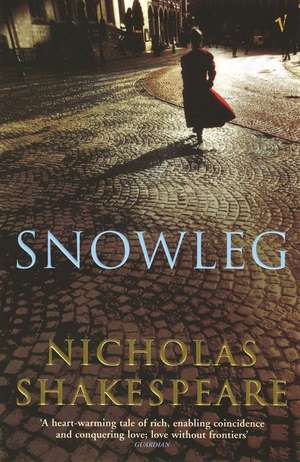

Snowleg

Autor Nicholas Shakespeareen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 ian 2005

Snowleg is a powerful love story that explores the close, fraught relationship between England and Germany, between a man who grows up believing himself to be a chivalrous English public schoolboy and a woman who tries to live loyally under a repressive regime.

Preț: 54.59 lei

Preț vechi: 107.01 lei

-49% Nou

Puncte Express: 82

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.45€ • 11.35$ • 8.78£

10.45€ • 11.35$ • 8.78£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-09 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 74.22 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780099466093

ISBN-10: 0099466090

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 128 x 199 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0099466090

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 128 x 199 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Recenzii

“Already my bet for this year’s Booker Prize. A superbly achieved and moving novel.”

—Giles Fodden, Guardian

“Snowleg is his finest book yet. Beautifully written, rich in character, it displays all the courage for which its hero so desperately wants to be recognized.”

—Economist

“This novel is one of the finest attempts in English to convey something of two very strange places which no longer appear on the map of Europe… Shakespeare has told a very skillful story.”

—Evening Standard

"This novel is one of the finest attempts in English to convey something of two very strange places which no longer appear on the map of Europe... Shakespeare has told a very skilful story" Evening Standard "Offers more than high romance: it is a portrait, and a good one, of the East Germany of the Stasi, with its bleakly beautiful landscapes, its casual betrayals, and its subtle capacity to dehumanise" Daily Telegraph "His finest book yet. Beautifully written, rich in character, it displays all the courage for which its hero so desperately wants to be recognised" Economist "A heart-warming tale of rich, enabling coincidence and conquering love; love without frontiers" Guardian "Elegant metaphors, striking insights, eidetic settings and sensitive renditions of character - Shakespeare's writing is of a high order. Impressive" Time Out

—Giles Fodden, Guardian

“Snowleg is his finest book yet. Beautifully written, rich in character, it displays all the courage for which its hero so desperately wants to be recognized.”

—Economist

“This novel is one of the finest attempts in English to convey something of two very strange places which no longer appear on the map of Europe… Shakespeare has told a very skillful story.”

—Evening Standard

"This novel is one of the finest attempts in English to convey something of two very strange places which no longer appear on the map of Europe... Shakespeare has told a very skilful story" Evening Standard "Offers more than high romance: it is a portrait, and a good one, of the East Germany of the Stasi, with its bleakly beautiful landscapes, its casual betrayals, and its subtle capacity to dehumanise" Daily Telegraph "His finest book yet. Beautifully written, rich in character, it displays all the courage for which its hero so desperately wants to be recognised" Economist "A heart-warming tale of rich, enabling coincidence and conquering love; love without frontiers" Guardian "Elegant metaphors, striking insights, eidetic settings and sensitive renditions of character - Shakespeare's writing is of a high order. Impressive" Time Out

Notă biografică

Nicholas Shakespeare was born in 1957. The son of a diplomat, much of his youth was spent in the Far East and South America. His novels have been translated into twenty languages. They include The Vision of Elena Silves, winner of the Somerset Maugham Award, Snowleg and The Dancer Upstairs, which was chosen by the American Libraries Association in 1997 as the year's best novel, and in 2001 was made into a film of the same name by John Malkovich. His most recent novel is Secrets of the Sea. He is married with two small boys and currently lives in Oxford.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

She led the way along the bridle path, through a field of blackspotted stones and blackberry bushes that glistened with rain. Peter’s favourite walk.

They climbed in silence. Near the summit they came to a steep chalk verge dotted with yellow and red bee-orchids – “one of the few places in England where they grow”, according to his father. Once, taking a specimen to draw, his father had found embedded in the chalk a twisted scrap of aluminium, the relic, he maintained, of the Heinkel that had blazed into the ridge in the last months of the war. He kept it on a shelf in his studio, a precious metal flower.

At the lookout on the ridge – which Peter for ever after dubbed “Revelation Hill” – his mother paused.

The Friday before, Peter sat in Mugging Hall waiting to hear his name.

“Liptrot?”

“Sum.”

“Leadley?”

“Sum.”

“Hithersay?”

“Sum.” His presence confirmed, he drew the tangerine curtain of his “toyes”, the wooden stall – a jumble of horsebox, Arab tent and cupboard – that encompassed his private world away from home. He was meant to be writing an essay on Henry VIII’s secession from Rome in preparation for History A level. Instead, he listened, on headphones, to Morrison Hotel, while his eyes drank in the freckled young woman with a thin fox’s face pinned to his wall. The first woman to catch his fancy.

Peter had boarded at Southgate House since the age of twelve. It had taken him until this, his fourth year, not to feel alienated by its customs and chronically homesick. His school – St Cross College, outside Winchester – had its own confusing language in which something desirable, such as the image on his wall, was known as “cud”. Parents were “pitch-up”, and when walking between his House and classroom it was compulsory to wear a “strat”, a straw boater bought at phenomenal expense from Gieves & Hawkes in Winchester that served as a barometer, according to its state of disintegration and width of hatband, of a boy’s seniority. Then there was the “tub-room”, with its high-backed Edwardian tin baths of a sort Peter had never seen outside the school except at a plasterer’s in Salisbury. At St Cross you measured your progress towards manhood also by your ability to lift – and tip out – the weight of your dirty bathwater. When he was twelve, Peter had needed both hands. Now, at almost sixteen, he could empty his tub with one finger.

