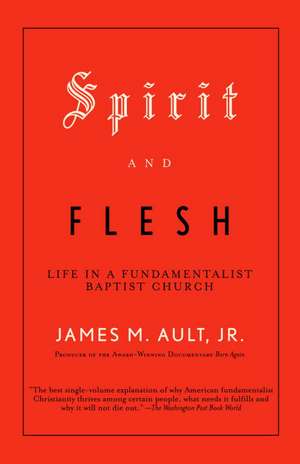

Spirit and Flesh: Life in a Fundamentalist Baptist Church

Autor James M Aulten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2005

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Christianity Today Book Award (2005), Massachusetts Book Award (MassBook) (2005)

Preț: 141.54 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 212

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.08€ • 28.35$ • 22.41£

27.08€ • 28.35$ • 22.41£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375702389

ISBN-10: 0375702385

Pagini: 433

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375702385

Pagini: 433

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

James M. Ault, Jr. was educated at Harvard and Brandeis universities. After teaching at Harvard and at Smith College, he made his first film, Born Again, a portrait of this fundamentalist Baptist congregation, which won a Blue Ribbon at the American Film Festival and was broadcast in the United States and abroad in 1987. He has since produced and directed a variety of documentary programs for the Lilly Endowment, the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Episcopal Church Foundation, and other organizations. He lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Meeting

You're either for God or against him.

I remember trying to muster the courage to first pick up the telephone to call the Reverend Frank Valenti. It was February 1983, the middle of Ronald Reagan's first term as president and a moment of ascending strength for a popular conservatism that was then transforming American politics. As a young sociologist having recently completed my Ph.D., I was several months into a research project to better understand what I called the conservative "pro-family" movement. By that I meant those groups struggling to defend what they saw as traditional family values through a constellation of enthusiasms including opposition to abortion, sex education, homosexual rights and the equal rights amendment. While the New Right as a political coalition also contained Libertarians and old-style Republicans, it was this popular movement animated by concerns around family and gender that gave new-right conservatism its mass base and political clout.[1]

My apprehension about calling Pastor Valenti stemmed from the suspicion and hostility that hovered over my first contacts with conservatives. I had sought them out near my home in Northampton, Massachusetts, a county seat on the Connecticut River in the western part of the state, where I had moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to teach sociology at Smith College. My first contacts had been with grassroots activists in right-to-life groups and in Birthright, an antiabortion counseling group. They were almost always wary and guarded, imagining that a sociologist--and one teaching at Smith College at that--would be prejudiced against all they stood for. Since I often sensed among them the lurking suspicion that I was an enemy spy ultimately up to no good, I felt it important not to do or say things that would stamp me as an opponent. This constant vigilance was often more exhausting than making one's way in a foreign country where you do not know the language or customs. In that case, at least, ignorance did not mark you as the enemy.

I took care in dress, demeanor and speech not to do anything that would offend. Yet sometimes seemingly inconsequential things would trigger distrust. For example, I once asked a soft-spoken woman who counseled pregnant teenagers in a Birthright office about contemporary attitudes toward "sexuality."

"What do you mean by that word?" she snapped with an alarmed look in her eyes. "I can't stand when people use it. It always makes it seem more important than it should be!"

I had been referred to Pastor Valenti by Bill and Karen Fournier, a Catholic couple active in right-to-life and other conservative causes in the Worcester area. They reported to me with delight that Valenti's wife, Sharon, and her mother had just gained public notoriety by protesting a youth conference, "Dealing with Feelings," sponsored by Family Planning Services of Central Massachusetts. The conference had been held at a local Congregational church and had featured Dr. Sol Gordon, a noted sex educator. The Fourniers showed me an article on the protest in Worcester's Evening Gazette, in which Sharon Valenti's mother, Ada Morse, was quoted as saying, "This assault on our children's mores and morals is by an insidious humanist group hiding behind a veil of feigned decency, voraciously seeking to undermine patriotism, obedience, academics and morality and supplant them with subversion, rebellion, ignorance and sexual disorientation." This was the kind of conservatism I was looking for.

It had been the Fourniers' own campaign in their local schools against Our Bodies, Ourselves, the feminist health-care book, that had brought them to the attention of a correspondent I knew who interviewed them for a National Public Radio program on book banning. Though devout Catholics, Bill and Karen Fournier were unhappy with what they saw as the liberal and humanist directions of the Catholic Church. Two years earlier, Karen, a petite and energetic woman in her thirties, had asked a young priest teaching in her daughter's parochial school to reintroduce opening prayer in his classes. By then, only two teachers in the entire school were carrying on that practice, she reported. He refused, saying "It would upset some of the students."

