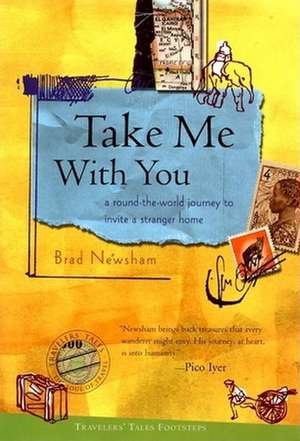

Take Me with You: A Round-The-World Journey to Invite a Stranger Home: Travelers' Tales Footsteps (Hardcover)

Autor Brad Newshamen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 iul 2000

Preț: 100.18 lei

Preț vechi: 124.95 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 150

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.18€ • 20.84$ • 16.12£

19.18€ • 20.84$ • 16.12£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781885211514

ISBN-10: 1885211511

Pagini: 350

Ilustrații: B&W photos

Dimensiuni: 150 x 211 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Travelers' Tales Guides

Seria Travelers' Tales Footsteps (Hardcover)

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1885211511

Pagini: 350

Ilustrații: B&W photos

Dimensiuni: 150 x 211 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Travelers' Tales Guides

Seria Travelers' Tales Footsteps (Hardcover)

Locul publicării:United States

Descriere

Newsham tells the story of his 100-day journey through the Philippines, India, Egypt, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, as he seeks just the right person to bring back to America to visit. Photos.

Extras

One Hundred Days

When it is a question of money, everyone is of the same religion. — Voltaire

T he cab driver glanced back at me. “You...” he said. “America?”

It was a Wednesday evening in early November—the pleasant, dry season in the Philippines—and a breeze with the feel of warm coconut milk was pouring through my open window. I’d studied a map on the plane: the blackness beyond the row of palm trees to our left would be Manila Bay. To our right a congregation of burlap lean-tos overflowed onto the sidewalk, and, between two of them, a woman was cooking something over a smoky fire.

“Yes,” I said. “America. San Francisco.”

“Ah, Cah-lee-for-nee-ah!” said the driver. “California best.”

He slowed to acknowledge a red traffic signal, then, reassured, sailed through it. Above the meter were a license and photo identifying the taxi as Golden Cab Number Two (it was painted black) and the driver as Mr. Alfredo Errabo. At the airport Mr. Errabo had agreed to take me to Manila’s Ermita district where, according to my guidebook, hotel rooms cost less than $10 a night.

In the past I might have insisted on something cheaper, $5 or less, but this was the best-financed trip I’d ever had. A couple of decades had exhausted themselves since my visit to the Hindu Kush, but I had not yet become rich—by Western standards I had never even been close. But recently I had sold a book, my first, and after paying off all my debts I was left with the biggest stash of my life, $6,800. I thought: Give up my apartment, put everything in storage, and I can afford a trip. My editor had asked me to be back for publication in mid-February, and when I sat down with my calendar and counted its squares, I discovered a travel window of exactly 100 days. I studied maps of Africa and Asia and picked out several places I’d always been curious about—the Philippines, Egypt, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and South Africa—and one, India, I was eager to see again. I bought $3,000 worth of plane tickets, set aside $300 for a splurge/emergency fund, and put $1,000 into a savings account—something to come back to. This left $2,500 for expenses: 100 days at $25 a day. In the places I was headed I would be one of the wealthy.

When Mr. Errabo and I had been riding for more than ten minutes the meter read 28 pesos—a sum about equal to the cost of a medium-sized cup of coffee back home. But in San Francisco the twelve-mile trip from the airport to the Transamerica Pyramid downtown cost about $30—without a tip. I knew. Mr. Errabo and I were brothers.

“In San Francisco,” I told him, “I am a taxi driver.”

He turned to look at me, headlights from behind illuminating his gimme-a-break facial expression. “You,” he said, “taxi owner?”

“No. Taxi driver.” I raised my hands to my own imaginary steering wheel. “I drive—like you. Every day, ten hours.”

Mr. Errabo snorted. “Ten hours...”

“Yes.” I was no slouch. “Ten-hour shift.”

“In Manila,” he said, “twenty-four hours.”

