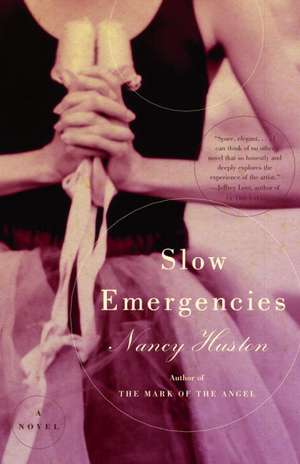

Slow Emergencies

Autor Nancy Hustonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2001

Slow Emergencies conveys an irresistible impulse to create, and illustrates the emotional turmoil that ensues for Lin and her family. Nancy Huston, award-winning author of The Mark of the Angel, writes brilliantly here about the passage of time, the body’s vulnerability, and the solitude of creative endeavor. What results is a deeply felt novel that offers a disquieting but profoundly moving meditation on just what it means to be an artist.

Preț: 86.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 130

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.57€ • 17.30$ • 13.69£

16.57€ • 17.30$ • 13.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375709203

ISBN-10: 0375709207

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Vintage Intl.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375709207

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Vintage Intl.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

A native of Calgary and of New Hampshire, Nancy Huston now lives in Paris; she writes in both French and English. The author of nine novels and numerous works of nonfiction, she has won the Prix Goncourt des Lycéen, the Prix du Livre-Inter, the Prix Elle, and the Governor General’s Award for Fiction in French.

Extras

PART ONE

The Soloist

That body is out of her.

A girl, say the people whose hands are now skillfully manipulating tiny angular limbs and lumps of glistening sticky buttocks and hairy head down there, then plunging deep into the yawning chasm of Lin's body to extract the black-red pulsating form of living flesh that belongs to no one, neither to her nor to the child -- then they are sewing her.

Lin does not care what they do to her now. That body is out of her. It is on the roof of its empty house and its lips have fastened round her nipple and are sucking fast as heartbeat, fierce as sex. A person behaving like a real live baby and daughtering her. Such a wee wisp of a thing whereas it had weighed like a boulder in her gut. While the wolf was sleeping, bloated and ill from having gobbled down seven baby goats one after the other without so much as bothering to chew them, the nanny goat came to the rescue of her children: she slit open the wolf's stomach with a knife and all seven kids jumped out safe and sound, then they filled his stomach with stones and stitched it back up again and when the wolf awoke, oh my God . . . But here the stone has been replaced by a kid instead of the other way around, and the torn flesh is being sewed up and Lin is a mother. Not only that, but Derek is a father. His nervous futile fanning of her face and smoothing of her hair has ceased; now one of his hands is squeezing hers and he has laid the other gently on his daughter's minute white-clad back. So many monumental new terms coming into play here. A few seconds ago there was no such thing as daughter mother father and now there they are, these words have been violently promoted from cliches to Beethoven symphonies, choirs of angels, floods of sunlight. The nurse is still stitching and dabbing down there, the sting and pierce of the needle are pleasant to Lin, compared with the just-past hellish upheaval of self.

Once rinsed of womb muck and pressed dry with a towel, Angela's fine thin hair is blond. Her head nests in the crook of Lin's left arm as her lips pump imperiously to draw from Lin's breast the thin nourishing liquid which is not yet milk. Her eyes stare into Lin's eyes as though each second of staring brought with it as much newness and replenishment as each second of sucking.

Voraciously Angela gulps down the look in her mother's eyes.

The ward is a swarm of cries and coos and cuddles. Other mothers press small squalling mouths to dripping nipples. Get out of my happiness, thinks Lin.

Angela is the only baby on earth and Lin the only mother.

How could she not know to swab the stub of scabbed flesh at her own daughter's midriff?

In the shower, Lin soaps and scrubs her empty body, vigorously beneath the armpits, gingerly between the legs. She is still there. She did not die or become someone else. Not only is she still herself but she is also a mother. Not only is she still alive but someone else is also, totally, alive at the far end of the corridor and she can feel the tug of that person's life at her heartstrings. It is like falling in love only without the darkness, without the thrill and clutch of fear.

Angela's feet. Those same feet which a thousand times had kicked Lin soft-thud strangely in the stomach, bladder, intestines, lungs. Long curved toes, nearly invisible slits of toenails, wrinkles everywhere. Absurdly large coming at the end of such puny calves and thighs, absurdly small next to any pair of shoes. Except the pastel booties knit by Derek's mother, Violet, with ribbons slipped through the ankle stitches to tie them securely but despite the ribbons the great red feet keep pushing them off, the left one is always waving around naked and chill, undressed by the snug smug right.

