumbled back.

The goon came at her with another wild swing. She ducked underneath, kicked his kneecap, heard the fleshy pop. He screamed and went down. She finished him with a punch across the jaw. Nikki didn’t wait to see his eyes roll back. She ran from the garage, flashed across the neighbor’s lawn, and leapt aboard the BMW. She cranked it, accelerated at rocket speed down the hill without turning on the bike’s headlight.

Her wrist flared pain. Perhaps the bone was only bruised. It didn’t seem broken, but it hurt like hell. She’d been careless yet again, forgotten about the fifth bodyguard. Why couldn’t she stay focused? Maybe she was about to start her period. If a man had suggested that, she’d have broken his neck.

Nikki leaned the bike low, took a tight turn fast, and the Audi’s taillights swung into view. She thought about shooting his tires out but didn’t trust herself to handle a pistol and keep the bike steady at the same time. Not on this road at this speed. And not with an injured wrist.

With her headlight off, she didn’t think Ramirez had spotted her. On the next short straightaway, she opened the bike up full throttle, sped toward the Audi until the bike touched the rear bumper.

She leapt up on the seat, hands still tight on the handlebars as she found her balance. She launched herself and kicked the motorcycle away in the same motion. For a terrifying split second, the road flew past beneath her. Nikki landed in the back of the convertible, the motorcycle clattering and crunching along the hardpack in the Audi’s wake.

Ramirez shouted surprise, almost lost control of the Audi, tires squealing on the next turn. She wrapped one arm around his throat, her other hand going to the knife on her belt.

“Puta!” Ramirez grabbed her bad wrist, yanked her arm away from his throat.

Nikki winced, the pain lancing from her wrist up the rest of her arm. She tried to jerk away from Ramirez, but he was too strong. They careened down the road, Ramirez driving with one hand, fighting off Nikki with the other. She punched him in the back of the head. Ramirez shoved her just as he steered the Audi into a sharp turn. She tumbled out of the car, tucked into a ball, landed hard but rolled out of it. She stood, watched the taillights vanish down the road.

Godammit.

She spun, ran back up the road toward her discarded motorcycle. Nikki Enders was in top physical condition and could maintain a sprint uphill without effort. As she ran, she pictured the road, looping and snaking down the mountain. If she hurried, she’d have one more chance at Ramirez.

She arrived at the fallen bike. It was scratched and dented, a rearview mirror ripped off. She bent and pulled the sniper rifle from its sheath—almost without breaking stride. She left the road, ran up the steep hill as she unfolded the stock, and snapped the high-powered scope into place. At the top, she threw herself down in the tall grass, cocked the rifle. She looked through the scope at the road below.

She panted heavily. She forced her heart rate down. She’d need a steady hand for the shot—three hundred fifty, maybe four hundred yards. Her wrist throbbed. She ignored it.

The Audi’s headlights came around the bend. It was too dark to see Ramirez, but she aimed above the driver’s side headlight, estimated a spot on the windshield. She squeezed the trigger. The shot echoed in the night.

The Audi swerved, went off the road at high speed, and slammed into a tree. The smack and crunch of metal. She climbed down the hill to check the kill. Ramirez leaned against the steering wheel, half his head missing. Blood and brain and gunk were splattered across the backseat.

She left the Audi, continued down the hill. Neither the BMW nor any of the other equipment she left behind could be traced to her. She unclipped the cell phone from her belt and checked her recent calls to see who’d phoned. It had been him. The nameless voice on the other end of the phone who arranged all of her contracts. She hated this man—irrationally, yes, but hated him nonetheless. That she should owe her success to a faceless ghost irritated her in a way she couldn’t quite explain. Nikki Enders didn’t like having such an important aspect of her life out of her control.

She dialed his number.

“Hello.” That slight accent. Czech?

“You called?”

“Are you still on the job?” he asked.

“I just finished.”

“Good. I have something else for you.”

Nikki flexed her injured wrist. “I need some downtime.”

“I’d consider it a personal favor,” he said.

Burn in hell. “Fine. But the details need to wait. In the morning. That soon enough?”

“I’ll be waiting for your call.” He hung up.

Nikki Enders shut off her cell phone, sighed, and began the long walk back to a bland rental car safely parked in the small village at the base of the hill. Then she would drive to a prearranged safe house thirty miles away and try to sleep.

3

Mike Foley chopped wood under the blistering Oklahoma sky. Summer. Hot. The thok of the axe biting into the logs echoed off the low hills within the shallow valley. His sun-freckled skin glistened with sweat, his salt-and-pepper chest hair patchy and matted. Working his twenty acres kept him fit, but Mike was old, and tonight he’d pay for the axe work with a sore back and a handful of over-the-counter pain pills. There was too much white in his hair now. Too many lines around his eyes and mouth. His nose looked like a little apple.

