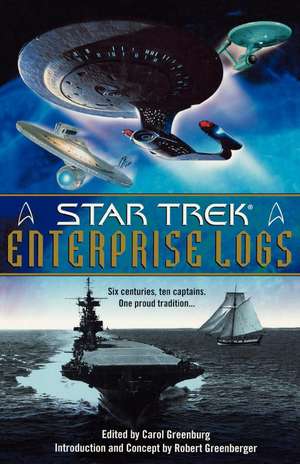

Star Trek: Enterprise Logs Anthology: Star Trek

Autor Carol Greenburgen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 iul 2000

Din seria Star Trek

-

Preț: 128.08 lei

Preț: 128.08 lei -

Preț: 116.47 lei

Preț: 116.47 lei -

Preț: 315.62 lei

Preț: 315.62 lei -

Preț: 138.52 lei

Preț: 138.52 lei -

Preț: 133.77 lei

Preț: 133.77 lei -

Preț: 126.39 lei

Preț: 126.39 lei -

Preț: 85.80 lei

Preț: 85.80 lei -

Preț: 93.78 lei

Preț: 93.78 lei -

Preț: 153.26 lei

Preț: 153.26 lei -

Preț: 73.72 lei

Preț: 73.72 lei -

Preț: 144.70 lei

Preț: 144.70 lei -

Preț: 111.57 lei

Preț: 111.57 lei -

Preț: 99.55 lei

Preț: 99.55 lei -

Preț: 103.24 lei

Preț: 103.24 lei -

Preț: 243.20 lei

Preț: 243.20 lei -

Preț: 85.32 lei

Preț: 85.32 lei -

Preț: 126.33 lei

Preț: 126.33 lei -

Preț: 178.56 lei

Preț: 178.56 lei -

Preț: 281.51 lei

Preț: 281.51 lei -

Preț: 36.78 lei

Preț: 36.78 lei - 39%

Preț: 40.96 lei

Preț: 40.96 lei - 41%

Preț: 40.85 lei

Preț: 40.85 lei -

Preț: 126.61 lei

Preț: 126.61 lei -

Preț: 148.49 lei

Preț: 148.49 lei - 43%

Preț: 54.44 lei

Preț: 54.44 lei - 19%

Preț: 52.28 lei

Preț: 52.28 lei - 18%

Preț: 53.28 lei

Preț: 53.28 lei -

Preț: 167.96 lei

Preț: 167.96 lei -

Preț: 153.48 lei

Preț: 153.48 lei -

Preț: 150.78 lei

Preț: 150.78 lei -

Preț: 192.14 lei

Preț: 192.14 lei -

Preț: 215.55 lei

Preț: 215.55 lei -

Preț: 92.27 lei

Preț: 92.27 lei -

Preț: 93.59 lei

Preț: 93.59 lei - 25%

Preț: 33.67 lei

Preț: 33.67 lei - 37%

Preț: 42.70 lei

Preț: 42.70 lei - 37%

Preț: 42.36 lei

Preț: 42.36 lei - 36%

Preț: 43.62 lei

Preț: 43.62 lei

Preț: 120.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.05€ • 25.03$ • 19.36£

23.05€ • 25.03$ • 19.36£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780671035792

ISBN-10: 0671035797

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Pocket Books/Star Trek

Seria Star Trek

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0671035797

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Pocket Books/Star Trek

Seria Star Trek

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Carol Greenburg has edited a number of Star Trek bestsellers, including the Star Trek: Enterprise Logs anthology.

Extras

Chapter One: Captain Israel Daniel Dickenson

The Sloop-of-War Enterprise

"In every revolution, there's one man with a vision...."

Captain James T. Kirk, Star Trek

Diane Carey

Diane knows a little more than most of her colleagues about ships and the rigors of command. In addition to being an accomplished author of science fiction and historical fiction, she is also a seafaring type, preferring older vessels. In fact, Diane braved the lash of early winter, crewing aboard the 1893 Schooner Lettie G. Howard and arriving at New York City's docks. She stopped rigging and cooking just long enough to complete the following story.

This summer, Diane adds her own vision to the Star Trek universe with a new series of novels, starting with Wagon Train to the Stars and introducing one and all to the U.S.S. Challenger.

Diane's contributions to Star Trek extend back more than a decade, including the giant novel Final Frontier, which gave readers a glimpse at George Kirk, father to James. She has written six Original Series novels, four novels set during The Next Generation (including the first original story), six adaptations and one original Deep Space Nine story, and two Voyager novelizations.

With her husband, Greg Brodeur, Diane continues to whip up exciting stories, and shrewd readers will detect the loving attention paid to the starships, making them vital characters along with their crew.

Diane adds:

Special thanks to Captain Austin Becker and the Sloop-of-war Providence of Rhode Island, replica of John Paul Jones's fighting ship, for their help and good works in preserving Revolutionary War history.

My admiration and gratitude also go to Captain Erick Tichonuk, First Mate Len Ruth, and all the crew at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum of Basin Harbor, Vermont, for their hospitality and advice, and their faithful tending of the replica Gunboat Philadelphia. The original Philadelphia resides at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Another of Benedict Arnold's gunboats, believed to be the Spitfire, has recently been found at the bottom of Lake Champlain. As a sailor of historic ships, I convey my applause to the team recovering this national treasure, and hope she soon rises to receive the tribute she deserves.

The Veil at Valcour

"Are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties?"

Benedict Arnold, 1775

Dawn, October 11, 1776

"That's the signal gun! Row for it, men! Royal Navy in sight! Heave! Heave!"

Frosted orange leaves roared across the chop. Wind snatched away the coxun's orders. Beneath me a dirty bateau clawed upward, punching through whitecaps against a bitter wind. An hour ago the wind had been at my back. Now, scratching down the Adirondack hemlocks and spruces, it chipped at my nose and cheeks and froze the moisture in my eyes.

"How near are we? Will we see the Continental Navy soon?"

"Heave! Few minutes. Hard over, larboard! Heave!"

rd

Black lake, black land -- the large double-ended bateau muscled up on its right side as if hauled by a winch! I let out a strangled shout and became intimate with the gnawing water at my left elbow. Everything was so black, so dark, that I entertained a brief crazed fear that the men in this boat were the only Americans here and we would face the British ships all alone.

The coxun's fingers dug at my collar as he pulled me back to my seat. "Keep a grip on them fascines there, your honor."

"What happened?"

"Tiller's over. We're coming into the strait."

"It's the devil's own dark! How could you know to turn?"

"Wind dropped. We're in the lee of Valcour Island. We'll meet up with the American navy any minute."

While the boat hurled itself vertical on the unhappy chop, then skated sickeningly downward, I sat upon a prickle of hardwood saplings, twice as long as I was tall, stripped of every branch and tightly bound into nine- or ten-inch bundles so that they were almost tree trunks again. Five of these bundles, a great weight indeed at nearly two hundred pounds each, were strapped across the bateau's wide beam, and caused the boat to wobble and struggle horridly. Along with those, piles of evergreen boughs with warty bark and needles assaulted my legs with every shiver. What could a navy want with trees?

I strained to see into the darkness, but might as well have had a mask over my eyes. The shore of New York, on our left until now, remained invisible. Around us, Lake Champlain was deeply cloaked.

Then, out of the night, came a voice blasting on the wind. "Hands to the tops'l sheets and braces! Bring the tops'l yard abeam! Don't worry, boys, we possess the caution of youth! Other words, none!"

A huge dark mass surged out of the night, angling over my head as if I'd stepped onto a porch. Swinging in a wide arch came a thirty-foot wooden spear with four enormous triangular sails lancing the sky like great teeth. A ship's bowsprit, inches away!

"Oh!" I dropped back and kissed the water again.

Moonless night had hidden an entire ship!

The ship's sides were mounted with bundles of cut evergreens, a shaggy fence making the vessel into a giant bottlebrush. What an otherworldly sight! Camouflage?

"Hard over, Henry!" the voice again came as our bateau rowed abreast of the massive shuddering object. If the boat and the ship came together on the same wave, we'd be crushed. "Port brace, haul away! Lavengood, Thorsby, Barrette, man the bunts and clews. LaMay, show them the lines, quick, man! Barclay and Rochon, lend Hardie a hand! McCrae, your brace is fouled in the spruces. Don't hurt your hands. McCrae, do you hear me? Stephen!"

Black hull planks bumped the bateau. Bracketing his mouth, the coxun shouted up. "On deck! Heave us a painter!"

High above, a wall of angular gray sail snapped in anger. Then, flap, flap...crack! -- the wind filled it! The ship heeled hard, bit the water, and leaped beyond us.