On those first Sunday afternoons, to escape the torpor that descended on his House and sharpened the smells of instant coffee and rancid milk and locker-room mud and the thick grey whiff of masturbation, Peter would wander beside the Itchen with no sense of connection. Four years on, this fretfulness had diminished. He had grown to admire the flint and brick buildings which he could see from the riverbanks, the beauty of worn stone and ritual, the emerald playing-fields which extended into water meadows that Keats had written a poem about. On these days he felt at one with St Cross, involved.

Only later did Peter appreciate the depth and saturation of the school’s Englishness. When he did at last consider it, he realised there were hardly any boys from outside the southern half of England, let alone from overseas. One exception was Tweed, a Greek boy in his House whose parents were so desperate to join the English Establishment that they had changed his name from Nikoliades. Apart from Tweed, a wealthy mathematician with weirdly blond hair and a loud voice, Peter had encountered few foreigners.

His own parents weren’t well-off. His father’s distress at the sight of a bill made Peter overly conscious of the fact that had he not won a scholarship they couldn’t have afforded the fees. Certainly they weren’t able to afford the same kind of school for Rosalind, who, not being “academically minded” as they put it, attended the local comprehensive together with her friend Camilla Rickards.

“‘At first flash of Eden, we rush down to the sea, / Standing there on freedom’s shore.’”

One part Rimbaud and two parts nonsense, it still gave him a buzz. Eyes closed, dreaming of Camilla, he didn’t hear the curtain snap open. Seconds passed before Peter was aware of Mr Tamlyn. Briar clamped in mouth, his housemaster surveyed the wooden stall.

“Sir!”

Peter struggled to turn off his tape recorder while Mr Tamlyn’s waxy gaze roamed over the “Abolish the House of Lords” sticker, took in the electric filament in his mug and moved up the photographs stuck on the toyes wall: Jim Morrison, Steve McQueen in The Great Escape – and the women he craved to sleep with. Like Camilla, whose meek response on learning that Peter went to St Cross – “You must be clever” – inspired the wild grain of hope that she would be the one to ease his sexual desire.

Out of place at the centre of this gallery was Peter’s No. 1 hero, and the most prosaic. St Cross owned a copy of the Malory manuscript, and this explained the presence on his wall, next to a tanned young woman in a rubber swimsuit advertising Lamb’s Navy rum, of a reproduction of a Victorian painting of Sir Bedevere, last Knight of the Table Round and scourge of the Germanic hordes who had dared to threaten England.

Peter was drawn to the knight whom the dying Arthur entrusted with his sword. He recognised elements of himself in Bedevere, someone who was not a natural leader but who had pockets of this quality which allowed him to advance and retreat. He envied Bedevere his experience of the miraculous: the hand that dolphined out of the water – brief confirmation of a calm and secure order – before it sank back into the depths, to vanish for ever. He loved the story and sometimes wished he might come across a dragon-threatened damsel so that he could display a courage which his surface hid.

Rosalind mocked his obsession. She preferred Bedevere as played by Terry Jones in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a film which their parents had taken them to see at Christmas. She was twelve, but considered it juvenile of her brother to have “a comic-book fart as a pin-up”.

And yet if Peter believed in anything, it was in the paternal spirit embodied by King Arthur and his chivalric knights. The fact that the school – itself founded in the fourteenth century – had custody of the manuscript which told their stories consoled him hugely.

Without divulging by one facial muscle his opinion of bold Sir Bedevere, Camilla Rickards or the desirability of the House of Lords, Mr Tamlyn removed the damp pipe stem from his mouth.

“Your mother’s on the telephone, Hithersay.”

Peter followed his housemaster down the red-tiled corridor and through a studded swing door. Into the only part of Southgate that resembled a normal house.

“Take your time,” Mr Tamlyn said, his voice kind. It was always stressful to receive a call.

Peter went into the study. The telephone on the desk reeked of “Malvern mixture”.

“Hello?” uncertain whether to sit in his housemaster’s swivel chair.

“Darling, it’s Mummy. Your grandfather’s not very well.” She spoke quickly. “Don’t worry, he’s absolutely fine at the moment. But instead of us taking you out on Sunday, it might be better if you came home.”

He started to ask for more details, but she cut him off. “I’ve spoken to Mr Tamlyn and he agrees. It would give your grandfather enormous pleasure if he could see you on your birthday. We can have a lovely picnic.”

Peter was walking back into Hall when a curtain twitched and a face stuck out: close-set eyes, jutting nose, the corners of a mouth raised in an expression of crafty hope.

“Anything wrong?”

“No, Leadley.”

“Well, Hithers? What was it about?” Leadley persisted. His family owned a substantial estate 3 miles from Peter’s parents. “Your pitch-up OK?”

“If you must know, I’ve been invited to a really smart party.”

He continued towards his toyes, a short Achilles tendon causing the bounce in his step that people sometimes mistook for good cheer.

For the two days following his mother’s call, Peter lost himself in the curriculum. Routine pulled him back from introspection. Worries about his grandfather faded.

On Saturday he played cricket on Lavender Meads, his favourite pitch. He took three wickets and scored 54 with the Slazenger bat his father had given him for Christmas. An hour after being caught at slip, he was sent out as a temporary substitute for an injured fielder and in the very next over sparked thunderous applause when a ball he threw in from the boundary hit the stumps. Delighted to have run out Leadley, he retreated to his position on the edge of the river, “saving four”, as the visiting school captain had instructed him to do.

The Itchen here was known as Old Barge and this was a dream of long waving weeds, the occasional trout lying like a torpedo in the depths, particularly under the bridge beside the playing field. Standing in the weeds, an untidy figure cast out a line in an effortless harmony of rhythm and balance.

“Brodie!”

