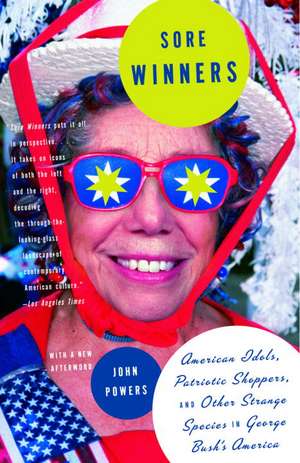

Sore Winners: American Idols, Patriotic Shoppers, and Other Strange Species in George Bush's America

Autor John Powersen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2005

In this wonderfully acerbic tour through our increasingly unhinged culture, John Powers takes on celebrities and evangelicals, pundits and politicians, making sense of the mess for the rest of us. He shows how we have come to equate consumerism with patriotism and Fox News with objective journalism, and how our culture has become more polarized than ever even as we all shop at the same exact big-box stores. Insightful, hilarious, and critical of both liberals and conservatives, this is one of the smartest and most enjoyable books on American culture in years.

Preț: 81.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 122

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.59€ • 16.32$ • 12.90£

15.59€ • 16.32$ • 12.90£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400076550

ISBN-10: 1400076552

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 160 x 209 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400076552

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 160 x 209 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

John Powers is the film critic at Vogue and Editor-at-Large of L.A. Weekly, where he writes a media-culture column. He is also critic-at-large for NPR's "Fresh Air with Terry Gross,” and has been an international correspondent for Gourmet. He lives in Pasadena, California. with his wife, Sandi Tan.

Extras

Chapter 1

The Six Faces of George W. Bush

Will the Real Slim Shady please stand up

Please stand up, Please stand up

–Eminem

On June 4, 2002, President George W. Bush held a diplomatic summit with Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and Palestinean Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas at a palace in Aqaba, a small coastal city best known for the Hollywood-fed myth that it had once been captured by Lawrence of Arabia. After the day's discussions, the leaders strolled together toward the world’s cameras, crossing a bridge built over a swimming pool. It was the kind of culminating image, fat with metaphor–the bridging of divided peoples, the President acting as a uniter–that the Bush White House likes to call “the money shot,” perhaps oblivious of its porn-world associations. The President’s advance team hadn’t just mapped out the leaders’ path, as earlier White House staffs might have done. They had asked the Jordanians to build a bridge over the pool so that Bush and the others could walk over water on their way to the banks of cameras. When the first bridge proved too narrow to accommodate the men side by side, the Bush people had it torn down and a new one built that was wide enough. They were well aware that this visual iconography would matter far more to American TV viewers than anything the President would actually say.

Ever since Parson Weems cooked up the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, our presidents have come robed in mythology, much of it consciously crafted. In the 1920s, the founding father of American advertising, Edward L. Bernays, was asked to help Calvin Coolidge fight the perception that he was icy and remote. Bernays brought Al Jolson and a cohort of his fellow vaudevilleans to breakfast at the White House, an event that prompted the humanizing headline “President Nearly Laughs”–and opened the gate for events staged by media advisors (or pseudo-events, as Daniel Boorstin termed them). Just as advertising has grown more sophisticated in the last eighty years, so has presidential image making. If it was by serendipity that the musical Camelot opened less than one month after John F. Kennedy was elected president, it was his widow Jackie who, in her sole interview after his assassination, planted the idea of America happy-ever-aftering in that fantasy of JFK’s White House.

Spooked by the power of Kennedy’s dashing image, Richard Nixon put himself in the hands of media advisors in 1968, and, as Joe McGinnis famously chronicled in The Selling of the President, they pulled off an extraordinary feat. Tricky Dick was repackaged as The New Nixon, a changed man whose painfully forced smile was something a divided nation could believe in. Small wonder that the Nixon team’s techniques were studied and refined by Ronald Reagan, who invested every manipulated scenario with enormous charisma, and Bill Clinton, who knew all the tricks in The Gipper’s playbook–it wasn’t for nothing that the boy from racy Hot Springs, Arkansas, sold himself as The Man from Hope.

