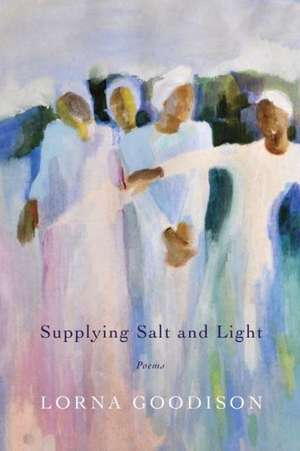

Supplying Salt and Light

Autor Lorna Goodisonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 mar 2013

The title sets the tone for poems about backgrounds and outlines and shadows and sources of light. This extraordinary book -- "a wide lotus on the dark waters of song" -- is filled with surprises at every turn, as a Moorish mosque becomes a cathedral in Seville, a country girl dresses in Sunday clothes to visit a Jamaican bookmobile, and a bear appears suddenly, only to slip away silently into the trees on a road in British Columbia. The heartache of Billy Holliday singing the blues, the burden of Charlie Chaplin tramping the banana walks of Jamaica's Golden Cloud, and the paintings of El Greco, the quintessential stranger, come together on the poet's pilgrimage to Heartease, guided by a limping angel and inspired by the passage-making of Dante; the book ends with a superb version of the first of his cantos, translated into the poet's Jamaican language and landscape with the gift of love.

Preț: 96.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 144

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.42€ • 19.70$ • 15.36£

18.42€ • 19.70$ • 15.36£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771035906

ISBN-10: 077103590X

Pagini: 121

Dimensiuni: 140 x 211 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 077103590X

Pagini: 121

Dimensiuni: 140 x 211 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

LORNA GOODISON is the author of two collections of short stories, eight books of poetry, and the highly acclaimed, award-winning memoir From Harvey River: A Memoir of My Mother and Her People. She has received much international recognition, including the Musgrave Gold Medal. Born in Jamaica, Goodison has taught at the University of Toronto and now teaches at the University of Michigan. She divides her time between Ann Arbor, Toronto, and Halfmoon Bay, British Columbia.

Extras

To Make Various Sorts of Black

According to The Craftsman’s Handbook, chapter XXXVII

“Il Libro dell’ Arte” by Cennino d’Andrea Cennini

who tells us there are several kinds of black colours.

First, there is a black derived from soft black stone.

It is a fat colour; not hard at heart, a stone unctioned.

Then there is a black that is obtained from vine twigs.

Twigs that choose to abide on the true vine

offering up their bodies at the last to be burned,

then quenched and worked up, they can live again

as twig of the vine black; not a fat, more of a lean

colour, favoured alike by vinedressers and artists.

There is also the black that is scraped from burnt shells.

Markers of Atlantic’s graves.

Black of scorched earth, of torched stones of peach;

twisted trees that bore strange fruit.

And then there is the black that is the source of light

from a lamp full of oil such as any thoughtful guest

waiting for bride and groom who cometh will have.

A lamp you light and place underneath ߝ not a bushel ߝ

but a good clean everyday dish that is fit for baking.

Now bring the little flame of the lamp up to the under

surface of the earthenware dish (say a distance of two

or three fingers away) and the smoke that emits

from that small flame will struggle up to strike at clay.

Strike till it crowds and collects in a mess or a mass;

now wait, wait a while please, before you sweep this

colour ߝ now sable velvet soot ߝ off onto any old paper

or consign it to shadows, outlines, and backgrounds.

Observe: it does not need to be worked up nor ground;

it is just perfect as it is. Refill the lamp, Cennini says.

As many times as the flame burns low, refill it.

Reporting Back to Queen Isabella

When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: “The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.”

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he ’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.

You Should Go to Toledo

I’d stared hard at the tongues of flame

over the heads of the disciples; I felt

a dry heat catch fire in my fontanelle.

“El Grec” the docent in the Prado called

him; a stranger in Spain all his days.

“What is it you like about him?” the one

who came from the dark night inquires.

So I say this:

The way his figures struggle and stretch

till they pass the mandatory seven heads

must be about grasp exceeding reach.

The overturning of my temples,

the slant sideways of seeing that open

as I approach his door-sized canvases.