What caused Karen greater distress was seeing her oldest daughter, then in seventh grade, come home from school wearing jeans and makeup and swearing. This caused "a heaviness in my heart," she said, which she carried with her to Washington, D.C., in 1980, to attend the first Family Forum, a conservative conference on defending traditional family values. There, she recalled, "God brought me to Raymond Moore's session on home schools." Soon after, she and Bill took their four children out of parochial school and, with several like-minded families, started their own home school, which they called the Holy Family Academy.

I made several trips to the Worcester area that fall to visit the Holy Family Academy, run in a renovated barn attached to the Fourniers' home, and to interview some of the close circle of parents involved. The Fourniers themselves took more easily than other conservatives I met to conversing with outsiders like me. This was not because they were less radical or militant in their conservatism. On the contrary. But they seemed more adept at articulating their positions in the face of opposed views, in part because they were able to notice and handle contrary assumptions underlying them. For example, though I felt comfortable describing Our Bodies, Ourselves as "a feminist health-care book," Bill, who had done graduate work in philosophy at Boston College, contested "the very word 'health.'"

"That particular book," he explained, "takes the word 'health' and calls 'healthy' the lifestyles it happens to agree with--like extramarital sex, homosexuality and masturbation--and 'unhealthy' or 'sick' lifestyles it happens to disagree with."

"They would like to change society's values totally," Karen explained quietly, "especially in the areas of sexuality and family. Using this book is one way of doing it, to get rid of the traditional family."

In retrospect, I realize, the Fourniers helped prepare me to meet the Valentis and their church. I remember walking a picket line with Bill Fournier one cold, sunny December afternoon in downtown Worcester outside a tall, turn-of-the-century office building that housed a Planned Parenthood clinic. As at other small demonstrations I had once attended as an antiwar activist, people came and went throughout the day, greeting and kidding friends. Some unloaded a pile of signs with stenciled slogans: stop murdering babies, end death clinics and so on. Others carefully assembled more elaborate and well-worn homemade posters with photos of bloody "fetuses" (or "babies") and lengthier hand-printed text. Bill introduced me to those he knew by saying, "This is Jim. He's doing a book on pro-life."

"Great! We need that!" several offered in hearty encouragement for a book they assumed would affirm their cause. I felt strange about suddenly being taken for a fellow partisan, though I could not help appreciating the relief Bill's tact provided.

Later that afternoon some of the bolder demonstrators sneaked into the building and rode the elevator up to the Planned Parenthood floor. Bill and I went along. Soon after we arrived, in the reception area, a commotion erupted. A policeman arrived, and, as he herded us to the elevator, some took the opportunity to speak their views: "They're murdering babies in there!... Next they'll be killing old people and the handicapped!" I was unprepared for the icy looks and hateful stares from the Planned Parenthood staff as I stood there mutely looking on, now suddenly on the other side of a line of battle.

The Fourniers said that before I finished my research in the Worcester area I should go see "the Valentis' school." Just as it had been Karen Fournier's inspiration to start the Holy Family Academy, it had been Sharon Valenti's idea to start the Christian Academy attached to their fundamentalist church. What had moved her to do so, Sharon later explained to me, was picking up some textbooks from her children's public school and being "totally shocked at what the humanist view was teaching."

"It was sex education that really bothered me," she said, "because it was from a perverted standpoint. It wasn't abstinence. They taught about different contraceptives and how to use them, and encouraged the petting and the experiencing. The Bible says to abstain from all those things. They think they're not teaching any kind of morals," she allowed, "but you can't do that. You're either for God or against him."

In the wrenching reversal of American politics toward conservatism over the past quarter century, no institution has been more decisive than local fundamentalist or evangelical churches.[2] Week in, week out, thousands of such churches across the nation educate members on issues of the day, arousing and directing their political outrage and concern. Such churches have provided a ready-made organization for both Pat Robertson's Christian Coalition and, before it, Jerry Falwell's more radical Moral Majority. At the height of the Moral Majority's influence in American politics in the 1980s, most of its chapters across the country, like the one in Massachusetts, were headed by fundamentalist preachers trained at Jerry Falwell's Liberty Baptist College or at schools affiliated with the Baptist Bible Fellowship, a loose federation of rigorously independent fundamentalist churches to which Falwell had initially belonged. Moreover, fundamentalists in this independent Baptist tradition represented the harder-edged, more aggressive and tougher strain of conservatives on the American scene. This fact sharpened my fears as I first picked up my phone to call the Reverend Valenti.