Bathing her. Lin's left arm crooked beneath Angela's upper back, supporting her head, her right hand gently sponging the fat stomach, sponging the frog legs parted in fifth-position grand plie, sponging the unspeakably sweet sex. Angela's big eyes follow every twitch and twinkle of the face above her. And she is so at home in the tepid water, so ecstatically abandoned.

During her daughter's long spans of white sleep Lin often finds the clinic's exercise room empty and can lie splayed on its hardwood floor, contract-release relaxing, getting reaccustomed to being the only person in her body. Sometimes when she sits and bends, forward forward downward, drops of milk seep through her shirt and spatter her naked knees.

You'll be back on stage in no time, Mrs. Lhomond, the nurse says one day, upon seeing her emerge from the exercise room. Lin nods, radiant.

They slip the fabulous bulk of the Sunday Times into the stroller bag, where it almost upends their little girl. They laugh. They are inclined to laugh at the slightest pretext.

Angela is asleep, swaddled in woolen blankets, her eyes protected from the sun. On the park bench, as their hands are occupied and dirtied with the newspaper, they hold feet, legs twined.

Look at those families, says Lin after a while. I mean, just look at them.

The other babies are hopelessly pudgy, they are dressed in garish synthetic pinks and yellows and blues, to say nothing of the new green recently concocted by the clothing industry, the only green it had never in a million years entered nature's head to produce. Angela's clothes and blankets by contrast are shimmering mist, water lilies, cloud formations. All the babies over the age of one -- all the walking babies -- are monstrous: they look like circus giants or men on stilts, like adults pretending to be babies. Their mothers chitchat on benches, yell orders at their offspring and filch their cookies when their backs are turned.

Lin points.

You see? The woman's absorbed in feeding mashed bananas to her son and the man is watching teenaged girls swish by and looking sheepish. He's got to sit there feigning an interest in his chubby grubby offspring secretly he's thinking Jesus, if only I could slip through these bench slats here while Mathilda isn't looking . . .

The worst of it, says Derek, is that if he hadn't been such a funky dancer in the first place, pushing and pressing and breathing down Martha's neck and insisting on going all the way, there would have been no gurgling BillyBob Junior sitting in that there perambulator.

They kiss.

That would have been one empty pram, man, says Lin. A pity to leave it empty, says Derek, what with those aesthetically alternating white-and-yellow stripes and all.

They kiss.

But don't those wispy slips of girls make you wanna get up and go, too?

Oh . . . I waited a long time for perfection to come along, you know, says Derek.

If you can call that sort of behavior waiting, says Lin.

They kiss and kiss, their tongues in each other's mouths. Angela wakes and they rock her stroller gently, kissing and kissing.

The shit is fine. They compete to see which of them can wipe Angela's ass the cleanest the fastest. They kiss her white rump, rubbing their cheeks against her smooth-as-glass soft-as-silk skin. Angela's face is calm and serious when they change her.

Lin loves to watch her husband's hands, the hands of a philosophy professor, undo the snap buttons of her pajamas, pop pop pop all six of them, withdraw her great red feet and remove her soiled diaper, carefully part and clean the tiny folds of her vulva, wiping downward from sex to anus and never the reverse, powder her dry and rediaper her and slip her feet back into the pajama feet and do up the snap buttons again, all six of them click click click.

Her own inner flesh is raw and tender, her breasts swollen and blue-veined, she cannot yet take him inside the cave from which the baby burst but he is in no hurry, the sight of that volcano, that churning bleeding living knot of flesh, had awed him as the burning bush awed Moses so they float in sensual limbo, find pleasure with their mouths, fingers, skin, weep sometimes for no reason whatsoever.

With friends, they refer to Angela as they have always heard parents refer to their children: casually. Sometimes they even force themselves to complain about her feedings in the middle of the night. This nonchalance, they think, must be part of an enormous parently plot to keep nonparents in the dark.

Theresa arrives after breakfast three times a week, with her apron and house slippers in a plastic bag, to clean the dirt Lin and her family leave behind. She is Italian, in her forties. Some families, Theresa had told Lin, expect her to handwash soiled underwear, scrape pots and pans coated with burned-stiff week-old food, comb dog hairs out of cushions. Here it is fairly clean cleaning she has to do.

