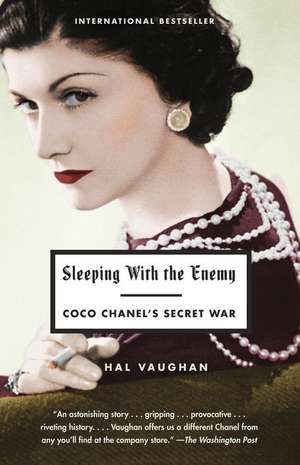

Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel's Secret War

Autor Hal Vaughanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 aug 2012

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was the high priestess of couture who created the look of the modern woman. By the 1920s she had amassed a fortune and went on to create an empire. But her life from 1941 to 1954 has long been shrouded in rumor and mystery, never clarified by Chanel or her many biographers. Hal Vaughan exposes the truth of her wartime collaboration and her long affair with the playboy Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage—who ran a spy ring and reported directly to Goebbels. Vaughan pieces together how Chanel became a Nazi agent, how she escaped arrest after the war and joined her lover in exile in Switzerland, and how—despite suspicions about her past—she was able to return to Paris at age seventy and rebuild the iconic House of Chanel.

Preț: 104.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.01€ • 20.96$ • 16.59£

20.01€ • 20.96$ • 16.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 18 martie-01 aprilie

Livrare express 04-08 martie pentru 27.58 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307475916

ISBN-10: 0307475913

Pagini: 313

Ilustrații: 74 ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307475913

Pagini: 313

Ilustrații: 74 ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Hal Vaughan has been a newsman, foreign correspondent, and documentary film producer working in Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia since 1957. He served in the U.S. military in World War II and Korea and has held various posts as a U.S. Foreign Service officer. Vaughan is the author of Doctor to the Resistance: The Heroic True Story of an American Surgeon and His Family in Occupied Paris and FDR’s 12 Apostles: The Spies Who Paved the Way for the Invasion of North Africa. He lives in Paris.

Extras

PROLOGUE

Despite her age she sparkles; she is the only volcano in the Auvergne that is not extinct . . . the most brilliant, the most impetuous, the most brilliantly insufferable woman that ever was.

Gabrielle Chanel had barely been laid to rest in her designer sepulcher at Lausanne, Switzerland, when the city of Paris announced that France’s first lady and Chanel’s admirer and client, the wife of French president Georges Pompidou, would open an official exhibit celebrating Chanel’s life and work in Paris in October 1972. Shortly before, Hebe Dorsey, the legendary fashion editor of the International Herald Tribune, reported the “homage to Chanel” probably would be canceled or, at the very least, postponed. Dorsey revealed that Pierre Galante, an editor at Paris Match, would soon expose shocking documents from French counterintelligence archives. Dorsey alleged that Chanel had had an affair during the German occupation of Paris with Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage: “a dangerous agent of the German information service—likely an agent of the Gestapo.”

Chanel, the epitome of French good taste, in bed with a Nazi spy—worse yet, involved with an agent of the hated Gestapo? To the French, and especially to French Jews, veterans of the Resistance, and survivors of SS- run concentration camps, German collaborators were pariahs or, worse, fit to be spat upon. Granted, for years fashionable Paris had gossiped that Chanel had shacked up during the occupation with a German lover called Spatz—German for sparrow— at the chic Hôtel Ritz where Nazi bigwigs like Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels were pampered by the Swiss management. But the Gestapo? Hadn’t Chanel dressed Mme Pompidou? Hadn’t she been honored at the Élysée Palace? How could such an icon of French society have bedded a “German spy”? It was hard to believe. Even though tens of thousands of French men and women collabos had escaped punishment, being a willing bedmate and helpmate of a German offi cer still reeked of treason in 1972. Their liaison would last over ten years, leading one observer to wonder if Chanel “cared about political ideology but wanted instead to be loved and to hell with politics.”

The timing for the proposed national celebration of Chanel’s life and work could hardly have been worse. On top of everything else, the U.S. publisher Alfred A. Knopf had just released Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940ߝ1944 by American historian Robert O. Paxton. This study of the Vichy regime under Marshal Philippe Pétain left many French scholars chagrined and upstaged on their own academic home turf. Based on material from German archives— because the French government had forbidden access to the Vichy archives— Paxton’s book proved that Pétain’s collaboration with this particular cohort of full- blooded Nazis had been voluntary rather than forced on Vichy.

