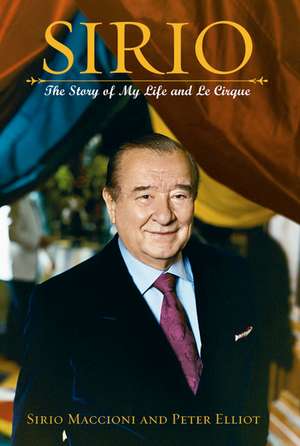

Sirio: The Story of My Life and Le Cirque

Autor Peter J. Elliot, Sirio Maccionien Limba Engleză Hardback – 3 iun 2004

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

IACP Crystal Whisk Award (2005)

By 1961, the dashing young Maccioni had become maitre d' at New York's most storied restaurant, the Colony. Within thirteen years, he had the experience and contacts he needed to launch his own restaurant, Le Cirque, which quickly became the hub of cafe society in New York.

From hiring the right chefs and revolutionizing the way top restaurants operate to popularizing now-famous dishes such as pasta primavera and creme brulee, Maccioni reveals how he made Le Cirque such a long-running success - a success that reached new heights when the restaurant moved to a new location in 1997. Along the way, Maccioni explains how he's dealt with defecting chefs and demanding customers. And through it all, he pays tribute to his proud Tuscan roots and to his wife and their three sons, who operate the family's other New York restaurant, Osteria del Circo, as well as restaurants in Las Vegas and Mexico City.

Like Maccioni himself, Sirio is full of passion, energy, and life - the unforgettable story of the world's most extraordinary restaurateur.

Preț: 222.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 333

Preț estimativ în valută:

42.53€ • 44.52$ • 35.19£

42.53€ • 44.52$ • 35.19£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780471204565

ISBN-10: 0471204560

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.69 kg

Editura: HarperCollins Publishers

Colecția Harvest

Locul publicării:Hoboken, United States

ISBN-10: 0471204560

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.69 kg

Editura: HarperCollins Publishers

Colecția Harvest

Locul publicării:Hoboken, United States

Public țintă

Readers interested in food–related memoirs and biographies of well–known food figures such as Jacques Pepin and Julia Child.Recenzii

Sirio Maccioni has lived his life on the periphery of celebrity photographs. As maitre d' and owner of Le Cirque, the New York restaurant where Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger reconciled, Frank Sinatra parked his limo and the "ladies who lunch" lunched, he has served for three decades as something of a mealtime matador to high society.

His memoir might have been a shallow name-dropper, full of chat about the Kennedy clan and insights into caviar. But that's the last thing "Sirio" is. Indeed, from the first chapter's anecdote of Ronald Reagan tossing off an ethnic joke, the book signals that it's no gladhanding salute to famous people or monied swells. There is barely another mention of a bold-face name for some 60 pages, but the reader won't mind.

This is an immigrant's story. In its opening chapters, it keenly evokes a time and place: Italy during the war. "My father was a very good father," the restaurateur writes. "In those days, there was no bad father." In rural Montecatini, first occupied by Germans and then Americans, the author is desperately poor and loses his mother early to pneumonia. What could be bathetic is instead spare and unflinching: He writes of hating the pity of the villagers and of his impatience, at the age of 10, at their empty assurances that his father will recover after a German mortar attack. ("There was no medicine, and no blood," he writes, dismissing the platitudes.)

With little to eat, Mr. Maccioni knowingly transforms himself into the stock character of war movies: the adorable Italian orphan boy begging for candy from servicemen. "We worked for those chocolates," he notes. He also pays attention as his war-torn city recovers swiftly after the war by marketing itself as a spa for café society. It was a lesson not lost on the young teenager, who was soon making his way in an old-fashioned world of restaurant service, where waiters were timed on how fast they could debone a chicken and the same staff worked breakfast through dinner, taking their breaks in between and sleeping together in a single room.

Pity the poor tourists in Germany who told the young waiter that, if he were ever in Paris, they had a job for him in their restaurant. He showed up with little French and no money and refused to leave, then traded up to the Plaza-Athenée when he was more fluent. He was still a "skinny, stupid spaghetti boy," he writes, desperate not to return to Montecatini until he could look down on all the people who, he says, had looked down on him.

