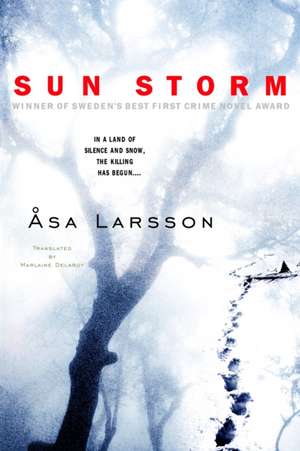

Sun Storm

Autor Asa Larsson Traducere de Marlaine Delargyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2006

Rebecka Martinsson is heading home to Kiruna, the town she’d left in disgrace years before. A Stockholm attorney, Rebecka has a good reason to return: her friend Sanna, whose brother has been horrifically murdered in the revivalist church his charisma helped create. Beautiful and fragile, Sanna needs someone like Rebecka to remove the shadow of guilt that is engulfing her, to forestall an ambitious prosecutor and a dogged policewoman. But to help her friend, and to find the real killer of a man she once adored and is now not sure she ever knew, Rebecka must relive the darkness she left behind in Kiruna, delve into a sordid conspiracy of deceit, and confront a killer whose motives are dark, wrenching, and impossible to guess....

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 94.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.15€ • 18.88$ • 14.99£

18.15€ • 18.88$ • 14.99£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385340786

ISBN-10: 0385340788

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 155 x 230 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0385340788

Pagini: 310

Dimensiuni: 155 x 230 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: DELTA

Notă biografică

Åsa Larsson was born in Kiruna, Sweden, in 1966. She studied in Uppsala and lived for some years in Stockholm but now prefers the rural life with her husband, two children, and several chickens. A former tax lawyer, she now writes full-time and is the author of Sun Storm, winner of Sweden’s Best First Crime Novel Award, and The Black Path, which Delacorte will publish in 2007.

Extras

And evening came and morning came, the first day

When Viktor Strandgård dies it is not, in fact, for the first time. He lies on his back in the church called The Source of All Our Strength and looks up through the enormous windows in its roof. It’s as if there is nothing between him and the dark winter sky up above.

You can’t get any closer than this, he thinks. When you come to the church on the mountain at the end of the world, the sky will be so close that you can reach out and touch it.

The Aurora Borealis twists and turns like a dragon in the night sky. Stars and planets are compelled to give way to her, this great miracle of shimmering light, as she makes her unhurried way across the vault of heaven.

Viktor Strandgård follows her progress with his eyes.

I wonder if she sings? he thinks. Like a lonely whale beneath the sea?

And as if his thoughts have touched her, she stops for a second. Breaks her endless journey. Contemplates Viktor Strandgård with her cold winter eyes. Because he is as beautiful as an icon lying there, to tell the truth, with the dark blood like a halo round his long, fair, St. Lucia hair. He can’t feel his legs anymore. He is getting drowsy. There is no pain.

Curiously enough it is his previous death he is thinking of as he lies there looking into the eye of the dragon. That time in the late winter when he came cycling down the long bank toward the crossroads at Adolf Hedinsvägen and Hjalmar Lundbohmsvägen. Happy and redeemed, his guitar on his back. He remembers how the wheels of his bicycle skidded helplessly on the ice as he tried desperately to brake. How he saw the woman in the red Fiat Uno coming from the right. How they stared at each other, the realization in the other’s eyes; now it’s happening, the icy slide toward death.

With that picture in his mind’s eye Viktor Strandgård dies for the second time in his life. Footsteps approach, but he doesn’t hear them. His eyes do not have to see the gleam of the knife once again. His body lies like an empty shell on the floor of the church; it is stabbed over and over again. And the dragon resumes her journey across the heavens, unmoved.

Monday, February 17

Rebecka Martinsson was woken by her own sharp intake of breath as fear stabbed through her body. She opened her eyes to darkness. Just between the dream and the waking, she had the strong feeling that there was someone in the flat. She lay still and listened, but all she could hear was the sound of her own heart thumping in her chest like a frightened hare. Her fingers fumbled for the alarm clock on the bedside table and found the little button to light up the face. Quarter to four. She had gone to bed four hours ago and this was the second time she had woken up.

It’s the job, she thought. I work too hard. That’s why my thoughts go round and round at night, like a hamster on a squeaking wheel.

Her head and the back of her neck were aching. She must have been grinding her teeth in her sleep. Might as well get up. She wound the duvet around her and went into the kitchen. Her feet knew the way without her needing to switch on the light. She put on the coffee machine and the radio. Bellman’s music played over and over as the water ran through the filter and Rebecka showered.

Her long hair could dry in its own time. She drank her coffee while she was getting dressed. Over the weekend she had ironed her clothes for the week and hung them up in the wardrobe. Now it was Monday. On Monday’s hanger was an ivory blouse and a navy blue Marella suit. She sniffed at the tights she’d been wearing the previous day; they’d do. They’d gone a bit wrinkly around the ankles, but if she stretched them and tucked them under her feet it wouldn’t show. She’d just have to make sure she didn’t kick her shoes off during the day. It didn’t bother her; it was only worth spending time worrying about your underwear and your tights if you thought somebody was going to be watching you get undressed. Her underwear had seen better days and was turning gray.

An hour later she was sitting at her computer in the office. The words flowed through her mind like a clear mountain stream, down her arms and out through her fingers, flying over the keyboard. Work soothed her mind. It was as if the morning’s unpleasantness had been blown away.

It’s strange, she thought. I moan and complain like all the other young lawyers about how unhappy the job makes me. But I feel a sense of peace when I’m working. Happiness, almost. It’s when I’m not working I feel uneasy.

The light from the street below forced its way with difficulty through the tall barred windows. You could still make out the sound of individual cars among the noise below, but soon the street would become a single dull roar of traffic. Rebecka leaned back in her chair and clicked on “print.” Out in the dark corridor the printer woke up and got on with the first task of the day. Then the door into reception banged. She sighed and looked at the clock. Ten to six. That was the end of her peace and quiet.

She couldn’t hear who had come in. The thick carpets in the corridor deadened the sound of footsteps, but after a while the door of her room opened.

“Am I disturbing you?” It was Maria Taube. She pushed the door open with her hip, balancing a mug of coffee in each hand. Rebecka’s copy was jammed under her right arm.

Both women were newly qualified lawyers with special responsibility for tax laws, working for Meijer & Ditzinger. The office was at the very top of a beautiful turn-of-the-century building on Birger Jarlsgatan. Semi-antique Persian carpets ran the length of the corridors, and here and there stood imposing sofas and armchairs in attractively worn leather. Everything exuded an air of experience, influence, money and competence. It was an office that filled clients with an appropriate mixture of security and reverence.

