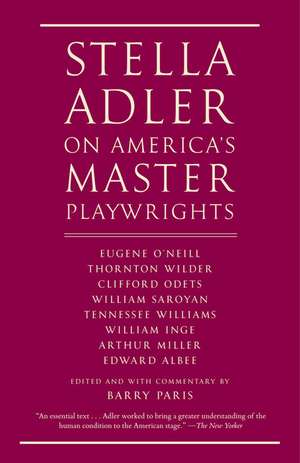

Stella Adler on America's Master Playwrights: Eugene O'Neill, Thornton Wilder, Clifford Odets, William Saroyan, Tennessee Williams, William Inge, Arth

Autor Stella Adler Editat de Barry Parisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 9 sep 2013

This long-awaited companion to her book on the master European playwrights brings to life America’s most revered playwrights, whom she knew, loved, and worked with. Brilliantly edited by Barry Paris, Adler’s lectures on the giants of twentieth-century theater feature her indispensable insights into such classic plays as “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” “The Skin of Our Teeth,” “A Streetcar Named Desire,” “Come Back, Little Sheba,” “The Glass Menagerie,” and “Death of a Salesman,” while shedding new light on such lesser known gems as Tennessee Williams’s “The Lady of Larkspur Lotion” and Arthur Miller’s “After the Fall.” Illuminating, revelatory, inspiring—this is Stella Adler at her electrifying best.

Preț: 128.40 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.57€ • 26.68$ • 20.64£

24.57€ • 26.68$ • 20.64£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679746997

ISBN-10: 0679746994

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0679746994

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Recenzii

“An essential text . . . Adler worked to bring a greater understanding of the human condition to the American stage.” —The New Yorker

“Intoxicating . . . Paris has done a magnificent job. . . Every sentence is a treasure. . . . For actors and actresses this rich material is essential. For those interested in the American theater, it is a must. For cultured people everywhere, this book belongs in their personal canon. . . . It is about so much more than simply bringing to life the work of major artists; it is really the expression of a way of life, and of looking at art as something larger than life." —Peter Bogdanovich, The New York Times Book Review

“Adler’s voice pops into life on the pages . . . Fascinating . . . often hilarious. . . . Adler knows these plays the way a master violist knows her instrument.” —The Boston Globe

“Adler projects to the back of the house. It is indeed the voice of a giant . . . Provides invaluable insights . . . and erupts into sustained verbal fireworks as you’ve never heard elsewhere.” —The New York Times

“Passionate, opinionated, and consummately dramatic, Stella Adler’s voice and personality come through in every word . . . dense and detailed . . . filled with insight, wit, and fervor . . . a lively and fascinating look into the beliefs and methods of the late teacher, who, twenty years after her death, is still regarded as one of the greatest in the history of American theater.” —STAGE Magazine

“[The book is] about so much more than simply bringing to life the work of major artists; it is really the expression of a way of life, and of looking at art as something larger than life. . . . Stella had a marvelous way of mixing erudition with down-to-earth realities, show business know-how with a few Yiddishisms, all combined with a vivid sense of what she called a theater of ‘heightened reality’. . . . This book brings her voice back quite viscerally. It’s Stella talking, taking you on her particular roller-coaster ride through the playwrights and their characters.” —Peter Bogdanovich, The New York Times Book Review

“We usually go to scholars, dramaturgs, and critics for detailed analyses of the modern American theatre. Well, forget that! Here in this amazing book is Stella Adler in full and insightful bloom, preaching, exhorting, insulting, provoking, and always helping her many acting students. Through character study and scene breakdown within a specific play, she manages to give us a personal tour of the times and lives of the 20th Century’s most illustrious playwrights. She knew them, she knew the world they lived in, and she remembers EVERYTHING! A brilliant book.” —Andre Bishop, Lincoln Center Theater

“Stella was a first-name force of nature . . . There is considerable entertainment in the energy of her assertions . . . And then there is the staggering clarity, the piercing insight and the pure, undeniable genius of her dissection of the plays themselves.” —Washington Independent Book Review

“Paris has performed a great service by presenting Adler’s astute perspectives about these writers, whom she knew and admired. Her views are valuable not only for actors, but for anyone interested in the American theatre and its extraordinary achievements.” —Bay Area Reporter