“No! Nobody drives twenty-four hours. When do you sleep?”

“Sleep other day. Today I drive twenty-four hours, no sleep—maybe ten minutes sometimes. Tomorrow another man drive twenty-four hours, I sleep. Next day, I drive twenty-four hours, he sleep.” Mr. Errabo jerked the wheel back and forth three times to weave us through a series of beach ball-sized potholes. At the side of the road a group of four men and two women were clustered around a smoking car; the women held babies and waved frantically at us. Mr. Errabo ignored them. “In California, drive ten hours. How many dollars?”

Knowing full well he’d never believe it, I told him the truth: “Average day—$150.”

Mr. Errabo looked at me again, his eyes flickering like the digital figures on a calculator. “One hundred and fifty dollars!” he said. “Hah!”

We drove in silence for a while, following the line of palms and the blackness; on our right the blazing lights of the Hyatt Regency appeared, then receded, and were followed by a string of clubs and restaurants whose names—Josephine, Burger Machine—were spelled out in orange and purple neon.

“What is a good day for a Manila taxi driver?” I asked.

Mr. Errabo sighed. “For me, 300 pesos is good day. Five hundred pesos—very good day.” Enough to buy a tank of gas at home. We were not brothers, not even distant cousins.

“San Francisco taxi driver money can go Manila,” he said. “Japanese taxi driver money can go Manila. Manila taxi driver money...”—he rubbed his fingers together and spat on them—“money no goot. Manila taxi driver stay in Manila.”

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

Good Lord...I don’t know the solution of boredom. If I did, I’d be the one philosopher that had the cure for living. But I do know that about ten times as many people find their lives dull, and unnecessarily dull, as ever admit it; and I do believe that if we busted out and admitted it sometimes, instead of being nice and patient and loyal for sixty years, and then nice and patient and dead for the rest of eternity, why, maybe possibly, we might make life more fun. —Sinclair Lewis, Babbit

The next morning I was up with the soft early light, walking. Already the air was warm and muggy—short pants weather—and stepping from my six dollar hotel I caught a whiff of rotting food. Freelance garbage men sifted through the trash in the gutters to salvage empty bottles. The sidewalks were strewn with the curled shapes of unconscious people; most had thin cardboard mattresses, but many slept right on the pavement. Four little boys—five-year-olds, I guessed—slept in a heap in a doorway, arms and legs tossed over each other like ropes; they had no guardian, no mattress, no cardboard, no blankets, and only two of them wore shirts. I could hear one snoring. Two jeepneys crept past bumper to bumper—the names “Wheels of Fortune” and “California Dreamin’” painted on their sides, and the song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” cooing in perfect synchronicity from their radios.

To the traveler arriving in a new place everything seems significant: the golden light slanting over rooftops and gilding window panes on the opposite side of the street; the engine noises and garbage stench; the babble of early hawkers; the new pool of unknown lives. I looked around the street and took a deep breath that was strangely gratifying. I’d spent years sitting in my own little part of the globe wondering what this part looked like, and now here it was. The real world. And the real world does not present itself in easily absorbed, seven-minute intervals, broken by sixty-second commercial breaks; nor in groups of five eight-hour workdays separated by weekends. The real world marches at you head-on, in jerky bursts of color and boredom and trauma, reminding you that you are alive and small and not in control of anything at all.

My invite-someone-to-America idea had shaped and reshaped itself many times since that morning in Afghanistan. My present plan: When this trip was over I would surprise one of the people I had met along the way, someone who had never been out of his (or possibly her) native country, with an invitation to visit and travel around the United States with me for one month—my treat.

I was uncertain as to just how I would decide whom to invite. Maybe I would meet someone so compelling—so kind, eccentric, or just so much fun—that the choice would be obvious. But if that didn’t happen, I would simply, when I got home, drop everyone’s name into a hat and draw one out.

As I walked through the Ermita district toward Manila’s focal point, Rizal Park, arms shot up from apparently lifeless bundles, palms outstretched. I gave a peso to a man with no legs, and thought: In San Francisco a few cents is an insult.