“By the time you die you must be so tired you hope there won’t be any sort of afterlife,” said Maria, and put a mug of coffee on Rebecka’s desk. “But of course that won’t apply to you, Maggie Thatcher. What time did you get here this morning? Or haven’t you been home at all?”

They’d both worked in the office on Sunday evening. Maria had gone home first.

“I’ve only just got here,” lied Rebecka, and took her copy out of Maria’s hand.

Maria sank down into the armchair provided for visitors, kicked off her ridiculously expensive leather shoes and drew her legs up under her body.

“Terrible weather,” she said.

Rebecka looked out the window with surprise. Icy rain was hammering against the glass. She hadn’t noticed earlier. She couldn’t remember if it had been raining when she came into work. In fact, she couldn’t actually remember whether she’d walked or taken the Underground. She gazed in a trance at the rain pouring down the glass as it beat an icy tattoo.

Winter in Stockholm, she thought. It’s hardly surprising that you shut down your brain when you’re outside. It’s different up at home, the blue shining midwinter twilight, the snow crunching under your feet. Or the early spring, when you’ve skied along the river from Grandmother’s house in Kurravaara to the cabin in Jiekajärvi, and you sit down and rest on the first patch of clear ground where the snow has melted under a pine tree. The tree bark glows like red copper in the sun. The snow sighs with exhaustion, collapsing in the warmth. Coffee, an orange, sandwiches in your rucksack.

The sound of Maria’s voice drew her back. Her thoughts scrabbled and tried to escape, but she pulled herself together and met her colleague’s raised eyebrows.

“Hello! I asked if you were going to listen to the news.”

“Yes, of course.”

Rebecka leaned back in her chair and stretched out her arm to the radio on the windowsill.

Lord, she’s thin, thought Maria, looking at her colleague’s rib cage as it protruded from under her jacket. You could play a tune on those ribs.

Rebecka turned the radio up and both women sat with their coffee cups cradled between their hands, heads bowed as if in prayer.

Maria blinked. It felt as if something were scratching her tired eyes. Today she had to finish the appeal for the county court in the Stenman case. Måns would kill her if she asked him for more time. She felt a burning pain in her midriff. No more coffee before lunch. You sat here like a princess in a tower, day and night, evenings and weekends, in this oh-so-charming office with all its bloody traditions which could go to hell, and all the pissed-up partners looking straight through your blouse while outside, life just carried on without you. You didn’t know whether you wanted to cry or start a revolution but all you could actually manage was to drag yourself home to the TV and pass out in front of its soothing, flickering screen.

It’s six o’clock and here are the morning headlines. A well-known religious leader around the age of thirty was found murdered early this morning in the church of The Source of All Our Strength in Kiruna. The police in Kiruna are not prepared to make a statement about the murder at this stage, but during the morning they have revealed that no one has been detained so far, and the murder weapon has not yet been found. . . . A new study shows that more and more communities are ignoring their obligations, according to Social Services. . . .

Rebecka swung her chair round so quickly that she banged her hand on the windowsill. She turned the radio off with a crash and at the same time managed to spill coffee on her knee.

“Viktor,” she exclaimed. “It has to be him.”

Maria looked at her with surprise.

“Viktor Strandgård? The Paradise Boy? Did you know him?”

Rebecka avoided Maria’s gaze. Ended up staring at the coffee stain on her skirt, her expression closed and blank. Thin lips, pressed together.

“Of course I knew of him. But I haven’t been home to Kiruna for years. I don’t know anybody up there anymore.”

Maria got up from the armchair, went over to Rebecka and pried the coffee cup from her colleague’s stiff hands.

“If you say you didn’t know him, that’s fine by me, but you’re going to faint in about thirty seconds. You’re as white as a sheet. Bend over and put your head between your knees.”

Like a child Rebecka did as she was told. Maria went to the bathroom and fetched paper towels to try to save Rebecka’s suit from the coffee stain. When she came back Rebecka was leaning back in her chair.

“Are you okay?” asked Maria.

“Yes,” answered Rebecka absently, and looked on helplessly as Maria started to dab at her skirt with a damp towel. “I did know him,” she said.

“Well, I didn’t exactly need a lie detector,” said Maria without looking up. “Are you upset?”

“Upset? I don’t know. Frightened, maybe.”

Maria stopped her frantic dabbing.

“Frightened of what?”

“I don’t know. That somebody will—”

The telephone burst in with its shrill signal before Rebecka could finish. She jumped and stared at it, but didn’t pick it up. After the third ring Maria answered. She put her hand over the receiver so that the person on the other end couldn’t hear her, and whispered:

“It’s for you and it must be from Kiruna, because there’s a Moomin troll on the other end.”

When Inspector Anna-Maria Mella’s telephone rang, she was already awake. The winter moon filled the room with its chilly white light. The birch trees outside the window drew blue shadow pictures on the walls with their bent and aching limbs. As soon as the phone started to ring, she picked it up.

“It’s Sven-Erik—were you awake?”

“Yes, but I’m in bed. What is it?”

She heard Robert sigh and glanced in his direction. Had he woken up? No, his breathing became deep and regular again. Good.

“Suspected murder in The Source of All Our Strength church,” said Sven-Erik.

“So? I’m on desk duty since Friday, in case you’ve forgotten.”

“I know” Sven-Erik’s voice sounded troubled—“but bloody hell, Anna-Maria, this is something else. You could just come and have a look. The forensic team will be finished soon, and we can go in. I’ve got Viktor Strandgård lying here, and it looks like a slaughterhouse. I’d guess we’ve got about an hour before every bloody TV station is here with cameras and the whole circus.”

“I’ll be there in twenty minutes.”

There’s a turn-up, she thought. Sven-Erik ringing to ask me for help. He’s changed.

Sven-Erik didn’t answer, but Anna-Maria heard his suppressed sigh of relief just before he put the phone down.

She turned to Robert and gazed at his sleeping face. His cheek was resting on the back of his hand and his red lips were parted slightly. She found it irresistibly sexy that a few strands of gray had started to appear in his straggling moustache and at his temples. Robert himself used to stand in front of the bathroom mirror looking anxiously at his receding hairline.

“The desert is spreading,” he would say ruefully.

She kissed him on the mouth. Her stomach got in the way, but she managed it. Twice.

“I love you,” he assured her, still asleep. His hand fumbled under the sheet to draw her close, but by then she had already managed to sit upright on the edge of the bed. All of a sudden she was desperate for a pee. Her bladder was bursting all the time. She’d already been to the bathroom twice during the night.