Brodie, eyes on the water, didn’t hear.

Back on the pitch, a new batsman occupied the crease. Peter knew that he ought to walk in, but he lingered to watch Brodie cast again. Emboldened by his unexpectedly accurate throw, by six centuries of chalk streams and certainty and Englishness, he looked at where the plump trout flared against the current and tried to work out where he would pitch the sword.

“How’s school?” His father stood by the ticket gate. Curly grey hair, deep-set eyes, yellow cravat at his throat.

“Good,” said Peter, who felt a rush of affection as soon as he saw him. He had inherited certain of his mother’s looks and bothered gestures, but felt closer to his father. “I got a fifty yesterday.”

“Oh, that’s splendid. But you aren’t going to snare me into another Fathers’ Match?” Last time, he was out first ball.

“I’ll find an excuse,” grinned Peter, and put an arm around his father’s shoulder, breathing in that familiar, encompassing smell, a blend of printer’s ink and hopefulness.

Rodney had to stand on tiptoe to return his son’s embrace. “Happy birthday.” And then, a little regretfully, “Taller than ever.”

“Where’s Mummy?”

“Making you a cake.”

“Rosalind?”

“She’s dying to beat you at Scrabble.”

Not until the Rover turned out of the station did Peter ask about his grandfather.

“He’s not awfully well. Last Sunday, your mother found him lying on his floor. He didn’t know who he was. He’s been quite confused since then. But yesterday he got up and talked about going to the pub. Doctor Badcock thinks it’s time we started thinking about putting him into some sort of care.”

“And?”

“Well, you can imagine. He wants to die in his own sheets and your mother has promised. Anyway, see for yourself. He’s coming for tea.”

They drove up Tisbury High Street and as a roof flashed past Peter couldn’t help thinking of the old man lying in bed. His grandfather had been born at a time when if anyone living beside this road fell seriously ill, straw would be scattered thickly outside the house to dull the noise of horses’ hoofs and wagon wheels. This morning, opposite the shoe-shop, two men sat on their motorbikes and adjusted the straps on their helmets.

The Rover turned right after the post office and headed east towards Sutton Mandeville. Narrow lanes and tall hedgerows opening at intervals into wide downs where his father took him bird-watching. The Nadder glinted at the bottom of a shallow valley and in fields on either side the chalky soil glowed up through grass and lines of beech. Walking with his father on the edge of that river, Peter had come across his first plover’s nest. “See, the eggs are all pointing towards the middle. That means the chicks will soon be hatched.”

He turned to look back at the river. On the rear seat was a camera case and tripod. “Dad, what’s that camera for?”

“Ah, yes, well. Didn’t Mummy tell you?” As was his habit when under pressure, his father scratched at the large, inflamed bump that the cravat concealed. He called the unsightly goitre his “Derbyshire neck” and attributed it to the limestone in the water around Tansley where he had grown up.

“No,” said Peter. “She hasn’t told me anything.”

“I’ve become a photographer. Nothing fancy. Weddings, portraits, that kind of thing. But it makes a lot of sense – if I’m doing the invitations. Two birds with one stone and all that.” He gave a sad, light laugh. “Guess who I’m photographing next week?”

“I’m no good at guessing, Daddy.”

“Port Regis.”

“The school?”

“The whole school. Tell Mr Tamlyn. Maybe he’d like a House photo of Southgate. Tell him I’ll give him a discount.”

Minutes later, the Rover turned through gates Peter had never seen closed, into the white gravel drive, and stopped outside the house.

His parents didn’t have the means to live in London after Peter was born and moved to the “Wet country”, as Rodney dubbed the rain-soaked countryside south of Salisbury. Here, in a stone tithe-barn, Rodney clung to the lifeline offered by commercial art, earning a living of sorts designing letterheads and bookplates and invitations to parties, weddings and funerals.

Despite a coolness in the air, the French windows were open. From inside came the sound of a piano.

Peter rolled up his window and they sat for a moment, neither seeming to want to leave the car. Large insects moved in and out of the foxgloves and everywhere it was green and lush. His eyes tracked a hobby across the lawn and the sight of the swing suspended on blue ropes from the chestnut tree brought back another birthday. He was eight when his father had put up the swing. Suddenly, now, he wanted nothing so much as to feel a hand on his back, propelling him into the sky.

The hobby flitted to the roof of the stable that was his father’s studio, paused on the gutter, and flew off over the fields to the steep ridge beyond. The long hill, stretching from Salisbury to Shaftesbury, had a Roman ox-drive along the top. Peter didn’t know its name, but on summer days, when the wind was right, they would go up there and reel out a kite.

“Doesn’t look too promising.” His father, hand on door, glanced at the dark clouds bunching over the summit, and got out.

And still the music poured from the living room. His mother had hung on to the piano after she stopped singing. She was a first-rate pianist from her family’s point of view, but she was never going to sing again.

“I do hope Grandpa recovers,” Peter said to his father over the car roof. “Poor Mummy sounds seriously tense.”

“Go and talk to Ros,” said his father in a tender voice and went to put away his camera.

In the kitchen, Rosalind stirred a pot. Peter crept towards the stove. On the antique oak table where his mother’s pots had rested and burned circles, there were marks left with a blunt knife that mimicked his grandfather’s face.

But she heard him and spun around, and in a Monty Python voice said: “And that, my liege, is how we know the earth to be banana-shaped.” She licked the wooden spoon and made a musketeer’s lunge at his chest. He parried the spoon, seized her about the waist.

“Has Mummy told you? I have a Holy Grail to whit to woo, too.” She pulled away, smoothed back a stubborn blonde curl, and said, very seriously: “I’m going to become a gourmet chef.”

“Of course you are.”

Being at home, Rosalind was first in line in the epic food battle with their mother.

“Happy birthday, Bedevere,” giving him an asparagus-scented kiss.

