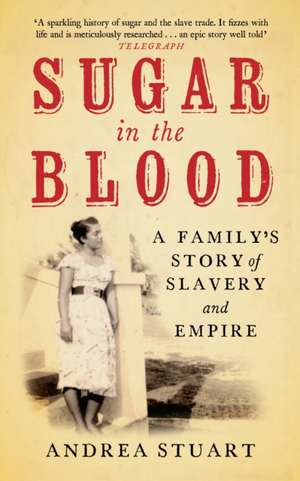

Sugar in the Blood

Autor Andrea Stuarten Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 iun 2013

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 64.61 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.04 lei 6-10 zile |

| GRANTA BOOKS – 6 iun 2013 | 64.61 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.04 lei 6-10 zile |

| VINTAGE BOOKS – 7 oct 2013 | 115.48 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 64.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 97

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.37€ • 12.72$ • 10.26£

12.37€ • 12.72$ • 10.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 29 ianuarie-12 februarie

Livrare express 14-18 ianuarie pentru 23.03 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781846270727

ISBN-10: 1846270723

Pagini: 448

Ilustrații: Illustrations (black and white), maps (black and white)

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: GRANTA BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1846270723

Pagini: 448

Ilustrații: Illustrations (black and white), maps (black and white)

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: GRANTA BOOKS

Notă biografică

Andrea Stuart was born and raised in the Caribbean. She studied English at the University of East Anglia and French at the Sorbonne. Her book The Rose of Martinique: A Life of Napoleon’s Josephine was published in the United States in 2004, has been translated into three languages and won the Enid McLeod Literary Prize. Stuart’s work has been published in numerous anthologies, newspapers and magazines, and she regularly reviews books for The Independent. She has also worked as a TV producer.

Extras

1

There was a wind over England, and it blew.

(Have you heard the news of Virginia?)

A west wind blowing, the wind of a western star,

To gather men’s lives like pollen and cast them forth,

Blowing in hedge and highway and seaport town,

Whirling dead leaf and living but always blowing,

A salt wind, a sea wind, a wind from the world’s end,

From the coasts that have new wild names, from the huge unknown.

—stephen vincent benét, “western star”

george ashby’s story began as all migrants’ stories do: with a journey.

Some time in the late 1630s, when George Ashby was finally given notification that his ship was ready to sail, he must have been afraid. He was a blacksmith, a young man in his late teens, about to leave behind everything he had ever known. Though the voyage carried the seeds of his dreams he, like most of the population, had probably never undergone a long sea journey before and had no real idea of what to expect when he arrived in the Americas.

Those who chose to undertake the fearsome Atlantic crossing in search of a new life were generally tough—or else dangerously foolish. But what else can we know about George Ashby, my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather? Was he fleeing from a family or seeking a new one? Did he dream of religious freedom or of wealth? Was he ambivalent about leaving his homeland or were his life experiences so bitter that he believed nothing in the Americas could be worse? As he set sail for the adventuresome world of the Caribbean he would have had no idea how heavily the odds were stacked against him. (According to one historian, men like him were “pursuing a will-o’-the-wisp,” since very few of them ever achieved the better life they longed for.) He could not know that he would be one of the lucky ones: that he would not just survive but found a dynasty that endures to this day, built on sugar and forged by slavery.

The first sight of the ship would have done nothing to allay his trepidation. The typical merchant vessel that plied the route between the Caribbean and Britain was rated at around 200 tons (meaning that it could accommodate 200 casks or tuns of wine). Trussed against the stone walls of the dock, the ship looked like a gigantic gutted carcass afloat upon the water. The gaunt ribs of the wooden hull curved menacingly into the sky and the base was coated with a shaggy pelt of seaweed and barnacles. It would have been hard for George to countenance that he would be confined in the belly of this behemoth for almost two months, with the real possibility that his journey would end, like that of so many before him, in massacre by pirates or drowning at sea.

After unpacking and settling in, the passengers were summoned on deck to present their documents to the “searchers.” These officials administered the oath of allegiance to the king, stamped each traveller’s ticket with the crucial “Licences under their hands and seals to pass the seas,” and then cleared the vessel for departure. Since every passenger had to undergo this process, no matter what their individual circumstances or where they came from, it represented their first rite of passage, one that made their new status as migrants starkly real.