Quarter of an hour later Anna-Maria climbed out of her Ford Escort in the car park below The Source of All Our Strength church. It was still bitterly cold. The air pinched and nipped at her cheeks. If she breathed through her mouth her throat and lungs hurt. If she breathed through her nose the fine hairs in her nostrils froze when she inhaled. She wound her scarf around to cover her mouth and looked at her watch. Half an hour max; any longer and the car wouldn’t start. It was a big parking lot with spaces for at least four hundred cars. Her light-red Escort looked small and insignificant beside Sven-Erik Stålnacke’s Volvo 740. A radio car was parked next to Sven-Erik’s Volvo. Apart from that there were only a dozen or so cars, completely covered in snow. The forensic team must have gone already. She started to walk up the narrow path to the church on Sandstensberget. The frost lay like icing on the birch trees, and right at the top of the hill the mighty Crystal Church soared up into the night sky, surrounded by stars and planets. It stood there like a gigantic illuminated ice cube, shimmering with the Aurora Borealis.

All bloody show, she thought as she struggled up the bank. This lot are rolling in money; they ought to be giving some of their cash to Save the Children instead. But I suppose it’s more fun to sing gospel songs in a huge church than to dig wells in Africa.

In the distance she could see her colleagues Sven-Erik Stålnacke, Sergeant Tommy Rantakyrö and Inspector Fred Olsson outside the church door. Sven-Erik, bareheaded as usual, was standing quite still, leaning slightly backwards with his hands deep in the warm pockets of his fleece. The two younger men were bounding about like excited puppies. She couldn’t hear them, but she could see Rantakyrö’s and Olsson’s eager chatter coming out of their mouths like white bubbles. The puppies barked happily in greeting as soon as they caught sight of her.

“Hi,” yapped Tommy Rantakyrö, “how’s it going?”

“Fine,” she called back cheerfully.

“Soon we’ll be saying hello to your stomach first, then you’ll turn up quarter of an hour later,” said Fred Olsson.

Anna-Maria laughed.

She met Sven-Erik’s serious gaze. Small icicles had formed in his walrus moustache.

“Thanks for coming,” he said. “I hope you’ve had breakfast, because what’s in there won’t exactly give you an appetite. Shall we go in?”

“Do you want us to wait for you?”

Fred Olsson was stamping his feet up and down in the snow. He was looking from Sven-Erik to Anna-Maria and back again. Sven-Erik was supposed to be taking over during Anna-Maria’s leave, so technically he was in charge now. But since Anna-Maria was here as well it was a bit difficult to know who was making the decisions.

Anna-Maria kept quiet and looked at Sven-Erik. She was only there to keep him company.

“It would be good if you could hang on,” said Sven-Erik, “so we don’t suddenly get somebody coming along who has no business here before the body has been collected. But by all means come and stand inside the door if you’re cold.”

“Hell no, we can stand outside, I just wondered, that’s all,” Fred Olsson assured them.

“No problem.” Tommy Rantakyrö grinned with blue lips. “We’re men after all. Men don’t feel the cold.”

Sven-Erik went into the church right behind Anna-Maria and pulled the heavy door shut behind them. They walked slowly through the cloakroom, slumbering in the twilight. Long ranks of empty coat hangers rattled like an out-of-tune glockenspiel, set in motion by the draught as the cold air outside met the warmth inside. Two swing doors led into the main body of the church. Sven-Erik instinctively lowered his voice as they went in.

“It was Viktor Strandgård’s sister who rang the main office around three. She’d found him dead and she used the phone in the pastor’s office.”

“Where is she? At the station?”

“Well, no. We don’t know where she is. I left instructions to get somebody out there looking for her. There was nobody in the church when Tommy and Freddy got here.”

“What did the technicians say?”

“Look but don’t touch.”

The body was lying in the middle of the central aisle. Anna-Maria stopped a little way from it.

“Fucking hell,” she burst out.

“I did tell you,” said Sven-Erik, who was standing just behind her.

Anna-Maria pulled a little tape recorder from the inside pocket of her jacket. She hesitated for a moment. She usually spoke into it rather than making notes. But this wasn’t really her case. Maybe she ought to keep quiet and just sort of go along with Sven-Erik?

Don’t go making everything so complicated, she told herself, and switched on the tape recorder without even looking at her colleague.

“The time is five thirty-five,” she said into the microphone. “It’s the sixteenth, no seventeenth, of February. I’m standing in The Source of All Our Strength church and looking at someone who, as far as we know at the moment, is Viktor Strandgård, generally known as the Paradise Boy. The dead man is lying in the middle of the aisle. He appears to have been well and truly slit open, because he absolutely stinks and the carpet beneath the body is wet. This wetness is presumably blood, but it’s a little difficult to tell because he is lying on a red carpet. His clothes are also covered in blood and it isn’t possible to see very much of the wound in his stomach; it does seem, however, that some of his intestines are protruding, but the doctor can confirm that later. He’s wearing jeans and a jumper. The soles of his shoes are dry and the carpet under his shoes is not wet. His eyes have been gouged out. . . .”

Anna-Maria broke off and switched off the tape recorder. She moved round the body and bent over the face. She had been about to say that he made a beautiful corpse, but there were limits to what she could think aloud in front of Sven-Erik. The dead man’s face made her think of King Oedipus. She had seen the play on video at school. At the time she hadn’t been particularly affected by the scene where he put out his own eyes, but now the image came back to her with remarkable clarity. She needed to pee again. And she mustn’t forget about the car. Best get going. She switched on the tape recorder again.

“The eyes have been gouged out and the long hair is covered in blood. There must be a wound to the back of the head. There is a cut on the right of the neck, but no bleeding, and the hands are missing. . . .”

Anna-Maria turned inquiringly to Sven-Erik, who was pointing toward the rows of chairs. She bent down with difficulty and looked along the floor among the chairs.

“Oh, I see, one hand is lying three meters away under the chairs. But where’s the other?”

Sven-Erik shrugged.

“None of the chairs has been overturned,” she continued. “There are no indications of a struggle; what do you think, Sven-Erik?”

“No,” replied Sven-Erik, who disliked speaking into the tape recorder.

“Who took the photos?”

“Simon Larsson.”

Good, she thought. That meant they would have good pictures.

“Otherwise the church is tidy,” she went on. “This is the first time I’ve been in here. There are hundreds of frosted lamps along those sections of the walls that are not made of glass bricks. How high would it be? Must be more than ten meters. Huge windows in the roof. Blue chairs in rows, straight as a die. How many people would fit in here? Two thousand?”

“Plus the pulpit,” said Sven-Erik.

He wandered round and allowed his gaze to sweep over every surface like a vacuum cleaner.

Anna-Maria turned and looked at the pulpit towering behind her. The organ pipes soared upward and met their own reflection in the windows in the roof. It was an impressive sight.

“There isn’t really very much more to add,” said Anna-Maria hesitantly, as if some idea might work its way up from her subconscious and creep out through a gap in the syllables as she spoke. “There’s something . . . something that makes me feel frustrated when I look at all this. Besides the fact that this corpse is in the worst state I’ve ever seen—”

“Hey, you two! His lordship the assistant chief prosecutor is on his way up the hill.”

