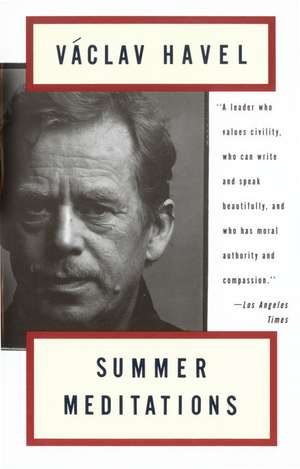

Summer Meditations

Autor Vaclav Havel Traducere de PAUL WILSONen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 1993

Havel, now president of the Czech Republic, addresses the legacy of Communism as the euphoria of the Velvet Revolution gives way to a more problematic reality. Yet even as he grapples with the challenges of political change, he affirms his belief in a politics motivated by moral responsibility; in an economy tempered by compassion; and in the central roles of art and culture in the transformation of society. Summer Meditations is not only a timely and necessary testament of events in Eastern Europe but a profound reflection upon the nature and practice of politics and a stirring call for morality, civility, and openness in public life throughout the world.

Preț: 90.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 135

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.27€ • 17.92$ • 14.43£

17.27€ • 17.92$ • 14.43£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679744979

ISBN-10: 0679744975

Pagini: 174

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0679744975

Pagini: 174

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Extras

Foreword

These meditations were inspired by conversations I had with Pavel Tigrid and Michael Žantovský, who prodded me into setting my thoughts down. To both of these men, I owe my thanks. I wrote the meditations at the end of July and the beginning of August 1991, and edited them at the end of August. Then, in late February of this year — in view of the momentous changes that had meanwhile taken place in the Soviet Union, and also in view of the resistance some of my proposals had met with in our Parliament — I reviewed some of the contents of this book especially for the English-language edition. Some of my comments have been integrated into the text.

I should say, however, that in fundamental things — in my concept of politics, in how I see its inner spirit — absolutely nothing has changed. I still see things and feel about things as I did when I wrote the final chapter of this book. Naturally, faced with the increasing complications of our public life at home, I have become aware of how immensely difficult it is to be guided in practice by the principles and ideals in which I believe. But I have not abandoned them in anyway.

Václav Havel

Prague, March 1992

Introduction

When the idea first came up that I should let my name stand for president of Czechoslovakia, it seemed like an absurd joke. All my life I had opposed the powers that be. I had never held political office, not even for a moment. I had always placed great store in my independence, and I had never like anything too serious, too ceremonial, too official. Suddenly, I was on the way to holding an official position and, moreover, the highest in the land.

Slightly less than a month after this shocking proposal was put to me, I was unanimously elected president of my country. It happened quickly and unexpectedly, almost overnight one could say, giving me little time to prepare myself and my thoughts for the job. (I remember that a few short hours before the great demonstration at which Jiří Bartoška, on behalf of Civic Forum and the Public Against Violence, declared my candidacy, I had not yet made up my mind to accept. I will refrain from naming the friends whose arguments finally persuaded me.)

It might be said that I was swept into office by the revolution.

When I think about it today with a cool head, and after the passage of time, I find myself somewhat surprised that I was so surprised. After all, when I get involved in something (in my usual all-out manner) I often find myself at the head of it before long — not because I am more clever or more ambitious than the rest, but because I seem to get along with people, to be able to reconcile and unite them, to act as a sort of unifying agent. So it was only part of the natural course of events that although I had no formal position in the Civic Forum I was perceived as the central figure, and when the Communist power structure crumbled so quickly, and even the president of the republic resigned at our request, I was asked to become a candidate for office.

Although I believe I have foresight in other matters, I displayed a lack of perspicacity where I myself was concerned.

Nevertheless, I did not hesitate for long, and not just because there was no time for hesitation, but also because I understood the task as an extension of what I had done before — that is, a natural continuation of my former civic involvement and my activities in the revolutionary events of 1989. It simply seemed to me that, since I had been saying A for so long, I could not refuse to say B; it would have been irresponsible of me to criticize the Communist regime all my life and then, when it finally collapsed (with some help from me), refuse to take part in the creation of something better.