A young woman, wearing a short skirt and swinging a tiny black purse, caught my eye and slid her tongue across her lips. Even at this hour women in high heels, black net stockings, and frilly red teddies lounged in front of twenty-four-hour bars, and stretched their smooth, peanut butter-colored limbs. Winking at me they cooed, “Hi Joe,” while young men leapt up to swing open the barroom doors. “Very nice, Joe. Very nice.” Through the front door of one darkened place I saw a searchlight slicing through banks of cigarette smoke to highlight a tiny woman in a white Day-Glo bikini, prancing on a bar top.

In ten minutes I reached Rizal Park, a wide swath of green fronting on Manila Bay. On December 30, 1896, Dr. Jose Rizal—a poet, a genius who spoke more than thirty languages, and the spiritual leader of the Filipino struggle against the Spanish—was executed in the park that now bears his name. Photographs show Rizal standing with his back to the poised firing squad, and a formally dressed mob of thousands—Spaniards and Filipinos alike—crowding around to watch. Today the execution ground is a sprawling green lawn, punctuated by flowerbeds and fountains and statues, open-air amphitheaters, and a roller rink. A sea wall, a promenade, and a row of palms lined the water’s edge, and here, hunkered down on benches or spread out on the lawn, hundreds of Filipinos had gathered to watch the mid-morning sun heat up the bay.

I bought a Manila Bulletin from a small boy and found a shaded, empty bench. I had barely opened it when four men—each with a camera, a Rizal Park baseball hat, and a badge: official rizal park photographer—lined up in front of my bench.

“Pit-chur? Next to fountain. Only fifty pesos. Very cheap.”

They stayed, pleading—“O.K., O.K. For you, forty pesos”—until I showed them my own small camera, and then they chased en masse after a French-speaking couple who had strolled by.

A front-page article described the uproar over Webster’s latest dictionary having used the phrase “domestic worker” to define the word “Filipina.” Filipinas and Filipinos everywhere were enraged and insulted. The mayor of Ermita had banned the book’s sale. The dictionary people were holding firm.

Suddenly a small open hand imposed itself between my eyes and the newspaper. A girl—barefoot, with dirt-stained cheeks, no older than six—stood in front of me, a baby boy cradled in her arms.

“No mama,” she croaked. “No papa.”

I asked what had happened to them.

“No mama,” she croaked. “No papa.” The baby gaped at me with stunned brown eyes.

Was this her brother?

“No mama. No papa.”

When it is a question of money, everyone is of the same religion. — Voltaire

T he cab driver glanced back at me. “You...” he said. “America?”

It was a Wednesday evening in early November—the pleasant, dry season in the Philippines—and a breeze with the feel of warm coconut milk was pouring through my open window. I’d studied a map on the plane: the blackness beyond the row of palm trees to our left would be Manila Bay. To our right a congregation of burlap lean-tos overflowed onto the sidewalk, and, between two of them, a woman was cooking something over a smoky fire.

“Yes,” I said. “America. San Francisco.”

“Ah, Cah-lee-for-nee-ah!” said the driver. “California best.”

He slowed to acknowledge a red traffic signal, then, reassured, sailed through it. Above the meter were a license and photo identifying the taxi as Golden Cab Number Two (it was painted black) and the driver as Mr. Alfredo Errabo. At the airport Mr. Errabo had agreed to take me to Manila’s Ermita district where, according to my guidebook, hotel rooms cost less than $10 a night.

In the past I might have insisted on something cheaper, $5 or less, but this was the best-financed trip I’d ever had. A couple of decades had exhausted themselves since my visit to the Hindu Kush, but I had not yet become rich—by Western standards I had never even been close. But recently I had sold a book, my first, and after paying off all my debts I was left with the biggest stash of my life, $6,800. I thought: Give up my apartment, put everything in storage, and I can afford a trip. My editor had asked me to be back for publication in mid-February, and when I sat down with my calendar and counted its squares, I discovered a travel window of exactly 100 days. I studied maps of Africa and Asia and picked out several places I’d always been curious about—the Philippines, Egypt, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and South Africa—and one, India, I was eager to see again. I bought $3,000 worth of plane tickets, set aside $300 for a splurge/emergency fund, and put $1,000 into a savings account—something to come back to. This left $2,500 for expenses: 100 days at $25 a day. In the places I was headed I would be one of the wealthy.