Still gathered on the bridge, the passengers chatted among themselves or waved to family and friends gathered portside to wish them bon voyage. Then, all of a sudden, a flurry of activity: the sailors scrambling across the deck, busying themselves with a series of tasks that were inexplicable to most of the passengers, the screeching of the anchor as it was winched aboard, the screaming of the hoisted sails, the shouting of the master and the sailors, all combined in a violent auditory assault. As the crew worked furiously in the bows, stern and dock, the passengers jostled to be as near the rails as possible.

Despite the noise and bustle of the ship, most of the migrants would have been as hushed as worshippers in a church, fearful of what the voyage might hold or trying to imagine what lay at the other end. They were aware that the journey was, in all probability, final. Some may have dreamt of returning to their homeland enriched, perhaps even ennobled, but most rightly sensed that they would not be coming back.

To truly grasp what this sea journey meant, what bravery and audacity it required, one must understand how the world was seen and known at that time. Though George Ashby and his contemporaries had been born in the Age of Discovery (1500ߝ1700), most of the world was still terra incognita for Europeans. Maps were often sketchy and inaccurate. Two continents, Australia and Antarctica, had not been traced at all, and vast areas were still blank. The interiors of South America, Africa and Asia had scarcely been explored. Beyond the eastern fringe of North America, which George’s fellow pioneers had begun to document, were millions of square miles of uncharted wilderness.

Like many other countries in the Old World, England was poised between the medieval and the modern, where most people’s lives played out within a narrow radius around their birthplace, and their beliefs were characterized by superstition and ignorance. It was an age in which magic still played a large part in the lives of ordinary people and many firmly believed in witches and fairies, that butterflies were the souls of the dearly departed, and that churchyards swarmed with souls and spirits. In the absence of real information about far-off lands, fantasies abounded: that the east was populated with dog-headed men and basilisks, that Africa had tribes with no heads at all—just eyes and mouths in their breasts—and that the Caribbean was peopled by cannibals, amazons and giants. Some believed that the oceans were full of strange creatures such as mermaids and sea dragons. In 1583 Sir Henry Gilbert professed to have encountered a lion-like sea monster on his return from claiming St. John’s, Newfoundland, for England. In a world that was as yet so immeasurable, frightening and inexplicable, George and his fellow travellers must have feared that they were not just crossing the map, but falling off the edge of it.

Yet by the seventeenth century, many thousands of Britons, beguiled by the much-vaunted possibilities of the “New World” (which they saw as a tabula rasa on which they could write, despite the long history and complex cultures long implanted there), were willing to take that leap into the unknown, and left their homeland to start a fresh life in the Americas. The migration had begun as a trickle in 1607 with the settling of Jamestown, the first permanent colony in what is now the United States. It had increased to a recognizable stream by 1629 and became a veritable flood in the 1640s, when over 100,000 people left a country with a population of just under five million. (Between 1600 and 1700 over 700,000 people emigrated from England, about 17 per cent of the English population in 1600.) At the rate of one ship departing from England every day, these pioneers arrived to “settle the Americas,” fanning out from Newfoundland for three thousand miles, via Virginia and the Caribbean, to Guiana on the South American mainland. All the way they fought, worked and died to establish themselves in new and terrifying lands.

The English weren’t the only nation on the move. The Spanish were the pioneers of colonization of the Americas, and the Portuguese, French and Dutch swiftly became essential players in the region. But just over a century after Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World (which the historian Germán Arciniegas described as being “so momentous a development in human history that it was like the passing from the third to the fourth day in the first chapter of Genesis”), it was the small nation of England that emerged as Europe’s greatest colonizing power. This was particularly surprising for a people who were “wedded to their native Soile like a Snaile to his shell.” What motivated these patriotic and insular people to abandon the world as they knew it and move halfway across the globe?

The why of George Ashby’s departure is something I will never know; my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather was most likely typical of the men who settled much of the New World, a man of action, not reflection, who did not take time out to write letters or keep journals; nor was he important enough for others to write about him. But certainly some of the wider reasons that stirred migrants to risk the New World would have applied to him. Historians have summarized Europe’s motivation for the conquest of the Americas with the pithy phrase “God, gold and glory.” This formula is slightly reductive—and certainly doesn’t allow for the large number of migrants who had no say in their transfer—but it does convey the positive pull of the opportunities represented by the New World.