As he moved to different hotels, restaurants and continents, he was careful to let the jet-setting clientele spot him (greeting the Onassis clan, for example, in a variety of venues). By midway through the book, Mr. Maccioni is in New York, having deserted his post on a posh cruise ship. He nabs a waiter's job at the prestigious Colony, gets a promotion and then the maitre d's tales begin.

He tells of the time both agent Swifty Lazar and publisher John Fairchild demanded the same corner table. Mr. Maccioni favored Lazar and was mortified when he found the two were meeting for lunch together. He tells of the pretty women who ate free for decades at Le Cirque, of the politics of sitting Canadian premier Pierre Trudeau nowhere near his wife, and of the betrayal and departure of his best chef, Daniel Boulud.

Mr. Maccioni is at his most interesting when he tackles the delicate issue of class, of being "a servant, but never servile." It is true that, by his own good fortune and entrepreneurial panache, he joined an elite of sorts by starting his own restaurant and making it thrive. But the book seethes with a class tension that will sting true for everyone who has ever worked among the well-to-do. Repeatedly Mr. Maccioni, maestro to the monied, warns of mistaking client friendships for real ones. He came to know Frank Sinatra, for instance, first at the Colony and then at Le Cirque, going around with him after hours to rival restaurants. —

His memoir might have been a shallow name-dropper, full of chat about the Kennedy clan and insights into caviar. But that's the last thing "Sirio" is. Indeed, from the first chapter's anecdote of Ronald Reagan tossing off an ethnic joke, the book signals that it's no gladhanding salute to famous people or monied swells. There is barely another mention of a bold-face name for some 60 pages, but the reader won't mind.

This is an immigrant's story. In its opening chapters, it keenly evokes a time and place: Italy during the war. "My father was a very good father," the restaurateur writes. "In those days, there was no bad father." In rural Montecatini, first occupied by Germans and then Americans, the author is desperately poor and loses his mother early to pneumonia. What could be bathetic is instead spare and unflinching: He writes of hating the pity of the villagers and of his impatience, at the age of 10, at their empty assurances that his father will recover after a German mortar attack. ("There was no medicine, and no blood," he writes, dismissing the platitudes.)

With little to eat, Mr. Maccioni knowingly transforms himself into the stock character of war movies: the adorable Italian orphan boy begging for candy from servicemen. "We worked for those chocolates," he notes. He also pays attention as his war-torn city recovers swiftly after the war by marketing itself as a spa for café society. It was a lesson not lost on the young teenager, who was soon making his way in an old-fashioned world of restaurant service, where waiters were timed on how fast they could debone a chicken and the same staff worked breakfast through dinner, taking their breaks in between and sleeping together in a single room.

Pity the poor tourists in Germany who told the young waiter that, if he were ever in Paris, they had a job for him in their restaurant. He showed up with little French and no money and refused to leave, then traded up to the Plaza-Athenée when he was more fluent. He was still a "skinny, stupid spaghetti boy," he writes, desperate not to return to Montecatini until he could look down on all the people who, he says, had looked down on him.

As he moved to different hotels, restaurants and continents, he was careful to let the jet-setting clientele spot him (greeting the Onassis clan, for example, in a variety of venues). By midway through the book, Mr. Maccioni is in New York, having deserted his post on a posh cruise ship. He nabs a waiter's job at the prestigious Colony, gets a promotion and then the maitre d's tales begin.

He tells of the time both agent Swifty Lazar and publisher John Fairchild demanded the same corner table. Mr. Maccioni favored Lazar and was mortified when he found the two were meeting for lunch together. He tells of the pretty women who ate free for decades at Le Cirque, of the politics of sitting Canadian premier Pierre Trudeau nowhere near his wife, and of the betrayal and departure of his best chef, Daniel Boulud.

Mr. Maccioni is at his most interesting when he tackles the delicate issue of class, of being "a servant, but never servile." It is true that, by his own good fortune and entrepreneurial panache, he joined an elite of sorts by starting his own restaurant and making it thrive. But the book seethes with a class tension that will sting true for everyone who has ever worked among the well-to-do. Repeatedly Mr. Maccioni, maestro to the monied, warns of mistaking client friendships for real ones. He came to know Frank Sinatra, for instance, first at the Colony and then at Le Cirque, going around with him after hours to rival restaurants. —

Notă biografică

PETER ELLIOT is the food critic for Bloomberg LP and host of Dine

Premii

- IACP Crystal Whisk Award Nominee, 2005