"Sheet her in and stand by! Larboard, slack your sheet! Clew the tops'l! McCrae, what do you think you're doing? Rochon, I said stand by on that sheet!"

That wind-muffled voice -- did I recognize it? Or was it wishfulness after three cargo boats and two fishing smacks?

Just above me, a lantern flickered to life, dancing on the night. Its fiendish glow changed everything. Hemp ropes veined a hundred feet into the sky. Two great wooden strakes carried a huge sail that swung like a swan's wing.

From an unseen hand, a rope snaked out to the bateau, falling a foot from me. The coxun snatched it up, and twisted it to a cleat, and thus we wheeled sidewise toward the surging wooden wall.

"Is this the right ship?" I called. "I'm seeking Israel Daniel Dickenson, aboard the Betsy. Or is it the George? I've got conflicting information on the ship's name."

"We don't call our ships that way." The coxun grasped a spruce bow fixed to the ship and with superhuman power dragged the bateau close, and we skated an inch from disaster. "Get up there, man, before we're beat to splinters!"

As the bateau heaved upward, I stood and put one foot on the bateau's rail. "I'll break my neck!"

"Jump!" the coxun bellowed, "or you'll have seventy ton of sloop in your gullet!"

With one toe I pushed upward, hands scratching for a grip. Boughs rustled, my cloak and tricorn hat disappeared, and I was carried up and away, a fly clinging to a mule's black belly!

"Fend off!" the coxun called. Oars blunted the ship's sides. The boat roached away.

"Heaven help me!" With me riding her wet flank, the ship clawed forward and defied New York's western shore with her long bowsprit. Over me the hostile sail whistled. Above it, a smaller square sail crawled into a bundle and screamed on its yards. I saw all this in an instant -- lines snapped, blocks creaked, water sprayed, boughs whipped, and the yard squawked like an enraged pelican trying to snap me up.

Again, that voice. "Hands to the larboard side, for God's sake!"

A force grabbed me from above. I lost my legs. My body went straight outward on the wind. Headfirst I plunged through the bundled branches and flopped face-first upon a tilted deck. Pressing my hands to the planks, I twisted to look up.

Above me, a narrow man-shaped shadow loomed. "Get those fascines over to Philadelphia and mounted on. Should've been well done by midnight. Give them to Blake, he's the mate. Or Captain Rue himself. Tell them to rig their canopy and hurry! The wind's from the north!"

I rolled over and choked, "Daniel! Thank Heaven!"

The shadow's shoulders lowered some, arms out at his sides. His head tipped forward. Against the bleak sky, shoulder-length unbound hair flew wildly. "Adam Ghent, that's not you on my deck."

He offered no hand to help me up. His unglazed anger was visible even in the dark.

But wait -- the sky had lightened. As I drew to my feet and braced my legs, I could make out men around me doing feverish work, sawing, tying, hauling lines in a clutter of iron tools, round shot, wadding, tackles, blocks, piles of rope, and sponge rammers. A boy of about ten years used a bellows to keep a stone hearth glowing inside a formation of bricks. There were no uniforms. The men wore anything from muslin to buckskin, some with wool vests and tricorns or any manner of hat they could construct, and buff or black breeches. They didn't look like a navy.

I stood upon a deck that took up the front half of the ship. On my left was a snarly-looking black cannon. On my right stood a set of ladder steps leading up to another deck, a higher one, which scooped back to the stern. I could just make out more men up there, minding a huge tiller.

Through the shaggy fence of branches, I saw another ship on the water, almost as large as this one, with two quill-shaped yards jabbing the sky. Massive parallelograms of canvas carried her into a crescent of anchored vessels, a line of ghosts on a moorside vigil. All the boats wore beards made of bundled saplings.

"Who's that?" I pointed at the other sailing vessel.

"The Galley Washington," Daniel answered brusquely, "moving into defensive position. Lavengood, sheet in all you can get. By the saints, if we're not up another point! Good ship!"

To our right was the crescent of anchored vessels, the smaller ones with one mast each, the larger ones, others like the Washington, with two. "What are all these boats?"

Daniel flopped an arm against his thigh. "Why, this, brother, is the Continental Navy! Eight fifty-four foot gunboats, a cutter, two schooners, three galleys, and the sloop you're on. And sad you'll be ever to have laid eyes upon it."

"Why are they anchored? You're not meaning to have a battle this way -- "

"The gunboats are flat-bottomed and square-rigged. They can't hope to maneuver upwind. We'll fight at anchor."

The sloop heeled fiercely and passed the ship called Trumbull, heading northwest, away from the place where we should be anchored.

"We'll be nicking Revenge's sprit at this pace," a man at the tiller commented. He had a black bandana tied onto his russet hair and arms like tree limbs, and he used lines to control the heavy tiller with tackles.

"We'll make anchor with one more tack," Daniel said to him, "and come to our position on the broad reach."

"It'll have to be handy."

"Say it again, Henry, that the Fates hear you over the wind."

In defiance the wind screamed away his words. We cut past four of the gunboats, with their single masts drawing circles on the sky, sails bundled upon slanted yards. At the south of the bay, another sailing ship maneuvered in the cup of the crescent. "Who's that one?" I asked.

"Royal Savage. Quiet, Adam. Ready about! Keep a firm turn on the pins, men. Let's not have a repeat of that ugly little episode yesterday. Let go your jib sheets! Helm over, Henry!"

At the tiller, Henry and two other men suddenly shifted from one side of the ship to the other. Only now, as their cold-reddened toes squeaked on the wet deck, did I realize they were bare of foot. Some had tied cloth about their feet, but these men were wearing rags.

The ship's narrow body shuddered, came to an even keel, rocked briefly on the chop. The long bowsprit bit into the north wind.

"Starboard, haul away your jib sheets!"

The crew's heads disappeared and their elbows pummeled the air. The four triangular sails on the bowsprit whacked like wild horses, making a drumming sound, but the bow came around. The ship turned on a pin, the sails snapped full, and instantly we were faced back east, stabbing the bowsprit at Valcour Island.

"Prepare to haul that gaff down by hand," Daniel ordered. "The sail'll fight you. Hands to the cathead!" When some men looked confused, he added, "Show 'em, Henry. Barrette, man the aft anchor. Men, it's critical both anchors drop at the same time, understood?"

The man called Barrette smiled ruggedly and said, "I can forge 'em, Daniel. Bet I can drop 'em too!"

"Good man," Daniel said. "Otherwise we'll end up with our stern swung south. We must be broadside to the enemy. We're passing Connecticut -- as we come abeam of New York, we'll strike sail and drop anchor. Almost there...wait...wait...ready...aft anchor, drop! Take in and make fast -- quick, quick! Peak and throat halyards, lower away! Forward anchor, drop! Downhauls, haul away!"

I had only half a clue what he was up to, but the ship seemed to know. The big sail and the triangles fell into linenfolds, iron rings screaming on the cables, and the wind raced by without us. The anchor lines snapped with us between them. We were anchored in position, with a galley before us and the crescent of other boats behind, strapped across the bay between Valcour Island and the shoreline of New York.

Daniel faced his crew down on the gun deck. "Cockbill the tops'l yard. Clear for action, boys, ready every gun. Get that canopy up and the pine boughs on top of it! Get it over the forward guns if you can. Handily now! Wind's from the north!"

Around us, shivering, the men scratched to their work.

Eyes ferocious, lips flat, Daniel Dickenson finally turned to give me the attention he had avoided. "Come for last rites?"

"I brought a parcel from your mother." Rather clumsily, I climbed the nearly vertical steps, holding ropes that were fastened in the fashion of a handrail. Still Daniel had to clasp my arm and pull me to the upper deck. Bracing my legs, I fished through my coat, hoping the ride upon the ship's flank had not claimed the bundle. Good, here it was.

He did not take it. "You came from Connecticut to bring mail?"

My brother-in-law leered at me through a flop of brown hair beating his cheekbone. I scarcely recognized him. Four months ago he had gone to answer the call for experienced sailors and wrights, rosy-cheeked and well-clothed, umber hair bound at the back of his neck like a gentleman. The wraith before me was gaunt, waistcoat ratty, breeches patched, day coat completely missing. His hair was long and lusterless, gone dark as oak bark. Scratched, bare arms protruded from torn sleeves as if someone had dressed a cadaver. Upon his feet were Indian moccasins, worn to parchment.

"What happened to you?" I whispered.

"Camp fever," he said. "Typhoid, malaria, and four months round-the-clock toil to construct these gunboats and galleys, launching a new vessel by the week."

"Where are the riding boots I gave you? And the white linen shirt Eloise made?"

"Traded the boots to Indians for cornmeal in August. The shirt was burned off at the blacksmith's forge making the anchors. Glad I am to have this brown hunting shirt and waistcoat."

