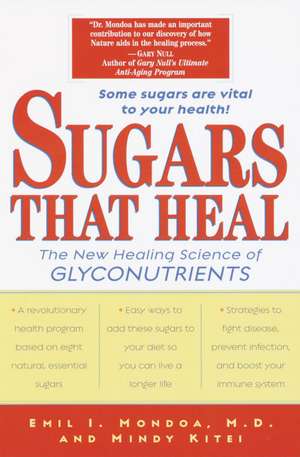

Sugars That Heal: The New Healing Science of Glyconutrients

Autor Emil I. Mondoa, Mindy Kiteien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2002

As medical doctor and scientific researcher Emil Mondoa explains, these eight essential sugars, known as saccharides, are the basis of multicellular intelligence--the ability of cells to communicate, cohere, and work together to keep us healthy and balanced. Even tiny amounts of these sugars--or lack of them--have profound effects. In test after test conducted at leading institutes around the world, saccharides have been shown to lower cholesterol, increase lean muscle mass, decrease body fat, accelerate wound healing, ease allergy symptoms, and allay autoimmune diseases such as arthritis, psoriasis, and diabetes. Bacterial infections, including the recurrent ear infections that plague toddlers, often respond remarkably to saccharides, as do many viruses--from the common cold to the flu, from herpes to HIV. The debilitating symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and Gulf War syndrome frequently abate after adding saccharides. And, for cancer patients, saccharides mitigate the toxic effects of radiation and chemotherapy--while augmenting their cancer-killing effects, resulting in prolonged survival and improved quality of life.

Sugars That Heal offers a revolutionary new health plan based on the science of glyconutrients--foods that contain saccharides. It gives authoritative guidance for getting all eight saccharides conveniently into your diet through supplements and readily available foods, as well as detailed information on correct dosages. Here, too, are chapters dealing with the special nutritional needs of people suffering from cancer, heart disease, asthma, and neurological disorders, and methods for using glyconutrients to treat depression, obesity, and ADHD.

The more doctors learn about glyconutrients, the more excited they become about their long-term fundamental health benefits. Now, with this new book, the breakthroughs in the study of glyconutrients are available to everyone. Whether your goal is to prevent disease, live longer and better, or treat a serious illness that has eluded conventional medicine, Sugars That Heal is your essential guide to complete health.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 106.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.45€ • 21.08$ • 17.27£

20.45€ • 21.08$ • 17.27£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345441072

ISBN-10: 0345441079

Pagini: 282

Dimensiuni: 139 x 209 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0345441079

Pagini: 282

Dimensiuni: 139 x 209 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Emil I. Mondoa, M.D., is a practicing, board-certified pediatrician affiliated with Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center in Camden, New Jersey; South Jersey Medical Center in Vineland, New Jersey; and the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Delaware. He also holds an MBA from the Wharton School, with a focus on health-care management. He is founder of the Glyconutrients Research Foundation.

Mindy Kitei is an editor, writer, and instructor who works in Philadelphia. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, she is a former editor at TV Guide and Philadelphia Magazine. She has taught journalism at Temple University and Rosemont College.

From the Hardcover edition.

Mindy Kitei is an editor, writer, and instructor who works in Philadelphia. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, she is a former editor at TV Guide and Philadelphia Magazine. She has taught journalism at Temple University and Rosemont College.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

PART I

What Are Saccharides and Why Are They Important?

“It is not . . . that some people do not know what to do with truth when it is offered them, but the tragic fate is to reach, after patient search, a condition of mind-blindness, in which the truth is not recognized, though it stares you in the face.” —Sir William Osler, physician, 1849–1919

Chapter 1

Coley’s Saccharides

Though he didn’t know why they worked, more than a hundred years ago a Harvard-educated physician named William Coley figured out that saccharides could cure certain cancers.

