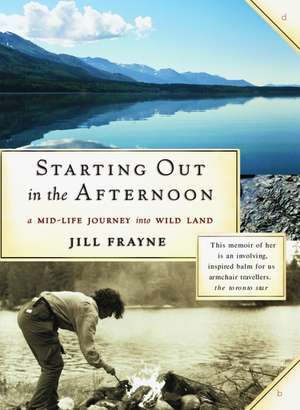

Starting Out in the Afternoon

Autor Frayne, Jill Frayneen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2003

Driving alone across the country from her home just north of Toronto, describing the land as it changes from Precambrian Shield to open prairie, Jill finds that solitude in the wilds is not what she expected. She is actively engaged by nature, her moods reflected in the changing landscape and weather. Camping in her tent as she travels, she begins to let go of the world she’s leaving and to enter the realm of the solitary traveller.

There are many challenges in store. She has booked a place on a two-week sea-kayaking trip in the Queen Charlotte Islands of British Columbia; though she owns a canoe, she has never been in a kayak. As the departure nears, she dreads it. Nor does it work any miracle charm on her, as she is isolated from her fellow travellers; yet the landscape and wild beauty of the old hunt camps gradually affects her. Halfway, as she begins to have energy left at the end of the day’s exertions, she notes: “This is as relaxed as I have ever been, as free from anxious future-thinking as I have ever managed.”

From there she heads north, taking ferries up the Inside Passage and using her bicycle and tent to explore the wet, mountainous places along the way. Again, she feels self-conscious when alone in public, but once she strikes out into nature, the wilderness begins to work its magic on her, and she begins to feel a bond with the land and a kind of serenity. Moreover, she comes to realize that this self-reliance is an important step.

Many travel narratives involve some kind of inner journey, a seeking of knowledge and of self. Set in the same part of the world, Jonathan Raban’s A Passage to Juneau ended up being “an exploration into the wilderness of the human heart.” Kevin Patterson used his months sailing from Vancouver to Tahiti to consider his life in The Water in Between, while the Bhutanese landscape worked a profound transformation on Jamie Zeppa in Beyond the Sky and the Earth. In This Cold Heaven, Gretel Ehrlich chose not to put herself into the story, but described the landscape with a similar hunger and intensity, while Sharon Butala has written deeply and personally about her physical and spiritual connection with the prairies in The Perfection of the Morning and other work.

In Starting Out in the Afternoon, Frayne struggles to come to terms with her vulnerabilities and begins to find peace. In beautifully spare but potent language, she delivers an inspiring, contemplative memoir of the middle passage of a woman’s life and an eloquent meditation on the solace of living close to the wild land. Eventually what has begun as a three-month trip becomes a personal journey of several years, during which she is on the move and testing herself in the wilderness. She conquers her fears and begins a new relationship with nature, exuberant at becoming a competent outdoorswoman. “Despite a late start I expect to spend the rest of my life dashing off the highway, pursuing this know-how, plumbing the outdoors side of life.”

Preț: 97.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 146

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.61€ • 19.36$ • 15.36£

18.61€ • 19.36$ • 15.36£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679311881

ISBN-10: 0679311882

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 163 x 181 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0679311882

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 163 x 181 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

Jill Frayne works as a family therapist in a children’s mental health centre, but, “like lots of women,” has kept a journal all her life. Even in her journal, she edits herself and does the best writing she can. As she approached fifty, she says, “I wanted to impose on myself the discipline of doing the very best writing I could,” not necessarily for publication but for herself. Her three-month journey across the country, and her memory of connection with nature, offered itself as a story. A writer friend read it and said she knew a publisher who would like it.

The publisher advised that it was full of great writing about landscape, but that the reader needed to get to know the person at the centre. Jill asked her daughter Bree and long-term partner Leon for their permission, and wrote herself into the book. During her self-imposed exile in the Yukon, she had been free to examine her life with some sort of detachment, and in rewriting the book she brought that awareness and self-examination into the narrative. She is clear-eyed about human flaws, especially her own.

Jill Frayne grew up in Toronto, one of four children of June Callwood, noted author and social activist, and Trent Frayne, sportswriter and author of many books. When she was growing up, her parents both had offices in the house, clacking away on their typewriters in the midst of family life. There was no expectation on the children to become writers; the parents just “hoped they’d be happy.” Like Jill, her brother and sister have come to writing in their fifties.