And his storm-at-sea-all-dolorous blue;

and his bottle-green washing to chartreuse;

and his maroon stains of dried oxblood.

The verdigris undersheen of the black coat,

white lace foaming at the throat and wrist

of a knight with one hand to his chest.

How I cling to the hem of the garment

of La Trinidad’s broad-beam angel

who resembles my mother when she was

young, strong, and healthy ߝ body able

to ease the crucified from off the cross.

And he who separated from the shades

and sat at table with us in a late night place

redolent with olive oil and baccalau said:

“Then you should go to Toledo.”

According to The Craftsman’s Handbook, chapter XXXVII

“Il Libro dell’ Arte” by Cennino d’Andrea Cennini

who tells us there are several kinds of black colours.

First, there is a black derived from soft black stone.

It is a fat colour; not hard at heart, a stone unctioned.

Then there is a black that is obtained from vine twigs.

Twigs that choose to abide on the true vine

offering up their bodies at the last to be burned,

then quenched and worked up, they can live again

as twig of the vine black; not a fat, more of a lean

colour, favoured alike by vinedressers and artists.

There is also the black that is scraped from burnt shells.

Markers of Atlantic’s graves.

Black of scorched earth, of torched stones of peach;

twisted trees that bore strange fruit.

And then there is the black that is the source of light

from a lamp full of oil such as any thoughtful guest

waiting for bride and groom who cometh will have.

A lamp you light and place underneath ߝ not a bushel ߝ

but a good clean everyday dish that is fit for baking.

Now bring the little flame of the lamp up to the under

surface of the earthenware dish (say a distance of two

or three fingers away) and the smoke that emits

from that small flame will struggle up to strike at clay.

Strike till it crowds and collects in a mess or a mass;

now wait, wait a while please, before you sweep this

colour ߝ now sable velvet soot ߝ off onto any old paper

or consign it to shadows, outlines, and backgrounds.

Observe: it does not need to be worked up nor ground;

it is just perfect as it is. Refill the lamp, Cennini says.

As many times as the flame burns low, refill it.

Reporting Back to Queen Isabella

When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: “The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.”

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he ’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.

You Should Go to Toledo

I’d stared hard at the tongues of flame

over the heads of the disciples; I felt

a dry heat catch fire in my fontanelle.

“El Grec” the docent in the Prado called

him; a stranger in Spain all his days.

“What is it you like about him?” the one

who came from the dark night inquires.

So I say this:

The way his figures struggle and stretch

till they pass the mandatory seven heads

must be about grasp exceeding reach.

The overturning of my temples,

the slant sideways of seeing that open

as I approach his door-sized canvases.

And his storm-at-sea-all-dolorous blue;

and his bottle-green washing to chartreuse;

and his maroon stains of dried oxblood.

The verdigris undersheen of the black coat,

white lace foaming at the throat and wrist

of a knight with one hand to his chest.

How I cling to the hem of the garment

of La Trinidad’s broad-beam angel

who resembles my mother when she was

young, strong, and healthy ߝ body able

to ease the crucified from off the cross.

And he who separated from the shades

and sat at table with us in a late night place

redolent with olive oil and baccalau said:

“Then you should go to Toledo.”

Recenzii

"[Goodison's poetry] continually surprises with its insistently elegant, spiritual core and crystalline intelligence." -- Publishers Weekly

"The fluency of her rhythms, the dazzling imagery and the celebratory impulse all make [Goodison's poetry] a distinguished, outstanding pleasure." -- Poetry Review

"[Goodison is] among the finest poets writing today." -- World Literature Today

"Goodison advances from strength to strength. . . . [She focuses] the diamond lens of her incantatory verse on the culture and people of her homeland in the Caribbean. . . ." -- Booklist (starred review)

"The fluency of her rhythms, the dazzling imagery and the celebratory impulse all make [Goodison's poetry] a distinguished, outstanding pleasure." -- Poetry Review

"[Goodison is] among the finest poets writing today." -- World Literature Today

"Goodison advances from strength to strength. . . . [She focuses] the diamond lens of her incantatory verse on the culture and people of her homeland in the Caribbean. . . ." -- Booklist (starred review)