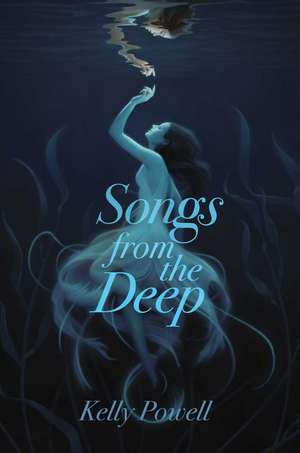

Songs from the Deep

Autor Kelly Powellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 9 dec 2020 – vârsta de la 13 ani

The sea holds many secrets.

Moira Alexander has always been fascinated by the deadly sirens who lurk along the shores of her island town. Even though their haunting songs can lure anyone to a swift and watery grave, she gets as close to them as she can, playing her violin on the edge of the enchanted sea. When a young boy is found dead on the beach, the islanders assume that he’s one of the sirens’ victims. Moira isn’t so sure.

Certain that someone has framed the boy’s death as a siren attack, Moira convinces her childhood friend, the lighthouse keeper Jude Osric, to help her find the real killer, rekindling their friendship in the process. With townspeople itching to hunt the sirens down, and their own secrets threatening to unravel their fragile new alliance, Moira and Jude must race against time to stop the killer before it’s too late—for humans and sirens alike.

Preț: 49.40 lei

Preț vechi: 57.98 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.45€ • 9.89$ • 7.87£

9.45€ • 9.89$ • 7.87£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534438095

ISBN-10: 1534438092

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: metallic stock, 6 colors, spot gloss uv

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

ISBN-10: 1534438092

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: metallic stock, 6 colors, spot gloss uv

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Colecția Margaret K. McElderry Books

Notă biografică

Kelly Powell has a bachelor’s degree in history and book and media studies from the University of Toronto. She currently lives in Ontario. She is the author of Songs from the Deep and Magic Dark and Strange. Visit her online at PowellKelly.com or on Twitter @KellyCPowell.

Extras

Chapter OneCHAPTER ONE

![]()

THERE ARE THREE SIRENS on the beach today.

I watch them, rosining my bow slowly as I do. The tide comes in, restless and white-capped, pushing at the shoreline. The cliff grass pricks at the thin cotton of my dress as I stand, keeping my eyes trained on the beach below.

They are distant and impassive, marble statues staring out to sea.

Movement is rarely what catches their attention. Sound is how they hunt, what they wait for. Any noise is tenfold more interesting to them than a wave of fingers or shuffle of feet.

I slide my bow across the violin in an open note. The song becomes slower, softer, as I dip into a lower pitch. When I quicken my pace, the violin’s sound vibrates through the air, and I feel it humming in my chest, in the soles of my feet. The music is sharp against the noonday stillness, the only sound in my ears.

It is a cool afternoon at that. My breath mists in front of me, my fingers holding stiff to the bow’s polished wood. The sirens do not seem to mind the chill. They are folded between a bramble of large rocks, their backs to me—long stretches of pale white skin, dark tangled hair—and one of them leans over, resting her head upon the shoulder of another.

I play by the cliff’s edge, allowing music to tumble over rocks and into sea. It’s the closest I dare play to the beach, as the melodies may well turn siren ears and eyes in my direction. Nothing wrong with a bit of danger though, when it polishes the notes. I play best on days like this, with the sirens near, before the unending sea.

Perhaps they talk to one another. Yet it’s the songs they sing that lure anyone within earshot and without protection. I’ve seen those rescued taken to the hospital: bloodied from teeth and claws, delirious, all too keen to return to the sea, to the creatures in the depths below. Terrible business for the tourists in the end, and still they come. Every summer. For the scenery or for the sirens, perhaps hoping this year shall be the year when Twillengyle Council finally lifts the ban on siren hunting.

That is the year I dread.

I curl my fingers tighter around the violin to get some life back in them. A few minutes more and I’ll pack up. Feels lonely, playing for only three sirens, when I’ve seen groups of ten or fifteen together on the sand at one time. The wind picks up, biting at my cheeks until I know they’re rosy with cold, and the sea’s string of whitecaps blacken the rocks with their spray. I skip from one tune to the next in an attempt to find a rhythm.

Each note flies off on the wind—toward sirens who do not even turn an ear in acknowledgment. I touch bow to strings a little more firmly.

When the music falters, I stop. A breeze catches the hem of my dress, flicking it this way and that, while I place my violin into its case. It’s a battered little thing, black leather faded and scuffed. My father gave it to me years ago, with my initials stamped along the side.

M. A.

The music of my heart.

Not a very good turn of phrase, as his heart ceased beating only two weeks after. Or not very good music, I think, loosening the hair of my bow before setting it inside.

I gather up the violin case and take one last glance down the cliff. The sirens have barely moved. One has twisted around slightly, so I can see the knife edge of her cheekbone. Not enough to see her eyes properly. Before, I have—at the right angle and with enough light—and their wide, dark eyes seem to mirror the deepest parts of the sea.

It was my father who first brought me to them, taught me how to clean salt from violin strings, where to watch sirens without being seen, how to protect myself with cold iron and charms. He showed me an island smeared in blood, and I fell in love with it.