In the fall of 1890, Elizabeth Dashiell, a delicate young woman of seventeen, was diagnosed with bone cancer in her right hand. Since her diagnosis had come early in the course of the disease, amputation of her afflicted arm below the elbow was swift. Yet she died a few months later. Her doctor, twenty-eight-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate William Coley, was distraught. A surgeon at New York’s Memorial Hospital, which would later be renamed Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Coley began poring over old patient records—for what, he wasn’t sure. As Coley read the dusty charts, he saw that most cancer therapies failed; most of the patients died. But curiously, one patient who was severely afflicted with sarcoma, a cancer of the connective tissue, did recuperate.1, 2 Hospitalized and near death in the fall of 1884, he experienced two outbreaks of a severe skin infec- tion called erysipelas. Caused by a strep bacterium, the infections resulted in high fevers and roused his immune system. The bumpy, plum-sized tumor below his left ear began to shrink and the patient rallied, recovering completely. When the tenacious Coley tracked the man down, he was well, with no cancer recurrence some seven years later.

Because Coley’s discovery transpired more than a century ago when the immune system was uncharted territory, the scientist didn’t understand how the patient’s strep infection could bring about a cancer remission. Nevertheless, the prescient physician thought perhaps he had stumbled across something important—a novel way to treat cancer—and began a series of experiments on sarcoma patients.3 Coley’s quest to reproduce what nature had so elegantly accomplished is detailed with heart-thumping vigor by writer Stephen Hall in his excellent book A Commotion in the Blood.4 According to Hall, after repeated failures in inoculating a sarcoma patient with live cultures of the strep bacterium, Coley eventually procured an exceptionally potent strain that induced a high fever and skin infection in the lucky man who received it. Within a few weeks the patient’s neck tumors be- gan to recede, eventually vanished, and didn’t return for several years—and the young surgeon soon published his first paper.

Using live, virulent bacteria was, naturally, dangerous (in fact, two of Coley’s patients died from resulting step infections), so the doctor eventually developed a safer method, devising a vaccine. After culturing the bacteria, Coley killed the colonies or filtered them out, his theory being that the toxins the cultured bacteria had produced were at least partly responsible for the tumor shrinkage.5 In due course, Coley added the toxins from a second bacterium, which today is called Serratia marcescens. That combination proved remarkably successful. On advanced, inoperable sarcomas he accomplished a cure rate of close to 20 percent with his treatment. When the toxin therapy was continued for six months after surgery, Coley’s five-year remission rates soared to 80 percent, according to a retrospective study done by Coley’s daughter.6 That figure rivals, and in some cases surpasses, current sarcoma treatment outcomes, without the long-term consequences of today’s chemotherapies and radiation.

For a short time, Coley’s toxins—also known as fever therapy because the treatment induced high fevers—was the only recognized systemic treatment for cancer other than surgery. Coley’s crude bacterial immunotherapy, however, was never really accepted in scientific circles. Quality control was one reason. The toxins weren’t standardized, nor was the dosing, and many physicians with inferior batches didn’t get good results.7, 8 In addition, vaccine therapy wasn’t a top priority for pharmaceutical companies. There wasn’t then, and there isn’t now, much money in it. And since turn-of-the century medicine had no understanding of the immune system, scientists lacked the framework for understanding why the toxins worked.9 The final demise of toxin therapy came with the advent of radiation therapy.

At first, physicians often used the two therapies together. But as writer Stephen Hall explains, radiation became so fashionable that Coley’s overzealous boss, the then-head of Memorial Hospital, Dr. James Ewing, advised his staff to use high-dose radiation not only for bone cancer but also for all instances of “persistent unexplained” bone pain.10 Meanwhile, Coley’s toxins became yesterday’s news, even though the treatment appeared to work better than radiation. Of twenty-four patients with inoperable sarcoma at Memorial Hospital treated with radiation alone, twenty-one were dead and the other three had had treatment too recent to evaluate.11 In contrast, of twenty-two inoperable sarcoma cases treated with Coley’s toxins, some in conjunction with radiation, some not, twelve patients remained cancer-free after five years, the benchmark for a clinical cure.12