“Intoxicating . . . Paris has done a magnificent job. . . Every sentence is a treasure. . . . For actors and actresses this rich material is essential. For those interested in the American theater, it is a must. For cultured people everywhere, this book belongs in their personal canon. . . . It is about so much more than simply bringing to life the work of major artists; it is really the expression of a way of life, and of looking at art as something larger than life." —Peter Bogdanovich, The New York Times Book Review

“Adler’s voice pops into life on the pages . . . Fascinating . . . often hilarious. . . . Adler knows these plays the way a master violist knows her instrument.” —The Boston Globe

“Adler projects to the back of the house. It is indeed the voice of a giant . . . Provides invaluable insights . . . and erupts into sustained verbal fireworks as you’ve never heard elsewhere.” —The New York Times

“Passionate, opinionated, and consummately dramatic, Stella Adler’s voice and personality come through in every word . . . dense and detailed . . . filled with insight, wit, and fervor . . . a lively and fascinating look into the beliefs and methods of the late teacher, who, twenty years after her death, is still regarded as one of the greatest in the history of American theater.” —STAGE Magazine

“[The book is] about so much more than simply bringing to life the work of major artists; it is really the expression of a way of life, and of looking at art as something larger than life. . . . Stella had a marvelous way of mixing erudition with down-to-earth realities, show business know-how with a few Yiddishisms, all combined with a vivid sense of what she called a theater of ‘heightened reality’. . . . This book brings her voice back quite viscerally. It’s Stella talking, taking you on her particular roller-coaster ride through the playwrights and their characters.” —Peter Bogdanovich, The New York Times Book Review

“We usually go to scholars, dramaturgs, and critics for detailed analyses of the modern American theatre. Well, forget that! Here in this amazing book is Stella Adler in full and insightful bloom, preaching, exhorting, insulting, provoking, and always helping her many acting students. Through character study and scene breakdown within a specific play, she manages to give us a personal tour of the times and lives of the 20th Century’s most illustrious playwrights. She knew them, she knew the world they lived in, and she remembers EVERYTHING! A brilliant book.” —Andre Bishop, Lincoln Center Theater

“Stella was a first-name force of nature . . . There is considerable entertainment in the energy of her assertions . . . And then there is the staggering clarity, the piercing insight and the pure, undeniable genius of her dissection of the plays themselves.” —Washington Independent Book Review

“Paris has performed a great service by presenting Adler’s astute perspectives about these writers, whom she knew and admired. Her views are valuable not only for actors, but for anyone interested in the American theatre and its extraordinary achievements.” —Bay Area Reporter

Extras

Excerpted from the Hardcover Edition

One

Actor vs. Interpreter

There aren’t two actors in the entire Western world who can really play King Lear. I’ll tell you something, there weren’t two actors in America they could find to play Willy in Death of a Salesman, because of the size of the character. There aren’t many who can play these parts. It’s a big stretch for an actor to live up to the playwright. But you can’t do less.

If you say “I’m an actor,” people think you’re an idiot. You come from an American tradition where the actor is buried by the government—or worse, where he is invited to partake in the government. The term “script interpretation” is a profession; it’s your profession. From now on, instead of saying “I’m an actor,” it would be a better idea for you to say “My profession is to interpret a script.”

Let’s start with this: I don’t care what you think about me—good, bad, indifferent—and I don’t care what I think about you. It’s a fair exchange. You have a lot to learn, starting with an understanding that your concept of the theater is the least responsible of any country in the world. I want to make you responsible for being an actor.

You have to come from a tradition where the actor has a better reputation and rightly deserves it. We don’t, because our theater has changed so that it’s not really much of a theater anymore. We’re a film-and-television leftover. That’s going to be pretty permanent, but it doesn’t have to be fatal. After all, the Greek theater is still around; it’s pretty old. The word theater itself comes from the Greeks—it means “the seeing place.” It’s the place where people come to see a spiritual and social X‑ray of their time. The theater was created to tell people the truth about life and the social situation.