He stopped talking as two men came to his sides, one being the man from the tiller called Henry. They were the only two men not rushing to some task of preparation.

"First mate Henry Hardie," Daniel began, "and Doctor Stephen McCrae. My wife's brother, the parson Adam Ghent. What he's doing here is a mystery."

I bowed low, and would've tipped my tricorn if I'd still had it after my little ride. "Every navy needs a chaplain. I'm here to lead morning prayers."

"We only have one morning left," Daniel said cryptically.

The two other men said nothing. I knew how I must appear to them, with my blue wool coat and white neckerchief stuck with crumpled autumn leaves and pine needles, windburn russeting my thin ivory face, blond hair blowing into my eyes. Daniel had always likened me to a parakeet, his height but a third less his weight. Today, braced on many sides by the frosted Adirondacks, we stood on the deck of a fighting ship in a very strange equity, surrounded by fifty half-frozen carpenters, shipwrights, sailmakers, ropeworkers, ironsmiths, powderboys, and militiamen, and not one to bring me tea or buff my buckles.

"What is this boat we're on?" I peered up at the hundred feet of single mast. "Did you build this too?"

Henry Hardie tightened his folded arms. Under his black bandana, one eye tended to squint. "She's a Canadian provincial sloop they used to guard the lake for the redcoats. The General went and captured her from the British at St. John's last May."

"All of five years old," McCrae added, "and she's the grand dame of our fleet. Until today, she was the biggest ship on Lake Champlain."

"What's different about today?"

"Wind's from the north," Daniel blurted.

There was that phrase again. What could that mean? But instead, I asked, "Is this the George? I've heard several names."

"The General doesn't name our ships after people, like the King's admirals do. She's a Yankee sloop now."

"But I saw a 'sloop' on an embroidery once. It had three masts."

Hardie shifted his cold feet. "The British call any ship a sloop which has a single gun deck. Three masts is 'ship-rigged.' This girl's a 'sloop rig.' One mast."

"Congratulations, Adam," Daniel snarled. "You now know more about sailing ships than most of these men here."

"Come now," I shivered. "What should we call her, then? And shouldn't I present myself to the captain while we rest at our anchorage?" I made a little practice bow at the waist.

Behind Daniel, Hardie cocked a hip. The man called McCrae smirked ironically.

Daniel hung his arm around the gigantic folded sail with its two wooden strakes spearing back beyond the stern into the night. "This is the Sloop-of-war Enterprise. I'm captain. And this isn't an anchorage. It's a coffin."

Directly in front of the anchored sloop, the hogbacked scrub brush of Valcour Island wrecked the wind that raked down her spine, causing unearthly chop in the bay. While at anchor, we climbed down to the gun deck to get out of the frigid wind. Men around us began to huddle beside the sloop's twelve four-pounder cannons. Wordlessly they stacked hand-chilling iron balls upon shot racks.

Out there, on the bay, the line of little ships clinked and wobbled, held in place by a complex of cables and anchors. On a few of the ships, like this one, men were mounting canvas canopies and thatching them with evergreen boughs, releasing a Christmastime aroma through the pitch and black powder.

So this was the Continental Navy. What a thin line indeed we made.

Bracketed by his two friends, Daniel glared at me. "I charged you to stay in New Haven and take care of mother and Eloise."

"I'm caring for Eloise best I know how -- by making sure her husband comes home safe. As for your mother, she takes care of herself."

I held out the bundle of burlap from Daniel's mother, no bigger than a holiday pudding, tied with twine, sealed by a dot of candlewax with a shank of cat hair pressed into it. Still he did not collect it.

"There she is," he commented dryly. "Hello, Mother."

"Let's open it, then." McCrae reached for the parcel.

Daniel slapped his hand down. "Are you mad? You've no idea what might crawl out of that."

"Get him, Henry."

At McCrae's order, Henry Hardie scooped Daniel's elbows from behind and dragged him backward while McCrae snatched the parcel from my hands.

"Here now!" Daniel bellowed. "This is serious! The Royal Navy's been spotted! We must prepare to receive them!"

Two more men, whom I would come to know as Lavengood and Thorsby, sprang to hold Daniel back while his possessions were pillaged. I was surprised at their insubordination. This was nothing like the stiffly proprietous British soldiers patrolling the Colonies. Especially the impudent young doctor -- he surprised me.

"Won't take a moment." McCrae cut the string with a copper knife. On top of a cannon the parcel unfolded itself, spilling an odd collection of candles, twigs, dried flowers, and a fist-sized bag made of animal skin and stuffed full, dangling from a leather thong. "What's this bag?"

"It's called a crane bag," I explained. "Daniel's mother is somewhat of a -- an apothecary."

"Doesn't smell like medicine." McCrae let Hardie smell it too, then the big bearded man named Rochon.

"She told me it's purifying incense," I explained. "Cedar, sandalwood, sage, rose oil, and salt is what she mentioned."

Rochon looked at Daniel. "Why would your mother send that?"

"Because she knows lake water stinks. Put that away!"

"Where did she find a crane to skin?"

"It's probably some poor quail she slaughtered. All of you, this is folly. There's a battle coming!"

Unbelievably, the crowd around the flap of burlap was growing rather than shrinking. Struck me that, for these men, there'd been a battle coming for months and they hadn't the energy to believe the moment had finally arrived. The distraction of a parcel from home, anyone's home, was too magnetic not to give it a minute or two of what little they could spare.

"Look at the tiny bell," Hardie said, pointing at the clutter now revealing itself. "And a black candle."

"And a green one," McCrae noted. "Does the color mean something?"

When Daniel wouldn't answer, I did. "She said that in olden times bells were rung to bless the souls of the dead."

Lavengood's face snapped up. "Does that mean she thinks we'll die?"

"No!" Daniel bellowed. "Pity's sake, Adam!"

"What's it mean, then?" Thorsby asked.

Daniel hesitated, shifted, and was finally released by the men holding him. Sagging, he admitted, "All right, well, it asks the favor of those on the other side of the Veil."

"What veil?" Hardie demanded.

"The Veil. Between this world and the other. It's a superstitious woman's folly! You can tell by the ingredients she's living in a dream!"

"Can you?" McCrae opened the crane bag and, shielding it with one hand, spilled the contents onto the frame of the cannon truck. "Here's blue flower."

"Monk's Hood," Daniel fumed. "Just a plant in her garden!"

"What about these others?" McCrae asked.

"She embarrassed me all my childhood with her nonsense!"

rd

Hardie peered curiously. "What can it hurt to tell us, Daniel?"

A flash of empathy raced through Daniel's dark eyes at the men's hunger for distraction. Making a grumble in the bottom of his throat, he took a step closer, but did not touch the contents of the little pile, as we all used our bodies to made a windblock to keep the bits from blowing away.

"Nightshade," he reluctantly began, "dried white rose...devilvine and foxglove -- there, you see how silly she is? All this is from her moonlight garden. It's coming into morning! The battle will occur in broad daylight."

"Could she have an idea about the night?" I asked. "Perhaps your enemy fleet will arrive after dark."

He threw his arms wide. "Feel that wind? They've got it at their sterns! They'll be here any time. She had no idea I would engage the British at all, yet she sends me a bag of moon-ruled herbs. Once the enemy fleet passes south of the bay mouth, Royal Savage will go out and lure the British upwind into Valcour Bay and we will fight under a cold noon sun, if, with God's grace, they don't already know where we are and try to come in from the northern strait. Either way, we fight under the sun. So much for the moon."

McCrae held up a sprig. "Is this a moon flower too? And pinecones and acorns. What's this one?"

"Dried apple. Cedar, hemlock, rowan -- tree magic! She's sent the whole forest! And here I am on the water!"

"Here's a stone," Hardie pointed out. "White one."

"Moonstone," I told him. "She said it was for rising above trouble. The St. John's wort is for invincibility. The thistle and staghorn are for protection too."

"We'll take it," LaMay sputtered. The other men grumbled an ironic laugh.

I turned to Daniel. "What does it all mean when it's put together? You might as well tell us, for the entertainment value."

The men nodded and rumbled encouragements.

Spearing me with a terrible glower, Daniel shifted his weight on the bucking deck. "Uch, all right....It's a charm of concealment."

The men seemed to like that. Daniel seemed to hate it.

"She said she wanted to make a flying potion," I told him, "but that you always refused it before."

He pressed one hand to his forehead. "It's not that you fly, my friend, it's that you think you fly." He clapped his hands once, sharply. "Men, get to your guns! Load up! Grease the trucks! Pile the shot on the starboard racks. The enemy's been spotted, save your souls! Get cracking before we freeze in place!"