For the Pompidou political machine facing an election in just twenty-four months and for the Chanel organization confronting allegations that its founder had been linked to the Gestapo, postponement of the “homage to Chanel” was the only option. There was also solid and damning evidence of her collaboration in an upcoming biography by Pierre Galante— scheduled for publication in Paris and New York. A former resistance fighter and husband of English actress Olivia de Havilland, Galante claimed his information was based on access to French counterintelligence sources.

Le Tout-Paris was talking about the book before it was even published. Edmonde Charles-Roux, a Goncourt Prizeߝwinning novelist, was outraged by Galante’s revelations. She labeled his claims nonsense: [Dincklage] “was not in the Gestapo.” Spatz and Chanel, she maintained, just enjoyed an amorous friendship. (Madame Charles- Roux was also writing a Chanel biography and presumably did not have access to Galante’s sources.)

Marcel Haedrich, an earlier Chanel biographer, claimed that Spatz was merely a bon vivant who “loved eating, wines, cigars, and beautiful clothes . . . thanks to Chanel he had an easy life . . . he waited for her in her salon . . . he would kiss Chanel’s hand and murmur: “ ‘how are you this morning?’ ”—and because the two spoke English together she would say, “He is not German, his mother was English.”

Asked by Women’s Wear Daily, the New York garment industry paper, in September 1972: “[W]as Chanel, Paris’s greatest couturière, really an agent for the Gestapo?” Charles-Roux replied, “[Dincklage] was not in the Gestapo. He was attached to a commission here [in Paris] and he did give information. He had a dirty job. But we must remember, it was war and he had the misfortune to be a German.” Years later, Charles- Roux learned that she had been duped— manipulated by Chanel and her lawyer, René de Chambrun.

The liberation of Paris in August 1944 began with bloody street fighting, pitting German troopers against a scruffy, ragtag band of General Charles de Gaulle’s irregular street fighters called Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (the FFI), which Chanel would dub “les Fifis.” They were joined by Communist fighters, Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), and civilian police offi cers. Facing German forces, some resistants were armed only with light police weapons; others had World War Iߝvintage revolvers and rifles; a few had Molotov cocktails and weapons seized from dead Boches. The street fighters were often young students, their sleeves rolled up on bony arms and wearing sandals. Their FFI, FTP, and police armbands served as uniforms.

In the last week of August the U.S.-equipped Free French Army, led by General Leclerc, nom de guerre for Philippe de Hauteclocque, relieved the Paris insurgency, and the German garrison surrendered. After four years of often- brutal occupation, Paris was liberated— free from the threat of arrest, torture, and deportation to concentration camps. Church bells rang, whistles blew; people danced in the streets. Except for some provinces, such as Alsace and Lorraine, France was under General Charles de Gaulle’s Free French.

A thirst for revenge gripped the nation in the last days of August. Four years of shame, pent-up fear, hate, and frustration erupted. Revengeful citizens roamed the streets of French cities and towns. The guilty— and many innocents— were punished as private scores were settled. Many alleged collaborators were beaten; some murdered. “Horizontal collaborators”—women and girls who were known to have slept with Germans— were dragged through the streets. A few would have the swastika branded into their flesh; many would have their heads shaved. Civilian collabos—even some physicians who had treated the Boche—were shot on sight. The lucky were jailed, to be tried later for treason. Finally, General de Gaulle’s soldiers and his provisional magistrates put a stop to this internecine war.

The twentieth-century monstre sacré of fashion, Chanel was among those marked for vengeance. The French called it épuration— a purge, a cleansing of France’s wounds after so many had died and suffered under Nazi rule.

Within days after the last German troopers left Paris, Chanel hurried to give out bottles of Chanel No. 5 to American GIs. Then the Fifi s arrested her. Truculent young men brought her to an FFI headquarters for questioning.

Chanel was released within a few hours, saved by the intervention of Winston Churchill operating through Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to de Gaulle’s French provisional government. A few days later, she fl ed to Lausanne, Switzerland, where she would later be joined by Dincklage—still a handsome man at forty-eight. Chanel was sixty- one years old.

De Gaulle ’s government soon ordered Ministry of Justice magistrates to use special courts to try those suspected of aiding the Nazi regime— a crime under the French criminal code. Among the first to be tried were Vichy chief Philippe Pétain and his prime minister, Pierre Laval. Both were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. De Gaulle spared Pétain because of his old age, but Laval was shot.