Your job is not to “act.” Your job is to interpret. You can’t go on the stage as you are. There are no criteria now, good or bad. Everything is in transition. That is not unusual in history. The French Revolution was a transition. The Great Depression was a transition. During that collapse of our economy, we changed from being a middle-class audience into a lower-middle-class audience with money. We are in transition again now, and if you understand that, you will start to understand something about American theater, which is also in transition.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American theater was just fooling around. I don’t know what we were doing. Nobody does. But I know there were authors called Tolstoy, Chekhov, Andreyev, and Evreinov in Russia; in Germany there was Goethe; in Czechoslovakia there was Cˇapek; in France, Claudel.

From Goethe on, all these very, very good plays existed in Europe. We didn’t have that. But we played their plays. We saw them and acted in them. I acted in one called Bloody Laughter and didn’t understand one word of it. I acted in a lot of plays that were so grown-up, while I was an un-grown‑up American who didn’t know it was my responsibility to understand what I was doing.

Once the playwright has written the play and the play is here, he’s done his job. It’s closed. It lies there. Then it hangs around for people to see or read or study or act in. It is an extremely difficult literary form, that little play—so few pages. That’s a difficult form and one that’s not understood. He has done his job; then you come along. You say, “What’s my job?” You don’t know your job. You don’t even know the name of your job. All you know is, “There’s a play—I’ll act!”

A play has two aspects/essences: it is divided into the literary side (the playwright’s) and the histrionic side (the actor’s). The histrionic side belongs to the actor and to what he puts into it, how he thinks, what he says and understands through it in his mind, his soul, his background, his culture, his personality, his whole being.

That histrionic side of the actor is what he is and what he adds to the play. The play is dead. It lies there. The other side is the side that people fool around with. That’s what makes a man say “I want to be an actor.” He’s no shmegegge; he wants to play King Lear. He wants to play Hamlet.

I remember a man coming to my father once and saying, “I’ve been working on Hamlet for five years.” His name was Jack Barrymore. He was working on The Living Corpse and he played it well. He worked hard at it and then he worked himself into becoming a drunk, a bum, because the transition happened: the transition from a place called the theater (and Broadway was part of that) into a place called the movies. He was called out to do the movies, and he was not a man who understood the movies, even though he beautifully understood words.

So when the playwright’s job is done, you come along and say, “I’ll take it from here and just say his words.”

But you can’t just take his words, because the words, by themselves, won’t help you. You have to take his soul. You have to take his life, his experience of life, his ethic, what he has said to the world. I’m talking about real playwrights. I’m talking about plays that have in them enough to change the thinking of the world. The thinking of the whole world was changed by Ibsen. Nothing was ever the same after Ibsen, because he was a man who, through his craft, through his talent, was able to say the truth. He was able to say it to a certain kind of audience.

His audience was not the king—not royalty or aristocracy. It was you. You were a new audience, something that was happening, and he was telling you the truth.

Are you mature enough to take on the Greek classics? I don’t know. You would have to study Greek art and architecture and movement. You would have to learn that the temples of religion were connected with the gods, the temple of art had to do with the mind, and the temple of the body had to do with what it was to be a man in Greece. You’d have to understand how the discus thrower and the masks were part of that. To be a Greek actor, you’d have to do a lot. First of all, you’d have to look at the statues and architecture. That’s the least you’d have to do—something to understand Greek philosophy.

You are involved with a movement that’s two thousand years old, the first movement of a theater that had a text and a value that are still handed down to us. A major part of Greek culture is in our culture, although we don’t use it; it’s still there. If you go back and study it, you would have a much more serious attitude toward your background. You don’t have enough of a serious attitude toward your theatrical background. It’s not really your fault—it isn’t offered to you.

Understand your profession: “Interpretation” means that I’m going to find the play and the playwright in me. I’m not going to do Ibsen if it’s Chekhov. I’m not going to do Chekhov if it’s Strindberg. I’m not going to do Strindberg if it’s Shaw. These are different playwrights with different minds, and they say different things. The things they say will stay in literature forever. They want something. They have the mind to say something. They find the form to say it.

An actor has to be big, enormous—a giant. His mind, his feeling, his ability to interpret must be that of a giant.