It was not only the much-persecuted Puritans who went to settle New England for whom God was important. The vast majority of those who migrated to colonies south of Maryland were what the historian Carl Bridenbaugh has dubbed “non-separating puritans.” They may not have moved together as a religious community led by a minister, but they did share the Puritans’ profound unease with the old ways of worship and were questioning of the ancient, ceremonial doctrines of the established church. They too had looked on at the risible spectacle of “the typical Sunday service in England, where parishioners stared dumbly at a minister mumbling incomprehensible phrases from the Book of Common Prayer” and recognized “how far most people were from a true engagement with the word of God.” So while they had not been impassioned enough to make their faith the prime motivation for their migration, their religious leanings meant that they were that bit more likely to be disillusioned—and therefore to contemplate migration—than their fellow Englishmen.

The Bible was, in fact, a potent recruiter for colonization. In an age where the scriptures permeated everyday life, there were numerous passages that would have resonated with those tempted by the “Western Star.” Great orators such as the Anglican priest Robert Gray, or John Donne, the Dean of St. Paul’s, or the Puritan preachers Thomas Hooker and John Cotton thundered from Genesis: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee: And I will make of thee a great nation,” or from II Samuel 7:10: “I will appoint a place for my people Israel, and will plant them, that they may dwell in a place of their own, and move no more: neither shall the children of wickedness afflict them any more, as beforetime.”

The dream of building a City on the Hill for the perfection of the human spirit, so inspirational to the Puritans, was also an attractive one for many other migrants, as was the entire project of spreading the word. Captain John Smith, the era’s most famous adventurer turned planter, declared:

If hee have any graine of faith or zeale in Religion, what can he doe less hurtfull to any, or more agreeable to God, then to seeke to convert those poore Savages to know Christ and humanity, whose labours with discretion will triple requite thy charge and paine; what so truly sutes with honour and honesty, as the discovering things unknowne, erecting Townes, peopling Countries, informing the ignorant, reforming things unjust, teaching vertue and gaine to our native mother Country a Kingdome to attend her.

But rhetoric about taking Christianity and civilization to the heathen (so lavishly exploited by the Spanish conquistadors), or giving European creativity and imagination space to grow, was a smokescreen for the economic imperatives that drove the majority of migrants. They hungered for gold; or at least the chance to acquire land, their own little piece of paradise.

Most seventeenth-century English émigrés were in flight from terrible poverty. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, rapid population growth and periodic agricultural depression, culminating in a series of terrible famines, caused genuine hardship. In the countryside large numbers of people had been deprived of their ancient rural security. The lack of land to cultivate frustrated many, while unemployment threatened agricultural labourers as well as village artisans. The rise in the cost of living and the simultaneous fall in the value of wages meant that many people were surviving on the very margins of existence. Housing was inadequate at best; in cold or wet weather fuel was scarce and expensive. Health scares were frequent, with regular outbreaks of tuberculosis and plague. Effective medical treatment was almost non-existent and so the mortality rate—already high—rose even higher.

Resentment against these conditions focused and crystallized on a lavish, self-indulgent monarch: Charles I. His resistance to parliamentary challenge meant that, from 1629, the people had been governed by arbitrary monarchical rule. His decision to levy various taxes to obtain revenue and his exploitation of press-gangs who forced unwilling souls into the navy, meant greater financial strain for his already beleaguered subjects and generated a real sense of bitterness. (“Thus was the king’s coffers filled with oppression,” concluded one pamphlet in 1649.) His popularity was eroded further by his religious affiliations: not only had he displayed a preference for the High Anglican worship that would so alienate the Puritans and others of that ilk, he had also married a Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria, and allowed her to observe her faith publicly.

The wider political situation also contributed to the depressed mood of the country and the general suffering endured during this period. The Thirty Years War (1618ߝ48), which had seen warring Protestant and Catholic forces reduce much of Europe to a corpse-strewn battleground, further depleted the nation and contributed to profound collective dissatisfaction with the status quo. The decades from the 1630s through to the end of the 1650s were, according to the historian Peter Bowden, “probably amongst the most terrible years through which the country had ever passed.” He goes on: “It is probably no coincidence that the first real beginnings of the colonisation of America dated from this period.” Facing poverty, hunger and actual starvation at home, the populace were more than usually attentive to the pedlars of tales told in taverns of the lands across the sea, where everyone could have a full belly and their own property.

