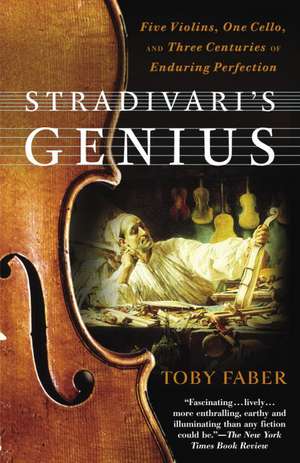

Stradivari's Genius: Five Violins, One Cello, and Three Centuries of Enduring Perfection

Autor Toby Faberen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

Preț: 105.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.21€ • 21.10$ • 16.69£

20.21€ • 21.10$ • 16.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375760853

ISBN-10: 0375760857

Pagini: 265

Ilustrații: 19 B/W ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGOUT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375760857

Pagini: 265

Ilustrații: 19 B/W ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGOUT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Recenzii

“Fascinating . . . lively . . . more enthralling, earthy and illuminating than any fiction could be.”

–The New York Times Book Review

“A celebration of six instruments and the master craftsman who made them . . . [Faber] brings to the subject an infectious fascination with Stradivari’s life and trade. . . . He writes with clarity and fluency.”

–Chicago Tribune

“An extraordinary accomplishment and a compelling read. Like strange totems that cast an irresistible spell, these instruments bring out the best and the worst of those who would own them, and Faber deftly tells the stories in all their rich and surprising detail.”

–Thad Carhart, author of The Piano Shop on the Left Bank

“As Faber traces the history of these standout strings, many engrossing subplots emerge. . . . A worthy contribution to the ongoing legend of Stradivari.”

–Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Fascinating, accessible, and enjoyable.”

–Tracy Chevalier, author of Girl with a Pearl Earring

–The New York Times Book Review

“A celebration of six instruments and the master craftsman who made them . . . [Faber] brings to the subject an infectious fascination with Stradivari’s life and trade. . . . He writes with clarity and fluency.”

–Chicago Tribune

“An extraordinary accomplishment and a compelling read. Like strange totems that cast an irresistible spell, these instruments bring out the best and the worst of those who would own them, and Faber deftly tells the stories in all their rich and surprising detail.”

–Thad Carhart, author of The Piano Shop on the Left Bank

“As Faber traces the history of these standout strings, many engrossing subplots emerge. . . . A worthy contribution to the ongoing legend of Stradivari.”

–Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Fascinating, accessible, and enjoyable.”

–Tracy Chevalier, author of Girl with a Pearl Earring

Notă biografică

Born in Cambridge, England, in 1965, TOBY FABER now lives in London with his wife and daughter. He was previously managing director of his family’s renowned publishing firm, Faber and Faber. This is his first book.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Five violins

and one cello

The Messiah, the Viotti, the Khevenhüller, the Paganini, the Lipi´nski, and the Davidov

THE MESSIAH

Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, founded in 1683, is the oldest institution of its kind in Britain. From Elias Ashmole’s original bequest, it has gone on to establish an enviable reputation for excellence in research and teaching, with an appearance impressive enough to match. Wide stone steps lead up to a grand, if slightly austere, classical façade. The Ashmolean may be smaller than London’s British Museum, or New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, but the overall effect is similar. You feel a proper sense of awe even before stepping over the threshold. Once you do, and if you’re lucky, the guard on duty at the front door will tell you the shortcut: don’t go up the main stairs but turn left, go to the end of the gallery, take the stairs you see on your right, and the Hill Music Room is immediately at the top on the first floor. On your arrival, as likely as not, the room will be shut, with a sign on the door blaming staff shortages and suggesting that, if you particularly wish to see the room’s contents, you should try the invigilator next door.

It is an unpropitious beginning. When you manage to get in, you will find a room only perhaps fifteen by thirty feet. On hot days there will be a fan in the corner to compensate for the lack of air-conditioning. The cork tiles on the floor are scuffed about; protruding nails catch the unwary foot. Curious Old Masters with little obvious connection to music line the walls above the harpsichords and virginals that make up the less interesting part of the Hill Collection. Elsewhere, one case contains bows, while another includes a guitar made by Stradivari himself. It is plain but superbly constructed—testimony to its maker’s range, but far from being the main attraction. In the middle of the room a further case is crowded with eight violins, a viola, and a bass viol. One of the violins was made by Andrea Amati in 1564, part of a commission for Charles IX of France. It is the oldest surviving violin in the world, an exquisite piece of workmanship. The Civic Museum in Cremona has one from the same set, but dated 1566, that was recently valued at $10 million. The Ashmolean’s example has been laid on its back to fit into the case, obscuring what remains of the gilded painting with which the violin was decorated.

