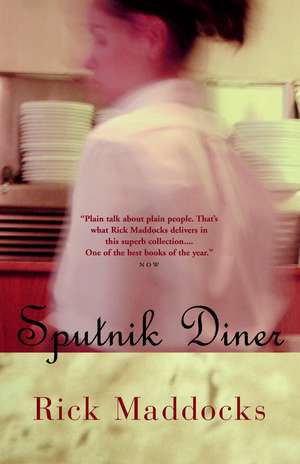

Sputnik Diner

Autor Rick Maddocksen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2002

Travelling on Highway 3, along the upper lip of Lake Erie and through a moustache of tobacco fields and sky, we arrive in Nanticoke, Ontario. At the heart of the town is the Sputnik Diner, a smoky grill where the jukebox whirs out an ever-changing soundtrack. Navigating their way through the lies and sexual betrayals are Grace, waitress and self-defeating artist; Buzz, who offers the cook's eye view of the eccentric patrons and staff; and Marcel, the gruff French-Canadian owner who doles out hilarious malapropisms and his own peculiar brand of hospitality.

In muscular prose, Maddocks traces the lives of flawed, gutsy, and utterly loveable characters: an immigrant family from Wales, struggling to find their place in the ragged, darkly absurd world of tobacco-belt Ontario; two young brothers who steal the family car and try to come to grips with their father's cancer out on the dinosaur mini-putt course in the pouring rain; and Grace, who seeks out her birth parents only to confront the dizzying epiphanies of that momentous discovery. There are others too, whose stalled dreams, gritty hopes and humour spark through the Sputnik Diner universe.

Preț: 124.52 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 187

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.83€ • 24.79$ • 19.67£

23.83€ • 24.79$ • 19.67£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780676973792

ISBN-10: 0676973795

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0676973795

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

Born in 1970, Rick Maddocks has been published in numerous literary journals and anthologies. The opening story of Sputnik Diner won Prairie Fire’s Long Fiction Competition and was the winner of a Western Magazine Award. He lives in Vancouver.

Extras

Plane People

In the summer of 1981, two months before my family landed here, a man fell from the sky over Nanticoke and hit the roof of the mall seconds before his parachute blossomed out of his pack like a red and white silk handkerchief. The rest of him pollinated the employees’ parking lot–A&P cashiers’ hatchbacks, managers’ sedans, a dumpster–but the whole county felt the aftershock. When Dad took up a job offer from SteelCan, packing up me, Mam and Sal and leaving South Wales for the north shore of Lake Erie, the skydiver was still falling. Always in the same rehearsed, hushed tones from the locals’ lips: Nice guy. Good friend of the De Konnings who run the airport. Had a wife, couple of kids. Gave lessons out there, real safety-first fella. Packed his own chute every time. Said he was even in the running for the national team. Wouldn’t you just figure, eh? Made the same jump a thousand times. These words were wrapped up by a quiet nod and a stare that left your face slowly before it settled into space. Later we’d hear how the skydiving school was in financial trouble, how Nanticoke Public Works guys were busy out back at the mall for weeks afterwards. Steamrollers, mops, sprayers. Gallons of paint and tar. Yet in early August, when my sister Sal and I walked our brand new Supercycles over the yellow lines of the employees’ parking lot, the blood still showed there.

* * *

My family didn’t land in Nanticoke exactly. We were in an Oldsmobile travelling west on Highway 3, crossing the upper lip of Lake Erie through a moustache of tobacco fields and sky. My head was still full of the exotic cars I’d seen since landing in Toronto. Back on the 401 they hissed under street lights that bowed over the superhighway like sunflowers of steel and glass. But gradually, over two flat hours and a series of exits and off-ramps, cars gave way to pick-up trucks gave way to open road, until we encountered only the odd blare of headlights every few miles. Wind was a blow-dryer through the back window. And I was drunk on countryside, the flatness and ragged symmetry of it, the names of the small, foreign towns we passed through–Caledonia, Garnet, Hagersville, Jarvis–which, index and all, were nowhere to be found in my Collins Illustrated Atlas.