One such economic migrant was Richard Ligon. A cultured, educated gentleman of “above sixty years” who had served at Charles I’s court, he sailed for Barbados in 1647. Ligon was untypical of most migrants to the Caribbean by virtue of his age and class. But his reasons for migrating—essentially economic—would have resonated with most of his contemporaries. Though in the “last scene of my life,” he had “lost (by a Barbarous Riot) all I had gotten by the painful travels and cares of my youth . . . and left destitute of a subsistence.” In this desperate condition he looked about for friends to support him, found none, and therefore considered himself “a stranger in my own Countrey.” As a result, he “resolv’d to lay on the first opportunity that might convey me to any other part of the World, how far distant soever, rather than abide here.”

There was a wind over England, and it blew.

(Have you heard the news of Virginia?)

A west wind blowing, the wind of a western star,

To gather men’s lives like pollen and cast them forth,

Blowing in hedge and highway and seaport town,

Whirling dead leaf and living but always blowing,

A salt wind, a sea wind, a wind from the world’s end,

From the coasts that have new wild names, from the huge unknown.

—stephen vincent benét, “western star”

george ashby’s story began as all migrants’ stories do: with a journey.

Some time in the late 1630s, when George Ashby was finally given notification that his ship was ready to sail, he must have been afraid. He was a blacksmith, a young man in his late teens, about to leave behind everything he had ever known. Though the voyage carried the seeds of his dreams he, like most of the population, had probably never undergone a long sea journey before and had no real idea of what to expect when he arrived in the Americas.

Those who chose to undertake the fearsome Atlantic crossing in search of a new life were generally tough—or else dangerously foolish. But what else can we know about George Ashby, my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather? Was he fleeing from a family or seeking a new one? Did he dream of religious freedom or of wealth? Was he ambivalent about leaving his homeland or were his life experiences so bitter that he believed nothing in the Americas could be worse? As he set sail for the adventuresome world of the Caribbean he would have had no idea how heavily the odds were stacked against him. (According to one historian, men like him were “pursuing a will-o’-the-wisp,” since very few of them ever achieved the better life they longed for.) He could not know that he would be one of the lucky ones: that he would not just survive but found a dynasty that endures to this day, built on sugar and forged by slavery.

The first sight of the ship would have done nothing to allay his trepidation. The typical merchant vessel that plied the route between the Caribbean and Britain was rated at around 200 tons (meaning that it could accommodate 200 casks or tuns of wine). Trussed against the stone walls of the dock, the ship looked like a gigantic gutted carcass afloat upon the water. The gaunt ribs of the wooden hull curved menacingly into the sky and the base was coated with a shaggy pelt of seaweed and barnacles. It would have been hard for George to countenance that he would be confined in the belly of this behemoth for almost two months, with the real possibility that his journey would end, like that of so many before him, in massacre by pirates or drowning at sea.

After unpacking and settling in, the passengers were summoned on deck to present their documents to the “searchers.” These officials administered the oath of allegiance to the king, stamped each traveller’s ticket with the crucial “Licences under their hands and seals to pass the seas,” and then cleared the vessel for departure. Since every passenger had to undergo this process, no matter what their individual circumstances or where they came from, it represented their first rite of passage, one that made their new status as migrants starkly real.

Still gathered on the bridge, the passengers chatted among themselves or waved to family and friends gathered portside to wish them bon voyage. Then, all of a sudden, a flurry of activity: the sailors scrambling across the deck, busying themselves with a series of tasks that were inexplicable to most of the passengers, the screeching of the anchor as it was winched aboard, the screaming of the hoisted sails, the shouting of the master and the sailors, all combined in a violent auditory assault. As the crew worked furiously in the bows, stern and dock, the passengers jostled to be as near the rails as possible.

Despite the noise and bustle of the ship, most of the migrants would have been as hushed as worshippers in a church, fearful of what the voyage might hold or trying to imagine what lay at the other end. They were aware that the journey was, in all probability, final. Some may have dreamt of returning to their homeland enriched, perhaps even ennobled, but most rightly sensed that they would not be coming back.