I introduced myself, saying the Fourniers had suggested I call, and briefly described my study. Sure, he would be willing to speak with me, Valenti said, and we made an appointment to meet in his office. I did not take any notes of our conversation. I would soon get his story face-to-face. The only thing that stuck in my mind was something he said quite spontaneously toward the end. "You know something, Jim," he said, already quite personable with me, "I used to be in the garage business, and that was easy compared to running a church. I got eleven people working under me right now--you know, with the school and the church. And you know what? Managing people is one of the hardest things to do. It just flat ain't easy!" A mechanic-turned-preacher, I mused. His candor was refreshing, and I appreciated his observations about the challenges of managing people. Little did I know what role those challenges would play in the fate of his church, or how much change in my own life hinged on picking up the phone that day.

I knew very little about Worcester when I set out on a cold, bright February afternoon to make the hour-and-a-quarter drive eastward from Northampton to meet Pastor Valenti. In time I would become more familiar with its leading industrial firms, such as Norton Company, with the 360-degree views from Mount Wachusett rising all by itself out of the Worcester plateau, and with the discrete neighborhoods making up that city: Leicester Square, College Hill, Quinsigamond Village.

Even though it is the second-largest city in the industrial state of Massachusetts, Worcester struck me as a museum piece, with its old craft-based industries, wire-pulling and machine tools, and its abandoned downtown. From an academic's point of view, the last time Worcester made news was in 1911, when Sigmund Freud, on his first trip to the United States, chose to visit the then-prestigious psychology department of Clark University. Since then, it seemed, centralization and specialization had turned Worcester, like so many American cities flourishing at the beginning of the twentieth century, into a backwater--but a backwater that had changed, nevertheless, in many ways. Among other things, the crisscrossing interstate highways and the ubiquitous automobile had turned the rural towns and farm communities on its outskirts into ungainly suburbs, where old-time residents now complained about needing to lock their doors.

Following Valenti's directions, I exited the interstate in one such suburb on Worcester's perimeter and found myself in an eclectic area. In a short commercial strip, the common installations of mass society--an outlet for electronic banking, McDonald's, Bonanza--sat alongside establishments such as Danny's Lounge, the Valley Bait Shop and Mike Dukas' Diner, which looked like an Airstream caravan that had landed on cement blocks. On the residential streets, proper suburban homes with neatly trimmed lawns sat alongside idiosyncratic piecemeal constructions and homes with barns and horses. Commercial vans parked in driveways, derelict pieces of machinery in the yard and handmade signs--sewing done or curios 'n things--suggested the presence of family businesses. It was an area where postwar suburban sprawl blended with older farm communities and long-stagnant mill towns of the New England hinterland, and where Frank and Sharon Valenti had grown up and founded their church.

As I drove along a wooded suburban road, the terrain suddenly opened to a large grassy field on my left. A small clapboard house sat close by the road, and behind it, surrounded by a macadamized parking lot, was a curious conglomeration of buildings. In the front stood an old rectangular building made of red brick with white clapboard dormers. Looming behind it was a large new warehouse-like building finished with gray aluminum siding. A wooden sign at the driveway told me I had arrived: the shawmut river baptist church--the reverend frank valenti, pastor.

I found my way to Pastor Valenti's office on the second floor of the red brick building, which I learned used to house a bakery. It had been purchased with a large parcel of land for an extremely favorable price from two sisters whose family had worked at the Salvation Army. "The Lord's providence," those on both sides of the transaction had affirmed. Valenti's secretary showed me into an office with wall-to-wall red-orange shag carpeting. Light from the one large window and from banks of fluorescent lights set in a drop ceiling glared off the faux wood paneling.

Pastor Valenti rose from behind his desk to shake my hand, and I sat down across from him. He was portly and about my height, five feet eight, and was wearing a snugly fitting three-piece suit, a thickly knotted tie and a large gold watch. He had short, neatly groomed black hair, which came down in full sideburns to frame the face of a comic: sheepish brown eyes, a slightly hooked nose and, set between two full cheeks, a restless mouth always ready, I soon saw, to smirk, grimace or smile. The olive green bookshelves covering the wall behind him held a library dominated by a half-dozen sets of like-colored volumes--Bible concordances and commentaries. A map of the area with markings and pushpins was Scotch-taped to the wall in the far corner of the room--an abandoned tool, I would learn, of earlier efforts at "systematic" evangelizing.

