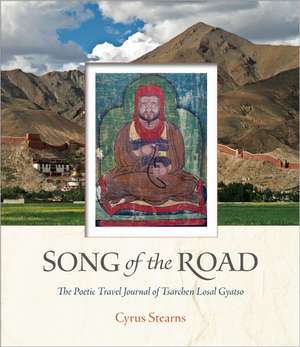

Song of the Road: The Poetic Travel Journal of Tsarchen Losal Gyatso

Autor Tsarchen Losal Gyatso Traducere de Cyrus Stearnsen Limba Engleză Hardback – 18 mar 2013

Like the Japanese master Basho's famous "Narrow Road to the Interior," written 150 years later, Tsarchen's travelogue contains a mixture of luminous prose and verse, rich with allusions. Traveling on horseback with a band of companions, Tsarchen visited some of the most renowned holy sites of the Tsang region, incluing Jonang, Tropu, Ngor, Shalu, and Gyantse. In his introduction and copious notes, Cyrus Stearns unearths the layers of meaning concealed in the text, excavating the history, legends, and lore associated with people and places encountered on the pilgrimage, revealing the spiritual as well as geographical topography of Tsarchen's journey.

Preț: 111.28 lei

Preț vechi: 133.06 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.29€ • 22.77$ • 17.75£

21.29€ • 22.77$ • 17.75£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-04 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781614290551

ISBN-10: 1614290555

Pagini: 173

Dimensiuni: 169 x 197 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Wisdom Publications (MA)

ISBN-10: 1614290555

Pagini: 173

Dimensiuni: 169 x 197 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Wisdom Publications (MA)

Cuprins

Preface

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Notes to the Introduction

Maps of Tsarchen’s Route

Celebration of the Cuckoo: My Autobiographical Song of the Road

by Tsarchen Losal Gyatso

Notes to the Translation

Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Notes to the Introduction

Maps of Tsarchen’s Route

Celebration of the Cuckoo: My Autobiographical Song of the Road

by Tsarchen Losal Gyatso

Notes to the Translation

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“Over the history of Tibetan Buddhism, travel across mountain and plain has long provided an occasion for profound reflections on more spiritual paths. Such reflections abound in Song of the Road. Readers of both English and Tibetan owe a great debt to the renowned translator Cyrus Stearns for bringing this almost forgotten work to the audience it so richly deserves.”—Donald Lopez, Chair, Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Michigan

“Cyrus Stearns's Song of the Road is a rare gem shining light on the life of the remarkable Tibetan master Tsarchen Losal Gyatso. This beautiful rendering of Tsarchen's autobiography captures, with such freshness, the immediacy and profound insight that characterize the Tibetan master's spiritual journey.”—Thupten Jinpa, Institute of Tibetan Classics

Notă biografică

Cyrus Stearns has been a student of Tibetan language, literature, and religion since 1973, when he began studying with the great Tibetan polymath, Dezhung Rinpoche (1906–87), and serving as his principal translator. In 1985 Cyrus was the leader of the Smithsonian Institutes Associates Tour to Tibet and China, one of the first groups allowed into Tibet after many years of travel restriction by the Chinese government, and he has lived in Asia eight years all together. Since receiving a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from the University of Washington in 1996, he has established himself as one of the most admired translators of Tibetan literature today. His numerous books include Taking the Result As the Path, Hermit of Go Cliffs, and King of the Empty Plain. He is currently a fellow at the Tsadra Foundation and a translator for the Library of Tibetan Classics. He lives in the woods on Whidbey Island, north of Seattle, Washington.

Extras

From near the opening of the text.

So. We began to travel at the pace of mendicants. During the fifth moon of the Pig Year the fresh grass had changed the landscape to a gentle green as if anointed with new emeralds. All the rivers and streams were fully swollen, like a sea of sapphires suddenly welling up, beautiful with garlands of waves whose white foamy smiles laughed in a hundred directions. It was time for the good festival of spring, so people were acting quite joyful and passionate, moving about with ballads and sounds of laughter filling by turns all the mountains and valleys.