Tommy Rantakyrö had stuck his head in through the doorway.

“Who the hell rang him?” asked Sven-Erik, but Tommy had already disappeared.

Anna-Maria looked at him. Four years ago when she became team leader Sven-Erik had hardly spoken to her for the first six months. He had been deeply hurt because she had got the job he wanted. And now that he’d found his feet as her second in command, he didn’t want to take that extra step forward. She made a mental note to give him a pep talk later. But now he’d just have to manage by himself. Just as Assistant Chief Prosecutor Carl von Post stormed in through the door, she gave Sven-Erik an encouraging look.

“What the fuck is going on here?” yelled von Post.

He yanked off his fur hat and his hand went up to his mane of curly hair from sheer force of habit. He stamped his feet. The short walk up from the car park was enough to turn his feet to ice in his smart shoes from Church’s. He strode up to Anna-Maria and Sven-Erik but recoiled when he caught sight of the body on the floor.

“Oh, bloody hell,” he burst out, and looked anxiously down at his shoes to check whether he might have got them dirty.

“Why didn’t somebody ring me?” he went on, turning to Sven-Erik. “From now on I’m taking over the investigation, and you can expect a serious talk with the chief if you’ve been keeping me in the dark.”

“Nobody’s been keeping you in the dark, we didn’t know what had happened and we still don’t really know anything,” ventured Sven-Erik.

“Crap!” snapped the prosecutor. “And what the hell are you doing here?”

This was directed at Anna-Maria, who was standing in silence gazing at Viktor Strandgård’s mutilated arms.

“I rang her,” explained Sven-Erik.

“I see,” said von Post through clenched teeth. “So you rang her, but not me.”

Sven-Erik said nothing, and Carl von Post looked at Anna-Maria, who raised her eyes and met his gaze calmly.

Carl von Post clamped his teeth together so hard that his jaws ached. He’d always had a problem with this midget of a policewoman. She seemed to have her male colleagues on the Investigation squad by the balls, and he couldn’t work out why. And just look at her. One meter fifty at the most in her stocking feet, with a long horse’s face which more or less covered half her body. At the moment she was ready for a circus freak show with her enormous belly. Like a grotesque cube, she was as broad as she was tall. It just had to be the inevitable result of generations of inbreeding in those little isolated Lapp villages.

He waved his hand in the air as if to waft away his sharp words and started on a new tack.

“How are you feeling, Anna-Maria?” he asked, pasting on a gentle and sympathetic smile.

“Fine,” she answered without expression. “And you?”

“I reckon we’ll have the press round our ears in maybe an hour or so. It’ll be all hell let loose, so tell me what you know so far about the murder and the dead man; all I know is that he was a religious celebrity.”

Carl von Post sat down on one of the blue chairs and pulled off his gloves.

“I’ll let Sven-Erik tell you,” said Anna-Maria in a laconic but not unfriendly tone. “I’m supposed to be on desk duty until my time comes. I came along with Sven-Erik because he asked me to, and because two pairs of eyes see more than . . . well, you know all that. And now I need to pee. If you’ll excuse me.”

She noticed with satisfaction the pained smile on von Post’s face as she went off to the bathroom. To think that the word “pee” could offend his ears quite so much. She wouldn’t mind betting that his wife made sure she directed the stream of liquid onto the porcelain when she peed so his delicate little ears wouldn’t be troubled by the sound of piddling. Bloody man.

“Well,” said Sven-Erik when Anna-Maria had disappeared, “you can see things for yourself, and we don’t know much more. Somebody has killed him. And they’ve done it very thoroughly, I must say. The dead man is Viktor Strandgård, or the Paradise Boy as he’s known. He’s the main attraction in this huge church community. Nine years ago he was involved in a terrible car accident. He died at the hospital. His heart stopped and everything, but they got him back, and he could tell them all about what had happened during the operation and when they were trying to resuscitate him, that the doctor had dropped his glasses and so on. And then he said he’d been in heaven. He met angels, and Jesus. Anyway, one of the nurses who’d been involved in the operation was saved, and the woman who ran into him, and suddenly the whole of Kiruna was one big revivalist meeting. The three biggest free churches joined together to make one new church, The Source of All Our Strength. The congregation grew and in recent years they’ve built this church, started their own school and their own nursery, and held huge revivalist meetings. Tons of money is pouring in, and people come here from all over the world. Viktor Strandgård is—or was, I should say— employed by the church full-time, and he’s written a best seller. . . .”

“Himlen Tur och Retur, Heaven and Back.”

“That’s the one. He’s their golden calf, he’s been in all the papers, even Expressen and Aftonbladet, so there’s bound to be a lot written now. And the TV cameras will be up here.”

“Exactly,” said von Post, and stood up, looking impatient. “I don’t want anyone leaking information to the press. I’ll take over all contact with the media and I want you to report to me on a regular basis; anything that emerges during interrogation and so on, is that clear? Everything is to be passed on to me. When the journalists start asking questions you can say I’ll be holding a press conference on the steps of the church at twelve midday today. What’s your next move?”

“We need to get hold of the sister, she was the one who found the body; then we need to speak to the three pastors. The medical examiner is on his way from Luleå; he should be here any minute now.”

“Good. I want a report on the cause of death and a credible version of the course of events leading up to it at eleven-thirty, so be by the phone then. That’s all. If you’re done here I’ll just take a look around on my own for a bit.”

Oh, come on,” said Anna-Maria to Sven-Erik Stålnacke. “This has got to be better than sitting around interviewing pissed-up snowmobile riders.”

Her Ford Escort wouldn’t start, and Sven-Erik was giving her a lift home.

It was just as well, she thought; he needed encouragement so that he didn’t get fed up with the job.

“It’s that bastard von Pisspot,” Sven-Erik replied with a grimace. “As soon as I have anything to do with him I just feel like saying sod the lot of it, and just going through the motions every day until it’s time to go home.”

“Well, don’t think about him now. Think about Viktor Strandgård instead. The lunatic who killed him is out there somewhere, and you’re going to find him. Let that pompous old fool scream and shout and talk to the newspapers. The rest of us know who actually does all the work.”

“How can I not think about him? He’s watching me like a hawk all the time.”

“I know.”

She looked out through the car window. The houses still lay sleeping in the darkness of the streets, with just an occasional light in a window. The orange paper Advent stars were still hanging here and there. This year nobody had burned to death. There had been fights and the usual dose of misery, but no worse than usual. She felt slightly sick. Hardly surprising. She’d been up for a good hour and had eaten nothing. She realized she wasn’t concentrating on what Sven-Erik was saying, and rewound her memory to catch up. He’d asked how she’d managed to work with von Post.