The men splintered off. Daniel stomped down the deck, scooped up a line, and began to coil it. I was left shivering in the waist of the sloop. Around me the ship creaked and rolled upon the bay's chop. Above, the morning sky lightened, but an ugly light.

After gathering up the crane bag, candles, bell, and the other contents of the burlap bag, I waddled after him. "Daniel, it's injudicious of you to scoff at your mother this way."

"In what manner should I do it, then?"

"Don't be cranky. These fears aren't trivial for her. She's told me she's had them since the day you were born. Please pay them some attention, for my sake? I've come so far."

"You entertain too easily a woman's fears."

"But what is the symbolic message of these things she sent? I'd like to know, in a professional capa -- "

"You're a chapel minister! Why would you care what a thistle means to a pagan?"

"She says this is a critical time for you. She read signs -- "

"Signs?" He slammed the coiled line to the deck and started stacking round shot. "Birds flying backward? Water running uphill? Butterfly eggs turning black? Do you see that schooner out there? They've just spotted our enemy. I have reality to deal with."

Pausing, I changed my tone of voice. "I came also because of signs I've seen myself. Daniel, I grieve to tell you...George Washington has evacuated Long Island and New York."

A shot slipped from his hand and thumped hard to the hollow wood. It rolled away. Daniel was suddenly still. So were many men within sound of our voices. The change was sobering.

He did not look at me, but gripped a swivelgun on the ship's rail as if to steady himself. "That's...grim news, brother."

Nearby, Hardie pulled his bandana lower on his forehead. "It means we could be caught between an advancing army either from Canada or also up the Hudson."

Apparently I had put a crushing burden upon my brother-in-law. Daniel pressed his hands to the swivelgun and closed his sunken eyes. "Then we must not go ashore. If our ships sink, we must sink with them. Henry, send LaMay in a boat to the Congress. Tell the general."

Hardie swirled off, snapping orders to some other men.

Daniel straightened, suddenly aged. He gripped the rough-cut branches that were bound to the sides of the sloop and gazed at the southerly mouth of Valcour Bay. There another ship, a schooner, was fighting for control of the wind as she exited the bay. Royal Savage, he had called it. I wondered why a Colonial ship had an English name, but decided not to ask.

"You shouldn't have come, Adam," Daniel uttered. "You've boarded a dead ship, in company of a dead crew."

I shrugged. "God will be with me."

"You'll only be distracting him from the rest of us. We're set to stew in this freshwater cauldron." He drew a ragged breath. "This morning smells of winter. Midnight's necromance never wicked off. And we possess only the water now....Pray we hold it."

"Oh, there's more than water here," I pointed out, trying to lighten his mood.

He looked at me. "What do you mean?"

I fingered the bare-wood fascines flanking the sloop's rail, sticking high into the air like fortress walls. "Earth," I said. As the cold breeze snatched at the branches, I brushed them. "Wind. Water, obviously...and fire." I patted the stone-cold body of the swivelgun. "The four natural elements of power your mother speaks about."

He shook his head in dismissal. "Mother visits again. I wish you'd left her home, Adam."

"Daniel!" Hardie called. "Congress is headed back to position. General's boat's coming alongside."

"Oh!" I cried. "May I meet him? I've heard all about him!"

White stockings aflash, I scrambled after Daniel as he descended the steep ladder to the lower deck. A rowboat, smaller than the bateau I had occupied, drew up to the ship's side. In it were two oarsmen and an officer in a Colonial blue coat and tricorn.

"General!" I called. "Honor to meet you, sir! May I shake your hand?"

0 Hawk-eyed and hawk-nosed, black of hair and burly with residual power in his shoulders and hands, the general was a robust man of about thirty-five years, with burning blue eyes. He scowled up at me and Daniel from beneath his tricorn hat. "Who are you?"

"Parson Adam Ghent," Daniel grumbled. "My wife's brother."

"You haven't just arrived, Reverend, in the middle of mayhem?"

"I have, sir. And pleased I am to congratulate you for your conquest of Fort Ticonderoga! Everyone in New Haven is proud of its native son!"

The general grimaced. "Mmm, seems to have slipped the notice of the Continental Congress somehow. Why have you come?"

"To bring a parcel from Daniel's mother, and the unwritten love of my sister. His mother has some requests of him."

"You must pause to pay your mother attention, Dickenson," the general said right away. "But listen first -- our enemy is hull up on the northern water. The Royal Navy has toted a two-hundred tonner across the land in pieces and reassembled it. A full-rigger, twenty-four pounder cannons. Our scouts on the Revenge report counting no less than twenty-four gunboats, a radeau gun barge, and a goodly number of Indians in canoes. That's three times what I expected, all crewed by able seamen, commanded by Royal Navy officers. Us, we have a wretched crew of green ships and green men who don't know a halyard from a garter snake. Waterbury wants us to retreat. I've come to tell you and every captain that I have no intention of retreat, not before we've even touched off a gun. Why does he think I built this fleet? This north wind is our advantage. We must be clever!"

Henry Hardie leaned through the branches. "We could up anchor and run out suth'erd of them while we have the chance, perhaps engage them under sail as we run toward Ticonderoga."

"We can't outsail the Royal Navy on open water," Daniel told him. "Quarters in this bay are tight. Their mastery of the sea will serve less in a pond. We're small targets, we have that on our side. And, bless it, the weather gauge."

"I thank you for your support, Captain," the general said. "It is our plan that the Royal Savage should lure the British ships south of the bay before the British discover we're hiding here. I hoped they'll recognize her as one of their own which was captured, and it might make them lose reason and pursue. Then, being a schooner, the Savage will be able to pinch back up and join us while the British fall south."

The general turned, almost wistfully, and looked at the narrow strait leading out to Lake Champlain.

"That's my hope," he added, "but hope must be braced with spirit. We must show 'em here and now what we're built of. The British don't think we have the mettle to be a nation. They don't think we'll fight. We're Colonists in a fleet of rowboats, but the King's navy would not face us until they had their two-hundred tonner ready to sail. They dallied an extra month to ready that ship. So who is afraid to fight? It comes down to their pride against our stubbornness. Today is the day we will make England understand we mean to be a nation independent. This is it, my friends -- the United States Navy's first engagement! May we prevail! Bless you all!"

With a snapping motion, he gave the order to shove off. The rowboat lurched away on a rising wave.

Daniel watched them go. His expression told nothing.

I clapped a hand to my chest. "My goodness, he is infectious! Did you see those eyes?"

d"If we have a navy," Daniel said, "that man built it. He's the one who warned that the British could use Canada as a platform from which to strike at us. He predicted Lake Champlain might be used by the enemy to stab downward from the Richelieu River into the heart of the Colonies and split us apart. That would've been the end, before we even had a beginning. He was the only one who saw it, and he has knocked together this little fleet in a matter of weeks, to defend the lake today."

Leaning sideward against the fascines, Daniel gazed after the tiny rowboat wretching away from us, heading westward toward the gunboat New York. He watched the man in the tricorn hat.

"He has some tyrannical ways and suffers indignity poorly, but if I stay, it is only because of him. If I fight, it is because he showed me why. If the United States are ever to become a nation, it will be due to the mighty spirit of General Benedict Arnold."

"There they are!"

The wind off Valcour was unsteady, causing not swells but an unhelpful chop. A diabolical presence appeared at the mouth of the bay -- a honeycomb of English gunboats struggling under sail, coming two by two and three by three, and then bigger ships with sails puffed full, yards swinging as they tried to turn. All these, all at once, attempted to claw into the bay against the wind.

I snatched Daniel by the arm. "How can I help?"

"It's too late to train you to a gun. Help McCrae."

"What's his work?"

"Stephen is the only doctor in the fleet. Enterprise is the medical ship. You thought I was making a joke about last -- "

From the trees on the island came an unexpected pop, and two seconds later the fascine next to my shoulder shook. Mauled by splinters and needles, I staggered on the bucking deck and fell to my knees, my mouth full of wood spray. What had knocked me down?

"Adam!" Daniel scooped me up and checked for blood, but my only injuries were scratches.

"Indians!" Henry Hardie pointed onto the high cliffs of Valcour Island. "They've landed Indian snipers on the island with muskets! Keep your heads down, men!"

Daniel swung around. "Lavengood, take the forward swivelgun to 'em. Lather 'em with grape!"

Now I understood the bound saplings made fast to the ship's sides, and the canopy layered with pine boughs. Beside me, the fascines stood firm, except the very top of one was now partly shredded. That musket shot would've happily cut through my chest, but instead sheared across the top of the fascine. All that had struck me was the concussion and some splinters.

"Look!" I pointed at the mouth of the bay, where I saw a huge cloud of square white sails.

