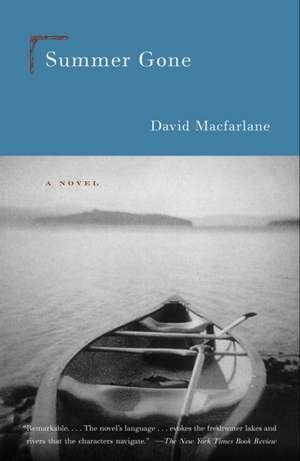

Summer Gone

Autor David MacFarlane Editat de Jenny Mintonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2001

When Bay Newby is twelve he is sent north for the first time, and he falls in love with the life of ritual, beauty, and stark privilege of summer camp. Then the death of his baby sister calls him home, and it will be twenty-three years before his next “perfect summer.” The summer he spends with his young son will contain loss also, but also discovery and redemption. Summer Gone is a novel of layered experience, of life, death and love as seen through the eyes of a young boy as he grows into a wiser–and more haunted–man.

Preț: 74.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 112

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.29€ • 14.76$ • 11.89£

14.29€ • 14.76$ • 11.89£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385720755

ISBN-10: 0385720750

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385720750

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

David Macfarlane is a columnist for The Globe and Mail. He lives in Toronto, Canada.

Extras

When Dr. Alistair Laird fell suddenly ill early one spring, not long after his seventy-first birthday, his wishes were that no ceremony attend his death. He was a handsome, crag-faced man. He was known as Laird to everyone, including his wife, Nora, and his three stepdaughters, Julia, Pru, and Sarah. He was kindly, in his way. He was also bombastic, in his way. And for someone who was dying, and dying rather quickly, Laird made his exit plans known with some force.

"Perhaps," said the hospital chaplain, who ventured once and only once into Laird's room, "a memorial service, a gathering of family and friends . . ."

Laird moved his dry lips.

"I beg your pardon." The chaplain leaned forward.

A gasp of stale breath. "Get out."

It was Bay who witnessed this. During those unsettled and sad days, it was Bay who was often there, in the hospital room.

Of course, it was Laird's wife who bore the brunt. Nora, whose round, open face had taken on a strained expression no one had seen before. Nora, who always wore the perfume Laird liked, and who always had a kind word for the nurses, and whose substantial weight was beginning to bear down on her tired legs, as she paced the corridor in her comfortable old cardigan when the doctors came into Laird's room. It was Nora, of course, who was in the hospital for long bedside shifts, but when, finally, she was exhausted, when finally she went home, to a bath, to some food, to the blankness of the sleeping pills she was using for the first and only time in her life, she wanted someone to be there. Julia and Pru, and their husbands and young families, lived far from downtown. It was the busiest time of the publishing year for Sarah ? three children's novels, two nursery rhyme anthologies, and the usual raft of Learning to Read paperbacks were coming out of Children's Press. And so it was Bay who was sitting in the hospital room, across from the end of Laird's bed, beside the window, when Laird made his wishes so clear to the chaplain.

Bay was a little taken aback ? not nearly as taken aback as the chaplain ? but not particularly surprised. The views that Laird held on the subject of religion and its attendant ceremony were well known to his family and his friends. And his views on these matters ? and on the subject of funerals ? had not softened in the least now that he was face to face with the green walls, plasma drips, fish sticks, and plastic pill tumblers of his own mortality.

"Nothing," Laird had said. "I'd like. Nothing."

This was when the subject first came up. Or rather, when it came up for the first unwhispered time. For although Laird, by then, had known for a week what was quickly to come, his family had been floundering from doctor to doctor, hope to hope. As families will.

The family meeting took place in Laird's hospital room. Sarah was sitting at the foot of the narrow bed. Her mother was in a chair at the head. She was holding Laird's hand. Sarah's two younger sisters, and their husbands, were standing by the large, unadorned window. Bay was at the closed door.

Beside Laird's bed were piled a few of the history books he had always enjoyed reading. They were now too heavy for him to hold. Beside the books was the Walkman the family had bought for him in the hospital, and which he said he hated. Tapes of his favourite Schubert, his favourite Beethoven sat there, ignored. "Music," he had said, "must echo around things.To be alive. Can't be injected."

Laird's feet were pale. He complained of how cold they were. Sarah was massaging them. She said, "We can't do . . . nothing."

There was a faint echo of Laird's old, gruff growl. It was a very characteristic growl. The growl his family had heard so often when they were growing up ? when they came back from school to report that they were memorizing Psalm 23 for an assembly, or that their teacher liked to start the day with the Lord's Prayer. From his pillows, Laird looked at Sarah fiercely. "Why not?" he asked. "Why not do nothing?" His eyes gleamed for a second with the old fire of the debates he had so often waged at the dinner table. "'Nothing' seems fitting. Under the circumstances."

"Well," she said. "There's Mom."

Nora's eyes were wide and attentive. Her fine skin, her abundant white hair, her long, pretty lashes, her unbearable concern were all poised there. She was on the edge of something. She was unable to speak.

Laird said, "Nora is a big girl." He gave a feeble pat to the back of his wife's hand.

"And there's your friends. And there's us . . ."

"Look." Laird wheezed. He coughed. "I'm the one. Who's bloody well dying."

It was the first time the word had been spoken openly. So matter-of-factly. It hung there, amid the leafy cloy of the delivered flowers, the odour of untouched dinner, the scent of moisturizer cream and soap and disinfectant, the dim smell of bedsheets.