With the messengers of invitation, there were about fifteen of us, teacher and students all in the prime of life, not too old or too young, wearing only the saffron victory banner of dress befitting ordained persons. Symbolizing emphatic, deliberate renunciation, we each carried a little tent of white cotton, like the shattered shard of a glacial mountain; a white rattan staff, like a tent pole of conch shell; a small meditation cushion; a square rug with untrimmed edges; a pouch and a three-cornered sack, as if woven of rubies and lotus roots; and a special volume of the profound oral transmission, with which to grace fortunate people. My pace on foot would have been too slow, so I rode a dependable fine gray horse that could handle the usual saddle, bridle, and so on. In keeping with the large summer cloak the Sage allowed, for protection from the rain we wore cloaks of whole serge seemingly bordered with lapis lazuli.

We set out from Tupten Gepel Monastery in Mangkar and rested a little at my family home. In the assembly hall of the palace of Namgyal Taktsé in upper Dar we completed the consecration of a stupa and held a celebration. Our gradual departure was like this:

The exquisite beauty

of the glorious swan king,

avian lord surrounded by ten

million ruddy sheldrakes,

departing from the shore

of a great enchanting lake,

is like the sky laced with red

dust of vermilion.

So, too, for the great benefit

of the doctrine and living beings,

a mendicant yogin swiftly departed

with a circle of saffron-clad students,

setting off for the wide herbal lands

in the region of Ü.

Seeing him, fortunate

young people expressed

various hopes and wishes,

thinking, “May I also be guided

in the footsteps of one like this,

whose way is happy in this life

and will be pleasant in the next.”

***

That night, not far away in a village called Döndrup Ling, there was a dense grove of trees with an open area where we pitched our tents like a garland of white clouds arranged in a row. The stages of the Dharma liturgy roared like thunder. As we sat enjoying a drink of fine, strong, yet fragrant Chinese tea cascading like a summer river, the honorable Dharma lord at that monastery invited several of us, teacher and students, and held a lavish welcoming reception. The steward, and monks I knew from before, also served tea and so forth, so an auspicious combination of good things occurred at the beginning.

Before that, rain had been a bit scarce, but after that, when we teacher and students began to engage in the yoga of two stages during our individual evening sessions, rain clouds softly clustered from valleys in every direction. When great sheets of rain fell with a deep rumble of thunder, the grains were fully nurtured and the minds of people were nourished with joy and happiness.

When that bum set out

upon the path, as a good

sign of the compassion

of his crown ornament,

the venerable lord Khaupa,

a thousand light rays shone,

and from the joyous musical

drama of the nagas of the sea,

new rain clouds clustered

in all directions.

Thunder chuckled

from the wombs of clouds.

Heralded by fresh garlands

of lightning, here today

a great rain of wish-fulfilling

perfume fell.

Just like lotuses opened

by the young sun, the bright

smiles of crops and plants

flickered in the ten directions.

And people sang songs,

gleefully buzzing

like honey-crazed bees.

Notes:

Pig Year (phag gi lo): Basically corresponding to the last nine or ten months of the Western calendar year of 1539 and the first two or three months of 1540.

the Sage (Thub pa): The historical Buddha Sakyamuni (ca. 566 B.C.–ca. 486 B.C.).