During the postwar process of cleansing, French military and civilian courts tried or examined 160,287 cases in all. While 7,037 people were condemned to death, only about 1,500 were actually executed. The rest of the death sentences were commuted to prison sentences.

It took nearly two years after the Liberation before a French Court of Justice issued an “urgent” warrant to bring Chanel before French authorities. On April 16, 1946, Judge Roger Serre ordered police and French border patrols to bring her to Paris for questioning. A month later he ordered a full investigation of her wartime activities. It wasn’t Chanel’s relations with Dincklage that attracted Serre’s attention. Rather, the judge had discovered that Chanel had cooperated with German military intelligence and had been teamed with a French traitor, Baron Louis de Vaufreland. French police had identifi ed the baron as a thief and wartime German agent who was tagged as a “V- Mann” on German Abwehr documents— meaning, in the parlance of the Gestapo and German intelligence agencies, that he was a trusted agent.

Serre, forty-eight years old and with more than twenty years of experience as a magistrate, grilled Vaufreland for months. Serre also learned from French intelligence offi cers how Vaufreland and Chanel had collaborated with the German military. Slowly, Serre, a painstaking investigator, turned up details of Chanel’s Abwehr recruitment, her collaboration with Vaufreland, and how she and the German spy had embarked on an Abwehr mission to Madrid in 1941.

During her interrogation and testimony, Chanel would claim Vaufreland’s stories were “fantasies.” But French police and court documents tell another story: while French Resistance fighters were shooting Germans in the summer of 1941, Chanel was recruited as an agent by the Abwehr. Fifty pages of minute detail describe how Chanel and the trusted Abwehr agent F- 7117— Baron Louis de Vaufreland Piscatory— were recruited and linked together by German agent Lieutenant Hermann Niebuhr, alias Dr. Henri Neubauer, to travel together in the summer of 1941 on an espionage mission for German military intelligence. Vaufreland’s job was to identify men and women who could be recruited, or coerced, into spying for Nazi Germany. Chanel, who knew Sir Samuel Hoare, the British ambassador to Spain, via her relations with the Duke of Westminster, Hugh Grosvenor, was there to provide cover for Vaufreland’s work.

It is doubtful that Judge Serre ever learned the extent and depth of Chanel’s collaboration with Nazi offi cials. It is unlikely he saw the British secret intelligence report documenting what Count Joseph von Ledebur-Wicheln, an Abwehr agent and defector, told MI6 agents in 1944. In the fi le, Ledebur discussed how Chanel and Baron von Dincklage traveled to bombed- out Berlin in 1943 to offer Chanel’s services as an agent to SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Ledebur also revealed that Chanel, after visiting Berlin, undertook a second mission to Madrid for SS general Walter Schellenberg, Himmler’s chief of SS intelligence. Serre would never learn that Dincklage had been a German military intelligence officer since after WWI: Abwehr agent F- 8680.

It is also unlikely that Judge Serre ever discovered the depth of Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis in occupied Paris or that she was a paid agent of Walter Schellenberg. Nor did he know that Dincklage worked for the Abwehr and the Gestapo in France and for the Abwehr in Switzerland and, later, during the occupation of Paris.

Despite her age she sparkles; she is the only volcano in the Auvergne that is not extinct . . . the most brilliant, the most impetuous, the most brilliantly insufferable woman that ever was.

Gabrielle Chanel had barely been laid to rest in her designer sepulcher at Lausanne, Switzerland, when the city of Paris announced that France’s first lady and Chanel’s admirer and client, the wife of French president Georges Pompidou, would open an official exhibit celebrating Chanel’s life and work in Paris in October 1972. Shortly before, Hebe Dorsey, the legendary fashion editor of the International Herald Tribune, reported the “homage to Chanel” probably would be canceled or, at the very least, postponed. Dorsey revealed that Pierre Galante, an editor at Paris Match, would soon expose shocking documents from French counterintelligence archives. Dorsey alleged that Chanel had had an affair during the German occupation of Paris with Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage: “a dangerous agent of the German information service—likely an agent of the Gestapo.”