Working in Toronto and bringing up a daughter, Jill didn’t properly begin to get at the outdoors until she was well into her thirties, when she edged out of the city, moving to a schoolhouse near Uxbridge, where she “began to roam around the farmers’ fields.” She found the outdoors simultaneously soothing and exhilarating. She says many readers have described her journey as a challenge, but it was actually “the opposite of setting a challenge”: what she was looking for was the comfort she knew the outdoors could give. This journey would be one for which she didn’t need another person.

As the title of the book reflects, Jill was beginning a new phase of life in middle age, and “looking for what to do next internally . . . We have a few starting out times in our lives, not just when we leave home. I was starting out some time after noon.” The biggest challenge in the writing was the process of self-editing, which she describes as being like “combing tangled hair, every draft getting better, until finally the comb starts to run smooth.” Like most writers, she says, she can edit endlessly.

One outcome of the three-month journey into the wilds of Canada was a new home on a bush lot at the northern tip of Algonquin Park, where she has lived now for eleven and a half years. “Life is pretty simple,” she says. “It’s the most soothing place.” Her house has lots of comforts but no plumbing, so she has to fetch water from a nearby well — by car in the summer, and by toboggan in the winter, when the roads aren’t ploughed. She is surrounded by good neighbours: “It’s the practice to stop or at least wave when you drive by . . .slow and chat about the weather, about tasks at hand . . . . Right now the neighbours are taking sap from the trees [for maple syrup].” Driving south to work, she passes small communities where “guys work on the roads or in the bush, and women work in services.” Going into Toronto to visit family and friends is fun. This morning, she describes the gorgeous scene outside: “a sheet of crust,” where yesterday’s warm temperatures and then a sudden drop to 7 below formed ice on the layer of pure snow, which now glints in the sun. Boy, are we lucky!”

She writes on weekends and holidays, when she’s not working; “I love writing.” With the publication of her first book, she is too distracted to think about what she might write next, although there are certainly things she wants to do. “I don’t expect to have this again, but I will certainly keep writing, at least for the drawer.”

The publisher advised that it was full of great writing about landscape, but that the reader needed to get to know the person at the centre. Jill asked her daughter Bree and long-term partner Leon for their permission, and wrote herself into the book. During her self-imposed exile in the Yukon, she had been free to examine her life with some sort of detachment, and in rewriting the book she brought that awareness and self-examination into the narrative. She is clear-eyed about human flaws, especially her own.

Jill Frayne grew up in Toronto, one of four children of June Callwood, noted author and social activist, and Trent Frayne, sportswriter and author of many books. When she was growing up, her parents both had offices in the house, clacking away on their typewriters in the midst of family life. There was no expectation on the children to become writers; the parents just “hoped they’d be happy.” Like Jill, her brother and sister have come to writing in their fifties.

Working in Toronto and bringing up a daughter, Jill didn’t properly begin to get at the outdoors until she was well into her thirties, when she edged out of the city, moving to a schoolhouse near Uxbridge, where she “began to roam around the farmers’ fields.” She found the outdoors simultaneously soothing and exhilarating. She says many readers have described her journey as a challenge, but it was actually “the opposite of setting a challenge”: what she was looking for was the comfort she knew the outdoors could give. This journey would be one for which she didn’t need another person.

As the title of the book reflects, Jill was beginning a new phase of life in middle age, and “looking for what to do next internally . . . We have a few starting out times in our lives, not just when we leave home. I was starting out some time after noon.” The biggest challenge in the writing was the process of self-editing, which she describes as being like “combing tangled hair, every draft getting better, until finally the comb starts to run smooth.” Like most writers, she says, she can edit endlessly.

One outcome of the three-month journey into the wilds of Canada was a new home on a bush lot at the northern tip of Algonquin Park, where she has lived now for eleven and a half years. “Life is pretty simple,” she says. “It’s the most soothing place.” Her house has lots of comforts but no plumbing, so she has to fetch water from a nearby well — by car in the summer, and by toboggan in the winter, when the roads aren’t ploughed. She is surrounded by good neighbours: “It’s the practice to stop or at least wave when you drive by . . .slow and chat about the weather, about tasks at hand . . . . Right now the neighbours are taking sap from the trees [for maple syrup].” Driving south to work, she passes small communities where “guys work on the roads or in the bush, and women work in services.” Going into Toronto to visit family and friends is fun. This morning, she describes the gorgeous scene outside: “a sheet of crust,” where yesterday’s warm temperatures and then a sudden drop to 7 below formed ice on the layer of pure snow, which now glints in the sun. Boy, are we lucky!”