From next door came their mother’s staccato rendering of the Goldberg Variations. Her voice might have gone, but her music was unstoppable.

“She’s bought you a present you won’t forget,” Rosalind teased, with the same inflexion as their father.

“What is it?”

“Not exactly something you can take back to school with you.”

“Have you heard from Camilla?”

“Yes,” slyly. “She sent you a message.”

“Well?”

“She wants to invite you to a party with Luke.”

“Luke?”

She wiggled her index finger in a way calculated to irritate. “Her BOYFRIEND.”

“Peter!”

Peter hadn’t heard the music stop. His mother wore a long saffron dress, a hand-me-down from one of his nannies, and her man’s watch, always slipping on her thin wrist.

“How long have you been here?” looking with a puzzled expression at the watch. Peter had given up asking why she insisted on wearing it. Never for a day had it kept the right time.

“Only a minute.”

They kissed. He put his hand on her shoulder and she tensed, drawing back to look at him. “Happy birthday, darling,” she said a little sadly, the same regretful tone as his father. She smelled of the French perfume that she always put on for special occasions, and he wondered for one ghastly moment if she had invited Leadley’s parents to lunch.

“I just hope it doesn’t rain, that’s all. What do you think, Rodney?” She placed all her faith in picnics.

He had just come into the room. “I don’t think it’ll rain,” and turned his inattention to the window. Next second, the heavens opened.

They had Rosalind’s vichyssoise in the dining room, then an asparagus quiche. His mother had chosen his favourite food, spoiling him, and he drank too much red wine.

He felt his father watching. He was aware of a quiet unrest in him and, when he thought about it afterwards, a premonition of something final.

The rain went on until they were eating strawberries and then the sun came out.

“Darling,” said his mother, rather nervous, as if testing a blade. “Can I show you something?”

“Mummy, the cake! Don’t forget the cake’s in the oven,” Rosalind said.

“Oh, God.”

His mother went into the kitchen and moments later he heard her going upstairs. When she came back she was clutching a photograph album he had never seen before. She sat beside him at the table and opened it: calf-bound, blue, full of images stuck down with white triangles, all of an odd-looking boy. Holding a cricket bat in a communal garden. Leaning from a pram. In christening robes.

“Look at those eyes – huge – always watering.”

He yawned. Why was she doing this?

From somewhere up in the house came a yap.

She moved her chair closer. Turning the wide pages, she told Peter that the boy was him. A fearer of dragons who had to ask their permission to get up in the mornings. The sun wasn’t yet hot enough for her face to be trickling with sweat. Some sort of expectation was making her nervous.

She went on speaking, but in a voice he hadn’t heard before. What she was telling him was beyond the furl of his understanding. Peter found the images far from reassuring. This was not a person he recognised, the boy with huge eyes. And why had his mother hidden this album all these years? He felt intruded on.

“Mummy!” he protested, and struggled against his mother’s arm around his shoulders. It was probably the cake making her morbid. She hated to cook, and had spent the whole morning preparing it.

“Wait.” In the same strange, needy tone she told him that he had been born one tea-time during a cold summer shortly before the Berlin Wall went up.

Pretending to look at the album, Peter studied the watch almost at her elbow. Even allowing for a spectacular margin of error, his train didn’t leave for another three hours. “You ought to get a new watch,” he said.

“I’m quite happy with this one, thank you.”

“Who’s that?” He craned forward, interested for the first time.

“That’s me in the Wigmore Hall, the year I went to Leipzig.”

She had trained as a singer in Manchester and was poised for a career with the BBC when something happened, Peter wasn’t sure what. The photograph showed a frizzy-haired young woman, firm shoulders in a long piqué dress, singing with an expression that she had lost.

In an otherwise crotchety cosmology, his mother had certain areas of tolerance. Unusual for one of her generation, she had a soft spot for Germans. The reminder of Leipzig gave her a second wind.

“Do you know what they called the Wigmore Hall before the First World War?” she went on tenaciously. “The Bechstein Hall. It was founded by Germans for German musicians.” She made a finger-crossing gesture. “That’s how close we used to be. Anglo- Saxons! I don’t care what Grandpa says. For centuries, the Germans have been England’s natural allies in Europe.”

“And didn’t the Connaught used to be the Coburg? And didn’t America very nearly choose German as its official language?” said his father helpfully, a hand burrowing under his cravat.

She exchanged a grateful glance, but it was Peter she had to convince. “You simply cannot imagine the Germanophobia,” she said, her enthusiasm shifting from the album to encompass in one bound a nation. “Even in the ’20s, Schubert Lieder, when sung in London, were sung in French.” She touched his arm. “And to think that we owe them our Royal Family, our religion, to say nothing of our music.”

“Come on, Peter.” The conversation was boring Rosalind. “Let’s play Scrabble.” And tugged at his hand, eyes plaintive under the stubborn curls.

Another yap.

“Why don’t we go for a walk?” Flustered, his mother brushed a lock of hair from his temples in the way that used to infuriate him as a boy. “And then you can have your present.”

“I’m not going for a walk,” said Peter.

“No, he’s coming with me,” piped up Rosalind.

“Rosalind!” From the end of the table, their father’s tone categorical in a way that Peter hadn’t often heard.

“Dear, maybe you could begin the washing-up.”

“Peter never does the washing-up,” Rosalind complained, spitting a strawberry onto her palm. “Ever.”

Rodney looked at Peter. “I think you should go. Do this for me.” And to his wife: “Henrietta. I really think. Now.”

Peter burst out: “What’s going on? It’s something about you, isn’t it? You’re having an affair. You’re getting divorced. You’re ill. Does Rosalind know?”

“I’m not ill. No affair. Just go for a walk. Go with your mother.”