You have to find the character and the place that he is working in. You have to be able to wear the costume. You have to use the words. You have to have the ideas. You have to have the back of the ideas. You have to experience the ideas. You have to have the soul of the ideas.

Shaw didn’t act. Chekhov didn’t act. Strindberg acted. It led him to the insane asylum. He was there for a long time . . . These men were connected with different kinds of theaters. They were the great Europeans.

We’re going to do Odets, Miller, Wilder, O’Neill, Tennessee Williams. They are the great Americans. The American problem of interpretation is very different from the European. I told you that Mr. Barrymore said, “I worked five years on a play.” He certainly didn’t work on the words, did he? Everybody knows the words: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” It’s not the words. It’s a specific author in a specific moment in history and a specific style that he worked on.

I’ll say it again: every playwright writes in a specific moment in history. He does not write your history. He’s not writing about Reagan. That’s not his president. It may be Wilson or Roosevelt or Jefferson. There’s a difference between Reagan and Jefferson that comes out of the time. You can’t put Jefferson in Reagan’s time or Reagan in Jefferson’s. Every play comes out of the author in a special moment in history, and there’s a special style that goes with that moment. Mr. Jefferson was very close to the French government. He understood and was educated, had a great deal to do with foreign countries. I don’t think Mr. Reagan went abroad unless he was paid for it. Every writer writes in his style. The style comes out of his moment in history.

The Greeks wrote in their moment of history. Shakespeare wrote in his. Chekhov wrote in his moment. Odets wrote in his. If you agree that the moment in history determines a great deal of what the playwright wants to say, then you will not say “I think I’ll play in Shaw” without knowing the moment in history that created Shaw. Shaw influenced the whole British government! He was influential enough to make a big impression on English society through his dynamic work.

When you do an author, you must know him. If you don’t know the author, you’re crazy. You must understand him and his time, not your time. Your time is quite easily understood. You live in a very industrial moment. There are cars. There’s electricity. There’s manufacturing. There is science. It’s your time. It’s not Shakespeare’s time. There’s no electricity in Shakespeare’s time. The time element is the most important thing: the moment in which your playwright is writing; the ethic of that time—the fact that women are sitting here in pants—is very different from the ethic at the moment when Mr. Shaw wrote his plays. There were no [women in] pants. The fact that you wear pants means that a lot has changed. The fact that your hair is cut long or short represents a tremendous change in world circumstances. Walking around in the streets with long hair down to your waist was a sign of insanity not too long ago.

If you went out on the stage in Samson and Delilah, you would be considered insane just because you had long hair. It belonged in the bedroom or in the hospital. It did not belong in the drawing room.

Your profession is to interpret, and you have to interpret your time. Your time is different than any other. It is an industrial and scientific time. If you understand that, you will understand also that with it goes a certain kind of ethic. In a previous time, most people went to church. Then Mr. Darwin came along and said, “Never mind the church. You came from a monkey, so shut up about it—you don’t need a God.” But a lot of people said, “I don’t care if I came from a monkey—I still feel like I came from God.” Then Freud came along and said that people’s confusion came from their psychological inability to solve what was going on in their inner self. He saved a great many people from the insane asylum. Then another kind of a man came along, Mr. Einstein, who changed the world by making the physics of the universe clearer. His scientific mind changed the world.

The world gets changed by certain people. They can be scientists or writers. Listen to them. You don’t listen well enough. I want you to gain an understanding of how to listen. All your life you have thought you listen, but you have heard only about one hundredth of what was said to you because you don’t understand that true listening is something that comes from your soul, your blood, your concentration, your mind.

Listening is a very difficult thing. You must acquire the asset of listening with all of your instinctive abilities.

If you speak about the English actors, you would say that Olivier has a lot of craft, which means he has the essential beginnings with which to interpret. If you have the craft of the piano, you have the beginning of being able to play the piano with talent. There is no profession without craft, except yours.

Do you understand the difference between craft and the result of craft, which is talent? Nobody says “I want to play the piano at Carnegie Hall” before they take some lessons. You can imagine what it would sound like.