"That's their full-rigger," Daniel said, still holding onto me in some kind of possessed preoccupation. "Inflexible. She'll have sixteen or eighteen twelve-pounders. Each of our gunboats only has one twelve. If she comes up, she will annihilate us."

Though we held our breaths, the big ship moved sideways against the wind, scuttling farther south, never turning toward us. Back and forth it tacked with obvious effort, courting the mouth of the bay but never coming in.

"They're stuck downwind!" Daniel gasped. "Bless the wind!"

As the men cheered, Rochon pointed at another lick of sail just barely showing through the mouth of the bay, struggling on Lake Champlain. "Their gun raft can't come back up either! Their biggest ships are stuck down!"

"The lake's too narrow for ships that size. They haven't tacking room. Good thing -- we're hopeless of counterbalancing the presence of a two-hundred tonner. She might be even more, by the look of her. Might be three hundred, war loaded."

I saw the truth in Daniel's eyes, that sinking and desperate awareness of complete overwhelm. As the British ships came and came and kept coming, we gradually swallowed the terrible spoonful -- we were inferior in almost every way, insufficient against the numbers and quality of both ships and seamen. We faced trained officers who thought themselves our ruling class, who had the privilege of a king's navy to command. They possessed the whip hand. We were but Colonial thimbles bobbing purposefully on the white chop.

Rochon blew on a guttering linstock to keep it lit. "Here comes a schooner. What's its name?"

"The Carleton, I think," Daniel said, "if our scouts got it right. Do they mean to take us on alone?"

"I can see her guns. Look like sixes to me."

"Let's make our fours speak well to them. Fire at will, Joe!"

"Welcome to America, Carleton." Rochon's burly body took a single step forward. "Fire in the hole!"

Some of the men had the sense to block their ears. Sadly, I was not one of these. Again I was jarred to my knees, this time by the sheer stupendous noise. Never had I heard such a noise, and I was once nearly struck by lightning! A second later, the tremendous boom echoed off the rocks of Valcour Island and assaulted us a second time.

Around me, many men were huddled in shock. They apparently hadn't heard a loaded cannon go off either, nor had they smothered in the gassy cloud of gun smoke.

"Get up!" Daniel raged. "Load, aim, and fire! Worm and swab and do it again! Doubleshot ball and canister! We're not here to save ourselves! Give me that schooner's rigging for breakfast!"

His conviction drove away our terror and charged every man. Better get used to it. I stumbled up.

Scarce a second later, head-splitting cannon blasts rang from all the other Colonial ships, and the brawl was on.

The Schooner Carleton was the only English ship that got anywhere near us. It now began a savage response. Hot shot bounded through the air. Their first ball struck the Gunboat Philadelphia right in the middle of her canopy, ripping most of it away. Then a full broadside brutalized many more of our ships. In minutes Valcour Bay was shrouded in acrid smoke.

But the wind was from the north. Bless the wind -- the Crown's big ships, which they had carted from the St. Lawrence, were useless to maneuver up the narrow strait at the mouth of Valcour Bay. Finally, in a tantrum of sheer muscle, the twenty or more British gunboats dropped their sails and rowed themselves into a raggedy string across the bay behind the Carleton, manned by feral sailors ashamed that they had to row. Once in position, they tore into us. The inhumanity began in earnest.

Fiendish with desperation, we returned savagery for savagery. There were no calls for heads down, take care, step cannily, no concern for the injuries or death being suffered. Something completely else was at work. These men were willing to lose limb and life. Half-frozen all night and now sweat-greased under cannonfire, they cared nothing for their comfort. They were fighting not to live, but to live in liberty. It made all the difference.

The casualties began to arrive almost immediately, ferried in rowboats heaped with bloody moaning bodies. I did what I could, hauling the wounded aboard, giving a shot of rum, holding them down while a grim Stephen McCrae took his capital knife, saw, curved hooks, and ligatures to their bones, flesh, arteries, veins, ligaments...then it was my job to cauterize the wounds with hot tar -- if time allowed. The first one made me ill. The fifth made me cold. Over the side went arm after leg after foot after hand, until the shot-dimpled water around us ran red, decorated with a piteous stew.

And then, a boy of seventeen heaved back and died in my arms while his leg was being cut off. At first, I didn't realize he was gone. In the middle of my prayer, McCrae pressed his hand to mine and said, "He's done for this world, Parson. Put him overboard."

Somehow I was efficient about it. I heaved the corpse headfirst into the bubbling water. "God be with you, fellow."

This was the first day in my life I had ever put my hand on the dead. What it did to me, I cannot describe, except that in a few hours' time I went from a country minister flinching at a muzzleloader's pop to a flint-hearted veteran unaffected by the blare of a cannon two steps from me. Hundreds of howling Indians peppered us with musketshot, but I soon learned to trust Benedict Arnold's wooden barriers. Though mangled friends writhed all about me, I can only say my mind began to shut down. My hands worked independently of thought. My brain dully registered the shouts of Daniel and Hardie, the only two seasoned sailors aboard, helping the other men to aim the cannons to some effect.

Though my head was mostly down to my work, I registered the progress of the battle through individual cries that made it from ear to brain through the cannons' crash....

"Royal Savage is aground on Valcour! They're abandoning ship! Send a boat for them before those Indians kill them all!"

"Look at Arnold running about aiming the guns on Congress himself. I wish I had his guff."

"He's the only one aboard who knows how."

"They've boarded Royal Savage. They're turning our own guns on us. Thorsby, train the tackles on the forward gun to fire on them."

"I rerigged the Savage with my own hands."

"She's not ours anymore."

"Quoin that gun down, LaMay! You're overshooting! Go for the Carleton's rigging!"

"Men, watch yourselves! Their grape is cutting straight through the fascines!"

"What's that explosion?"

"Gunboat! We hit the ammunition locker!"

"Great Lord Almighty..."

"Carleton's cable spring's shot away! She can't stay broadside! Rake her for all you're worth when she swings to her anchor!"

It wasn't until nearly five o'clock that McCrae and I stole a moment to look up.

What a sight -- all around us the Continental ships were in shreds, fascines shattered by grapeshot, rags dripping where sails had been. The British Carleton lay tattered, many casualties making colored dots on her decks. There wasn't a sail flying. She was unmaneuverable, taking volley after volley from our cannons. The sight was tantalizing. We might not win, but we were not losing!

I choked on cannon smoke and blinked stinging eyes at the schooner, where a young officer in a blue uniform was crawling out onto the bowsprit, right in the midst of heavy fire.

"Looks like a midshipman." Henry Hardie squinted his watering eyes. "Other officers must be dead. Poor boy's probably found himself in command."

"He's doing something!" I cried, pointing.

"Getting their jib up," Joe Rochon described. "Gotta give'm credit, if he lives."

Gradually the triangular sail farthest out crawled upward and took some wind. The enemy schooner wobbled, then moved with some purpose, using the wind to turn her bow away from us. The boy on the bowsprit cast a line to one of the English gunboats, which mightily began to tow the schooner out of direct fire. Retreating!

So they had saved their ship, but we had forced them to fall back. We had forced them!

I grew up seven years in seven hours. I had thought battles went an hour or two. But here, from noon until sunset the two forces pounded each other. To our credit, we never folded. Not until dusk did the Inflexible finally crawl upwind enough to get in range. She loosed the malevolence of five broadsides at us, a barbaric way to behave, when one thought about it. The result was much destruction in our line and the further ravaging of the unfortunate Philadelphia. It seemed they were aiming for Washington or Congress, but kept striking the gunboat. Rochon said he thought the British assumed Benedict Arnold must be on one of the galleys, and they were right. Arnold's ruthless drive kept us all firing away. We knew he would never quit, so we never considered quitting, and we hammered Inflexible back to seven hundred yards. When darkness came, even the mighty three-master had to cease fire, unable to aim. After a few last impudent pops, silence spread quickly. When night enclosed us, the struggle waned in a pathetic kind of draw.

For fifteen ships against fifty-three, that was a kind of victory, wasn't it?

Soon we stood on the half-shattered deck, Daniel, Hardie, McCrae, and I, gazing south. A great mesh of darkness shrouded the bay, which now was flat as a pool of ink. Many wounded rested below, some slipping away. We could not help them more.

On the land, Indian fires glowed through the trees, and on the shore of Valcour Island, the British had set our Royal Savage ablaze. The ship burned furiously. Earth, air, fire, and water.

"So different," I murmured, standing beside Daniel. "Even the water. It seems to accept the dead with almost human arms. Your mother said this was the time of year when the gate stands open and the Veil between worlds is thinnest. I think she's right."