The current White House has scrutinized these precedents and more. No president has controlled his PR more tightly than Bush, who watched aghast as his father lost control of his persona–going from sturdy Cold Warrior to vomiting babbler–and plummeted from 89 percent approval ratings in the summer of 1991 to 37.7 percent of the vote in the 1992 election. Conscious that presidents, like all consumer products, rise and fall on their image, his staff treats each event with the lavish precision of a Michael Mann movie. They’d never let him go on TV wearing a cardigan, as Jimmy Carter did in what’s remembered as his ruinous Malaise Speech. He didn’t actually use the word “malaise,” but such is the power of myth. Bush’s handlers know that they’re courting trouble whenever they put him out there on his own. That’s why he held only eleven solo press conferences in the first three years of his presidency (in the same period, his dad held more than sixty). Like Ben Affleck, who can’t hold the screen all by himself, their man needs to be propped up with crack production design. When he spoke about the scandals at Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen, Merrill Lynch, Adelphia, Dynegy, Rite Aid, and Global Crossing, he stood before a backdrop with the words “Corporate Responsibility” printed again and again as a kind of corroborative wallpaper; when he addressed the nation from Ellis Island on September 11, 2002, an advance team brought in special banks of lights so that the Statue of Liberty would be suitably commanding against the night sky, its pale radiance neatly echoing the blue of the President’s necktie; when he served up a major speech on national security, he was carefully situated before Mount Rushmore, as if auditioning for his spot on the squad. And the White House does this sort of thing almost every day. No less a figure than Michael Deaver, who designed Reagan’s PR blitzes, told The News Hour with Jim Lehrer that the Bush team has taken packaging a president to a startling new level. He called their work “absolutely brilliant,” while conceding that including Bush’s head with the Mount Rushmore quartet may have been going a bit “too far.”*

**The image-building work extends to fiddling with documents that might reflect badly on the president. After Bush’s May 1, 2003, "Mission Accomplished” speech aboard the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln, the White House website ran a headline, “President Bush Announces Combat Operations in Iraq Have Ended.." But as TheMemoryHole.com revealed, once the insurrection proved stronger than expected, somebody went back and added the word “Major” before “Combat.”

Predictably, such transparent but skillful shaping of the President’s image horrifies those who think that Bush is a latter-day Wizard of Oz (conveniently forgetting that Clinton did the same thing, albeit less blatantly). They point with glee to ex—Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill’s remark that, in cabinet meetings, the President was like a blind man in a room full of deaf people. They wonder if Bush really calls the shots or whether he’s a hologram created by Dick Cheney and Karl Rove. They decry the abyss dividing the way the President is presented and what his administration is actually up to behind closed doors: Did he and Cheney privately joke about that big Halliburton contract in Iraq? Critics want to probe behind the myth and learn exactly who did what and when and why. They want to get “inside” the “real” George Bush.

Why? Much of any presidency’s meaning lies precisely in its constantly changing overlay of imagery, propaganda, rumor, and journalistic blather. To strip them away in search of the “real” president is like trying to find the real onion by peeling away the layers. This is especially true of George W. Bush, who, like John Kennedy four decades before him, has spawned an astonishing number of personas in a remarkably short time, many of them contradictory. Over the last four years we’ve had Bush as Regular Guy, Village Idiot, No-Nonsense CEO, Compassionate Conservative, latter-day Prince Hal, and, of course, Moby Dubya devouring any Democrat foolish enough to stray into his path. None of these myths is without its truth, and each has, at times, served the President’s purposes. What matters here is not so much George Bush the real man as the idea of “George Bush”–the images of the man that America has been peddled over the last four years.

#1: A Regular Guy

During the run-up to the 2002 congressional elections, Bush broke all records for the number of days a president spent campaigning for his party’s candidates. He seemed to be everywhere. Late one night on cable, supporters at a Republican rally explained why they liked him. Their reasons varied, to be sure (“He’s strong,” “He’s a real leader,” etc.), but were united by a common thread: The President was genuine, straightforward, a regular guy. Or as his advisor Karl Rove likes to put it, “He is who he is.”