Lin is in her dance room, the spacious attic with its slants and rafters and skylights and wall of mirrors and hardwood floor, which was the first room she and Derek had renovated when they bought the house. She pulls on her thick old woolen socks with the heels and toes cut out of them. This is the first time.

Excited, she moves to the barre. Slowly opens and oils her joints. Yes she can again bend over from the waist with her legs straight and place her elbows on the floor. Yes she can again put her foot on the wall high above her head and press her face to her knee. Little by little her arms and legs lengthen and her back dilates -- she is a giant.

Usually after an hour of work she enters the place where it is no longer she who produces the dance but the dance that produces her, the dance that takes hold of her feet and arms and waist and spins and holds her, retains and releases her as it pleases.

Oh this silent thing, this contradiction in terms this transfiguration of body into soul this art of the perishable flesh this ephemerous eternity

But today the warmup is enough to drain her completely. At eleven o'clock she curls up in a corner of the dance room and draws a bath towel over her body.

They have found day care for Angela. Late each afternoon, either Lin or Derek is allowed to enter a roomful of little people and extract one of them as theirs and take it home.

Lin enters Angela's room and kneels on the floor next to her crib. She listens to the evenness of her daughter's breathing. All this is so good. Lin is never afraid that Angela will die in her sleep. She never hovers over her crib to make sure she has not stopped breathing.

Derek! cries Lin -- so loudly that Angela wakens with a start. Derek! She turned over in her crib! She turned over by herself, I swear it! I put her down on her back and now she's on her stomach -- come and see, come and see!

Lin and Derek join hands and prance around their daughter's bedroom. Her wobbly head raised, Angela watches them wide-eyed, uncertain whether the hubbub is a good or a bad sign.

They put her on her back again. She struggles, teeters, plops to her stomach.

They applaud wildly and put her on her back again.

But Angela is exhausted -- try as she might, kicking and straining, red-faced with fury, she cannot turn over a third time.

Rachel drops by with a gift of black pajamas for Angela, and Lin knows what this means; it is a reminder of the ancient love of death between the two of them, the penchant that had soldered them together for so many years. A shiver goes through her the first time she fastens the darkness round her daughter's nape of curls, but the result is irrefutable.

In high school they had recognized each other instantly: excellent grades, dark rings under the eyes, a keen taste for silence. Like a pair of sinister twins they had dressed in tight black clothes, been wan and drawn and pale and tense together, smoked fifty cigarettes a day and starved themselves to skeletal skinniness because they wished to hover at the very edge of existence, as close to the bone as possible. They had not asked to live and their interest in life was feigned and forced. If they absolutely had to live, they preferred to do so as quickly as possible and get it over with, so they worked themselves to the point of collapse in a state of frenzied indifference, Lin at her dance and Rachel at her Greek philosophers, desiring perfection only because it was tantamount to death. They ate skimpily and irregularly, smoked not despite but because of the fact they knew it was bad for them, especially Lin, preferring the poison of danger to the vapid complacency of good health, filling time to its utmost limit, getting up each day at dawn, eschewing naps and holidays, sensing nonetheless the scraping tick of seconds at their backs and resenting each of them individually.

It was not that their ideals had been tarnished -- no, they had never had ideals because they had never had mothers. Lin's had been whisked off to heaven by a brain hemorrhage when she was barely three, and Rachel's had turned from her in disgust the minute she had glimpsed her baby's sex -- a daughter could never replace the scholarly European uncles and cousins and grandfathers who had been gassed at Birkenau. Both girls had gone on living out of sheer inertia. They could not instinctively take care of their bodies because their bodies had always been handled by loveless females. They had learned slowly, as from a user's manual, the objective rules of what was good and bad for them, and usually did the latter. God did not exist, their fathers did not care, and there were as yet no husbands on the horizon; since no one exercised authority over them, they gradually themselves became authority incarnate, slave driver and slave strapped together in the same body, the same mind.

Rachel had remained true to their shared philosophy -- succeed in everything, believe in nothing. Lin had betrayed it.

She now believes in playing peek-a-boo with Angela. She does it wholeheartedly, whereas the agreement between her and Rachel was that they had no hearts.