Often at night when he couldn’t sleep Peter sifted his English childhood, beginning with the dragons under his bed and proceeding to the walk along the ox-drive and his mother’s revelation. A life-altering secret smelling of blackberry bushes after rain and causing a beating in his blood as if a large bird was taking off in the burrow of his chest.

In his memory, they climbed towards a summit fuzzy with rain. Towards the wreckage of the aeroplane and a body never discovered, just an iridescent slick for the Nadder mayflies to hatch on. But the sun, as it happened, was shining.

When they got to the top, she applied lipstick and adjusted her scarf, buttoning every single button of her coat.

“It’s turning into a lovely afternoon, but so chilly. Are you covered up? Look at that open neck of yours. Why didn’t you bring your scarf? I hope you don’t run around St Cross like that.”

A flint road led like vertebrae over the cornfields. She had been stumbling along it for five minutes when she stopped, already breathless.

“As you so often point out, I do have a knack for filing away things I prefer not to think about.” She fixed her watery green eyes on the sky. Her words flat and giving the impression she had rehearsed them. “You could describe it as a blockage of some kind. Or an inability to grapple with ‘personal issues’, as Rodney calls them. But I’m starting to talk about myself, and you need to know about Peter.”

She’s speaking of me as if I’m not here, he thought. Is she going nutty like her father? He yielded to an irritable blankness: “What do I need to know?”

“Not you, my love, not you,” she murmured. She rotated the watch on her wrist in a purposeless way and said: “Rodney’s not your father.”

Peter was aware of a bird’s shadow on the damp grass and something tearing inside.

“Your father’s someone else.”

“You mean I’m adopted?” he heard himself say.

“No, no, I’m your mother. In every other sense Rodney is your father. We met when you were six months old. Here, let’s sit down. I can say it better sitting down.”

They found a patch of grass where she began to explain that Peter’s father was not the affable and diffident Englishman to whom she had been married for 15 years, but an East German political prisoner whom she had known for hardly a day.

She led the way along the bridle path, through a field of blackspotted stones and blackberry bushes that glistened with rain. Peter’s favourite walk.

They climbed in silence. Near the summit they came to a steep chalk verge dotted with yellow and red bee-orchids – “one of the few places in England where they grow”, according to his father. Once, taking a specimen to draw, his father had found embedded in the chalk a twisted scrap of aluminium, the relic, he maintained, of the Heinkel that had blazed into the ridge in the last months of the war. He kept it on a shelf in his studio, a precious metal flower.

At the lookout on the ridge – which Peter for ever after dubbed “Revelation Hill” – his mother paused.

The Friday before, Peter sat in Mugging Hall waiting to hear his name.

“Liptrot?”

“Sum.”

“Leadley?”

“Sum.”

“Hithersay?”

“Sum.” His presence confirmed, he drew the tangerine curtain of his “toyes”, the wooden stall – a jumble of horsebox, Arab tent and cupboard – that encompassed his private world away from home. He was meant to be writing an essay on Henry VIII’s secession from Rome in preparation for History A level. Instead, he listened, on headphones, to Morrison Hotel, while his eyes drank in the freckled young woman with a thin fox’s face pinned to his wall. The first woman to catch his fancy.

Peter had boarded at Southgate House since the age of twelve. It had taken him until this, his fourth year, not to feel alienated by its customs and chronically homesick. His school – St Cross College, outside Winchester – had its own confusing language in which something desirable, such as the image on his wall, was known as “cud”. Parents were “pitch-up”, and when walking between his House and classroom it was compulsory to wear a “strat”, a straw boater bought at phenomenal expense from Gieves & Hawkes in Winchester that served as a barometer, according to its state of disintegration and width of hatband, of a boy’s seniority. Then there was the “tub-room”, with its high-backed Edwardian tin baths of a sort Peter had never seen outside the school except at a plasterer’s in Salisbury. At St Cross you measured your progress towards manhood also by your ability to lift – and tip out – the weight of your dirty bathwater. When he was twelve, Peter had needed both hands. Now, at almost sixteen, he could empty his tub with one finger.

On those first Sunday afternoons, to escape the torpor that descended on his House and sharpened the smells of instant coffee and rancid milk and locker-room mud and the thick grey whiff of masturbation, Peter would wander beside the Itchen with no sense of connection. Four years on, this fretfulness had diminished. He had grown to admire the flint and brick buildings which he could see from the riverbanks, the beauty of worn stone and ritual, the emerald playing-fields which extended into water meadows that Keats had written a poem about. On these days he felt at one with St Cross, involved.

Only later did Peter appreciate the depth and saturation of the school’s Englishness. When he did at last consider it, he realised there were hardly any boys from outside the southern half of England, let alone from overseas. One exception was Tweed, a Greek boy in his House whose parents were so desperate to join the English Establishment that they had changed his name from Nikoliades. Apart from Tweed, a wealthy mathematician with weirdly blond hair and a loud voice, Peter had encountered few foreigners.

His own parents weren’t well-off. His father’s distress at the sight of a bill made Peter overly conscious of the fact that had he not won a scholarship they couldn’t have afforded the fees. Certainly they weren’t able to afford the same kind of school for Rosalind, who, not being “academically minded” as they put it, attended the local comprehensive together with her friend Camilla Rickards.

“‘At first flash of Eden, we rush down to the sea, / Standing there on freedom’s shore.’”

One part Rimbaud and two parts nonsense, it still gave him a buzz. Eyes closed, dreaming of Camilla, he didn’t hear the curtain snap open. Seconds passed before Peter was aware of Mr Tamlyn. Briar clamped in mouth, his housemaster surveyed the wooden stall.

“Sir!”