Chanel, the epitome of French good taste, in bed with a Nazi spy—worse yet, involved with an agent of the hated Gestapo? To the French, and especially to French Jews, veterans of the Resistance, and survivors of SS- run concentration camps, German collaborators were pariahs or, worse, fit to be spat upon. Granted, for years fashionable Paris had gossiped that Chanel had shacked up during the occupation with a German lover called Spatz—German for sparrow— at the chic Hôtel Ritz where Nazi bigwigs like Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels were pampered by the Swiss management. But the Gestapo? Hadn’t Chanel dressed Mme Pompidou? Hadn’t she been honored at the Élysée Palace? How could such an icon of French society have bedded a “German spy”? It was hard to believe. Even though tens of thousands of French men and women collabos had escaped punishment, being a willing bedmate and helpmate of a German offi cer still reeked of treason in 1972. Their liaison would last over ten years, leading one observer to wonder if Chanel “cared about political ideology but wanted instead to be loved and to hell with politics.”

The timing for the proposed national celebration of Chanel’s life and work could hardly have been worse. On top of everything else, the U.S. publisher Alfred A. Knopf had just released Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940ߝ1944 by American historian Robert O. Paxton. This study of the Vichy regime under Marshal Philippe Pétain left many French scholars chagrined and upstaged on their own academic home turf. Based on material from German archives— because the French government had forbidden access to the Vichy archives— Paxton’s book proved that Pétain’s collaboration with this particular cohort of full- blooded Nazis had been voluntary rather than forced on Vichy.

For the Pompidou political machine facing an election in just twenty-four months and for the Chanel organization confronting allegations that its founder had been linked to the Gestapo, postponement of the “homage to Chanel” was the only option. There was also solid and damning evidence of her collaboration in an upcoming biography by Pierre Galante— scheduled for publication in Paris and New York. A former resistance fighter and husband of English actress Olivia de Havilland, Galante claimed his information was based on access to French counterintelligence sources.

Le Tout-Paris was talking about the book before it was even published. Edmonde Charles-Roux, a Goncourt Prizeߝwinning novelist, was outraged by Galante’s revelations. She labeled his claims nonsense: [Dincklage] “was not in the Gestapo.” Spatz and Chanel, she maintained, just enjoyed an amorous friendship. (Madame Charles- Roux was also writing a Chanel biography and presumably did not have access to Galante’s sources.)

Marcel Haedrich, an earlier Chanel biographer, claimed that Spatz was merely a bon vivant who “loved eating, wines, cigars, and beautiful clothes . . . thanks to Chanel he had an easy life . . . he waited for her in her salon . . . he would kiss Chanel’s hand and murmur: “ ‘how are you this morning?’ ”—and because the two spoke English together she would say, “He is not German, his mother was English.”

Asked by Women’s Wear Daily, the New York garment industry paper, in September 1972: “[W]as Chanel, Paris’s greatest couturière, really an agent for the Gestapo?” Charles-Roux replied, “[Dincklage] was not in the Gestapo. He was attached to a commission here [in Paris] and he did give information. He had a dirty job. But we must remember, it was war and he had the misfortune to be a German.” Years later, Charles- Roux learned that she had been duped— manipulated by Chanel and her lawyer, René de Chambrun.

The liberation of Paris in August 1944 began with bloody street fighting, pitting German troopers against a scruffy, ragtag band of General Charles de Gaulle’s irregular street fighters called Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (the FFI), which Chanel would dub “les Fifis.” They were joined by Communist fighters, Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), and civilian police offi cers. Facing German forces, some resistants were armed only with light police weapons; others had World War Iߝvintage revolvers and rifles; a few had Molotov cocktails and weapons seized from dead Boches. The street fighters were often young students, their sleeves rolled up on bony arms and wearing sandals. Their FFI, FTP, and police armbands served as uniforms.

In the last week of August the U.S.-equipped Free French Army, led by General Leclerc, nom de guerre for Philippe de Hauteclocque, relieved the Paris insurgency, and the German garrison surrendered. After four years of often- brutal occupation, Paris was liberated— free from the threat of arrest, torture, and deportation to concentration camps. Church bells rang, whistles blew; people danced in the streets. Except for some provinces, such as Alsace and Lorraine, France was under General Charles de Gaulle’s Free French.

A thirst for revenge gripped the nation in the last days of August. Four years of shame, pent-up fear, hate, and frustration erupted. Revengeful citizens roamed the streets of French cities and towns. The guilty— and many innocents— were punished as private scores were settled. Many alleged collaborators were beaten; some murdered. “Horizontal collaborators”—women and girls who were known to have slept with Germans— were dragged through the streets. A few would have the swastika branded into their flesh; many would have their heads shaved. Civilian collabos—even some physicians who had treated the Boche—were shot on sight. The lucky were jailed, to be tried later for treason. Finally, General de Gaulle’s soldiers and his provisional magistrates put a stop to this internecine war.