Fifty times in a row, Angela covers her head with a towel and calls herself -- Aaaaa-laaaa! Fifty times in a row, Lin gently pulls the towel away. Fifty times in a row, Angela bursts into delighted laughter. And so does Lin, though they are not laughing for the same reasons.

In Rachel's eyes, she can see awareness of her betrayal but no reproach.

The Soloist

That body is out of her.

A girl, say the people whose hands are now skillfully manipulating tiny angular limbs and lumps of glistening sticky buttocks and hairy head down there, then plunging deep into the yawning chasm of Lin's body to extract the black-red pulsating form of living flesh that belongs to no one, neither to her nor to the child -- then they are sewing her.

Lin does not care what they do to her now. That body is out of her. It is on the roof of its empty house and its lips have fastened round her nipple and are sucking fast as heartbeat, fierce as sex. A person behaving like a real live baby and daughtering her. Such a wee wisp of a thing whereas it had weighed like a boulder in her gut. While the wolf was sleeping, bloated and ill from having gobbled down seven baby goats one after the other without so much as bothering to chew them, the nanny goat came to the rescue of her children: she slit open the wolf's stomach with a knife and all seven kids jumped out safe and sound, then they filled his stomach with stones and stitched it back up again and when the wolf awoke, oh my God . . . But here the stone has been replaced by a kid instead of the other way around, and the torn flesh is being sewed up and Lin is a mother. Not only that, but Derek is a father. His nervous futile fanning of her face and smoothing of her hair has ceased; now one of his hands is squeezing hers and he has laid the other gently on his daughter's minute white-clad back. So many monumental new terms coming into play here. A few seconds ago there was no such thing as daughter mother father and now there they are, these words have been violently promoted from cliches to Beethoven symphonies, choirs of angels, floods of sunlight. The nurse is still stitching and dabbing down there, the sting and pierce of the needle are pleasant to Lin, compared with the just-past hellish upheaval of self.

Once rinsed of womb muck and pressed dry with a towel, Angela's fine thin hair is blond. Her head nests in the crook of Lin's left arm as her lips pump imperiously to draw from Lin's breast the thin nourishing liquid which is not yet milk. Her eyes stare into Lin's eyes as though each second of staring brought with it as much newness and replenishment as each second of sucking.

Voraciously Angela gulps down the look in her mother's eyes.

The ward is a swarm of cries and coos and cuddles. Other mothers press small squalling mouths to dripping nipples. Get out of my happiness, thinks Lin.

Angela is the only baby on earth and Lin the only mother.

How could she not know to swab the stub of scabbed flesh at her own daughter's midriff?

In the shower, Lin soaps and scrubs her empty body, vigorously beneath the armpits, gingerly between the legs. She is still there. She did not die or become someone else. Not only is she still herself but she is also a mother. Not only is she still alive but someone else is also, totally, alive at the far end of the corridor and she can feel the tug of that person's life at her heartstrings. It is like falling in love only without the darkness, without the thrill and clutch of fear.

Angela's feet. Those same feet which a thousand times had kicked Lin soft-thud strangely in the stomach, bladder, intestines, lungs. Long curved toes, nearly invisible slits of toenails, wrinkles everywhere. Absurdly large coming at the end of such puny calves and thighs, absurdly small next to any pair of shoes. Except the pastel booties knit by Derek's mother, Violet, with ribbons slipped through the ankle stitches to tie them securely but despite the ribbons the great red feet keep pushing them off, the left one is always waving around naked and chill, undressed by the snug smug right.

Bathing her. Lin's left arm crooked beneath Angela's upper back, supporting her head, her right hand gently sponging the fat stomach, sponging the frog legs parted in fifth-position grand plie, sponging the unspeakably sweet sex. Angela's big eyes follow every twitch and twinkle of the face above her. And she is so at home in the tepid water, so ecstatically abandoned.

During her daughter's long spans of white sleep Lin often finds the clinic's exercise room empty and can lie splayed on its hardwood floor, contract-release relaxing, getting reaccustomed to being the only person in her body. Sometimes when she sits and bends, forward forward downward, drops of milk seep through her shirt and spatter her naked knees.

You'll be back on stage in no time, Mrs. Lhomond, the nurse says one day, upon seeing her emerge from the exercise room. Lin nods, radiant.

They slip the fabulous bulk of the Sunday Times into the stroller bag, where it almost upends their little girl. They laugh. They are inclined to laugh at the slightest pretext.