Tupten Gepel Monastery in Mangkar (Mang mkhar Thub bstan dge ’phel dgon pa): Tsarchen had become abbot of Tupten Gepel Monastery high in the Mangkar Valley in 1534. He mostly stayed there until he left for Ü in 1539. The years at Tupten Gepel were spent practicing meditation, teaching, composing works such as the biographies of lord Doringpa and Dakchen Lodrö Gyaltsen, and visiting other areas in central and west-central Tibet to give initiations, guiding instructions, and textual transmissions. See Ngawang Losang Gyatso, Sunlight of the Doctrine of the Explication for Disciples, 510, 519.

my family home: Tsarchen’s ancestral home was at Mushong in the lower part of the Mangkar Valley.

the palace of Namgyal Taktsé in upper Dar (’Dar stod Rnam rgyal stag rtse’i pho brang): This palace, where Tsarchen often stayed in later years, was close to his birthplace of Mushong, but up on a mountainside at the mouth of the Mangkar Valley. It was the fortress of the ruler of the Dar region, Darpa Rinchen Palsang (’Dar pa Rin chen dpal bzang), a patron of Tsarchen’s activities who wrote a beautiful biographical supplication (rnam thar gsol ’debs) to him after the master’s death. The Fifth Dalai Lama later used Rinchen Palsang’s work as a central narrative thread in his biography of Tsarchen.

yoga of two stages: The main two phases of the Vajrayana practice of deity yoga. The creation stage involves visualization of the diety and the completion stage is usually composed of meditation on subtle channels, winds, and drops, and resting the mind in lucid emptiness.

venerable lord Khaupa (Rje btsun Kha’u pa): Kunpang Doringpa, Tsarchen’s most important teacher, who lived at the hermitage of Khau Drakzong

So. We began to travel at the pace of mendicants. During the fifth moon of the Pig Year the fresh grass had changed the landscape to a gentle green as if anointed with new emeralds. All the rivers and streams were fully swollen, like a sea of sapphires suddenly welling up, beautiful with garlands of waves whose white foamy smiles laughed in a hundred directions. It was time for the good festival of spring, so people were acting quite joyful and passionate, moving about with ballads and sounds of laughter filling by turns all the mountains and valleys.

With the messengers of invitation, there were about fifteen of us, teacher and students all in the prime of life, not too old or too young, wearing only the saffron victory banner of dress befitting ordained persons. Symbolizing emphatic, deliberate renunciation, we each carried a little tent of white cotton, like the shattered shard of a glacial mountain; a white rattan staff, like a tent pole of conch shell; a small meditation cushion; a square rug with untrimmed edges; a pouch and a three-cornered sack, as if woven of rubies and lotus roots; and a special volume of the profound oral transmission, with which to grace fortunate people. My pace on foot would have been too slow, so I rode a dependable fine gray horse that could handle the usual saddle, bridle, and so on. In keeping with the large summer cloak the Sage allowed, for protection from the rain we wore cloaks of whole serge seemingly bordered with lapis lazuli.

We set out from Tupten Gepel Monastery in Mangkar and rested a little at my family home. In the assembly hall of the palace of Namgyal Taktsé in upper Dar we completed the consecration of a stupa and held a celebration. Our gradual departure was like this:

The exquisite beauty

of the glorious swan king,

avian lord surrounded by ten

million ruddy sheldrakes,

departing from the shore

of a great enchanting lake,

is like the sky laced with red

dust of vermilion.

So, too, for the great benefit

of the doctrine and living beings,

a mendicant yogin swiftly departed

with a circle of saffron-clad students,

setting off for the wide herbal lands

in the region of Ü.

Seeing him, fortunate

young people expressed

various hopes and wishes,

thinking, “May I also be guided

in the footsteps of one like this,

whose way is happy in this life

and will be pleasant in the next.”

***

That night, not far away in a village called Döndrup Ling, there was a dense grove of trees with an open area where we pitched our tents like a garland of white clouds arranged in a row. The stages of the Dharma liturgy roared like thunder. As we sat enjoying a drink of fine, strong, yet fragrant Chinese tea cascading like a summer river, the honorable Dharma lord at that monastery invited several of us, teacher and students, and held a lavish welcoming reception. The steward, and monks I knew from before, also served tea and so forth, so an auspicious combination of good things occurred at the beginning.