When Mr. Errabo and I had been riding for more than ten minutes the meter read 28 pesos—a sum about equal to the cost of a medium-sized cup of coffee back home. But in San Francisco the twelve-mile trip from the airport to the Transamerica Pyramid downtown cost about $30—without a tip. I knew. Mr. Errabo and I were brothers.

“In San Francisco,” I told him, “I am a taxi driver.”

He turned to look at me, headlights from behind illuminating his gimme-a-break facial expression. “You,” he said, “taxi owner?”

“No. Taxi driver.” I raised my hands to my own imaginary steering wheel. “I drive—like you. Every day, ten hours.”

Mr. Errabo snorted. “Ten hours...”

“Yes.” I was no slouch. “Ten-hour shift.”

“In Manila,” he said, “twenty-four hours.”

“No! Nobody drives twenty-four hours. When do you sleep?”

“Sleep other day. Today I drive twenty-four hours, no sleep—maybe ten minutes sometimes. Tomorrow another man drive twenty-four hours, I sleep. Next day, I drive twenty-four hours, he sleep.” Mr. Errabo jerked the wheel back and forth three times to weave us through a series of beach ball-sized potholes. At the side of the road a group of four men and two women were clustered around a smoking car; the women held babies and waved frantically at us. Mr. Errabo ignored them. “In California, drive ten hours. How many dollars?”

Knowing full well he’d never believe it, I told him the truth: “Average day—$150.”

Mr. Errabo looked at me again, his eyes flickering like the digital figures on a calculator. “One hundred and fifty dollars!” he said. “Hah!”

We drove in silence for a while, following the line of palms and the blackness; on our right the blazing lights of the Hyatt Regency appeared, then receded, and were followed by a string of clubs and restaurants whose names—Josephine, Burger Machine—were spelled out in orange and purple neon.

“What is a good day for a Manila taxi driver?” I asked.

Mr. Errabo sighed. “For me, 300 pesos is good day. Five hundred pesos—very good day.” Enough to buy a tank of gas at home. We were not brothers, not even distant cousins.

“San Francisco taxi driver money can go Manila,” he said. “Japanese taxi driver money can go Manila. Manila taxi driver money...”—he rubbed his fingers together and spat on them—“money no goot. Manila taxi driver stay in Manila.”

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

Good Lord...I don’t know the solution of boredom. If I did, I’d be the one philosopher that had the cure for living. But I do know that about ten times as many people find their lives dull, and unnecessarily dull, as ever admit it; and I do believe that if we busted out and admitted it sometimes, instead of being nice and patient and loyal for sixty years, and then nice and patient and dead for the rest of eternity, why, maybe possibly, we might make life more fun. —Sinclair Lewis, Babbit

The next morning I was up with the soft early light, walking. Already the air was warm and muggy—short pants weather—and stepping from my six dollar hotel I caught a whiff of rotting food. Freelance garbage men sifted through the trash in the gutters to salvage empty bottles. The sidewalks were strewn with the curled shapes of unconscious people; most had thin cardboard mattresses, but many slept right on the pavement. Four little boys—five-year-olds, I guessed—slept in a heap in a doorway, arms and legs tossed over each other like ropes; they had no guardian, no mattress, no cardboard, no blankets, and only two of them wore shirts. I could hear one snoring. Two jeepneys crept past bumper to bumper—the names “Wheels of Fortune” and “California Dreamin’” painted on their sides, and the song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” cooing in perfect synchronicity from their radios.

To the traveler arriving in a new place everything seems significant: the golden light slanting over rooftops and gilding window panes on the opposite side of the street; the engine noises and garbage stench; the babble of early hawkers; the new pool of unknown lives. I looked around the street and took a deep breath that was strangely gratifying. I’d spent years sitting in my own little part of the globe wondering what this part looked like, and now here it was. The real world. And the real world does not present itself in easily absorbed, seven-minute intervals, broken by sixty-second commercial breaks; nor in groups of five eight-hour workdays separated by weekends. The real world marches at you head-on, in jerky bursts of color and boredom and trauma, reminding you that you are alive and small and not in control of anything at all.