Almost every exhibit in this display would be the highlight of another museum’s collection, but here they are no more than also-rans to the star, the only instrument to get its own cabinet, the one that greets you as you walk through the door: the Messiah. There it hangs, suspended in its case, visible from every angle, pristine, its varnish as flawless as when Stradivari applied the last few drops in 1716. It is in mint condition because this, the most famous violin in the world, template for countless copies, has hardly ever been played.

THE VIOTTI

On May 6, 1990, Thomas Bowes gave a recital at the Purcell Room, a small concert hall in London. He was playing a violin he called the Viotti–Marie Hall, after two previous owners. Its looks alone were striking: the immaculate maple back had natural horizontal stripes whose effect Bowes describes as almost psychedelic. But it is the sound that he most remembers now: “That violin was absolutely deafening to play; when you played a sort of high harmonic in G or something on the E string you would actually be slightly in pain; it was so focused; it was like a sort of laser beam. . . . It gave an incredible feeling of power just to know that the smallest touch would just ping out to the back of the biggest hall. . . . There was a kind of awesome perfection about it.”

Bowes’s recital was billed as revisiting the golden age of the violin: the Edwardian era when musicians faced no competition from modern technology for the ears of their prosperous audience. One of the Strad’s eponymous owners, Marie Hall, had been a leading English violinist in the early twentieth century. The recital consisted mainly of music that she would have played, exhibition pieces by some of the great nineteenth-century violinist-composers: Paganini, Spohr, Vieuxtemps, Ernst, and Wieniawski. As for the violin’s connection with Viotti, Europe’s most influential violinist at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the program had this to say: “The Viotti Stradivarius of 1709 was used by Viotti until his death, when it was sold in Paris with other instruments in his possession. Viotti was perhaps one of the first great players to fully appreciate the merits of Stradivarius. The ‘Marie Hall’ ex Viotti Stradivarius is said to have been Viotti’s favorite instrument and is reputed to be the instrument he used when he first visited Paris. It is a magnificent violin, with superb tone; a perfect Stradivarius in every respect.” It is our second violin.

THE KHEVENHÜLLER

Urbane and charming, with a penchant for expensive cigars and a fund of amusing stories, Peter Biddulph is everything one expects a violin expert to be. His dealership has a fine address in London’s West End, and its safe has played host to violins that most players can only covet. He is one of the few dealers in the world who can identify the real thing with confidence and who have the reputation to match their skill. Biddulph’s habit of conducting transactions at either end of a trip on the Concorde earned him, in happier times, the nickname Flying Fiddle. Nowadays he probably regrets the double entendre. A case brought by the heirs of Gerald Segelman, whose violin collection Biddulph helped to disperse after its owner’s death, ended in an out-of-court settlement of £3 million [$4.5 million].* Biddulph had to sell the building that houses his London shop, although he still operates from the basement and a ground-floor reception area. Nevertheless he protests his innocence of anything more serious than bad record-keeping; it was, he says, only his inability to afford a protracted case that led to the settlement.

The Segelman affair has turned an unwelcome spotlight on violin dealers and their role as the final arbiters of authenticity and value. Biddulph could be forgiven for avoiding questions. Nevertheless he is happy to talk, over a mint tea, about the Khevenhüller, the third of our violins, which he sold in 2000 on behalf of one of the oldest violin shops in Japan.

The Khevenhüller Stradivarius was made in 1733, a late masterpiece. One previous owner describes it as “ample and round, varnished a deep glowing red, its grand proportions . . . matched by a sound at once powerful, mellow and sweet.” In the last twenty years it has changed hands many times; this was the second time that Biddulph acted as intermediary. On this occasion it was valued at $4 million. Another dealer had shown it to Maxim Vengerov. He “loved it,” but not enough, apparently, to make him give up the Kreutzer. To my mind, we should admire him for refusing to abandon his “marriage” for a new paramour. Jaime Laredo, the Bolivian American violinist, also tried the Khevenhüller. He too “would have loved it” as a partner to his other great Strad, the Gariel, made in 1717. But he could not raise the funds. Who could afford an asking price like that?