She writes on weekends and holidays, when she’s not working; “I love writing.” With the publication of her first book, she is too distracted to think about what she might write next, although there are certainly things she wants to do. “I don’t expect to have this again, but I will certainly keep writing, at least for the drawer.”

Extras

One

Starting Out

The spring my daughter finished high school, I packed up the car with everything I’d need to live outdoors for three months, everything I could think of for travel by car, kayak, bicycle and ferry, glanced one more time around my yard, which would go unplanted that year, and backed out of the driveway.

My first night I got as far as Georgian Bay, turning in at a provincial park–empty this early in the season–and setting up camp beside a bog with a huge dome of granite in the middle. I was too miserable to eat, the prospect of the journey closing my throat. I sat cross-legged in my tent, a nylon clam open to the white twilight, relieved to be out of the car, with its summers’ worth of paraphernalia: camping gear and groceries, feather pillows and books, backpack and rainwear. We stress ourselves in order to change, and this time I’d chosen solitude and wild land as the forge.

After three days of driving I was still in Ontario. We think of the province as a pan of paved-over ground along the shore of Lake Ontario, a stretch of a hundred kilometres where most of us live, but the real Ontario is the Precambrian Shield–the great wastes of rock overarching tiny southern Ontario in an endless tract of elemental granite and pointed black spruce. The land up here is ponderous, orchestral, especially where the road follows Lake Superior, giving tremendous views of the hills standing up to their mighty shoulders in the sea. Once you leave Superior, though, and plunge into boreal forest–the dark, acid, interminable land west of Thunder Bay–the project of getting out of Ontario becomes daunting. This rock carapace is nothing less than the bulge of the earth’s raw core, scarred, disordered, primordial. The density and weight of the rock have an emotional quality that penetrates the mind. Time seems to clog in the runty trees and gravity tugs in a bold, unbounded way like nowhere else.

When the prairie comes at last, it’s like emerging from a spelunking expedition, rescued by the sky, hauled up and out into the light. On the prairie there is no rock at all, no jagged angles, no glittering lakes, no lowering skies stabbed with evergreens. The morphology of prairie is round.

Past Kenora, the heavy sky and cut rock of the Shield quickly give way to open Manitoba prairie, the road straightening and stretching till it looks like a drawn wire slicing into the horizon. I ducked south of Winnipeg and drove into the setting sun, the evening sky a violet shawl around me.

West of Winnipeg the horizon was dead flat, the only feature the occasional picket of willows barricading a farm. Secondary roads ran along beside the highway with pinprick vehicles, miles off, raising plumes of dust. Farmers, still on their machines in the spring twilight, turned the black ground. Bugs loaded up and baked on the car grille, and any time I slowed, the cool fields filled with birdsong. I turned off the highway and, in the last mauve light of day, found a campground on Lake Winnipeg in a willow grove full of singing birds and shadflies.

* * * * *

Those first days, driving queasily through the Precambrian scenery, unreeling the tender thread between me and home, I had doubts about my expedition, alone in a car on a three-month excursion to the Yukon.

We all have spells of high suggestibility, and I was in one the previous September when I heard a radio interview with a painter, Doris McCarthy. She would have been close to eighty at the time, her voice cheerful and nicotine-cracked, her breathtaking Arctic canvases floating in my memory. At nine-thirty in the morning, while I drove to work from my home near Uxbridge, she and Peter Gzowski were reminiscing about Pangnirtung, a village on Baffin Island they both know. One of them recalled being there in July and, from a window, watching the freed ice move up the bay on the tide and out again on the ebb. Eyeing the approaching Scarborough skyline from my car, a fortress of upended concrete shoe-boxes under a bloom of smog, I was gripped by this image, by the elegance of this event, and I set my mind to go there.

Ideas that lay hold like this have to turn immutable in the mind if they’re going to amount to anything. When I discovered that Pangnirtung is not reachable by car, I could not let myself be deterred. I gave notice at my job and started telling people I was going to drive up to the Arctic the coming summer.

It was not so whimsical a resolve as it may seem. I’d managed a show of equanimity through my daughter’s adolescence and through a long renegotiation of terms with the man I’d been living with. I’d been seven years at a counselling agency fifty miles from home, where I spent my time listening to other harried families. I was watching for a harbinger of change. I believe in the accuracy of ideas that come in this way. After long suspense, long inertia, everything rushes together at once in a notion that has great force. This northern image had such vitality that I would go north even if I couldn’t get to the ice floes.