There’s no denying that this is a potent tautology, identical to the one favored by no less a mensch than Popeye the Sailorman, but it does beg the larger question: Who is he? At first glance, one thing seems clear. He’s not a regular guy. In fact, Bush could almost be the archetype of the un-regular guy, the spoiled rich kid perpetually mocked by our culture from The Magnificent Ambersons’ unbearable Georgie to the high school snots in those 1980s John Hughes comedies. It’s worth recalling that “Junior” Bush comes not merely from privilege but long-standing privilege. On his mother’s side, he’s related both to the British royal family (he’s a distant cousin of Queen Elizabeth II) and to President Franklin Pierce; on the Bush side, he’s the grandson of U.S. Senator Prescott Bush, an old-school WASP of the Eastern Establishment, and, of course, the son of George H. W. Bush–Congressman, CIA boss, Nixon frontman at the Republican National Committee, Vice President, and Commander in Chief. Like his father, he attended Andover and Yale and then, for good measure, went to Harvard Business School. But his youth, which lasted until he was almost forty, was not exactly impressive. He was a lazy student (specializing in the Gentleman’s C), a tireless party animal with a DWI arrest in Maine, a lousy businessman, and a superb mama’s boy. Countless Americans of his generation followed a similar youthful path and wound up working for John Deere or standing in the unemployment line. They actually completed their military service, though; Dubya couldn’t be bothered. He ducked the Vietnam War by joining the Texas Air National Guard, jumping the queue to get in, and then, as we all now know, shortchanged his service with impunity: His dad was a congressman. Somehow, he wound up a rich man (estimated worth $9—$26 million) and President of the United States.

One might think such a background would have ordinary people fuming. Yet as Paul Fussell and others have so patiently noted, Americans don’t view class in the strict European way. Individuals are defined less by birth, which they can’t choose, than by personal style, which they can. In many ways, Bush does have the manner of a regular guy–his prodigal youth gives him an aura of rebellion against the hoity-toity ways of the elite. He enjoys sports and remains faithful, we’re told, to his wife. He likes folksy plain talk and dislikes people who put on airs. He doesn’t want to know all that much about current events. Even his onetime drinking troubles help establish his ordinary-guy bona fides: Everyone knows someone who’s had alcohol or drug

problems, and Americans admire those who fall and pick themselves up. A square during the sixties, when he was an Andover cheerleader and the chief Deke at Yale, he bristles at anything that smacks of bohemia or the counterculture. He is overt about his Christian faith, and in a country that’s ever more openly religious (39 percent of Americans claim to be born again), this does make him far more “regular” than most Democratic politicians, or even his own family. Where his father always came off as a faux Texan–“deep doo-doo” is not what littered the trail to the Alamo–Junior feels happiest in Texas, preferring the provincialism of its white oligarchy to the big-city ways back east, where people are uppity about his home state. Doubt his credentials, though, and he’ll instantly remind you that he went to Harvard and Yale. While Bush’s love for Texas is genuine–being “home” matters deeply to him–he’s politician enough to milk its symbolism as a political asset; hence his 1999 purchase of a ranch eight miles from the white-flight suburb of Crawford. Located amid one of the most reactionary enclaves in the nation, this sprawling homestead not only lets him escape the media’s prying eye but affords him chances to be photographed wearing cowboy boots and a belt buckle the size of a hubcap, manfully (and Reaganfully) cutting back brush. How many times in his life do you think he’s done this off-camera?*

*A lot of people work the Texas shtick. Although Molly Ivins went to Smith, got an M.A. from Columbia Journalism School, and was once a bureau chief for The New York Times, her own folksiness makes George W. Bush sound like George Plimpton.

It would be wrong to belabor the image of Bush as a weekend rancher, for that’s only a symptom of his real appeal. In a larger iconic sense, his public persona harks back to a vanishing yet still hardy ideal of white American masculinity, one embodied in today’s movies by Harrison Ford, who, rather like the President, is good at making wisecracks that don’t quite mask the surliness lying beneath. Like a less glamorous Jack Ryan or Indiana Jones, Bush comes across as a terse man of action whose pride is that he says what he means, means what he says, and if you don’t like it, too damn bad. The last president to court such an image was Harry Truman, who spent his final decades puffing up his reputation for straight shooting. Most regular guys can’t afford to adopt such attitude–unlike Dubya, they don’t have the connections to escape its consequences–but the fantasy appeals to them. That’s precisely why Bush has been sold as a self-confident straight-shooter by both his handlers and the conservative journalists who have crafted his myth. “George W. Bush doesn’t give a damn what you think of him,” wrote Tucker Carlson in a much-vaunted Talk profile back in 2000, ignoring all the ways this attitude might be insidious (and dishonest) in a man prepared to soft-pedal his right-wing ideology to momentarily woo swing voters. “That may be why you’ll vote for him for president.”