It was 101 degrees outside and Mike chopped firewood and he didn’t know why. There was already enough wood stacked behind the cabin to last a hundred years, and maybe Mike just wanted to prove he could still swing the axe. Later he’d walk the row of grapevines looking for more signs that animals were at the leaves again. Deer and rabbit.

He stacked the wood, put on a short-sleeve denim shirt. The sweat had soaked dark patches at the armpits and around the neck. He grabbed his straw hat, clamped it down over his head. He went to look for Keone, the Creek Indian kid who helped him during the summer. Twelve-year-old smart-ass, but a good kid.

“Keone!”

Down one of the vine rows, the kid stuck his head out. “Boss?”

“Wait until I get on the other side, then hit the water.”

Keone flicked him a two-finger salute. The kid was thin, skin a healthy red-brown in the sun, black hair, sharp cheekbones and nose. Dark eyes but big and alert.

Mike walked down one of the long vine rows. A wooden stake hammered into the ground every thirty feet, two metal lines pulled tight between the stakes, so the vines would have something to cling to. He’d rigged up thin PVC pipe along the rows, little pinholes to let the water spray out. On the other side of the vine rows was the small barn that had come with the property, a sun-bleached wooden structure with flecks of dark green paint flaking off. Mike had poured the concrete floor himself and turned the hay barn into his winery, the big press, which he’d also built himself, and the collection of glass carboys and the hand-bottling machine and a few big vats. A little desk in the corner where he kept his books.

He was two feet from the end of the row when the PVC sputtered to life and sprayed him with water. He yelled surprise, ran ten feet, turned around, and scowled.

“Very funny, asshole.”

Keone’s high-pitched laugh floated across the wide field.

Mike threw the big barn doors open to let in air and light. He sat at the battered little desk, took one of his books from the bottom drawer. He’d bought the book on Amazon.com seven years ago. From Bunch to Bottle by Adam Openheimer was basically the complete moron’s guide to growing grapes, fermenting, and bottling. The book had saved his ass on several occasions.

When Mike had originally settled on the remote twenty acres, his intention had only been to hide from the world. In an effort to live quietly and occupy himself, he investigated what he might do with the land, rocky dry soil surrounded by gnarled oaks. Of the twenty acres, nine were on a gentle, open slope. The rest of the property consisted of thick woods or steep, rocky hillside. The soil was too piss-poor for beans or tomatoes or anything else Mike could think of growing.

So for ten years he’d hidden and sulked and watched the seasons go by, all the time living with himself and sinking into a sort of dark, hermitlike existence. And for ten years he hadn’t had a good night’s sleep, the past always there in his dreams, reminding him he couldn’t really run away from what he’d done or who he was.

An article in the Tulsa World had saved him.

A feature detailing the fledgling Oklahoma wine industry. The article led him to Oklahoma State University’s Department of Agriculture Web site, which listed the varieties of hearty grape most likely to thrive in the Okie soil and climate. The loose, rocky ground, hostile for so many different plants and vegetables, was actually good for grapes. And Mike was willing and desperate for anything to take up his time and occupy his mind.

Typically, it took three years for a vine to reach maturity and bear fruit.

I’d better get my ass in gear, Mike had thought.

And he’d purchased the stakes and the wire and a sledgehammer. He broke his back with labor and sweat that first summer, the July sun scorching him pink, then a darker red, the rocks fighting him every inch. The hobby snowballed into an obsession, and he found himself rolling out of his single bed at dawn, coffee mug in one hand, wire spool in the other. He didn’t quit until sundown. It took a month to put up ten rows. He ordered the vines from a nursery in Upstate New York and killed them because he hadn’t soaked them properly before planting. He ordered more, started over.

He found himself in a war and took it seriously. Oklahoma baked the vines in the dry summer. Winter flayed the land with ice. And slowly, over the days, he forgot to think, forgot to dwell on the past or even to look very far ahead. There were only the sun and water and weeds to pull and leaves to check and vines to prune.

He considered it work. He didn’t think of himself as one with Mother Earth or any kind of other hippie bullshit. It was long, hard work and that was all. And he wanted to do it right. He slept, so bone-weary, hands raw, dirt under his fingernails. He slept and slept and never dreamed.

The first crop of grapes had been feeble. The next crop a little better, enough for a hundred bottles of wine, which he corked and stored for a year, then poured out after tasting a glass and nearly throw- ing up.

It got better. Slowly, he learned.