Twenty minutes west of Jarvis, our driver pointed over the steering wheel at a blush of pink on the horizon. Pink street lights that, though miles ahead on the flat highway, flared up into the darkening sky. “There she blows,” he said. His name was Tom Gadd and he’d driven us a hundred and forty kilometres down from Toronto in the plush burgundy interior of a Delta 88. “There’s your new home.”

Sal, curled up on Mam’s other side in the back seat, surfaced from sleep and panicked at the fields outside the window. “We’re lost, aren’t we?” She broke into tears. “We’re lost. We’re lost.”

“No, Sal. No.” Mam smoothed down my sister’s long dark hair, the soft melody of her voice leaning. “Bad dream, that’s all. We’ll be there soon.”

Gadd looked in the rear-view, then laughed amiably at Dad sitting beside him. “Cute,” he said. Dad laughed politely back.

After a minute Sal fell back asleep, her cheeks still damp. She was only nine, a year and a half younger than me, and because of her birth defect, I was never allowed to forget I was her big brother. When she was delivered her left eye swung inward so her pupil was facing the bridge of her nose. Mam and Dad waited till she was three–for her skull to grow, I figured–to okay the operation. The doctor plucked her eyeball clean out of it’s socket, set it on a metal platform at her cheekbone, pivoted it around and placed it back in her head. Voilà. In memory I was sitting at the foot of her hospital bed watching the whole procedure, Sal’s eye staring back at me from its own little steel podium. But Dad said no, I was at Nana and Grampa’s house watching wrestling. Even he wasn’t allowed in the operating room, he said.

He was in there for Sal’s delivery though. When Mam was in labour with me, Dad was off in the north of England with his Swansea rugby team. He was almost famous back home. He played twice for Wales back in 1971, and swore he would’ve got a string of international appearances except he broke his leg in the first half of his second match. “Your father missed your infancy playing that bloody game,” Mam said. Dad said she was bitter; rugby was always the other woman.

But afterwards he made it up to her through Sal. He was there to hear how, during her surgery, Sal’s retina was jarred a little by accident, stretched, so that later in life she could lose sight in her bum eye altogether. And how six years later the eye acted up whenever Sal got overexcited or, as Mam said, “all of a doodah.” Not only did her eye swing back to its old haunt like an alcoholic, but her hands shook as if drying nail polish and her mouth tightened and froze in a severe pucker. It was a sort of giddy trance. Embarrassed the hell out of me. But Dad said, “Just pretend she’s sleeping,” like she was now, in the back seat of a fancy American car purring down a black crickety Ontario highway with Mam singing “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean” into her hair.

In the summer of 1981, two months before my family landed here, a man fell from the sky over Nanticoke and hit the roof of the mall seconds before his parachute blossomed out of his pack like a red and white silk handkerchief. The rest of him pollinated the employees’ parking lot–A&P cashiers’ hatchbacks, managers’ sedans, a dumpster–but the whole county felt the aftershock. When Dad took up a job offer from SteelCan, packing up me, Mam and Sal and leaving South Wales for the north shore of Lake Erie, the skydiver was still falling. Always in the same rehearsed, hushed tones from the locals’ lips: Nice guy. Good friend of the De Konnings who run the airport. Had a wife, couple of kids. Gave lessons out there, real safety-first fella. Packed his own chute every time. Said he was even in the running for the national team. Wouldn’t you just figure, eh? Made the same jump a thousand times. These words were wrapped up by a quiet nod and a stare that left your face slowly before it settled into space. Later we’d hear how the skydiving school was in financial trouble, how Nanticoke Public Works guys were busy out back at the mall for weeks afterwards. Steamrollers, mops, sprayers. Gallons of paint and tar. Yet in early August, when my sister Sal and I walked our brand new Supercycles over the yellow lines of the employees’ parking lot, the blood still showed there.

* * *

My family didn’t land in Nanticoke exactly. We were in an Oldsmobile travelling west on Highway 3, crossing the upper lip of Lake Erie through a moustache of tobacco fields and sky. My head was still full of the exotic cars I’d seen since landing in Toronto. Back on the 401 they hissed under street lights that bowed over the superhighway like sunflowers of steel and glass. But gradually, over two flat hours and a series of exits and off-ramps, cars gave way to pick-up trucks gave way to open road, until we encountered only the odd blare of headlights every few miles. Wind was a blow-dryer through the back window. And I was drunk on countryside, the flatness and ragged symmetry of it, the names of the small, foreign towns we passed through–Caledonia, Garnet, Hagersville, Jarvis–which, index and all, were nowhere to be found in my Collins Illustrated Atlas.