June 17, 1990

The shrubs around the picnic table where I sit writing this morning are shaking with birds. I see kinds I thought had vanished–those darting ones that never seem to land–and a Baltimore oriole, his breast the colour of marigolds. Walking in the fields the other side of the thicket this morning, I saw a wedge of pelicans pass overhead, shining white birds rowing the sky without making a sound. They flew exactly in sync, their huge wings closing the air in slow unison. Beat . . . beat . . . beat . . . glide.

I pack up finally, whisking shadflies off my tent fly, and retrace the route out to the highway. In spite of the heat it’s barely spring, last year’s fields still white and razed. Only the rims of ditches show a rind of green. The houses, in clouds of muzzy willow, are built tall with narrow, tree-blocked windows, and have a secretive, forestalling look. Pickup trucks tilt in the front yards as though the drivers had to get out fast. I conjure secret strife going on behind the walls in rooms of filtered light. There’s a dogged atmosphere to these places, as if people living here are pitched against an enemy.

As the landscape empties, road signs get more frequent as though to keep up contact with motorists as we drive beyond the pale.

Check Your Odometer.

Start Check Now. 0––1––2––

Put Your Garbage Into Orbit. 5 kms.

Orbit. 10 secs.

I begin to look forward to Saskatchewan, which can’t afford road commentary and garbage cans resembling spaceships.

Starting Out

The spring my daughter finished high school, I packed up the car with everything I’d need to live outdoors for three months, everything I could think of for travel by car, kayak, bicycle and ferry, glanced one more time around my yard, which would go unplanted that year, and backed out of the driveway.

My first night I got as far as Georgian Bay, turning in at a provincial park–empty this early in the season–and setting up camp beside a bog with a huge dome of granite in the middle. I was too miserable to eat, the prospect of the journey closing my throat. I sat cross-legged in my tent, a nylon clam open to the white twilight, relieved to be out of the car, with its summers’ worth of paraphernalia: camping gear and groceries, feather pillows and books, backpack and rainwear. We stress ourselves in order to change, and this time I’d chosen solitude and wild land as the forge.

After three days of driving I was still in Ontario. We think of the province as a pan of paved-over ground along the shore of Lake Ontario, a stretch of a hundred kilometres where most of us live, but the real Ontario is the Precambrian Shield–the great wastes of rock overarching tiny southern Ontario in an endless tract of elemental granite and pointed black spruce. The land up here is ponderous, orchestral, especially where the road follows Lake Superior, giving tremendous views of the hills standing up to their mighty shoulders in the sea. Once you leave Superior, though, and plunge into boreal forest–the dark, acid, interminable land west of Thunder Bay–the project of getting out of Ontario becomes daunting. This rock carapace is nothing less than the bulge of the earth’s raw core, scarred, disordered, primordial. The density and weight of the rock have an emotional quality that penetrates the mind. Time seems to clog in the runty trees and gravity tugs in a bold, unbounded way like nowhere else.

When the prairie comes at last, it’s like emerging from a spelunking expedition, rescued by the sky, hauled up and out into the light. On the prairie there is no rock at all, no jagged angles, no glittering lakes, no lowering skies stabbed with evergreens. The morphology of prairie is round.

Past Kenora, the heavy sky and cut rock of the Shield quickly give way to open Manitoba prairie, the road straightening and stretching till it looks like a drawn wire slicing into the horizon. I ducked south of Winnipeg and drove into the setting sun, the evening sky a violet shawl around me.

West of Winnipeg the horizon was dead flat, the only feature the occasional picket of willows barricading a farm. Secondary roads ran along beside the highway with pinprick vehicles, miles off, raising plumes of dust. Farmers, still on their machines in the spring twilight, turned the black ground. Bugs loaded up and baked on the car grille, and any time I slowed, the cool fields filled with birdsong. I turned off the highway and, in the last mauve light of day, found a campground on Lake Winnipeg in a willow grove full of singing birds and shadflies.

* * * * *

Those first days, driving queasily through the Precambrian scenery, unreeling the tender thread between me and home, I had doubts about my expedition, alone in a car on a three-month excursion to the Yukon.

We all have spells of high suggestibility, and I was in one the previous September when I heard a radio interview with a painter, Doris McCarthy. She would have been close to eighty at the time, her voice cheerful and nicotine-cracked, her breathtaking Arctic canvases floating in my memory. At nine-thirty in the morning, while I drove to work from my home near Uxbridge, she and Peter Gzowski were reminiscing about Pangnirtung, a village on Baffin Island they both know. One of them recalled being there in July and, from a window, watching the freed ice move up the bay on the tide and out again on the ebb. Eyeing the approaching Scarborough skyline from my car, a fortress of upended concrete shoe-boxes under a bloom of smog, I was gripped by this image, by the elegance of this event, and I set my mind to go there.