Three years ago, he’d sold five hundred bottles of his first batch of drinkable wine. He called it Scorpion Hill Red. A very plain table wine, not too dry. Local stores in Oklahoma and Kansas and a few in north Texas had agreed to stock it on a regular basis. Store owners told him customers liked the label, a simple black silhouette of a scorpion against a parchment-colored background. Simple yet cheeky.

With some luck, Mike would ship ten thousand bottles next year.

He craned his neck, tried to spot Keone through the barn door. Sometimes he felt he really had to keep an eye on the kid. Once, Keone had lost control of the little tractor and flattened an entire row of ripe grapes. In a fury, he’d chased the kid with a thick switch, but Keone was too fast. It was a week before he’d shown his face at the vineyard again.

Mike couldn’t see the kid, but didn’t hear anything being demolished, so he turned his attention back to the book. He’d read it cover to cover ten times, knew what it would say, but always consulted it anyway. Always go by the book. Mike was a stickler. Follow the steps.

The book told him to spread deodorant soap shavings among the vines. The “smell of people” would keep the animals away. He was ready. He slid open the top desk drawer, took out two bars of Dial and a penknife. Later, he’d walk the perimeter. Right now, he just wanted a drink.

He went to the secondhand refrigerator in the corner of the barn, opened it, perused the beer selection. He had a few different brands. He liked beer.

Mike Foley absolutely hated the taste of wine.

On a hot day like this he’d need something light, a dark or even an amber would make him sluggish. He grabbed a Coors Light, popped the top, slurped. What was the old joke about canoes and Coors Light? Fucking close to water.

He’d just finished the first beer and thought about opening another, when Keone walked into the barn. He had something cupped in his hands.

“Freeze,” Mike shouted.

Keone froze.

“What are you bringing in here? It’s another goddamn spider, isn’t it?” One thing Mike had learned his first month in the wilderness. Oklahoma was lousy with giant spiders.

Keone offered his lopsided grin, spread his hands open, and showed Mike a fuzzy tarantula as big around as a coaster.

“Jesus.”

The kid laughed.

“Get that fucking thing out of here,” Mike said. “Giving me the willies.”

Keone bent to set it outside the barn door.

“No, no, no.” Mike pointed out the door. “Out there. Far away. I don’t want to see it.”

Keone took it away.

Mike would have smashed the spider flat with a shovel except he’d been told they kept the scorpion population down. And while he despised the spiders, at least he’d never woken up in the morning to find one scuttling across his kitchen floor. He couldn’t say the same about the scorpions.

When Keone returned, Mike waved him over to one of the wine vats. “Come on, might as well do this now.” He took a clean wineglass off the shelf, blew into it to clear any dust. He thumbed the tap, filled the glass halfway with red wine, and handed the glass to the kid.

Keone sniffed it. Then he took a swig, swirled it in his mouth. He frowned and swallowed. “Yuck.”

“Hell.” Mike took out a notepad and pencil. “What’s wrong with it?”

“Acid.”

Mike wrote acidic. “A lot or a little?”

“A lot.”

Shit. He wondered if it was too late to add oak chips to cover up.

He took the glass away from Keone. When the wine was closer to being ready, Mike would have to taste it himself. But really, he couldn’t tell the difference. The kid was a better judge.

“Tell you what,” Mike said. “Clean out those carboys, and we’ll call it a day.”

“Right, boss.”

The phone rang.

It was only last year, after Mike began missing calls from distributors, that he’d strung a phone line down to the barn. He grabbed the phone on the fifth ring. “Scorpion Hill Vineyard. What? No, I think you have the wrong number.” A long pause. “Oh.” Another long silence. “Yeah. It’s me. You caught me by surprise. It’s been so long I—” He glanced at Keone. The kid rinsed out a carboy, but Mike could tell he was listening with one ear. “Listen, I need to call you back. Give me your number.” He scribbled it into his notebook. “Wait for me.” He hung up.

He stood there a moment, staring at the phone.

Keone said, “Boss, you okay?”

“Huh?”

“Bad news?”

“No. Just—” Mike shook his head, plopped into the chair behind his desk. He stared blankly at the rough desktop. He looked up, saw that Keone was still watching him.

“Go home, kid.”

“I didn’t finish the carboys.”

“Forget it. Finish tomorrow.”

Keone watched Mike a few more moments before leaving.

Mike stood in the barn’s open doorway and surveyed his property. It suddenly seemed like a strange place, like it had nothing to do with who he was or where he’d come from. He took off his hat, wiped sweat off his forehead.

It was so goddamn hot.

Descriere

A retired hitman gets back into the game to help out a nephew, but soon finds himself up against a hot young female assassin and a whole new set of rules in this new work by the Edgar Award-nominated author of "Gun Monkeys." Original.

Premii

- Anthony Awards Nominee, 2007