From the Hardcover edition.

You're either for God or against him.

I remember trying to muster the courage to first pick up the telephone to call the Reverend Frank Valenti. It was February 1983, the middle of Ronald Reagan's first term as president and a moment of ascending strength for a popular conservatism that was then transforming American politics. As a young sociologist having recently completed my Ph.D., I was several months into a research project to better understand what I called the conservative "pro-family" movement. By that I meant those groups struggling to defend what they saw as traditional family values through a constellation of enthusiasms including opposition to abortion, sex education, homosexual rights and the equal rights amendment. While the New Right as a political coalition also contained Libertarians and old-style Republicans, it was this popular movement animated by concerns around family and gender that gave new-right conservatism its mass base and political clout.[1]

My apprehension about calling Pastor Valenti stemmed from the suspicion and hostility that hovered over my first contacts with conservatives. I had sought them out near my home in Northampton, Massachusetts, a county seat on the Connecticut River in the western part of the state, where I had moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to teach sociology at Smith College. My first contacts had been with grassroots activists in right-to-life groups and in Birthright, an antiabortion counseling group. They were almost always wary and guarded, imagining that a sociologist--and one teaching at Smith College at that--would be prejudiced against all they stood for. Since I often sensed among them the lurking suspicion that I was an enemy spy ultimately up to no good, I felt it important not to do or say things that would stamp me as an opponent. This constant vigilance was often more exhausting than making one's way in a foreign country where you do not know the language or customs. In that case, at least, ignorance did not mark you as the enemy.

I took care in dress, demeanor and speech not to do anything that would offend. Yet sometimes seemingly inconsequential things would trigger distrust. For example, I once asked a soft-spoken woman who counseled pregnant teenagers in a Birthright office about contemporary attitudes toward "sexuality."

"What do you mean by that word?" she snapped with an alarmed look in her eyes. "I can't stand when people use it. It always makes it seem more important than it should be!"

I had been referred to Pastor Valenti by Bill and Karen Fournier, a Catholic couple active in right-to-life and other conservative causes in the Worcester area. They reported to me with delight that Valenti's wife, Sharon, and her mother had just gained public notoriety by protesting a youth conference, "Dealing with Feelings," sponsored by Family Planning Services of Central Massachusetts. The conference had been held at a local Congregational church and had featured Dr. Sol Gordon, a noted sex educator. The Fourniers showed me an article on the protest in Worcester's Evening Gazette, in which Sharon Valenti's mother, Ada Morse, was quoted as saying, "This assault on our children's mores and morals is by an insidious humanist group hiding behind a veil of feigned decency, voraciously seeking to undermine patriotism, obedience, academics and morality and supplant them with subversion, rebellion, ignorance and sexual disorientation." This was the kind of conservatism I was looking for.

It had been the Fourniers' own campaign in their local schools against Our Bodies, Ourselves, the feminist health-care book, that had brought them to the attention of a correspondent I knew who interviewed them for a National Public Radio program on book banning. Though devout Catholics, Bill and Karen Fournier were unhappy with what they saw as the liberal and humanist directions of the Catholic Church. Two years earlier, Karen, a petite and energetic woman in her thirties, had asked a young priest teaching in her daughter's parochial school to reintroduce opening prayer in his classes. By then, only two teachers in the entire school were carrying on that practice, she reported. He refused, saying "It would upset some of the students."

What caused Karen greater distress was seeing her oldest daughter, then in seventh grade, come home from school wearing jeans and makeup and swearing. This caused "a heaviness in my heart," she said, which she carried with her to Washington, D.C., in 1980, to attend the first Family Forum, a conservative conference on defending traditional family values. There, she recalled, "God brought me to Raymond Moore's session on home schools." Soon after, she and Bill took their four children out of parochial school and, with several like-minded families, started their own home school, which they called the Holy Family Academy.

I made several trips to the Worcester area that fall to visit the Holy Family Academy, run in a renovated barn attached to the Fourniers' home, and to interview some of the close circle of parents involved. The Fourniers themselves took more easily than other conservatives I met to conversing with outsiders like me. This was not because they were less radical or militant in their conservatism. On the contrary. But they seemed more adept at articulating their positions in the face of opposed views, in part because they were able to notice and handle contrary assumptions underlying them. For example, though I felt comfortable describing Our Bodies, Ourselves as "a feminist health-care book," Bill, who had done graduate work in philosophy at Boston College, contested "the very word 'health.'"