The twentieth-century monstre sacré of fashion, Chanel was among those marked for vengeance. The French called it épuration— a purge, a cleansing of France’s wounds after so many had died and suffered under Nazi rule.

Within days after the last German troopers left Paris, Chanel hurried to give out bottles of Chanel No. 5 to American GIs. Then the Fifi s arrested her. Truculent young men brought her to an FFI headquarters for questioning.

Chanel was released within a few hours, saved by the intervention of Winston Churchill operating through Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to de Gaulle’s French provisional government. A few days later, she fl ed to Lausanne, Switzerland, where she would later be joined by Dincklage—still a handsome man at forty-eight. Chanel was sixty- one years old.

De Gaulle ’s government soon ordered Ministry of Justice magistrates to use special courts to try those suspected of aiding the Nazi regime— a crime under the French criminal code. Among the first to be tried were Vichy chief Philippe Pétain and his prime minister, Pierre Laval. Both were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. De Gaulle spared Pétain because of his old age, but Laval was shot.

During the postwar process of cleansing, French military and civilian courts tried or examined 160,287 cases in all. While 7,037 people were condemned to death, only about 1,500 were actually executed. The rest of the death sentences were commuted to prison sentences.

It took nearly two years after the Liberation before a French Court of Justice issued an “urgent” warrant to bring Chanel before French authorities. On April 16, 1946, Judge Roger Serre ordered police and French border patrols to bring her to Paris for questioning. A month later he ordered a full investigation of her wartime activities. It wasn’t Chanel’s relations with Dincklage that attracted Serre’s attention. Rather, the judge had discovered that Chanel had cooperated with German military intelligence and had been teamed with a French traitor, Baron Louis de Vaufreland. French police had identifi ed the baron as a thief and wartime German agent who was tagged as a “V- Mann” on German Abwehr documents— meaning, in the parlance of the Gestapo and German intelligence agencies, that he was a trusted agent.

Serre, forty-eight years old and with more than twenty years of experience as a magistrate, grilled Vaufreland for months. Serre also learned from French intelligence offi cers how Vaufreland and Chanel had collaborated with the German military. Slowly, Serre, a painstaking investigator, turned up details of Chanel’s Abwehr recruitment, her collaboration with Vaufreland, and how she and the German spy had embarked on an Abwehr mission to Madrid in 1941.

During her interrogation and testimony, Chanel would claim Vaufreland’s stories were “fantasies.” But French police and court documents tell another story: while French Resistance fighters were shooting Germans in the summer of 1941, Chanel was recruited as an agent by the Abwehr. Fifty pages of minute detail describe how Chanel and the trusted Abwehr agent F- 7117— Baron Louis de Vaufreland Piscatory— were recruited and linked together by German agent Lieutenant Hermann Niebuhr, alias Dr. Henri Neubauer, to travel together in the summer of 1941 on an espionage mission for German military intelligence. Vaufreland’s job was to identify men and women who could be recruited, or coerced, into spying for Nazi Germany. Chanel, who knew Sir Samuel Hoare, the British ambassador to Spain, via her relations with the Duke of Westminster, Hugh Grosvenor, was there to provide cover for Vaufreland’s work.

It is doubtful that Judge Serre ever learned the extent and depth of Chanel’s collaboration with Nazi offi cials. It is unlikely he saw the British secret intelligence report documenting what Count Joseph von Ledebur-Wicheln, an Abwehr agent and defector, told MI6 agents in 1944. In the fi le, Ledebur discussed how Chanel and Baron von Dincklage traveled to bombed- out Berlin in 1943 to offer Chanel’s services as an agent to SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Ledebur also revealed that Chanel, after visiting Berlin, undertook a second mission to Madrid for SS general Walter Schellenberg, Himmler’s chief of SS intelligence. Serre would never learn that Dincklage had been a German military intelligence officer since after WWI: Abwehr agent F- 8680.

It is also unlikely that Judge Serre ever discovered the depth of Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis in occupied Paris or that she was a paid agent of Walter Schellenberg. Nor did he know that Dincklage worked for the Abwehr and the Gestapo in France and for the Abwehr in Switzerland and, later, during the occupation of Paris.