THE PAGANINI

“If the Tokyo String Quartet isn’t the world’s greatest chamber music ensemble, it’s hard to imagine which group is.” Unsurprisingly, the quartet’s publicity likes to repeat that quote from The Washington Post. Less definitive but almost as flattering reviews remark on both the group’s succulent tone and a cohesiveness that persists despite the numerous changes of personnel since the ensemble’s formation in 1969. It would be pleasing to think that both these attributes may partly result from another fact, also repeated in every press release: since 1995 the Tokyo Quartet has played the same set of instruments, all made by Stradivari, the Paganini Quartet.

Named after the nineteenth-century Italian virtuoso who once owned all four instruments, the Paganini Quartet has a legendary status that is almost matched by the quality of its constituent pieces. Stradivari only made two or three great violas, and the Quartet’s, made in 1731, is one of them. The first violin, four years older, was described by Paganini as having a tone as big as a double bass; it too is recognized as a masterpiece. The cello’s label dates it to 1736, the year before its maker’s death, although many place it earlier. It has the reputation of being among the best works of Stradivari’s last years, with perfect proportions that hark back to an earlier era of the Master’s life.

In such exalted company the second violin, made around 1680, is an oddity. Stradivari’s early works are generally thought to be in a lower league than his more mature output, and this violin—the 1680 Paganini—is fifty years older than its counterparts in the Quartet. A string quartet is a partnership of equals. The second violin should never be of poorer quality than the instruments with which it must balance. The answer to why the 1680 Paganini became part of the Quartet lies in its history. It is our fourth violin.

THE LIPI´NSKI

For two hundred years the 1715 Lipi´nski boasted a succession of famous players. One of the biggest violins Stradivari produced, made when he was at his peak, its construction speaks of its maker’s confidence, and the longevity of its fame is surely evidence of his genius. But for more than fifty years it has figured in no performances. Since its last recorded sale in 1962, the Lipi´nski—our final violin—has dropped from sight.

THE DAVIDOV

No such fate is likely to befall the Davidov cello, made in 1712. Yo-Yo Ma, who has played it for the last twenty years, is probably the most celebrated cellist of his generation, and he is eloquent when he describes getting to know his great Stradivarius: “The pianissimos float effortlessly. The instrument’s response is instantaneous. The sound can be rich, sensuous or throbbing at every range, yet can also be clear, cultured and pure. Each sound stimulates the player’s imagination. However, there is no room for error as one cannot push the sound, rather it needs to be released. I had to learn not to be seduced by the sheer beauty of the sound in my mind before trying to coax it from the cello.”

Makers have a similar response to the quality of the Davidov’s workmanship. In a recent article one says: “Antonio Stradivari made this cello to give us all a lesson in humility.” Every aspect of the instrument is remarkable, but it is the varnish that creates the greatest impression: “For a few precious moments toward evening the sun broke into the airy studio and the cello blazed with light. Not only did it change color, it changed in transparency and depth and like some fantastic natural hologram it presented a different image with each new twist and turn.”

The Messiah, the Viotti, the Khevenhüller, the Paganini, the Lipi´nski, and the Davidov: these are our six Strads. Each has its own history. Occasionally two will cross paths, in the collection of a single owner or at the same performance, but there is only one man whose life encompasses all six: Antonio Stradivari himself. And his story begins at least a century before his birth, with the emergence of Cremona at the center of Europe’s nascent violin industry and the royal patron who helped to put it there.

Chapter Two

“The incomparably better violins of cremona”

The Amati dynasty

Under normal circumstances the French royal family would never have considered tainting its line with the blood of a woman whose family, only two or three generations before, had been in trade. But Catherine de Medici was a cousin to Pope Clement VII, with whom the perpetually belligerent François I sought an alliance, and her new husband-to-be, Henri, was only a second son with little prospect of inheriting the throne. So the marriage in October 1533 was quickly arranged, and the wedding night observed by the king, who noted afterward that “each had shown valor in the joust.”

Pope Clement’s death in 1534, less than a year after the nuptials, was therefore a bitter blow. It meant, according to a contemporary Venetian report, that “all of France disapproved of the marriage.” Worse was to come. Henri’s older brother, the dauphin, died in 1536, apparently from drinking ice-cold water immediately after a game of tennis. Catherine, still only seventeen, was destined to be queen of France, responsible above all else for continuing the male line. But for ten years she bore no children, while her husband fathered enough offspring outside his marriage to demonstrate that the problem clearly was not with him. Stuck in a medieval court that followed its monarch around the country, chasing the latest reports of a hart fit to be hunted by a king, Catherine could hardly be blamed for surrounding herself with servants and artists from her native Flor-ence. Even before she acquired any political influence, her cultural connections were starting to be felt.