“We never actually had that much to do with each other,” she said.

“Look, I could really do with your help, Anna-Maria. There’s going to be a hell of a lot of pressure on those of us working on this case, without that bully on top of everything else. I could do with a colleague’s support right now.”

“That sounds like blackmail to me.” Anna-Maria couldn’t help laughing.

“I’ll do whatever it takes. Blackmail, threats. In any case, it’s good for you to get a bit of exercise. You could at least be there and talk to the sister when we find her. Just help me get started.”

“Fine, ring me when you’ve found her.”

Sven-Erik bent forward over the steering wheel and looked up at the night sky.

“Just look at the moon,” he said with a smile. “I should be out there hunting foxes.”

From the Hardcover edition.

When Viktor Strandgård dies it is not, in fact, for the first time. He lies on his back in the church called The Source of All Our Strength and looks up through the enormous windows in its roof. It’s as if there is nothing between him and the dark winter sky up above.

You can’t get any closer than this, he thinks. When you come to the church on the mountain at the end of the world, the sky will be so close that you can reach out and touch it.

The Aurora Borealis twists and turns like a dragon in the night sky. Stars and planets are compelled to give way to her, this great miracle of shimmering light, as she makes her unhurried way across the vault of heaven.

Viktor Strandgård follows her progress with his eyes.

I wonder if she sings? he thinks. Like a lonely whale beneath the sea?

And as if his thoughts have touched her, she stops for a second. Breaks her endless journey. Contemplates Viktor Strandgård with her cold winter eyes. Because he is as beautiful as an icon lying there, to tell the truth, with the dark blood like a halo round his long, fair, St. Lucia hair. He can’t feel his legs anymore. He is getting drowsy. There is no pain.

Curiously enough it is his previous death he is thinking of as he lies there looking into the eye of the dragon. That time in the late winter when he came cycling down the long bank toward the crossroads at Adolf Hedinsvägen and Hjalmar Lundbohmsvägen. Happy and redeemed, his guitar on his back. He remembers how the wheels of his bicycle skidded helplessly on the ice as he tried desperately to brake. How he saw the woman in the red Fiat Uno coming from the right. How they stared at each other, the realization in the other’s eyes; now it’s happening, the icy slide toward death.

With that picture in his mind’s eye Viktor Strandgård dies for the second time in his life. Footsteps approach, but he doesn’t hear them. His eyes do not have to see the gleam of the knife once again. His body lies like an empty shell on the floor of the church; it is stabbed over and over again. And the dragon resumes her journey across the heavens, unmoved.

Monday, February 17

Rebecka Martinsson was woken by her own sharp intake of breath as fear stabbed through her body. She opened her eyes to darkness. Just between the dream and the waking, she had the strong feeling that there was someone in the flat. She lay still and listened, but all she could hear was the sound of her own heart thumping in her chest like a frightened hare. Her fingers fumbled for the alarm clock on the bedside table and found the little button to light up the face. Quarter to four. She had gone to bed four hours ago and this was the second time she had woken up.

It’s the job, she thought. I work too hard. That’s why my thoughts go round and round at night, like a hamster on a squeaking wheel.

Her head and the back of her neck were aching. She must have been grinding her teeth in her sleep. Might as well get up. She wound the duvet around her and went into the kitchen. Her feet knew the way without her needing to switch on the light. She put on the coffee machine and the radio. Bellman’s music played over and over as the water ran through the filter and Rebecka showered.

Her long hair could dry in its own time. She drank her coffee while she was getting dressed. Over the weekend she had ironed her clothes for the week and hung them up in the wardrobe. Now it was Monday. On Monday’s hanger was an ivory blouse and a navy blue Marella suit. She sniffed at the tights she’d been wearing the previous day; they’d do. They’d gone a bit wrinkly around the ankles, but if she stretched them and tucked them under her feet it wouldn’t show. She’d just have to make sure she didn’t kick her shoes off during the day. It didn’t bother her; it was only worth spending time worrying about your underwear and your tights if you thought somebody was going to be watching you get undressed. Her underwear had seen better days and was turning gray.

An hour later she was sitting at her computer in the office. The words flowed through her mind like a clear mountain stream, down her arms and out through her fingers, flying over the keyboard. Work soothed her mind. It was as if the morning’s unpleasantness had been blown away.

It’s strange, she thought. I moan and complain like all the other young lawyers about how unhappy the job makes me. But I feel a sense of peace when I’m working. Happiness, almost. It’s when I’m not working I feel uneasy.

The light from the street below forced its way with difficulty through the tall barred windows. You could still make out the sound of individual cars among the noise below, but soon the street would become a single dull roar of traffic. Rebecka leaned back in her chair and clicked on “print.” Out in the dark corridor the printer woke up and got on with the first task of the day. Then the door into reception banged. She sighed and looked at the clock. Ten to six. That was the end of her peace and quiet.

She couldn’t hear who had come in. The thick carpets in the corridor deadened the sound of footsteps, but after a while the door of her room opened.

“Am I disturbing you?” It was Maria Taube. She pushed the door open with her hip, balancing a mug of coffee in each hand. Rebecka’s copy was jammed under her right arm.

Both women were newly qualified lawyers with special responsibility for tax laws, working for Meijer & Ditzinger. The office was at the very top of a beautiful turn-of-the-century building on Birger Jarlsgatan. Semi-antique Persian carpets ran the length of the corridors, and here and there stood imposing sofas and armchairs in attractively worn leather. Everything exuded an air of experience, influence, money and competence. It was an office that filled clients with an appropriate mixture of security and reverence.

“By the time you die you must be so tired you hope there won’t be any sort of afterlife,” said Maria, and put a mug of coffee on Rebecka’s desk. “But of course that won’t apply to you, Maggie Thatcher. What time did you get here this morning? Or haven’t you been home at all?”

They’d both worked in the office on Sunday evening. Maria had gone home first.

“I’ve only just got here,” lied Rebecka, and took her copy out of Maria’s hand.

Maria sank down into the armchair provided for visitors, kicked off her ridiculously expensive leather shoes and drew her legs up under her body.

“Terrible weather,” she said.

Rebecka looked out the window with surprise. Icy rain was hammering against the glass. She hadn’t noticed earlier. She couldn’t remember if it had been raining when she came into work. In fact, she couldn’t actually remember whether she’d walked or taken the Underground. She gazed in a trance at the rain pouring down the glass as it beat an icy tattoo.

Winter in Stockholm, she thought. It’s hardly surprising that you shut down your brain when you’re outside. It’s different up at home, the blue shining midwinter twilight, the snow crunching under your feet. Or the early spring, when you’ve skied along the river from Grandmother’s house in Kurravaara to the cabin in Jiekajärvi, and you sit down and rest on the first patch of clear ground where the snow has melted under a pine tree. The tree bark glows like red copper in the sun. The snow sighs with exhaustion, collapsing in the warmth. Coffee, an orange, sandwiches in your rucksack.