Twenty minutes west of Jarvis, our driver pointed over the steering wheel at a blush of pink on the horizon. Pink street lights that, though miles ahead on the flat highway, flared up into the darkening sky. “There she blows,” he said. His name was Tom Gadd and he’d driven us a hundred and forty kilometres down from Toronto in the plush burgundy interior of a Delta 88. “There’s your new home.”

Sal, curled up on Mam’s other side in the back seat, surfaced from sleep and panicked at the fields outside the window. “We’re lost, aren’t we?” She broke into tears. “We’re lost. We’re lost.”

“No, Sal. No.” Mam smoothed down my sister’s long dark hair, the soft melody of her voice leaning. “Bad dream, that’s all. We’ll be there soon.”

Gadd looked in the rear-view, then laughed amiably at Dad sitting beside him. “Cute,” he said. Dad laughed politely back.

After a minute Sal fell back asleep, her cheeks still damp. She was only nine, a year and a half younger than me, and because of her birth defect, I was never allowed to forget I was her big brother. When she was delivered her left eye swung inward so her pupil was facing the bridge of her nose. Mam and Dad waited till she was three–for her skull to grow, I figured–to okay the operation. The doctor plucked her eyeball clean out of it’s socket, set it on a metal platform at her cheekbone, pivoted it around and placed it back in her head. Voilà. In memory I was sitting at the foot of her hospital bed watching the whole procedure, Sal’s eye staring back at me from its own little steel podium. But Dad said no, I was at Nana and Grampa’s house watching wrestling. Even he wasn’t allowed in the operating room, he said.

He was in there for Sal’s delivery though. When Mam was in labour with me, Dad was off in the north of England with his Swansea rugby team. He was almost famous back home. He played twice for Wales back in 1971, and swore he would’ve got a string of international appearances except he broke his leg in the first half of his second match. “Your father missed your infancy playing that bloody game,” Mam said. Dad said she was bitter; rugby was always the other woman.

But afterwards he made it up to her through Sal. He was there to hear how, during her surgery, Sal’s retina was jarred a little by accident, stretched, so that later in life she could lose sight in her bum eye altogether. And how six years later the eye acted up whenever Sal got overexcited or, as Mam said, “all of a doodah.” Not only did her eye swing back to its old haunt like an alcoholic, but her hands shook as if drying nail polish and her mouth tightened and froze in a severe pucker. It was a sort of giddy trance. Embarrassed the hell out of me. But Dad said, “Just pretend she’s sleeping,” like she was now, in the back seat of a fancy American car purring down a black crickety Ontario highway with Mam singing “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean” into her hair.

Recenzii

“Accurate, funny and vivid, Sputnik Diner is full of big truths about mid-size Canadian life. Rick Maddocks knows his world well, and delivers it. This is an impressive debut.” – Michael Winter

“[An] impressive talent…. Like Alice Munro, whose works share the common terrain of late-20th-century Ontario, Maddocks’ skill lies in turning out vivid and compelling characters. [His] detailed observations speak of a warm affection for the mess of family life and the rhythms of small town living.” – Quill & Quire

“Sputnik Diner is a bona fide gem – a deeply felt suite of short stories that chronicle a Welsh family’s dislocating arrival into the strange new world of a small Ontario town. Maddocks is a calmly lyrical talent.” – Vancouver Magazine

“Terrific…. Subtly portrayed…. Throughout Maddocks’s work, there are strong echoes of dirty-realist American writers like Tobias Wolff and Frederick Barthelme. Like them, he’s at his best when he keeps his writing lean and unsentimental…. Maddocks strikes [many] notes of grace throughout Sputnik Diner. While things don't turn out so well for the folks in Nanticoke, there's something beautiful in the way they fall out of the sky.” – The Globe and Mail