Over the next twenty years a series of births and deaths transformed Catherine from devoted but neglected wife into the ruler of France. In 1544 she finally gave birth to her first child—what is more, a son. Thoughts of putting her into a nunnery, freeing Henri to take a second, more fertile wife, were finally shelved. Several more sons and daughters were to follow. Her father-in-law’s death in 1547 made Catherine queen, even if her husband elected to spend most of his time with his mistress. Then, in 1559, Henri himself died following a jousting accident. The widowed Catherine was queen mother, a powerful influence over her sickly son François II, who at fourteen was deemed able to rule alone. A year later François’s own death brought his younger brother to the throne. Deft political footwork ensured that Catherine was named as Charles IX’s regent, and she retained her power even when he was judged to have reached his majority in 1563. By then France’s religious wars had already begun. Catherine was unable to stop them, and she must bear some responsibility for the infamous St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Huguenots in 1572. So while she may have planned her lavish festivals and ballets as peaceful diversions, they served only to cast her in the same mold as Nero, fiddling while Rome burned. It is an apt analogy; the court entertainments were accompanied by music from an instrument that had only recently emerged from Italy: the violin.

From the Hardcover edition.

Five violins

and one cello

The Messiah, the Viotti, the Khevenhüller, the Paganini, the Lipi´nski, and the Davidov

THE MESSIAH

Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, founded in 1683, is the oldest institution of its kind in Britain. From Elias Ashmole’s original bequest, it has gone on to establish an enviable reputation for excellence in research and teaching, with an appearance impressive enough to match. Wide stone steps lead up to a grand, if slightly austere, classical façade. The Ashmolean may be smaller than London’s British Museum, or New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, but the overall effect is similar. You feel a proper sense of awe even before stepping over the threshold. Once you do, and if you’re lucky, the guard on duty at the front door will tell you the shortcut: don’t go up the main stairs but turn left, go to the end of the gallery, take the stairs you see on your right, and the Hill Music Room is immediately at the top on the first floor. On your arrival, as likely as not, the room will be shut, with a sign on the door blaming staff shortages and suggesting that, if you particularly wish to see the room’s contents, you should try the invigilator next door.

It is an unpropitious beginning. When you manage to get in, you will find a room only perhaps fifteen by thirty feet. On hot days there will be a fan in the corner to compensate for the lack of air-conditioning. The cork tiles on the floor are scuffed about; protruding nails catch the unwary foot. Curious Old Masters with little obvious connection to music line the walls above the harpsichords and virginals that make up the less interesting part of the Hill Collection. Elsewhere, one case contains bows, while another includes a guitar made by Stradivari himself. It is plain but superbly constructed—testimony to its maker’s range, but far from being the main attraction. In the middle of the room a further case is crowded with eight violins, a viola, and a bass viol. One of the violins was made by Andrea Amati in 1564, part of a commission for Charles IX of France. It is the oldest surviving violin in the world, an exquisite piece of workmanship. The Civic Museum in Cremona has one from the same set, but dated 1566, that was recently valued at $10 million. The Ashmolean’s example has been laid on its back to fit into the case, obscuring what remains of the gilded painting with which the violin was decorated.

Almost every exhibit in this display would be the highlight of another museum’s collection, but here they are no more than also-rans to the star, the only instrument to get its own cabinet, the one that greets you as you walk through the door: the Messiah. There it hangs, suspended in its case, visible from every angle, pristine, its varnish as flawless as when Stradivari applied the last few drops in 1716. It is in mint condition because this, the most famous violin in the world, template for countless copies, has hardly ever been played.

THE VIOTTI

On May 6, 1990, Thomas Bowes gave a recital at the Purcell Room, a small concert hall in London. He was playing a violin he called the Viotti–Marie Hall, after two previous owners. Its looks alone were striking: the immaculate maple back had natural horizontal stripes whose effect Bowes describes as almost psychedelic. But it is the sound that he most remembers now: “That violin was absolutely deafening to play; when you played a sort of high harmonic in G or something on the E string you would actually be slightly in pain; it was so focused; it was like a sort of laser beam. . . . It gave an incredible feeling of power just to know that the smallest touch would just ping out to the back of the biggest hall. . . . There was a kind of awesome perfection about it.”