Peter struggled to turn off his tape recorder while Mr Tamlyn’s waxy gaze roamed over the “Abolish the House of Lords” sticker, took in the electric filament in his mug and moved up the photographs stuck on the toyes wall: Jim Morrison, Steve McQueen in The Great Escape – and the women he craved to sleep with. Like Camilla, whose meek response on learning that Peter went to St Cross – “You must be clever” – inspired the wild grain of hope that she would be the one to ease his sexual desire.

Out of place at the centre of this gallery was Peter’s No. 1 hero, and the most prosaic. St Cross owned a copy of the Malory manuscript, and this explained the presence on his wall, next to a tanned young woman in a rubber swimsuit advertising Lamb’s Navy rum, of a reproduction of a Victorian painting of Sir Bedevere, last Knight of the Table Round and scourge of the Germanic hordes who had dared to threaten England.

Peter was drawn to the knight whom the dying Arthur entrusted with his sword. He recognised elements of himself in Bedevere, someone who was not a natural leader but who had pockets of this quality which allowed him to advance and retreat. He envied Bedevere his experience of the miraculous: the hand that dolphined out of the water – brief confirmation of a calm and secure order – before it sank back into the depths, to vanish for ever. He loved the story and sometimes wished he might come across a dragon-threatened damsel so that he could display a courage which his surface hid.

Rosalind mocked his obsession. She preferred Bedevere as played by Terry Jones in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a film which their parents had taken them to see at Christmas. She was twelve, but considered it juvenile of her brother to have “a comic-book fart as a pin-up”.

And yet if Peter believed in anything, it was in the paternal spirit embodied by King Arthur and his chivalric knights. The fact that the school – itself founded in the fourteenth century – had custody of the manuscript which told their stories consoled him hugely.

Without divulging by one facial muscle his opinion of bold Sir Bedevere, Camilla Rickards or the desirability of the House of Lords, Mr Tamlyn removed the damp pipe stem from his mouth.

“Your mother’s on the telephone, Hithersay.”

Peter followed his housemaster down the red-tiled corridor and through a studded swing door. Into the only part of Southgate that resembled a normal house.

“Take your time,” Mr Tamlyn said, his voice kind. It was always stressful to receive a call.

Peter went into the study. The telephone on the desk reeked of “Malvern mixture”.

“Hello?” uncertain whether to sit in his housemaster’s swivel chair.

“Darling, it’s Mummy. Your grandfather’s not very well.” She spoke quickly. “Don’t worry, he’s absolutely fine at the moment. But instead of us taking you out on Sunday, it might be better if you came home.”

He started to ask for more details, but she cut him off. “I’ve spoken to Mr Tamlyn and he agrees. It would give your grandfather enormous pleasure if he could see you on your birthday. We can have a lovely picnic.”

Peter was walking back into Hall when a curtain twitched and a face stuck out: close-set eyes, jutting nose, the corners of a mouth raised in an expression of crafty hope.

“Anything wrong?”

“No, Leadley.”

“Well, Hithers? What was it about?” Leadley persisted. His family owned a substantial estate 3 miles from Peter’s parents. “Your pitch-up OK?”

“If you must know, I’ve been invited to a really smart party.”

He continued towards his toyes, a short Achilles tendon causing the bounce in his step that people sometimes mistook for good cheer.

For the two days following his mother’s call, Peter lost himself in the curriculum. Routine pulled him back from introspection. Worries about his grandfather faded.

On Saturday he played cricket on Lavender Meads, his favourite pitch. He took three wickets and scored 54 with the Slazenger bat his father had given him for Christmas. An hour after being caught at slip, he was sent out as a temporary substitute for an injured fielder and in the very next over sparked thunderous applause when a ball he threw in from the boundary hit the stumps. Delighted to have run out Leadley, he retreated to his position on the edge of the river, “saving four”, as the visiting school captain had instructed him to do.

The Itchen here was known as Old Barge and this was a dream of long waving weeds, the occasional trout lying like a torpedo in the depths, particularly under the bridge beside the playing field. Standing in the weeds, an untidy figure cast out a line in an effortless harmony of rhythm and balance.

“Brodie!”

Brodie, eyes on the water, didn’t hear.

Back on the pitch, a new batsman occupied the crease. Peter knew that he ought to walk in, but he lingered to watch Brodie cast again. Emboldened by his unexpectedly accurate throw, by six centuries of chalk streams and certainty and Englishness, he looked at where the plump trout flared against the current and tried to work out where he would pitch the sword.

“How’s school?” His father stood by the ticket gate. Curly grey hair, deep-set eyes, yellow cravat at his throat.

“Good,” said Peter, who felt a rush of affection as soon as he saw him. He had inherited certain of his mother’s looks and bothered gestures, but felt closer to his father. “I got a fifty yesterday.”

“Oh, that’s splendid. But you aren’t going to snare me into another Fathers’ Match?” Last time, he was out first ball.

“I’ll find an excuse,” grinned Peter, and put an arm around his father’s shoulder, breathing in that familiar, encompassing smell, a blend of printer’s ink and hopefulness.

Rodney had to stand on tiptoe to return his son’s embrace. “Happy birthday.” And then, a little regretfully, “Taller than ever.”

“Where’s Mummy?”

“Making you a cake.”

“Rosalind?”

“She’s dying to beat you at Scrabble.”

Not until the Rover turned out of the station did Peter ask about his grandfather.

“He’s not awfully well. Last Sunday, your mother found him lying on his floor. He didn’t know who he was. He’s been quite confused since then. But yesterday he got up and talked about going to the pub. Doctor Badcock thinks it’s time we started thinking about putting him into some sort of care.”

“And?”

“Well, you can imagine. He wants to die in his own sheets and your mother has promised. Anyway, see for yourself. He’s coming for tea.”

They drove up Tisbury High Street and as a roof flashed past Peter couldn’t help thinking of the old man lying in bed. His grandfather had been born at a time when if anyone living beside this road fell seriously ill, straw would be scattered thickly outside the house to dull the noise of horses’ hoofs and wagon wheels. This morning, opposite the shoe-shop, two men sat on their motorbikes and adjusted the straps on their helmets.