As an actor you need craft. Mr. Olivier can hold the curtain up. He knows how the play is built. He’s thought about it. You could say he knows how to act. He knows how to handle the part. If you talk about Ralph Richardson, you’d say he knows how to handle the part and you don’t have to worry about him. Sometimes you have to worry about Mr. Olivier, because his craft is bigger than his talent, greater. But once in a while he will give a great performance.

Craft is the basic thing in the beginning of this work for you to understand: it is your handle. It is not your talent. But you must have it. The pianist has it. The flutist has it. The painter has it. Everybody has it except the modern actor. We don’t have it, and therefore we have very few actors. We have nobody that we can send to Europe. Well, we can send a type to Europe. De Niro would be a very good type to send to Europe.

But everybody is suited for more than what they look like. For instance, you know what I look like. You’ll tell me the truth, and I don’t want to hear it: I look a little like an ex-Hollywood star. I’m rather pretty and graceful. I have a lot of assets, but I’m really a character actress. I played servants, peasants, secretaries, queens. I played every goddamned thing they could think of when they couldn’t give it to anyone else.

One

Actor vs. Interpreter

There aren’t two actors in the entire Western world who can really play King Lear. I’ll tell you something, there weren’t two actors in America they could find to play Willy in Death of a Salesman, because of the size of the character. There aren’t many who can play these parts. It’s a big stretch for an actor to live up to the playwright. But you can’t do less.

If you say “I’m an actor,” people think you’re an idiot. You come from an American tradition where the actor is buried by the government—or worse, where he is invited to partake in the government. The term “script interpretation” is a profession; it’s your profession. From now on, instead of saying “I’m an actor,” it would be a better idea for you to say “My profession is to interpret a script.”

Let’s start with this: I don’t care what you think about me—good, bad, indifferent—and I don’t care what I think about you. It’s a fair exchange. You have a lot to learn, starting with an understanding that your concept of the theater is the least responsible of any country in the world. I want to make you responsible for being an actor.

You have to come from a tradition where the actor has a better reputation and rightly deserves it. We don’t, because our theater has changed so that it’s not really much of a theater anymore. We’re a film-and-television leftover. That’s going to be pretty permanent, but it doesn’t have to be fatal. After all, the Greek theater is still around; it’s pretty old. The word theater itself comes from the Greeks—it means “the seeing place.” It’s the place where people come to see a spiritual and social X‑ray of their time. The theater was created to tell people the truth about life and the social situation.

Your job is not to “act.” Your job is to interpret. You can’t go on the stage as you are. There are no criteria now, good or bad. Everything is in transition. That is not unusual in history. The French Revolution was a transition. The Great Depression was a transition. During that collapse of our economy, we changed from being a middle-class audience into a lower-middle-class audience with money. We are in transition again now, and if you understand that, you will start to understand something about American theater, which is also in transition.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, American theater was just fooling around. I don’t know what we were doing. Nobody does. But I know there were authors called Tolstoy, Chekhov, Andreyev, and Evreinov in Russia; in Germany there was Goethe; in Czechoslovakia there was Cˇapek; in France, Claudel.

From Goethe on, all these very, very good plays existed in Europe. We didn’t have that. But we played their plays. We saw them and acted in them. I acted in one called Bloody Laughter and didn’t understand one word of it. I acted in a lot of plays that were so grown-up, while I was an un-grown‑up American who didn’t know it was my responsibility to understand what I was doing.

Once the playwright has written the play and the play is here, he’s done his job. It’s closed. It lies there. Then it hangs around for people to see or read or study or act in. It is an extremely difficult literary form, that little play—so few pages. That’s a difficult form and one that’s not understood. He has done his job; then you come along. You say, “What’s my job?” You don’t know your job. You don’t even know the name of your job. All you know is, “There’s a play—I’ll act!”

A play has two aspects/essences: it is divided into the literary side (the playwright’s) and the histrionic side (the actor’s). The histrionic side belongs to the actor and to what he puts into it, how he thinks, what he says and understands through it in his mind, his soul, his background, his culture, his personality, his whole being.

That histrionic side of the actor is what he is and what he adds to the play. The play is dead. It lies there. The other side is the side that people fool around with. That’s what makes a man say “I want to be an actor.” He’s no shmegegge; he wants to play King Lear. He wants to play Hamlet.