Before that, rain had been a bit scarce, but after that, when we teacher and students began to engage in the yoga of two stages during our individual evening sessions, rain clouds softly clustered from valleys in every direction. When great sheets of rain fell with a deep rumble of thunder, the grains were fully nurtured and the minds of people were nourished with joy and happiness.

When that bum set out

upon the path, as a good

sign of the compassion

of his crown ornament,

the venerable lord Khaupa,

a thousand light rays shone,

and from the joyous musical

drama of the nagas of the sea,

new rain clouds clustered

in all directions.

Thunder chuckled

from the wombs of clouds.

Heralded by fresh garlands

of lightning, here today

a great rain of wish-fulfilling

perfume fell.

Just like lotuses opened

by the young sun, the bright

smiles of crops and plants

flickered in the ten directions.

And people sang songs,

gleefully buzzing

like honey-crazed bees.

Notes:

Pig Year (phag gi lo): Basically corresponding to the last nine or ten months of the Western calendar year of 1539 and the first two or three months of 1540.

the Sage (Thub pa): The historical Buddha Sakyamuni (ca. 566 B.C.–ca. 486 B.C.).

Tupten Gepel Monastery in Mangkar (Mang mkhar Thub bstan dge ’phel dgon pa): Tsarchen had become abbot of Tupten Gepel Monastery high in the Mangkar Valley in 1534. He mostly stayed there until he left for Ü in 1539. The years at Tupten Gepel were spent practicing meditation, teaching, composing works such as the biographies of lord Doringpa and Dakchen Lodrö Gyaltsen, and visiting other areas in central and west-central Tibet to give initiations, guiding instructions, and textual transmissions. See Ngawang Losang Gyatso, Sunlight of the Doctrine of the Explication for Disciples, 510, 519.

my family home: Tsarchen’s ancestral home was at Mushong in the lower part of the Mangkar Valley.

the palace of Namgyal Taktsé in upper Dar (’Dar stod Rnam rgyal stag rtse’i pho brang): This palace, where Tsarchen often stayed in later years, was close to his birthplace of Mushong, but up on a mountainside at the mouth of the Mangkar Valley. It was the fortress of the ruler of the Dar region, Darpa Rinchen Palsang (’Dar pa Rin chen dpal bzang), a patron of Tsarchen’s activities who wrote a beautiful biographical supplication (rnam thar gsol ’debs) to him after the master’s death. The Fifth Dalai Lama later used Rinchen Palsang’s work as a central narrative thread in his biography of Tsarchen.

yoga of two stages: The main two phases of the Vajrayana practice of deity yoga. The creation stage involves visualization of the diety and the completion stage is usually composed of meditation on subtle channels, winds, and drops, and resting the mind in lucid emptiness.

venerable lord Khaupa (Rje btsun Kha’u pa): Kunpang Doringpa, Tsarchen’s most important teacher, who lived at the hermitage of Khau Drakzong

Descriere

In Song of the Road, Tsarchen Losal Gyatso (1502-66), a tantric master of the Sakya tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, weaves ecstatic poetry, song, and accounts of visionary experiences into a record of pilgrimage to central Tibet. Translated for the first time here, Tsarchen’s work, a favorite of the Fifth Dalai Lama, brims with striking descriptions of encounters with the divine as well as lyrical portraits of Tibetan landscape. The literary flights of Song of the Road are anchored by Tsarchen’s candid observations on the social and political climate of his day, including a rare example in Tibetan literature of open critique of religious power.

In his introduction and copious notes, Cyrus Stearns unearths the layers of meaning concealed in the text, excavating the history, legends, and lore associated with people and places encountered on the pilgrimage, revealing the spiritual as well as geographical topography of Tsarchen's journey.

In his introduction and copious notes, Cyrus Stearns unearths the layers of meaning concealed in the text, excavating the history, legends, and lore associated with people and places encountered on the pilgrimage, revealing the spiritual as well as geographical topography of Tsarchen's journey.