To truly grasp what this sea journey meant, what bravery and audacity it required, one must understand how the world was seen and known at that time. Though George Ashby and his contemporaries had been born in the Age of Discovery (1500ߝ1700), most of the world was still terra incognita for Europeans. Maps were often sketchy and inaccurate. Two continents, Australia and Antarctica, had not been traced at all, and vast areas were still blank. The interiors of South America, Africa and Asia had scarcely been explored. Beyond the eastern fringe of North America, which George’s fellow pioneers had begun to document, were millions of square miles of uncharted wilderness.

Like many other countries in the Old World, England was poised between the medieval and the modern, where most people’s lives played out within a narrow radius around their birthplace, and their beliefs were characterized by superstition and ignorance. It was an age in which magic still played a large part in the lives of ordinary people and many firmly believed in witches and fairies, that butterflies were the souls of the dearly departed, and that churchyards swarmed with souls and spirits. In the absence of real information about far-off lands, fantasies abounded: that the east was populated with dog-headed men and basilisks, that Africa had tribes with no heads at all—just eyes and mouths in their breasts—and that the Caribbean was peopled by cannibals, amazons and giants. Some believed that the oceans were full of strange creatures such as mermaids and sea dragons. In 1583 Sir Henry Gilbert professed to have encountered a lion-like sea monster on his return from claiming St. John’s, Newfoundland, for England. In a world that was as yet so immeasurable, frightening and inexplicable, George and his fellow travellers must have feared that they were not just crossing the map, but falling off the edge of it.

Yet by the seventeenth century, many thousands of Britons, beguiled by the much-vaunted possibilities of the “New World” (which they saw as a tabula rasa on which they could write, despite the long history and complex cultures long implanted there), were willing to take that leap into the unknown, and left their homeland to start a fresh life in the Americas. The migration had begun as a trickle in 1607 with the settling of Jamestown, the first permanent colony in what is now the United States. It had increased to a recognizable stream by 1629 and became a veritable flood in the 1640s, when over 100,000 people left a country with a population of just under five million. (Between 1600 and 1700 over 700,000 people emigrated from England, about 17 per cent of the English population in 1600.) At the rate of one ship departing from England every day, these pioneers arrived to “settle the Americas,” fanning out from Newfoundland for three thousand miles, via Virginia and the Caribbean, to Guiana on the South American mainland. All the way they fought, worked and died to establish themselves in new and terrifying lands.

The English weren’t the only nation on the move. The Spanish were the pioneers of colonization of the Americas, and the Portuguese, French and Dutch swiftly became essential players in the region. But just over a century after Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World (which the historian Germán Arciniegas described as being “so momentous a development in human history that it was like the passing from the third to the fourth day in the first chapter of Genesis”), it was the small nation of England that emerged as Europe’s greatest colonizing power. This was particularly surprising for a people who were “wedded to their native Soile like a Snaile to his shell.” What motivated these patriotic and insular people to abandon the world as they knew it and move halfway across the globe?

The why of George Ashby’s departure is something I will never know; my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather was most likely typical of the men who settled much of the New World, a man of action, not reflection, who did not take time out to write letters or keep journals; nor was he important enough for others to write about him. But certainly some of the wider reasons that stirred migrants to risk the New World would have applied to him. Historians have summarized Europe’s motivation for the conquest of the Americas with the pithy phrase “God, gold and glory.” This formula is slightly reductive—and certainly doesn’t allow for the large number of migrants who had no say in their transfer—but it does convey the positive pull of the opportunities represented by the New World.

It was not only the much-persecuted Puritans who went to settle New England for whom God was important. The vast majority of those who migrated to colonies south of Maryland were what the historian Carl Bridenbaugh has dubbed “non-separating puritans.” They may not have moved together as a religious community led by a minister, but they did share the Puritans’ profound unease with the old ways of worship and were questioning of the ancient, ceremonial doctrines of the established church. They too had looked on at the risible spectacle of “the typical Sunday service in England, where parishioners stared dumbly at a minister mumbling incomprehensible phrases from the Book of Common Prayer” and recognized “how far most people were from a true engagement with the word of God.” So while they had not been impassioned enough to make their faith the prime motivation for their migration, their religious leanings meant that they were that bit more likely to be disillusioned—and therefore to contemplate migration—than their fellow Englishmen.