I remember a man coming to my father once and saying, “I’ve been working on Hamlet for five years.” His name was Jack Barrymore. He was working on The Living Corpse and he played it well. He worked hard at it and then he worked himself into becoming a drunk, a bum, because the transition happened: the transition from a place called the theater (and Broadway was part of that) into a place called the movies. He was called out to do the movies, and he was not a man who understood the movies, even though he beautifully understood words.

So when the playwright’s job is done, you come along and say, “I’ll take it from here and just say his words.”

But you can’t just take his words, because the words, by themselves, won’t help you. You have to take his soul. You have to take his life, his experience of life, his ethic, what he has said to the world. I’m talking about real playwrights. I’m talking about plays that have in them enough to change the thinking of the world. The thinking of the whole world was changed by Ibsen. Nothing was ever the same after Ibsen, because he was a man who, through his craft, through his talent, was able to say the truth. He was able to say it to a certain kind of audience.

His audience was not the king—not royalty or aristocracy. It was you. You were a new audience, something that was happening, and he was telling you the truth.

Are you mature enough to take on the Greek classics? I don’t know. You would have to study Greek art and architecture and movement. You would have to learn that the temples of religion were connected with the gods, the temple of art had to do with the mind, and the temple of the body had to do with what it was to be a man in Greece. You’d have to understand how the discus thrower and the masks were part of that. To be a Greek actor, you’d have to do a lot. First of all, you’d have to look at the statues and architecture. That’s the least you’d have to do—something to understand Greek philosophy.

You are involved with a movement that’s two thousand years old, the first movement of a theater that had a text and a value that are still handed down to us. A major part of Greek culture is in our culture, although we don’t use it; it’s still there. If you go back and study it, you would have a much more serious attitude toward your background. You don’t have enough of a serious attitude toward your theatrical background. It’s not really your fault—it isn’t offered to you.

Understand your profession: “Interpretation” means that I’m going to find the play and the playwright in me. I’m not going to do Ibsen if it’s Chekhov. I’m not going to do Chekhov if it’s Strindberg. I’m not going to do Strindberg if it’s Shaw. These are different playwrights with different minds, and they say different things. The things they say will stay in literature forever. They want something. They have the mind to say something. They find the form to say it.

An actor has to be big, enormous—a giant. His mind, his feeling, his ability to interpret must be that of a giant.

You have to find the character and the place that he is working in. You have to be able to wear the costume. You have to use the words. You have to have the ideas. You have to have the back of the ideas. You have to experience the ideas. You have to have the soul of the ideas.

Shaw didn’t act. Chekhov didn’t act. Strindberg acted. It led him to the insane asylum. He was there for a long time . . . These men were connected with different kinds of theaters. They were the great Europeans.

We’re going to do Odets, Miller, Wilder, O’Neill, Tennessee Williams. They are the great Americans. The American problem of interpretation is very different from the European. I told you that Mr. Barrymore said, “I worked five years on a play.” He certainly didn’t work on the words, did he? Everybody knows the words: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” It’s not the words. It’s a specific author in a specific moment in history and a specific style that he worked on.

I’ll say it again: every playwright writes in a specific moment in history. He does not write your history. He’s not writing about Reagan. That’s not his president. It may be Wilson or Roosevelt or Jefferson. There’s a difference between Reagan and Jefferson that comes out of the time. You can’t put Jefferson in Reagan’s time or Reagan in Jefferson’s. Every play comes out of the author in a special moment in history, and there’s a special style that goes with that moment. Mr. Jefferson was very close to the French government. He understood and was educated, had a great deal to do with foreign countries. I don’t think Mr. Reagan went abroad unless he was paid for it. Every writer writes in his style. The style comes out of his moment in history.

The Greeks wrote in their moment of history. Shakespeare wrote in his. Chekhov wrote in his moment. Odets wrote in his. If you agree that the moment in history determines a great deal of what the playwright wants to say, then you will not say “I think I’ll play in Shaw” without knowing the moment in history that created Shaw. Shaw influenced the whole British government! He was influential enough to make a big impression on English society through his dynamic work.

