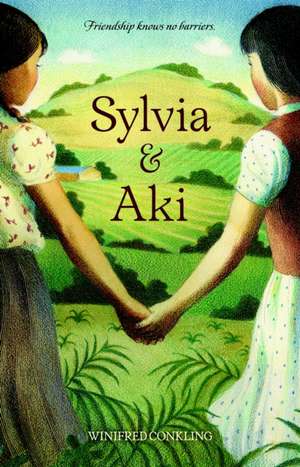

Sylvia & Aki

Autor Winifred Conklingen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 iul 2013 – vârsta de la 9 până la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Americas Award for Children & Young Adult Literature (2012), Jane Addams Children's Book Award (2012), Kentucky Bluegrass Award (2013)

Preț: 42.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 64

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.20€ • 8.53$ • 6.77£

8.20€ • 8.53$ • 6.77£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781582463452

ISBN-10: 158246345X

Pagini: 151

Dimensiuni: 132 x 191 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

ISBN-10: 158246345X

Pagini: 151

Dimensiuni: 132 x 191 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Notă biografică

WINIFRED CONKLING studied journalism at Northwestern University and spent the next 25 years writing nonfiction for adult readers, including articles for Consumer Reports magazine and more than 30 nonfiction books. As part of her transition to writing for young people, she is working toward her Master of Fine Arts in Writing for Children and Young Adults from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Sylvia & Aki is her first work for children.

Extras

Sylvia:

"Excuse me, ma’am," Aunt Soledad said to the secretary. "May I have several more forms? For my brother’s children?"

The woman stopped typing again. She looked at Sylvia and her brothers as if noticing them for the first time. "Are these your children?"

"No," Aunt Soledad said. "These two are mine." She rested one hand on Alice’s shoulder and the other on Virginia’s. "They’ll be entering third and fourth grade." Sylvia looked at her cousins. They had fair skin and wore their long wavy brown hair in tight curls tied back from their faces with navy ribbons.

"These are my brother’s children," Aunt Soledad said, gesturing at Sylvia and her two brothers, all three alike with warm brown skin, dark hair, and dark eyes. Jerome and Gonzalo had broad, friendly smiles and neatly combed hair. Sylvia wore her own hair in two straight braids, with a red bow pinned above her right ear. She tried to smile, too, but something in the way the woman was looking at them made her uneasy.

"What are their names?" the secretary asked with a sigh.

"Mendez: Sylvia, Gonzalo junior, and Jerome."

The woman held up her hand to interrupt Sylvia’s aunt. "The Mendez children will need to register at Hoover School, the Mexican school."

"What? No," Aunt Soledad objected. "I want all of the children in the same school. Both families live here in Westminster."

"Mexican children go to the Mexican school," the woman insisted.

"But we live here," Aunt Soledad repeated. "All of us. Together." Sylvia and her family lived in the main house on the farm, while Aunt Soledad and her family lived in one of the smaller caretakers’ houses.

"I’m sorry, but there is nothing I can do about the rules," the woman said, noisily shutting the desk drawer.

Aki:

The trouble started on a Sunday afternoon. It was December 7, 1941. Aki sat at the dining room table with her math homework spread out before her. It was problems in long division: two-digit divisors into four-digit dividends, with remainders. From time to time Aki repeated her teacher’s instructions: "Find the quotient; check your work." In the kitchen, her mother cleaned up the lunch dishes while the radio played a piano sonata. Aki’s head was filled with numbers and music.

And then the music stopped.

"We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin," said a man’s deep, serious voice. "The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by air."

Aki laid down her pencil and went to the kitchen. Her mother stood by the sink with her right hand over her mouth. They both stared at the radio, listening closely to every word. Together they learned that at 7:53 a.m. Hawaii time, Japanese airplanes had bombed the United States naval station at Pearl Harbor. No one knew how many Americans were dead or how many ships had been destroyed.

When the report ended, Aki asked, "What does this mean?"

"War," her mother said. "It means there will be war."

From the Hardcover edition.

"Excuse me, ma’am," Aunt Soledad said to the secretary. "May I have several more forms? For my brother’s children?"

The woman stopped typing again. She looked at Sylvia and her brothers as if noticing them for the first time. "Are these your children?"

"No," Aunt Soledad said. "These two are mine." She rested one hand on Alice’s shoulder and the other on Virginia’s. "They’ll be entering third and fourth grade." Sylvia looked at her cousins. They had fair skin and wore their long wavy brown hair in tight curls tied back from their faces with navy ribbons.

"These are my brother’s children," Aunt Soledad said, gesturing at Sylvia and her two brothers, all three alike with warm brown skin, dark hair, and dark eyes. Jerome and Gonzalo had broad, friendly smiles and neatly combed hair. Sylvia wore her own hair in two straight braids, with a red bow pinned above her right ear. She tried to smile, too, but something in the way the woman was looking at them made her uneasy.

"What are their names?" the secretary asked with a sigh.

"Mendez: Sylvia, Gonzalo junior, and Jerome."

The woman held up her hand to interrupt Sylvia’s aunt. "The Mendez children will need to register at Hoover School, the Mexican school."

"What? No," Aunt Soledad objected. "I want all of the children in the same school. Both families live here in Westminster."

"Mexican children go to the Mexican school," the woman insisted.

"But we live here," Aunt Soledad repeated. "All of us. Together." Sylvia and her family lived in the main house on the farm, while Aunt Soledad and her family lived in one of the smaller caretakers’ houses.

"I’m sorry, but there is nothing I can do about the rules," the woman said, noisily shutting the desk drawer.

Aki:

The trouble started on a Sunday afternoon. It was December 7, 1941. Aki sat at the dining room table with her math homework spread out before her. It was problems in long division: two-digit divisors into four-digit dividends, with remainders. From time to time Aki repeated her teacher’s instructions: "Find the quotient; check your work." In the kitchen, her mother cleaned up the lunch dishes while the radio played a piano sonata. Aki’s head was filled with numbers and music.

And then the music stopped.

"We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin," said a man’s deep, serious voice. "The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by air."

Aki laid down her pencil and went to the kitchen. Her mother stood by the sink with her right hand over her mouth. They both stared at the radio, listening closely to every word. Together they learned that at 7:53 a.m. Hawaii time, Japanese airplanes had bombed the United States naval station at Pearl Harbor. No one knew how many Americans were dead or how many ships had been destroyed.

When the report ended, Aki asked, "What does this mean?"

"War," her mother said. "It means there will be war."

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Americas Award for Children & Young Adult Literature Commended, 2012

- Jane Addams Children's Book Award Winner, 2012

- Kentucky Bluegrass Award Nominee, 2013

- Volunteer State Book Awards Nominee, 2013

- Nevada Young Readers' Award Nominee, 2014

- Maud Hart Lovelace Book Award Nominee, 2015