"That particular book," he explained, "takes the word 'health' and calls 'healthy' the lifestyles it happens to agree with--like extramarital sex, homosexuality and masturbation--and 'unhealthy' or 'sick' lifestyles it happens to disagree with."

"They would like to change society's values totally," Karen explained quietly, "especially in the areas of sexuality and family. Using this book is one way of doing it, to get rid of the traditional family."

In retrospect, I realize, the Fourniers helped prepare me to meet the Valentis and their church. I remember walking a picket line with Bill Fournier one cold, sunny December afternoon in downtown Worcester outside a tall, turn-of-the-century office building that housed a Planned Parenthood clinic. As at other small demonstrations I had once attended as an antiwar activist, people came and went throughout the day, greeting and kidding friends. Some unloaded a pile of signs with stenciled slogans: stop murdering babies, end death clinics and so on. Others carefully assembled more elaborate and well-worn homemade posters with photos of bloody "fetuses" (or "babies") and lengthier hand-printed text. Bill introduced me to those he knew by saying, "This is Jim. He's doing a book on pro-life."

"Great! We need that!" several offered in hearty encouragement for a book they assumed would affirm their cause. I felt strange about suddenly being taken for a fellow partisan, though I could not help appreciating the relief Bill's tact provided.

Later that afternoon some of the bolder demonstrators sneaked into the building and rode the elevator up to the Planned Parenthood floor. Bill and I went along. Soon after we arrived, in the reception area, a commotion erupted. A policeman arrived, and, as he herded us to the elevator, some took the opportunity to speak their views: "They're murdering babies in there!... Next they'll be killing old people and the handicapped!" I was unprepared for the icy looks and hateful stares from the Planned Parenthood staff as I stood there mutely looking on, now suddenly on the other side of a line of battle.

The Fourniers said that before I finished my research in the Worcester area I should go see "the Valentis' school." Just as it had been Karen Fournier's inspiration to start the Holy Family Academy, it had been Sharon Valenti's idea to start the Christian Academy attached to their fundamentalist church. What had moved her to do so, Sharon later explained to me, was picking up some textbooks from her children's public school and being "totally shocked at what the humanist view was teaching."

"It was sex education that really bothered me," she said, "because it was from a perverted standpoint. It wasn't abstinence. They taught about different contraceptives and how to use them, and encouraged the petting and the experiencing. The Bible says to abstain from all those things. They think they're not teaching any kind of morals," she allowed, "but you can't do that. You're either for God or against him."

In the wrenching reversal of American politics toward conservatism over the past quarter century, no institution has been more decisive than local fundamentalist or evangelical churches.[2] Week in, week out, thousands of such churches across the nation educate members on issues of the day, arousing and directing their political outrage and concern. Such churches have provided a ready-made organization for both Pat Robertson's Christian Coalition and, before it, Jerry Falwell's more radical Moral Majority. At the height of the Moral Majority's influence in American politics in the 1980s, most of its chapters across the country, like the one in Massachusetts, were headed by fundamentalist preachers trained at Jerry Falwell's Liberty Baptist College or at schools affiliated with the Baptist Bible Fellowship, a loose federation of rigorously independent fundamentalist churches to which Falwell had initially belonged. Moreover, fundamentalists in this independent Baptist tradition represented the harder-edged, more aggressive and tougher strain of conservatives on the American scene. This fact sharpened my fears as I first picked up my phone to call the Reverend Valenti.

I introduced myself, saying the Fourniers had suggested I call, and briefly described my study. Sure, he would be willing to speak with me, Valenti said, and we made an appointment to meet in his office. I did not take any notes of our conversation. I would soon get his story face-to-face. The only thing that stuck in my mind was something he said quite spontaneously toward the end. "You know something, Jim," he said, already quite personable with me, "I used to be in the garage business, and that was easy compared to running a church. I got eleven people working under me right now--you know, with the school and the church. And you know what? Managing people is one of the hardest things to do. It just flat ain't easy!" A mechanic-turned-preacher, I mused. His candor was refreshing, and I appreciated his observations about the challenges of managing people. Little did I know what role those challenges would play in the fate of his church, or how much change in my own life hinged on picking up the phone that day.