My first term as president was brief, from December 29, 1989 to June 5, 1990. I understood that as a temporary period of service to our cause, and I didn't spend much time worrying about whether I was right for the job, or whether I enjoyed doing it; in the atmosphere of general enthusiasm over our new freedom, so quickly and elegantly won, I was simply "pulled forward by Being". With no embarrassment, no stage fright, no hesitation, I did everything I had to do. I was capable of speaking extempore (I who ahd never before spoken in public!) to several packed public squares a day, of negotiating confidently with the heads of great powers, of addressing foreign parliaments, and so on. In short, I was able to behave as masterfully as if I had been prepared and schooled for the presidency all my life. This was not because historical opportunity suddenly uncovered in me some special aptitude for the office, but because I became "an instrument of the time". That special time caught me up in its wild vortex — in the absence of leisure to reflect on the matter — compelled me to do what had to be done. My wife had the same experience: I was pleasantly surprised at the matter-of-factness with which she, who had persistently opposed my standing for the office, accepted her new position and all the duties that went with it. She found her own public identity and work, and did not let it affect her in any adverse way. Others in my position would have done the same thing, though perhaps in different ways. There was no choice. History — if I may put it this way — forged ahead and through me, guiding my activities.

My second election was also preceded by a few hesitations. I was the only candidate. I was nominated by the forces that had clearly won the elections, and the opposition did not oppose them in this manner. I made no personal effort to be elected, nor did I do anything to prevent it. Had I refused to run a second time I would have been generally perceived as abandoning the battlefield, if not actually forsaking a job undertaken. Thus my second term in office was again, in a sense, a mere extension of the first, its logical continuation, a fulfilment of the task I had already assumed: to help this country move from totalitarianism to democracy, from satellitehood to independence, from a centrally directed economy to market economics.

Today the situation is radically different. The era of enthusiasm, unity, mutual understanding, and dedication to a common cause is over. For a long time now I have no longer felt like a bemused plaything of history who is drawn in the same direction as others are, who believes that all are working to the same end as he is, and that they therefore understand him and he need not think too carefully about himself and his program, since "everything is clear". Times have changed, clouds have filled the sky, clarity and general harmony have disappeared, and our country is heading into a period of not inconsiderable difficulties.

The time of hard, everyday work has come, a time in which conflcting interests have surfaced, a time for sobering up, a time when all of us — and especially those in politics — must make it very clear what we stand for.

I too suddenly feel I owe something to my fellow-citizens: a clear, concise account of where I stand, what I actually want, and what I think. True, I have already given hundreds of speeches. Every week I talk to the public on the air. But precisely because my speeches have appeared in so many places (and who, in the rush of events has had time to follow and take account of them all?), it still seems necessary to me to gather my thoughts, opinions, and intentions together in a single coherent whole.

This book is not a collection of essays, or even less a work of political science. It is merely a series of spontaneously written comments on how I see this country and its problems today, how I see its future, and what I wish to put my efforts behind.

These meditations were inspired by conversations I had with Pavel Tigrid and Michael Žantovský, who prodded me into setting my thoughts down. To both of these men, I owe my thanks. I wrote the meditations at the end of July and the beginning of August 1991, and edited them at the end of August. Then, in late February of this year — in view of the momentous changes that had meanwhile taken place in the Soviet Union, and also in view of the resistance some of my proposals had met with in our Parliament — I reviewed some of the contents of this book especially for the English-language edition. Some of my comments have been integrated into the text.

I should say, however, that in fundamental things — in my concept of politics, in how I see its inner spirit — absolutely nothing has changed. I still see things and feel about things as I did when I wrote the final chapter of this book. Naturally, faced with the increasing complications of our public life at home, I have become aware of how immensely difficult it is to be guided in practice by the principles and ideals in which I believe. But I have not abandoned them in anyway.

Václav Havel

Prague, March 1992

Introduction

When the idea first came up that I should let my name stand for president of Czechoslovakia, it seemed like an absurd joke. All my life I had opposed the powers that be. I had never held political office, not even for a moment. I had always placed great store in my independence, and I had never like anything too serious, too ceremonial, too official. Suddenly, I was on the way to holding an official position and, moreover, the highest in the land.

Slightly less than a month after this shocking proposal was put to me, I was unanimously elected president of my country. It happened quickly and unexpectedly, almost overnight one could say, giving me little time to prepare myself and my thoughts for the job. (I remember that a few short hours before the great demonstration at which Jiří Bartoška, on behalf of Civic Forum and the Public Against Violence, declared my candidacy, I had not yet made up my mind to accept. I will refrain from naming the friends whose arguments finally persuaded me.)

It might be said that I was swept into office by the revolution.

When I think about it today with a cool head, and after the passage of time, I find myself somewhat surprised that I was so surprised. After all, when I get involved in something (in my usual all-out manner) I often find myself at the head of it before long — not because I am more clever or more ambitious than the rest, but because I seem to get along with people, to be able to reconcile and unite them, to act as a sort of unifying agent. So it was only part of the natural course of events that although I had no formal position in the Civic Forum I was perceived as the central figure, and when the Communist power structure crumbled so quickly, and even the president of the republic resigned at our request, I was asked to become a candidate for office.