Damn the statistics—radium was, in a word, hot, and Coley’s toxins were not. Like lambs to the slaughter, the unsuspecting public joined the radium craze on an unregulated, recreational level. Dubbed “mild radium therapy” to distinguish it from the high radium levels reserved for cancer treatment, over-the-counter radium-enhanced products became de rigueur.13 Radium foot salves were up-to-the-minute at the turn of the century; for men only, a radium-fortified jockstrap was available. Manufacturers laced candy with radium and spiked designer water called Radithor with it, touting the one-dollar-a-bottle brew as an energy elixir for 150 “endocrinologic” ailments, from rheumatism and hypertension to exhaustion and sexual dysfunction.14, 15 Indeed, the doctor’s pamphlet that accompanied Radithor boasted that its “tonic effects upon the nervous system generally result in a great improvement in the sex organs.”16 Not surprisingly, more than 400,000 bottles were sold.

Recreational radium finally lost its luster soon after forty-seven-year-old Pittsburgh playboy, steel tycoon and former amateur golf champion Eben M. Byers, on his doctor’s advice, began imbibing Radithor daily to nurse an arm injury. Invigorated, he tripled his dose but gradually began feeling tired and losing weight. By the time he figured out why, it was too late. The toothless Food and Drug Administration(FDA) at the time could only issue warnings. Not so for the Federal Trade Commission(FTC). In a surreal twist, the FTC at first took action against those radium elixirs that failed to meet their advertised levels of radium.17

As for Byers, the radium had dissolved much of his upper and lower jaws in short order and bored holes in his skull, caus- ing pain and disfigurement. “The Radium Water Worked Fine Until His Jaw Came Off” proclaimed the blunt Wall Street Journal headline, curtly summing up Eben Byers’s disastrous experience with Radithor.18 The once rakish, robust industrialist was a timeworn, shrunken 92 pounds fading into the starched white sheets at Doctors’ Hospital in New York City, where he died at age fifty-one on March 31, 1932, and made front-page news.19 A few months before, the FTC had stepped in and put a stop to Radithor, and before long the FDA was regulating the chemical element.

Astonishingly, Byers’s death didn’t taint the use of high-dose radiation—perhaps because with Coley’s toxins passé, there were no other cancer-treatment options at the time besides surgery. After Coley’s death in 1936, his immunotherapy plunged from outré to oblivion.

Then, in 1943, a scientist at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) discovered that a lipopolysaccharide—a fat bonded to a saccharide, the scientific word for sugar—was the biologically active substance in the toxins of Serratia marcescens, one of the components of Coley’s vaccine. In this case, the lipopolysaccharides resided in the cell walls of the Serratia marcescens bacteria. The fat in the lipopolysaccharide could cause toxicity problems, however; scientists eventually pared the fat from the sugar, leaving a nontoxic compound with salutary immune-system effects. These compounds incite the body to stimulate the immune cells and produce proteins called cytokines, which make you feel achy and fluish as they do battle with pathogens loitering in their path.20, 21

Unfortunately, the NCI discovery did nothing to resurrect the popularity of Coley’s therapy. In fact, in 1965, in a mind-boggling move, the American Cancer Society added Coley’s toxins to its list of “unproven” cancer drugs, in essence pronouncing his invention quackery, along with the likes of coffee enemas and laetrile.22 Although the pronouncement was lifted ten years later, the bad publicity had sealed the fate of this undervalued treatment in the United States.

Vaccine therapy, however, remained popular in other countries. German scientists continued with their research, as did the Chinese. Bacterial vaccines have been most effective for sarcomas, lymphomas, and melanomas. Coley’s vaccine has yielded impressive results, but thanks to one hundred years of scientific inertia, politics, and greed propagated by an unwitting confederacy of dunces, it’s still not an established treatment for cancer. In all probability Coley’s vaccine never will be because you can’t patent a century-old drug.

Many discoveries of the first rank are for a time ignored or ridiculed. (Conversely, many discoveries, like radiation therapy, are for a time overrated.) What happened to the discovery of William Coley, who died largely forgotten and broke, having lost his money in the stock market crash of 1929, was, sadly, nothing new. What was new, though Coley didn’t know it at the time, was that he made the first scientific association between the immune system and saccharides, the sugars that heal.