The Bush team tries to reinforce his virile image by stressing his physicality; perhaps he was a macho cheerleader. We’re told that he runs the mile in less than seven minutes (or did until he injured himself), ending the long national nightmare of Clinton’s jiggly pale thighs. We’re treated to displays like the tail-hook landing on the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln–his abbreviated time in the Air National Guard came in handy, after all–which demonstrated how dashing the President could be in a flight suit. Norman Mailer has suggested that Bush could have made “a world-class male model,” and though this wasn’t meant kindly, the old brawler was onto a truth: The President never seems looser than when he’s doing something purely physical. Bush was far more relaxed in that flight suit than he’d ever been in a business suit, let alone during any of his rare press conferences. In fact, the more you see him doing official business, the more you sense his tension at having to be presidential. It’s there in his peculiar stride across the White House Lawn, elbows out like a clichéd French pedestrian, palms facing apishly backward (an echo of those ears?). It’s there in the slightly clumsy way he whispers to his foreign guests as they stand before the media. It’s there in the narrowed eyes inherited from his father that greet any question he fears might contain a hidden fish hook.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Six Faces of George W. Bush

Will the Real Slim Shady please stand up

Please stand up, Please stand up

–Eminem

On June 4, 2002, President George W. Bush held a diplomatic summit with Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and Palestinean Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas at a palace in Aqaba, a small coastal city best known for the Hollywood-fed myth that it had once been captured by Lawrence of Arabia. After the day's discussions, the leaders strolled together toward the world’s cameras, crossing a bridge built over a swimming pool. It was the kind of culminating image, fat with metaphor–the bridging of divided peoples, the President acting as a uniter–that the Bush White House likes to call “the money shot,” perhaps oblivious of its porn-world associations. The President’s advance team hadn’t just mapped out the leaders’ path, as earlier White House staffs might have done. They had asked the Jordanians to build a bridge over the pool so that Bush and the others could walk over water on their way to the banks of cameras. When the first bridge proved too narrow to accommodate the men side by side, the Bush people had it torn down and a new one built that was wide enough. They were well aware that this visual iconography would matter far more to American TV viewers than anything the President would actually say.

Ever since Parson Weems cooked up the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, our presidents have come robed in mythology, much of it consciously crafted. In the 1920s, the founding father of American advertising, Edward L. Bernays, was asked to help Calvin Coolidge fight the perception that he was icy and remote. Bernays brought Al Jolson and a cohort of his fellow vaudevilleans to breakfast at the White House, an event that prompted the humanizing headline “President Nearly Laughs”–and opened the gate for events staged by media advisors (or pseudo-events, as Daniel Boorstin termed them). Just as advertising has grown more sophisticated in the last eighty years, so has presidential image making. If it was by serendipity that the musical Camelot opened less than one month after John F. Kennedy was elected president, it was his widow Jackie who, in her sole interview after his assassination, planted the idea of America happy-ever-aftering in that fantasy of JFK’s White House.

Spooked by the power of Kennedy’s dashing image, Richard Nixon put himself in the hands of media advisors in 1968, and, as Joe McGinnis famously chronicled in The Selling of the President, they pulled off an extraordinary feat. Tricky Dick was repackaged as The New Nixon, a changed man whose painfully forced smile was something a divided nation could believe in. Small wonder that the Nixon team’s techniques were studied and refined by Ronald Reagan, who invested every manipulated scenario with enormous charisma, and Bill Clinton, who knew all the tricks in The Gipper’s playbook–it wasn’t for nothing that the boy from racy Hot Springs, Arkansas, sold himself as The Man from Hope.