My invite-someone-to-America idea had shaped and reshaped itself many times since that morning in Afghanistan. My present plan: When this trip was over I would surprise one of the people I had met along the way, someone who had never been out of his (or possibly her) native country, with an invitation to visit and travel around the United States with me for one month—my treat.

I was uncertain as to just how I would decide whom to invite. Maybe I would meet someone so compelling—so kind, eccentric, or just so much fun—that the choice would be obvious. But if that didn’t happen, I would simply, when I got home, drop everyone’s name into a hat and draw one out.

As I walked through the Ermita district toward Manila’s focal point, Rizal Park, arms shot up from apparently lifeless bundles, palms outstretched. I gave a peso to a man with no legs, and thought: In San Francisco a few cents is an insult.

A young woman, wearing a short skirt and swinging a tiny black purse, caught my eye and slid her tongue across her lips. Even at this hour women in high heels, black net stockings, and frilly red teddies lounged in front of twenty-four-hour bars, and stretched their smooth, peanut butter-colored limbs. Winking at me they cooed, “Hi Joe,” while young men leapt up to swing open the barroom doors. “Very nice, Joe. Very nice.” Through the front door of one darkened place I saw a searchlight slicing through banks of cigarette smoke to highlight a tiny woman in a white Day-Glo bikini, prancing on a bar top.

In ten minutes I reached Rizal Park, a wide swath of green fronting on Manila Bay. On December 30, 1896, Dr. Jose Rizal—a poet, a genius who spoke more than thirty languages, and the spiritual leader of the Filipino struggle against the Spanish—was executed in the park that now bears his name. Photographs show Rizal standing with his back to the poised firing squad, and a formally dressed mob of thousands—Spaniards and Filipinos alike—crowding around to watch. Today the execution ground is a sprawling green lawn, punctuated by flowerbeds and fountains and statues, open-air amphitheaters, and a roller rink. A sea wall, a promenade, and a row of palms lined the water’s edge, and here, hunkered down on benches or spread out on the lawn, hundreds of Filipinos had gathered to watch the mid-morning sun heat up the bay.

I bought a Manila Bulletin from a small boy and found a shaded, empty bench. I had barely opened it when four men—each with a camera, a Rizal Park baseball hat, and a badge: official rizal park photographer—lined up in front of my bench.

“Pit-chur? Next to fountain. Only fifty pesos. Very cheap.”

They stayed, pleading—“O.K., O.K. For you, forty pesos”—until I showed them my own small camera, and then they chased en masse after a French-speaking couple who had strolled by.

A front-page article described the uproar over Webster’s latest dictionary having used the phrase “domestic worker” to define the word “Filipina.” Filipinas and Filipinos everywhere were enraged and insulted. The mayor of Ermita had banned the book’s sale. The dictionary people were holding firm.

Suddenly a small open hand imposed itself between my eyes and the newspaper. A girl—barefoot, with dirt-stained cheeks, no older than six—stood in front of me, a baby boy cradled in her arms.

“No mama,” she croaked. “No papa.”

I asked what had happened to them.

“No mama,” she croaked. “No papa.” The baby gaped at me with stunned brown eyes.

Was this her brother?

“No mama. No papa.”

Recenzii

“Newsham brings back treasures that every wanderer might envy. His journey, at heart, is into humanity.”

–PICO IYER

“TAKE ME WITH YOU IS NO LESS THAN A PAGE-TURNER OF A TRAVEL MEMOIR.”

–MSNBC.com

“What gives this offbeat travelogue its interest is . . . the spirit of innocent generosity that inspires it, and that generally infuses Newsham’s experiences of people and places.”

–The Boston Globe

“UNFAILINGLY ARRESTING AND PROVOCATIVE.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

–PICO IYER

“TAKE ME WITH YOU IS NO LESS THAN A PAGE-TURNER OF A TRAVEL MEMOIR.”

–MSNBC.com

“What gives this offbeat travelogue its interest is . . . the spirit of innocent generosity that inspires it, and that generally infuses Newsham’s experiences of people and places.”

–The Boston Globe

“UNFAILINGLY ARRESTING AND PROVOCATIVE.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

Notă biografică

Brad Newsham