The Bible was, in fact, a potent recruiter for colonization. In an age where the scriptures permeated everyday life, there were numerous passages that would have resonated with those tempted by the “Western Star.” Great orators such as the Anglican priest Robert Gray, or John Donne, the Dean of St. Paul’s, or the Puritan preachers Thomas Hooker and John Cotton thundered from Genesis: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee: And I will make of thee a great nation,” or from II Samuel 7:10: “I will appoint a place for my people Israel, and will plant them, that they may dwell in a place of their own, and move no more: neither shall the children of wickedness afflict them any more, as beforetime.”

The dream of building a City on the Hill for the perfection of the human spirit, so inspirational to the Puritans, was also an attractive one for many other migrants, as was the entire project of spreading the word. Captain John Smith, the era’s most famous adventurer turned planter, declared:

If hee have any graine of faith or zeale in Religion, what can he doe less hurtfull to any, or more agreeable to God, then to seeke to convert those poore Savages to know Christ and humanity, whose labours with discretion will triple requite thy charge and paine; what so truly sutes with honour and honesty, as the discovering things unknowne, erecting Townes, peopling Countries, informing the ignorant, reforming things unjust, teaching vertue and gaine to our native mother Country a Kingdome to attend her.

But rhetoric about taking Christianity and civilization to the heathen (so lavishly exploited by the Spanish conquistadors), or giving European creativity and imagination space to grow, was a smokescreen for the economic imperatives that drove the majority of migrants. They hungered for gold; or at least the chance to acquire land, their own little piece of paradise.

Most seventeenth-century English émigrés were in flight from terrible poverty. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, rapid population growth and periodic agricultural depression, culminating in a series of terrible famines, caused genuine hardship. In the countryside large numbers of people had been deprived of their ancient rural security. The lack of land to cultivate frustrated many, while unemployment threatened agricultural labourers as well as village artisans. The rise in the cost of living and the simultaneous fall in the value of wages meant that many people were surviving on the very margins of existence. Housing was inadequate at best; in cold or wet weather fuel was scarce and expensive. Health scares were frequent, with regular outbreaks of tuberculosis and plague. Effective medical treatment was almost non-existent and so the mortality rate—already high—rose even higher.

Resentment against these conditions focused and crystallized on a lavish, self-indulgent monarch: Charles I. His resistance to parliamentary challenge meant that, from 1629, the people had been governed by arbitrary monarchical rule. His decision to levy various taxes to obtain revenue and his exploitation of press-gangs who forced unwilling souls into the navy, meant greater financial strain for his already beleaguered subjects and generated a real sense of bitterness. (“Thus was the king’s coffers filled with oppression,” concluded one pamphlet in 1649.) His popularity was eroded further by his religious affiliations: not only had he displayed a preference for the High Anglican worship that would so alienate the Puritans and others of that ilk, he had also married a Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria, and allowed her to observe her faith publicly.

The wider political situation also contributed to the depressed mood of the country and the general suffering endured during this period. The Thirty Years War (1618ߝ48), which had seen warring Protestant and Catholic forces reduce much of Europe to a corpse-strewn battleground, further depleted the nation and contributed to profound collective dissatisfaction with the status quo. The decades from the 1630s through to the end of the 1650s were, according to the historian Peter Bowden, “probably amongst the most terrible years through which the country had ever passed.” He goes on: “It is probably no coincidence that the first real beginnings of the colonisation of America dated from this period.” Facing poverty, hunger and actual starvation at home, the populace were more than usually attentive to the pedlars of tales told in taverns of the lands across the sea, where everyone could have a full belly and their own property.

One such economic migrant was Richard Ligon. A cultured, educated gentleman of “above sixty years” who had served at Charles I’s court, he sailed for Barbados in 1647. Ligon was untypical of most migrants to the Caribbean by virtue of his age and class. But his reasons for migrating—essentially economic—would have resonated with most of his contemporaries. Though in the “last scene of my life,” he had “lost (by a Barbarous Riot) all I had gotten by the painful travels and cares of my youth . . . and left destitute of a subsistence.” In this desperate condition he looked about for friends to support him, found none, and therefore considered himself “a stranger in my own Countrey.” As a result, he “resolv’d to lay on the first opportunity that might convey me to any other part of the World, how far distant soever, rather than abide here.”