The current White House has scrutinized these precedents and more. No president has controlled his PR more tightly than Bush, who watched aghast as his father lost control of his persona–going from sturdy Cold Warrior to vomiting babbler–and plummeted from 89 percent approval ratings in the summer of 1991 to 37.7 percent of the vote in the 1992 election. Conscious that presidents, like all consumer products, rise and fall on their image, his staff treats each event with the lavish precision of a Michael Mann movie. They’d never let him go on TV wearing a cardigan, as Jimmy Carter did in what’s remembered as his ruinous Malaise Speech. He didn’t actually use the word “malaise,” but such is the power of myth. Bush’s handlers know that they’re courting trouble whenever they put him out there on his own. That’s why he held only eleven solo press conferences in the first three years of his presidency (in the same period, his dad held more than sixty). Like Ben Affleck, who can’t hold the screen all by himself, their man needs to be propped up with crack production design. When he spoke about the scandals at Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen, Merrill Lynch, Adelphia, Dynegy, Rite Aid, and Global Crossing, he stood before a backdrop with the words “Corporate Responsibility” printed again and again as a kind of corroborative wallpaper; when he addressed the nation from Ellis Island on September 11, 2002, an advance team brought in special banks of lights so that the Statue of Liberty would be suitably commanding against the night sky, its pale radiance neatly echoing the blue of the President’s necktie; when he served up a major speech on national security, he was carefully situated before Mount Rushmore, as if auditioning for his spot on the squad. And the White House does this sort of thing almost every day. No less a figure than Michael Deaver, who designed Reagan’s PR blitzes, told The News Hour with Jim Lehrer that the Bush team has taken packaging a president to a startling new level. He called their work “absolutely brilliant,” while conceding that including Bush’s head with the Mount Rushmore quartet may have been going a bit “too far.”*

**The image-building work extends to fiddling with documents that might reflect badly on the president. After Bush’s May 1, 2003, "Mission Accomplished” speech aboard the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln, the White House website ran a headline, “President Bush Announces Combat Operations in Iraq Have Ended.." But as TheMemoryHole.com revealed, once the insurrection proved stronger than expected, somebody went back and added the word “Major” before “Combat.”

Predictably, such transparent but skillful shaping of the President’s image horrifies those who think that Bush is a latter-day Wizard of Oz (conveniently forgetting that Clinton did the same thing, albeit less blatantly). They point with glee to ex—Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill’s remark that, in cabinet meetings, the President was like a blind man in a room full of deaf people. They wonder if Bush really calls the shots or whether he’s a hologram created by Dick Cheney and Karl Rove. They decry the abyss dividing the way the President is presented and what his administration is actually up to behind closed doors: Did he and Cheney privately joke about that big Halliburton contract in Iraq? Critics want to probe behind the myth and learn exactly who did what and when and why. They want to get “inside” the “real” George Bush.

Why? Much of any presidency’s meaning lies precisely in its constantly changing overlay of imagery, propaganda, rumor, and journalistic blather. To strip them away in search of the “real” president is like trying to find the real onion by peeling away the layers. This is especially true of George W. Bush, who, like John Kennedy four decades before him, has spawned an astonishing number of personas in a remarkably short time, many of them contradictory. Over the last four years we’ve had Bush as Regular Guy, Village Idiot, No-Nonsense CEO, Compassionate Conservative, latter-day Prince Hal, and, of course, Moby Dubya devouring any Democrat foolish enough to stray into his path. None of these myths is without its truth, and each has, at times, served the President’s purposes. What matters here is not so much George Bush the real man as the idea of “George Bush”–the images of the man that America has been peddled over the last four years.

#1: A Regular Guy

During the run-up to the 2002 congressional elections, Bush broke all records for the number of days a president spent campaigning for his party’s candidates. He seemed to be everywhere. Late one night on cable, supporters at a Republican rally explained why they liked him. Their reasons varied, to be sure (“He’s strong,” “He’s a real leader,” etc.), but were united by a common thread: The President was genuine, straightforward, a regular guy. Or as his advisor Karl Rove likes to put it, “He is who he is.”

There’s no denying that this is a potent tautology, identical to the one favored by no less a mensch than Popeye the Sailorman, but it does beg the larger question: Who is he? At first glance, one thing seems clear. He’s not a regular guy. In fact, Bush could almost be the archetype of the un-regular guy, the spoiled rich kid perpetually mocked by our culture from The Magnificent Ambersons’ unbearable Georgie to the high school snots in those 1980s John Hughes comedies. It’s worth recalling that “Junior” Bush comes not merely from privilege but long-standing privilege. On his mother’s side, he’s related both to the British royal family (he’s a distant cousin of Queen Elizabeth II) and to President Franklin Pierce; on the Bush side, he’s the grandson of U.S. Senator Prescott Bush, an old-school WASP of the Eastern Establishment, and, of course, the son of George H. W. Bush–Congressman, CIA boss, Nixon frontman at the Republican National Committee, Vice President, and Commander in Chief. Like his father, he attended Andover and Yale and then, for good measure, went to Harvard Business School. But his youth, which lasted until he was almost forty, was not exactly impressive. He was a lazy student (specializing in the Gentleman’s C), a tireless party animal with a DWI arrest in Maine, a lousy businessman, and a superb mama’s boy. Countless Americans of his generation followed a similar youthful path and wound up working for John Deere or standing in the unemployment line. They actually completed their military service, though; Dubya couldn’t be bothered. He ducked the Vietnam War by joining the Texas Air National Guard, jumping the queue to get in, and then, as we all now know, shortchanged his service with impunity: His dad was a congressman. Somehow, he wound up a rich man (estimated worth $9—$26 million) and President of the United States.