Bowes’s recital was billed as revisiting the golden age of the violin: the Edwardian era when musicians faced no competition from modern technology for the ears of their prosperous audience. One of the Strad’s eponymous owners, Marie Hall, had been a leading English violinist in the early twentieth century. The recital consisted mainly of music that she would have played, exhibition pieces by some of the great nineteenth-century violinist-composers: Paganini, Spohr, Vieuxtemps, Ernst, and Wieniawski. As for the violin’s connection with Viotti, Europe’s most influential violinist at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the program had this to say: “The Viotti Stradivarius of 1709 was used by Viotti until his death, when it was sold in Paris with other instruments in his possession. Viotti was perhaps one of the first great players to fully appreciate the merits of Stradivarius. The ‘Marie Hall’ ex Viotti Stradivarius is said to have been Viotti’s favorite instrument and is reputed to be the instrument he used when he first visited Paris. It is a magnificent violin, with superb tone; a perfect Stradivarius in every respect.” It is our second violin.

THE KHEVENHÜLLER

Urbane and charming, with a penchant for expensive cigars and a fund of amusing stories, Peter Biddulph is everything one expects a violin expert to be. His dealership has a fine address in London’s West End, and its safe has played host to violins that most players can only covet. He is one of the few dealers in the world who can identify the real thing with confidence and who have the reputation to match their skill. Biddulph’s habit of conducting transactions at either end of a trip on the Concorde earned him, in happier times, the nickname Flying Fiddle. Nowadays he probably regrets the double entendre. A case brought by the heirs of Gerald Segelman, whose violin collection Biddulph helped to disperse after its owner’s death, ended in an out-of-court settlement of £3 million [$4.5 million].* Biddulph had to sell the building that houses his London shop, although he still operates from the basement and a ground-floor reception area. Nevertheless he protests his innocence of anything more serious than bad record-keeping; it was, he says, only his inability to afford a protracted case that led to the settlement.

The Segelman affair has turned an unwelcome spotlight on violin dealers and their role as the final arbiters of authenticity and value. Biddulph could be forgiven for avoiding questions. Nevertheless he is happy to talk, over a mint tea, about the Khevenhüller, the third of our violins, which he sold in 2000 on behalf of one of the oldest violin shops in Japan.

The Khevenhüller Stradivarius was made in 1733, a late masterpiece. One previous owner describes it as “ample and round, varnished a deep glowing red, its grand proportions . . . matched by a sound at once powerful, mellow and sweet.” In the last twenty years it has changed hands many times; this was the second time that Biddulph acted as intermediary. On this occasion it was valued at $4 million. Another dealer had shown it to Maxim Vengerov. He “loved it,” but not enough, apparently, to make him give up the Kreutzer. To my mind, we should admire him for refusing to abandon his “marriage” for a new paramour. Jaime Laredo, the Bolivian American violinist, also tried the Khevenhüller. He too “would have loved it” as a partner to his other great Strad, the Gariel, made in 1717. But he could not raise the funds. Who could afford an asking price like that?

THE PAGANINI

“If the Tokyo String Quartet isn’t the world’s greatest chamber music ensemble, it’s hard to imagine which group is.” Unsurprisingly, the quartet’s publicity likes to repeat that quote from The Washington Post. Less definitive but almost as flattering reviews remark on both the group’s succulent tone and a cohesiveness that persists despite the numerous changes of personnel since the ensemble’s formation in 1969. It would be pleasing to think that both these attributes may partly result from another fact, also repeated in every press release: since 1995 the Tokyo Quartet has played the same set of instruments, all made by Stradivari, the Paganini Quartet.

Named after the nineteenth-century Italian virtuoso who once owned all four instruments, the Paganini Quartet has a legendary status that is almost matched by the quality of its constituent pieces. Stradivari only made two or three great violas, and the Quartet’s, made in 1731, is one of them. The first violin, four years older, was described by Paganini as having a tone as big as a double bass; it too is recognized as a masterpiece. The cello’s label dates it to 1736, the year before its maker’s death, although many place it earlier. It has the reputation of being among the best works of Stradivari’s last years, with perfect proportions that hark back to an earlier era of the Master’s life.

In such exalted company the second violin, made around 1680, is an oddity. Stradivari’s early works are generally thought to be in a lower league than his more mature output, and this violin—the 1680 Paganini—is fifty years older than its counterparts in the Quartet. A string quartet is a partnership of equals. The second violin should never be of poorer quality than the instruments with which it must balance. The answer to why the 1680 Paganini became part of the Quartet lies in its history. It is our fourth violin.