"So what I want," Laird said. "Is. After the cremation. Throw out my ashes. With the garbage."

He had forbidden a funeral, forbidden a memorial service, forbidden his family the expense of anything beyond the most rudimentary disposal. He was a doctor. A stubborn pragmatist. A faithful atheist. A Scot.

Laird frowned. He said, "And I mean. Regular pickup. No goddamn recycling."

"Perhaps," said the hospital chaplain, who ventured once and only once into Laird's room, "a memorial service, a gathering of family and friends . . ."

Laird moved his dry lips.

"I beg your pardon." The chaplain leaned forward.

A gasp of stale breath. "Get out."

It was Bay who witnessed this. During those unsettled and sad days, it was Bay who was often there, in the hospital room.

Of course, it was Laird's wife who bore the brunt. Nora, whose round, open face had taken on a strained expression no one had seen before. Nora, who always wore the perfume Laird liked, and who always had a kind word for the nurses, and whose substantial weight was beginning to bear down on her tired legs, as she paced the corridor in her comfortable old cardigan when the doctors came into Laird's room. It was Nora, of course, who was in the hospital for long bedside shifts, but when, finally, she was exhausted, when finally she went home, to a bath, to some food, to the blankness of the sleeping pills she was using for the first and only time in her life, she wanted someone to be there. Julia and Pru, and their husbands and young families, lived far from downtown. It was the busiest time of the publishing year for Sarah ? three children's novels, two nursery rhyme anthologies, and the usual raft of Learning to Read paperbacks were coming out of Children's Press. And so it was Bay who was sitting in the hospital room, across from the end of Laird's bed, beside the window, when Laird made his wishes so clear to the chaplain.

Bay was a little taken aback ? not nearly as taken aback as the chaplain ? but not particularly surprised. The views that Laird held on the subject of religion and its attendant ceremony were well known to his family and his friends. And his views on these matters ? and on the subject of funerals ? had not softened in the least now that he was face to face with the green walls, plasma drips, fish sticks, and plastic pill tumblers of his own mortality.

"Nothing," Laird had said. "I'd like. Nothing."

This was when the subject first came up. Or rather, when it came up for the first unwhispered time. For although Laird, by then, had known for a week what was quickly to come, his family had been floundering from doctor to doctor, hope to hope. As families will.

The family meeting took place in Laird's hospital room. Sarah was sitting at the foot of the narrow bed. Her mother was in a chair at the head. She was holding Laird's hand. Sarah's two younger sisters, and their husbands, were standing by the large, unadorned window. Bay was at the closed door.

Beside Laird's bed were piled a few of the history books he had always enjoyed reading. They were now too heavy for him to hold. Beside the books was the Walkman the family had bought for him in the hospital, and which he said he hated. Tapes of his favourite Schubert, his favourite Beethoven sat there, ignored. "Music," he had said, "must echo around things.To be alive. Can't be injected."

Laird's feet were pale. He complained of how cold they were. Sarah was massaging them. She said, "We can't do . . . nothing."

There was a faint echo of Laird's old, gruff growl. It was a very characteristic growl. The growl his family had heard so often when they were growing up ? when they came back from school to report that they were memorizing Psalm 23 for an assembly, or that their teacher liked to start the day with the Lord's Prayer. From his pillows, Laird looked at Sarah fiercely. "Why not?" he asked. "Why not do nothing?" His eyes gleamed for a second with the old fire of the debates he had so often waged at the dinner table. "'Nothing' seems fitting. Under the circumstances."

"Well," she said. "There's Mom."

Nora's eyes were wide and attentive. Her fine skin, her abundant white hair, her long, pretty lashes, her unbearable concern were all poised there. She was on the edge of something. She was unable to speak.

Laird said, "Nora is a big girl." He gave a feeble pat to the back of his wife's hand.

"And there's your friends. And there's us . . ."

"Look." Laird wheezed. He coughed. "I'm the one. Who's bloody well dying."

It was the first time the word had been spoken openly. So matter-of-factly. It hung there, amid the leafy cloy of the delivered flowers, the odour of untouched dinner, the scent of moisturizer cream and soap and disinfectant, the dim smell of bedsheets.

"So what I want," Laird said. "Is. After the cremation. Throw out my ashes. With the garbage."

He had forbidden a funeral, forbidden a memorial service, forbidden his family the expense of anything beyond the most rudimentary disposal. He was a doctor. A stubborn pragmatist. A faithful atheist. A Scot.

Laird frowned. He said, "And I mean. Regular pickup. No goddamn recycling."

Recenzii

“Remarkable.... The novel’s language...evokes the freshwater lakes and rivers that the characters navigate.”

--The New York Times Book Review

“A remarkable achievement full of wit, intelligence, and humane charm.”

--Toronto Star

“Spellbinding.... Macfarlane’s luminous prose is itself like summer: it shimmers.”

--Publishers Weekly

--The New York Times Book Review

“A remarkable achievement full of wit, intelligence, and humane charm.”

--Toronto Star

“Spellbinding.... Macfarlane’s luminous prose is itself like summer: it shimmers.”

--Publishers Weekly

Descriere

Set among the islands and lakes of "cottage country", this beautifully crafted novel from one of Canada's premier writers is a layered experience of life, death, and love as seen through the eyes of a young boy who grows into a wiser--and more haunted--man.