The Rover turned right after the post office and headed east towards Sutton Mandeville. Narrow lanes and tall hedgerows opening at intervals into wide downs where his father took him bird-watching. The Nadder glinted at the bottom of a shallow valley and in fields on either side the chalky soil glowed up through grass and lines of beech. Walking with his father on the edge of that river, Peter had come across his first plover’s nest. “See, the eggs are all pointing towards the middle. That means the chicks will soon be hatched.”

He turned to look back at the river. On the rear seat was a camera case and tripod. “Dad, what’s that camera for?”

“Ah, yes, well. Didn’t Mummy tell you?” As was his habit when under pressure, his father scratched at the large, inflamed bump that the cravat concealed. He called the unsightly goitre his “Derbyshire neck” and attributed it to the limestone in the water around Tansley where he had grown up.

“No,” said Peter. “She hasn’t told me anything.”

“I’ve become a photographer. Nothing fancy. Weddings, portraits, that kind of thing. But it makes a lot of sense – if I’m doing the invitations. Two birds with one stone and all that.” He gave a sad, light laugh. “Guess who I’m photographing next week?”

“I’m no good at guessing, Daddy.”

“Port Regis.”

“The school?”

“The whole school. Tell Mr Tamlyn. Maybe he’d like a House photo of Southgate. Tell him I’ll give him a discount.”

Minutes later, the Rover turned through gates Peter had never seen closed, into the white gravel drive, and stopped outside the house.

His parents didn’t have the means to live in London after Peter was born and moved to the “Wet country”, as Rodney dubbed the rain-soaked countryside south of Salisbury. Here, in a stone tithe-barn, Rodney clung to the lifeline offered by commercial art, earning a living of sorts designing letterheads and bookplates and invitations to parties, weddings and funerals.

Despite a coolness in the air, the French windows were open. From inside came the sound of a piano.

Peter rolled up his window and they sat for a moment, neither seeming to want to leave the car. Large insects moved in and out of the foxgloves and everywhere it was green and lush. His eyes tracked a hobby across the lawn and the sight of the swing suspended on blue ropes from the chestnut tree brought back another birthday. He was eight when his father had put up the swing. Suddenly, now, he wanted nothing so much as to feel a hand on his back, propelling him into the sky.

The hobby flitted to the roof of the stable that was his father’s studio, paused on the gutter, and flew off over the fields to the steep ridge beyond. The long hill, stretching from Salisbury to Shaftesbury, had a Roman ox-drive along the top. Peter didn’t know its name, but on summer days, when the wind was right, they would go up there and reel out a kite.

“Doesn’t look too promising.” His father, hand on door, glanced at the dark clouds bunching over the summit, and got out.

And still the music poured from the living room. His mother had hung on to the piano after she stopped singing. She was a first-rate pianist from her family’s point of view, but she was never going to sing again.

“I do hope Grandpa recovers,” Peter said to his father over the car roof. “Poor Mummy sounds seriously tense.”

“Go and talk to Ros,” said his father in a tender voice and went to put away his camera.

In the kitchen, Rosalind stirred a pot. Peter crept towards the stove. On the antique oak table where his mother’s pots had rested and burned circles, there were marks left with a blunt knife that mimicked his grandfather’s face.

But she heard him and spun around, and in a Monty Python voice said: “And that, my liege, is how we know the earth to be banana-shaped.” She licked the wooden spoon and made a musketeer’s lunge at his chest. He parried the spoon, seized her about the waist.

“Has Mummy told you? I have a Holy Grail to whit to woo, too.” She pulled away, smoothed back a stubborn blonde curl, and said, very seriously: “I’m going to become a gourmet chef.”

“Of course you are.”

Being at home, Rosalind was first in line in the epic food battle with their mother.

“Happy birthday, Bedevere,” giving him an asparagus-scented kiss.

From next door came their mother’s staccato rendering of the Goldberg Variations. Her voice might have gone, but her music was unstoppable.

“She’s bought you a present you won’t forget,” Rosalind teased, with the same inflexion as their father.

“What is it?”

“Not exactly something you can take back to school with you.”

“Have you heard from Camilla?”

“Yes,” slyly. “She sent you a message.”

“Well?”

“She wants to invite you to a party with Luke.”

“Luke?”

She wiggled her index finger in a way calculated to irritate. “Her BOYFRIEND.”

“Peter!”

Peter hadn’t heard the music stop. His mother wore a long saffron dress, a hand-me-down from one of his nannies, and her man’s watch, always slipping on her thin wrist.

“How long have you been here?” looking with a puzzled expression at the watch. Peter had given up asking why she insisted on wearing it. Never for a day had it kept the right time.

“Only a minute.”

They kissed. He put his hand on her shoulder and she tensed, drawing back to look at him. “Happy birthday, darling,” she said a little sadly, the same regretful tone as his father. She smelled of the French perfume that she always put on for special occasions, and he wondered for one ghastly moment if she had invited Leadley’s parents to lunch.

“I just hope it doesn’t rain, that’s all. What do you think, Rodney?” She placed all her faith in picnics.

He had just come into the room. “I don’t think it’ll rain,” and turned his inattention to the window. Next second, the heavens opened.

They had Rosalind’s vichyssoise in the dining room, then an asparagus quiche. His mother had chosen his favourite food, spoiling him, and he drank too much red wine.

He felt his father watching. He was aware of a quiet unrest in him and, when he thought about it afterwards, a premonition of something final.

The rain went on until they were eating strawberries and then the sun came out.

“Darling,” said his mother, rather nervous, as if testing a blade. “Can I show you something?”

“Mummy, the cake! Don’t forget the cake’s in the oven,” Rosalind said.