One might think such a background would have ordinary people fuming. Yet as Paul Fussell and others have so patiently noted, Americans don’t view class in the strict European way. Individuals are defined less by birth, which they can’t choose, than by personal style, which they can. In many ways, Bush does have the manner of a regular guy–his prodigal youth gives him an aura of rebellion against the hoity-toity ways of the elite. He enjoys sports and remains faithful, we’re told, to his wife. He likes folksy plain talk and dislikes people who put on airs. He doesn’t want to know all that much about current events. Even his onetime drinking troubles help establish his ordinary-guy bona fides: Everyone knows someone who’s had alcohol or drug

problems, and Americans admire those who fall and pick themselves up. A square during the sixties, when he was an Andover cheerleader and the chief Deke at Yale, he bristles at anything that smacks of bohemia or the counterculture. He is overt about his Christian faith, and in a country that’s ever more openly religious (39 percent of Americans claim to be born again), this does make him far more “regular” than most Democratic politicians, or even his own family. Where his father always came off as a faux Texan–“deep doo-doo” is not what littered the trail to the Alamo–Junior feels happiest in Texas, preferring the provincialism of its white oligarchy to the big-city ways back east, where people are uppity about his home state. Doubt his credentials, though, and he’ll instantly remind you that he went to Harvard and Yale. While Bush’s love for Texas is genuine–being “home” matters deeply to him–he’s politician enough to milk its symbolism as a political asset; hence his 1999 purchase of a ranch eight miles from the white-flight suburb of Crawford. Located amid one of the most reactionary enclaves in the nation, this sprawling homestead not only lets him escape the media’s prying eye but affords him chances to be photographed wearing cowboy boots and a belt buckle the size of a hubcap, manfully (and Reaganfully) cutting back brush. How many times in his life do you think he’s done this off-camera?*

*A lot of people work the Texas shtick. Although Molly Ivins went to Smith, got an M.A. from Columbia Journalism School, and was once a bureau chief for The New York Times, her own folksiness makes George W. Bush sound like George Plimpton.

It would be wrong to belabor the image of Bush as a weekend rancher, for that’s only a symptom of his real appeal. In a larger iconic sense, his public persona harks back to a vanishing yet still hardy ideal of white American masculinity, one embodied in today’s movies by Harrison Ford, who, rather like the President, is good at making wisecracks that don’t quite mask the surliness lying beneath. Like a less glamorous Jack Ryan or Indiana Jones, Bush comes across as a terse man of action whose pride is that he says what he means, means what he says, and if you don’t like it, too damn bad. The last president to court such an image was Harry Truman, who spent his final decades puffing up his reputation for straight shooting. Most regular guys can’t afford to adopt such attitude–unlike Dubya, they don’t have the connections to escape its consequences–but the fantasy appeals to them. That’s precisely why Bush has been sold as a self-confident straight-shooter by both his handlers and the conservative journalists who have crafted his myth. “George W. Bush doesn’t give a damn what you think of him,” wrote Tucker Carlson in a much-vaunted Talk profile back in 2000, ignoring all the ways this attitude might be insidious (and dishonest) in a man prepared to soft-pedal his right-wing ideology to momentarily woo swing voters. “That may be why you’ll vote for him for president.”