Angela is asleep, swaddled in woolen blankets, her eyes protected from the sun. On the park bench, as their hands are occupied and dirtied with the newspaper, they hold feet, legs twined.

Look at those families, says Lin after a while. I mean, just look at them.

The other babies are hopelessly pudgy, they are dressed in garish synthetic pinks and yellows and blues, to say nothing of the new green recently concocted by the clothing industry, the only green it had never in a million years entered nature's head to produce. Angela's clothes and blankets by contrast are shimmering mist, water lilies, cloud formations. All the babies over the age of one -- all the walking babies -- are monstrous: they look like circus giants or men on stilts, like adults pretending to be babies. Their mothers chitchat on benches, yell orders at their offspring and filch their cookies when their backs are turned.

Lin points.

You see? The woman's absorbed in feeding mashed bananas to her son and the man is watching teenaged girls swish by and looking sheepish. He's got to sit there feigning an interest in his chubby grubby offspring secretly he's thinking Jesus, if only I could slip through these bench slats here while Mathilda isn't looking . . .

The worst of it, says Derek, is that if he hadn't been such a funky dancer in the first place, pushing and pressing and breathing down Martha's neck and insisting on going all the way, there would have been no gurgling BillyBob Junior sitting in that there perambulator.

They kiss.

That would have been one empty pram, man, says Lin. A pity to leave it empty, says Derek, what with those aesthetically alternating white-and-yellow stripes and all.

They kiss.

But don't those wispy slips of girls make you wanna get up and go, too?

Oh . . . I waited a long time for perfection to come along, you know, says Derek.

If you can call that sort of behavior waiting, says Lin.

They kiss and kiss, their tongues in each other's mouths. Angela wakes and they rock her stroller gently, kissing and kissing.

The shit is fine. They compete to see which of them can wipe Angela's ass the cleanest the fastest. They kiss her white rump, rubbing their cheeks against her smooth-as-glass soft-as-silk skin. Angela's face is calm and serious when they change her.

Lin loves to watch her husband's hands, the hands of a philosophy professor, undo the snap buttons of her pajamas, pop pop pop all six of them, withdraw her great red feet and remove her soiled diaper, carefully part and clean the tiny folds of her vulva, wiping downward from sex to anus and never the reverse, powder her dry and rediaper her and slip her feet back into the pajama feet and do up the snap buttons again, all six of them click click click.

Her own inner flesh is raw and tender, her breasts swollen and blue-veined, she cannot yet take him inside the cave from which the baby burst but he is in no hurry, the sight of that volcano, that churning bleeding living knot of flesh, had awed him as the burning bush awed Moses so they float in sensual limbo, find pleasure with their mouths, fingers, skin, weep sometimes for no reason whatsoever.

With friends, they refer to Angela as they have always heard parents refer to their children: casually. Sometimes they even force themselves to complain about her feedings in the middle of the night. This nonchalance, they think, must be part of an enormous parently plot to keep nonparents in the dark.

Theresa arrives after breakfast three times a week, with her apron and house slippers in a plastic bag, to clean the dirt Lin and her family leave behind. She is Italian, in her forties. Some families, Theresa had told Lin, expect her to handwash soiled underwear, scrape pots and pans coated with burned-stiff week-old food, comb dog hairs out of cushions. Here it is fairly clean cleaning she has to do.

Lin is in her dance room, the spacious attic with its slants and rafters and skylights and wall of mirrors and hardwood floor, which was the first room she and Derek had renovated when they bought the house. She pulls on her thick old woolen socks with the heels and toes cut out of them. This is the first time.

Excited, she moves to the barre. Slowly opens and oils her joints. Yes she can again bend over from the waist with her legs straight and place her elbows on the floor. Yes she can again put her foot on the wall high above her head and press her face to her knee. Little by little her arms and legs lengthen and her back dilates -- she is a giant.

Usually after an hour of work she enters the place where it is no longer she who produces the dance but the dance that produces her, the dance that takes hold of her feet and arms and waist and spins and holds her, retains and releases her as it pleases.

Oh this silent thing, this contradiction in terms this transfiguration of body into soul this art of the perishable flesh this ephemerous eternity

But today the warmup is enough to drain her completely. At eleven o'clock she curls up in a corner of the dance room and draws a bath towel over her body.

They have found day care for Angela. Late each afternoon, either Lin or Derek is allowed to enter a roomful of little people and extract one of them as theirs and take it home.