When you do an author, you must know him. If you don’t know the author, you’re crazy. You must understand him and his time, not your time. Your time is quite easily understood. You live in a very industrial moment. There are cars. There’s electricity. There’s manufacturing. There is science. It’s your time. It’s not Shakespeare’s time. There’s no electricity in Shakespeare’s time. The time element is the most important thing: the moment in which your playwright is writing; the ethic of that time—the fact that women are sitting here in pants—is very different from the ethic at the moment when Mr. Shaw wrote his plays. There were no [women in] pants. The fact that you wear pants means that a lot has changed. The fact that your hair is cut long or short represents a tremendous change in world circumstances. Walking around in the streets with long hair down to your waist was a sign of insanity not too long ago.

If you went out on the stage in Samson and Delilah, you would be considered insane just because you had long hair. It belonged in the bedroom or in the hospital. It did not belong in the drawing room.

Your profession is to interpret, and you have to interpret your time. Your time is different than any other. It is an industrial and scientific time. If you understand that, you will understand also that with it goes a certain kind of ethic. In a previous time, most people went to church. Then Mr. Darwin came along and said, “Never mind the church. You came from a monkey, so shut up about it—you don’t need a God.” But a lot of people said, “I don’t care if I came from a monkey—I still feel like I came from God.” Then Freud came along and said that people’s confusion came from their psychological inability to solve what was going on in their inner self. He saved a great many people from the insane asylum. Then another kind of a man came along, Mr. Einstein, who changed the world by making the physics of the universe clearer. His scientific mind changed the world.

The world gets changed by certain people. They can be scientists or writers. Listen to them. You don’t listen well enough. I want you to gain an understanding of how to listen. All your life you have thought you listen, but you have heard only about one hundredth of what was said to you because you don’t understand that true listening is something that comes from your soul, your blood, your concentration, your mind.

Listening is a very difficult thing. You must acquire the asset of listening with all of your instinctive abilities.

If you speak about the English actors, you would say that Olivier has a lot of craft, which means he has the essential beginnings with which to interpret. If you have the craft of the piano, you have the beginning of being able to play the piano with talent. There is no profession without craft, except yours.

Do you understand the difference between craft and the result of craft, which is talent? Nobody says “I want to play the piano at Carnegie Hall” before they take some lessons. You can imagine what it would sound like.

As an actor you need craft. Mr. Olivier can hold the curtain up. He knows how the play is built. He’s thought about it. You could say he knows how to act. He knows how to handle the part. If you talk about Ralph Richardson, you’d say he knows how to handle the part and you don’t have to worry about him. Sometimes you have to worry about Mr. Olivier, because his craft is bigger than his talent, greater. But once in a while he will give a great performance.

Craft is the basic thing in the beginning of this work for you to understand: it is your handle. It is not your talent. But you must have it. The pianist has it. The flutist has it. The painter has it. Everybody has it except the modern actor. We don’t have it, and therefore we have very few actors. We have nobody that we can send to Europe. Well, we can send a type to Europe. De Niro would be a very good type to send to Europe.

But everybody is suited for more than what they look like. For instance, you know what I look like. You’ll tell me the truth, and I don’t want to hear it: I look a little like an ex-Hollywood star. I’m rather pretty and graceful. I have a lot of assets, but I’m really a character actress. I played servants, peasants, secretaries, queens. I played every goddamned thing they could think of when they couldn’t give it to anyone else.

Notă biografică

STELLA ADLER began her life on the stage at the age of five in a production that starred her father, the legendary actor of the Yiddish Theatre, Jacob Adler. Stella Adler was one of the co-founders of the revolutionary Group Theatre. In 1934, she met and studied with Konstantin Stanislavski and began to give acting classes for other members of the Group, including Sanford Meisner and Elia Kazan. Adler established the Stella Adler Conservatory of Acting in 1949 and taught at Yale University.

BARRY PARIS is the author of biographies of Louise Brooks, Greta Garbo, and Audrey Hepburn, and the editor of Stella Adler on Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekov and Stella Adler on America's Master Playwrights.

BARRY PARIS is the author of biographies of Louise Brooks, Greta Garbo, and Audrey Hepburn, and the editor of Stella Adler on Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekov and Stella Adler on America's Master Playwrights.