Ideas that lay hold like this have to turn immutable in the mind if they’re going to amount to anything. When I discovered that Pangnirtung is not reachable by car, I could not let myself be deterred. I gave notice at my job and started telling people I was going to drive up to the Arctic the coming summer.

It was not so whimsical a resolve as it may seem. I’d managed a show of equanimity through my daughter’s adolescence and through a long renegotiation of terms with the man I’d been living with. I’d been seven years at a counselling agency fifty miles from home, where I spent my time listening to other harried families. I was watching for a harbinger of change. I believe in the accuracy of ideas that come in this way. After long suspense, long inertia, everything rushes together at once in a notion that has great force. This northern image had such vitality that I would go north even if I couldn’t get to the ice floes.

June 17, 1990

The shrubs around the picnic table where I sit writing this morning are shaking with birds. I see kinds I thought had vanished–those darting ones that never seem to land–and a Baltimore oriole, his breast the colour of marigolds. Walking in the fields the other side of the thicket this morning, I saw a wedge of pelicans pass overhead, shining white birds rowing the sky without making a sound. They flew exactly in sync, their huge wings closing the air in slow unison. Beat . . . beat . . . beat . . . glide.

I pack up finally, whisking shadflies off my tent fly, and retrace the route out to the highway. In spite of the heat it’s barely spring, last year’s fields still white and razed. Only the rims of ditches show a rind of green. The houses, in clouds of muzzy willow, are built tall with narrow, tree-blocked windows, and have a secretive, forestalling look. Pickup trucks tilt in the front yards as though the drivers had to get out fast. I conjure secret strife going on behind the walls in rooms of filtered light. There’s a dogged atmosphere to these places, as if people living here are pitched against an enemy.

As the landscape empties, road signs get more frequent as though to keep up contact with motorists as we drive beyond the pale.

Check Your Odometer.

Start Check Now. 0––1––2––

Put Your Garbage Into Orbit. 5 kms.

Orbit. 10 secs.

I begin to look forward to Saskatchewan, which can’t afford road commentary and garbage cans resembling spaceships.

Recenzii

“It is a beautifully written book, marked by original language and disciplined prose, every page offering a memorable snapshot of the author’s often impossibly grand physical surroundings…. for anyone who loves the outdoors Starting Out In the Afternoon is a trip worth taking.” -- The Ottawa Citizen

“Starting Out in the Afternoon is a wonderfully written tale of a middle-aged woman’s journey through the wilds of Canada and Alaska. But the book, written in diary form, is more than a travelogue. Woven into the rich descriptions of rugged mountains, mammoth trees and powerful seas are the thoughts of a woman exploring her life’s journey…. The only downside to this work is that it makes the reader grieve for the fact that Frayne didn’t start publishing earlier in life.” -- The Toronto Sun

“Her sentences are spare, yet their images intense. Her eye is sharp.” -- The Edmonton Journal

“Starting Out in the Afternoon is Jilly Frayne’s clear-eyed memoir of the trek -- by car, sneaker and kayak -- that drew her to the Yukon, all the way from her home in southern Ontario and her career as a family therapist. In the end, she discovers that the toughest, most rewarding road trip is the one you take inside your own head and heart.” -- Chatelaine

“With verve, ambition and, it seems, very little fear, [Jill Frayne] conquered B.C.’s northern wilderness, bringing back stories of personal transformation at the mid-point of [her] life.” -- The Vancouver Sun

“Frayne is very much an original, with a bracing, vibrant style fresh as a gust of northern wind. Her memoir of a mid-life trek into deep wilderness is less travelogue than soul-revealing confession, a cri du coeur riddled with the complex, pulsing veins of relationship -- not just with other people, but with that great and glorious enigma, the land…. Frayne writes early on that the initial idea for her journey was inspired by a Peter Gzowski interview on Morningside. How he would have loved this fresh, windy, woodsmoky piece of poetry, so full of passion and vulnerability. No doubt Frayne’s parents are immensely proud of their intrepid, inspired girl.” -- The Gazette (Montreal)

“This memoir of her travels is an involving, inspired balm for us armchair travellers.” -- The Toronto Star

“Frayne’s account of her spiritual and physical journey is a fun, introspective look into the inner workings of a woman’s mind as she reflects on what has been and what is yet possible.” -- The Guelph Mercury