Recenzii

“[Hal Vaughan] ably demonstrates that Chanel was far from an innocent victim of circumstance during the second world war but a fully fledged Abwehr (German secret service) agent with her own number and codename: Westminster (no doubt a nod to her one-time lover, the Duke of Westminster). . . Vaughan, who writes with welcome economy and flair, deserves a lot of credit for finally unraveling the strands of Chanel’s deeply deceptive personality.”

—Tobias Grey, Financial Times

“[Sleeping with the Enemy] distinguishes itself from the many other Chanel biographies by tackling the dicey subject of Gabrielle Chanel’s activities during World War II . . . This is a frank and unsentimental portrait of a figure that fashion writers are nearly incapable of criticizing. . . While Vaughan’s discussions of Chanel’s contributions to fashion add nothing new to the extensive literature on her, he more than makes up for it with his impressive research and the never-before-seen information that he has unearthed about her wartime activities. . . . What Sleeping with the Enemy offers is a more rounded look at a figure who has been over-studied and under-examined.”

—Isabel Schwab, The New Republic online

“[A] compelling chronicle of Coco Chanel . . . a different Chanel from any you’ll find at the company store . . . by no means the account of an emerging style but a tale of how a single-minded woman faced history, made hard choices, connived, lied, collaborated and used every imaginable wile to survive and see that the people she cared about survived with her . . . Vaughan has gleaned many of the details of Chanel’s collaboration from documents that were scattered for years throughout European archives . . . It’s an astonishing story . . gripping . . . provocative . . . riveting history.”

—Marie Arana, The Washington Post

“Chanel’s war years, as explored by Hal Vaughan, are as camera-ready and as neck-deep in melodrama as Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds,” and just as hard to forget now that they’re exposed.”

—David D’Arcy, San Francisco Chronicle

"Hal Vaughan has done a stupendous job of research . . . Vaughan draws a brilliant portrait . . a terrific and fascinating story. . . wonderfully told, and full of great characters. . . Vaughan brings her to life so vividly that we understand why no less a judge than André Malraux said that "from this century in France only three names will remain: de Gaulle, Picasso, and Chanel.". . . It is that rarest of good reads, a biography about a famous person with a surprise on every page. Nancy Mitford, I think, would have loved it, and written a wonderful letter to Evelyn Waugh about it!"

—Michael Korda, The Daily Beast

—Tobias Grey, Financial Times

“[Sleeping with the Enemy] distinguishes itself from the many other Chanel biographies by tackling the dicey subject of Gabrielle Chanel’s activities during World War II . . . This is a frank and unsentimental portrait of a figure that fashion writers are nearly incapable of criticizing. . . While Vaughan’s discussions of Chanel’s contributions to fashion add nothing new to the extensive literature on her, he more than makes up for it with his impressive research and the never-before-seen information that he has unearthed about her wartime activities. . . . What Sleeping with the Enemy offers is a more rounded look at a figure who has been over-studied and under-examined.”

—Isabel Schwab, The New Republic online

“[A] compelling chronicle of Coco Chanel . . . a different Chanel from any you’ll find at the company store . . . by no means the account of an emerging style but a tale of how a single-minded woman faced history, made hard choices, connived, lied, collaborated and used every imaginable wile to survive and see that the people she cared about survived with her . . . Vaughan has gleaned many of the details of Chanel’s collaboration from documents that were scattered for years throughout European archives . . . It’s an astonishing story . . gripping . . . provocative . . . riveting history.”

—Marie Arana, The Washington Post

“Chanel’s war years, as explored by Hal Vaughan, are as camera-ready and as neck-deep in melodrama as Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds,” and just as hard to forget now that they’re exposed.”

—David D’Arcy, San Francisco Chronicle

"Hal Vaughan has done a stupendous job of research . . . Vaughan draws a brilliant portrait . . a terrific and fascinating story. . . wonderfully told, and full of great characters. . . Vaughan brings her to life so vividly that we understand why no less a judge than André Malraux said that "from this century in France only three names will remain: de Gaulle, Picasso, and Chanel.". . . It is that rarest of good reads, a biography about a famous person with a surprise on every page. Nancy Mitford, I think, would have loved it, and written a wonderful letter to Evelyn Waugh about it!"

—Michael Korda, The Daily Beast