Although I believe I have foresight in other matters, I displayed a lack of perspicacity where I myself was concerned.

Nevertheless, I did not hesitate for long, and not just because there was no time for hesitation, but also because I understood the task as an extension of what I had done before — that is, a natural continuation of my former civic involvement and my activities in the revolutionary events of 1989. It simply seemed to me that, since I had been saying A for so long, I could not refuse to say B; it would have been irresponsible of me to criticize the Communist regime all my life and then, when it finally collapsed (with some help from me), refuse to take part in the creation of something better.

My first term as president was brief, from December 29, 1989 to June 5, 1990. I understood that as a temporary period of service to our cause, and I didn't spend much time worrying about whether I was right for the job, or whether I enjoyed doing it; in the atmosphere of general enthusiasm over our new freedom, so quickly and elegantly won, I was simply "pulled forward by Being". With no embarrassment, no stage fright, no hesitation, I did everything I had to do. I was capable of speaking extempore (I who ahd never before spoken in public!) to several packed public squares a day, of negotiating confidently with the heads of great powers, of addressing foreign parliaments, and so on. In short, I was able to behave as masterfully as if I had been prepared and schooled for the presidency all my life. This was not because historical opportunity suddenly uncovered in me some special aptitude for the office, but because I became "an instrument of the time". That special time caught me up in its wild vortex — in the absence of leisure to reflect on the matter — compelled me to do what had to be done. My wife had the same experience: I was pleasantly surprised at the matter-of-factness with which she, who had persistently opposed my standing for the office, accepted her new position and all the duties that went with it. She found her own public identity and work, and did not let it affect her in any adverse way. Others in my position would have done the same thing, though perhaps in different ways. There was no choice. History — if I may put it this way — forged ahead and through me, guiding my activities.

My second election was also preceded by a few hesitations. I was the only candidate. I was nominated by the forces that had clearly won the elections, and the opposition did not oppose them in this manner. I made no personal effort to be elected, nor did I do anything to prevent it. Had I refused to run a second time I would have been generally perceived as abandoning the battlefield, if not actually forsaking a job undertaken. Thus my second term in office was again, in a sense, a mere extension of the first, its logical continuation, a fulfilment of the task I had already assumed: to help this country move from totalitarianism to democracy, from satellitehood to independence, from a centrally directed economy to market economics.

Today the situation is radically different. The era of enthusiasm, unity, mutual understanding, and dedication to a common cause is over. For a long time now I have no longer felt like a bemused plaything of history who is drawn in the same direction as others are, who believes that all are working to the same end as he is, and that they therefore understand him and he need not think too carefully about himself and his program, since "everything is clear". Times have changed, clouds have filled the sky, clarity and general harmony have disappeared, and our country is heading into a period of not inconsiderable difficulties.

The time of hard, everyday work has come, a time in which conflcting interests have surfaced, a time for sobering up, a time when all of us — and especially those in politics — must make it very clear what we stand for.

I too suddenly feel I owe something to my fellow-citizens: a clear, concise account of where I stand, what I actually want, and what I think. True, I have already given hundreds of speeches. Every week I talk to the public on the air. But precisely because my speeches have appeared in so many places (and who, in the rush of events has had time to follow and take account of them all?), it still seems necessary to me to gather my thoughts, opinions, and intentions together in a single coherent whole.

This book is not a collection of essays, or even less a work of political science. It is merely a series of spontaneously written comments on how I see this country and its problems today, how I see its future, and what I wish to put my efforts behind.

Recenzii

"It is surely for the president of a modern country, while still in office, to offer the public so unsparing an expose of his political and personal philosophy. And what is even more striking still is the elevated quality, morally and intellectually, of the philosophy that emerges from this effort."

-- George F. Kennan, The New York Review of Books

"An eloquent reminder that moral struggles do not end with the overthrow of dictators." -- Christian Science Monitor

Translated from the Czech by Paul Wilson

-- George F. Kennan, The New York Review of Books

"An eloquent reminder that moral struggles do not end with the overthrow of dictators." -- Christian Science Monitor

Translated from the Czech by Paul Wilson

Descriere

In a work written while he was president of Czechoslovakia, Havel offers profound reflections upon the nature and practice of politics throughout the world, and extends a stirring call for a moral political system, a responsible free market, and a statecraft that honors human needs.