I knew very little about Worcester when I set out on a cold, bright February afternoon to make the hour-and-a-quarter drive eastward from Northampton to meet Pastor Valenti. In time I would become more familiar with its leading industrial firms, such as Norton Company, with the 360-degree views from Mount Wachusett rising all by itself out of the Worcester plateau, and with the discrete neighborhoods making up that city: Leicester Square, College Hill, Quinsigamond Village.

Even though it is the second-largest city in the industrial state of Massachusetts, Worcester struck me as a museum piece, with its old craft-based industries, wire-pulling and machine tools, and its abandoned downtown. From an academic's point of view, the last time Worcester made news was in 1911, when Sigmund Freud, on his first trip to the United States, chose to visit the then-prestigious psychology department of Clark University. Since then, it seemed, centralization and specialization had turned Worcester, like so many American cities flourishing at the beginning of the twentieth century, into a backwater--but a backwater that had changed, nevertheless, in many ways. Among other things, the crisscrossing interstate highways and the ubiquitous automobile had turned the rural towns and farm communities on its outskirts into ungainly suburbs, where old-time residents now complained about needing to lock their doors.

Following Valenti's directions, I exited the interstate in one such suburb on Worcester's perimeter and found myself in an eclectic area. In a short commercial strip, the common installations of mass society--an outlet for electronic banking, McDonald's, Bonanza--sat alongside establishments such as Danny's Lounge, the Valley Bait Shop and Mike Dukas' Diner, which looked like an Airstream caravan that had landed on cement blocks. On the residential streets, proper suburban homes with neatly trimmed lawns sat alongside idiosyncratic piecemeal constructions and homes with barns and horses. Commercial vans parked in driveways, derelict pieces of machinery in the yard and handmade signs--sewing done or curios 'n things--suggested the presence of family businesses. It was an area where postwar suburban sprawl blended with older farm communities and long-stagnant mill towns of the New England hinterland, and where Frank and Sharon Valenti had grown up and founded their church.

As I drove along a wooded suburban road, the terrain suddenly opened to a large grassy field on my left. A small clapboard house sat close by the road, and behind it, surrounded by a macadamized parking lot, was a curious conglomeration of buildings. In the front stood an old rectangular building made of red brick with white clapboard dormers. Looming behind it was a large new warehouse-like building finished with gray aluminum siding. A wooden sign at the driveway told me I had arrived: the shawmut river baptist church--the reverend frank valenti, pastor.

I found my way to Pastor Valenti's office on the second floor of the red brick building, which I learned used to house a bakery. It had been purchased with a large parcel of land for an extremely favorable price from two sisters whose family had worked at the Salvation Army. "The Lord's providence," those on both sides of the transaction had affirmed. Valenti's secretary showed me into an office with wall-to-wall red-orange shag carpeting. Light from the one large window and from banks of fluorescent lights set in a drop ceiling glared off the faux wood paneling.

Pastor Valenti rose from behind his desk to shake my hand, and I sat down across from him. He was portly and about my height, five feet eight, and was wearing a snugly fitting three-piece suit, a thickly knotted tie and a large gold watch. He had short, neatly groomed black hair, which came down in full sideburns to frame the face of a comic: sheepish brown eyes, a slightly hooked nose and, set between two full cheeks, a restless mouth always ready, I soon saw, to smirk, grimace or smile. The olive green bookshelves covering the wall behind him held a library dominated by a half-dozen sets of like-colored volumes--Bible concordances and commentaries. A map of the area with markings and pushpins was Scotch-taped to the wall in the far corner of the room--an abandoned tool, I would learn, of earlier efforts at "systematic" evangelizing.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“The best single-volume explanation of why American fundamentalist Christianity thrives among certain people, what needs it fulfills and why it will not die out.” –The Washington Post Book World“An absorbing, groundbreaking, and intimate tale. . . . An ethnographic study that often reads like a novel.” –The Christian Science Monitor“Not just a first-rate piece of sociological journalism. Ault weaves his own story into the book, and . . . gives Spirit and Flesh a warmth and humanity that set it apart.” –The San Francisco Chronicle“This brilliant book is essential for anyone who wants to better understand fundamentalism — or for fundamentalists who desire to understand how they are viewed by others.” –Christianity Today

Premii

- Christianity Today Book Award Award of Merit, 2005

- Massachusetts Book Award (MassBook) Honor Book, 2005