Lin enters Angela's room and kneels on the floor next to her crib. She listens to the evenness of her daughter's breathing. All this is so good. Lin is never afraid that Angela will die in her sleep. She never hovers over her crib to make sure she has not stopped breathing.

Derek! cries Lin -- so loudly that Angela wakens with a start. Derek! She turned over in her crib! She turned over by herself, I swear it! I put her down on her back and now she's on her stomach -- come and see, come and see!

Lin and Derek join hands and prance around their daughter's bedroom. Her wobbly head raised, Angela watches them wide-eyed, uncertain whether the hubbub is a good or a bad sign.

They put her on her back again. She struggles, teeters, plops to her stomach.

They applaud wildly and put her on her back again.

But Angela is exhausted -- try as she might, kicking and straining, red-faced with fury, she cannot turn over a third time.

Rachel drops by with a gift of black pajamas for Angela, and Lin knows what this means; it is a reminder of the ancient love of death between the two of them, the penchant that had soldered them together for so many years. A shiver goes through her the first time she fastens the darkness round her daughter's nape of curls, but the result is irrefutable.

In high school they had recognized each other instantly: excellent grades, dark rings under the eyes, a keen taste for silence. Like a pair of sinister twins they had dressed in tight black clothes, been wan and drawn and pale and tense together, smoked fifty cigarettes a day and starved themselves to skeletal skinniness because they wished to hover at the very edge of existence, as close to the bone as possible. They had not asked to live and their interest in life was feigned and forced. If they absolutely had to live, they preferred to do so as quickly as possible and get it over with, so they worked themselves to the point of collapse in a state of frenzied indifference, Lin at her dance and Rachel at her Greek philosophers, desiring perfection only because it was tantamount to death. They ate skimpily and irregularly, smoked not despite but because of the fact they knew it was bad for them, especially Lin, preferring the poison of danger to the vapid complacency of good health, filling time to its utmost limit, getting up each day at dawn, eschewing naps and holidays, sensing nonetheless the scraping tick of seconds at their backs and resenting each of them individually.

It was not that their ideals had been tarnished -- no, they had never had ideals because they had never had mothers. Lin's had been whisked off to heaven by a brain hemorrhage when she was barely three, and Rachel's had turned from her in disgust the minute she had glimpsed her baby's sex -- a daughter could never replace the scholarly European uncles and cousins and grandfathers who had been gassed at Birkenau. Both girls had gone on living out of sheer inertia. They could not instinctively take care of their bodies because their bodies had always been handled by loveless females. They had learned slowly, as from a user's manual, the objective rules of what was good and bad for them, and usually did the latter. God did not exist, their fathers did not care, and there were as yet no husbands on the horizon; since no one exercised authority over them, they gradually themselves became authority incarnate, slave driver and slave strapped together in the same body, the same mind.

Rachel had remained true to their shared philosophy -- succeed in everything, believe in nothing. Lin had betrayed it.

She now believes in playing peek-a-boo with Angela. She does it wholeheartedly, whereas the agreement between her and Rachel was that they had no hearts.

Fifty times in a row, Angela covers her head with a towel and calls herself -- Aaaaa-laaaa! Fifty times in a row, Lin gently pulls the towel away. Fifty times in a row, Angela bursts into delighted laughter. And so does Lin, though they are not laughing for the same reasons.

In Rachel's eyes, she can see awareness of her betrayal but no reproach.

Recenzii

“Spare, elegant …. I can think of no other novel that so honestly and deeply explores the experience of the artist.” — Jeffrey Lent, author of In the Fall

“A sensitive, sweeping account of the difficulty of reconciling maternal and artistic callings”–Publishers Weekly

“A haunting story about an uncommon subject”–Library Journal

“One wakes from this novel as from a spell of urgent, slow-motion dreams. . . . Slow Emergencies is full of the elements of enchantment.” — The Washington Post

“Told simply and without pretense. . . . Huston deserves bravos for her portrayal of how motherhood devours the mother.”– Book

“A sensitive, sweeping account of the difficulty of reconciling maternal and artistic callings”–Publishers Weekly

“A haunting story about an uncommon subject”–Library Journal

“One wakes from this novel as from a spell of urgent, slow-motion dreams. . . . Slow Emergencies is full of the elements of enchantment.” — The Washington Post

“Told simply and without pretense. . . . Huston deserves bravos for her portrayal of how motherhood devours the mother.”– Book