The sound of Maria’s voice drew her back. Her thoughts scrabbled and tried to escape, but she pulled herself together and met her colleague’s raised eyebrows.

“Hello! I asked if you were going to listen to the news.”

“Yes, of course.”

Rebecka leaned back in her chair and stretched out her arm to the radio on the windowsill.

Lord, she’s thin, thought Maria, looking at her colleague’s rib cage as it protruded from under her jacket. You could play a tune on those ribs.

Rebecka turned the radio up and both women sat with their coffee cups cradled between their hands, heads bowed as if in prayer.

Maria blinked. It felt as if something were scratching her tired eyes. Today she had to finish the appeal for the county court in the Stenman case. Måns would kill her if she asked him for more time. She felt a burning pain in her midriff. No more coffee before lunch. You sat here like a princess in a tower, day and night, evenings and weekends, in this oh-so-charming office with all its bloody traditions which could go to hell, and all the pissed-up partners looking straight through your blouse while outside, life just carried on without you. You didn’t know whether you wanted to cry or start a revolution but all you could actually manage was to drag yourself home to the TV and pass out in front of its soothing, flickering screen.

It’s six o’clock and here are the morning headlines. A well-known religious leader around the age of thirty was found murdered early this morning in the church of The Source of All Our Strength in Kiruna. The police in Kiruna are not prepared to make a statement about the murder at this stage, but during the morning they have revealed that no one has been detained so far, and the murder weapon has not yet been found. . . . A new study shows that more and more communities are ignoring their obligations, according to Social Services. . . .

Rebecka swung her chair round so quickly that she banged her hand on the windowsill. She turned the radio off with a crash and at the same time managed to spill coffee on her knee.

“Viktor,” she exclaimed. “It has to be him.”

Maria looked at her with surprise.

“Viktor Strandgård? The Paradise Boy? Did you know him?”

Rebecka avoided Maria’s gaze. Ended up staring at the coffee stain on her skirt, her expression closed and blank. Thin lips, pressed together.

“Of course I knew of him. But I haven’t been home to Kiruna for years. I don’t know anybody up there anymore.”

Maria got up from the armchair, went over to Rebecka and pried the coffee cup from her colleague’s stiff hands.

“If you say you didn’t know him, that’s fine by me, but you’re going to faint in about thirty seconds. You’re as white as a sheet. Bend over and put your head between your knees.”

Like a child Rebecka did as she was told. Maria went to the bathroom and fetched paper towels to try to save Rebecka’s suit from the coffee stain. When she came back Rebecka was leaning back in her chair.

“Are you okay?” asked Maria.

“Yes,” answered Rebecka absently, and looked on helplessly as Maria started to dab at her skirt with a damp towel. “I did know him,” she said.

“Well, I didn’t exactly need a lie detector,” said Maria without looking up. “Are you upset?”

“Upset? I don’t know. Frightened, maybe.”

Maria stopped her frantic dabbing.

“Frightened of what?”

“I don’t know. That somebody will—”

The telephone burst in with its shrill signal before Rebecka could finish. She jumped and stared at it, but didn’t pick it up. After the third ring Maria answered. She put her hand over the receiver so that the person on the other end couldn’t hear her, and whispered:

“It’s for you and it must be from Kiruna, because there’s a Moomin troll on the other end.”

When Inspector Anna-Maria Mella’s telephone rang, she was already awake. The winter moon filled the room with its chilly white light. The birch trees outside the window drew blue shadow pictures on the walls with their bent and aching limbs. As soon as the phone started to ring, she picked it up.

“It’s Sven-Erik—were you awake?”

“Yes, but I’m in bed. What is it?”

She heard Robert sigh and glanced in his direction. Had he woken up? No, his breathing became deep and regular again. Good.

“Suspected murder in The Source of All Our Strength church,” said Sven-Erik.

“So? I’m on desk duty since Friday, in case you’ve forgotten.”

“I know” Sven-Erik’s voice sounded troubled—“but bloody hell, Anna-Maria, this is something else. You could just come and have a look. The forensic team will be finished soon, and we can go in. I’ve got Viktor Strandgård lying here, and it looks like a slaughterhouse. I’d guess we’ve got about an hour before every bloody TV station is here with cameras and the whole circus.”

“I’ll be there in twenty minutes.”

There’s a turn-up, she thought. Sven-Erik ringing to ask me for help. He’s changed.

Sven-Erik didn’t answer, but Anna-Maria heard his suppressed sigh of relief just before he put the phone down.

She turned to Robert and gazed at his sleeping face. His cheek was resting on the back of his hand and his red lips were parted slightly. She found it irresistibly sexy that a few strands of gray had started to appear in his straggling moustache and at his temples. Robert himself used to stand in front of the bathroom mirror looking anxiously at his receding hairline.

“The desert is spreading,” he would say ruefully.

She kissed him on the mouth. Her stomach got in the way, but she managed it. Twice.

“I love you,” he assured her, still asleep. His hand fumbled under the sheet to draw her close, but by then she had already managed to sit upright on the edge of the bed. All of a sudden she was desperate for a pee. Her bladder was bursting all the time. She’d already been to the bathroom twice during the night.

Quarter of an hour later Anna-Maria climbed out of her Ford Escort in the car park below The Source of All Our Strength church. It was still bitterly cold. The air pinched and nipped at her cheeks. If she breathed through her mouth her throat and lungs hurt. If she breathed through her nose the fine hairs in her nostrils froze when she inhaled. She wound her scarf around to cover her mouth and looked at her watch. Half an hour max; any longer and the car wouldn’t start. It was a big parking lot with spaces for at least four hundred cars. Her light-red Escort looked small and insignificant beside Sven-Erik Stålnacke’s Volvo 740. A radio car was parked next to Sven-Erik’s Volvo. Apart from that there were only a dozen or so cars, completely covered in snow. The forensic team must have gone already. She started to walk up the narrow path to the church on Sandstensberget. The frost lay like icing on the birch trees, and right at the top of the hill the mighty Crystal Church soared up into the night sky, surrounded by stars and planets. It stood there like a gigantic illuminated ice cube, shimmering with the Aurora Borealis.

All bloody show, she thought as she struggled up the bank. This lot are rolling in money; they ought to be giving some of their cash to Save the Children instead. But I suppose it’s more fun to sing gospel songs in a huge church than to dig wells in Africa.