“Oh, God.”

His mother went into the kitchen and moments later he heard her going upstairs. When she came back she was clutching a photograph album he had never seen before. She sat beside him at the table and opened it: calf-bound, blue, full of images stuck down with white triangles, all of an odd-looking boy. Holding a cricket bat in a communal garden. Leaning from a pram. In christening robes.

“Look at those eyes – huge – always watering.”

He yawned. Why was she doing this?

From somewhere up in the house came a yap.

She moved her chair closer. Turning the wide pages, she told Peter that the boy was him. A fearer of dragons who had to ask their permission to get up in the mornings. The sun wasn’t yet hot enough for her face to be trickling with sweat. Some sort of expectation was making her nervous.

She went on speaking, but in a voice he hadn’t heard before. What she was telling him was beyond the furl of his understanding. Peter found the images far from reassuring. This was not a person he recognised, the boy with huge eyes. And why had his mother hidden this album all these years? He felt intruded on.

“Mummy!” he protested, and struggled against his mother’s arm around his shoulders. It was probably the cake making her morbid. She hated to cook, and had spent the whole morning preparing it.

“Wait.” In the same strange, needy tone she told him that he had been born one tea-time during a cold summer shortly before the Berlin Wall went up.

Pretending to look at the album, Peter studied the watch almost at her elbow. Even allowing for a spectacular margin of error, his train didn’t leave for another three hours. “You ought to get a new watch,” he said.

“I’m quite happy with this one, thank you.”

“Who’s that?” He craned forward, interested for the first time.

“That’s me in the Wigmore Hall, the year I went to Leipzig.”

She had trained as a singer in Manchester and was poised for a career with the BBC when something happened, Peter wasn’t sure what. The photograph showed a frizzy-haired young woman, firm shoulders in a long piqué dress, singing with an expression that she had lost.

In an otherwise crotchety cosmology, his mother had certain areas of tolerance. Unusual for one of her generation, she had a soft spot for Germans. The reminder of Leipzig gave her a second wind.

“Do you know what they called the Wigmore Hall before the First World War?” she went on tenaciously. “The Bechstein Hall. It was founded by Germans for German musicians.” She made a finger-crossing gesture. “That’s how close we used to be. Anglo- Saxons! I don’t care what Grandpa says. For centuries, the Germans have been England’s natural allies in Europe.”

“And didn’t the Connaught used to be the Coburg? And didn’t America very nearly choose German as its official language?” said his father helpfully, a hand burrowing under his cravat.

She exchanged a grateful glance, but it was Peter she had to convince. “You simply cannot imagine the Germanophobia,” she said, her enthusiasm shifting from the album to encompass in one bound a nation. “Even in the ’20s, Schubert Lieder, when sung in London, were sung in French.” She touched his arm. “And to think that we owe them our Royal Family, our religion, to say nothing of our music.”

“Come on, Peter.” The conversation was boring Rosalind. “Let’s play Scrabble.” And tugged at his hand, eyes plaintive under the stubborn curls.

Another yap.

“Why don’t we go for a walk?” Flustered, his mother brushed a lock of hair from his temples in the way that used to infuriate him as a boy. “And then you can have your present.”

“I’m not going for a walk,” said Peter.

“No, he’s coming with me,” piped up Rosalind.

“Rosalind!” From the end of the table, their father’s tone categorical in a way that Peter hadn’t often heard.

“Dear, maybe you could begin the washing-up.”

“Peter never does the washing-up,” Rosalind complained, spitting a strawberry onto her palm. “Ever.”

Rodney looked at Peter. “I think you should go. Do this for me.” And to his wife: “Henrietta. I really think. Now.”

Peter burst out: “What’s going on? It’s something about you, isn’t it? You’re having an affair. You’re getting divorced. You’re ill. Does Rosalind know?”

“I’m not ill. No affair. Just go for a walk. Go with your mother.”

Often at night when he couldn’t sleep Peter sifted his English childhood, beginning with the dragons under his bed and proceeding to the walk along the ox-drive and his mother’s revelation. A life-altering secret smelling of blackberry bushes after rain and causing a beating in his blood as if a large bird was taking off in the burrow of his chest.

In his memory, they climbed towards a summit fuzzy with rain. Towards the wreckage of the aeroplane and a body never discovered, just an iridescent slick for the Nadder mayflies to hatch on. But the sun, as it happened, was shining.

When they got to the top, she applied lipstick and adjusted her scarf, buttoning every single button of her coat.

“It’s turning into a lovely afternoon, but so chilly. Are you covered up? Look at that open neck of yours. Why didn’t you bring your scarf? I hope you don’t run around St Cross like that.”

A flint road led like vertebrae over the cornfields. She had been stumbling along it for five minutes when she stopped, already breathless.

“As you so often point out, I do have a knack for filing away things I prefer not to think about.” She fixed her watery green eyes on the sky. Her words flat and giving the impression she had rehearsed them. “You could describe it as a blockage of some kind. Or an inability to grapple with ‘personal issues’, as Rodney calls them. But I’m starting to talk about myself, and you need to know about Peter.”

She’s speaking of me as if I’m not here, he thought. Is she going nutty like her father? He yielded to an irritable blankness: “What do I need to know?”

“Not you, my love, not you,” she murmured. She rotated the watch on her wrist in a purposeless way and said: “Rodney’s not your father.”

Peter was aware of a bird’s shadow on the damp grass and something tearing inside.

“Your father’s someone else.”

“You mean I’m adopted?” he heard himself say.

“No, no, I’m your mother. In every other sense Rodney is your father. We met when you were six months old. Here, let’s sit down. I can say it better sitting down.”

They found a patch of grass where she began to explain that Peter’s father was not the affable and diffident Englishman to whom she had been married for 15 years, but an East German political prisoner whom she had known for hardly a day.