Daniel sighed. "This is the autumn equinox. Oh, yes...I can see her standing in a circle of salt like an idiot, hair unbound, cheeks reddened with roan, brows darkened with acorn mash...."

"Here." Exhausted, I drew a folded and sealed paper from my breast pocket. "She told me to give it to you at a key moment. I believe this moment qualifies."

Hardie looked over my shoulder. "More bird skin?"

Daniel opened the envelope, then parted his lips to answer. For a moment he seemed to see his mother's face in the petals. A sorrowful grin tugged at him. "Moonwort...her lasting love."

No matter how he might rave against his mother, a sentiment arose which he could not banish. I had timed this right.

"Accept her, Daniel," I said, "for my sake."

He looked up. "What've you to do with it?"

"Only that I've been...thinking, lately, of leaving the clergy."

This seemed to distress him more than the enemy presence. His eyes creased with concern. "Adam, why?"

My throat tightened. "Your mother's convictions made me question my own. They seem to be stronger than mine. I am supposed to believe in the miraculous, yet I have never seen it. Seven men died in my arms today, and I still found only confoundment. A minister should never have questions."

"We all have questions," he said gently. "Put aside your doubts. Tonight is no time to give up anything which comforts us."

Seizing the opportunity, I said, "Glad you agree. Put this on."

I raised my fist, from which dangled the leather thong with the crane bag on its end, which I had cherished throughout the day.

Nearby, Rochon, Thorsby, and LaMay plugged a hole in our hull, but kept an eye on us. McCrae took a moment to bind Lavengood's bleeding thigh with an oily rag, but he was listening too.

"Since you were born," I continued, "your mother has shouldered the premonition that her beloved son would die -- "

"In water, yes," Daniel snapped. "All my life she pushed me away from every well and horse trough, wouldn't let me swim, bathed me with a cloth and bucket -- she even did her laundry in a bread kneader!"

I raised a finger in his face. "The Commandment charges, 'Honor thy mother,' not 'Honor thy mother if you approve of her ways.' Instead you ridiculed and tormented her. You swam in the pond. Went riding in rain. Rode in a canoe. Joined the merchant mariners. You became a privateer, all to mock something that embarrassed you. This is your first battle at sea, and she thinks this is it. She begged me to come here."

With a wave of his hand he dismissed what he heard. "I come from a long line of silly fools, many who died at the stake from just this kind of trouble, more who suffered rejection later. My mother is one of these. The whole New Haven community avoids Mary Dickenson. As a boy I watched her suffer loneliness because of her twigs and stones. I was in torment to see her friendless. Only when I married Eloise did she have a companion, a little acceptance. If I die tomorrow, I will die with many men whose mothers saw nothing written in their bobbinlace."

"If you die," I attempted, "do you want me to go back and tell Mary you refused to do this last harmless thing for her? Is that the memory you want her to hold the rest of her life?"

Upon that challenge, I lay the crane bag on the rail beside the smoldering swivelgun, and draped the thong over it. I would not pick it up again. Either he would, or no one would.

He gazed at the bag. "Shall I shun a black cat and avoid the companionway ladder? I've flouted her superstition all my life. You want me to accept it today?"

"I want you to accept that there are forces older and larger than ourselves at work in you. I want you to accept God and accept yourself. Whether you are the end of a line of spiritual channelers I cannot say, but I have seen traits of heightened perception in you. You see things others miss."

"Noticing details is not supernatural. I simply pay attention."

"It's part of what makes you a good captain," Hardie commented. Was he agreeing with me? Or was he simply amused?

"All you have to do is survive the premonition," I finished. "Find a way not to die in the water. Once you're through it, the premonition itself will die. That's what I think."

Daniel pointed at the bag, giving me a quizzical sidelong glance. "If I put this on, the British will not be able to see me or shoot me?"

It did sound silly. I smiled. "Your mother thought so."

"What will the men think," McCrae charged, "when they see their captain wearing a talisman? This talk is blasphemous! They'll be afraid, lose their confidence -- "

"Why, doctor?" I challenged. "Do they lose confidence when they see a holly wreath or mistletoe at Christmas? I am a man of God. I've looked into this, and it is not what the witch-hunters say. The old religion is what God let us have for comfort until He could reveal his Word to us. If only Daniel will accept God's tapestry, he can have peace with himself."

The deck fell quiet. Each man became a separate force, alone with his own doubts, demons, and fears.

Perceiving the distress around him, Daniel murmured, "Not the best time for a sermon, Adam." But the acrimony had gone out of him. He seemed suddenly exhausted.

"Put it on, Daniel," I said, "just to keep peace aboard."

Hardie straightened up. "Yes, Daniel, put it on."

"Throw it overboard," Stephen McCrae countered.

The little bag of stuffed bird skin lay beside the swivelgun. Leaning forward toward Daniel, I spoke with subdued honesty. "You need not destroy your mother in order to prevail yourself."

He stared at me, his eyes unrevealing, for long seconds. Something about this last statement made an impression.

"Henry," he announced, "if I vanish, you'll have to take command."

Hardie threw his head back and laughed, the first sound of merriment we had heard. Taking this for a trigger, Daniel snatched up the crane bag and draped the thong over his head. The bag dropped into place on his filthy waistcoat, right over his heart.

He spread his hands. "There. I'm invisible!"

The men laughed. He did seem funny, standing there caked with gunpowder, the little bag hanging around his neck. "Henry, since I've disappeared, will you please send the men back to the repairs? We'll be fighting again come morning light. Let's not sink before then. Start hammering."

"Very well. Let's go, men. Work, work."

His eyes crinkling, Daniel turned to me. "Are you happy now? This'll keep me from dying in the water because I'll catch it on a block and hang myself."

"Boat on the lee side!" someone called.

As we turned, a hard clunk on the larboard side broke our communion. A moment later a powder-burned man with a nightcap of dark hair and a beard swung aboard and came to Daniel. "Arthur Cohn reporting from General Arnold, Captain. Philadelphia has just slipped under. She's gone. Congress has twelve holes in her. She and Washington both have water coming on. On New York, every officer but the captain is dead. Our ammunition's almost exhausted. Even if we wanted to keep fighting come morning, there's trifle to shoot with. The general's going from ship to ship, surveying damage. He says he'll entertain all suggestions from his captains but surrender."

Daniel's face turned grim. Hopelessness set in deep.

"My compliments to the general," he murmured. "I regret to have no suggestions."

Cohn simply nodded and stumbled back to his rowboat, to go to the next in our line and spread this blighted news.

Sympathy for Daniel pierced us all. How daunting must it be for a captain to have no answers when his men are looking to him?

Sullen, he moved away from us to the bow of the sloop, climbed onto a gun truck, leaned forward over the flop of staysail, and simply gazed north, as if to implore the dying wind for one more favor. There he stood alone, and everyone stayed away from him. The sloop creaked around him, her draped headsails licking at his legs like pet dogs trying to ease his anguish.

"We'd better pick up the Savage's survivors," Hardie muttered. "Can't let them be slaughtered by real savages."

"Send them to the New York," I suggested. "She needs a crew."

They all looked at me. Had I said something wrong?

"Fine idea, Parson!" Hardie lauded. "Mighty fine. Go tell your brother. Get his permission."

Beyond much more than a nod for their approval, I wearily trudged to the bow.

"Sorry to interrupt," I began, framing my words carefully, "but we've had an idea about Royal Savage."

Daniel didn't respond, but continued looking northward, into the darkness, his hands clutching the sail canvas. His gaze etched the night.

"Daniel?"

In the faint dust of moonlight from beyond the clouds, his face was chalky, as if someone had sculpted him upon the sky.

I moved closer. "Daniel? Are you all right?"

He continued to stare north. "Shh...can't you smell it?"

"Smell what?"

"The miracle you wanted!" He jumped down from the gun truck and gave me a cheery shake, then called, "Henry! Signal the general's rowboat. Get him over here!"

"General, my compliments. We have a chance to get away."

"Surrender?" Benedict Arnold looked up at Daniel from his rowboat. "I spit on you for that, sir. Are you afraid to die?"

"No, sir, no, not surrender. Imagine this!" As the crew gathered around us, Daniel's enthusiasm brightening his eyes. "Dawn touches the spine of Valcour...the lake turns from black to gray. The British gunners light their linstocks, officers tighten formation...the fog parts...but the bay is empty. Like wraiths, our ships have dissolved with the mist. The night is gone. Precious hours lost. They scout the sound, but we've disappeared. The Royal Navy is deprived of its decisive victory. Imagine their rage, their confusion!"

"Make your point quickly, Sir, I have ships to repair."