The Bush team tries to reinforce his virile image by stressing his physicality; perhaps he was a macho cheerleader. We’re told that he runs the mile in less than seven minutes (or did until he injured himself), ending the long national nightmare of Clinton’s jiggly pale thighs. We’re treated to displays like the tail-hook landing on the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln–his abbreviated time in the Air National Guard came in handy, after all–which demonstrated how dashing the President could be in a flight suit. Norman Mailer has suggested that Bush could have made “a world-class male model,” and though this wasn’t meant kindly, the old brawler was onto a truth: The President never seems looser than when he’s doing something purely physical. Bush was far more relaxed in that flight suit than he’d ever been in a business suit, let alone during any of his rare press conferences. In fact, the more you see him doing official business, the more you sense his tension at having to be presidential. It’s there in his peculiar stride across the White House Lawn, elbows out like a clichéd French pedestrian, palms facing apishly backward (an echo of those ears?). It’s there in the slightly clumsy way he whispers to his foreign guests as they stand before the media. It’s there in the narrowed eyes inherited from his father that greet any question he fears might contain a hidden fish hook.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Sore Winners puts it all in perspective . . . It takes on icons of both the left and the right, decoding the through-the-looking-glass landscape of contemporary American culture.” –Los Angeles Times “Sore Winners is one of the best books of political analysis I’ve read in the past five years. John Powers has an original and refreshing way of getting the reader to see politics differently.” –Bill Moyers“[A] bitingly sharp analysis . . . Powers assuredly navigates the reader through both the major (Saddam’s capture) and minor (Joe Millionaire) events that shaped our media-soaked culture over recent years.” –Vogue “[Powers] is a clever, quick-witted writer with a gift for the dead-on zinger — the Left’s answer to P.J. O’Rourke [and] David Brooks.” –The Washington Post Book World“Sore Winners rises above the shrieking din with its mix of pop culture criticismÉand its depressing yet dead-on examination of what Powers terms ‘Bush World.’” –Los Angeles "The best and the most persuasive. . . . The only one to try to tie all of the last 3 1/2 post-traumatic years together!" – The Buffalo News"Powers packs more sense in a quick sentence than others can fit into an entire book."– Colorado Springs Independent“John Powers’s Sore Winners is an angry but astonishingly good-humored and generous account of the degraded political and media culture of the Bush era. I can’t imagine a better guide for anyone trying to get his head screwed on right and mount a free-swinging attack on the worst president and the crassest popular culture in recent American history.”–David Denby, New Yorker film critic and author of American Sucker“Powers’s Sore Winners is surreally comprehensive, laserously observant, 85 percent correct, and refreshingly unshrill.”– David Foster Wallace“While reading this funny and engaging book, I felt the hair I had torn out reading David Brooks start to grow back.” – David Rees, author of Get Your War On“It’s so hard, these days, to cut through the noise and nonsense and get it right. The polymath Powers has done it, with this grand confection of wit, insight and blazing, level-headed honesty. Delicious!” – Ron Suskind, author of A Hope in the Unseen and The Price of Loyalty“A disturbing trip down memory lane that places the last four years in true, horrible relief. John Powers takes us into the funhouse — and then shows us a way out.”–Colson Whitehead, author of John Henry Days and The Colossus of New York“A bittersweet, breezy, smart look at current politics in the larger context of American culture – or what passes for it. Enough right-on digs at current icons to cover the cost of admission!” – Kirkus Reviews“Exhilaratingly insightfulÉPowers' brilliant synthesis and recap is invaluable in its coherence and incisiveness.” – Booklist

Cuprins

Introduction The Digital Presidency

Chapter 1 The Six Faces of George W. Bush

Chapter 2 From September 11 to 9/111: Birth of a Legend

Chapter 3 The Disquieting American, or The “Why Do They Hate Us?” Blues

Chapter 4 Idols and Survivors: Populist Social Darwinism

Chapter 5 Meta-Media Madness: We Distort, You Deride

Chapter 6 The Small Pleasures of Big-Box Culture

Chapter 7 Postcards from the Wedge

Epilogue Escape from Bush World

Afterword And You—And You—And You—And You Were There

Acknowledgments

A Select Bibliography

Index

Chapter 1 The Six Faces of George W. Bush

Chapter 2 From September 11 to 9/111: Birth of a Legend

Chapter 3 The Disquieting American, or The “Why Do They Hate Us?” Blues

Chapter 4 Idols and Survivors: Populist Social Darwinism

Chapter 5 Meta-Media Madness: We Distort, You Deride

Chapter 6 The Small Pleasures of Big-Box Culture

Chapter 7 Postcards from the Wedge

Epilogue Escape from Bush World

Afterword And You—And You—And You—And You Were There

Acknowledgments

A Select Bibliography

Index