As an early indication of saccharides’ worth, Coley’s toxins are just the tip of the iceberg. In the past twenty years, the amount of information garnered about these sugars has increased dramatically. Of the more than two hundred sugars, eight are essential to optimal body functioning. Far more than just a ready source of fuel for the cells, these eight essential sugars have potent antiviral, antibacterial, antiparasitic, and of course antitumor effects.23

Essential saccharides have also been shown in clinical trials to reduce allergies and to allay symptoms in such chronic diseases as arthritis, diabetes, lupus, and kidney disease. They accel- erate the healing of burns and wounds and help heal skin conditions—from poison ivy to psoriasis. They increase the body’s resistance to viruses, including those that cause the common cold, influenza, herpes, and hepatitis. They quell the recurrent bacterial ear infections that plague toddlers and children. Some people with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War syndrome, and HIV have reported improvement in their symptoms when they supplement their diet with these simple sugars.

The Eight Essential Saccharides

When most of us think of sugar, we think only of table sugar from sugarcane, which consists of two saccharides, glucose and fructose. The eight essential saccharides our bodies need are mannose, glucose, galactose, xylose, fucose (not to be confused with fructose), N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, and N-acetylneuraminic acid. These eight essential saccharides compose the main focus of Sugars That Heal. Only two of these essential sugars, glucose (found in plants and table sugar) and galactose (found in milk products and certain pectins), are common in our diets. Although fructose, found in fruits and table sugar, is also a part of most diets, it’s not an essential saccharide.

From the Hardcover edition.

What Are Saccharides and Why Are They Important?

“It is not . . . that some people do not know what to do with truth when it is offered them, but the tragic fate is to reach, after patient search, a condition of mind-blindness, in which the truth is not recognized, though it stares you in the face.” —Sir William Osler, physician, 1849–1919

Chapter 1

Coley’s Saccharides

Though he didn’t know why they worked, more than a hundred years ago a Harvard-educated physician named William Coley figured out that saccharides could cure certain cancers.

In the fall of 1890, Elizabeth Dashiell, a delicate young woman of seventeen, was diagnosed with bone cancer in her right hand. Since her diagnosis had come early in the course of the disease, amputation of her afflicted arm below the elbow was swift. Yet she died a few months later. Her doctor, twenty-eight-year-old Harvard Medical School graduate William Coley, was distraught. A surgeon at New York’s Memorial Hospital, which would later be renamed Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Coley began poring over old patient records—for what, he wasn’t sure. As Coley read the dusty charts, he saw that most cancer therapies failed; most of the patients died. But curiously, one patient who was severely afflicted with sarcoma, a cancer of the connective tissue, did recuperate.1, 2 Hospitalized and near death in the fall of 1884, he experienced two outbreaks of a severe skin infec- tion called erysipelas. Caused by a strep bacterium, the infections resulted in high fevers and roused his immune system. The bumpy, plum-sized tumor below his left ear began to shrink and the patient rallied, recovering completely. When the tenacious Coley tracked the man down, he was well, with no cancer recurrence some seven years later.

Because Coley’s discovery transpired more than a century ago when the immune system was uncharted territory, the scientist didn’t understand how the patient’s strep infection could bring about a cancer remission. Nevertheless, the prescient physician thought perhaps he had stumbled across something important—a novel way to treat cancer—and began a series of experiments on sarcoma patients.3 Coley’s quest to reproduce what nature had so elegantly accomplished is detailed with heart-thumping vigor by writer Stephen Hall in his excellent book A Commotion in the Blood.4 According to Hall, after repeated failures in inoculating a sarcoma patient with live cultures of the strep bacterium, Coley eventually procured an exceptionally potent strain that induced a high fever and skin infection in the lucky man who received it. Within a few weeks the patient’s neck tumors be- gan to recede, eventually vanished, and didn’t return for several years—and the young surgeon soon published his first paper.