On those days, when the sky was still pink with dawn, my father told me the island’s folktales. He brought me to the beach and spoke of the creatures the sea sheltered, of the magic that dwelt on Twillengyle’s shores. And when the moon shone overhead, full and bright as a coin, ghost stories were told—the souls of those killed by sirens said to wander the cliffs evermore.

But today is windblown and damp, fog misting around me, clinging to my dress. These are the days for ballads and sorrow, remembrances of widows standing in my place, waiting on the cliffs, not knowing their husbands had already been swept out to sea. The beach gives way to rocks that rise above the waves like chipped grave markers. It’s scenery the tourists adore: dark-green swaths of moss and red-brown grass, the sheer face of the crag stained salt white.

I don’t know whether the sirens watch me as I leave, or if the cliff’s edge holds a pull of its own. Whichever way, my heart feels leaden as I head for home.

But I have long realized a piece of it will always belong to the sea.

THERE ARE THREE SIRENS on the beach today.

I watch them, rosining my bow slowly as I do. The tide comes in, restless and white-capped, pushing at the shoreline. The cliff grass pricks at the thin cotton of my dress as I stand, keeping my eyes trained on the beach below.

They are distant and impassive, marble statues staring out to sea.

Movement is rarely what catches their attention. Sound is how they hunt, what they wait for. Any noise is tenfold more interesting to them than a wave of fingers or shuffle of feet.

I slide my bow across the violin in an open note. The song becomes slower, softer, as I dip into a lower pitch. When I quicken my pace, the violin’s sound vibrates through the air, and I feel it humming in my chest, in the soles of my feet. The music is sharp against the noonday stillness, the only sound in my ears.

It is a cool afternoon at that. My breath mists in front of me, my fingers holding stiff to the bow’s polished wood. The sirens do not seem to mind the chill. They are folded between a bramble of large rocks, their backs to me—long stretches of pale white skin, dark tangled hair—and one of them leans over, resting her head upon the shoulder of another.

I play by the cliff’s edge, allowing music to tumble over rocks and into sea. It’s the closest I dare play to the beach, as the melodies may well turn siren ears and eyes in my direction. Nothing wrong with a bit of danger though, when it polishes the notes. I play best on days like this, with the sirens near, before the unending sea.

Perhaps they talk to one another. Yet it’s the songs they sing that lure anyone within earshot and without protection. I’ve seen those rescued taken to the hospital: bloodied from teeth and claws, delirious, all too keen to return to the sea, to the creatures in the depths below. Terrible business for the tourists in the end, and still they come. Every summer. For the scenery or for the sirens, perhaps hoping this year shall be the year when Twillengyle Council finally lifts the ban on siren hunting.

That is the year I dread.

I curl my fingers tighter around the violin to get some life back in them. A few minutes more and I’ll pack up. Feels lonely, playing for only three sirens, when I’ve seen groups of ten or fifteen together on the sand at one time. The wind picks up, biting at my cheeks until I know they’re rosy with cold, and the sea’s string of whitecaps blacken the rocks with their spray. I skip from one tune to the next in an attempt to find a rhythm.

Each note flies off on the wind—toward sirens who do not even turn an ear in acknowledgment. I touch bow to strings a little more firmly.

When the music falters, I stop. A breeze catches the hem of my dress, flicking it this way and that, while I place my violin into its case. It’s a battered little thing, black leather faded and scuffed. My father gave it to me years ago, with my initials stamped along the side.

M. A.

The music of my heart.

Not a very good turn of phrase, as his heart ceased beating only two weeks after. Or not very good music, I think, loosening the hair of my bow before setting it inside.

I gather up the violin case and take one last glance down the cliff. The sirens have barely moved. One has twisted around slightly, so I can see the knife edge of her cheekbone. Not enough to see her eyes properly. Before, I have—at the right angle and with enough light—and their wide, dark eyes seem to mirror the deepest parts of the sea.

It was my father who first brought me to them, taught me how to clean salt from violin strings, where to watch sirens without being seen, how to protect myself with cold iron and charms. He showed me an island smeared in blood, and I fell in love with it.

On those days, when the sky was still pink with dawn, my father told me the island’s folktales. He brought me to the beach and spoke of the creatures the sea sheltered, of the magic that dwelt on Twillengyle’s shores. And when the moon shone overhead, full and bright as a coin, ghost stories were told—the souls of those killed by sirens said to wander the cliffs evermore.

But today is windblown and damp, fog misting around me, clinging to my dress. These are the days for ballads and sorrow, remembrances of widows standing in my place, waiting on the cliffs, not knowing their husbands had already been swept out to sea. The beach gives way to rocks that rise above the waves like chipped grave markers. It’s scenery the tourists adore: dark-green swaths of moss and red-brown grass, the sheer face of the crag stained salt white.

I don’t know whether the sirens watch me as I leave, or if the cliff’s edge holds a pull of its own. Whichever way, my heart feels leaden as I head for home.

But I have long realized a piece of it will always belong to the sea.

Descriere

A girl searches for a killer on an island where deadly sirens lurk just beneath the waves in this atmospheric story.