In the distance she could see her colleagues Sven-Erik Stålnacke, Sergeant Tommy Rantakyrö and Inspector Fred Olsson outside the church door. Sven-Erik, bareheaded as usual, was standing quite still, leaning slightly backwards with his hands deep in the warm pockets of his fleece. The two younger men were bounding about like excited puppies. She couldn’t hear them, but she could see Rantakyrö’s and Olsson’s eager chatter coming out of their mouths like white bubbles. The puppies barked happily in greeting as soon as they caught sight of her.

“Hi,” yapped Tommy Rantakyrö, “how’s it going?”

“Fine,” she called back cheerfully.

“Soon we’ll be saying hello to your stomach first, then you’ll turn up quarter of an hour later,” said Fred Olsson.

Anna-Maria laughed.

She met Sven-Erik’s serious gaze. Small icicles had formed in his walrus moustache.

“Thanks for coming,” he said. “I hope you’ve had breakfast, because what’s in there won’t exactly give you an appetite. Shall we go in?”

“Do you want us to wait for you?”

Fred Olsson was stamping his feet up and down in the snow. He was looking from Sven-Erik to Anna-Maria and back again. Sven-Erik was supposed to be taking over during Anna-Maria’s leave, so technically he was in charge now. But since Anna-Maria was here as well it was a bit difficult to know who was making the decisions.

Anna-Maria kept quiet and looked at Sven-Erik. She was only there to keep him company.

“It would be good if you could hang on,” said Sven-Erik, “so we don’t suddenly get somebody coming along who has no business here before the body has been collected. But by all means come and stand inside the door if you’re cold.”

“Hell no, we can stand outside, I just wondered, that’s all,” Fred Olsson assured them.

“No problem.” Tommy Rantakyrö grinned with blue lips. “We’re men after all. Men don’t feel the cold.”

Sven-Erik went into the church right behind Anna-Maria and pulled the heavy door shut behind them. They walked slowly through the cloakroom, slumbering in the twilight. Long ranks of empty coat hangers rattled like an out-of-tune glockenspiel, set in motion by the draught as the cold air outside met the warmth inside. Two swing doors led into the main body of the church. Sven-Erik instinctively lowered his voice as they went in.

“It was Viktor Strandgård’s sister who rang the main office around three. She’d found him dead and she used the phone in the pastor’s office.”

“Where is she? At the station?”

“Well, no. We don’t know where she is. I left instructions to get somebody out there looking for her. There was nobody in the church when Tommy and Freddy got here.”

“What did the technicians say?”

“Look but don’t touch.”

The body was lying in the middle of the central aisle. Anna-Maria stopped a little way from it.

“Fucking hell,” she burst out.

“I did tell you,” said Sven-Erik, who was standing just behind her.

Anna-Maria pulled a little tape recorder from the inside pocket of her jacket. She hesitated for a moment. She usually spoke into it rather than making notes. But this wasn’t really her case. Maybe she ought to keep quiet and just sort of go along with Sven-Erik?

Don’t go making everything so complicated, she told herself, and switched on the tape recorder without even looking at her colleague.

“The time is five thirty-five,” she said into the microphone. “It’s the sixteenth, no seventeenth, of February. I’m standing in The Source of All Our Strength church and looking at someone who, as far as we know at the moment, is Viktor Strandgård, generally known as the Paradise Boy. The dead man is lying in the middle of the aisle. He appears to have been well and truly slit open, because he absolutely stinks and the carpet beneath the body is wet. This wetness is presumably blood, but it’s a little difficult to tell because he is lying on a red carpet. His clothes are also covered in blood and it isn’t possible to see very much of the wound in his stomach; it does seem, however, that some of his intestines are protruding, but the doctor can confirm that later. He’s wearing jeans and a jumper. The soles of his shoes are dry and the carpet under his shoes is not wet. His eyes have been gouged out. . . .”

Anna-Maria broke off and switched off the tape recorder. She moved round the body and bent over the face. She had been about to say that he made a beautiful corpse, but there were limits to what she could think aloud in front of Sven-Erik. The dead man’s face made her think of King Oedipus. She had seen the play on video at school. At the time she hadn’t been particularly affected by the scene where he put out his own eyes, but now the image came back to her with remarkable clarity. She needed to pee again. And she mustn’t forget about the car. Best get going. She switched on the tape recorder again.

“The eyes have been gouged out and the long hair is covered in blood. There must be a wound to the back of the head. There is a cut on the right of the neck, but no bleeding, and the hands are missing. . . .”

Anna-Maria turned inquiringly to Sven-Erik, who was pointing toward the rows of chairs. She bent down with difficulty and looked along the floor among the chairs.

“Oh, I see, one hand is lying three meters away under the chairs. But where’s the other?”

Sven-Erik shrugged.

“None of the chairs has been overturned,” she continued. “There are no indications of a struggle; what do you think, Sven-Erik?”

“No,” replied Sven-Erik, who disliked speaking into the tape recorder.

“Who took the photos?”

“Simon Larsson.”

Good, she thought. That meant they would have good pictures.

“Otherwise the church is tidy,” she went on. “This is the first time I’ve been in here. There are hundreds of frosted lamps along those sections of the walls that are not made of glass bricks. How high would it be? Must be more than ten meters. Huge windows in the roof. Blue chairs in rows, straight as a die. How many people would fit in here? Two thousand?”

“Plus the pulpit,” said Sven-Erik.

He wandered round and allowed his gaze to sweep over every surface like a vacuum cleaner.

Anna-Maria turned and looked at the pulpit towering behind her. The organ pipes soared upward and met their own reflection in the windows in the roof. It was an impressive sight.

“There isn’t really very much more to add,” said Anna-Maria hesitantly, as if some idea might work its way up from her subconscious and creep out through a gap in the syllables as she spoke. “There’s something . . . something that makes me feel frustrated when I look at all this. Besides the fact that this corpse is in the worst state I’ve ever seen—”

“Hey, you two! His lordship the assistant chief prosecutor is on his way up the hill.”

Tommy Rantakyrö had stuck his head in through the doorway.

“Who the hell rang him?” asked Sven-Erik, but Tommy had already disappeared.

Anna-Maria looked at him. Four years ago when she became team leader Sven-Erik had hardly spoken to her for the first six months. He had been deeply hurt because she had got the job he wanted. And now that he’d found his feet as her second in command, he didn’t want to take that extra step forward. She made a mental note to give him a pep talk later. But now he’d just have to manage by himself. Just as Assistant Chief Prosecutor Carl von Post stormed in through the door, she gave Sven-Erik an encouraging look.

“What the fuck is going on here?” yelled von Post.

He yanked off his fur hat and his hand went up to his mane of curly hair from sheer force of habit. He stamped his feet. The short walk up from the car park was enough to turn his feet to ice in his smart shoes from Church’s. He strode up to Anna-Maria and Sven-Erik but recoiled when he caught sight of the body on the floor.

“Oh, bloody hell,” he burst out, and looked anxiously down at his shoes to check whether he might have got them dirty.