“[A] well-crafted, tough-minded recounting of [Jill Frayne’s] voyage out and then inward . . . . Her metaphors enrich the journey and her personal reflections give the shock of recognition that hard-won truths can bring.” -- Quill and Quire

“[T]he writing is transcendental, ecstatic, as crisp and clear as Lake Superior in October. . . . As the daughter of June Callwood and Trent Frayne, she comes by it honestly, but genetics cannot explain the breath-taking sweep of her style, the depths of her insights. Through words as carefully chosen and necessary as survival gear, she journeys to the heart of her wild self.” -- Wayne Grady, The Globe and Mail

"This voyage of a middle-aged woman through Canada's wildest landscape is so well rendered that the readers longs to take the same journey. As Jill Frayne conquers her own fears, the landscape, which can be rough, cold and unforgiving, comes into focus as a warm, wonderful friend. Frayne writes so beautifully about her relationship with nature that the book becomes a detailed love story." -- Catherine Gildiner, author of Too Close to the Falls

"Jill Frayne's journeys into wilderness are like moving meditations, undertaken with awareness and respect, awash in wisdom, insight and the serenity that exists in the soul of the natural world. Travelling with her is, therefore, a transcendent experience." -- Alison Wearing, author of Honeymoon in Purdah

“Starting Out in the Afternoon is a wonderfully written tale of a middle-aged woman’s journey through the wilds of Canada and Alaska. But the book, written in diary form, is more than a travelogue. Woven into the rich descriptions of rugged mountains, mammoth trees and powerful seas are the thoughts of a woman exploring her life’s journey…. The only downside to this work is that it makes the reader grieve for the fact that Frayne didn’t start publishing earlier in life.” -- The Toronto Sun

“Her sentences are spare, yet their images intense. Her eye is sharp.” -- The Edmonton Journal

“Starting Out in the Afternoon is Jilly Frayne’s clear-eyed memoir of the trek -- by car, sneaker and kayak -- that drew her to the Yukon, all the way from her home in southern Ontario and her career as a family therapist. In the end, she discovers that the toughest, most rewarding road trip is the one you take inside your own head and heart.” -- Chatelaine

“With verve, ambition and, it seems, very little fear, [Jill Frayne] conquered B.C.’s northern wilderness, bringing back stories of personal transformation at the mid-point of [her] life.” -- The Vancouver Sun

“Frayne is very much an original, with a bracing, vibrant style fresh as a gust of northern wind. Her memoir of a mid-life trek into deep wilderness is less travelogue than soul-revealing confession, a cri du coeur riddled with the complex, pulsing veins of relationship -- not just with other people, but with that great and glorious enigma, the land…. Frayne writes early on that the initial idea for her journey was inspired by a Peter Gzowski interview on Morningside. How he would have loved this fresh, windy, woodsmoky piece of poetry, so full of passion and vulnerability. No doubt Frayne’s parents are immensely proud of their intrepid, inspired girl.” -- The Gazette (Montreal)

“This memoir of her travels is an involving, inspired balm for us armchair travellers.” -- The Toronto Star

“Frayne’s account of her spiritual and physical journey is a fun, introspective look into the inner workings of a woman’s mind as she reflects on what has been and what is yet possible.” -- The Guelph Mercury

“[A] well-crafted, tough-minded recounting of [Jill Frayne’s] voyage out and then inward . . . . Her metaphors enrich the journey and her personal reflections give the shock of recognition that hard-won truths can bring.” -- Quill and Quire

“[T]he writing is transcendental, ecstatic, as crisp and clear as Lake Superior in October. . . . As the daughter of June Callwood and Trent Frayne, she comes by it honestly, but genetics cannot explain the breath-taking sweep of her style, the depths of her insights. Through words as carefully chosen and necessary as survival gear, she journeys to the heart of her wild self.” -- Wayne Grady, The Globe and Mail

"This voyage of a middle-aged woman through Canada's wildest landscape is so well rendered that the readers longs to take the same journey. As Jill Frayne conquers her own fears, the landscape, which can be rough, cold and unforgiving, comes into focus as a warm, wonderful friend. Frayne writes so beautifully about her relationship with nature that the book becomes a detailed love story." -- Catherine Gildiner, author of Too Close to the Falls

"Jill Frayne's journeys into wilderness are like moving meditations, undertaken with awareness and respect, awash in wisdom, insight and the serenity that exists in the soul of the natural world. Travelling with her is, therefore, a transcendent experience." -- Alison Wearing, author of Honeymoon in Purdah