THE LIPI´NSKI

For two hundred years the 1715 Lipi´nski boasted a succession of famous players. One of the biggest violins Stradivari produced, made when he was at his peak, its construction speaks of its maker’s confidence, and the longevity of its fame is surely evidence of his genius. But for more than fifty years it has figured in no performances. Since its last recorded sale in 1962, the Lipi´nski—our final violin—has dropped from sight.

THE DAVIDOV

No such fate is likely to befall the Davidov cello, made in 1712. Yo-Yo Ma, who has played it for the last twenty years, is probably the most celebrated cellist of his generation, and he is eloquent when he describes getting to know his great Stradivarius: “The pianissimos float effortlessly. The instrument’s response is instantaneous. The sound can be rich, sensuous or throbbing at every range, yet can also be clear, cultured and pure. Each sound stimulates the player’s imagination. However, there is no room for error as one cannot push the sound, rather it needs to be released. I had to learn not to be seduced by the sheer beauty of the sound in my mind before trying to coax it from the cello.”

Makers have a similar response to the quality of the Davidov’s workmanship. In a recent article one says: “Antonio Stradivari made this cello to give us all a lesson in humility.” Every aspect of the instrument is remarkable, but it is the varnish that creates the greatest impression: “For a few precious moments toward evening the sun broke into the airy studio and the cello blazed with light. Not only did it change color, it changed in transparency and depth and like some fantastic natural hologram it presented a different image with each new twist and turn.”

The Messiah, the Viotti, the Khevenhüller, the Paganini, the Lipi´nski, and the Davidov: these are our six Strads. Each has its own history. Occasionally two will cross paths, in the collection of a single owner or at the same performance, but there is only one man whose life encompasses all six: Antonio Stradivari himself. And his story begins at least a century before his birth, with the emergence of Cremona at the center of Europe’s nascent violin industry and the royal patron who helped to put it there.

Chapter Two

“The incomparably better violins of cremona”

The Amati dynasty

Under normal circumstances the French royal family would never have considered tainting its line with the blood of a woman whose family, only two or three generations before, had been in trade. But Catherine de Medici was a cousin to Pope Clement VII, with whom the perpetually belligerent François I sought an alliance, and her new husband-to-be, Henri, was only a second son with little prospect of inheriting the throne. So the marriage in October 1533 was quickly arranged, and the wedding night observed by the king, who noted afterward that “each had shown valor in the joust.”

Pope Clement’s death in 1534, less than a year after the nuptials, was therefore a bitter blow. It meant, according to a contemporary Venetian report, that “all of France disapproved of the marriage.” Worse was to come. Henri’s older brother, the dauphin, died in 1536, apparently from drinking ice-cold water immediately after a game of tennis. Catherine, still only seventeen, was destined to be queen of France, responsible above all else for continuing the male line. But for ten years she bore no children, while her husband fathered enough offspring outside his marriage to demonstrate that the problem clearly was not with him. Stuck in a medieval court that followed its monarch around the country, chasing the latest reports of a hart fit to be hunted by a king, Catherine could hardly be blamed for surrounding herself with servants and artists from her native Flor-ence. Even before she acquired any political influence, her cultural connections were starting to be felt.

Over the next twenty years a series of births and deaths transformed Catherine from devoted but neglected wife into the ruler of France. In 1544 she finally gave birth to her first child—what is more, a son. Thoughts of putting her into a nunnery, freeing Henri to take a second, more fertile wife, were finally shelved. Several more sons and daughters were to follow. Her father-in-law’s death in 1547 made Catherine queen, even if her husband elected to spend most of his time with his mistress. Then, in 1559, Henri himself died following a jousting accident. The widowed Catherine was queen mother, a powerful influence over her sickly son François II, who at fourteen was deemed able to rule alone. A year later François’s own death brought his younger brother to the throne. Deft political footwork ensured that Catherine was named as Charles IX’s regent, and she retained her power even when he was judged to have reached his majority in 1563. By then France’s religious wars had already begun. Catherine was unable to stop them, and she must bear some responsibility for the infamous St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Huguenots in 1572. So while she may have planned her lavish festivals and ballets as peaceful diversions, they served only to cast her in the same mold as Nero, fiddling while Rome burned. It is an apt analogy; the court entertainments were accompanied by music from an instrument that had only recently emerged from Italy: the violin.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Almost everyone knows what a Stradivarius is, yet now is told the amazing story of Antonio Stradivari, the 17th-century Italian whose incomparable craftsmanship single-handedly revolutionized the violin and therefore the entire history of Western music.