"Our duty is to show England that this is a war. We did that today. Tonight, our duty is to show them that the Colonies survived. You pointed out to me that they always choose strength over time. General, let me ask this -- what would you do to have an extra month at this time of year?"

Arnold's sharkish eyes flared beneath the tricorn. "A month in October is critical in these northern lands. Ticonderoga is garrisoned with ten thousand patriots and will take an extended siege for the British to break. If they lay siege, they'll have a bitter winter-long experience for which they're ill-prepared. If they elect not to storm Ticonderoga, they'll have to give us Lake Champlain until next summer."

"A year to prepare our Continental defenses. General, I can give you that year this very night."

Arnold paused. The rowboat rocked, bumping the sloop's shattered gunwales. "How?" he asked.

Daniel leaned over. "Royal Savage may yet prove a patriot. A burning ship is a seductive sight. And listen -- do you hear the British hammers and saws? They're busy making repairs. We're trapped, and they're overconfident. This gives us time to prepare the sweeps and tholepins, shroud our lanterns, confer with our captains, and make the men understand. With a light in the stern of each ship, we can hug the shoreline and follow each other out, right under their noses."

General Arnold paused, his blue eyes fixed unforgivingly upon Daniel. Slowly a picture transferred from Daniel's mind to his. "What will prevent their seeing us move? It's a clear night."

Daniel's conviction was undeniable. "A fog is rising."

"Fog? There's not a wisp!"

"Believe me, it's coming. It will hide us. We need not destroy them to win, General, we simply need deprive them of destroying us and we will have won." Daniel looked at me now, a change that startled me. He placed a meaningful hand upon my arm. "The new needs not destroy the old in order to prevail."

But Benedict Arnold no longer attended the communication between Daniel and me. He was off in his own mind, a plan spinning to life behind his eyes. "Hooded lanterns...a man to guard each light from the British eyes...grease every running block and sheave, bind the anchors and chains, grease the locks -- or better, we tear our shirts and muffle the sweeps with cloth."

"Cloth is better, yes."

"Yes!" Abruptly General Arnold smacked the side of Enterprise with the flat of his hand. "Colonel Wigglesworth can lead the way in Trumbull. I'll call a council of war aboard Congress upon the half hour. Spread the word -- quietly!"

When long fingers of mist came bleeding between the anchored Continental gunships from the north strait, we were ready. The fog rose so thick and white that we could scarce see our own bowsprit. Embracing the new plan, the patriot fleet quietly retrieved our anchors, put out long oar sweeps muffled with cloth, and lit lanterns on our transoms, shrouded so they could be seen only from dead astern. Thus began the ghostly row.

With Trumbull leading the way, we skimmed down the New York shoreline. Speaking not a word, huddled deep in our hulls, the spirit squadron smoked out onto Lake Champlain under the very noses of the Royal Navy. The British, preoccupied with repairs and watching the Royal Savage burn through the fog, never saw us.

For hours we rowed like that, in silence. Finally the order came to put up our tattered sails and try to make our way south. We were well away from Valcour Island, and the British were guarding an evacuated bay.

Daniel found me huddled in the stern of Enterprise, catching what little warmth I could from the lantern whose shroud I was tending. Astern of us, the gunboat Spitfire was only a smudge in the darkness.

"We did it," he said as he knelt beside me. "They'll be raving mad in the morning. They'll waste time searching for us. They can't come south until they're sure we're not at their backs. Meantime, we'll put in at Schuyler Island and make repairs."

"Brilliant, Daniel. You see? You try to resist the spirits running in your blood, but you can't help but perceive things. You knew the Veil was coming. When it arrived, we were ready."

He surveyed me in a mystical way. "The new and old ways find transition in you, Adam, not in me. You're the one who had enough courage to embrace both ways. You are the Veil between old and new."

Draping an arm around my shoulders, Daniel leaned against the Enterprise's shot-pocked taffrail and gave the ship an affectionate pat. Then he plucked a sprig from the remnant of pine branch that had fallen on the deck from the wrecked canopy, and ran it across his lip to take whatever aroma still lingered.

"Do you think," he asked, "mother would like me to bring her a branch of Valcour hemlock?"

Beneath his warmhearted embrace, I smiled. "And we can be home for Halloween."

The young officer who climbed out onto Carleton's bowsprit under fire was nineteen-year-old Midshipman Edward Pellew, later to become Vice Admiral Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, distinguished naval commander during the Napoleonic Wars.

At dawn on October 12, the Royal Navy discovered Valcour Bay mysteriously evacuated. After a fruitless delay hunting for the rebel fleet, they chased the Americans down Lake Champlain. Israel Daniel Dickenson, Dr. Stephen McCrae, and the Enterprise sailed south with Benedict Arnold's tiny fleet and were forced to engage the British a second time with great loss, destruction, and capture. Still Arnold refused to fold. The Americans scuttled several vessels, burned them, and defiantly left their flags flying to show that this was no surrender. They escaped overland, carrying their wounded, and joined the Enterprise sloop, Schooner Revenge, Galley Trumbull, and the Gunboat New York at Fort Ticonderoga, the only surviving ships of their squadron.

The Battle at Valcour Island displayed to the British that the Americans would fight. They now had a taste of what they would face during a siege of Fort Ticonderoga. Thinking twice, they went back to Canada. The long winter months gave the Americans nearly a year to reinforce.

Though Benedict Arnold had displayed unprecedented leadership, the Continental Congress denied him a promotion, partially because several men from Connecticut had already been promoted.

Had the British punched down Lake Champlain without obstacle, the Crown forces would have sliced the Colonies and easily broken them. We owe a second look to the unyielding Arnold, who gave our nation its one and only chance, as well as our thanks to the heroic Captain Dickenson, who set a fine precedence for all Enterprise captains to come.

Let me die in my old American uniform,

the uniform in which I fought my battles.

God forgive me for ever putting on any other.

Benedict Arnold, in England

shortly before his death, 1801

Copyright © 2000 by Paramount Pictures, All Rights Reserved

The Sloop-of-War Enterprise

"In every revolution, there's one man with a vision...."

Captain James T. Kirk, Star Trek

Diane Carey

Diane knows a little more than most of her colleagues about ships and the rigors of command. In addition to being an accomplished author of science fiction and historical fiction, she is also a seafaring type, preferring older vessels. In fact, Diane braved the lash of early winter, crewing aboard the 1893 Schooner Lettie G. Howard and arriving at New York City's docks. She stopped rigging and cooking just long enough to complete the following story.

This summer, Diane adds her own vision to the Star Trek universe with a new series of novels, starting with Wagon Train to the Stars and introducing one and all to the U.S.S. Challenger.

Diane's contributions to Star Trek extend back more than a decade, including the giant novel Final Frontier, which gave readers a glimpse at George Kirk, father to James. She has written six Original Series novels, four novels set during The Next Generation (including the first original story), six adaptations and one original Deep Space Nine story, and two Voyager novelizations.

With her husband, Greg Brodeur, Diane continues to whip up exciting stories, and shrewd readers will detect the loving attention paid to the starships, making them vital characters along with their crew.

Diane adds:

Special thanks to Captain Austin Becker and the Sloop-of-war Providence of Rhode Island, replica of John Paul Jones's fighting ship, for their help and good works in preserving Revolutionary War history.

My admiration and gratitude also go to Captain Erick Tichonuk, First Mate Len Ruth, and all the crew at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum of Basin Harbor, Vermont, for their hospitality and advice, and their faithful tending of the replica Gunboat Philadelphia. The original Philadelphia resides at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Another of Benedict Arnold's gunboats, believed to be the Spitfire, has recently been found at the bottom of Lake Champlain. As a sailor of historic ships, I convey my applause to the team recovering this national treasure, and hope she soon rises to receive the tribute she deserves.

The Veil at Valcour

"Are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties?"

Benedict Arnold, 1775

Dawn, October 11, 1776

"That's the signal gun! Row for it, men! Royal Navy in sight! Heave! Heave!"

Frosted orange leaves roared across the chop. Wind snatched away the coxun's orders. Beneath me a dirty bateau clawed upward, punching through whitecaps against a bitter wind. An hour ago the wind had been at my back. Now, scratching down the Adirondack hemlocks and spruces, it chipped at my nose and cheeks and froze the moisture in my eyes.

"How near are we? Will we see the Continental Navy soon?"

"Heave! Few minutes. Hard over, larboard! Heave!"

rd

Black lake, black land -- the large double-ended bateau muscled up on its right side as if hauled by a winch! I let out a strangled shout and became intimate with the gnawing water at my left elbow. Everything was so black, so dark, that I entertained a brief crazed fear that the men in this boat were the only Americans here and we would face the British ships all alone.

The coxun's fingers dug at my collar as he pulled me back to my seat. "Keep a grip on them fascines there, your honor."