Using live, virulent bacteria was, naturally, dangerous (in fact, two of Coley’s patients died from resulting step infections), so the doctor eventually developed a safer method, devising a vaccine. After culturing the bacteria, Coley killed the colonies or filtered them out, his theory being that the toxins the cultured bacteria had produced were at least partly responsible for the tumor shrinkage.5 In due course, Coley added the toxins from a second bacterium, which today is called Serratia marcescens. That combination proved remarkably successful. On advanced, inoperable sarcomas he accomplished a cure rate of close to 20 percent with his treatment. When the toxin therapy was continued for six months after surgery, Coley’s five-year remission rates soared to 80 percent, according to a retrospective study done by Coley’s daughter.6 That figure rivals, and in some cases surpasses, current sarcoma treatment outcomes, without the long-term consequences of today’s chemotherapies and radiation.

For a short time, Coley’s toxins—also known as fever therapy because the treatment induced high fevers—was the only recognized systemic treatment for cancer other than surgery. Coley’s crude bacterial immunotherapy, however, was never really accepted in scientific circles. Quality control was one reason. The toxins weren’t standardized, nor was the dosing, and many physicians with inferior batches didn’t get good results.7, 8 In addition, vaccine therapy wasn’t a top priority for pharmaceutical companies. There wasn’t then, and there isn’t now, much money in it. And since turn-of-the century medicine had no understanding of the immune system, scientists lacked the framework for understanding why the toxins worked.9 The final demise of toxin therapy came with the advent of radiation therapy.

At first, physicians often used the two therapies together. But as writer Stephen Hall explains, radiation became so fashionable that Coley’s overzealous boss, the then-head of Memorial Hospital, Dr. James Ewing, advised his staff to use high-dose radiation not only for bone cancer but also for all instances of “persistent unexplained” bone pain.10 Meanwhile, Coley’s toxins became yesterday’s news, even though the treatment appeared to work better than radiation. Of twenty-four patients with inoperable sarcoma at Memorial Hospital treated with radiation alone, twenty-one were dead and the other three had had treatment too recent to evaluate.11 In contrast, of twenty-two inoperable sarcoma cases treated with Coley’s toxins, some in conjunction with radiation, some not, twelve patients remained cancer-free after five years, the benchmark for a clinical cure.12

Damn the statistics—radium was, in a word, hot, and Coley’s toxins were not. Like lambs to the slaughter, the unsuspecting public joined the radium craze on an unregulated, recreational level. Dubbed “mild radium therapy” to distinguish it from the high radium levels reserved for cancer treatment, over-the-counter radium-enhanced products became de rigueur.13 Radium foot salves were up-to-the-minute at the turn of the century; for men only, a radium-fortified jockstrap was available. Manufacturers laced candy with radium and spiked designer water called Radithor with it, touting the one-dollar-a-bottle brew as an energy elixir for 150 “endocrinologic” ailments, from rheumatism and hypertension to exhaustion and sexual dysfunction.14, 15 Indeed, the doctor’s pamphlet that accompanied Radithor boasted that its “tonic effects upon the nervous system generally result in a great improvement in the sex organs.”16 Not surprisingly, more than 400,000 bottles were sold.

Recreational radium finally lost its luster soon after forty-seven-year-old Pittsburgh playboy, steel tycoon and former amateur golf champion Eben M. Byers, on his doctor’s advice, began imbibing Radithor daily to nurse an arm injury. Invigorated, he tripled his dose but gradually began feeling tired and losing weight. By the time he figured out why, it was too late. The toothless Food and Drug Administration(FDA) at the time could only issue warnings. Not so for the Federal Trade Commission(FTC). In a surreal twist, the FTC at first took action against those radium elixirs that failed to meet their advertised levels of radium.17

As for Byers, the radium had dissolved much of his upper and lower jaws in short order and bored holes in his skull, caus- ing pain and disfigurement. “The Radium Water Worked Fine Until His Jaw Came Off” proclaimed the blunt Wall Street Journal headline, curtly summing up Eben Byers’s disastrous experience with Radithor.18 The once rakish, robust industrialist was a timeworn, shrunken 92 pounds fading into the starched white sheets at Doctors’ Hospital in New York City, where he died at age fifty-one on March 31, 1932, and made front-page news.19 A few months before, the FTC had stepped in and put a stop to Radithor, and before long the FDA was regulating the chemical element.