“Maddocks eschews showy writer’s tools, … relying instead on a painter's eye for detail and colour. The writing appeals to the reader's visual imagination and makes for effortless reading; there are times when Maddocks achieves that most prized of writing moments -- the transparent text, when the gap between reader and story seems to disappear. When Maddocks does use one of his rare metaphors, they are striking without being strained…. Maddocks [is] an exciting new talent…. His Nanticoke, like Margaret Laurence's Manawaka or David Adams Richards' Miramichi, [may one day] become a place with which all literate Canadians are, or at least should be, familiar.” –National Post

“Plain talk about plain people. That’s what Rick Maddocks delivers in this superb collection…. The detail is achingly accurate…. Told…with matter-of-fact intensity…. His prose is clean and lean and won’t let go of you once it grabs you. One of the best books of the year.” – NOW magazine

"[This] is a portrait of a strnage, often ugly place that is — disturbingly enough — also perfectly recognizable as Canadian…Folks are mostly unhappy in Nanticoke, but the lessons of the Sputnik Diner are interesting ones. Finally, it seems a shame to leave.” – Valerie Compton, Calgary Herald

“The quirky humour in Sputnik Diner…makes the book an enjoyable read…Maddocks’s attention to detail leaves a powerful impression upon the reader.” – Kingston Whig-Standard

“Rick Maddocks proves himself the master of the novella, on the first try…In Sputnik Diner, Rick Maddocks…create[s] a world that is satisfying, surprising and full.” – Annabel Lyon, Vancouver Sun

“[A] fine debut collection of short stories…the two things a young writer really needs are the two things that can’t be taught — curiosity and compassion. In his first book, Rick Maddocks proves he has plenty of both.” – Montreal Gazette

“[An] impressive talent…. Like Alice Munro, whose works share the common terrain of late-20th-century Ontario, Maddocks’ skill lies in turning out vivid and compelling characters. [His] detailed observations speak of a warm affection for the mess of family life and the rhythms of small town living.” – Quill & Quire

“Sputnik Diner is a bona fide gem – a deeply felt suite of short stories that chronicle a Welsh family’s dislocating arrival into the strange new world of a small Ontario town. Maddocks is a calmly lyrical talent.” – Vancouver Magazine

“Terrific…. Subtly portrayed…. Throughout Maddocks’s work, there are strong echoes of dirty-realist American writers like Tobias Wolff and Frederick Barthelme. Like them, he’s at his best when he keeps his writing lean and unsentimental…. Maddocks strikes [many] notes of grace throughout Sputnik Diner. While things don't turn out so well for the folks in Nanticoke, there's something beautiful in the way they fall out of the sky.” – The Globe and Mail

“Maddocks eschews showy writer’s tools, … relying instead on a painter's eye for detail and colour. The writing appeals to the reader's visual imagination and makes for effortless reading; there are times when Maddocks achieves that most prized of writing moments -- the transparent text, when the gap between reader and story seems to disappear. When Maddocks does use one of his rare metaphors, they are striking without being strained…. Maddocks [is] an exciting new talent…. His Nanticoke, like Margaret Laurence's Manawaka or David Adams Richards' Miramichi, [may one day] become a place with which all literate Canadians are, or at least should be, familiar.” –National Post

“Plain talk about plain people. That’s what Rick Maddocks delivers in this superb collection…. The detail is achingly accurate…. Told…with matter-of-fact intensity…. His prose is clean and lean and won’t let go of you once it grabs you. One of the best books of the year.” – NOW magazine

"[This] is a portrait of a strnage, often ugly place that is — disturbingly enough — also perfectly recognizable as Canadian…Folks are mostly unhappy in Nanticoke, but the lessons of the Sputnik Diner are interesting ones. Finally, it seems a shame to leave.” – Valerie Compton, Calgary Herald

“The quirky humour in Sputnik Diner…makes the book an enjoyable read…Maddocks’s attention to detail leaves a powerful impression upon the reader.” – Kingston Whig-Standard

“Rick Maddocks proves himself the master of the novella, on the first try…In Sputnik Diner, Rick Maddocks…create[s] a world that is satisfying, surprising and full.” – Annabel Lyon, Vancouver Sun

“[A] fine debut collection of short stories…the two things a young writer really needs are the two things that can’t be taught — curiosity and compassion. In his first book, Rick Maddocks proves he has plenty of both.” – Montreal Gazette