"What happened?"

"Tiller's over. We're coming into the strait."

"It's the devil's own dark! How could you know to turn?"

"Wind dropped. We're in the lee of Valcour Island. We'll meet up with the American navy any minute."

While the boat hurled itself vertical on the unhappy chop, then skated sickeningly downward, I sat upon a prickle of hardwood saplings, twice as long as I was tall, stripped of every branch and tightly bound into nine- or ten-inch bundles so that they were almost tree trunks again. Five of these bundles, a great weight indeed at nearly two hundred pounds each, were strapped across the bateau's wide beam, and caused the boat to wobble and struggle horridly. Along with those, piles of evergreen boughs with warty bark and needles assaulted my legs with every shiver. What could a navy want with trees?

I strained to see into the darkness, but might as well have had a mask over my eyes. The shore of New York, on our left until now, remained invisible. Around us, Lake Champlain was deeply cloaked.

Then, out of the night, came a voice blasting on the wind. "Hands to the tops'l sheets and braces! Bring the tops'l yard abeam! Don't worry, boys, we possess the caution of youth! Other words, none!"

A huge dark mass surged out of the night, angling over my head as if I'd stepped onto a porch. Swinging in a wide arch came a thirty-foot wooden spear with four enormous triangular sails lancing the sky like great teeth. A ship's bowsprit, inches away!

"Oh!" I dropped back and kissed the water again.

Moonless night had hidden an entire ship!

The ship's sides were mounted with bundles of cut evergreens, a shaggy fence making the vessel into a giant bottlebrush. What an otherworldly sight! Camouflage?

"Hard over, Henry!" the voice again came as our bateau rowed abreast of the massive shuddering object. If the boat and the ship came together on the same wave, we'd be crushed. "Port brace, haul away! Lavengood, Thorsby, Barrette, man the bunts and clews. LaMay, show them the lines, quick, man! Barclay and Rochon, lend Hardie a hand! McCrae, your brace is fouled in the spruces. Don't hurt your hands. McCrae, do you hear me? Stephen!"

Black hull planks bumped the bateau. Bracketing his mouth, the coxun shouted up. "On deck! Heave us a painter!"

High above, a wall of angular gray sail snapped in anger. Then, flap, flap...crack! -- the wind filled it! The ship heeled hard, bit the water, and leaped beyond us.

"Sheet her in and stand by! Larboard, slack your sheet! Clew the tops'l! McCrae, what do you think you're doing? Rochon, I said stand by on that sheet!"

That wind-muffled voice -- did I recognize it? Or was it wishfulness after three cargo boats and two fishing smacks?

Just above me, a lantern flickered to life, dancing on the night. Its fiendish glow changed everything. Hemp ropes veined a hundred feet into the sky. Two great wooden strakes carried a huge sail that swung like a swan's wing.

From an unseen hand, a rope snaked out to the bateau, falling a foot from me. The coxun snatched it up, and twisted it to a cleat, and thus we wheeled sidewise toward the surging wooden wall.

"Is this the right ship?" I called. "I'm seeking Israel Daniel Dickenson, aboard the Betsy. Or is it the George? I've got conflicting information on the ship's name."

"We don't call our ships that way." The coxun grasped a spruce bow fixed to the ship and with superhuman power dragged the bateau close, and we skated an inch from disaster. "Get up there, man, before we're beat to splinters!"

As the bateau heaved upward, I stood and put one foot on the bateau's rail. "I'll break my neck!"

"Jump!" the coxun bellowed, "or you'll have seventy ton of sloop in your gullet!"

With one toe I pushed upward, hands scratching for a grip. Boughs rustled, my cloak and tricorn hat disappeared, and I was carried up and away, a fly clinging to a mule's black belly!

"Fend off!" the coxun called. Oars blunted the ship's sides. The boat roached away.

"Heaven help me!" With me riding her wet flank, the ship clawed forward and defied New York's western shore with her long bowsprit. Over me the hostile sail whistled. Above it, a smaller square sail crawled into a bundle and screamed on its yards. I saw all this in an instant -- lines snapped, blocks creaked, water sprayed, boughs whipped, and the yard squawked like an enraged pelican trying to snap me up.

Again, that voice. "Hands to the larboard side, for God's sake!"

A force grabbed me from above. I lost my legs. My body went straight outward on the wind. Headfirst I plunged through the bundled branches and flopped face-first upon a tilted deck. Pressing my hands to the planks, I twisted to look up.

Above me, a narrow man-shaped shadow loomed. "Get those fascines over to Philadelphia and mounted on. Should've been well done by midnight. Give them to Blake, he's the mate. Or Captain Rue himself. Tell them to rig their canopy and hurry! The wind's from the north!"

I rolled over and choked, "Daniel! Thank Heaven!"

The shadow's shoulders lowered some, arms out at his sides. His head tipped forward. Against the bleak sky, shoulder-length unbound hair flew wildly. "Adam Ghent, that's not you on my deck."

He offered no hand to help me up. His unglazed anger was visible even in the dark.

But wait -- the sky had lightened. As I drew to my feet and braced my legs, I could make out men around me doing feverish work, sawing, tying, hauling lines in a clutter of iron tools, round shot, wadding, tackles, blocks, piles of rope, and sponge rammers. A boy of about ten years used a bellows to keep a stone hearth glowing inside a formation of bricks. There were no uniforms. The men wore anything from muslin to buckskin, some with wool vests and tricorns or any manner of hat they could construct, and buff or black breeches. They didn't look like a navy.

I stood upon a deck that took up the front half of the ship. On my left was a snarly-looking black cannon. On my right stood a set of ladder steps leading up to another deck, a higher one, which scooped back to the stern. I could just make out more men up there, minding a huge tiller.

Through the shaggy fence of branches, I saw another ship on the water, almost as large as this one, with two quill-shaped yards jabbing the sky. Massive parallelograms of canvas carried her into a crescent of anchored vessels, a line of ghosts on a moorside vigil. All the boats wore beards made of bundled saplings.

"Who's that?" I pointed at the other sailing vessel.

"The Galley Washington," Daniel answered brusquely, "moving into defensive position. Lavengood, sheet in all you can get. By the saints, if we're not up another point! Good ship!"

To our right was the crescent of anchored vessels, the smaller ones with one mast each, the larger ones, others like the Washington, with two. "What are all these boats?"

Daniel flopped an arm against his thigh. "Why, this, brother, is the Continental Navy! Eight fifty-four foot gunboats, a cutter, two schooners, three galleys, and the sloop you're on. And sad you'll be ever to have laid eyes upon it."

"Why are they anchored? You're not meaning to have a battle this way -- "

"The gunboats are flat-bottomed and square-rigged. They can't hope to maneuver upwind. We'll fight at anchor."

The sloop heeled fiercely and passed the ship called Trumbull, heading northwest, away from the place where we should be anchored.

"We'll be nicking Revenge's sprit at this pace," a man at the tiller commented. He had a black bandana tied onto his russet hair and arms like tree limbs, and he used lines to control the heavy tiller with tackles.

"We'll make anchor with one more tack," Daniel said to him, "and come to our position on the broad reach."

"It'll have to be handy."

"Say it again, Henry, that the Fates hear you over the wind."

In defiance the wind screamed away his words. We cut past four of the gunboats, with their single masts drawing circles on the sky, sails bundled upon slanted yards. At the south of the bay, another sailing ship maneuvered in the cup of the crescent. "Who's that one?" I asked.

"Royal Savage. Quiet, Adam. Ready about! Keep a firm turn on the pins, men. Let's not have a repeat of that ugly little episode yesterday. Let go your jib sheets! Helm over, Henry!"

At the tiller, Henry and two other men suddenly shifted from one side of the ship to the other. Only now, as their cold-reddened toes squeaked on the wet deck, did I realize they were bare of foot. Some had tied cloth about their feet, but these men were wearing rags.

The ship's narrow body shuddered, came to an even keel, rocked briefly on the chop. The long bowsprit bit into the north wind.

"Starboard, haul away your jib sheets!"

The crew's heads disappeared and their elbows pummeled the air. The four triangular sails on the bowsprit whacked like wild horses, making a drumming sound, but the bow came around. The ship turned on a pin, the sails snapped full, and instantly we were faced back east, stabbing the bowsprit at Valcour Island.

"Prepare to haul that gaff down by hand," Daniel ordered. "The sail'll fight you. Hands to the cathead!" When some men looked confused, he added, "Show 'em, Henry. Barrette, man the aft anchor. Men, it's critical both anchors drop at the same time, understood?"

The man called Barrette smiled ruggedly and said, "I can forge 'em, Daniel. Bet I can drop 'em too!"