Astonishingly, Byers’s death didn’t taint the use of high-dose radiation—perhaps because with Coley’s toxins passé, there were no other cancer-treatment options at the time besides surgery. After Coley’s death in 1936, his immunotherapy plunged from outré to oblivion.

Then, in 1943, a scientist at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) discovered that a lipopolysaccharide—a fat bonded to a saccharide, the scientific word for sugar—was the biologically active substance in the toxins of Serratia marcescens, one of the components of Coley’s vaccine. In this case, the lipopolysaccharides resided in the cell walls of the Serratia marcescens bacteria. The fat in the lipopolysaccharide could cause toxicity problems, however; scientists eventually pared the fat from the sugar, leaving a nontoxic compound with salutary immune-system effects. These compounds incite the body to stimulate the immune cells and produce proteins called cytokines, which make you feel achy and fluish as they do battle with pathogens loitering in their path.20, 21

Unfortunately, the NCI discovery did nothing to resurrect the popularity of Coley’s therapy. In fact, in 1965, in a mind-boggling move, the American Cancer Society added Coley’s toxins to its list of “unproven” cancer drugs, in essence pronouncing his invention quackery, along with the likes of coffee enemas and laetrile.22 Although the pronouncement was lifted ten years later, the bad publicity had sealed the fate of this undervalued treatment in the United States.

Vaccine therapy, however, remained popular in other countries. German scientists continued with their research, as did the Chinese. Bacterial vaccines have been most effective for sarcomas, lymphomas, and melanomas. Coley’s vaccine has yielded impressive results, but thanks to one hundred years of scientific inertia, politics, and greed propagated by an unwitting confederacy of dunces, it’s still not an established treatment for cancer. In all probability Coley’s vaccine never will be because you can’t patent a century-old drug.

Many discoveries of the first rank are for a time ignored or ridiculed. (Conversely, many discoveries, like radiation therapy, are for a time overrated.) What happened to the discovery of William Coley, who died largely forgotten and broke, having lost his money in the stock market crash of 1929, was, sadly, nothing new. What was new, though Coley didn’t know it at the time, was that he made the first scientific association between the immune system and saccharides, the sugars that heal.

As an early indication of saccharides’ worth, Coley’s toxins are just the tip of the iceberg. In the past twenty years, the amount of information garnered about these sugars has increased dramatically. Of the more than two hundred sugars, eight are essential to optimal body functioning. Far more than just a ready source of fuel for the cells, these eight essential sugars have potent antiviral, antibacterial, antiparasitic, and of course antitumor effects.23

Essential saccharides have also been shown in clinical trials to reduce allergies and to allay symptoms in such chronic diseases as arthritis, diabetes, lupus, and kidney disease. They accel- erate the healing of burns and wounds and help heal skin conditions—from poison ivy to psoriasis. They increase the body’s resistance to viruses, including those that cause the common cold, influenza, herpes, and hepatitis. They quell the recurrent bacterial ear infections that plague toddlers and children. Some people with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War syndrome, and HIV have reported improvement in their symptoms when they supplement their diet with these simple sugars.

The Eight Essential Saccharides

When most of us think of sugar, we think only of table sugar from sugarcane, which consists of two saccharides, glucose and fructose. The eight essential saccharides our bodies need are mannose, glucose, galactose, xylose, fucose (not to be confused with fructose), N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, and N-acetylneuraminic acid. These eight essential saccharides compose the main focus of Sugars That Heal. Only two of these essential sugars, glucose (found in plants and table sugar) and galactose (found in milk products and certain pectins), are common in our diets. Although fructose, found in fruits and table sugar, is also a part of most diets, it’s not an essential saccharide.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Dr. Mondoa makes an important contribution to the discovery of how Nature aids in the healing process. "Sugars That Heal" offers revolutionary new health information based on the science of glyconutrients--foods and supplements that contain saccharides.