“Why didn’t somebody ring me?” he went on, turning to Sven-Erik. “From now on I’m taking over the investigation, and you can expect a serious talk with the chief if you’ve been keeping me in the dark.”

“Nobody’s been keeping you in the dark, we didn’t know what had happened and we still don’t really know anything,” ventured Sven-Erik.

“Crap!” snapped the prosecutor. “And what the hell are you doing here?”

This was directed at Anna-Maria, who was standing in silence gazing at Viktor Strandgård’s mutilated arms.

“I rang her,” explained Sven-Erik.

“I see,” said von Post through clenched teeth. “So you rang her, but not me.”

Sven-Erik said nothing, and Carl von Post looked at Anna-Maria, who raised her eyes and met his gaze calmly.

Carl von Post clamped his teeth together so hard that his jaws ached. He’d always had a problem with this midget of a policewoman. She seemed to have her male colleagues on the Investigation squad by the balls, and he couldn’t work out why. And just look at her. One meter fifty at the most in her stocking feet, with a long horse’s face which more or less covered half her body. At the moment she was ready for a circus freak show with her enormous belly. Like a grotesque cube, she was as broad as she was tall. It just had to be the inevitable result of generations of inbreeding in those little isolated Lapp villages.

He waved his hand in the air as if to waft away his sharp words and started on a new tack.

“How are you feeling, Anna-Maria?” he asked, pasting on a gentle and sympathetic smile.

“Fine,” she answered without expression. “And you?”

“I reckon we’ll have the press round our ears in maybe an hour or so. It’ll be all hell let loose, so tell me what you know so far about the murder and the dead man; all I know is that he was a religious celebrity.”

Carl von Post sat down on one of the blue chairs and pulled off his gloves.

“I’ll let Sven-Erik tell you,” said Anna-Maria in a laconic but not unfriendly tone. “I’m supposed to be on desk duty until my time comes. I came along with Sven-Erik because he asked me to, and because two pairs of eyes see more than . . . well, you know all that. And now I need to pee. If you’ll excuse me.”

She noticed with satisfaction the pained smile on von Post’s face as she went off to the bathroom. To think that the word “pee” could offend his ears quite so much. She wouldn’t mind betting that his wife made sure she directed the stream of liquid onto the porcelain when she peed so his delicate little ears wouldn’t be troubled by the sound of piddling. Bloody man.

“Well,” said Sven-Erik when Anna-Maria had disappeared, “you can see things for yourself, and we don’t know much more. Somebody has killed him. And they’ve done it very thoroughly, I must say. The dead man is Viktor Strandgård, or the Paradise Boy as he’s known. He’s the main attraction in this huge church community. Nine years ago he was involved in a terrible car accident. He died at the hospital. His heart stopped and everything, but they got him back, and he could tell them all about what had happened during the operation and when they were trying to resuscitate him, that the doctor had dropped his glasses and so on. And then he said he’d been in heaven. He met angels, and Jesus. Anyway, one of the nurses who’d been involved in the operation was saved, and the woman who ran into him, and suddenly the whole of Kiruna was one big revivalist meeting. The three biggest free churches joined together to make one new church, The Source of All Our Strength. The congregation grew and in recent years they’ve built this church, started their own school and their own nursery, and held huge revivalist meetings. Tons of money is pouring in, and people come here from all over the world. Viktor Strandgård is—or was, I should say— employed by the church full-time, and he’s written a best seller. . . .”

“Himlen Tur och Retur, Heaven and Back.”

“That’s the one. He’s their golden calf, he’s been in all the papers, even Expressen and Aftonbladet, so there’s bound to be a lot written now. And the TV cameras will be up here.”

“Exactly,” said von Post, and stood up, looking impatient. “I don’t want anyone leaking information to the press. I’ll take over all contact with the media and I want you to report to me on a regular basis; anything that emerges during interrogation and so on, is that clear? Everything is to be passed on to me. When the journalists start asking questions you can say I’ll be holding a press conference on the steps of the church at twelve midday today. What’s your next move?”

“We need to get hold of the sister, she was the one who found the body; then we need to speak to the three pastors. The medical examiner is on his way from Luleå; he should be here any minute now.”

“Good. I want a report on the cause of death and a credible version of the course of events leading up to it at eleven-thirty, so be by the phone then. That’s all. If you’re done here I’ll just take a look around on my own for a bit.”

Oh, come on,” said Anna-Maria to Sven-Erik Stålnacke. “This has got to be better than sitting around interviewing pissed-up snowmobile riders.”

Her Ford Escort wouldn’t start, and Sven-Erik was giving her a lift home.

It was just as well, she thought; he needed encouragement so that he didn’t get fed up with the job.

“It’s that bastard von Pisspot,” Sven-Erik replied with a grimace. “As soon as I have anything to do with him I just feel like saying sod the lot of it, and just going through the motions every day until it’s time to go home.”

“Well, don’t think about him now. Think about Viktor Strandgård instead. The lunatic who killed him is out there somewhere, and you’re going to find him. Let that pompous old fool scream and shout and talk to the newspapers. The rest of us know who actually does all the work.”

“How can I not think about him? He’s watching me like a hawk all the time.”

“I know.”

She looked out through the car window. The houses still lay sleeping in the darkness of the streets, with just an occasional light in a window. The orange paper Advent stars were still hanging here and there. This year nobody had burned to death. There had been fights and the usual dose of misery, but no worse than usual. She felt slightly sick. Hardly surprising. She’d been up for a good hour and had eaten nothing. She realized she wasn’t concentrating on what Sven-Erik was saying, and rewound her memory to catch up. He’d asked how she’d managed to work with von Post.

“We never actually had that much to do with each other,” she said.

“Look, I could really do with your help, Anna-Maria. There’s going to be a hell of a lot of pressure on those of us working on this case, without that bully on top of everything else. I could do with a colleague’s support right now.”

“That sounds like blackmail to me.” Anna-Maria couldn’t help laughing.

“I’ll do whatever it takes. Blackmail, threats. In any case, it’s good for you to get a bit of exercise. You could at least be there and talk to the sister when we find her. Just help me get started.”

“Fine, ring me when you’ve found her.”

Sven-Erik bent forward over the steering wheel and looked up at the night sky.

“Just look at the moon,” he said with a smile. “I should be out there hunting foxes.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"For those who eschew exotic travel in favor of the familiar hammock, there's nothing better than a well-written and well-translated story from some place you'll probably never visit. Sun Storm is that story and more."—grade, Rocky Mountain News

"Impressive ... [A] sure-handed thriller from a talented first novelist."—Booklist

From the Hardcover edition.

"Impressive ... [A] sure-handed thriller from a talented first novelist."—Booklist

From the Hardcover edition.